9,59 €

Mehr erfahren.

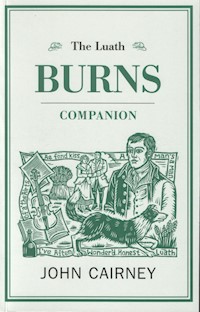

- Herausgeber: Luath Press

- Kategorie: Poesie und Drama

- Sprache: Englisch

This is not another complete works collection but a personal selection of sixty favourite poems, songs and other works, chosen by the Man Who Played Burns , as well as an introduction that explores Burns' life and influences, his triumphs and tragedies. The Luath Burns Companion is a unique introduction to the works of ona of Scotland's best loved poets by a man with an obvious love and depth of understanding for Burns and his work. This selection reveals the drama, passion, pathos and humour that make Burns's work what it is. He was always a forward thinking man and remains a writer for the future.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2013

Ähnliche

JOHN CAIRNEY, ‘The Man Who Played Robert Burns’, is an actor, writer, lecturer and football fan.

After National Service 1948–50 Cairney enrolled at the Glasgow College of Drama and the University of Glasgow simultaneously,graduating in drama in 1953. In 1989 he gained an MLitt from Glasgow University for a History of Solo Theatre and in 1994 a PhD from Victoria University, Wellington for his study of R. L. Stevenson and Theatre.

Cairney’s professional association with Burns began in 1965 with the one man show,There was a Manby Tom Wright. In 1968 he wrote and starred in a six-part serial of the Burns story for Scottish Television,Burns. From 1975–79 his company Shanter Productions organised a Burns festival in Ayr. From 1974–81 he toured the world with his solo version ofThe Robert Burns Storyand from 1981–85 he toured with his wife, New Zealand actress Alannah OSullivan, inThe Burns Experience. In 1986 Shanter Productions presented the first full-length modern Burns musicalThere Was A Lad. In 1996 in commemoration of the Burns International Year a video,Robert Burns: An Immortal Memory, was issued, written and narrated by Cairney.

Prior to and interspersed between these performances he played a multitude of other characters on stage, radio, television and film. His films includeJason and the Argonauts, VictimandA Night to Remember. His theatre work includesCyrano de Bergeracat Newcastle; C. S. Lewis inShadowlandsat the Court Theatre, Christchurch, as well asMurder in the CathedralandMacbethat the Edinburgh Festival. On television he played the lead inThis Man Craig, as well as appearing in many other popular series.

After a number of years in Auckland, New Zealand, Cairney now lives in Glasgow with his wife, actress and scriptwriter Alannah O’Sullivan. Cairney is still very much in demand as a lecturer, writer and consultant on all aspects of Burns.

By the same author:

A Moment White, 1986 (Outram Press)

The Man Who Played Robert Burns, 1987 (Mainstream)

East End to West End, 1988 (Mainstream)

Worlds Apart, 1991 (Mainstream)

A Year Out in New Zealand, 1993 (Tandem Press)

A Scottish Football Hall of Fame, 1998 (Mainstream)

On the Trail of Robert Burns, 2000 (Luath Press)

Immortal Memories,2002 (Luath Press)

The Quest for Charles Rennie Mackintosh,2004 (Luath Press)

The Quest for Robert Louis Stevenson,2004 (Luath Press)

Glasgow by the way, but,2006 (Luath Press)

Greasepaint Monkey, 2010 (Luath Press)

The Luath Burns Companion

JOHN CAIRNEY

LuathPress Limited

EDINBURGH

www.luath.co.uk

First published 2001

Second edition 2008

Reprinted 2008, 2009

This edition 2011 - eBook 2013

ISBN (print): 978-1-906817-85-5

ISBN (eBook): 978-1-909912-16-8

The author’s right to be identified as author of this book under theCopyright,Designs andPatentsActs 1988 has been asserted.

© Luath Press Limited

To Mike Paterson, who drove me to Burns again in 1996

‘That I, for poor old Scotland’s sake,

some usefu’ plan, or book could make...’

