Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Atlantic Books

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

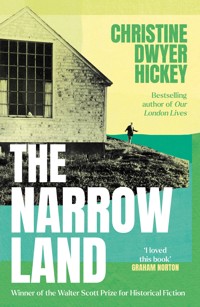

WINNER OF THE WALTER SCOTT HISTORICAL PRIZE FOR FICTION, 2020 WINNER OF THE DALKEY LITERARY AWARD FOR NOVEL OF THE YEAR, 2020 SHORTLISTED FOR THE IRISH BOOK AWARDS, 2019 An Irish Independent and Irish Times Book of the Year, 2019 From the author of Tatty, the Dublin: One City One Book 2020 choice ________________________ 'It is a long time since I have read such a fine novel or one that I have enjoyed quite so much.' Irish Times 1950: late summer season on Cape Cod. Michael, a ten-year-old boy, is spending the summer with Richie and his glamorous but troubled mother. Left to their own devices, the boys meet a couple living nearby - the artists Jo and Edward Hopper - and an unlikely friendship is forged. She, volatile, passionate and often irrational, suffers bouts of obsessive sexual jealousy. He, withdrawn and unwell, depressed by his inability to work, becomes besotted by Richie's frail and beautiful Aunt Katherine who has not long to live - an infatuation he shares with young Michael. A novel of loneliness and regret, the legacy of World War II and the ever-changing concept of the American Dream. 'A brilliant portrait... With a beguiling grace and a deceptive simplicity, Christine Dwyer Hickey reminds us that the past is never far away - rather, it constantly surrounds us, suspends us, haunts us.' Colum McCann

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 675

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

THE NARROW LAND

Also by Christine Dwyer Hickey

The Lives of Women

Snow Angels

The House on Parkgate Street and Other Dublin Stories

Cold Eye of Heaven

Last Train from Liguria

Tatty

The Gatemaker (The Dublin Trilogy 3)

The Gambler (The Dublin Trilogy 2)

The Dancer (The Dublin Trilogy 1)

First published in hardback in Great Britain in 2019by Atlantic Books, an imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd.

Copyright © Christine Dwyer Hickey, 2019

The moral right of Christine Dwyer Hickey to be identifiedas the author of this work has been asserted by her in accordancewith the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may bereproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any formor by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording,or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyrightowner and the above publisher of this book.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names,characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’simagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead,events or localities, is entirely coincidental.

Every effort has been made to trace or contact all copyright holders.The publishers will be pleased to make good any omissions or rectifyany mistakes brought to their attention at the earliest opportunity.

2 4 6 8 10 9 7 5 3 1

A CIP catalogue record for this book is availablefrom the British Library.

Hardback ISBN: 978 1 78649 671 3Trade paperback ISBN: 978 1 78649 672 0E-book ISBN: 978 1 78649 673 7

Printed in Great Britain

Atlantic BooksAn Imprint of Atlantic Books LtdOrmond House26–27 Boswell StreetLondonWC1N 3JZ

www.atlantic-books.co.uk

To A.C. and J.M.,who left us in the dead of winter

Contents

The Bringer of War

Mrs Aitch

Venus

Mercury

The Bringer of Jollity

Die Trümmerfrauen

Cape Cod Morning

‘Every man has within himself the entire human condition.’

MICHEL DE MONTAIGNE

The Bringer of War

1

AT THE TOP of the terminal steps the boy stops short and the woman pulling him along pulls harder. The boy resists, this time bending at the knee and pressing his weight down into his heels. The woman waits a second and then spins around.

‘What? What is it now? What now?’

As she turns, her basket swipes the side of the boy’s bare leg. A long red scratch springs out on his skin. The leg flinches, but the boy doesn’t make a sound. He looks at the leg, he looks at the basket then he looks at her. He leans to the side and allows his suitcase to slip out of his hand.

‘I’m not going…’ he begins.

‘You’re not going? What do you mean you’re not going?’

‘I don’t like—’

‘You don’t like? What, now, don’t you like?’

This is not the first time they’ve stood in this place having this argument. The last time was two summers ago, the summer of 1948, when she’d turned her back on him to go buy the tickets and he bolted, leaving the shiny brown suitcase Harry had bought him sitting there in the middle of Grand Central. He didn’t get very far then. He hadn’t got the sense to try for an exit and was still too scared of elevators and escalators and anything, in fact, that moved him towards something he didn’t already know or couldn’t already see. And so he just plunged into the crowd and began scooting from side to side. It took no time at all between her reporting the matter and the cop dragging him back to where she’d been waiting, under the clock with four faces.

‘You the mother?’ the cop had asked.

And she’d nodded yes, because she just couldn’t bring herself to go into the whole sorry story, and to have to do it too against a blubber of tears.

She had shown her temper back then, smacking the boy on the side of his head – the first and only time she had ever done that. And then shredding the tickets in her hands and flinging the lot in his face, she had yelled, ‘Happy now? Happy?’ with the cop still standing there listening to her. ‘Is that what you want? I take a whole day off work just to go with you on a train to Boston. A whole day, just to come all the way back on my own, and this is how you treat me. Well, you can go boil for the rest of the summer in the apartment, go boil like a piece of meat in a pot – you hear me now? You can just go…’

The boy didn’t budge. He never even raised his hand to comfort his slapped ear. A slight sulk on his face was all: no shame, no regret, nothing to show any real upset. Just stood there, peering straight through her, like he was trying to figure out what colour wallpaper was inside her head.

