8,39 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Allison & Busby

- Kategorie: Wissenschaft und neue Technologien

- Sprache: Englisch

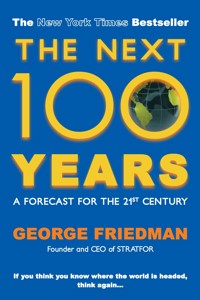

In his long-awaited and provocative book, George Friedman turns his eye on the future-offering a lucid, highly readable forecast of the changes we can expect around the world during the twenty-first century. He explains where and why future wars will erupt (and how they will be fought), which nations will gain and lose economic and political power, and how new technologies and cultural trends will alter the way we live in the new century. The Next 100 Years draws on a fascinating exploration of history and geopolitical patterns dating back hundreds of years. Friedman shows that we are now, for the first time in half a millennium, at the dawn of a new era-with changes in store.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 448

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2010

Ähnliche

A FORECAST FOR THE 21ST CENTURY

GEORGE FRIEDMAN

Epigraph

To him who looks upon the world rationally, the world in turn presents a rational aspect. The relation is mutual.

—GEORGE W. F. HEGEL

CONTENTS

Title Page

Dedication

Epigraph

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

AUTHOR’S NOTE

OVERTURE: AN INTRODUCTION TO THE AMERICAN AGE

CHAPTER 1 THE DAWN OF THE AMERICAN AGE

CHAPTER 2 EARTHQUAKE: THE U.S.–JIHADIST WAR

CHAPTER 3 POPULATION, COMPUTERS, AND CULTURE WARS

CHAPTER 4 THE NEW FAULT LINES

CHAPTER 5 CHINA 2020: PAPER TIGER

CHAPTER 6 RUSSIA 2020: REMATCH

CHAPTER 7 AMERICAN POWER AND THE CRISIS OF 2030

CHAPTER 8 A NEW WORLD EMERGES

CHAPTER 9 THE 2040S: PRELUDE TO WAR

CHAPTER 10 PREPARING FOR WAR

CHAPTER 11 WORLD WAR: A SCENARIO

CHAPTER 12 THE 2060S: A GOLDEN DECADE

CHAPTER 13 2080: THE UNITED STATES, MEXICO, AND THE STRUGGLE FOR THE GLOBAL HEARTLAND

EPILOGUE

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

About the Author

Copyright

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

ATLANTIC EUROPE39

THE SOVIET EMPIRE47

YUGOSLAVIA AND THE BALKANS57

EARTHQUAKE ZONE59

ISLAMIC WORLD—MODERN60

U.S. RIVER SYSTEM68

SOUTH AMERICA: IMPASSABLE TERRAIN69

PACIFIC TRADE ROUTES103

SUCCESSOR STATES TO THE SOVIET UNION107

UKRAINE’S STRATEGIC SIGNIFICANCE109

FOUR EUROPES113

TURKEY IN 2008120

OTTOMAN EMPIRE121

MEXICO PRIOR TO TEXAS REBELLION125

CHINA: IMPASSABLE TERRAIN131

CHINA’S POPULATION DENSITY132

SILK ROAD133

THE CAUCASUS156

CENTRAL ASIA159

POACHER’S PARADISE195

JAPAN199

MIDDLE EAST SEA LANES223

POLAND 1660227

THE SKAGERRAK STRAITS229

TURKISH SPHERE OF INFLUENCE 2050284

U.S. HISPANIC POPULATION (2000)315

LEVELS OF ECONOMIC AND SOCIAL DEVELOPMENT324

MEXICAN SOCIAL AND ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT325

AUTHOR’S NOTE

I have no crystal ball. I do, however, have a method that has served me well, imperfect though it might be, in understanding the past and anticipating the future. Underneath the disorder of history, my task is to try to see the order—and to anticipate what events, trends, and technology that order will bring forth. Forecasting a hundred years ahead may appear to be a frivolous activity, but, as I hope you will see, it is a rational, feasible process, and it is hardly frivolous. I will have grandchildren in the not-distant future, and some of them will surely be alive in the twenty-second century. That thought makes all of this very real.

In this book, I am trying to transmit a sense of the future. I will, of course, get many details wrong. But the goal is to identify the major tendencies—geopolitical, technological, demographic, cultural, military—in their broadest sense, and to define the major events that might take place. I will be satisfied if I explain something about how the world works today, and how that, in turn, defines how it will work in the future. And I will be delighted if my grandchildren, glancing at this book in 2100, have reason to say, “Not half bad.”

OVERTURE

AN INTRODUCTIONTO THE AMERICAN AGE

Imagine that you were alive in the summer of 1900, living in London, then the capital of the world. Europe ruled the Eastern Hemisphere. There was hardly a place that, if not ruled directly, was not indirectly controlled from a European capital. Europe was at peace and enjoying unprecedented prosperity. Indeed, European interdependence due to trade and investment was so great that serious people were claiming that war had become impossible—and if not impossible, would end within weeks of beginning—because global financial markets couldn’t withstand the strain. The future seemed fixed: a peaceful, prosperous Europe would rule the world.