Contents

A Letter from the Editor

Burns Facts

Introduction

PART ONE: THE POET

The Poet and the Poems

Poems

The Death and Dying Words of Poor Mailie

A Poet’s Welcome to his Love-begotten Daughter

Holy Willie’s Prayer

Death and Doctor Hornbook

Halloween

To a Mouse

The Jolly Beggars

The Cotter’s Saturday Night

The Auld Farmer’s New-Year’s Morning Salutation to his Auld Mare Maggie

The Twa Dogs

Address to the Unco Guid

To a Mountain Daisy

To a Louse

The Holy Fair

Address to a Haggis

On Meeting with Lord Daer

On Seeing a Wounded Hare

To Collector Mitchell

On the Late Captain Grose’s peregrinations through Scotland

Tam o Shanter

PART TWO: THE RHYMER

A Rhyme for all Reasons

Epistles and Addresses

Epistle to John Rankine

Epistle to Davie

Second Epistle to Davie

Epistle to J. Lapraik

Second Epistle to J. Lapraik

Epistle to William Simpson

Epistle to John Goldie

Third Epistle to J. Lapraik

Epistle to Rev John McMath

Epistle to James Smith

Epistle to Major Logan

Epistle to A Young Friend

Epistle to Hugh Parker

Epistle to James Tennant of Glenconnor

Epistle to Robert Graham Esq of Fintry

Epistle to Dr Blacklock

Epistle to Maxwell of Terraughty

The Rights of Women

Epigrams and Epithets

Elegies and Epitaphs

PART THREE: THE SONGWRITER

The Fiddler and the Folk Singer

Songs

Mary Morison

The Rigs o Barley

Green Grow the Rashes-O

A Rosebud by my Early Walk

Sweet Afton

Of A’ the Airts the Wind Can Blaw

John Anderson, my Jo

Ca the Yowes to the Knowes

To Mary in Heaven

Comin Thro the Rye

The Banks o Doon

Bonie Wee Thing

Ae Fond Kiss

The Deil’s Awa wi th’ Exciseman

Whistle and I’ll Come to Ye, My Lad

Scots Wha Hae

My Love is Like a Red, Red Rose

A Man’s A Man

O, Wert Thou in the Cauld Blast

Auld Lang Syne

The Heron Memoir

Postscript

APPENDIX I Myths and Misconceptions

APPENDIX II Some Burns Contemporaries

APPENDIX III The Posthumous Burns

APPENDIX IV Chronology of Complete Works

APPENDIX V Editions of Works

APPENDIX VI Miscellaneous Editions and Manuscript Collections

APPENDIX VII Biographies and Burnsiana

A Letter from the editor

Dear Reader,

Thank you for taking up this book. As you can see, it is not another Complete Works. These are available all over the place, and have been for more than 200 years. Burns has never been out of print since 1786, and I can’t see what can be gained by adding yet another edition. This, however, is a Selected Works, and the selection is mine, which means it is a personal view of the poet and his life and work. This means that this book might best be regarded as a companion to Burns, an eclectic choice compiled by one who has virtually lived with the man in the study, on stage, and before the cameras for nearly 40 years.

You may not not agree with my choice, of course, but it’s been made on the grounds of affectionate companionship, as he has been my professional companion for more than half of my acting and writing career. After all that time with the poet, I have come to know him, or at least my view of him. I have also come to respect, admire and like him as a man. Even his many faults I recognise as my own, and most every other man’s, always bearing in mind his own comment,‘how many have been proof against the weaknesses of mankind, merely because they were never in the way of them?’

What is more important, however, is that I have never tired of him. There is always something about the man, or his work, or his friends that takes me by surprise. A trick of rhyme, a turn of phrase, a striking thought, an unexpected attitude, you never know what is going to catch your eye as you turn the pages. He is alway interesting, even when he is not being very nice. How many people can you say that of after a 40-year relationship? A lot has been written about Burns since Robert Heron’sMemoirof 1797, but I make no apology for adding to the pile. I think you can never get too much of a good thing and there are plenty of good things in Burns. This volume is an attempt to condense most of them.

The Contents are in four sections – an Introductory essay on the life of the man who was Burns, then his work is divided into three categories – The Poet, The Rhymer and The Songwriter. The selected items in each category are in chronological order except where a particular item is required to illustrate a theme or to introdce a new section. I start with some facts about him that might be useful and end with a complete chronology of his whole output. It is astonishing to see just how much he wrote in a very brief life, and to my knowledge it has not been laid out like this since Duncan McNaught’s article in theBurns Chronicleof 1895. This is the complete canon. Everything is here in this summary, the good, the bad, and the wonderful. To use a modern word, correctly for once, it is awesome, but to put itallin a book would neither serve Burns nor the modern reader. Hence this selection.

To some, Burns was a poet first, and a songwriter second, but there are others who have exactly the opposite view. To me he is the ideal amalgam of both, having the ability to make poetry within a song, and make verse that almost sang. That ability is perhaps the hallmark of his genius. And even if he did write fewer poems as he grew in letters, he made up for that in his song industry both as collector and adaptor. He breathed new life into a song tradition that was thought dead and for that Scotland and music must be forever in his debt, but Robert Burns needs no apologist for his work. It speaks for itself, but he did enjoy his friends and his companions. Having made a lifetime journey with him, figuratively speaking, I feel I can offer this collection as from a friend and companion, in the hope that he will stimulate and delight as many in the new century as he had done in the last two.

I am highly indebted to Dr James A. Mackay for the use of his exemplary Burns scholarship as shown in the bicentenary volume of the Works published by the Burns Federation in 1986 and to W. E. Henley and T. F. Henderson for the same standard of research shown by them in the Centenary Edition of 1896. I must also acknowledge the Rev John G. Hill’s 1961 book on the Love Songs which proved invaluable and I continue to be grateful to my on-going Burns mentors like Dr David Daiches and Dr Maurice Lindsay. However, most of all, I treasure the memory of the many, many nights I have shared Burns with an audience. This is where I really began to understand and appreciate him. I hope this book will help you, the reader, to do likewise.

So here you are then, a very personal view of my Robert Burns. Please share him with me in these pages.

Thank you.

John Cairney(Dr)

Auckland,

New Zealand

P.S.

One of the many sources to which I referred in writing this book wasBurns – A Study of his Poems and Songsby Thomas Crawford (Oliver and Boyd Ltd, Edinburgh, 1960) which superseded John McVie’s excellentSome Poems, Songs and Epistlesof some years before. However, what I had not noticed before was that Dr Crawford’s book was also written in Auckland, New Zealand in 1959. I just hope he enjoyed the process as much as I did, in the South Pacific sun 12,000 miles away from our mutual motherland, the Land o Burns.

Burns Facts

Born Alloway, Ayrshire, Scotland, 25 January 1759.

Worked as farm labourer for father in Ayrshire.

Founded Bachelors Club at Tarbolton, 11 November 1780.

First Commonplace Book, April 1783.

Elected Depute-Master, St James Lodge, Kilwinning, 27 July 1784.

First child born to Elizabeth Paton, 22 May 1785. A daughter.

PublishedPoems,Chiefly in the Scottish Dialect, at Kilmarnock, 31 July 1786 by subscription.

Twins born to Jean Armour, 3 September 1786. Jean (d.1787) and Robert (d.1857).

Second Commonplace Book, April 1787.

Son born to May Cameron, Edinburgh, 26 May 1787.

William Creech publishes first Edinburgh Edition, 17 April 1787.

Thomas Cadell publishes first London Edition, 1787.

Works with James Johnson onThe Scots Musical Museum1787/88

Sets up Jean Armour in Mauchline house, 23 February 1788.

Twins born to Jean Armour, 3 March 1788. Both stillborn.

Enters marriage arrangement with Jean Armour, May 1788.