And here they are again, two years gone by and the boy now ten years old, so far as anybody knows. The case Harry bought him is back on duty, a little more faded and a lot more scuffed after two years of getting dragged in and out from under his bed, where it had been acting as a secret container for his comic books and bits of paper and God knows what other peculiarities he kept hidden in there.

This time, she is taking no chances. The ticket was bought during yesterday’s lunchbreak and a porter Harry knows on the New Haven line has promised to keep lookout in case the boy gets any ideas about jumping off at the next station. It has all been arranged. She will put him on the train, take note of the car number and, when she sees the train pull out of the station, go call Harry in work who, in turn, will call Mrs Kaplan to let her know there have been no complications. When the train pulls into Boston, Mrs Kaplan will board it and they will continue together on to the Cape. After the train, there will be one of those chubby buses, after that an automobile. And then the sea, the sand and Mrs Kaplan’s grandson named Richie.

She is tired of telling all this to the boy: the bus, the automobile, the sea, the sand, the grandson named Richie. A dog even! Tired building it all up while the boy, in his silence, pulls it right back down again.

But he promised Harry; he swore it – this time there would be no monkey business. He had seemed sincere in his promise too. Harry even made a few jokes about him running off last time and having to be brought back by a cop. He said it had been on the radio news – the whole of New York had heard about it. The boy sort of grinned when Harry said that, a nice-looking boy, too, when he bothers to smile. The past two years have made such a difference to him: better at school, better at eye contact and, when you can get him to talk, he speaks like any other American boy, practically. He takes more of an interest, too, and she’d been so long telling him, ‘Sweetheart, you got to take more of an interest in life.’

She has every confidence that this time he will act like a big boy. She said so a few days ago to Harry who, through the mirror, had cocked one eye at her over his foamed-up face. Every confidence.

She lays the basket down next to the suitcase. ‘I asked you a question,’ she says.

The boy ignores her.

‘What’s the matter with you – answer me, please?’

But the boy still refuses to say a word. And so she starts on him. She starts off slow and steady but soon she is letting him have it in shovelfuls. She lets him have it for all the trouble he’s been these past two summers when she’s had to pay, yes, pay, a sitter so she can go out to work while he mopes around the apartment cutting dumb little paper figures out of magazines and playing those dumb little games that he plays with them. She lets him have it over Mrs Kaplan – Mrs Kaplan who has been so kind as to allow him another chance after all the inconvenience two years before. Mrs Kaplan of all people. The woman without whom he would be God knows where, dead at the side of a road in the middle of Europe somewhere. Mrs Kaplan, the woman who had probably put the whole idea in President Truman’s head in the first place about saving all those orphans. Anything that comes to mind, she throws at him: his stealing food from the kitchen as if she never feeds him or would refuse him a bite to eat! His wandering around the building in the middle of the night, spooking the neighbours! And as for all those lies that come pouring out of his mouth. Senseless lies! To his teachers; his classmates; the man in the grocery store – to any ear with a hole in it that is willing to listen.

She wants to stop. To pause, anyhow, and think about this barrage of words. But just like it happens sometimes in the typing pool, the words seem to shoot out of their own accord except now they’re landing on the boy instead of on the page. And NO, she continues, she won’t be tearing up the ticket like before, if that’s what he’s hoping. He will get on that train and she will go back to work. He will get on that train and do as she says and she will be standing on the platform until she sees the train disappear down, right down, the track.

‘I don’t like…’ he says and then, ‘I don’t want…’

‘And I don’t care! You hear me? I don’t care what you like or don’t like, what you want or don’t want. You understand? I’ve had enough of all your likes and your dislikes… of your— wants and your don’t-wants. And you know what else? I’m tired. Tired because you kept me awake all night, in and out of the bathroom, light on, light off in the hallway. I’m tired and—’

The boy lowers his head, then swallows. ‘Please, Frau Aunt,’ he finally says.

She turns away from him. On the concourse below, she watches the crowd dissolve into one big moving mass with umbrellas, hats, purses, suitcases tacked onto it. For the first time, she notices how many soldiers and marines are moving around down there. It’s as if the war in Europe is still on. Yet the servicemen seem different somehow, younger and more perked up than before. She remembers then: they’ve moved on to a new war now, and what she’s looking at here is a whole batch of brand new men. She puts her hand in the pocket of her raincoat and pulls out a handkerchief, blows her nose and puts the handkerchief back in. She lifts her face and looks up to the vaulted ceiling and the arched windows beneath it that have taken the rainy, grey daylight and turned it to silver. It makes her think of a church from her childhood. A church she can no longer name where a once familiar service was going on over her head, and at eye level, the elbow of a father on one side and on the other the elbow of a mother. She feels ashamed of herself then for yelling at the boy, for sending him away when he doesn’t want to go. For bringing all that up about his private little world, the games that he plays when he goes there. He is, after all, still a child, and as Harry often says, ‘God knows what that kid’s seen in his time.’

She comes back to the boy, softened. ‘Look,’ she begins, ‘you’re a good boy. I know that. But it’s been tough, you know? And not just for you but for me too. I try. I do try. But now you need to have time away. Time for you. Time for me – you understand? We’ll get along better that way when you get back. A new start we’ll have then. New home, new school, new… well, a whole new life, you could say.’

‘But I won’t know where the apartment is. What it looks like or nothin’.’

‘As soon as Harry finds it, I’ll write and tell you all about it.’

‘And school – how am I supposed to find that? I’ll be starting back late, everyone lookin’ at me when I walk in the door.’

‘Nobody cares about any of that. Other boys start late – those harvest boys, they don’t come back till maybe the end of October. You’ll be back by the end of September. And you may not even have to change schools, not if Harry finds some place close by.’

