Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Birlinn

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

June 1945. Hitler has triumphed, Britain is under German occupation and America cowers under the threat of nuclear attack. In the dead of night, a figure flits through the ruins of Dryburgh Abbey, searching for a hidden document he knows could change the course of history. The journal he discovers, by a young soldier, David Erskine, records an extraordinary story. When the Allies drive the Germans out of France and victory seems imminent, Erskine is in Antwerp, where he witnesses a world-changing reversal of fortune. From a high vantage point, he watches a huge mushroom cloud rise over London: an atomic bomb has been detonated by the Germans in a last desperate roll of the dice. Captor becomes captive and Erskine is held as a POW in his own land. As the brutal grip of the occupying forces tightens, he is determined to join the resistance. A daring escape leads him and his fiancée Katie on a breathless chase to the university town of St Andrews, where the Germans have established a secret research laboratory. When it becomes clear what its purpose is, David, Katie and their small, trusted band must adopt a desperate and audacious plan to thwart Nazi domination . . .

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 386

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

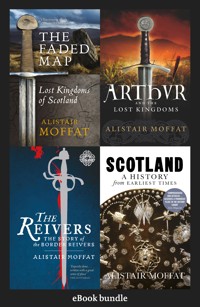

Alistair Moffat was born and bred in the Scottish Borders. He is a former Director of the Edinburgh Festival Fringe and Director of Programmes at Scottish Television, and is the founder of the Borders Book Festival. From 2011 to 2014 he was Rector of the University of St Andrews. He is the author of a number of highly acclaimed books, including Scotland: A History from Earliest Times, Britain’s DNA Journey, To the Island of Tides and The Hidden Ways. The Night Before Morning is his first work of fiction, and TV rights were acquired by actor and producer Tom Conti prior to publication.

First published in 2021 byBirlinn LimitedWest Newington House10 Newington Road EdinburghEH9 1QS

www.birlinn.co.uk

Copyright © Alistair Moffat 2021

The moral right of Alistair Moffat to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored or transmitted in any form without the express written permission of the publisher.

ISBN: 978 1 78027 737 0eBook ISBN: 978 1 78885 470 2

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication DataA catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Typeset by Initial Typesetting Services, Edinburgh

Printed and bound by Clays Ltd Elcograf S.p.A.

In memory of Jennie Erdal,whose sparkle is sorely missed

PROLOGUE

16 June 1945

Under the canopy of the trees, it was black-dark. Through the full leaf of high summer, no light could pierce the oaks and chestnuts, and the midnight path was a matter of guesswork. The man moved very slowly. Often stopping, holding his breath, listening for the rustle of movement, sometimes stretching out a hand where he thought a tree trunk might stand in his way, he made slow, hesitant progress. And yet, about a hundred yards away, he could see where he wanted to go. High, bright and full, the moon lit the night river, glinting silver off the water. But reaching it was taking much longer than he planned and he could not risk a torch.

Edging closer to the moonlit water, groping through the darkness, his feet, not his eyes, recognised exactly where he was. The last few yards of the track were paved – a memory of its ancient purpose, harking back to the time when many walked upon it, going about their daily business. Red sandstone paving led to the river’s edge because once it had been a busy ford, the Monksford. For three lazy, meandering miles the River Tweed flows through sanctity, looping around two ancient monasteries, and in the millennia before bridges, this was the place where monks had forded the great river. Now half forgotten, overgrown and used only by the occasional horse rider, the track suited his purpose perfectly.

Once the man found the wooden kayak he’d hidden earlier that day, he dragged it to the edge of the river, making as little noise as possible. The moonlight was suddenly brilliant, almost dazzling, dancing off the water’s surface as the river turned south towards his destination. Wading into the current, the man expertly steadied the kayak and sat down, rocking it slightly. Paddling quickly across to the far bank and its welcoming darkness, he allowed the current to carry him downstream and to what he hoped would be the solution to a mystery.