Buys farm at Ellisland, near Dumfries, 11 June 1788.

Commissioned in the Customs and Excise, 14 July 1788.

A son born to Jenny Clow, Edinburgh, November 1788.

First Dublin Edition ofPoems, 1789.

Francis Wallace Burns (d.1803) born to Jean, 18 August 1789.

WritesTam o Shanter, December 1790.

Daughter born to Anna Park, Dumfries, 31 March 1791.

William Glencairn Burns (d.1872) born to Jean, 9 April 1791.

Moves to the Wee Vennel in Dumfries, 11 November 1791.

WritesAe Fond Kissfor Nancy McLehose, 27 December 1791.

Promoted to Dumfries Port Division, February 1792.

Elected to the Royal Company of Archers, 10 April 1792.

Begins work on Thomson’sSelect Collection of Scottish Airs, 1792.

Elizabeth Riddel Burns (d.1795) born to Jean, 21 November 1792.

Second Edinburgh Edition ofPoemspublished 18 February 1793.

Moves to Millbrae Vennnel, Dumfries, 19 May 1793.

James Glencairn Burns (d.1865) born to Jean, 12 August 1794.

Joins Dumfries Volunteer Militia, 31 January 1795.

WritesA Man’s A Man, December 1795.

Dies 21 July 1796 just after five o’clock in the morning, aged 37.

Maxwell Burns (d.1799) born to Jean, 25 July 1796.

Funeral procession of Burns from theMid-Steeple to St Michael’s Kirkyard, Dumfries, 25 July 1796.

Introduction

‘There was a lad was born in Kyle...

Twas a blast o Janwar win’ blew hansel in on Robin...’

It may be said that Robert Burns was born in a thunderstorm and lived his brief life by flashes of lightning. The first flash revealed the poor, clay-walled, thatched cottage where he was born on the evening of 25 January 1759, and the last dwindling light showed through the rain of that day, the respectable stone-built Dumfries, house where he died on 21 July 1796. The thirty-seven and a half, tempest-filled years between were either bright with joyful creation, both physical and artistic, or dark with poverty, sickness or melancholy, all of which were to haunt him throughout his life. Things were always to be black or white with Robert Burns with little middle ground between. He was either very high up or very low down, and regrettably, he was down rather more than he was up. In addition, he was dogged throughout by money worries, more imagined than real, but he had known the bite of poverty from his earliest years and he was never to forget it. Even at his end, the last thing he wrote was a begging letter.

Yet he had his glorious hours in the sun, when poems and songs fell from him with a supreme ease and people flocked to hear him speak his rhymes, or just to have a look at him. Robert Burns was really two different people. His first person was the one who lived in a remote corner of 18th century Ayrshire until the publication of his only book,Poems, Chiefly in the Scottish Dialect. The book was published by subscription at Kilmarnock on 31 July 1786, and sold out in a matter of weeks. This phenomenon bred the other Burns who lived in Edinburgh and Dumfries, and to a large extent, on his meteor fame, for the final decade of his life. The poor ploughboy-scholar who grew up on his father’s succession of failed farms seems little related to the literary dandy who made a royal progress throughout Scotland after the publication of the Edinburgh Edition in 1787, but they were one and the same man.

It was only for a handful of years, but this latter Robert Burns was arguably the most famous man in Scotland in his day, known to masters and servants across the land. He was as much at home in my lord’s castle as he was in the cotter’s but ’n’ ben, for man and boy, he mirrored them exactly. The poet-artist in him was on a par with any peer, and the boy-Burns was of the same serf-soil as the most menial of farm labourers. This dichotomy is central to an understanding of the man he became and perhaps is at the core of his complexity as an individual.

It has always to be borne in mind how very young he was. He was never to grow old; he died before he was middle-aged, and his best work was done before he was 25. Given the quality of most of his poetry, this is hard to believe. What is more, it was largely written from 1785 to 1786, when masterpieces flew from his goosefeather like chaff from the thresher. In this golden year, and in the few months before and after, came all the great poetical works as well as many of the immortal songs, not to mention the verse epistles, epigrams, epitaphs and letters, and all in a copperplate hand that was his trade mark.

Everything seemed to come easily to his hand and with a fluency remarkable in one so young. At the very least it was proof of an astonishing industry and application. When one considers the fragmentary nature of his conventional education, it is remarkable, not that Burns wrote so well, but that he wrote at all. The credit for this undoubtedly belongs to his father.

My father was a farmer upon the Carrick border

And carefully he bred me in decency and order.

No real consideration of Robert Burns can be made, as Robert Louis Stevenson pointed out, without reference to the extraordinary man that was his father. William Burnes was born in the Mearns in the North East of Scotland, and had come down to the South West not long after after the troubles of the ’45 Rebellion, to find a farm of his own and found a family. Burnes had his own claim to be unique. He was a Scottish peasant with a mind. Totally disregarding his given station in life, he made himself as well read as he was able, and in so doing, developed an impregnable sense of individual certitude founded on the Presbyterian Bible and an unswerving trust in a just God. How this upright, virtually Puritan man – by then a market gardener in Ayr – came to marry Agnes Brown of Maybole is the first mystery of the many that make up the Robert Burns story.

Nessie Brown was a short, vivacious, red-haired, black-eyed bundle of energy, full of songs and stories. She was much sought after in her own area, but turned down other offers to take the sombre Burnes as her husband in 1757. This apparently ill-matched couple produced six children in all, but they are only remembered today by reason of Robert, their first-born. He is so clearly a pattern of both, each imprinted on him in almost equal degree. His character is the sythesis of two opposites, and this was the basis of his seemingly contradictory nature. This was inevitable given that the parents were so different from each other. Where William was given to discourse, Nessie was given to song; where he was grave, she was merry; where she was witty, he was wise. In no area of personality did they seem to overlap, but they gave to their son the best of each of them.