The boy keeps shaking his head in that way he has – like it’s loose on his neck. She wishes he would stop doing that.

‘Look, if you want,’ she says, ‘I can do what I was supposed to do last time – you know, go with you as far as Boston, and when Mrs Kaplan gets on I’ll get off and come straight back. It’ll cost more money and I’ll get in trouble in work. But I’ll do it. If that’s what you want.’

‘It’s okay,’ he says, so quiet she only knows he’s said it at all because she reads the shapes of the words on his lips.

‘It’s just a few weeks, sweetheart. A few weeks goes by so quick you won’t hardly notice. And you’ll have a friend to play with. And the dog, don’t forget – I don’t know what sort but I bet it’s a beauty. You’re a very lucky boy. You should know that. A nice big house and garden. A beach of sand. A sea to swim in. And air… think of it – all that fresh air!’

‘I don’t like fresh air,’ the boy says. ‘I don’t like the boy, I don’t like the beach.’

‘You don’t know the boy! And you’ve probably never even been to a beach.’

‘Harry said he’d take me to Coney Island, but he never did,’ he snaps.

‘He will. He said he will and he will. But let me tell you, it’s not so great, that Coney Island, noisy and dirty and the crowds… But where you’re going? This is paradise I’m talking about here.’

She brings her face a little closer to his and cuffs her hands around the tops of his arms.

‘Are you afraid – is that it? What are you afraid of then? Won’t you tell me? Is it all these soldiers? They’re going off to the other side of the world, to a place called Korea. It’s not like before, you know.’

The boy begins shaking his head again.

‘Is it the tunnel then?’ she asks. ‘Is that it? Does it make you think of the air raids? I promise you there’s nothing in those tunnels but railroad tracks and trains. That’s all over now. That’s all in the past. This is America. You’re safe here, sweetheart. Safe.’

She waits for the boy to give her something but he won’t even look at her now.

‘How can I know how you feel if you never tell me anything. How?’

He pulls back for a second then turns on her suddenly and screams in her face. ‘I said okay – didn’t I? I said I was going – didn’t I? How many times you want me to say it? I’m going. I’m going!’

The way he just blasts it out. Right in her face.

‘Don’t you go yelling at me,’ she begins, ‘don’t think you can just—’

But the boy isn’t listening; he is too busy counting the buttons on her coat. Down and then up again.

‘Stop doing that,’ she says. ‘Will you please stop? Counting things, it drives me crazy the way you— the way you…’

She takes her hands away from his arms, picks up the basket, settles it on her arm. Then she picks up his case and clamps it to his chest. Her throat feels tight and sore now; she has to push her voice to make it go through.

‘And another thing, don’t call me Frau Aunt again,’ she says. ‘I’m tired telling you. We don’t speak German in this country – you got that?’

She pulls him by the sleeve of his jacket, down the steps and towards the track. When they reach the barrier, they get in line and she begins rummaging in her purse and at the same time pulling herself together.

‘Look, I don’t think we should leave it on a sour note,’ she says. ‘I don’t think either of us wants that.’

She edges his ticket out of her pocketbook. ‘Did you write a letter back to that boy Richie? Did you write back like I told you?’

The boy turns his head to the side, as if she’s not there.

‘I’m asking you a question now, if you could answer me, please?’

‘I wrote a letter,’ he mumbles.

She combs her fingers through his hair and he shakes her hand away.

‘Good,’ she says, ‘because, you know, it would not be very polite if you didn’t write back. It would be impolite is what I mean to say.’

On the train, she lifts his case onto the overhead rack and says, ‘Mrs Kaplan will lift it down for you when you get there.’

She waits for him to take offence, to let her know ‘I’m tall enough – I can take it down myself.’

But he says nothing. She puts the basket down on the seat. ‘Now remember, don’t you take your eye off that basket. Someone needs the space, you put it on your lap. Or lay it on the floor under your feet. Understand? And later, when you’re all settled in, you give it to her, you say, “This is for you, Mrs Kaplan, to thank you for having me to stay” – you got that now? And be sure you let her know I made the apple pie myself but that I bought the strawberry one in the French bakery on Fifth Avenue. Well, I guess she’ll see the name on the wrapper when she opens the box – everyone’s heard of a place like that.’

The boy stands stiffly by the seat, his legs like two white stalks growing out of his canvas shoes and up the legs of his short pants. Away from the apartment, he seems so tall. Even with her propped up on high heels, they are almost on a level. Soon he will pass her out. After that, he will pass Harry out. When he first came to live with them, she thought he would never grow tall enough or flesh out enough to be able to fit into poor Jake’s clothes. He’d been so small for his age then. But now? Look at him. Five minutes’ wear was all he got out of Jake’s clothes before she had to give them away to strangers. Too tall and still too thin, like she never feeds him.

She hands him a comic book, a candy bar and a bottle of soda. She gives him an envelope with coins and five dollars inside. She tells him he needs to make it last for six weeks but that he should buy ice-cream for his new friend, Richie, or maybe take him to the movies or something.

‘Be polite at all times – thank you, please, all that. And call her ma’am, unless she tells you different. She will. She’s a very nice, down-to-earth lady – you know, for a lady. But just to show you know how to be polite. And remember, Richie’s mom is also called Mrs Kaplan on account she was married to Mrs Kaplan’s son. Say your prayers. No grabbing for things at the table. And eat nice. And, please, no lies. If you don’t know something, you don’t know. You don’t have to make up an answer. You understand? Good. Because, you know, nobody likes a liar. Not even another liar.’

