Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Luath Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

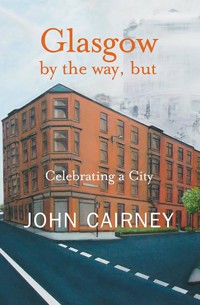

This is a book about Glasgow, but not your everyday history book. Glasgow by the way, but is a contemporary series of essays examining different aspects of Glasgow in a historical and cultural context, revealing a unique, amusing and sometimes critical, perspective of Cairney's beloved city. Those who remember John Cairney's performances and have read his other books will enjoy the insightful anecdotes from Cairney's career.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 377

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2020

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

By the same author:

Miscellaneous Verses

A Moment White

The Man who Played Robert Burns

East End to West End

Worlds Apart

A Year Out in New Zealand

A Scottish Football Hall of Fame

On the Trail of Robert Burns

Solo Performers 1770–2000: An International Registry

The Luath Burns Companion

Immortal Memories

The Quest for Robert Louis Stevenson

The Quest for Charles Rennie Mackintosh

Heroes Are Forever

First published 2006

Reprinted 2007

The paper used in this book is recyclable. It is made from low chlorine pulps produced in a low energy, low emission manner from renewable forests.

Typeset in Sabon 10.5

ISBN (10): 1-905222-50-5

eISBN: 978-1-913025-84-7

Printed and bound in Great Britain by Biddles Ltd., King’s Lynn, Norfolk

Text and illustrations © John Cairney

To my brother,Jim,who knows what I mean.

Contents

Acknowledgements

Foreword

Preamble

Introduction

CHAPTER ONE Bullish Beginnings

CHAPTER TWO A Transport of Delight

CHAPTER THREE All the Glasgows

CHAPTER FOUR Clyde Built

CHAPTER FIVE Local Heroes

CHAPTER SIX Sparrachat

CHAPTER SEVEN Alice in Barrowland

CHAPTER EIGHT The One, True Religion

CHAPTER NINE Speak the Speech

CHAPTER TEN One Singer, One Song

CHAPTER ELEVEN The Glasgow Greens

CHAPTER TWELVE No Room at The Inn on the Green

CHAPTER THIRTEEN Nostalgia for a Tenement

CHAPTER FOURTEEN The Flight of the Weegies

Epilogue A Glasgow Fancy

Bibliography

Acknowledgements

THE AUTHOR IS INDEBTED to the Right Honourable Lord Provost of Glasgow and Lord Lieutenant, Liz Cameron, MA for the favour of her foreword and to the good efforts on my behalf of Jim Mearns, one of her staff. I am also grateful to Bill Campbell and Peter MacKenzie of Mainstream Publishing (Edinburgh) for permission to use material from my biography East End to West End, and to Alastair Bruce for the use of extracts from my articles for The Tartan Umbrella.

Extensive reference was made to The Glasgow Encyclopedia, compiled by Joe Fisher, from the archives of the Mitchell Library and to Michael Munro’s The Patter, published by Glasgow Libraries and Canongate Publishing, Edinburgh, for specific facts and general information.

Immediate acknowledgement must be made of the first-rate work done by my editor, Catriona Vernal, of Luath Press.

I also wish to express my thanks to the many fellow-Glaswegians, neo-Glaswegians and non-Glaswegians who gave me the benefit of their opinions, anecdotes and downright lies about my home town. They are:

Bob Adams, Louise Annand, Strachan Birnie, Nell Brennan, Jim Cairney, Gordon Cockburn, John and Rosie Coleman, Michael Donnelly, the late Ian Fleming, Ian and Pat Laing, Gordon Irving, Starley Lee, Tony Matteo, Dr Ronald Mavor, Brian McGeachan, Jeanette McGinn, Dr Gerald McGrath, David McKail, John Moore, the late Anthony F. Murray, James Murray, Dr Mike Paterson and Philip Raskin.

Thanks are also due to Appleseed Music, New York for permission to reproduce lyrics by Matt McGinn, and to Scottish Screen for information on the Greens, to Will Fyffe (Junior) for details of his father and I Belong to Glasgow, to Dr James A. Mackay for his help with the Robert W. Service poem quoted and to Sean Cairney of The Scottish Banner in Australia for helpful sources. All other verse in the text, apart from traditional material, is my own.

Finally, I must acknowledge the New Zealand contribution, particularly the assistance given by David and Karen Curtis, Max Cryer, Katie Scott, Colleen Trolove, Katrina Hobbs and, most of all, the life support given me by my wife and first reader, Alannah O’Sullivan. I thank her for her pertinent suggestions at a vital stage in the project and trust that the finished volume you now hold in your hand repays all her efforts on my behalf.

I only hope that it is worth the experience, learning, talent, encouragement and co-operation given to me by everyone named above. If it isn’t, the fault is entirely mine.

