6,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

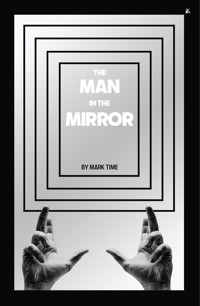

- Herausgeber: Antelope Hill Publishing LLC

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

Joe Blaine is an average young man, but after a series of catastrophic events unfolds in his life, his world becomes forever changed. Launched into a perilous journey he never would have chosen—but one he sorely needs—Joe learns the true value of struggle in a time when everyone would deem it pointless. In Joe’s world, gone are the days of a typical coming-of-age story, as society obscures truth and abuses its people. Instead, Joe is forced through adversity to take an honest look at himself and reconcile all his actions and inactions with the Man he sees staring back at him. As a result, Joe discovers that what seems like mere chance or inevitability is in reality the intersection of the deliberate actions of others and the guiding hand of Providence.

Fast-paced, action-packed, and thought-provoking,

The Man in the Mirror takes the reader on an adventure along with Joe as he not only learns the truth about his society but also takes control of his own life. Antelope Hill Publishing is proud to present Mark Time’s first novel,

The Man in the Mirror, a bold contribution to the world of dissident fiction.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Ähnliche

The Man in the Mirror

THE

MANIN THE MIRROR

A NOVEL BY

MARK TIME

J A C K A L O P E H I L L

Copyright © 2023 Mark Time

First edition, second printing 2023.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or used in any manner without the prior written permission of the author,

except for the use of brief quotations in a book review.

The story, names, characters, and incidents portrayed in this book are fictitious. No identification with actual persons (living or deceased), places, buildings, or products is intended or should be inferred.

Mark Time can be contacted via Telegram (@Mark_Time_Author )

or followed on his channel: t.me/MarkTimeAuthor

Cover art by Swifty

Edited by Margaret Bauer

Layout by Margaret Bauer

Published by Jackalope Hill

The fiction imprint of Antelope Hill Publishing

antelopehillpublishing.com

Paperback ISBN-13: 978-1-956887-82-2

EPUB ISBN-13: 978-1-956887-83-9

But if any provide not for his own, and specially for those of his own house, he hath denied the faith, and is worse than an infidel.

1 Timothy 5:8 KJV

P A R T IT H E T H R E S H O L D O F A C T I O N

1THE ROOTLESS URBAN PILGRIM

He was an average Joe. An average is gained by dividing the total value of a body of data by the number of data points. Joseph Arthur Blaine was a data point, ever being divided and aggregated against the body. His ancestors grew up in times of immense prosperity. In those days, men competed for jobs against other men in their own town. In Joe’s day, he competed against the mighty throng of all humanity. The data field was much larger for Mr. Blaine.

Generally speaking, Joe avoided returning to his hometown in the heartland. Every time he did, it seemed a little more hollow, a little less friendly, a little more. . . . Joe couldn’t quite articulate it. All animals have a certain sense for impending doom. The decline was more easily observable after a period of absence. The longer Joe was away, the worse his hometown seemed to get. Despite his best attempts at denialism, the rot scintillated abject terror into his unspoken thoughts.

On his last visit home, he decided to visit the old mall. Most of the shops were shuttered. A few urban, streetwear clothiers plied their trade among those perennial last survivors of brick and mortar’s death: the supplement and soap shops. Everyone in the mall was a stranger to Joe. Not that he ever was acquainted with the regular attendees at the consumer temple, but this new crop seemed particularly . . . that same feeling Joe couldn’t articulate. The tender caress of the smooth jazz emulsified with the inhuman yelps of brawling youths next to the cinnamon roll bakery. Joe fled the mall to drive through the neighborhoods where his high school friends used to live. Many of the houses were now vacant. The town was hemorrhaging people due to flight and Naloxone doses that came just a little bit too late.

Where do they all go? Joe mused as he reflected that most towns in the heartland were like his own.

He now lived in MLK Jr. County, a sort of amalgamation of several cities in southern California, which merged together as they expanded rapidly due to both foreign and domestic immigration. City-counties like these exerted greater administrative control over the area than the previous layout of cities filled in with suburbs, ensuring a more equitable distribution of resources.

A reluctant surfer of Big Tech’s flowing tide, Joe’s own life was at slack water. The rent for “his” 850 square foot home occupied the lion’s share of his expenses. Joe was married to a gal he uprooted from the same hometown. Both made their hajj to the big city after they got married. The funny thing about pilgrimages is that one usually returns home afterwards. That gutted husk didn’t exist for Joe and his wife Jill anymore.The pickings in the big city seemed better than the assortment of minimum-wage distractions and asbestos-riddled huts in their hometown. If opportunity hadn’t already moved overseas, it was crammed among millions of teeming souls on the coast. The reality of their newly-acquired surroundings hit them just as they realized they could not afford to move again. Joe and Jill were in for the duration.