Imagine yourself now in the summer of 1920. Europe had been torn apart by an agonizing war. The continent was in tatters. The Austro-Hungarian, Russian, German, and Ottoman empires were gone and millions had died in a war that lasted for years. The war ended when an American army of a million men intervened—an army that came and then just as quickly left. Communism dominated Russia, but it was not clear that it could survive. Countries that had been on the periphery of European power, like the United States and Japan, suddenly emerged as great powers. But one thing was certain—the peace treaty that had been imposed on Germany guaranteed that it would not soon reemerge.

Imagine the summer of 1940. Germany had not only reemerged but conquered France and dominated Europe. Communism had survived and the Soviet Union now was allied with Nazi Germany. Great Britain alone stood against Germany, and from the point of view of most reasonable people, the war was over. If there was not to be a thousand-year Reich, then certainly Europe’s fate had been decided for a century. Germany would dominate Europe and inherit its empire.

Imagine now the summer of 1960. Germany had been crushed in the war, defeated less than five years later. Europe was occupied, split down the middle by the United States and the Soviet Union. The European empires were collapsing, and the United States and Soviet Union were competing over who would be their heir. The United States had the Soviet Union surrounded and, with an overwhelming arsenal of nuclear weapons, could annihilate it in hours. The United States had emerged as the global superpower. It dominated all of the world’s oceans, and with its nuclear force could dictate terms to anyone in the world. Stalemate was the best the Soviets could hope for—unless the Soviets invaded Germany and conquered Europe. That was the war everyone was preparing for. And in the back of everyone’s mind, the Maoist Chinese, seen as fanatical, were the other danger.

Now imagine the summer of 1980. The United States had been defeated in a seven-year war—not by the Soviet Union, but by communist North Vietnam. The nation was seen, and saw itself, as being in retreat. Expelled from Vietnam, it was then expelled from Iran as well, where the oil fields, which it no longer controlled, seemed about to fall into the hands of the Soviet Union. To contain the Soviet Union, the United States had formed an alliance with Maoist China—the American president and the Chinese chairman holding an amiable meeting in Beijing. Only this alliance seemed able to contain the powerful Soviet Union, which appeared to be surging.

Imagine now the summer of 2000. The Soviet Union had completely collapsed. China was still communist in name but had become capitalist in practice. NATO had advanced into Eastern Europe and even into the former Soviet Union. The world was prosperous and peaceful. Everyone knew that geopolitical considerations had become secondary to economic considerations, and the only problems were regional ones in basket cases like Haiti or Kosovo.

Then came September 11, 2001, and the world turned on its head again.

At a certain level, when it comes to the future, the only thing one can be sure of is that common sense will be wrong. There is no magic twenty-year cycle; there is no simplistic force governing this pattern. It is simply that the things that appear to be so permanent and dominant at any given moment in history can change with stunning rapidity. Eras come and go. In international relations, the way the world looks right now is not at all how it will look in twenty years … or even less. The fall of the Soviet Union was hard to imagine, and that is exactly the point. Conventional political analysis suffers from a profound failure of imagination. It imagines passing clouds to be permanent and is blind to powerful, long-term shifts taking place in full view of the world.

If we were at the beginning of the twentieth century, it would be impossible to forecast the particular events I’ve just listed. But there are some things that could have been—and, in fact, were—forecast. For example, it was obvious that Germany, having united in 1871, was a major power in an insecure position (trapped between Russia and France) and wanted to redefine the European and global systems. Most of the conflicts in the first half of the twentieth century were about Germany’s status in Europe. While the times and places of wars couldn’t be forecast, the probability that there would be a war could be and was forecast by many Europeans.

The harder part of this equation would be forecasting that the wars would be so devastating and that after the first and second world wars were over, Europe would lose its empire. But there were those, particularly after the invention of dynamite, who predicted that war would now be catastrophic. If the forecasting on technology had been combined with the forecasting on geopolitics, the shattering of Europe might well have been predicted. Certainly the rise of the United States and Russia was predicted in the nineteenth century. Both Alexis de Tocqueville and Friedrich Nietzsche forecast the preeminence of these two countries. So, standing at the beginning of the twentieth century, it would have been possible to forecast its general outlines, with discipline and some luck.

THE TWENTY-FIRST CENTURY

Standing at the beginning of the twenty-first century, we need to identify the single pivotal event for this century, the equivalent of German unification for the twentieth century. After the debris of the European empire is cleared away, as well as what’s left of the Soviet Union, one power remains standing and overwhelmingly powerful. That power is the United States. Certainly, as is usually the case, the United States currently appears to be making a mess of things around the world. But it’s important not to be confused by the passing chaos. The United States is economically, militarily, and politically the most powerful country in the world, and there is no real challenger to that power. Like the Spanish-American War, a hundred years from now the war between the United States and the radical Islamists will be little remembered regardless of the prevailing sentiment of this time.

Ever since the Civil War, the United States has been on an extraordinary economic surge. It has turned from a marginal developing nation into an economy bigger than the next four countries combined. Militarily, it has gone from being an insignificant force to dominating the globe. Politically, the United States touches virtually everything, sometimes intentionally and sometimes simply because of its presence. As you read this book, it will seem that it is America-centric, written from an American point of view. That may be true, but the argument I’m making is that the world does, in fact, pivot around the United States.

This is not only due to American power. It also has to do with a fundamental shift in the way the world works. For the past five hundred years, Europe was the center of the international system, its empires creating a single global system for the first time in human history. The main highway to Europe was the North Atlantic. Whoever controlled the North Atlantic controlled access to Europe—and Europe’s access to the world. The basic geography of global politics was locked into place.