John Cairney

Auckland, New Zealand, September 2006

Foreword

AT THE RISK OF embarrassing the author, I think it is fair to say that John Cairney is a bit of a Glasgow institution. His skills as an actor and an orator have enthralled many an audience and, like his native city, he has the great ability to re-invent himself. He has crafted careers in the theatre, in television and cinema and is now a successful author. Having made a world-renowned contribution to promoting the works of Scotland’s greatest poet, Robert Burns, he has in recent years turned his talents to promoting the works of Scotland’s greatest architect, Charles Rennie Mackintosh. John Cairney is indeed a man of many faces, but he is fundamentally a Glaswegian, and Glaswegians love Glasgow.

Glasgow is a city of contrasts where a great deal has been achieved and a great deal remains to be done but, as author Cairney shows, it is also a place where dreams are realised. This book tells many tales of the city on the Clyde and it carries the voice of one of Glasgow’s greatest sons. It is a tale of love and adventure, of struggle and progress and of insights and visions.

This year the people of Glasgow have been marvelling at the lovingly restored Kelvingrove Art Gallery and Museum. They have also celebrated the re-opening of their City Halls as a concert venue and many have visited the refurbished Kibble Palace at the Botanic Gardens. Their rebirth for new generations is a significant symbol of the city’s ongoing desire to re-invent itself to meet the challenges of the times. Glasgow is, of course, more than simply a collection of great buildings.

John Cairney understands – and demonstrates here – that Glasgow is a city of many voices. It is the welcoming city; a city of architecture, a city of parks, a city of sports but it is above all the dear green place enjoyed by its citizens. It can also be an angry city and it bears the scars of many battles – economic, social and physical – but Glasgow fights on and fights with all the wit and humour at her disposal.

Like John, I am a Glaswegian born and bred. We belong to Glasgow and, even without a drink on a Saturday, we know that Glasgow belongs to us and it’s a love story that lasts a lifetime. I have the greatest pleasure in inviting you to read this tale of John Cairney’s romance with Glasgow. It’s pure dead brilliant, by the way, but!

Liz Cameron, Lord Provost of Glasgow

Preamble

IN AUGUST 2004 I was in Edinburgh, appearing at that venerable city’s International Book Festival in Charlotte Square with my biography, The Quest for Robert Louis Stevenson. I shared a platform with Argentinian writer Alberto Manguel, who had also written about Stevenson in Under the Palm Trees, a novel based on Stevenson’s time in Samoa. At that time, my RLS book had inched its way, fleetingly, into the Scottish Bestsellers list, and my publisher, Gavin MacDougall of Luath Press in Edinburgh, decided to celebrate with lunch at the Doric Tavern in Market Street with, as he said, RLS paying.

We were joined that day by a mutual friend, secretary of the Edinburgh RLS Club, Dr Alan Marchbank. Talking about Stevenson as we did all through the first course, Alan happened to mention that, while in London and Paris between June and December 1878, Stevenson had written a series of articles for the Portfolio magazine which were published in book form as Edinburgh: Picturesque Notes. Stevenson, apparently, had been amused to find that not only had the volume managed to offend many of his fellow citizens, it also delighted the same number of Glaswegians, if only for the fact that the essays had annoyed their rivals in Edinburgh. Stevenson’s later comment regarding his compatriots, who had to live daily among the Old Town’s tall precipices and the New Town’s terraced gardens, was succinct:

Let them console themselves – they do as well as anyone else; the population of (let us say) Chicago would cut quite as rueful a figure on the same romantic stage. To the Glasgow people I would say only one word, but that is of gold: I have not yet written a book about Glasgow.

Well, at Alan’s suggestion, and with Gavin’s approval, I have, and here it is; part polemic, part history, part anecdote, part commentary, part fancy, part autobiography – but what the whole thing amounts to is a Glasgow quilt of many colours. Perhaps these very personal flourishes of mine might be more picaresque than picturesque, but that’s Glasgow.

Introduction

Every place is a centre to the earth, whence highways radiate or ships set sail for foreign ports; the limit of the parish is not more imaginary than the frontier of an empire; and, as a man sitting at home in his cabinet and swiftly writing books, so a city sends abroad an influence and a portrait of herself.ROBERT LOUIS STEVENSON

THIS IS MY SAY. It is a very personal say at that. This is my Glasgow – Glasgow as I see it now, now and then, and as I see it in my mind’s eye from the other side of the world. These verbal flourishes are by no means intended as a clean sweep; each is the touch of a brush on various aspects of my native city as they occur to me. Mine is only one man’s point of view, of course, but it’s the kind of happy journey that takes me down the broad avenues of verifiable fact while also giving me the chance to nip down the many side streets of anecdote. It’s from this memory-bank that people and places pop up to give flesh and blood to the bare bones of recollection. They also add some colour to the grey shades of objectivity.