In their new location, their only sense of community consisted of going to a faceless megachurch and connecting virtually with the same friends they had back in college. The paradox of being lonely among millions crushed them. They both grew up as Christians and still went to church on occasion even in their new locale. A church Sunday was as follows: at 7:30 a.m. he’d jolt awake at his usual weekday wakeup time. By 7:31, he’d breathe a sigh of relief and return to sleep. A few hours later, Joe would wake up his wife and skip breakfast. Fighting traffic for thirty minutes on a nineteen-mile section of freeway eventually delivered them to Love Today Assembly. Upon entering the auditorium with thousands of nameless others, Joe would wince at the drums. At the conclusion of precisely three songs that sometimes mentioned Jesus, a thirty-something-year-old man wearing a flannel, skinny jeans, and a beanie hat entered the stage.

“Hey guys,” he would say into his slim ear mic, “who’s feeling God’s love this morning?!”

This exhortation was usually followed by cheers and affirmative drumming. After drifting into vague platitudes about being “a good person,” the pastor would exit stage left and drive away in a Mercedes S-Class while his minions collected tithe. Calling it church was perhaps an exaggeration, though Joe and Jill didn’t know any better.

Joe’s bungalow was rented from a national property acquisition company. His landlord did not have a name but rather went by Sun Street Homes. Sun Street owned half of the rental market, while Golden State Housing owned the other half. When searching for a home, his rent choices consisted of a majority of his income or a slightly smaller majority of his income in the “urban” part of town with the “bad school district.” Owning a home was out of the question when Sun Street and Golden State started bidding. His wife worked as a secretary in one of the skyscrapers downtown to make up the rest of the bills. Kids were on hold for the time being as their twenties ticked away. The years seemed to rack up faster than they could shovel away their collective mountain of debt.

“Just until we’re a little more settled,” they reassured themselves without any true definition of “settled.”

Joe was rootless. His city was interchangeable with a dozen others. On the one occasion he traveled abroad, he was filled with a deep sense of despair to learn that the “authentic” shops were selling the same Chinese goods as the stores back home. The skyline of his city was only recognizable by its slightly different arrangement of productivity prisms. Joe was much like his city. When he looked in the mirror, he had no discernible description besides what his overlords dictated to him. His height, weight, hair color, and eye color jumbled together in the stew of the unknown. His indistinguishable degree had been awarded to thousands before and after him. His resume more resembled excuses to hire him rather than reasons. Joe’s conditions were the result of carefully planned algorithms and think tanks. The sanitized life appointed to him bounced his shell along the guard rails toward the gutter at the end of the lane only to be recycled and bowled again.

Yet latent within him was something else he couldn’t articulate: shackled, tamed, castrated, domesticated, this force toiled within Joseph Blaine and tore at the fleshy walls of its prison to escape, attempting to make contact at every turn, but the wax of social acceptability hardened into an exoskeleton around his soul. Joe avoided eye contact, kept his head down, and hoped he could slip through the cracks long enough to retire in four decades, but soon there would be an immolation of his personhood. The forbidden instincts within him would lay roots in the same way a great tree tunnels beneath a foundation and cracks it asunder.

2BROTHER TO HIM WHO DESTROYS

“Number 243, now calling number 243.”

Joe checked his ticket and glared at the number 389. By now the ticket had been folded, unfolded, twisted, rolled, and crumpled. He had been waiting for nearly two hours for his housing voucher. This endorsement was needed for his demographic to live in advantaged areas and required annual recertification. Joe reflected for a brief moment on the cliche of being “just a number” but ultimately thought little of the metaphor.

When, at any time, has the commoner not been a number? he joked in his head.

He had no pretensions of tearing this fact down or waxing intellectual about class relations. Joe’s self-awareness of his cog-dom was free of the usual side effect of a desire to change it.

All of history is hierarchical. Can’t have too many chiefs. He paused for a moment to wonder if the latter expression was in poor taste even though he left off the descriptor for the chiefs’ underlings.

“Number 345, now calling number 345.”

Another hour and a half passed. It neared eleven in the morning. The second hand of the clock danced in circles on the wall. It was illiterate yet wrote of profound dread in the minds of those who waited and watched. Joe watched in horror as the employees at the counter began to shutter the windows and go to lunch. His eyes drifted to the pasted brochure on the counter: “SUICIDE PREVENTION AND AWARENESS. You are not alone, there are resources to help you. We care about. . . .”

The lump at the counter pulled a magnetic sign from under the desk and slapped it over the brochure with an inarticulate grunt. It was upside down, but Joe knew what it said: “Lunch hours from 11:00 a.m. to 1:00 p.m. Your request is very important to us, and we will be with you shortly.”