What John Grant had sent him was both puzzling and perplexing. At his funeral, few contemporaries gathered because the old man had outlived almost all of them. It was a sparse, quiet atmosphere in the chapel but there was one colourful emblem of the past that conjured a memory of extraordinary valour during one of the bloodiest battles in history. On the coffin lay the old soldier’s regimental Glengarry cap. Navy blue with a red toorie bobble, two long black ribbons at the back, and a red, white and black dicing trim, it bore the gleaming badge of the King’s Own Scottish Borderers. He had fought bravely at the Battle of the Somme in 1916, leading his men over the top again and again and rescuing two wounded comrades from the desolation of no man’s land.

It was the old soldier’s granddaughter who had first brought them together. At a talk on local Roman antiquities, the man had noticed her immediately, sitting in the front row: a tall, fair, classic beauty with pale, ice-blue eyes. In repose, her face seemed sad to him, etched with a memory of loss or disappointment. But when she smiled, it changed completely, and warmth flooded back. Afterwards she had made introductions, even though she did not know the man’s name. Perhaps it was only politeness with a newcomer, and maybe it was his imagination, but did she do that to discover who he was? At the time he had no idea of the part she played in what was to follow.

After that first meeting, the man had joined the history society and become friendly with John Grant. The tone was mostly formal, reticent about anything remotely personal, conversation usually confined to matters historical. But behind the politeness, there glowed an immediate but unstated warmth and great respect.

A week after the funeral, a well-sealed brown envelope arrived from a firm of local solicitors. A formal letter told the man that their client had wished him to have the enclosed papers. There was a spidery, handwritten letter clipped to a sheet carrying two verses of a poem, a series of maps and a drawing.

I know that the sort of ancient history I enjoy bores you, even though over the months we have been acquainted you have listened attentively and dutifully read my papers on Roman road building and burial practices. Through our conversations, I sense that your real interest is in politics and much more recent events. I share that interest, but while I live, I dare not give voice to my thoughts, not to anyone. The Romans lie at a safe enough distance.

We have been fed an agreed narrative about this last war, its course and its outcome. Not much of it is true, and I think you know that.

But where is the first-hand evidence for a different version of history? Where are the accounts of those who witnessed it? They need to be found and made widely known before we who lived it are all dead and dust gathers over closed chapters.

I think I know where the truth can be found, but not exactly where. For the sake of a better future, will you now try to clear away the lies and discover what really happened in the recent past and how it has indelibly shaped the present?

Much taken aback at such forthright, deeply held views, the man picked up the rest of the package. The note was paper-clipped to a copy of two verses from Sir Walter Scott’s poem, ‘The Eve of St John’.

O fear not the priest, who sleepeth to the east!

For to Dryburgh the way he has ta’en;

And there to say mass till three days do pass,

For the soul of a knight that is slayne.

The varying light deceived thy sight,

And the wild winds drown’d the name;

For the Dryburgh bells ring, and thewhite monks do sing,

For Sir Richard of Coldinghame!

In the kayak, the man paddled along gently, quietly, keeping to the safety of the shadows of the right bank. It was long past curfew and its strict rules were policed as much by curtain-twitching watchers as by the authorities. And the moon had made the landscape graphic, like a black-and-white film.

He could soon make out stands of tall hardwood trees. They bordered the policies of a grand house, now a large hotel, and beyond that lay the ruins of Dryburgh Abbey. Pulling quickly over to the left bank, the man felt the keel of his kayak scrape the bottom. Carefully, steadying himself with the paddle, he stood up, splashed into the shallows and pulled his boat under the branches of an overhanging tree.

Having scrambled up the bank and back into the darkness of the shadows under the trees, he came to a drystane dyke and stood on the edge of the abbey precinct, what had come to seem like a giant board game, a landscape of snakes and ladders.

It was clear from the Walter Scott verses and the attached maps and drawings that the old soldier had been looking for a hiding place of some kind. Quite what it might conceal was unclear. And its precise location was even more unclear. But it was here somewhere, amongst the ruins.