Even though he got his dark, gypsy good looks from his mother, the maternal gift was almost entirely emotional. Thanks to her, his feelings went deep but they as often dragged him down as lifted him up. However his mother’s contribution was also artistic. From her came his sound musical instincts and a generous sensual appetite. Fortunately, in his case, this was tempered by an easy charm which was, by all accounts, irresistible – especially to women. His gregarious and convivial side, his wit and love of the social hour among other young fellows, all drew from his mother’s influence. Strange then that he never wrote one word about her and only in the last days of his life did he send his regards to her. All through the high days of his Edinburgh fame she lived with her second son, Gilbert, in East Lothian but there is no record of Robert’s ever visiting her.

This reserve with his mother could be at the root of Burns’s ambivalent attitude to women generally. They were either socially beyond his reach (as were many of the heroines in his songs) or under his feet. He was never able to meet with women as fellow-mortals. They were always to be different. There was an element of boyishness in his attitude to the other sex, and again this may have its roots in his attitude to his mother. He liked women as much as he loved them and he understood them. This was shown by how unerringly he was able to write in the voice of a woman in his songs.John Anderson, my Jo, for instance, is surely the finest-ever anthem to married love, and a wonderful, indirect compliment to his parents.

From his father came another kind of passion – a passion for words. To him, Robert owed his mind. This duality, the struggle between the man of feeling and the man of thought is at the base of his personality. In the future poet, the body was always at war with the soul. The opposite elements in his genes, contrasting and paradoxical, gave to his nature a two-sidedness that confused and complicated his attitudes and actions. The rigid philosophical spine connected to a considerable mind but it was always at odds with the generous and demanding animal. His character was a constant see-saw between these two extremes and it was this that gave him a life-long sense of guilt. We cannot begin to understand Burns unless we understand this.

The paternal legacy was compounded of integrity, compassion and a sturdy independence of mind. The boy is father to the man, but the father in this case was the boy’s first companion, first teacher and, in every sense, his mentor. The father also passed on to his son the same love of the printed and spoken word he so enjoyed himself. He gave the boy all he would need to make his way in the world, but that included a very Scottish diffidence about self-seeking which, in this case, was hardly what an aspiring writer needed. Nevertheless, the moral ethic implanted gave Burns a spine of inherent decency which runs through all his work and informs the best of it. His sturdy independence, manly gaiety and love of the word, sung, spoken or on the page, are certainly the synthesis of his unique parentage and the manifestation of a pedigree that never suggested the emergence of a literary figure of any status, still less a genius.

Robert Burns may have had the best of each of his parents, but their very opposites occasionally brought out the worst in him. Nevertheless this imbalance was at the root of his genius. None of us can choose our parents. Similarly none of us can be a genius merely for the asking, but the fact remains that William Burnes and Nessie Brown produced the man we know as Robert Burns. By their very differences, as we have seen, they made him the two persons in one as already proposed above. This double identity appears to be a particlarly Scottish phenomenon. ‘Two-facedness’ or the duality of character within one nature is something which has concerned many Scottish writers, such as Stevenson and Hogg, and Burns himself in his work. This is not to say that hypocrisy is a hallmark of the Scottish character, but it does lend an insight to the two sides of Burns that were often in opposing action in his lifetime. It was this which caused him to seem at odds with himself and his environment. The man of thought versus the man of feeling, the cerebral scholar against the sensual role-player. The story of his life is the history of this on-going battle between his body and his soul. It was this vital aspect of his psyche made him the poet he became.

Nothing in his pedigree prepared him for poetry nor for the exceptional talent he was to have for it. The ‘weary slave’ who survived the grim boyhood, was an unlikely candidate for any kind of literary status, but, father-driven, with a book in one hand and a flail in the other, he won his way through a whole library of Augustan reading to become as well read as his temporary tutor, John Murdoch, and as fiercely book-based as his parent. Burns, in fact, was an auto-didact who gave himself, by almost constant reading, what amounted to an entirely English education. Apart from Blind Harry’sHistory of William Wallace, he read very little of his native Scots as a boy, mainly because there was so little, if any, printed work in his own dialect available to him. His early reading was grounded in English authors but what better training in written language was there, and when this was added to the spoken absorption of his Scottish mother-tongue, one can see that a formidable wordsmith was in the making.

From the very beginning, the boy had an instinct to better himself. He knew somehow he wasn’t destined to be broken on the land like his father before him. Something told him that he was different, and he prepared for fame with the sure knowledge that he would one day attain it, despite‘the unceasing moil of a galley slave’that he knew growing up. Genius is nothing if not sure of itself. He took to rhyming as a way of life because life itself had so little to offer him. It was not only a respite, it was an escape. He was a peasant born to a peasant and he should have known his place, but both father and son knew there was something more and words were the key to it. Burns ate them up as greedily as he supped at the miserable crowdie that sustained them all. He was already in training for his future. The good father was aware of this.‘Who lives, will know that boy,’he said to his wife. And Gilbert Burns was later to write of his older brother at this time,‘He was always panting after distinction.’

In the meantime, he had first to survive. As long as there was light they would labour, and when darkness fell, they would fall in at the door, too tired to eat, too hungry to be refreshed by slumber. Robert Burns lived two lives as a boy. One, as a struggling farmer’s son, was to break his body and help him to an early grave. The other, as an apprentice writer and reader, was to form his poetical skills and make him immortal. But for now, everything was directed to the daily, dreary drudgery of the kind of farming he and his family knew. Like them, he had one, simple, clear goal – to stay alive, and wait for the second flash of lightning. While he waited, he began to scribble his thoughts into a Commonplace Book. Commonplace thoughts perhaps but he had to start somewhere.

Observations, Songs, Scraps of Poetry etc, by Robert Burnes, a man who has little art in making money, still less of keeping it, a man, however, of some sense, a great deal of honesty and unbounded goodwill to every creature...