Not that I can be anything other than subjective about the place where I grew up. I may now live thousands of miles beyond Glasgow, but the city has been a part of me for too long to allow me to distance myself completely. I still travel the world a good deal but, wherever I go, Glasgow is still at my centre. It is in every part of me, and has been all my life. Both of us may have changed a bit in that time, but I know the essential Glasgow boy is still in me yet, because I can hear his voice. He nags at my subconscious, reminding me of who I really am. He affects everything I say and do, even the way I think about things. It is this inner persona that gives me the continuing sense of where I come from no matter where I’ve been. It is an awareness I can never be rid of, so I’ve had to learn to live with it. The good thing is I can call on it wherever I am, and it appears like a genie from a bottle – the only difference being that I do its will, it doesn’t do mine.

So I have come to recognise that it will be part of me until I die: my Glasgow, my native city, my blessing, my curse, my great love and my pet hate, my dream place and my nightmare, my green and grimy city, my essential home place, my constant contradiction. Even its coat of arms displays a paradox:

Here’s the tree that never grew,

Here’s the bird that never flew,

Here’s the fish that never swam,

Here’s the bell that never rang.

That’s Glasgow: awkward from the start. The word ‘Glasgow’ itself is Gaelic from Glas cu, and it means ‘grey dog’ or ‘gray rock’, but to most Glaswegians, it’s just ‘Glesca’, the ‘dear green place’. But it is not just a place, it’s a state of mind. I can close my eyes and I see green – a ‘dear green place’ in all its unexpectedness. How can any conjunction of stone and steel, concrete and asphalt, brick and plaster, wood and plastic, remain so fixed in the mind as a thing of beauty? Because it is beautiful. Not pretty or nice or pleasant, but deeply beautiful, like an older woman who has eschewed lipstick and powder for something indefinable in the eyes. That’s my Glasgow: four thousand years old, but she still has that certain something.

So, if we’re going to talk about her, I’d better introduce her properly. Assuming that, like ships, all cities are female, then just like any woman, each has its own distinctive personality. If London is the world’s dowager queen mother, Paris is its wicked aunt and New York is everybody’s boisterous cousin. Rome is the next-door neighbour who takes in priests as lodgers. Glasgow has no pretensions to this first circle of great cities, unlike the status-conscious Edinburgh, but it is moving up fast in world ratings all the same, because Glasgow has recently discovered ‘style’ and is making it all her own.

It has taken over from Liverpool as the first city of pop, a veritable ‘Oasis’ for bands, and there isn’t a pop fan anywhere who doesn’t know that a former Rector of Glasgow University is Jim Kerr of Simple Minds. An association that doesn’t immediately come to mind, but one has to remember that Glasgow is the least Scottish of Scotland’s cities. In fact, it owes more in personality to Chicago than anywhere else; but the new boutique Glasgow, following hard on the recent Charles Rennie Mackintosh renaissance, is selling its own kind of modern cheeky-chic creativity. ‘You know but’ is cool, and ‘Jimmy’ has entered the language as an endearment, but the place itself, even if it is becoming a tourist Mecca, is still not entirely ‘respectable’.

The first thing to be said about Glasgow is that she is no lady. She talks too loudly and laughs too readily. Not like her big sister, Edinburgh, who knows how to behave on every occasion. Being older than Glasgow, Edinburgh had to stay at home and look after her old fatherland. She had more than one chance to marry, especially over the border, but never did. She knew where her duty lay. So, with pursed lips and nose held high, she carried on, smug in the knowledge that she was doing the right thing, and she made sure everybody knew it.

Glasgow, on the other hand, was always wild and caused her mothercountry a lot of worry when growing up. She could never keep her face clean, yet she never lacked for admirers. She had a child out of wedlock, called Dundee (they say the father was an Irishman), and Glasgow had to leave home. She went for a time to relatives in Belfast but soon came back to set up her own place. There are still strong family links with Ireland. Glasgow’s second cousin, Dublin, used to be close but there’s been an estrangement there. Dublin and Belfast have been bitter for years so the rest of the family won’t visit. They don’t want to take sides. It’s very sad. But that’s families.

According to Edinburgh, Glasgow is a disgrace to the family. But Glasgow doesn’t mind: she doesn’t need Edinburgh, which always annoys that superior place. However, Glasgow gets on well with her cheeky offspring, Dundee, who has just the same sort of spirit as Glasgow, whom she idolizes. Dundee would have liked to have been another Glasgow but never had that lady’s nerve. Dundee has her own style all the same and she doesn’t talk to Edinburgh either.