In the weeks since John Grant’s death and the arrival of his package, the man had come often to the abbey and begun to understand something not only of its history but also its atmosphere, a sense of otherness. He was careful always to look like a visitor and not an inquisitor. He asked no questions of the guides and carried with him none of the maps and drawings he had been sent.

But far from making progress that spring and early summer, the man’s enquiry appeared to be going backwards. On his first visit, he believed he had discovered something the old soldier had missed, something that looked very like a diagrammatic map, something that could at once solve the puzzle if it could be decoded. Crudely scratched on one of the wide foundation stones of the north wall of the abbey church was a gaming board.

To amuse himself and some of his workmates on days of rain or worse, one of the medieval masons had taken his cold chisel and mel to make a board for a game known as merelles or ‘Nine Men’s Morris’. Very ancient, originally played by Roman builders, it is a strategy game, like chess, but played on a pattern of squares – with progressively smaller ones inside a larger, and all connected by straight lines. Each player has nine counters, usually either black or white, and they take it in turns to place them on some of the twenty-four points where the straight lines and the squares intersect. Like noughts and crosses, the goal is to set three counters in a row: what is known as a ‘mill’. This allows a player to remove one of his opponent’s pieces, and the ultimate goal is to remove seven of the nine so that he could no longer form a mill of three.

The man became fascinated and in a charity shop bought an old chessboard that had the grid for merelles on the back. With draughts pieces, he played out the game’s strategies in an effort to make an arrangement that might look like a map. Perhaps a mill would point in a certain direction, or perhaps two would represent coordinates. The number three featured in Scott’s poem and the board scratched by the masons was close to the great man’s tomb. But after much frustration, countless moves, gambits and variations, the man concluded that the merelles board was of no importance, something uncovered by accident when the abbey was made ruinous by an English army in 1544. It was a curiosity, not a clue.

Over the course of his many visits, the man learned that David Erskine, the Earl of Buchan, had bought the abbey ruins in 1786. A keen antiquarian, he conserved as much as possible and planted beautiful specimen trees, rhododendra and borders of ornamental shrubs, thus converting Dryburgh into a garden. The shell of the great church and the conventual buildings became the equivalent of the follies built to fill the vistas from the drawing room windows of a grand house: a huge garden feature.

Normally a mild, well-mannered man, Walter Scott disliked Erskine intensely, writing that he was a person whose ‘immense vanity obscured, or rather eclipsed, very considerable talents’. Scott was buried at Dryburgh because of rights retained by his family, but it seemed a strange decision given the visceral dislike of the owner of the abbey. Did that dissonance have any bearing on the puzzle?

More and more, the man was drawn back to the extract from ‘The Eve of St John’. Walter Scott’s second verse began with doubt, a sense that all was not what it appeared: ‘The varying light deceived thy sight’. And so all that early summer, growing increasingly anxious that his frequent visits would be noted by the guides and the lady at the ticket office – everyone was vigilant these days – the man had varied the time of day he came to the abbey. Since he imagined that the sun’s rays might reveal something, somehow, he had always come on sunny days. Perhaps at different times, when the sun threw different shadows, something would be revealed?

But his persistence shed no new light – until he realised something so blindingly obvious, it annoyed him. A schoolboy could have worked it out. Light does not come only from the sun. Scott wrote of deceit and ‘a varying light’; perhaps a clear night with a full moon would answer all questions – if he was not seen and caught breaking curfew. The man decided that, after a month of frustration, the risk of one last effort to solve the old soldier’s puzzle was worthwhile. And so he had waited for the night of the next full moon. Tonight.

Having looked over at the façade of the hotel to reassure himself that all was quiet, and no one had dared to venture out, even for a breath of night air at the grand entrance, the man scrambled over the drystone dyke and into the abbey precinct.

It was close to midnight and the moon was climbing to its zenith. The man could see that the nave of the abbey was brightly lit, its pink sandstone almost glowing. His plan was to enter through the west door and face east towards the presbytery and the high altar to see if moonlight showed him something sunlight could not. But when he passed under the rounded arch and stood about halfway down the length of the great church, he could see nothing that looked different.