The next lightning flash did not come in the writing, as it happened, or the reading, but in the winsome form of a young girl in the harvest field. The custom then was to partner the labourers in the field, man with woman, boy with girl, as the community joined to bring in the harvest. When he was 15, his partner was a young girl just one summer less than he, who, it appeared, had a song written about her by a laird’s son. Young Burnes thought he could do as well as any laird’s son, so for the 14-year old Nellie Kilpatrick, beside him in the field, he wrote his first song:

O, once I loved a bonie lass, ay, and I love her still,

And while that virtue warms my heart, I’ll love my handsome Nell...

The words were silly, by his own admission, but he was on his way. From this time on, Robert Burns was to be in a permanent state of being in love. It was vital for his muse that he was in love with somebody. As he had said,‘I never thought to turn poet till I got heartily in love’, but what he really meant was not love but sex. Fresh, disturbing, exciting, young sex but that didn’t matter. The important thing was that lightning had struck again, and by it, poesy was opened up to him via the young female.

There’s nought but care on ev’ry han’,

In ev’ry hour that passes-O.

What signifies the life o man,

An twere na for the lassies-O!

He had grown into a handsome youth, and his reading had given him an extensive vocabulary, unusual to say the least, for an Ayrshire tenant-farmer’s son. And he was not afraid to use it. It was no accident that he founded the Tarbolton Bachelors Club which was open to all‘professed admirers of the female sex’. He was assiduously rehearsing the future role he was to play, and with his saffron plaid, tied hair and buckled shoes, he was certainly dressed for the part. He cut a dashing figure in the parish and was loud in his admiration for most of the local girls, although truth was he could only talk a good seduction. He was as innocent as they all were, but there was no doubt he was caught by a few of them, especially one whom he chose to call Mary Morison.

Tho this was fair, and that was braw,

And yon the toast o a’ the town,

I sigh’d and said, ‘Amang them a’

Ye are na Mary Morison.’

The limpid directness of that last line contains the secret of high art. By being honest to himself and his situation in the poem, he had stumbled on poetry. This boy was no mean rhyming hack; he had found his voice early and he had found it through women, and he was to be true to both till life did them part. This thrilling economy with a line was to make him near the end of his life one of the greatest songwriters of all time, but first he had to write a great deal of verse.

Ironically, he couldn’t begin properly with his life, or his life’s work, until he was free of his father, the man who had done so much to make him the artist he would become. William Burnes died at Lochlea Farm on 13 February, 1784, aged 63, and worn out by hard toil and‘the snash of cruel factors’. Legal action he had taken against a greedy landlord had gone all the way to the High Court of Session in Edinburgh which found in William’s favour, but the case had bankrupted the family and the victory came to the father on his death-bed. His last words were for his first son,‘It’s only you I fret for’– then he was‘carried off to where the wicked cease from troubling and the weary are at rest.’

Robert and Gilbert quickly moved the family over the hill to Mossgiel, another farm near Mauchline, to avoid further creditors, and start all over again on their own. This time, Burns left the running of the farm to his brother and took up his pen as if it were a sword. He would cut himself free from farming and he would do it in verse. He was 25 years old and raring to go. He had nothing to lose but his head. Rab Mossgiel was born and ready to take his place as the Ayrshire Bard.

Beware a tongue that’s sweetly hung,

A heart that warmly seems to feel,

That feeling heart but acts a part,

Tis rakish art in Rab Mossgiel!

If the death of his father released his muse to soar, the same loss of restraint allowed for other explorations in another direction. As a further precaution against litigation both brothers changed their names officially from Burnes to Burns. Robert was free to be himself at last. Almost the first thing he did was to enjoy the freedom of a young serving girl in the house, Bess Paton, and the natural result in the following year was his first child – a ‘misbegotten child’ or bastard wean. Being Burns, he could do no less than trumpet his pride to the world in the first poem in literature to celebrate the tangible result of love. A child was a child and this was his child. His first.

Welcome my bonie, sweet, wee dochter!

Tho ye come here a wee unsought for,

And tho your comin I hae fought for,

Baith kirk and queir;

Yet, by my faith, ye’re no unwrought for –

That I shall swear!

Needless to say, this paean to parenthood was not among his published works in his lifetime. Like so many of his greater works, it was thought to be indelicate and unfit for gentle consumption, but this particular poem has long outlived its first prissy detractors and exists today for what it was, and still is, the spontaneous outpouring of a young father’s feelings on seeing his child for the first time...

What tho they ca’ me fornicator,

And tease my name wi kintra clatter,

The mair they talk I’m kenn’d the better,

E’en let them clash;

An auld wife’s tongue’s a feckless matter

To gie ane fash.

Bess Paton left the district soon afterwards leaving Burns holding the baby. He promptly gave it up to his mother and sisters, to bring up as one of their own. The which they did, until she was married herself. Burns hardly mentioned the matter again.

Auld Nature swears, the lovely dears

Her noblest work she classes, O:

Her prentice han’ she try’d on man,

An then she made the lasses, O.

His mother had wanted him to marry Bess but he couldn’t. He didn’t love her. Bess had understood, but his mother hadn’t. She never spoke to her son again, leaving him to his own devices. Burns, however, having been given a taste of women, wanted more. The serious-minded Tarbolton bachelor gave way to the young Mauchline bull, who now proceeded to run wild among the startled maidens of the parish, but in reality, making more noise than mischief.

It was upon a Lammas night when corn rigs are bonie

Beneath the moon’s unclouded light I hied awa to Annie.

The time flew by wi tentless heed, till tween the late and early

Wi sma’ persuasion she agreed to see me through the barley.

He became known in the town as a maker of rhymes – and for much else. Freed from his father at last, he could now do more or less as he pleased. And it pleased him most to make love and verses, and generally, in that order.

Miss Miller is fine,

Miss Markland divine,

Miss Smith, she has wit

And Miss Betty is braw,

There’s beauty and fortune

To get with Miss Morton,

But Armour’s the jewel for me o them a’.