The boy sits down on the edge of the seat, the comic book over his lap and the candy bar and soda resting on top of it.

‘You look tired,’ she says. ‘Did you sleep even one wink the whole night? You can sleep on the journey, you got a few hours – just take good care of that basket, okay?’

The boy nods.

‘Well, that’s it, I guess,’ she says, ‘and don’t forget to send me a postcard. Or a letter, maybe. I love to look at your handwriting – you know that, so grown up that handwriting. It’s only a few weeks but, still, it’d be nice to hear from you.’

The boy won’t look at her. He folds the envelope of money and puts it into his pocket. He takes the basket from the seat and lays it on the floor under his feet. Then he turns his attention to the comic book.

She leans down, kisses the top of his head and lowers her voice. ‘And no speaking German, huh? It’s better, I told you. I’m not saying there’s anything wrong with German – what is it but another language, after all? But, you know, it’s just better you don’t speak it, is all.’

His face is flushed and she can see now that his bottom lip has tightened downwards, like maybe he is about to cry. Something inside her wants him to cry, to throw his arms around her and beg her not to send him away. She thinks, If he does that, I’ll keep him with me, I’ll hug him so tight he won’t know how to breathe. If he does that, I’ll know at least that he feels something for me. I’ll hug him and say it’s okay, honey, you can stay with me. You can stay forever and always and—

The boy shoves the comic back at her. ‘I read this already,’ he snarls.

She takes a step away. ‘Oh yeah? Well, give it to Richie then. Or throw it away – what do I care?’

On the platform, she stands under the window of his car, craning to see in. But all she can get is a glimpse of the crown of his head. Her shoes are biting into her feet and she feels like she could throw up any minute. It is taking forever for the whistle to sound, the wheels to give their first chug. All along the platform, she sees other people well placed to say their goodbyes. Faces raised to the train and a passenger hanging out the window of a car, or leaning over the opened window of a door between cars, talking, laughing, holding hands, crying even. A sailor and his girl taking a last, long chew of each other’s faces. She is the only one to stand alone. To have nobody on the other side of her farewell.

The boy is obstinate – she knows that – but still she hopes that before the train pulls away he’ll come round. Even a small wave, even a peek out the window. Oh, but he is obstinate to his bones. On the way here when she suggested they stop by the United Nations building – never mind that the rain had come on and they didn’t have all that much time to spare – he looked at her like she was dirt. A place she usually had to drag him away from. A place he loved. He had learned all about it in school, told them one evening at dinner in an unexpected outburst that had made her scared to blink in case the moment was broken. It was to be called the United Nations building, he announced, and the men inside would be in charge of the world so countries couldn’t just go round destroying each other any time they felt like it. Oh no, the men in charge would not allow any of that. And every country in the whole world would have its own flag blowing in the breeze outside, even Germany, because his teacher, she said that’s what it would be about, forgiving and maybe someday forgetting.

For weeks they’d been watching it grow out of nothing. He loved to look at the workmen crawl all over the concrete carcass, to count the empty sockets of the soon-to-be windows, take note of what had been added since last time round. It had become their thing, something they could do together, to go to the East River on her half-day from work and check on the progress of the United Nations building. And what did he do this morning when they got there but walk straight on by, leaving her trotting behind him all the way to 46th Street, where she’d had to make several grabs at his hand before finally she managed to catch hold of it.

A man comes into the car and begins to settle himself down opposite the boy. She watches the man push an odd-shaped case onto the rack, then fold his raincoat and bundle it on top. He sits down. She can see him take off his hat and smooth down his hair. He leans back and, bringing one hand to the window, begins tapping his fingers against the glass, nodding slightly as if he was listening to music inside his head.

The man catches her eye then looks away. The boy continues to ignore her. The man lights a cigarette and looks at her again. She feels her face grow hot. She begins to rub her stomach. The man will not associate her with the boy. He will assume she is looking in at him. He will think she is a crazy person who stands around looking in windows of trains. He will think she is one of those women who hang around terminals, picking up men for money.

THE BOY WATCHES Frau Aunt rubbing her stomach. He slides further down into the seat and now all he can see is the top of her head, her hand rising over it, once and then twice, like she’s some kind of swimmer.

Behind him the black tunnel is waiting. Soon Frau Aunt in her blue raincoat will be a blue stain and then a blue smudge and then nothing at all. It will be more than six weeks before he sees her again. Or – if this is a trick to get rid of him – it could be forever. Even so, he will not wave goodbye.

He thinks of the letter that Richie sent with the photograph wrapped up inside it, Harry laying it out on the table so the three of them could read it together. The writing on the letter had been like a five-year-old would do, but the words were all grown up (I do hope you enjoy… I’m very much looking forward to…). It was obvious that Mrs Kaplan had told her grandson what to write, even if Frau Aunt had said that she was sure they were Richie’s own words and that he was probably just advanced for his age on account of his going to private school. ‘And so what?’ Harry said. ‘They don’t teach them handwriting in those fancy schools?’

He just loved it when Harry said that.

The photograph had been of Richie: Richie and a ball on a beach. At the edge of the photograph was a corner of a rug and what looked like a dog’s two front paws lying on it.

He had not liked the look of the place. (And what sort of a name was that anyhow – Cape Cod? What was that even supposed to mean?) There was way too much sky behind Richie and a sea that looked like it was rising up just to bite down and swallow him up. He wished it would swallow him up because he didn’t much like the look of Richie either. He thought his face was a mean-looking face and that the smile on it was phoney. He had stared at the photograph for a long time; he came back to it again and again and stared at it some more. But he still hadn’t been able to find anything to like about Richie – not his hedgehog hair, not his striped T-shirt, not his mean, chubby face, not his bare foot pressing down on the ball and that look in his eye like it was a human head he was pressing into the sand and not just some old blow-up ball.