Then, in the early 1980s, something remarkable happened. For the first time in history, transpacific trade equaled transatlantic trade. With Europe reduced to a collection of secondary powers after World War II, and the shift in trade patterns, the North Atlantic was no longer the single key to anything. Now whatever country controlled both the North Atlantic and the Pacific could control, if it wished, the world’s trading system, and therefore the global economy. In the twenty-first century, any nation located on both oceans has a tremendous advantage.

Given the cost of building naval power and the huge cost of deploying it around the world, the power native to both oceans became the preeminent actor in the international system for the same reason that Britain dominated the nineteenth century: it lived on the sea it had to control. In this way, North America has replaced Europe as the center of gravity in the world, and whoever dominates North America is virtually assured of being the dominant global power. For the twenty-first century at least, that will be the United States.

The inherent power of the United States coupled with its geographic position makes the United States the pivotal actor of the twenty-first century. That certainly doesn’t make it loved. On the contrary, its power makes it feared. The history of the twenty-first century, therefore, particularly the first half, will revolve around two opposing struggles. One will be secondary powers forming coalitions to try to contain and control the United States. The second will be the United States acting preemptively to prevent an effective coalition from forming.

If we view the beginning of the twenty-first century as the dawn of the American Age (superseding the European Age), we see that it began with a group of Muslims seeking to re-create the Caliphate—the great Islamic empire that once ran from the Atlantic to the Pacific. Inevitably, they had to strike at the United States in an attempt to draw the world’s primary power into war, trying to demonstrate its weakness in order to trigger an Islamic uprising. The United States responded by invading the Islamic world. But its goal wasn’t victory. It wasn’t even clear what victory would mean. Its goal was simply to disrupt the Islamic world and set it against itself, so that an Islamic empire could not emerge.

The United States doesn’t need to win wars. It needs to simply disrupt things so the other side can’t build up sufficient strength to challenge it. On one level, the twenty-first century will see a series of confrontations involving lesser powers trying to build coalitions to control American behavior and the United States’ mounting military operations to disrupt them. The twenty-first century will see even more war than the twentieth century, but the wars will be much less catastrophic, because of both technological changes and the nature of the geopolitical challenge.

As we’ve seen, the changes that lead to the next era are always shockingly unexpected, and the first twenty years of this new century will be no exception. The U.S.–Islamist war is already ending and the next conflict is in sight. Russia is recreating creating its old sphere of influence, and that sphere of influence will inevitably challenge the United States. The Russians will be moving westward on the great northern European plain. As Russia reconstructs its power, it will encounter the U.S.-dominated NATO in the three Baltic countries—Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania—as well as in Poland. There will be other points of friction in the early twenty-first century, but this new cold war will supply the flash points after the U.S.–Islamist war dies down.

The Russians can’t avoid trying to reassert power, and the United States can’t avoid trying to resist. But in the end Russia can’t win. Its deep internal problems, massively declining population, and poor infrastructure ultimately make Russia’s long-term survival prospects bleak. And the second cold war, less frightening and much less global than the first, will end as the first did, with the collapse of Russia.

There are many who predict that China is the next challenger to the United States, not Russia. I don’t agree with that view for three reasons. First, when you look at a map of China closely, you see that it is really a very isolated country physically. With Siberia in the north, the Himalayas and jungles to the south, and most of China’s population in the eastern part of the country, the Chinese aren’t going to easily expand. Second, China has not been a major naval power for centuries, and building a navy requires a long time not only to build ships but to create well-trained and experienced sailors.

Third, there is a deeper reason for not worrying about China. China is inherently unstable. Whenever it opens its borders to the outside world, the coastal region becomes prosperous, but the vast majority of Chinese in the interior remain impoverished. This leads to tension, conflict, and instability. It also leads to economic decisions made for political reasons, resulting in inefficiency and corruption. This is not the first time that China has opened itself to foreign trade, and it will not be the last time that it becomes unstable as a result. Nor will it be the last time that a figure like Mao emerges to close the country off from the outside, equalize the wealth—or poverty—and begin the cycle anew. There are some who believe that the trends of the last thirty years will continue indefinitely. I believe the Chinese cycle will move to its next and inevitable phase in the coming decade. Far from being a challenger, China is a country the United States will be trying to bolster and hold together as a counterweight to the Russians. Current Chinese economic dynamism does not translate into long-term success.

In the middle of the century, other powers will emerge, countries that aren’t thought of as great powers today, but that I expect will become more powerful and assertive over the next few decades. Three stand out in particular. The first is Japan. It’s the second-largest economy in the world and the most vulnerable, being highly dependent on the importation of raw materials, since it has almost none of its own. With a history of militarism, Japan will not remain the marginal pacifistic power it has been. It cannot. Its own deep population problems and abhorrence of large-scale immigration will force it to look for new workers in other countries. Japan’s vulnerabilities, which I’ve written about in the past and which the Japanese have managed better than I’ve expected up until this point, in the end will force a shift in policy.