Perth, who is Dundee’s posh auntie, hates living so near this little Glasgow-on the-Dee and would rather live nearer Edinburgh. Just as Dundee idolizes Glasgow, Perth worships Edinburgh. She sees in her oldest sister all that she would liked to have been herself, but although she had the looks and the breeding, she hadn’t the inner steel of the born leader and is glad to leave all the decisions to the top girl in the family. Stirling was Perth’s twin, but not of the identical sort. They get on well enough but Stirling, being born first, is the stronger and always felt she should have been a boy. She is the only one who is not afraid to stand up to either Glasgow or Edinburgh and considers that she should be the natural capital of the country anyway. She is centrally-placed and has her own castle, ready-made for the new Scottish Parliament – and just think what that would have saved in time, money and bewilderment.

There is no doubt that Stirling has a case for being Scotland’s Second City, but she is too sensible to press the possibility too hard. She knows when she is well off. She has a comfortable home, a lovely garden and none of the worries of her older sisters, so she gets on quietly with her own thing. Aberdeen is much the same. She was swept off her feet by a rich American while she was still at school and is quite happy well away from the rest of the family, counting her money and waiting for the day she can move to Texas where all her real friends are. Inverness, the baby of the family, was a late child, quite unexpected, and rumour has it that the real father had royal connections, but they don’t talk about that in correct circles: the feeling there is that if nothing is said then nothing ever happened.

Like all families, the Scottish sisterhood of cities has had its ups and downs over the years, but they’re still there. With their various offspring, Dumfries and Kilmarnock in the west, Kirkcaldy and Dunfermline in the east, not to mention the new generation already growing up in the five grandchildren new towns – Livingston, Glenrothes, Cumbernauld, East Kilbride and Irvine – there’s room for a few surprises yet. But, honestly, I can’t see Edinburgh ever going west. Unless, that is, Glasgow decides to elope to Chicago.

Which Glasgow would never do, because she’s wedded to her river. She is a river city and has lived on and off the waters of the Clyde from the time that river rose out of the Leadhills in Lanarkshire and made its way through the infant Glasgow to the sea. This waterway was a vital element in the emerging township and proved a decisive factor in its growth. It still runs broad and deep through its centre following the sun west to the Tail o’ the Bank and the Atlantic Ocean. Glasgow has always looked westward to the Americas, just as Edinburgh has always looked east towards Europe. Like Liverpool, Glasgow made its fortune in transatlantic trade, but it chose tobacco and cotton rather than that human cargo imported from West Africa. This didn’t make the Glasgow commercial barons any better than their English counterparts; merely different.

Glasgow is the largest city in Scotland and ideally situated to be recognised as Scotland’s chief commercial centre, for it stands astride its river and looks out to sea and the rest of the world. It’s been doing that since it was a tiny fording place on the banks of the River Clyde, and went on doing so when it became a great trading post, and then an international seaport and finally an industrial metropolis. It was once the Second City of the Empire, but that empire is now long gone, as are the industries. However, Glasgow has struck back and is rapidly emerging as a tourist attraction, an international arts centre, and the true cultural capital of Scotland.

It’s hard to believe now that it first achieved fame as a beauty spot. As early as 1650, proceedings in Parliament drew the happy comment: ‘The town of Glasgow, though not so big, nor so rich, yet to all seems a much sweeter and more delightful place than Edinburgh.’ Who can disagree with that? Samuel Pepys came north in 1682 as part of the train of the Duke of York (the later King James VI and I) and found Glasgow to be ‘a very extraordinary town for beauty and trade, much superior to any in Scotland.’ But Pepys found the people much less attractive. He had ‘a dislike of their personal habits... a rooted nastiness hangs about the person of every Scot (man and woman).’ Only a Londoner could say a thing like that.

Daniel Defoe was much more flattering, but then he was an English Dissenter and came to Glasgow straight from prison in 1726. He called the town ‘the emporium of Scotland... stately and well-built, standing on a plain in a manner four square... it is one of the most beautiful places in the country.’ Defoe came back several times, which is a compliment to any place. He was also one of the first to see the possibilities in a Forth and Clyde Canal. Defoe had a sharp eye, an advantage to any spy. By 1770, Tobias Smollett, a Dumbarton man, could also see the possibilities in Glasgow, referring to it as ‘the pride of Scotland, which might pass for a flourishing city in any part of Christendom.’

Scotland’s National Bard, Robert Burns, made five visits to Glasgow between 1787 and 1791, on book business with John Smith in St Vincent Place and always stayed at Duthie’s Black Bull Inn in Argyle Street. From there he wrote to his Edinburgh amour of the time, ‘Clarinda’, who was actually a Glasgow girl, Nancy McLehose née Craig, the daughter of a Glasgow surgeon from the Saltmarket. Burns met up with Captain Richard Brown in Glasgow for ‘one of the happiest occasions of my life’ – meaning they both got very drunk. It was Brown, a sailor, who had earlier given Burns the idea of becoming ‘a poet in print’, so we have much to be grateful to Captain Brown for. Betty, Burns’ illegitimate daughter to Anna Park of the Globe Inn in Dumfries, grew up to marry a soldier and settled down in Pollokshaws. Following the poet’s death in 1796, Betty received £200 from the fund set up for the Burns family. This was the poet’s only gesture towards Glasgow.