Richie is only part of the reason for being sore with Frau Aunt. Frau Aunt telling him to stop speaking German – that’s the other part. It was unfair and untrue of her to say that. He never speaks German now. As soon as he went to live with them, he started to work hard to unlearn the language. And she knows that, too, because she was the one to unteach him. She took all his own words out of his head and put new American ones in there instead. Hours of sitting at the kitchen table learning and unlearning till it grew dark outside, and now he has mostly forgotten how to speak it. Even when he does remember a conversation, it’s the meaning of the conversation he remembers and not the actual words that were used to make it. Hundreds of words he would have known how to speak when he came to America – some of them he maybe would have known how to read and even write down. Thousands maybe. Thousands and thousands of words and he’d really only held on to a couple of them and that was only as souvenirs.

*

The boy kicks the side of his foot lightly against the belly of the basket. He knows there is a special parcel at the bottom for Richie. When Frau Aunt tried to show him what she was putting in this parcel, he said he didn’t want to know. He closed his eyes and refused to look. But she went right on ahead and told him anyway: a colouring book and a box of paints, a kit for making a model boat or maybe it was a model aeroplane.

He lifts the basket from the floor. The lid opens like a mouth as he places it on his lap, breathing apples and cinnamon on his face. And something savoury – like garlic, maybe. The last thing to go into the basket had been the box Frau Aunt had bought from the French bakery. Tarte de fraises had been written on the tiny flag sticking out of it. A Frenchman sold it to her, wrapping it so gently in waxed paper and then laying it in the box like it was a new baby or something. And Frau Aunt smiling up at him and saying oh what a beautiful wax paper and oh what a wonderful tart and oh what a lovely box to lay it in and oh what a charming ribbon, and then complaining about the price as soon as they left the shop and calling the Frenchman a thief and keeping it up until she suddenly decided they should take a last look at the United Nations building. And he knew what that was called – rubbing salt into the wound was what.

The train begins to growl. Growl and shudder and gasp. He feels several movements within a bigger movement, strong and at the same time clumsy. A bull or a bronco horse struggling to break out of a wooden pen. The man seated opposite turns a page of his newspaper, gives it a little shake then takes another pull of his cigarette. He crosses one leg over the other. The hem of his pants lifts when he does that. Small black spikes on white skin. The man’s brown hat is on the seat next to him, a brown hat with a dip in the crown.

The boy knows the hat, knows that if you turned it upside down there’d be a printed crest on the stiff lining and that the lining would be stained with a greasy smear. He doesn’t know how he knows this hat – Harry only wears caps and only in winter. But it’s there anyhow, stuck to his memory, like all the other scraps of garbage that sometimes break loose and drift by.

Frau. That was one of the words he kept, though he didn’t really know why. Frau and otherwise mostly numbers because he couldn’t seem to forget how to count in German.

The train bucks. It gives a larger, more urgent gasp this time and the boy feels his knees slide forward. He stops them from falling further by digging his heels into the ground. Across the way, the man also lurches forward, cigarette smoke tumbling into the boy’s face. When it clears he sees that the man has long fingernails but only on one hand and that there are more of those black hairs showing under the cuff of his shirt and sprouting around his wrist-watch. The hairs seem alive to the boy, like tiny insects growing out of the man’s flesh. He hopes the man will keep his face behind the New York Times for the rest of the journey or, even better, that he gets off at the next station and takes his live-in colony of insects with him.

Outside the sound of whistles, one then another, then another again, slashing like swords against each other. The doors slap shut along the line. The boy hears his own heartbeat over them.

He lowers himself further down in the seat. Now, placing his hand on top of the cake box, he begins to push the ribbon until it falls over the shoulder of the box.

The train begins moving. Everything outside tightens up and slowly starts to retreat. He closes his eyes. He can see orange flickering through the skin of his eyelids. He feels his hands begin to shake. He can smell the strawberries from here, can already taste the unbearable sweetness of them curling into his throat and filling up his whole head. He makes a claw of his fingers and presses them into the soft, damp cushion of pastry and syrup and fruit.

Soon the tunnel will suck the train in, down, down into its long black gullet. Dead men will go floating by. Dead men and bits of old beds and drowning rats, struggling to stay alive. A woman stretched out with her face in the water. A fat man in a black overcoat who is swimming like a pig. If he keeps his eyes closed he will soon be asleep and will not need to see any of that. If he keeps his mouth full of pastry and strawberry, the sweetness will block it all out. Until the tunnel sets the train free again. Then the train and the man with the long nails and himself and all the people seated all over the train, or stumbling along car to car, will stop existing. They will be stuck between one place and another; they will be stuck until the train begins to spit them out, like pips, along the journey. When that happens, they can begin to exist all over again, but in some other place, a place they probably don’t even know yet.

HE THINKS HE IS on a different train as he begins to wake. A train in Germany just after the war. He feels jets of cool air on his face and thinks they are coming through the bullet holes left by the strafers in the roof. Or maybe through the spider-web cracks in the windows that have not yet been mended.

He reminds himself to keep his eyes shut. Because that’s what you do when you wake up among strangers in Germany: keep your eyes shut and pretend you haven’t yet woken or that you’re already dead. You do that until you’ve worked out what and who is around you.