Jean Armour was the first serious love of his life and was to be his last. This particular Mauchhline belle, favourite daughter of the local stone-mason, was to become the wife of Burns, and the mother of their nine children, only three of whom would survive into adulthood. She was the rock on which he would build his family and she stood firm no matter how the winds blew around them. Jean Armour was to remain the constant, the only factor that was to be common to both halves of his life – that is, the Burns before the publication of his poems and the Burns after it. They were to prove two quite different people but they were both the same Burns to Jean.

In 1785, however, they were very young, and Robert was rampant – in every sense. Poems flew from his hand as fast as seed from his body, and both with the same fervour. Almost at once, Jean was in her first pregnancy and Burns was in consternation. Coming hard as it did after the scandal of Bess Paton, it was the beginning of the thunder and lightning that typified the meteorological complexities of his love life. A whirlwind now blew around them from all sides. Burns tried to appease Jean and her father by writing a paper declaring themselves married in the eyes of God, but her father declared that he knew his own daughter better than God did and packed her off to Paisley.

But not before they both had to suffer three Sundays running on the cutty stool before all the congregation and take their reprimand from the Minister. The Kirk ruled in rural Scotland and the Kirk elders ran the parish, ever on the look-out for transgressions, especially‘ye sin of fornication’. William Fisher, one of the elders, was especially assiduous in seeking out those who‘sinned against the flesh’and Robert Burns was a ready target. His retort was to‘puzzle Calvinism with much heat and indiscretion’and write his shattering satire on Fisher –Holy Willie’s Prayer.

O Thou that in the Heavens does dwell

Wha, as it pleases best thysel,

Sends ane to Heaven an ten to Hell,

A’ for they glory,

And no for any guid or ill

They’ve done before Thee.

In the months that followed, deprived of Jean, he took his solace where he found it – at Freemason meetings, drinking sessions and any occasion at all that allowed him to take a girl in his arms. He was on the rebound and it landed him in places like Poosie Nansie’s Tavern where he could enjoy the company of tinkers and trollopes, soldiers and beggars, all the low life of the road, met to sing and dance, but mostly to drink. Burns watched and listened, and as a result, produced TheJolly Beggars, a brazenly bawdy song scena, and his first masterpiece. It was an unkempt hymn to love and liberty and he delighted in it as he delighted in the free spirits of the derelict and down-and-out.

What is title? What is treasure?

What is reputation’s care?

If we lead a life of pleasure

Tis no matter how or where.

Life is all a variorum

We regard not how it goes

Let them cant about decorum

Who have character to lose.

He lived only for the moment and for the making of verses, short and long, verse-letters, epigrams, epitaphs, songs – and scraps of poetry. He made his verses and rhymes the way he made his children – spontaneously and naturally, but he was inching nearer and nearer poetry with every line.

The notion of seeing his words‘in guid, black prent’had been planted just a few years earlier when, during a walk in Leglen Woods near Irvine with Richard Brown, the future sea-captain suggested that the 22-year old Burns’s verses were good enough to print in a newspaper, even a book. Even a book? The young rhymer was caught, even though at first thought, the idea seemed preposterous. Who would buy a book of ploughboy scribbles? Yet the idea persisted, and in 1785 it all came to a head.

1785 wasannus mirabilisand his heart was in everything he did. Everything that was later to make his name was written in and around this one tremendous year. He was driven forward in a white heat of creativity and nothing could stop it – or him. Everything in his life up till that time had prepared him for this moment. All the silent hours of stolen boyhood reading, all the earnest discourse with his pedagogic father, all the songs he had heard at the hearth, the stories round the frugal table, it was all grist to this mill, which now ground out at full tilt the first harvest of all his artistic instinct.

The posturing and bravado of his innocent youth was set aside as he touched on real feeling for the first time, and he couldn’t believe what he found he could do with words. It was an amazing tide and it almost swept him off his feet but he kept his head as his local fame as a bard grew by the hour, and what was, in effect, his life’s work, apart from the late songs, was written in the nine months between July 1785 and April 1876. Nine months.In the time it took to make a child, he created a corpus of poetic work that would prove to be timeless. And he was only 26 years old.

He was at the very height of his physical and mental powers. He could have done anything it seemed. And what he wanted to do, apparently, was emigrate. He had suddenly decided that he would become what he called‘a negro-driver’in Jamaica. Everyone was astonished. And puzzled. But he seemed determined. This far-fetched plan to emigrate had arisen out of a desperation about his affairs at home. He was no further forward with Jean Armour and had now become involved with a Highland nursery-maid, Mary Campbell. He wanted out of farming, he wanted out of Scotland. There was nothing to hold him to either. So he gave up his share of Mossgiel to his brother, Gilbert, and concocted a scheme with his lawyer friend, Gavin Hamilton, to buy a passage to the West Indies for Mary Campbell and himself.

Then Farewell Scotland, I shall never see you more.

But how to raise the money for the voyage? Other friends, like Robert Aiken and John Ballantyne, suggested that he publish some – not all – of his poems in a book and raise the cash through sales. Sell a book of poems?Hispoems? Why not? It was his fate to be a poet, and he knew it. But a whole book? Could he do it? Of course he could. He had no doubt. He reasoned that if even if the book failed,

the roar of the Atlantic would drown out the voice of censure.

This was to be the third lightning flash. The first had found him in a cottage, the second had shown him women and poetry, and now, the third, revealed the prospect of paid authorship. This prospect had been opened up by the Freemasons. His Masonic contacts were now to prove invaluable. Undoubtedly, without the Freemasons in Scotland at that time, there would have been no book, and, therefore, no Robert Burns, at least as we know him today.