Joe’s boss agreed only to give him the morning off. Under constant threat of being outsourced, his job security teetered. He needed the housing recertification by next week or he would be evicted. The Office of Inclusive Housing Opportunities (OIHO) only held customer service hours in July for three weeks prior to the recertification deadline. However, given that the paperwork takes a week to process, nearly all applications in the third week would be denied. It was Friday of week two. He carefully weighed his options.

Okay, I can wait here, get my paperwork signed, pay the fee, and get my application in a week before the deadline. I don’t think Mr. Raab would actually fire me. I’d probably get a slap on the wrist and then move on, Joe mused as he contemplated the anxious scuff marks on the faded linoleum floor beneath his chair.

His phone buzzed. It was a text from his co-worker, Tyler.

“Hey man, Raab wants everybody back at the office asap. I’ve seen a lot of corporate dudes. Seems pretty important. Where are you at?”

Joe replied, “No way. I’m at the OIHO office getting my recert. I have to do this today or it’ll be too late.”

“He seems to be in a firing mood, bro. Up to you. There’s a big meeting at 11:30.”

Joe swore to himself under his breath.

“Can’t have a house if I don’t have a job,” he grumbled aloud.

He rose from the chair and gathered his things. The others in the waiting room looked at him with two emotions. One was of sympathy for his plight. The other was of relief for his removal from the queue.

3THE BEIGE HOLE

“Hey, team, gather ’round.”

Joe always rolled his eyes when Mr. Raab called them a team. The gray cubicles sat anchored around the sullen assembly in a sea of stain-concealing carpet.

“I want to open up by saying that it’s been a real privilege working with y’all.” Raab always waxed folksy when he delivered bad news. He was a taller man who played up being from Texas, but he knew nothing of the place outside of Austin. His carefully preened brown hair sat over a constant expression of contempt.

Raab continued, “We’ve seen great numbers . . . great numbers.” He was well-versed in the compliment sandwich technique wherein bad news is flanked on either side by positive reinforcement, though he seldom excelled in making the bread and usually just skipped to the meat. “Look, numbers are great, but corporate is having some issues with this branch’s size. The economy is struggling, and competition is stiff out there. I’m just going to break it to y’all. Corporate has decided to move most of our location’s workload to our Mumbai office.”

“Outsourcing!” Tyler whispered to Joe.

The gathering let out a few gasps and groans. One woman started to sob.

“If it were up to me”—it wasn’t—“I would keep every one of you employed”—he wouldn’t. “I’ve posted a list on the corkboard in the break room of the retained and laid-off staff.”

Most of the employees began murmuring and shuffling toward knowledge of their fate.

“Oh, uh, one more thing. . . .” All stopped just for a moment and gave dour stares. “I’m very proud of the work you guys have put in.” He nearly forgot the second slice of bread.

“Great, he’s proud of me. Let’s see if he’s going to keep paying me,” muttered another drone next to Joe.

As he walked toward the break room, he peaked at the memo in Raab’s hand. It was dated for the previous Tuesday. In lockstep with corporate policy, layoffs were always implemented on Fridays.

The break room was a beige hole in the wall where employees would come to huff the fumes of stale coffee and that indescribable smell all office microwaves gain after years of ramen, spaghetti, and dry chicken imparting their foulest qualities. Those at the front of the pack began checking for their names on the bulletin. The first one, a lady from accounting, breathed a sigh of relief and exited the room hoping to not look too joyful. Joe was about in the middle of the despondent procession. The line of employees shuffled one by one past the list in the same manner and pace funeral goers pay their respects, tears and all. As he neared the front, his pulse pounded. Joe feared the worst. His performance was middling among his coworkers at best. Economically speaking, there was no reason to pay him this much for his productivity when Mumbai was far cheaper.

Tyler stood several spaces ahead. He made it to the front and ran his finger down the list of names until it rested on his. “Canned!” he jolted. “Couldn’t even tell me himself.”

Tyler was among the top performers in the office but, alas, demanded too much money. He stormed out of the breakroom. As he brushed past Joe without a word, the other less successful employees darkened. Next in line was Courtney. Her son had a mental disorder, and she devoted much of her paycheck to his childcare and medication. The company’s health insurance was cut last month to reduce costs. She had no reaction. Not a soul in the room could discern her face. Courtney simply walked up, stood for a second, and walked out stoically.

Joe was now only a few spaces away. He strained his eyes to get a preview of his judgment. At last, he made it to the front. His status was no surprise to him, but the wretchedness overtook him nonetheless. On autopilot, Joe drifted to his cubicle to gather his things. He stood behind his chair and took in the scene. The blank computer monitor sat impassively among a few knickknacks meant to evince a modicum of personality. Joe peered above the cubicle’s ramparts at the other severed wretches. The mixture of tears and frustrated sighs swelled into a despairing requiem. As Joe collected the items on his desk, he thought about the countless hours he spent bound to this felt cage. If any of his ancestors could see the way he clacked endlessly at the keyboard among tight, enclosing walls, they would have assumed he was imprisoned or enslaved.