Then there is Turkey, currently the seventeenth-largest economy in the world. Historically, when a major Islamic empire has emerged, it has been dominated by the Turks. The Ottomans collapsed at the end of World War I, leaving modern Turkey in its wake. But Turkey is a stable platform in the midst of chaos. The Balkans, the Caucasus, and the Arab world to the south are all unstable. As Turkey’s power grows—and its economy and military are already the most powerful in the region—so will Turkish influence.

Finally there is Poland. Poland hasn’t been a great power since the sixteenth century. But it once was—and, I think, will be again. Two factors make this possible. First will be the decline of Germany. Its economy is large and still growing, but it has lost the dynamism it has had for two centuries. In addition, its population is going to fall dramatically in the next fifty years, further undermining its economic power. Second, as the Russians press on the Poles from the east, the Germans won’t have an appetite for a third war with Russia. The United States, however, will back Poland, providing it with massive economic and technical support. Wars—when your country isn’t destroyed—stimulate economic growth, and Poland will become the leading power in a coalition of states facing the Russians.

Japan, Turkey, and Poland will each be facing a United States even more confident than it was after the second fall of the Soviet Union. That will be an explosive situation. As we will see during the course of this book, the relationships among these four countries will greatly affect the twenty-first century, leading, ultimately, to the next global war. This war will be fought differently from any in history—with weapons that are today in the realm of science fiction. But as I will try to outline, this mid-twenty-first century conflict will grow out of the dynamic forces born in the early part of the new century.

Tremendous technical advances will come out of this war, as they did out of World War II, and one of them will be especially critical. All sides will be looking for new forms of energy to substitute for hydrocarbons, for many obvious reasons. Solar power is theoretically the most efficient energy source on earth, but solar power requires massive arrays of receivers. Those receivers take up a lot of space on the earth’s surface and have many negative environmental impacts—not to mention being subject to the disruptive cycles of night and day. During the coming global war, however, concepts developed prior to the war for space-based electrical generation, beamed to earth in the form of microwave radiation, will be rapidly translated from prototype to reality. Getting a free ride on the back of military space launch capability, the new energy source will be underwritten in much the same way as the Internet or the railroads were, by government support. And that will kick off a massive economic boom.

But underlying all of this will be the single most important fact of the twenty-first century: the end of the population explosion. By 2050, advanced industrial countries will be losing population at a dramatic rate. By 2100, even the most underdeveloped countries will have reached birthrates that will stabilize their populations. The entire global system has been built since 1750 on the expectation of continually expanding populations. More workers, more consumers, more soldiers—this was always the expectation. In the twenty-first century, however, that will cease to be true. The entire system of production will shift. The shift will force the world into a greater dependence on technology—particularly robots that will substitute for human labor, and intensified genetic research (not so much for the purpose of extending life but to make people productive longer).

What will be the more immediate result of a shrinking world population? Quite simply, in the first half of the century, the population bust will create a major labor shortage in advanced industrial countries. Today, developed countries see the problem as keeping immigrants out. Later in the first half of the twenty-first century, the problem will be persuading them to come. Countries will go so far as to pay people to move there. This will include the United States, which will be competing for increasingly scarce immigrants and will be doing everything it can to induce Mexicans to come to the United States—an ironic but inevitable shift.

These changes will lead to the final crisis of the twenty-first century. Mexico currently is the fifteenth-largest economy in the world. As the Europeans slip out, the Mexicans, like the Turks, will rise in the rankings until by the late twenty-first century they will be one of the major economic powers in the world. During the great migration north encouraged by the United States, the population balance in the old Mexican Cession (that is, the areas of the United States taken from Mexico in the nineteenth century) will shift dramatically until much of the region is predominantly Mexican.

The social reality will be viewed by the Mexican government simply as rectification of historical defeats. By 2080 I expect there to be a serious confrontation between the United States and an increasingly powerful and assertive Mexico. That confrontation may well have unforeseen consequences for the United States, and will likely not end by 2100.

Much of what I’ve said here may seem pretty hard to fathom. The idea that the twenty-first century will culminate in a confrontation between Mexico and the United States is certainly hard to imagine in 2009, as is a powerful Turkey or Poland. But go back to the beginning of this chapter, when I described how the world looked at twenty-year intervals during the twentieth century, and you can see what I’m driving at: common sense is the one thing that will certainly be wrong.

Obviously, the more granular the description, the less reliable it gets. It is impossible to forecast precise details of a coming century—apart from the fact that I’ll be long dead by then and won’t know what mistakes I made. But it’s my contention that it is indeed possible to see the broad outlines of what is going to happen, and to try to give it some definition, however speculative that definition might be. That’s what this book is about.

FORECASTING A HUNDRED YEARS AHEAD

Before I delve into any details of global wars, population trends, or technological shifts, it is important that I address my method—that is, precisely how I can forecast what I do. I don’t intend to be taken seriously on the details of the war in 2050 that I forecast. But I do want to be taken seriously in terms of how wars will be fought then, about the centrality of American power, about the likelihood of other countries challenging that power, and about some of the countries I think will—and won’t—challenge that power. And doing that takes some justification. The idea of a U.S.–Mexican confrontation and even war will leave most reasonable people dubious, but I would like to demonstrate why and how these assertions can be made.

One point I’ve already made is that reasonable people are incapable of anticipating the future. The old New Left slogan “Be Practical, Demand the Impossible” needs to be changed: “Be Practical, Expect the Impossible.” This idea is at the heart of my method. From another, more substantial perspective, this is called geopolitics.