Another poet, William Wordsworth, came to Glasgow in 1803 with his sister, Dorothy, and good friend and fellow-poet, Samuel Coleridge. They were on their way to pay their respects to Burns’ grave in Dumfries and visit his Cottage in Ayr. In Glasgow, they stayed at the Saracen’s Head in the Gallowgate, but neither poet was inspired to write anything about the city, though Dorothy did note in her journal that ‘the streets were as handsome as streets can be’. JJ Audubon, the American ornithologist, arrived in 1829 with copies of his famous book of birds but only managed to sell one copy, and that was to the Hunterian Museum at the University. Mr Audubon was not impressed by Glasgow’s apathy to American birds.

William Thackeray, in Glasgow to give a series of lectures in 1852, was another who did not take to the city: ‘What a hideous, smoking Babel it is, after the clear, London atmosphere, quite unbearable.’ He also took exception to the large number of what he called ‘Hirishmen’ he heard in the streets, no more than many Scots themselves did. Nor was Charles Dickens a Glasgow admirer. He read from his works there in 1861 and 1868, but thought it ‘a dreadful place’. He also added that ‘it rains as it never does rain anywhere else.’ Did he mean that the rain went up?

It is interesting to note the graph of disparagement grow as Glasgow developed from the almost sylvan seventeenth and eighteenth centuries to the industrial effects of furnaces and smoking chimneys in the nineteenth. Even the statues turned ebony black in the atmosphere. This actually improved many of them, but goodness knows what it did to living lungs. That not so eminent Victorian poet, William McGonagall, came to Glasgow from Dundee to be entertained by a group of University students at a banquet in Dennistoun. After much mock-ceremony, he was duly dubbed by them Sir William ‘Topaz’ McGonagall, Knight of the White Elephant of Burma – and awarded the status of the best worst poet in the world. The irrepressible McGonagall was not deterred. He knew he would be remembered. And he was right; he is genuinely famous for failing, which is perhaps what Glasgow liked about him. What we do know is that he liked Glasgow:

O, beautiful City of Glasgow

That stands on the River Clyde,

How happy should the people be

That in you reside.

For you are the most enterprising city

Of the present day

Whatever anybody else might say.

It was all too good to last, and it didn’t. By McGonagall’s time, heavy industries had encroached on the green place, and it was hard to see the town for smoke. It was no longer picturesque. Every street seemed to sprout a factory chimney, or ‘chimley’ as the natives called it, and every tenement contributed its noxious mix to the deadly canopy that hung over everything and everyone. What had been genuinely picturesque so recently was gradually enveloped in soot, grime and engine oil, each of them conspiring to disfigure old, grey stones that had stood since the Romans. However, plenty of lovely money was being made by some out of the unsightly conditions, and the mercantile princes of plunder made mansions for themselves along the Great Western Road – which might as well have been called the Great Gatsby Road such was its splendour. In 1889, the Doge of Venice’s Palace was recreated by William Lieper on Glasgow Green as a carpet factory for Mr Templeton. This was Glasgow hubris at its best – or worst – but when it wanted the best, it got it.

If the nineteenth century was good for the Glasgow businessman, it wasn’t so good for the ordinary Glaswegian who was paying dearly for trade expansion and prosperity. The incoming Highland and Irish migrants, who had flooded into the city to escape either absentee English landlords or the potato famine, were crowded into the new tenements like herring in a box. New tenements were sprouting up all over the inner city, trying to keep up with a population that seemed to be growing by the hour. Glasgow was gradually evolving its own kind of people, and most of them were below the poverty line. Many died early among the muddy streets, running drains and damp walls. In order to survive at all, they had to develop a close neighbourliness against their common plight, a spirited defiance of their living condition. This is how they gained the term ‘gallus’, a kind of esprit de la rue, a streetwise insouciance, which Glaswegians have retained to this day, marking them out from all other Scots – especially those in Edinburgh.

Unlike the ‘Edin-buggers’, the Glasgow proletariat has no great history to speak of, and the eastern bloc rather looked down on the western bloke. It still does. Everyone looks down on the Glaswegian for he is generally smaller than most. The city’s old regiment, the Glasgow Light Infantry, formerly out of Maryhill Barracks (now a shopping mall), were Glasgow’s own Ghurkas, and just as fearsome in their bantam way. Have you noticed that all our boxing champions, from Benny Lynch to Jim Watt, were lightweights? Nonetheless, they weigh heavily in terms of Glasgow’s regard for their own. They don’t need Edinburgh’s cobwebbed ghosts.