Joe floated out of the office building in a daze to his car. A million things rushed through his mind as he sat in the ripped leather cradle of yesteryear’s luxury sedan. Emotions began swelling like magma beneath the crust of his shell. Closing the door, he punched the steering wheel and broke the logo. The horn let out a pathetic whimper. Next on the kill list was the sun visor. Overcome with violent rage, he awoke the ancient engine and sped from the parking spot he had spent twenty minutes finding after returning from the OIHO. A hapless pigeon was his next casualty. Joe let out a tortured scream, resonant with the groaning V6.

Sweat pouring out of him in the summer heat without functioning air conditioning, Joe rolled the windows down as he drove to nowhere. He checked his phone at the next stoplight. With anxiety, he realized that he had broadcast his breakdown to his wife’s voicemail via butt dial. Panicked, Joe ended the call without clarification.

“Oh perfect!” Joe swore again.

He wondered how she would take such a blow. Joe lamented how much she had gone through since their move from home. They both lost friends, community, family connections, and the knowledge of how they fit into the grand scheme. He couldn’t return with only bad news.

Maybe I can still catch the OIHO before they close, get a new job next week, and everything will be just like before.

He paused to wonder if being just like before was anything to strive for.

4LA GUERRE BUREAUCRATIQUE

Wheeling the rusted hulk around, Joe sped toward the long line that awaited him. Arriving at 12:45 p.m., horror filled his heart when he saw the slinking centipede of humanity stretching out the door and around the block. They would close the doors at three. Halting service was the only thing the OIHO did precisely. He made eye contact with one of the men in line who widened his eyes and shook his head at Joe as if to say, “You’re totally screwed.”

As Joe searched for a place to park, he caught a glimpse of the Inclusion Banner flying atop the OIHO building. It was a grotesque piece of cloth gesticulating high in the breeze. Colors of the rainbow and a myriad of melanated skin tones intermingled in an unrecognizable desecration. One skin color was conspicuously missing from the banner just as American flags were notably absent from the building. The brutalist architecture of the OIHO signaled its domination and spiteful character to the serfs it consumed through its mandible-like doors. The building was first constructed as a public library several decades ago, evolved to an impromptu druggie camp during a period of urban decline, and finally ended up as a reliable producer of homelessness in its role as the OIHO. The surrounding buildings in the downtown area all followed similar arcs of usefulness, disuse, then malicious use. Any name placards from the original constructions were invariably scuffed, painted over, or crudely replaced along with any statuary. These modifications occurred in the repeated waves of iconoclasm that had become the national pastime.

He circled the block looking for a parking spot and wasted an additional fifteen minutes. The clock on his dashboard, always three minutes behind, blinked unsympathetically at him the same way a forest animal observes some stranded traveler starving to death in the wilderness. Greasy with sweat, Joe leapt from the car and ran toward the line. Breathing heavily, he slowed to a walk as he joined the throng. Three more filed in behind him minutes later. The wind rustled the palm tree next to him but refused to stoop to his level and cool his sweating body.

An OIHO employee sullenly patrolled the queue with a clipboard and the precious orange card that read, “Line Cutoff.” She was counting the number of people out loud in an inhuman mumble.

“Seventy-eight, seventy-nine, eighty, eighty-one. . . .”

A homeless man sauntered on the sidewalk across the intersection from the OIHO building. He unfolded his chair and pulled a plastic bag from his satchel. It was popcorn.

“Ninety-four, ninety-five, ninety-six.” She paused to look at her clipboard.

Struggling to make the wires in her brain connect, her pen made furious calculations. The employee gave a dead stare at the paper for a minute then pulled the orange card and handed it to number ninety-six.

“OK, listen up!” her voice leaked with false legitimacy. “This card is the line cutoff. They’re prolly not gonna see you before closing after that. You can still try and wait in line, but prolly not gonna happen.”

The man she handed the card to looked up at the sky and breathed deeply. Joe was four spaces behind him. No one budged.

“I can make it,” the woman behind him reassured herself.

Joe concurred and decided that there was nothing to lose at this point. An hour passed in the smothering heat. The brewing magma of his scream in the car subsided as he settled into a dim acceptance. Looking up at the cruel sun, he felt another heat source to his right. Fear coursed through his frazzled nerves. Something pulled his eyes toward his reflection in the glass window. Joe resisted this urge out of terror but ultimately succumbed to the magnetic draw. With a shudder, he realized a profound change in the familiar face he was used to seeing in the mirror.