He remembers those trains so well. Climbing on and jumping off again. Walking so long, walking and walking. Until the last train that took him to the big farm for making boys healthy again.

He imagines that he is on that last train now, sitting in a row of four or five boys. There is another row of bigger, older boys sitting across the table. He is the youngest of all the boys on the train, the youngest and smallest, and this is why they call him die Runt, or sometimes just Runt.

He is sitting on the end of the row by the aisle, where Frau Nurse can see him when he puts up his hand. Whenever he does this, the older boys elbow each other and snigger – ‘Oh, look,’ they say, ‘the runt has put his hand up again, he wants her to take out his little winky for him. Does it stick up when she does that – takes out your little winky?’

Three of the big boys playing cards. The fourth big boy stuck into the corner at the window. But the fourth big boy never looks out the window, not once. He doesn’t look at the cards or at the other boys, and when the drunk man stumbles into their carriage in a few moments’ time, he will not even look at him.

He does not know the name of the fourth big boy; he does not know the names of most of the boys. Not even the small ones sitting beside him. Apart from Otto a few rows back, he doesn’t know the names of any of the boys that have been placed here and there among the ordinary passengers. But he does know the names of two of the card players: Bruno and Erich. Because that’s something else you do when you find yourself among strangers in Germany – you learn, first, the names of the bullies.

The older boys will not allow the younger ones to play cards. Little boys are too stupid to understand cards, they say, little boys only spoil the game. But he understands the game all right. He understands it better, anyhow, than Erich who keeps making stupid mistakes and does not even know the difference in value between acorns and bells.

He knows the cards from watching the men play under the blue light. The blue light was in the big cave beneath the train station. What a stinky place that was. But there was another, even stinkier cave in the Tiergarten, next to the zoo, and that had a blue light too.

The big boys will not allow the small ones to touch the table and that’s not fair because they don’t own it. The table is stuck into the floor right in the middle and is supposed to be shared by both sides. Put one finger on this table, Erich has warned, and clip! We will chop it right off your hand.

When the boy turns around and kneels up on the seat, he can see all the way down to the back of the carriage and the other boys stuck here and there with their faces shy and also a little bored. Otto is squeezed in beside a big woman in a big brown fur coat. The woman is really a big brown bear who is wearing a blonde wig and red lipstick. He longs to tell Otto that so they can laugh till they ache. Otto is his friend. He knows him from the American camp where they both arrived on the same day but from different directions. They were put into the same section and then they became best friends. The big bear woman is fussing over Otto and stuffing him with cake. And there is Otto with his face turned to one side, trying to hide his greedy grin. On the far side of the aisle to Otto, Frau Nurse is reading her book with the English name on the front of it. Every now and then her face comes out of the book to check that her boys are behaving. My boys, she calls them, meine Jungs. Soon she will notice him kneeling up on the seat, and then her hand will start lifting and pressing back down – one, two, three times, bouncing a ball. But really it is only telling him he has to sit back down now.

When he sits back down and leans a little forward, he can see through the window the countryside moving past in the opposite direction. And the dark forest. And sometimes the small wooden train stations that are empty now that the war is over. And then the dark forest again. The train waddles right by the forest without a care in the world and then it waddles straight through the small wooden stations. He sees that the sky is beginning to darken and, in the distance, a broken bridge like a long arm with a hand that has been snapped off at the wrist. He sees other bridges too – some completely broken; others that have been put back together again with a strip of new wood or a slab of clean concrete and that makes him think of new patches on worn-out clothes.

He is wearing patched clothes. Clothes that are new, but at the same time old. All the boys wear the same kind of clothes. New and old. But they are not rags – nobody could say that about them. The big boys told Otto that the clothes had been cut out of dead soldiers’ uniforms and that the jumpers had been made out of wool unravelled from socks that had been stiff with blood or mufflers that had been wrapped around the soldiers’ necks when they died. Otto said, ‘I could be wearing part of your father’s uniform and you could be wearing part of mine.’ He wishes Otto had not told him all that about the uniforms. Because up till then he had quite liked his clothes. They had a good clean smell and they kept him warm. Now he is a little afraid of them. It is such a terrible feeling to be afraid of your own trousers, to feel your own jumper could be some sort of ghost.

Through the window again, and the forest again, rags of old snow caught between branches and the spaces between the trees getting wider in places so that sometimes you can see the shapes of firewood pickers bent to the ground like black hooks. Or an old jeep with branches growing out through the windows. And then what first looks like rows of sapling trees, but turns out to be hundreds of wooden crosses stuck into the ground. Row after row, a red rag tied around the neck of each one.

Bruno springs out of his seat, and his face turns a dark, excited red, his eyes sharpen with light.

‘Look – out there! Quick! The graves of the Ivans! Thousands of Ivans. Let’s hope they are burning in hell!’

‘The Red Army,’ Erich says, ‘they are not true soldiers like our fathers were. They are cowards – what they did to my sister and mother.’

‘And what did they do to your sister and mother?’ Bruno asks.

‘What did they do? What do you think they would do? Raped them, of course! Raped them and raped them!’

‘What does that mean, raped them and raped them?’ he hears himself ask.

There is a small silence. The big boys look at one another and then:

A snort from Bruno, a burst of laughter from the third big boy and finally another snort from Erich. And then all the boys (except the boy at the window) laughing with their puckered faces. Pucker and snigger and snort and point. Even the younger boys, laughing, laughing, pretending to understand what’s so funny.

‘He doesn’t know what it means!’ Erich cries. ‘He doesn’t even know what it means! Oh, the poor runt. He knows nothing about sex, you see. Nothing. Isn’t that so, Runt?’