Geopolitics is not simply a pretentious way of saying “international relations.” It is a method for thinking about the world and forecasting what will happen down the road. Economists talk about an invisible hand, in which the self-interested, short-term activities of people lead to what Adam Smith called “the wealth of nations.” Geopolitics applies the concept of the invisible hand to the behavior of nations and other international actors. The pursuit of short-term self-interest by nations and by their leaders leads, if not to the wealth of nations, then at least to predictable behavior and, therefore, the ability to forecast the shape of the future international system.

Geopolitics and economics both assume that the players are rational, at least in the sense of knowing their own short-term self-interest. As rational actors, reality provides them with limited choices. It is assumed that, on the whole, people and nations will pursue their self-interest, if not flawlessly, then at least not randomly. Think of a chess game. On the surface, it appears that each player has twenty potential opening moves. In fact, there are many fewer because most of these moves are so bad that they quickly lead to defeat. The better you are at chess, the more clearly you see your options, and the fewer moves there actually are available. The better the player, the more predictable the moves. The grandmaster plays with absolute predictable precision—until that one brilliant, unexpected stroke.

Nations behave the same way. The millions or hundreds of millions of people who make up a nation are constrained by reality. They generate leaders who would not become leaders if they were irrational. Climbing to the top of millions of people is not something fools often do. Leaders understand their menu of next moves and execute them, if not flawlessly, then at least pretty well. An occasional master will come along with a stunningly unexpected and successful move, but for the most part, the act of governance is simply executing the necessary and logical next step. When politicians run a country’s foreign policy, they operate the same way. If a leader dies and is replaced, another emerges and more likely than not continues what the first one was doing.

I am not arguing that political leaders are geniuses, scholars, or even gentlemen and ladies. Simply, political leaders know how to be leaders or they wouldn’t have emerged as such. It is the delight of all societies to belittle their political leaders, and leaders surely do make mistakes. But the mistakes they make, when carefully examined, are rarely stupid. More likely, mistakes are forced on them by circumstance. We would all like to believe that we—or our favorite candidate—would never have acted so stupidly. It is rarely true. Geopolitics therefore does not take the individual leader very seriously, any more than economics takes the individual businessman too seriously. Both are players who know how to manage a process but are not free to break the very rigid rules of their professions.

Politicians are therefore rarely free actors. Their actions are determined by circumstances, and public policy is a response to reality. Within narrow margins, political decisions can matter. But the most brilliant leader of Iceland will never turn it into a world power, while the stupidest leader of Rome at its height could not undermine Rome’s fundamental power. Geopolitics is not about the right and wrong of things, it is not about the virtues or vices of politicians, and it is not about foreign policy debates. Geopolitics is about broad impersonal forces that constrain nations and human beings and compel them to act in certain ways.

The key to understanding economics is accepting that there are always unintended consequences. Actions people take for their own good reasons have results they don’t envision or intend. The same is true with geopolitics. It is doubtful that the village of Rome, when it started its expansion in the seventh century BC, had a master plan for conquering the Mediterranean world five hundred years later. But the first action its inhabitants took against neighboring villages set in motion a process that was both constrained by reality and filled with unintended consequences. Rome wasn’t planned, and neither did it just happen.

Geopolitical forecasting, therefore, doesn’t assume that everything is predetermined. It does mean that what people think they are doing, what they hope to achieve, and what the final outcome is are not the same things. Nations and politicians pursue their immediate ends, as constrained by reality as a grandmaster is constrained by the chessboard, the pieces, and the rules. Sometimes they increase the power of the nation. Sometimes they lead the nation to catastrophe. It is rare that the final outcome will be what they initially intended to achieve.

Geopolitics assumes two things. First, it assumes that humans organize themselves into units larger than families, and that by doing this, they must engage in politics. It also assumes that humans have a natural loyalty to the things they were born into, the people and the places. Loyalty to a tribe, a city, or a nation is natural to people. In our time, national identity matters a great deal. Geopolitics teaches that the relationship between these nations is a vital dimension of human life, and that means that war is ubiquitous.

Second, geopolitics assumes that the character of a nation is determined to a great extent by geography, as is the relationship between nations. We use the term geography broadly. It includes the physical characteristics of a location, but it goes beyond that to look at the effects of a place on individuals and communities. In antiquity, the difference between Sparta and Athens was the difference between a landlocked city and a maritime empire. Athens was wealthy and cosmopolitan, while Sparta was poor, provincial, and very tough. A Spartan was very different from an Athenian in both culture and politics.

If you understand those assumptions, then it is possible to think about large numbers of human beings, linked together through natural human bonds, constrained by geography, acting in certain ways. The United States is the United States and therefore must behave in a certain way. The same goes for Japan or Turkey or Mexico. When you drill down and see the forces that are shaping nations, you can see that the menu from which they choose is limited.

The twenty-first century will be like all other centuries. There will be wars, there will be poverty, there will be triumphs and defeats. There will be tragedy and good luck. People will go to work, make money, have children, fall in love, and come to hate. That is the one thing that is not cyclical. It is the permanent human condition. But the twenty-first century will be extraordinary in two senses: it will be the beginning of a new age, and it will see a new global power astride the world. That doesn’t happen very often.