Joe gazed into the darkened, distorted form, and it gazed back into him. A deep stillness enveloped the pair: a man and his reflection. The world around them faded, and the noisy street quieted to a profound, supernatural silence. For a moment, there was nothing at all besides the transfixing tendrils of shocked disquiet. It was the first time Joe had an inkling of the supernatural. He had looked in the mirror numerous times before but had only seen the tamed, supine image of himself. Now, on this baking city sidewalk, a coup occurred on the other side of the glass. Through the crack in his exterior pioneered by the frustrated screams of rebellion, a new impression appeared before his eyes, ravenously pursuing him into the deepest recesses of his heart with accusations and judgments. Joe always knew these condemnations were there but smothered them to keep the peace. They maintained their standoff until inexplicable dread wrested Joe’s eyes from the terrible and damning gaze.

Joe shivered for a moment after his encounter. His heart pounded in his chest as if someone was trying to kill him. He closed his eyes and put his hands on his knees.

It’s fine, Joe, he thought to himself, it’s just your reflection.

He took a peek at the window to confirm this assessment only to quickly avert his eyes. Straightening up, Joe could see the door inside now and held on to hope.

More time passed, and it was now only twenty minutes from closing. He at least was getting clouds of conditioned air sortieing from the door. The temporary comfort of the cool air failed to assuage the anxiety he felt over what he saw in the window’s reflection. Resolving to forget the encounter, Joe decided that it was merely an episode of fatigue. The same employee who bestowed the orange card waited at the entrance with keys and a watch. As the previous cardholder crossed the threshold, she grabbed it from him and walked along the line. Making her assessment, she gave the card to Joe.

“Okay, they’ve been moving pretty quick, but no promises getting in. I lock the door at three o’clock,” she bellowed to the assembly.

A sailor whose ship is sunk clings to any wreckage that passes by. Joe clung to the card adrift in the sea of his own thoughts. Turning behind him, he saw at least fifty more desperate souls. Joe looked at the fateful pane of glass further down the line. It was at an oblique angle, and the reflection was no longer visible. A few despondent individuals slunk away from the end of the line. The homeless man chuckled and heckled them as they abandoned hope.

“Hey, I’ll save a spot on the sidewalk for ya! Oh, and you! Oh boy, you just wait until you hit the streets. You can work at the corner of 8th Street with the other denials! I’ll be your first customer.”

Joe finally entered the building and took ticket number 612. Two more made it in behind him before the doors were locked shut. He couldn’t bear to look back at those who were turned away.

“We open back up on Monday at 9:30.”

Joe knew that coming back on Monday would be useless.

After a sustained period of waiting, a voice called out, “Number 612, now calling number 612.”

He leapt up from his chair to engage in the necessary charade. “Hi, I need to–”

The employee angrily interrupted, “Stand behind the red line.”

“Okay. . . .” Joe had no choice but to kowtow.

“How can I help you?” The lump was satisfied with Joe’s obligatory gesture of submission.

He took a deep breath. “Yes, I need to renew my housing certification.”

The dead-eyed troglodyte pursed her lips. “Kay, give me your paperwork.”

Joe looked on with furrowed brow as she shuffled through the papers.

“Looks good; now I just need to see your interview sheet.”

His soul crumpled like a grounded submarine. “Interview sheet?”

“Did you check in with Mr. Smith before coming in today?” The employee kept her eyes glued on the papers.

“No?” Joe’s toes pressed firmly against the red line.

She collected the papers and handed them back. “You need an interview checklist from Mr. Smith before I can help you.”

Undeterred, he fired back at the risk of eliciting the employee’s “fight or obstinance” response. “I didn’t have to do that last year.”

The employee perceived the resistance and opted to both fight and be obstinate. “Well, you should have. Who did your paperwork?”

Joe crumpled one of the papers slightly in his hand. “I have no idea.”

“Did you read the information packet on how to submit your package?” She directed the crushing weight of the administrative state against him.

Pivoting on his feet, he prepared his parry. “Yes, I checked online before I came in, and it didn’t say anything about an interview sheet.”

The employee settled in for the killing blow: “I have the instructions right here. Look at this. You see this? Right there. In-ter-view sheet. You see it?”

“Yes, I see it, but the packet I read didn’t. . . .” Thoroughly pinned, all Joe could do was watch the disaster unfold.

“Where’d you find it?” she prodded him again.

Unsure of the angle, Joe countered, “It was right on your website.”

“Which website?”

His pulse rose with disgust. “The OIHO website.”

She rolled her eyes. “Which one?”

“Is there more than one?” Joe asked incredulously.

The employee continued, “IT services made a new website for us two months ago.”

Digging his hole further, he objected: “What’s the URL? I just searched ‘Office for Inclusive Housing Opportunities’ and I clicked on the first one that came up.”