As he stood looking about him, the quiet of the still night was suddenly shattered.

Very close by and coming quickly closer, sirens screamed and the man saw headlights swing across the parkland beyond the ruins. He froze, exposed in the bright moonlight, the nearest cover thirty yards away. Willing himself not to run or make any sudden movement, he slowly sank to his knees and crawled behind the low stump of a pillar. Three cars raced into the hotel car park, ripping and spraying the gravel as they turned and stopped.

Peering over the pillar, the man saw six officers in black uniforms slam doors and run towards the main entrance of the hotel. He exhaled with relief, blowing out his cheeks. He could not stay in the open. Bending almost double, he scuttled back through the west door and hid in the shadows of a huge wellingtonia. Looking across at the hotel, he watched lights go on in the public rooms of the ground floor and then in corridors and rooms.

Moments later, four of the officers re-appeared at the entrance. Two dragged a handcuffed man, still in his pyjamas, and behind them, two more pinioned the arms of a woman in a nightdress. She yelped and stumbled as the gravel cut into her bare feet. One of the officers grabbed her hair, dragged her and almost threw her into the back of a car. Gunning their engines, sirens flashing and howling, two of the cars sped off into the night.

Soon afterwards, two more uniformed men appeared on the steps of the main entrance and shook hands with a civilian in a suit. Watching from the shadows, the man recognised an all too familiar pattern. Officers from the Department of Public Safety preferred to make arrests, usually on the basis of information received, in the middle of the night without any warning. That was when suspects were most vulnerable, most likely to confess to crimes or misdemeanours. Those who supported or reluctantly understood the necessity for this sort of policing called the officers ‘the Vigilantes’. The name came from their motto, Semper Vigilans, ‘Always Watchful’, and their style, which was redolent of those trigger-happy cowboys who sometimes took it upon themselves to act beyond the law in Westerns.

Winded by the brutality he had just witnessed, the man considered abandoning his search. He did not even know what he was looking for. This quest had become an obsession, a very dangerous preoccupation that could see him bundled into the back of a car and beaten by a bunch of Vigilantes. And yet cold logic told him that the local thugs were busy. And they had two captives to amuse themselves with.

The windows of the hotel were still lit and frightened guests would be whispering to each other, wondering what had just happened. The last thing any of them would do is venture outside after curfew. If the man was to make one last effort to find what the old soldier had been looking for, then this was probably the safest time to do it. And once nothing had been found, no hiding place uncovered, well, then he could forget about the whole thing. He had done his best, taken very considerable risks, and would have nothing to reproach himself for.

Nevertheless, it seemed prudent to put the ruins of the abbey between himself and the hotel. The Vigilantes might extract information from the terrified couple that would bring them back – and quickly. The man skirted the low wall that bordered the nave, turned right down a flight of steps through an arch and came to the entrance to the chapter house. It had survived almost intact from the depredations of the sixteenth century and there were stone seats around its edges. Leaning back against the cold stone wall and stretching out his legs, the man tried to gather his thoughts. Patting his pockets, he found a bar of chocolate and munched a few squares for a shot of energy.

His watch told him that the moon would reach its culmination in about fifteen minutes. If its rays were to show up anything then that would likely be the time. Staying close to the pillars of the chapter house doorway, the man looked around the cloister to be sure that he was alone and could not be seen from the upper storeys of the hotel. At the foot of a stair and through another arch, a path led to the gatehouse and the bridge over the water channel. Beyond it were the policies of Abbey House. It stood about three hundred yards to the south-east and was once the stately home of the antiquarian, David Erskine. Its windows were dark. In the stillness, the man could hear no movement.

And then at that moment, the heavens shifted and the world stopped still. It was as though stage machinery began to grind to produce a fleeting illusion, something that observers knew was incredible but saw clearly. A thick cloud passed over the moon and the land plunged abruptly into darkness. Such was the shock of it that the man stopped, had to steady himself and then look up at the sky. And then the wheels ground again, the heavens shifted once more, the moon was revealed, the land brilliantly lit and the old soldier’s puzzle was suddenly solved.