We are now in an America-centric age. To understand this age, we must understand the United States, not only because it is so powerful but because its culture will permeate the world and define it. Just as French culture and British culture were definitive during their times of power, so American culture, as young and barbaric as it is, will define the way the world thinks and lives. So studying the twenty-first century means studying the United States.

If there were only one argument I could make about the twenty-first century, it would be that the European Age has ended and that the North American Age has begun, and that North America will be dominated by the United States for the next hundred years. The events of the twenty-first century will pivot around the United States. That doesn’t guarantee that the United States is necessarily a just or moral regime. It certainly does not mean that America has yet developed a mature civilization. It does mean that in many ways the history of the United States will be the history of the twenty-first century.

CHAPTER 1

THE DAWN OF THE AMERICAN AGE

There is a deep-seated belief in America that the United States is approaching the eve of its destruction. Read letters to the editor, peruse the Web, and listen to public discourse. Disastrous wars, uncontrolled deficits, high gasoline prices, shootings at universities, corruption in business and government, and an endless litany of other shortcomings—all of them quite real—create a sense that the American dream has been shattered and that America is past its prime. If that doesn’t convince you, listen to Europeans. They will assure you that America’s best day is behind it.

The odd thing is that all of this foreboding was present during the presidency of Richard Nixon, together with many of the same issues. There is a continual fear that American power and prosperity are illusory, and that disaster is just around the corner. The sense transcends ideology. Environmentalists and Christian conservatives are both delivering the same message. Unless we repent of our ways, we will pay the price—and it may be too late already.

It’s interesting to note that the nation that believes in its manifest destiny has not only a sense of impending disaster but a nagging feeling that the country simply isn’t what it used to be. We have a deep sense of nostalgia for the 1950s as a “simpler” time. This is quite a strange belief. With the Korean War and McCarthy at one end, Little Rock in the middle, and Sputnik and Berlin at the other end, and the very real threat of nuclear war throughout, the 1950s was actually a time of intense anxiety and foreboding. A widely read book published in the 1950s was entitled The Age of Anxiety. In the 1950s, they looked back nostalgically at an earlier America, just as we look back nostalgically at the 1950s.

American culture is the manic combination of exultant hubris and profound gloom. The net result is a sense of confidence constantly undermined by the fear that we may be drowned by melting ice caps caused by global warming or smitten dead by a wrathful God for gay marriage, both outcomes being our personal responsibility. American mood swings make it hard to develop a real sense of the United States at the beginning of the twenty-first century. But the fact is that the United States is stunningly powerful. It may be that it is heading for a catastrophe, but it is hard to see one when you look at the basic facts.

Let’s consider some illuminating figures. Americans constitute about 4 percent of the world’s population but produce about 26 percent of all goods and services. In 2007 U.S. gross domestic product was about $14 trillion, compared to the world’s GDP of $54 trillion—about 26 percent of the world’s economic activity takes place in the United States. The next largest economy in the world is Japan’s, with a GDP of about $4.4 trillion—about a third the size of ours. The American economy is so huge that it is larger than the economies of the next four countries combined: Japan, Germany, China, and the United Kingdom.

Many people point at the declining auto and steel industries, which a generation ago were the mainstays of the American economy, as examples of a current deindustrialization of the United States. Certainly, a lot of industry has moved overseas. That has left the United States with industrial production of only $2.8 trillion (in 2006): the largest in the world, more than twice the size of the next largest industrial power, Japan, and larger than Japan’s and China’s industries combined.

There is talk of oil shortages, which certainly seem to exist and will undoubtedly increase. However, it is important to realize that the United States produced 8.3 million barrels of oil every day in 2006. Compare that with 9.7 million for Russia and 10.7 million for Saudi Arabia. U.S. oil production is 85 percent that of Saudi Arabia. The United States produces more oil than Iran, Kuwait, or the United Arab Emirates. Imports of oil into the country are vast, but given its industrial production, that’s understandable. Comparing natural gas production in 2006, Russia was in first place with 22.4 trillion cubic feet and the United States was second with 18.7 trillion cubic feet. U.S. natural gas production is greater than that of the next five producers combined. In other words, although there is great concern that the United States is wholly dependent on foreign energy, it is actually one of the world’s largest energy producers.

Given the vast size of the American economy, it is interesting to note that the United States is still underpopulated by global standards. Measured in inhabitants per square kilometer, the world’s average population density is 49. Japan’s is 338, Germany’s is 230, and America’s is only 31. If we exclude Alaska, which is largely uninhabitable, U.S. population density rises to 34. Compared to Japan or Germany, or the rest of Europe, the United States is hugely underpopulated. Even when we simply compare population in proportion to arable land—land that is suitable for agriculture—America has five times as much land per person as Asia, almost twice as much as Europe, and three times as much as the global average. An economy consists of land, labor, and capital. In the case of the United States, these numbers show that the nation can still grow—it has plenty of room to increase all three.

There are many answers to the question of why the U.S. economy is so powerful, but the simplest answer is military power. The United States completely dominates a continent that is invulnerable to invasion and occupation and in which its military overwhelms those of its neighbors. Virtually every other industrial power in the world has experienced devastating warfare in the twentieth century. The United States waged war, but America itself never experienced it. Military power and geographical reality created an economic reality. Other countries have lost time recovering from wars. The United States has not. It has actually grown because of them.