One of the other “inequitables” in the stall next to him gave him a look as if to say, “Shut up or it’ll get worse for you.”

In a droning monotone, the employee laid out Joe’s critical errors: “You’re going to get the old one that way. You should have used the new one. You’re like the hundredth person I’ve had to tell.”

Joe’s anger got the best of him. “Why wasn’t it posted somewhere that the website was obsolete?”

“Because we don’t use it anymore,” she said with narrowed eyes.

He raised his voice: “Then how are we supposed to know?!”

The employee decided she had enough. “Stop arguing with me. You need the interview sheet from Mr. Smith.”

“Fine, where is he?” Joe put his hands in his pockets and clawed at his legs in frustration.

In a self-righteous declaration of victory, the lump replied, “His office hours are from 12 p.m. to 3 p.m., Monday through Friday.”

“Is his office in this building?”

“Yes.” Her tone indicated she was finished with him.

Joe clung to this new hope. “Where?”

“He probably left already,” the employee swatted him down.

Undeterred, he fought on: “Well I can still give it a shot.”

Reluctantly, she directed him down the hall to the second door on the right. After grinding his teeth on the walk over, Joe knocked on the door that bore Mr. Smith’s name placard.

“Come on in.” A smooth, Louisiana drawl seeped through the door frame.

Joe entered the office with trepidation but relief that he was still in his office. A dark-complexioned man with gold-rimmed glasses sat clacking away on his keyboard.

“Hey, Mr. Smith, sorry to bother you. The lady at the counter said I need to do an interview sheet before I can get my housing voucher.” Joe wiped away the sweat from his forehead.

“Absolutely,” Mr. Smith replied as he pulled a form from his cabinet. “Okay, you’ll need to get these signatures, and then you can contact me to set up your interview. It’s just run-of-the-mill stuff about your background.”

Joe looked in dismay at the list of five names with various titles and the diverse demographic qualities he would need to gain their signatures. He saw a thin stack of completed signature sheets on the corner of Mr. Smith’s desk. The signatures were mostly unintelligible scribbles apart from a rather distinctive set of loops under the name “Laura Berg” in deep purple ink.

“Are they all in this building?” he quivered.

“Perez and Greene are. Jiminez is at city hall, and so is Darron. You’ll need to make an appointment with Berg. She teleworks most of the time and usually only comes in Wednesday afternoons.”

Joe stood there dumbfounded. It would take at least a week to track down all of the signatures, not to mention the interview itself. All he could do was let out a pathetic, “Okay.”

He slowly made his way out of the building, empty handed except for the sweat-stained signature sheet. The sun beat cruelly on him as he returned to his car. Sweat and tears mixed freely on Joe’s face.

The homeless man yelled after him, “Everybody gets screwed, buddy! Everybody!”

5FORGING AHEAD

Joe sat in his car and relinquished his eyes to the rearview mirror with a tilt of his head. He saw haggard, green eyes set against a prematurely furrowed brow. The imprecatory stare accosted Joe’s helplessness. On the other side of that mirror were desires free from restraint, an unabashed, white-hot metal untainted with the base ore of meek compliance. But after all, it was just a reflection. There was no OIHO on that side. There was no outsourcing or Mumbai. There was no alienation, atomization, or rotted heartland.

Joe broke the stare and checked his phone. He had a single text from his wife.

“Babe?? What was that call? Are you okay? You have me super worried.”

He could only muster the text, “I’m on my way home.”

The drive home was a blur for Joe. Whether he had close calls or ran red lights, he had no idea. He pulled into the cracked, weed-strewn driveway in front of his little bungalow. The drainage ditch in the driveway’s entrance jiggled the car’s sinewy suspension. Settling into his spot, Joe turned the engine off and sat dead-eyed. There was a light on, and he could just make out the ghostly outline of Jill’s shadow on the window shade. Her slender, feminine figure sat with great concern in the recliner. Joe received one more caustic glance from the mirror, then entered the small brickwork house.

“Babe, what is going on? Why are you drenched in sweat?” In a suppressed tone she asked, “Were you mugged?”

“No, I wasn’t mugged.”

“Well, what happened?”

Joe collapsed like a used tissue on the leatherette couch. “What didn’t happen today. . . .”

“I’m sorry, baby. Bad day at work?”

“You could say that.” Joe put his head in his hands and stared at the faux Persian rug.

“That Mr. Raab is such a joke. I hate that he–”

Joe interrupted Jill’s obligatory invocations against Mr. Raab. “I got let go today. Outsourcing. They put up a list in the breakroom of who was and wasn’t keeping their job. They even laid off Tyler. Most of the office’s work is going to Mumbai.”

Jill’s face turned from sympathy to dread. “Oh my gosh . . . Joe! How are we going to pay rent? I can’t support us on my salary. We’ll barely have enough for groceries!” Tears started forming in her eyes.