No more than a hundred yards away, hidden by trees until that moment, stood a small circular building with a conical roof. And on the point of the cone there shone a tiny moon, an earthly reflection of the astronomical body above. It seemed to radiate a light of its own. But as the man moved closer, magnetically attracted, as if he saw that it was a steel ball of some kind. Burnished to a brilliant sheen, it absorbed the milky light of the moon and appeared to have its own aura.

There was a low wooden door on the far side of the building, hidden from the big house. Captivated and made bold by the otherworldly moment, the man did not hesitate, or trouble to look around or care about the noise when he shouldered the door open. In the musty blackness, he put on his head torch and looked inside. There was nothing. The little building was empty, completely empty; there were no chests or containers of any sort on the paved floor. Not rounded like the outside, the walls were squared, making a box-like interior. There was nothing at all to be seen.

The man raked his torch beam up and down the walls. They were not flush but covered with square stone boxes about a foot across. He had broken into an old dovecote and these were nesting boxes for pigeons, although no pigeons nested and nothing seemed to have been left or hidden anywhere. Nonetheless, the man felt sure that Walter Scott’s ‘varying light’ had led him to the right place. He stood in the middle of the paved floor staring at the stone squares and, very slowly, almost without thinking, he realised that they were not only nesting boxes. They were also something else.

He was staring at a giant merelles board.

On one wall, twenty-four boxes imitated the twenty-four points on a board, and he could see two mills. Three small round stones had been placed in one row of boxes that were horizontal, and in another three was a mill of three more round stones that ran vertically. He could see that they were arranged as coordinates. The mills almost met in the middle of the wall of boxes. Almost. Both pointed at a nesting box that had been closed, made blank. A stone square had been fitted over the box.

The man could reach up and touch it but he was not tall enough to shift the square piece of stone. Climbing, using the lower boxes as footholds, he managed to squeeze his fingers into a tiny gap on one side. But the piece of stone would not shift. Tearing his fingernails, he could not pull it out. His chest heaving, sweat running down his face, he tugged and scraped at the edges, but there was not even the slightest movement. The cover seemed to be fitted flush. Tiring, and grunting with effort, the man tried to climb up a little higher to get more purchase, but he lost his footing, grabbed at anything – and accidentally pushed at the little stone square. It fell inwards.

The man lifted up its edge and slid it out. Feeling with his hands in the nesting box, he pulled down a package, something wrapped in an oilskin. Inside was a thick, weathered and battered leather-bound notebook. That was all there was. The man managed to climb a little higher and shone his torch into the nesting box but there was nothing else to be found.

Riffling quickly through its thin pages, he saw that he had found not a printed book but hundreds of pages of small but clear handwriting. It seemed to be a diary or a journal of some kind. Brushing off the dust and the cobwebs, the man opened the notebook and read the first lines on the first page.

This journal is the property of Captain David Erskineof the 1st Battalion, King’s Own Scottish Borderers.If you have retrived it, that means he is a dead man.

I

What you have in your hands is, for the most part, an account of history in the old sense. For the Greeks who invented it – Herodotus, Thucydides and the others – the word histor meant ‘witness’; what witnesses saw with their own eyes and reported that was history. Much of what you will read, I saw and was witness to.

Too disorganised and episodic for a diary, what follows is more like a journal, a record of what I remembered and wrote down, sometimes at the time, sometimes later. I have also occasionally added material about events that took place elsewhere and I did not witness, as they help explain how and why things occurred as they did. Especially when events began to accelerate, running far beyond my ability to record them directly, I have had to rely on my imagination. But I have invented nothing. Instead, I have used my knowledge and understanding of how our enemies thought and acted to give context to the awful incidents I did witness. And I have included my own versions of what others – particularly one who is very dear to me – told me of their experiences at the time.