Significantly, his own initiation in the Craft came in July 1781, the same year as he was given the idea of printing his own work by Captain Brown. He had been proposed at his local Lodge, St David No 24, Tarbolton, (later to become the St James, Kilwinning), by Gavin Hamilton. Within months he had passed to the Fellowship Degree, and before the end of the year he had been raised to the Degree of Master. By the time he began to think seriously about putting out a book he had been elected Depute Master. In unusually quick time, he was to became a Mark Mason, a Royal Arch Mason and a Knight Templar, a rare level indeed, but then suddenly, in the last year of his life, like Mozart just beforehisdeath, he gave up the Masons, or they gave up on him.

However, at the beginning, there were many reasons why Burns enjoyed being a Freemason. The first was the opportunity it gave him to revel in easy male company. It was a natural step up from the Tarbolton Bachelors’ Debating Society. Secondly, its principles of brotherly love and the betterment of mankind by intellectual development were entirely in accord with his own views. Thirdly, its egalitarian structure, where titles meant little, and‘a man’s a man for a’ that’, were exactly in line with the new sense of freedom being promulgated in the late 18th century by the European Enlightenment, with its return to classical and rational principles. This might have been seen to be subversive and therefore dangerous in Burns’s day, and no doubt that would have appealed to him too.

However, it was the Masons who came to Burns’s aid, and just when he needed them. Gavin Hamilton took Burns to the St John’s Lodge in Kilmarnock, where he persuaded some of the members to open a subscription for the publication of‘Poems, Chiefly in the Scottish Dialect’by Robert Burns. The cost of the paper, estimated at twenty seven pounds, had to be met before any work could be started. John Wilson, the Kilmarnock printer, was also a Mason, so it must be supposed that Burns got a good deal. Even so, it was much more than he or Gavin Hamilton could afford, so help was needed and that came from nine good men of Killie – Will Parker, Tam Samson, Robert Muir, John Goldie, Gavin Turnbull and Doctors Moore, Hamilton and Paterson – who pledged between them 350 of the 612 volumes projected. With this assurance, the printing of the subscription sheets was put in hand and Burns had taken the first step to becoming a printed poet. For the first time in Lodge records, he was referred to as‘Poet Burns’, a legend that was to apply to him for the rest of his life.

It might have been expected, then, that he was a happy man, but happy he certainly was not, and the reason was Jean Armour, or rather her father. Seemingly, when he was first informed that Jean, his favourite daughter, was pregnant, he fainted. On being revived with the best Ne’erday brandy, and being told that Burns was the father, he fainted clean away again. Now Jean returned from Paisley with twins, a boy and a girl, and proudly admitted that Burns was the father. This time, Armour slapped a warrant on Burns for his arrest by the Sheriff’s officers for failure to provide Jean with maintenance for herself and any child – or children. The Kirk also fined him for fornication. In addition, Mary Campbell had gone to the port of Greenock to await him and had died there.‘Of a malignant fever,’it was said. The Campbell family were supposed to be after his blood. Things did not look good for the putative poet. He went into hiding at one of his aunt’s farms until he could escape to Jamaica, but then, on 31 July 1786, the book came out – and suddenly everything changed.

Poems, Chiefly in the Scottish Dialectby Robert Burns. One volume, octavo, price stitched, three shillings. It is worth more than three thousand pounds today. The Kilmarnock Edition. One little book of verse. But it changed his life forever. Every copy printed was sold within a week. Almost every household in Ayrshire had one except the Burns family at Mossgiel. They had never thought to subscribe. Not that it mattered, the first son of the house was now a poet in print, and with a book in his hands to prove it. How he must have wished his father could have seen it. Not only would he have been proud, he would have felt justified. Burns was now called for on all sides, and in the the taverns was proclaimed the Ayrshire Bard. Suddenly, he was famous. Armour withdrew his warrant and the Campbells retreated to Campbeltown, so that Poet Burns could have his local hour.

Every line he had ever written was a determined step to win his way out of farming and a life of drudgery. From being a parochial rhymer he had made a huge step into print. National fame now beckoned as a Scottish poet. Everything had to be re-thought – emigration, marriage, career – but the first priority was, without doubt, a second edition. However, Mr Wilson could not be persuaded that Ayrshire wanted another book of poetry so soon, and if it did, he would have to be paid in full up front. Burns packed his trunk again for the Indies. It was already on its way to Greenock by the carter when he got a letter from a Dr Blacklock suggesting that he try for a second edition in Edinburgh. Edinburgh? Why not? Burns was charged by this time and nothing was going to stop him now. As far as he was concerned, Edinburgh was just as foreign and far away as Jamaica. It was as good an escape as any. Let another ship sail without him, he hired a horse and set out for the capital.

Then out into the world, my course I did determine,

Tho to be rich was not my wish, yet to be great was charming...

He was completely overawed by the big city and didn’t move out of his lodging for two days. When he did, it was to attend a meeting of the Canongate Lodge, Kilwinning. Here, Burns was hailed as the Ayrshire Bard by influential fellow-countymen resident in the capital and introduced by them to his new patron, the Earl of Glencairn. The good lord arranged a quick visit to a tailor for his newprotegeso that Burns might appear in the familiar buff waistcoat and blue top-coat which was to become his bardic uniform. And so, at the St Andrew’s Lodge, in a great company of gentlemen and distinguished visitors from abroad, Burns was proclaimed‘Bard of All Scotland’. What a situation for a poor country lad. Fortunately, he made an effective reply and sat down to great applause.

It must be understod at this point just how far Burns had come in his 27 years. A man born in a poor station in a remote corner of an even poorer country which at the time was trying to adjust to becoming North Britain after being shamefully sold as a nation only eighty years before. An old Scotland was being lost before the new Scotland could be realised and now a young poet had arisen and was being proclaimed Scotland’s Bard. It was heady stuff. It was as if he were meant to arise just at this time to remind the ordinary people of Scotland, who read him first, who they were and where they had come from before they were lost in the furnaces and manufactories of the new industrial age that were already growing up around them.