“Don’t worry about the rent.” Joe let out a depressed chuckle.

“What? Did something happen with the OIHO?” Jill quivered like a sapling in a strong wind.

Joe remained silent.

Her voice trembled as she repeated her question in a low whisper: “Did something happen with the OIHO?”

Her husband began slowly, “It’s not denied per se. Just basically impossible to get done. They changed the rules this year and didn’t tell anyone.” He let the frustration flow freely. “I have to get five signatures from all over town and then schedule an interview. I’d basically be wasting my time at this point. All applications after Friday usually get denied anyway.”

“Oh, Joe. . . .” Jill began sobbing uncontrollably. She feared living in the government housing that would remain their only option without a housing endorsement. “Tessa texts me every day with the horror stories. They found their daughter playing with a dirty needle, and they got in trouble for even reporting it!”

Joe reflected for a moment on Tessa and Jake. They were loose acquaintances who used to live one neighborhood over and go to the same church. They got denied last year due to their neighborhood reaching “equity capacity.” Joe remembered feelings of bleak detachment toward their plight.

“I mean, I can still do all the stuff and send it in and maybe there’s a chance,” Joe lied.

Jill interjected, “I can’t live over there. I can’t. I can’t! How am I supposed to live over there when Whit—” she censored herself, “women who look like me can’t even leave the apartment alone even in the middle of the day?”

“It’s not over yet,” he injected some false optimism.

“No, it’s over. It’s so over. Joe. . . .” she looked up at Joe with crystalline blue eyes adrift in the welling puddle of tears.

He returned the gaze and stared into her dark pupil.

“I’ll leave you if you don’t get our house back!” She lashed out, taking Joe by surprise.

“I could—” Joe barely mustered the next words. This wasn’t the first time she made this threat. “I could still do the appointments and get my paperwork in.” He made air quotes over the appointments.

“What do you mean?”

“I’ll have them signed off.” The words tumbled from his mouth as if he were regurgitating poison.

“You won’t have time?”

Joe lowered his tone. “I’ll have them signed.”

Jill gave a tortured whisper. “Are you going to fake the signatures?”

Her husband clenched his jaw. “All they’ll see is that I got it signed off.”

“Oh, and you’re just going to waltz in on Monday morning pretending you got all of that done over the weekend?” Jill chided.

“Look, it’s the only option we’ve got!”

“I can’t deal with this!” She pushed past him, grabbed her car keys, and slammed the door behind her.

Most of their frequent arguments ended this way. At this point, Joe was numb to the day’s cavalcade of disasters. Alone in his transient quarters in the setting sun, his eyes drifted around the cramped living room. On the mantle sat several certificates of meaningless achievement and appeasement. A vast television commanded the visual space of the room. It stood domineering and vacant as if a portal to incomprehensible horror. The couch faced this portal with its back neglecting the views from the window. Just as Joe spent countless hours of imprisonment to the screen in his cubicle, his evenings were spent in voluntary submission to the television. The muddled reflection in the opaque surface stirred existential dread. Joe’s sweaty hand drifted to the remote but his finger trembled on the power button.

Casting it aside, he left the house and walked a few miles to the nearest convenience store. Joe hadn’t smoked since college but felt compelled to buy a pack of his old favorites. Rushing outside, he drew a cigarette from its sheath and placed it in his mouth. The lighter’s flint made a brief flash in the darkness and gave way to a mellow flame. Joe took a long, cool drag. A warm breeze caused the palm trees to sway sympathetically.

The effect of the nicotine was instantaneous. After years of abstinence, his tolerance had returned to zero. The headrush heightened Joe’s senses and accelerated his thoughts to cruising speed. He exhaled the cloud into the light of an amber streetlamp. It took on a sallow complexion as it dissipated into the atmosphere, leaving no trace except Joe’s buzz. Looking up at the night sky, Joe spied the lights of a passenger plane flying high in the heavens. He wondered for a moment if anyone at all was looking back down at him.

“Anyone at all,” he repeated his thoughts aloud.

Looking across the street, the Windview Motel flashed its neon vacancy signs. The building’s paint was a sickly and faded blue with two decks of rooms. In decades past, it hosted the throngs of prospective hopefuls traveling west to forage a new dream from the sunny sands of the Pacific. Now its parking lot bore multiple tents, marking the presence of a homeless camp. A single figure, the manager of the motel, stood as a black silhouette on the balcony in front of the main office. He lorded on his podium looking down grimly at his petty fiefdom. The urchins subsisting on his land paid him in food, drugs, sex, or whatever else he deemed a good price for not calling the police to evict them from the lot. With the OIHO denying more and more vouchers, business was booming for these extortion farms.