Everything I did, I did for the best as I understood it, and of course I made terrible mistakes and calamitous misjudgements. My actions sometimes caused heart-breaking sadness and I will carry the guilt and regret for those to my grave. But I tried to act in the best interests of my country, more particularly in the interests of the best of my country. God knows, others behaved wickedly and brought down shame on all our heads.

What you have here is a true record of a most momentous time, a period when the world was changed utterly.

Through bright and dark times, I kept in mind lines from Walter Scott. He is buried with my kinsmen in our ancestral place and even though he wrote spitefully about my people, he captured the wellspring of why I did all that I did as the world hurtled towards the edge of an abyss.

Breathes there the man, with soul so dead,

Who never to himself hath said,

This is my own, my native land!

Addendum – 28 March 1945

You are about to read a copy of the original journal. It was made soon after the events it describes, when memories were fresh. The copyist has included their own accounts of events the primary writer knew very little of. In particular, the copyist made a journey into the Cheviot Hills to discover the fate of someone whose role was pivotal to all that happened and to listen to a remarkable story.

II

6 June 1944

Rum, vomit and fear, all soaked by salt spray. As the flat-bottomed landing craft whumped down on the choppy seas of the Channel, sometimes yawing from side to side, men retched, soiling their clothes, smearing sick over the packs of those in front of them. Some, even though their throats were raw from dry heaving, took a swig of fiery, sickly sweet rum as the canteen was passed around. Some men vomited into their helmets and let the continuous spray rinse them.

Holding tight onto a bow rail, I forced myself to look ahead fixedly, determined not to throw up. This was bad enough, but God knows what we would face when the landing craft finally stopped throwing us around and the ramp went down at 07.25.

Fear makes a mockery of us all, voiding our bowels as well as our stomachs, making our hands shake and our hearts race. But the truth is that fear keeps us alive. It makes us react, incites us to retaliate, to lash out, to be violent and to kill.

Earlier, when the sergeants assembled the three platoons on the deck of the transport ship, waiting for the order to embark on the landing craft, I shouted for the men to gather round for some brief words I had rehearsed many times in the previous twenty-four hours. A senior officer had firmly advised me to keep it brief and not to try to rouse emotions. The Borderers were all regular soldiers, and some had been under intense fire on French beaches before, at Dunkirk. Nevertheless, I sensed that they looked to me, of all people, for reassurance – of any sort. What I said was banal. On the page, it even looks dull, uninspired, not fitting for the moment. But on that night before that morning, nothing could be banal, all was heightened.

‘Borderers!’ I said, fighting to keep my voice steady. ‘In a short time the ramp will go down and we’ll face the enemy. Reconnaissance tells us that we’ll see a beach at low tide, a sea-wall, a road behind it and a row of houses on the other side. At all costs, we must get off the beach as soon as we can. Go forward. Do not stop. Take the fight to the enemy. God speed, and God protect the Borderers!’

The truth was that I believed in neither God nor my ability to lead these soldiers to victory, safety or even survival. I had been given my commission not for any military merit but because I could speak German fluently and had been in the officer training corps at my university. And also, I suspect, on account of my family and its history. Titles carry obligations as well as privileges, as well as the baseless assumption of an inherited ability to lead men.

As the ceaseless spray washed over the landing craft and men retched as it slapped down on the sea after each swell, my hands were shaking and my head spinning. God knows what we were about to face. I prayed that such courage as I had would not fail me, my legs would move and I would not dishonour my name.

*

Nothing, I suspect, had prepared even the most experienced regular soldiers and officers for the sights that greeted them on embarkation at Southampton the night before. The 1st Battalion, King’s Own Scottish Borderers boarded one of more than five thousand ships about to set sail from the Channel ports to rendezvous in a sector south of the Isle of Wight. It was an astonishing armada, but one travelling in the opposite direction from the Spanish. On every side the sea was studded with dark, looming shapes: huge battleships, the Warspite, Ramillies and others; many cruisers; even more destroyers, minesweepers, transport ships and craft I could not identify. Armed, waiting, hoping against hope, more than one hundred and fifty thousand men were being carried by this armada to attack the Normandy coast. Surely it was enough? Surely sheer numbers and firepower would overwhelm the German defences. As we steamed southwards, the edging light on the eastern horizon picked out smoking funnels, masts and the spiky outline of batteries of great guns. It was a belly-hollowing sight.