Thomas Moore in his lovely song, Believe Me If All Those Endearing Young Charms, tells us that ‘the sunflower turns on her god, when he sets, the same look which she turned when he rose’. This meteorological balance doesn’t seem to apply along the M8 motorway linking Glasgow and Edinburgh. Or is it that there is just a lack of sunflowers in Lowland Scotland? Since the sun is the source of all living things, there may be a co-relation between the effects of the sun’s rising or setting on the character and personality of those who see it first and those who see it last. At any rate, east is still east but west is best – for some of us. This westward demographic inclination was just as evident in ancient times. If the Persians looked west to Egypt, the Greeks did likewise across the Ionian Sea to where the Italian coast lay just over the horizon. To them it was the edge of the world with the Great Unknown beyond it. What was there, in fact, were the Roman legions and by the beginning of Christendom it was they who ended nearly a thousand years of Hellenistic sway.

Roman power and influence spread over the whole known world of that time before its sceptre went west again into the hands of the Germanic Charlemagne, who became the first Holy Roman Emperor of the West by 800AD. It was the Teutons, moving west once more, who gave the Roman Londinium its Celtic name, London, at a time when Arthur’s Seat was still vacant and Dunedin was little more than the rock it stood on. Glasgow was then no more than a wee green spot on the banks of the Molendinar Burn where it trickled into the Clyde. All this is discoverable fact borne out by history, but if a similar westward instinct thus should ever manifest itself in Scotland during the second millennium then it is quite possible that the capital itself might move west to Glasgow.

Changing the capital of a country is not a new idea: once upon a time, Dunfermline ruled in Scotland, so did Stirling. It’s almost accepted today that in any country there are two capitals, one official and one actual. We know that in the United States the talking is done in Washington but the action takes place in New York. The same applies to Ottawa and Toronto in Canada – with Quebec having nothing to do with either of them. Similarly, Germany has Bonn and Berlin, while Russia has Moscow and St Petersburg. Most countries have a working city and a showplace city, a weekday capital and a Sunday one. Except in England, where London, arguably the most famous city in the world, is still the capital and hub of the country, if not of the whole British Isles. Paris comes a close second, although you don’t say so in France. To the French, Paris is the capital of the world.

The point is that this division of purpose, the separation of function into the executive and the consultative, is perhaps not such a bad thing. By each playing to its strength, they minimise their respective weaknesses. Parliament works this way with the House of Lords as does the US Senate with Congress – or at least they try to. The same applies to Anglo-Saxon Edinburgh and Celtic Glasgow, the prim office and the untidy factory, the front room and the kitchen – sharing the same house but not speaking. So near and yet so far. What kind of country would Scotland be if we swapped things round so that Glasgow became the capital and Edinburgh the workplace? It would be a lot more fun for one thing. Except that we would never get anything done. Edinburgh would go in a huff and Glasgow would probably bankrupt the nation by holding a citywide party to celebrate its new status. Nevertheless, a combination of Glasgow’s zest and Edinburgh’s class would make a formidable capital. Perhaps it could be situated near the middle of the M8. They could call it Shottsville – or Bathgate Brazilia? Nae borra. No, on second thoughts, it might be wiser to leave well alone and keep things as they are.

‘Suit yersel,’ as the wee man said.

CHAPTER ONE

Bullish Beginnings

THE BULL STOPS HERE

EVERYONE BELONGS TO somewhere and I belong to Glasgow. I am only one of that myriad of mongrel ingredients that have gone into Glasgow’s ethnic make-up over the last four thousand years. The demographics involved are colourful to say the least, but this very lack of pedigree might explain the city’s particular vitality and exuberance. The city’s aboriginals, after all, had painted faces and a fierce fighting tradition – so what’s changed? The Celts, (pronounced with a ‘K’) emerged from the Albanian mountains in the early morning of civilization and moved up through its young days via Morocco, Spain, Brittany, Cornwall and Wales and the Lake District before arriving in North Britain in what is now the Lowland West of Scotland at a point then called Cathures, where the Molendinar Burn runs into the Clyde.

Pursuing them all the way were the Romans, those proto-Italians, who, under orders from Emperor Antoninus Pius, got as far as the outskirts of Old Kilpatrick before being beaten back by the midges, that very underrated last line of defence for all who live beyond Hadrian’s Wall. The ferocious Celts forced the Romans to build the Antonine Wall, to help keep the natives (and the midges) out. Because of their painted faces, the Romans dubbed these spunky people the Picts, and their descendants can still be seen strutting the streets of Glasgow today. Inner city types; bantam, lithe, dark-haired men who don’t paint their faces but often bring a blush to other people’s.