He feels his feet jump and slap down on the floor as he stands to defend himself.

‘You never said it meant sex. I know what that means, I do know what it means! I do. I do.’

Frau Nurse calling out from the back of the carriage, ‘Quiet, please! Quiet or no supper for any of you.’

The drunken man comes into the carriage round about now. He knows him even before he comes in because he has already noticed his big, clumsy shape, bumping along through the train, slamming doors open and shut, stopping at seats to frighten the passengers.

The drunken man enters the carriage just as Frau Nurse is starting up the aisle. ‘Quiet up there, please! Quiet, I said, or no supper for any of you!’

The drunken man is an old drunken soldier. He is missing one arm, the empty sleeve of his raggedy tunic tucked into its raggedy pocket. He stays by the door rocking on his heels. Then he shouts all the way down at Frau Nurse, ‘Leave the boys be. They have been quiet long enough. You go back to where you came from, you American bitch, and leave our poor boys alone.’

His heart stops when he hears the drunken man talk this way to Frau Nurse. He wants to jump up and beat him with his fists. He knows that all the boys feel the same way. They want to bite and scratch and punch and kick the old soldier. And all the men too, reading their newspapers and stuffing their pipes. And the women doing their knitting – everyone wants to hit the drunken man. But nobody does. Nobody moves. Not even a little finger. Not even to utter one word.

The drunken man sways up the aisle, singing his head off about the old rotten bones in the ground. Frau Nurse has to step out of his way. The drunken man goes down the aisle once, leaving his stink behind him. He turns and comes back up it again, bringing his stink back with him. The empty sleeve has slipped out of his pocket and now it is rubbing off the tops of the seats, the way Frau Nurse’s cape does when she walks along the aisle.

He stops at their table, taking his time over each boy’s face, spurts of noisy breath coming down his nostrils. And then he says, ‘Look at them – just look! Little piglets off to the farm. Yes, that’s right, that’s where they are taking them. Off to the farm to fatten them up for the American market. Little piggy piglets.’

He turns then to the rest of the passengers, waves his one arm through the air. ‘This… this is what their fathers died for. This here is what it was all for – so we could fatten up our little piglets and send them off to the Ami market. Am I right? Or am I wrong? Can anyone tell me that?’

Then he turns back to their table, sticks out his neck and goes, ‘Kkrraw kkkrraww, eeek eeek. Sqweeeee. Piggy, piggy, pigs.’

When he finishes making his piggy noises, he stumbles back out of the carriage.

After he leaves nobody speaks or looks at each other. There isn’t a sound for such a long time, but for the sound of the train and the sniffly sound of Bruno crying.

The train pushes on. Before it gets dark the light turns purple. On the glass of the purple window, Frau Nurse’s cape and the white of her dress and the smear of her pretty face, asking in her funny accent if Erich and Bruno would care to be her helpers in serving supper. The shape of them sidling out from behind the table. Sidling out, with their heads bent low.

Coming and going, boy to boy, silently handing out apples. First, the apples and then black bricks of bread and butter. Last, the small bottles of milk. And then Bruno and Erich sit down again.

Outside, a German night is rising out of the darkness, the small clumped lights of a mountain village or a chain of street lamps pointing the way.

Inside, a train filled with yellow light. How strange to see all those pieces of light so close together. How strange to see any light at all. To be sitting with the windows left uncovered as the train flies along with its big wings of black smoke. And strange, too, that people outside can look right in. At the rows of boys in the harsh yellow light, or the single boys seated here and there between ordinary passengers, in their clean but not new clothes. Shame-faced and silent, carefully chewing on their bricks of black bread and trying so hard not to look like little piggies.

2

HE OPENS HIS EYES, finds himself alone on the seat in the corner by the window. He is holding his head in one hand, elbow stuck on top of the basket for support. The man with the long fingernails has gone and in his place a big woman is snoozing. Her head lilts and flops to the rhythm of the train as if someone has broken her neck. He notices, then, the box from the tart is lying on the floor, red showing through white. He lifts the lid with the tip of his little finger and peeps inside – all that remain are a few pastry flakes and two or three clots of jelly.

It had only taken him a few handfuls to demolish the tart before he had fallen asleep. It had lasted just long enough to get him through the first tunnel, and as it is only the first tunnel that he is scared of, he guesses the tart has done its job all right.

But it was not much of a pie, not for the price. Frau Aunt had been right: the baker was nothing but a smiling thief.

His hands are sticky. His mouth grimed with oversweet fruit. His belly aches from greed and shame, and now dread too, as he thinks of how easily he could be found out. He screws the empty box into the shape of a bow and then heels it under his seat. He will say nothing about the tart – it will be as if it never existed. But supposing Mrs Kaplan writes to say thank you for the other gifts in the basket? (I did so enjoy the apple pie and the French pâté was quite delicious…) Frau Aunt would not be pleased when the strawberry tart got no mention. She would be sure to write back fishing for compliments. (I do so hope you enjoyed the tart… I so look forward to hearing how you enjoyed the… Thank you so much for eating the strawberry tart which came from that very expensive French bakery on Fifth Avenue.) Maybe it would be better if he got rid of the basket altogether? He could pretend that it was stolen by the man with the long fingernails. Or he could throw it out the window. Leave it in the washroom, even? But if he pulls the window right down, the lady opposite will be sure to wake up and if he leaves it in the washroom Harry’s porter friend will probably find it and it wouldn’t take long for him to figure out who it belonged to, and when Mrs Kaplan gets on in Boston, the porter might meet her at the door with the basket held out. He stands up and places the basket on the overhead rack as far away from his suitcase as it can go. He will simply forget the basket. Pretend that it just slipped his mind and he walked off without it. He won’t notice till they get to Mrs Kaplan’s house and by then it will be too late to do anything about it.