But most of all on that night voyage, I remember the pipes. Cutting through the hum of the engines of the ships and the wash of the choppy sea, I could distinctly hear bagpipes playing and immediately recognised ‘The Road to the Isles’. Its familiar lines – ‘the far Cuillin are putting love on me’, or ‘by Tummel and Loch Rannoch’ and ‘the tangle o’ the Isles’ – rang round and round my head. The Borderers cheered, glad to have something to distract them. It was not a war rant, but a march of sorts, one that crossed another sea, and its jaunty melody somehow sent us into battle in better spirits. Later, I learned that Simon Fraser, Lord Lovat, had asked his piper, Bill Millin, to play, telling him that the Scots ought to lead the invasion of Hitler’s Europe. Other ships heard the skirl of the pipes and captains ordered more music to be played over the tannoys as the armada steamed through the fateful night.

When their commando landing craft reached its beach, Lovat apparently asked Millin to play ‘Highland Laddie’ and ‘All the Blue Bonnets Are Over the Border’. Crazy, but somehow the music seemed to dissipate the terror around the men. A German prisoner of war taken that day said they did not take aim at Millin as he marched up and down the beach, his drones and their tartan trim an easy target, because they thought him a madman. An extraordinary image as war raged around the lone piper.

From the transport ship I had seen a pale dawn rising, no sun but streaks of light blue on the eastern horizon. Above us, squadrons of Lancasters and other planes I did not recognise droned towards the French coast and in moments we saw flashes as their bombs burst over the land. It was encouraging. Perhaps we would find the German defences pulverised, soldiers emerging from the rubble with their hands in the air, ready to surrender. From that moment, time began to accelerate so quickly that I did everything without thinking, relying only on instinct.

The ship’s tannoy crackled: ‘Prepare to man your boats.’ There was no turning back now.

My three platoons had to climb down the sides of the ships using scramble nets in the subdued morning light. The sea was so rough that the landing craft bobbed up and down alarmingly, and despite the efforts of the crew, the swell opened up gaps between it and the transport ship, or the two clanked as they collided. It was very dangerous. Some men carried more equipment than others and my radio operator, Mallen, had great trouble. But enough of us had made the descent to be able to pull the scramble net tight against the landing craft. We bundled Mallen down, although he yelped when he cracked his elbows on the metal deck.

Twenty-four hours before, the briefing had identified our objective as Queen Beach, near the small seaside town of Ouistreham, not far from Caen. Air reconnaissance had shown defences, pillboxes and artillery batteries behind a long sea wall. It would be vital to reach it, get over it, get across the road and get behind the defensive line. The plan was for amphibious tanks to land first, attack and attract fire, and before that bombers would attempt to make craters for infantry cover. But the two hundred yards of the beach below the wall looked to me like the perfect killing field. To say nothing of wading agonisingly slowly through the sea before it was reached.

Three regiments each supplied a battalion in the first wave: the Borderers, the Royal Ulster Rifles and the Lincolnshire Regiment. Scotland, Ireland and England. For completeness, we should have been joined by the Royal Welch Fusiliers.

Despite the choppy sea, the crews of the landing craft managed to get us all in formation so that we would reach the beach at approximately the same time, 07.25. A staggered series of landings would have been disastrous, allowing the defenders to concentrate their fire on each craft in turn. But before we could move forward together, thunder boomed and fire rent the sky. The naval bombardment began. It was deafening, as though the heavens were exploding. Behind us, the Warspite and the Ramillies fired their huge guns and the shells shot over our heads like express trains racing out of a tunnel.