Even in the night, he sensed the manager’s hungry eyes drift toward him like the searchlight of a prison camp. Joe used to drive by Windview on his way to work. As the pool of societal refuse piled up in the parking lot, he changed his route to avoid the negative stimuli. Nevertheless, Windview haunted him like a specter, shadowing his every move and promising to swallow him whole if he slipped. Its mouth hung agape as the manager’s silhouette burned itself into Joe’s eyes. Unsettled, he finished the cigarette in a few minutes and threw the butt into his reflection in a stagnant puddle. He gave the remainder of the pack to a homeless man on his way home.

Joe awoke the next morning shortly before noon. He was alone in his bed, but he could see Jill’s car in the driveway. Sloughing off the covers like a scab, Joe checked the living room. She was on the couch cuddling a bottle of tequila. The housing paperwork still sat on the dining table. He gingerly took them over to the couch and sat on the floor next to her. Racking his frazzled memory to recall the signatures he saw on Mr. Smith’s desk, Joe practiced the signatures for about an hour. He took special care to replicate Berg’s with a purple pen he fortuitously found in Jill’s purse.

Was it two loops or three? Joe rubbed his face in trepidation.

He took the signature sheet in trembling hands and set it on the table. Moving the pens in succession as carefully as two aircrafts engage in aerial refueling, Joe forged five signatures.

6MONDAY

After a silent and despondent weekend, Joe snuck out of the house to submit his felonious paperwork after Jill left for work. He kept Mr. Smith’s signature line blank with the hopes of getting at least some form of legitimacy for his papers. He wore an old baseball cap and a surgical mask so that his interviewer wouldn't recognize him as the desperate, sweaty, and nameless individual he turned away last Friday. Arriving at the OIHO office, Joe breezed past the line. When the employee at the entrance questioned him, he merely notified them of his appointment with Mr. Smith. To his surprise, they didn’t ask for any verification. Joe was immediately suspicious of his ease of entry but mused that perhaps his luck was turning. He knocked on the door.

“Come in.”

“Good morning, Mr. Smith. I have my interview sheet signed off,” Joe lied through his mask.

The bureaucrat nodded and turned toward him. “What’s your name?”

“Joseph Blaine.”

Despite his disguise, he had to have his real name on the paperwork, lest his efforts be for nothing.

“Hmm, I don’t see you listed for an appointment. Well, I do have a no-show, so we can do this real quick.” Mr. Smith seemed to not recognize him at all.

“Great.” Joe was far more thankful and relieved than he let on.

“Let’s take a look at your sheet. Okay, so Ms. Berg explained what to expect in the interview?” The bureaucrat peered over his golden glasses.

“Yeah.” Joe wondered what critical information he would be lacking.

“I’m honestly surprised she signed you off. She has a pretty strict adherence to equity quotas and usually won’t send . . . guys like you . . . to the interview at this stage in the game,” Mr. Smith questioned.

Bemused, Joe confirmed to himself that the process was designed to be essentially impossible. He replied, “I’m not sure, but I’m happy to be here.”

“Okay, I’m going to ask you a series of questions about your background after you sign this waiver.”

The waiver sat arrogantly on the desk. It proclaimed a series of demands to release his demographic information, consent to periodic home searches, and consent to be electronically recorded. Rounding out the form was a list of executive orders shoring up its wobbly legitimacy along with the Equity and Inclusion Act. Joe signed the paper and quietly resented the tyranny of forced consent. He signed the same form last year.

“Thank you very much. Alright, let’s get started with the interview.” Mr. Smith pulled up the questionnaire on his computer.

Preparing to do battle with the administrative state once more, Joe settled into the chair in front of the desk. At this point, he noticed that it was considerably shorter than his opponent’s.

Mr. Smith began the first volley, “State your name for the record and your current address.”

“Joseph Arthur Blaine, 642 Floyd Avenue.”

Keeping his eyes on the computer screen, his interrogator asked, “Are you applying for the same address?”

Joe replied meekly, “Yes, that’s correct.”

“Alright, I’ll skip to question 12. Have you been approved for a housing endorsement before?” Smith’s dark eyes scrambled across the questionnaire.

Knowing previous approval had a large impact on future applications, Joe felt relief that he could positively confirm.

Turning to face the applicant after the opening skirmish, the real battle began. “Okay, let’s get to the important stuff. Age, height, and weight?”

His adrenaline-soaked mind swirled to keep up. “Twenty-five, five foot eleven, 170 lbs.”

Making some entries into his sheet, Mr. Smith asked the next questions with a wince as if he knew Joe had all the wrong answers.

“Race?”

“White,” the applicant said sheepishly with a twinge of conditioned shame.

“Ethnicity?”

While Joe’s ethnic makeup was a mix of various European countries, he knew the question was only asking if he was Hispanic or not, to which he answered, “No.”