When he sits back down, he sees there’s a stain on his pants. He sticks his finger into his mouth and tries to clean the stain off with his spit. He rubs it a few times but that only makes it worse. He takes his handkerchief out of his pocket and goes at it again. The stain spreads across his thigh. Now it looks as if he pissed in his pants. He pushes harder and harder into the stain. His head feels heavy and sore. He grows tired of trying to fix the stain, tired of trying to keep his eyes open. Tired of worrying about a stupid pie with a fancy French name. He edges back into the corner and places his head against the glass of the window. How soothing it is to rest his head against the cool glass, to feel the movement of the train grinding through his skull and into his brain, rocking his worries away.

In his mind, he finds Frau Nurse again. They are in the toilet of the train. And his feet. His feet are far off the floor, his pants looped round his ankles while his winky just lies there, like a small, fat maggot, doing nothing. He is torn between the shame of all that and the pleasure of having her long safe hands around his middle holding him up, the smell of her soap.

She says, ‘I’m keeping my eyes shut, I can’t see a thing. Now off you go. Give us a tinkle.’

Above, flickering bullet holes of light in the roof. And he is talking and talking, questions mostly, hoping the splash will come and go and not be heard behind the sounds of the train and the sound of his questions.

‘Why is the light through the holes so bright – is the night over already?’

‘We’re going through a station. No more blackouts. Remember?’

‘But not Berlin?’

‘I’ve told you a million times, we are not going near Berlin.’

‘So no big tunnels, Frau Nurse?’

‘No big tunnels, I told you.’

‘But the drunken soldier – Frau Nurse, why did he say you were American if you are English?’

‘I am English.’

‘But why do you work in the American camp then?’

‘Because we are allies.’

‘But allies – doesn’t that mean people who want to kill us?’

‘No, it means we are on the same side – like you and me, we are on the same side.’

‘But what if there is another war – will we be on the same side then?’

‘There won’t be another war, I can promise you that. Now shh, shh, concentrate, there’s a good boy – we can’t stay here all night, you know. Christ, my ruddy arms are breaking.’

‘Frau Nurse – guess what? A boy in my last camp said there are people buried under the gardens and parks all over Germany. And in the sea, dead sailors sometimes just bob up and start floating around. That’s what he said.’

‘Did he, indeed?’

‘Yes. And, and, one time after a raid, I saw a dead horse and a man said the Americans killed it with a machine gun, poking out of the door of the aircraft, because Americans hate horses, you see.’

‘What about the cowboys, then? They’re American and they love their horses – don’t they?’

‘Oh, yes. The cowboys. Did the cowboys fight in the war? Oh, wait, Frau Nurse, wait, it’s coming now I think, here it is now, oh yesss.’

He opens his eyes a fraction, looks at his legs reaching all the way down to the floor and his feet in their American sneakers. There is a sound of low American voices and he sees a woman’s legs in pale stockings crossed at the ankle, polished shoes with a gold buckle and the hem of a daisy dress. He tilts his chin slightly and now, through the slit, there is a little bit more of the daisy dress and hands on the lap of it in white lace gloves. And past that, the leg of a boy, his feet in sandals, swinging back and forward under the seat.

He tries to keep Frau Nurse in his head, to stay with her and her lemon-soap smell; he wants to tell her everything he has ever seen and everything he knows. He wants to ask her question after question just to hear the sound of her voice.

Frau Nurse helping him to pull up his pants, then taking his hand and stretching it out under a flow of water. ‘Water. Say it.’

He says it.

‘Not Vvva vvva. Wwwa wwwa. Say it again. Water. Good. And again.’

‘But why do I have to keep saying it again? And again?’

‘Because you have to learn how to speak English.’

‘Wwwa, waaa, water. But why do I have to speak English?’

‘Because that’s what they speak where you’re going. And something else you have to do is to stop asking so many questions.’

‘What questions?’

‘All these questions about the war, for a start. You have to stop talking about soldiers and dead horses and guns – all that rot. Where you are going, they had no war. At least not at home. You don’t want to go bringing it with you.’

‘Bringing what with me?’

‘The war.’

‘But that’s so funny! How can I bring a war with me?’

Frau Nurse lifting her long finger, tapping him in three places: his forehead and then his stomach and then his heart.

‘You can bring it in here, and in here, and in there,’ she says.

He opens his eyes another fraction. From the far end of the seat, a boy’s voice begins to squeak. ‘Look, Grandma, he’s awake, he’s opening his eyes!’

The daisy dress begins to move; a woman’s face rises out of it and says, ‘Well, hello, sleepy head, we were just about to wake you up! And now here you are, just in time for our famous sunset. I’m Mrs Kaplan and this young man here is my grandson, Richie. Welcome to the Narrow Land – that’s what we call this part of Cape Cod.’

‘Ask him, Grandma,’ the boy squeaks again, ‘ask him if that’s his basket up there on the rack!’

He opens his eyes fully, turns his face to the window, finds that Germany has gone. Instead of black icy rivers and walls of dark forest, there are low, soft hills and wide open fields.

He looks back into the car, then back through the window. Everything he sees is rinsed in red light – the boy, the woman, the seats in the train, the hills outside, the little train station. Everything.

Mrs Aitch

1

HIS SLOW FOOTSTEP CROSSES