The mass exodus of the Romans after nearly five hundred years left the way clear for the next invaders, the Gaelic-speaking Scots from Ulster led by King Fergus in 503AD. These Scots who had already been converted to Christianity by St Columba of Iona, overcame the Britonnic Celts of Strathclyde, and finally settled in Dalriada, an area in Kintyre first mapped out by St Ninian. It could be defined more or less as the region containing the city of Glasgow and its surrounding environs. Ninian’s culture in the east of Scotland had produced The Goddodin of Teutonic Edinburgh which was the basic source for the Arthurian legend. Who knows, King Arthur might have been a North Briton? After all, Arthur’s Seat is right in the city centre. While St Cuthbert looked for other Angles to bring Christianity to the region around the Forth, the Picts, under King Brude, moved north and operated north of the Forth and Clyde mainly out of their fort in Inverness.

This then was the state of sixth-century Scotland when Fergus died in 525 at Culross Abbey. One of the monks there, Kentigern, was instructed to harness a bull to a cart and place the body in it. He was then to bury the king wherever the bull stopped. It was hardly a papal bull, but it was an order and Kentigern dutifully complied. Both the monk and the bull must have had stamina because they walked fifty miles or so across lowland Scotland before coming to a halt at Cathures, the Celtic settlement on the Clyde. Here St Ninian had already prepared a graveyard so Kentigern duly installed Fergus as its first client, and himself as its first priest. There is no record of what happened to the bull.

Tradition tells us that Kentigern was the illegitimate son of a princess, who had been cast out to sea in an open boat by her father when he found out she was pregnant. In his anger and shame he left her to the mercy of the elements, which washed her up at the Culross monastery on the shores of the Forth. The monks took her in and later trained her boy Kentigern for the priesthood. This was the boy who became the man, Mungo, who eventually became Glasgow’s patron saint and a figure on its coat of arms together with the bird, the bell, the tree and the fish.

Each of these symbols is linked to the miracles Mungo is reputed to have worked in his life of more than one hundred years. He predicated that a lost ring would be found in a salmon’s mouth. It was presumably a freshwater fish, but this sort of legend has to be taken with a pinch of salt. Another involved a hill that rose under him as he preached, while yet another told of the branch he had broken off from a tree that would burst into flames at his touch so that he could light a fire. There is no reason given why the bell never rang except that it might have just lost its tongue. Legends like these last for all sorts of reasons, none of which need be true.

Meantime, young Glasgow was stretching through her green years taking in and taking on various strains and septs that attended the line of Scottish kings stumbling through the Dark Ages. Normans, Saxons, Angles and Danes were all racial stages up to and including the fourteenth-century Robert the Bruce, who was really French but spoke conversational Latin. Three hundred years later the Continental connection was maintained by Bonnie Prince Charlie, who brought his rabble of Highlanders down to accept the quiet surrender of Glasgow to the Jacobites in 1745. The prince and his tartan army encamped at Shawfield and made as good a show on Glasgow Green as ever the carnival was later to do during the Glasgow Fair.

Not every Highlander came south waving a claymore. Some were not even Jacobite and it was the more sober, God-fearing Presbyterian Highland scholar who now walked the twisting miles from the north. He was to leave his inky imprint not only in Glasgow but all over the world as the archetypal classroom dominie. Little more than boys themselves, they brought their Bibles and their bags of oats to the university and from there graduated to become indispensable cogs in the education machine. Every Glasgow school had its Highland teacher, usually in the English Department, specialising in the Classics, imposing his severe standards on generations of little town tikes who ‘crept unwillingly’ to listen to precisely enunciated knowledge imparted in tones that made everything sound like a sermon. The late, great, comic actor Duncan Macrae was such a teacher, and Roddy MacMillan, also a fine Glasgow actor in recent times, and a fellow-Highlander, was one of his pupils in Anderston.

It was from this same Highland stock that a good proportion of Glasgow’s future population came, and at least half of its intimidating police force. A new clan of constables emerged throughout the twentieth century, each as tall as a pine tree, and often just as thick, but offering a police image that was daunting. Just imagine an arboreal giant in heavy boots and large helmet charging at you, baton in hand. You never saw his eyes under the helmet. Perhaps he didn’t have any to speak of, which was why he blindly followed orders to the letter. Still, the big Highland bobby was an unmissable feature of street life in Glasgow until the ‘Z-car’ sixties, and he kept those same streets as clean as the Corporation Cleansing Department ever did.