Janus-like, Burns pointed both ways, backwards to the old Scotland of the Makars and forward to the Enlightenment and the begininng of Modernity. He stood at the watershed of a new tide of change that was sweeping all of Britain. Revolution may have been in the air but prejudice was still thick on the ground, and Burns soon found himself uncomfortably with a foot in each camp. All his new patrons, and most of his new acquaintances were of the gentry and the landed class, while his old friends were of the land. That is, they were peasant-bound to it and tied for life, unless they could break away to schoolmastering or the law. Burns escaped to letters. His book also marked a watershed in his own life, for after it, he was never to be the same man again.

He began to feel he had been born to the wrong parents, as much as he loved and respected them both. Lines of social demarcation were clear in Scotland in his lifetime. The Divine Right, which had sustained a whole line of Stuart kings, had filtered down the class ladder only gradually and those on the higher rungs were convinced that God had made them from a finer kind of dust, and were sure that the quality lessened as it descended through the pre-ordained pecking order to what they called the lower orders. The trouble was that those at the base, at actual ground level, believed this too, and felt that theirs was a coarser grain than the gentry, but no one had told Burns this. His father had seen to it that he knew his place, and that it certainly was not with those who fatalistically accepted their lot as part of God’s plan for the human race.

In his time, too, there was no aristocracy of the arts. There was no way in which his talents would have carried him far for their own sake. His gifts of social ease and his conversational skills, not to mention his writing, would have stood him in good stead in today’s arts market place, but in 1787, he was still, as far as Edinburgh society was concerned (and that meant, in effect, Scottish society) firmly fettered to the farmyard. One might make one’s way out of one’s station, but only so far it would seem, and then the barrier came down – even to genius. One had to be born to greatness, it would appear, and certainly to privilege. It was small wonder that Burns bristled at his first contact with this unreal world inhabited by the few. And yet, had he known, he could have entered Edinburgh with palms under his feet. Be that as it may, the Robert Burns Story, as the world knows it, could now begin.

My Lord Glencairn proved an efficient patron and thanks to his efforts, and the support of the gentlemen of the Caledonian Hunt, a second edition of the Poems was put in hand almost at once with Mr Creech, the bookseller in the High Street. He had struck lightning again. Thanks to Creech, he also met with the formidable William Smellie, printer and founder-editor of theEncyclopaedia Britannica. Smellie was also founder-President of the Crochallan Fencibles, a company of wits and rakes who met regularly in Dawny Douglas’s tavern in the Anchor Close for sessions of jocular talk and serious drinking. Burns soon became one of its most popular members and made new friends like Woods, the actor, Clarke, the musician, and Naysmith, the painter. He came into his own in such convivial company and he revelled in their companionship.

He also enjoyed that other kind of companionship offered by May Cameron, a serving-girl at Mrs Carfrae’s, where he lodged. But if he played hard by night, he worked as hard all day. He had a book to get out and most of his waking hours were spent on a high stool in Smellie’s print shop correcting proofs. When these were completed, and the second book came out to the same rapturous reception, invitations poured into Baxter’s Close. Every door was open to him. Every table had a place set. Every hand was offered. He refused no one. By the new lightning light, he saw that he was indeed famous. This wasn’t Ayrshire, this was the world. And a whole new world it was, this candle-lit world of Edinburgh celebrity and he relished it. No one enjoyed being famous more. Who wouldn’t? He was 27 years of age, in good health for once, and for the first time in his life, he had leisure and the money to enjoy it.

He resolved to take a holiday tour through his native land. Besides, he had new contacts to make, and book monies to collecten route. It was a triumphal progress. Crowds flocked to gaze on the famous Bard as he passed through village and town on the way. With various friends at various stages, he made a detour around the Borders, being given honours and freedoms at every stopping place. His book had gone before him. Eventually, he pointed his horse towards Mauchline. He could have entered the village like a king. What a difference a year had made. Even James Armour made his obeisance, and, as a gesture of his new goodwill, he offered his daughter as an earnest of his change of mind. There was no talk now of writs or Sheriff’s officers. Burns accepted the ransom in as much as it allowed him to meet with Jean again – and the twins – but he was in no hurry to marry. Not while he had the whole of Scotland at his feet. He had his fame to enjoy as much as Jean Armour and, in any case, there were other beauties met with on the way, to flatter and make songs upon. There was Peggy Chalmers, for instance.

This was the first woman of quality and education who had looked on Burns as an equal, if not in rank, then in brains and attainment. She was also good-looking. Each flattered the other, and he even went so far as to propose to her during a visit to her relatives at Harvieston House, near Stirling. She, however, being more practical, turned him down in favour of an Edinburgh banker. A year later, writing to her from Ellisland, (and by now, married to Jean) he wrote:

When I think I met with you, and lived more of real life with you in eight days than I could do with almost anybody else I met with in eight years – when I think of the improbability of meeting you again in this world – I could sit down and cry like a child.

There was no doubt, he loved her – if only for eight days. She herself went off to India with her husband and eventually retired to live in France, but she never forgot her poet, and said that she might have given a different answer had he asked her again. Meantime, he continued his tour by travelling into the Highlands by coach with Willie Nicol, the school master, to visit Aberdeen and meet with Burnes cousins at Stonehaven. He had come into his fatherland in every sense, but he found nothing lovelier in this stern countryside than the Duchess of Gordon who invited him to dinner – but not Nicol. Burns had to leave the table in a hurry, to prevent Nicol running off with the coach, and the two friends returned to Edinburgh in a huff.

By this time, Burns was a national figure, a status he was to retain till the end of his life. His popularity fluctuated naturally, but from here on he was known to rich and poor alike throughout the land in a manner which is hardly paralleled even today, with fame being available at five minute’s notice. Without the benefit of TV, radio or even a reliable post, Burns was genuinely nationally famous inside a year. He had his detractors, even then, but they were powerless against theéclatwhich greeted this young man, when, between 1887 and 1889, he walked across Scotland like a god.