Consider this simple fact that I’ll be returning to many times. The United States Navy controls all of the oceans of the world. Whether it’s a junk in the South China Sea, a dhow off the African coast, a tanker in the Persian Gulf, or a cabin cruiser in the Caribbean, every ship in the world moves under the eyes of American satellites in space and its movement is guaranteed—or denied—at will by the U.S. Navy. The combined naval force of the rest of the world doesn’t come close to equaling that of the U.S. Navy.

This has never happened before in human history, even with Britain. There have been regionally dominant navies, but never one that was globally and overwhelmingly dominant. This has meant that the United States could invade other countries—but never be invaded. It has meant that in the final analysis the United States controls international trade. It has become the foundation of American security and American wealth. Control of the seas emerged after World War II, solidified during the final phase of the European Age, and is now the flip side of American economic power, the basis of its military power.

Whatever passing problems exist for the United States, the most important factor in world affairs is the tremendous imbalance of economic, military, and political power. Any attempt to forecast the twenty-first century that does not begin with the recognition of the extraordinary nature of American power is out of touch with reality. But I am making a broader, more unexpected claim, too: the United States is only at the beginning of its power. The twenty-first century will be the American century.

That assertion rests on a deeper point. For the past five hundred years, the global system has rested on the power of Atlantic Europe, the European countries that bordered on the Atlantic Ocean: Portugal, Spain, France, England, and to a lesser extent the Netherlands. These countries transformed the world, creating the first global political and economic system in human history. As we know, European power collapsed during the twentieth century, along with the European empires. This created a vacuum that was filled by the United States, the dominant power in North America, and the only great power bordering both the Atlantic and Pacific oceans. North America has assumed the place that Europe occupied for five hundred years, between Columbus’s voyage in 1492 and the fall of the Soviet Union in 1991. It has become the center of gravity of the international system.

Why? In order to understand the twenty-first century, it is important to understand the fundamental structural shifts that took place late in the twentieth century, setting the stage for a new century that will be radically different in form and substance, just as the United States is so different from Europe. My argument is not only that something extraordinary has happened but that the United States has had very little choice in it. This isn’t about policy. It is about the way in which impersonal geopolitical forces work.

EUROPE

Until the fifteenth century, humans lived in self-enclosed, sequestered worlds. Humanity did not know itself as consisting of a single fabric. The Chinese didn’t know of the Aztecs, and the Mayas didn’t know of the Zulus. The Europeans may have heard of the Japanese, but they didn’t really know them—and they certainly didn’t interact with them. The Tower of Babel had done more than make it impossible for people to speak to each other. It made civilizations oblivious to each other.

ATLANTIC EUROPE

Europeans living on the eastern rim of the Atlantic Ocean shattered the barriers between these sequestered regions and turned the world into a single entity in which all of the parts interacted with each other. What happened to Australian aborigines was intimately connected to the British relationship with Ireland and the need to find penal colonies for British prisoners overseas. What happened to Inca kings was tied to the relationship between Spain and Portugal. The imperialism of Atlantic Europe created a single world.

Atlantic Europe became the center of gravity of the global system (see previous map). What happened in Europe defined much of what happened elsewhere in the world. Other nations and regions did everything with one eye on Europe. From the sixteenth to the twentieth century hardly any part of the world escaped European influence and power. Everything, for good or evil, revolved around it. And the pivot of Europe was the North Atlantic. Whoever controlled that stretch of water controlled the highway to the world.

Europe was neither the most civilized nor the most advanced region in the world. So what made it the center? Europe really was a technical and intellectual backwater in the fifteenth century as opposed to China or the Islamic world. Why these small, out-of-the-way countries? And why did they begin their domination then and not five hundred years before or five hundred years later?

European power was about two things: money and geography. Europe depended on imports from Asia, particularly India. Pepper, for example, was not simply a cooking spice but also a meat preservative; its importation was a critical part of the European economy. Asia was filled with luxury goods that Europe needed, and would pay for, and historically Asian imports would come overland along the famous Silk Road and other routes until reaching the Mediterranean. The rise of Turkey—about which much more will be heard in the twenty-first century—closed these routes and increased the cost of imports.

European traders were desperate to find a way around the Turks. Spaniards and Portuguese—the Iberians—chose the nonmilitary alternative: they sought another route to India. The Iberians knew of only one route to India that avoided Turkey, down the length of the African coast and up into the Indian Ocean. They theorized about another route, assuming that the world was round, a route that would take them to India by going west.

This was a unique moment. At other points in history Atlantic Europe would have only fallen even deeper into backwardness and poverty. But the economic pain was real and the Turks were very dangerous, so there was pressure to do something. It was also a crucial psychological moment. The Spaniards, having just expelled the Muslims from Spain, were at the height of their barbaric hubris. Finally, the means for carrying out such exploration was at hand as well. Technology existed that, if properly used, might provide a solution to the Turkey problem.

The Iberians had a ship, the caravel, that could handle deep-sea voyages. They had an array of navigational devices, from the compass to the astrolabe. Finally they had guns, particularly cannons. All of these might have been borrowed from other cultures, but the Iberians integrated them into an effective economic and military system. They could now sail to distant places. When they arrived they were able to fight—and win. People who heard a cannon fire and saw a building explode tended to be more flexible in negotiations. When the Iberians reached their destinations, they could kick in the door and take over. Over the next several centuries, European ships, guns, and money dominated the world and created the first global system, the European Age.