The Gaelic Glaswegian gave us words like ‘glaikit’ from gliogaid and ‘skelp’ from the Gaelic sgealp. However, the most used Gaelic word in Glasgow appears to be ‘ach’ or ‘och’, which Glaswegians have adopted as their own. While gregarious Glasgow didn’t adopt the Highland clan system, it developed its own style of street co-operative, which was more or less the same thing, but with smoke and soot in place of Scotch mist. The tartan territory was the above-mentioned Anderston, which was about as far south as the Highlanders went in the city. Here they built their own community with its own Highland Hall near the once beautiful Charing Cross, but the main social centre for the Northerners was the Hielandman’s Umbrella. This was the Central Station’s railway bridge over Argyle Street where the ‘tcheuchters’, as the other Glaswegians familiarly called them, could shelter from the rain and hear news from home. Highlanders rarely ventured to the east or south of the city.

It was to the south that the Jews came. It was only when many of that old race moved from Holland and Germany towards the end of the eighteenth century that Glasgow could be said to get down to business. The Jews originally settled in Edinburgh but it did not take them long to see the error of their ways and they soon made their way west. One can see the development of these intrepid pioneers in terms of their synagogues and burial grounds, both of which became larger with each generation. It was the end of the nineteenth century which saw the next Jewish surge when the incomers arrived direct from Poland and Russia and settled in the Gorbals. Shops were opened and cash registers chimed as fortunes were founded on hard graft done at the counter and the cutting room. What is called the ‘rag-trade’ grew out of the rags that many of these specialist tailors and garment workers had arrived in.

They did not stay ragged long. Money spoke louder than Yiddish and this new status allowed the Jewish community to make a formidable input into the life of Glasgow, especially its culture. This Jewish flavour has been a very valuable and exotic ingredient to the Glasgow mix, and the city continues to benefit from it, as do many countries far removed from Israel. It is largely thanks to its Jewish population that Glasgow still has its theatres. Jewish involvement via the Goldberg family, especially Michael Goldberg, made possible the development of the Citizens’ Theatre from playwright James Bridie’s embryo at the Athenaeum to a civic playhouse now enjoying an international standing.

The Goldbergs were also behind every second art gallery in the West End. They are typical in recent times of the enlightened Jewish contribution to the arts in the city. Sir Isaac Wolfson has also played his part by donating major benefactions to Glasgow University and his name graces a whole new campus on the north side of the city. Dr Benno Schotz, the Queen’s Sculptor in Scotland, was a Jew who came to Glasgow by way of Estonia in 1914, and rose to own a studio/mansion in Kirklee at the Botanic Gardens. Benno brought his east European elan to a Glasgow that was ready-made for him. He had come through pogroms and exile to get there but he could now laugh it all off. The best thing he had done, he always said, was to come to ‘Schotz-land’ as he called it, and to ‘Class-co’, which he said he loved for its ‘brio’.

In 1968 I sat for him for a bust as Robert Burns. I was given, at the same time, extra-mural tuition in the arts just listening to him talk. I was clay in his hands, in every sense. When I look at the bronze today it’s his twinkling face I see. He phoned me at my mother’s flat in Dennistoun on his 92nd birthday and chuckled into my ear, ‘I thought the Lord would take me in the night. I asked Him to, but He didn’t listen to me, so I have a whole day I didn’t expect. What am I going to do with it?’ Benno, with his Glasgow-Estonian zest, made it seem as if he’d been given a huge bonus of a fresh day – at 92. All he wanted to do by then was join his wife, Millie, who had been in Abraham’s bosom for some time, but as long as he had breath, he had life and he filled his day. As it happened, he went to his Millie not long afterwards, so God must have been listening after all.

Beryl Cutler was our Jewish doctor in Parkhead. He was also a Hebrew scholar specialising in Jewish pre-history. Beryl did not live as long as Benno but he packed a lot into his day-job serving the poor Irish for pennies in post-war Parkhead. Between calls, he went back to his books like Faustus. In his study he was trying to fathom the complexities of ancient man in the Middle East, and in his surgery he was doing much the same with his patients in the East End. Whenever I went to collect medicine for my mother or father, Dr Cutler would always discuss what I was reading at the time before signing another prescription. When I later went to university, I used to see him in the Reading Room on his day off, though I could never see much of him as he was always halfhidden behind a large pile of books.

When he made a house call at Williamson Street during my father’s last illness, I would hear them discussing Martin Buber and Kierkegaard in the kitchen and debating, sometimes heatedly, the idea of Man’s direct relationship with God. I remember my mother was quite impatient with these debates. She wasn’t into religious existentialism. A quick ‘Hail Mary’ did it for her. All she wanted to know was if my father’s blood count or pulse rate was up or down, but Beryl Cutler attended the mind as well as the body. He knew that was the healthier part of my father. I can’t remember much of their conversations but I do remember their laughter. Beryl Cutler wasn’t a big man but his mind was huge by any standards and he gave of it gladly to anyone interested. And he did so with laughter. He knew its importance.