Here is the irony: Europe dominated the world, but it failed to dominate itself. For five hundred years Europe tore itself apart in civil wars, and as a result there was never a European empire—there was instead a British empire, a Spanish empire, a French empire, a Portuguese empire, and so on. The European nations exhausted themselves in endless wars with each other while they invaded, subjugated, and eventually ruled much of the world.

There were many reasons for the inability of the Europeans to unite, but in the end it came down to a simple feature of geography: the English Channel. First the Spanish, then the French, and finally the Germans managed to dominate the European continent, but none of them could cross the Channel. Because no one could defeat Britain, conqueror after conqueror failed to hold Europe as a whole. Periods of peace were simply temporary truces. Europe was exhausted by the advent of World War I, in which over ten million men died—a good part of a generation. The European economy was shattered, and European confidence broken. Europe emerged as a demographic, economic, and cultural shadow of its former self. And then things got even worse.

THE FINAL BATTLE OF AN OLD AGE

The United States emerged from World War I as a global power. That power was clearly in its infancy, however. Geopolitically, the Europeans had another fight in them, and psychologically the Americans were not yet ready for a permanent place on the global stage. But two things did happen. In World War I the United States announced its presence with resounding authority. And the United States left a ticking time bomb in Europe that would guarantee America’s power after the next war. That time bomb was the Treaty of Versailles, which ended World War I—but left unresolved the core conflicts over which the war had been fought. Versailles guaranteed another round of war.

And the war did resume in 1939, twenty-one years after the last one ended. Germany again attacked first, this time conquering France in six weeks. The United States stayed out of the war for a time, but made sure that the war didn’t end in a German victory. Britain stayed in the war, and the United States kept it there with Lend-Lease. We all remember the Lend part—where the United States provided Britain with destroyers and other matériel to fight the Germans—but the Lease part is usually forgotten. The Lease part was where the British turned over almost all their naval facilities in the Western Hemisphere to the United States. Between control of those facilities and the role the U.S. Navy played in patrolling the Atlantic, the British were forced to hand the Americans the keys to the North Atlantic, which was, after all, Europe’s highway to the world.

A reasonable estimate of World War II’s cost to the world was about fifty million dead (military and civilian deaths combined). Europe had torn itself to shreds in this war, and nations were devastated. In contrast, the United States lost around half a million military dead and had almost no civilian casualties. At the end of the war, the American industrial plant was much stronger than before the war; the United States was the only combatant nation for which that was the case. No American cities were bombed (excepting Pearl Harbor), no U.S. territory was occupied (except two small islands in the Aleutians), and the United States suffered less than 1 percent of the war’s casualties.

For that price, the United States emerged from World War II not only controlling the North Atlantic but ruling all of the world’s oceans. It also occupied Western Europe, shaping the destinies of countries like France, the Netherlands, Belgium, Italy, and indeed Great Britain itself. The United States simultaneously conquered and occupied Japan, almost as an afterthought to the European campaigns.

Thus did the Europeans lose their empire—partly out of exhaustion, partly from being unable to bear the cost of holding it, and partly because the United States simply did not want them to continue to hold it. The empire melted away over the next twenty years, with only desultory resistance by the Europeans. The geopolitical reality (that could first be seen in Spain’s dilemma centuries before) had played itself out to a catastrophic finish.

Here’s a question: Was the United States’ clear emergence in 1945 as the decisive global power a brilliant Machiavellian play? The Americans achieved global preeminence at the cost of 500,000 dead, in a war where fifty million others perished. Was Franklin Roosevelt brilliantly unscrupulous, or did becoming a superpower just happen in the course of his pursuing the “four freedoms” and the UN Charter? In the end, it doesn’t matter. In geopolitics, the unintended consequences are the most important ones.

The U.S.–Soviet confrontation—known as the Cold War—was a truly global conflict. It was basically a competition over who would inherit Europe’s tattered global empire. Although there was vast military strength on both sides, the United States had an inherent advantage. The Soviet Union was enormous but essentially landlocked. America was almost as vast but had easy access to the world’s oceans. While the Soviets could not contain the Americans, the Americans could certainly contain the Soviets. And that was the American strategy: to contain and thereby strangle the Soviets. From the North Cape of Norway to Turkey to the Aleutian Islands, the United States created a massive belt of allied nations, all bordering on the Soviet Union—a belt that after 1970 included China itself. At every point where the Soviets had a port, they found themselves blocked by geography and the United States Navy.

Geopolitics has two basic competing views of geography and power. One view, held by an Englishman, Halford John Mackinder, argues that control of Eurasia means the control of the world. As he put it: “Who rules East Europe [Russian Europe] commands the Heartland. Who rules the Heartland commands the World-Island [Eurasia]. Who rules the World-Island commands the world.” This thinking dominated British strategy and, indeed, U.S. strategy in the Cold War, as it fought to contain and strangle European Russia. Another view is held by an American, Admiral Alfred Thayer Mahan, considered the greatest American geopolitical thinker. In his book The Influence of Sea Power on History, Mahan makes the counterargument to Mackinder, arguing that control of the sea equals command of the world.