My chest seemed to tighten and the pressure waves pushed hard on our landing craft as salvoes from the battleships, cruisers and destroyers made the great ships recoil. The roar and the flashes should have made us cheer, but in truth the overwhelming instinct was to cower and flinch and hope none of the shells dropped short.

When the guns were finally silenced, it was like a signal. Now it was our turn. The formation of landing craft moved forward like a monstrous metal tide. We were carried into the eye of a gathering storm, one that would burst on us in moments.

*

I looked over the edge of the forward ramp and it seemed in the eerie, grey stillness that the winds of the world swirled around us. When we reached the shallow water of the foreshore, the ramp would be let down and I would lead my men into the killing field. In all my life, I had never felt such hollow loneliness.

I was jolted back into the moment by Sergeant Taylor shouting in my ear, ‘Thirty minutes to landing, sir!’

I turned and nodded.

‘You’ll be all right, sir,’ he added with a tight, grim smile.

That flash of kindness told me we would fight for our country and against a manifest evil, certainly, but most of all, we would fight for each other. We were a band of Borderers, and perhaps brothers too.

Maddened by fear, by finding themselves in the jaws of hell, skeins of sea birds flew low and very fast just above the surface, like tracer fire. God knows what carnage was happening on the farms inland, with animals running in blind panic as shells exploded and bombs tore craters out of the fields.

As we moved closer, I could see that the Ulsters on our left were holding formation. And then a moment later I felt the shock of finding we were in range, as a rattle of metallic pings tinged off the sides of the landing craft. A hail of what must have been machine guns bullets hit us. I could hear them whipping through the air. In an instant reflex, we all cowered down below the hull. The moment we let down the ramp, we would be fired on. We were in their sights.

‘Be ready,’ I roared to Sergeant Taylor, ‘to give the order to disembark!’

My watch had 07.25 precisely. I risked looking to my right to the line of Borderers’ landing craft and then left to the Ulsters’. They had all halted or were slowing but none had let down their ramps. Why the moment of hesitation? A sense of ‘you first’? Were they waiting for one craft to charge the beach and attract fire before giving the order to disembark? Surely not.

We were not now under fire. Now was the time to go, whatever any other commander decided. On the beach I saw two disabled and abandoned amphibious tanks. Had there been a successful landing? Had some broken through? Where?

The Ulsters’ ramp inched forward, and I shouted, ‘Now!’

Grinding, cranking down through what sounded like rusty gears, the ramp splashed into the water. Grabbing the handrail, losing my slippery footing, almost falling as the craft suddenly shifted, I scrambled down. The shock of the water sharpened my senses even more. Up to my waist, it made me pump my legs and move. The Borderers followed.

I turned to Sergeant Taylor and, as he opened his mouth to speak, he was hit in the face. He toppled forward, instantly dead, knocked me down and saved my life. Others pulled at the straps of my pack and I spluttered upright and waded ashore, soaked, breathless with shock.

Enemy fire was sporadic. Thoughts flickered. Perhaps they were too few to direct their guns at every landing craft at once. But they clearly had snipers, perhaps in the tall houses I could see, picking off the first down the ramps, those men moving so, so slowly through the water. And one of them had missed me and killed my sergeant.

Now on wet sand, I ran, half falling as it gave way under my boots, and made for the sanctuary of an abandoned tank. Taking cover behind it were half a dozen other Borderers. At that moment, a landing craft behind us was hit by a shell, killing and maiming many, buckling the hull. Clearly the Germans had wheeled artillery into their defensive line, and the tank was a big target; we had to move, get off the beach. Ahead of us, out in the open, a young recruit, clearly terrified, was digging feverishly with his entrenching tool. He made me move. Roaring for them to gather round me, I ran out with my men from behind the tank, a spray of machine gun fire throwing up sand in front of me, and I grabbed the at the boy’s pack and dragged him behind me. We were forty yards from the sea wall and safety.

‘Run! Run! Now!’ Screaming at my men, we sprinted, pushing at the loose sand with our boots.

The young soldier scurried like a crab behind me. And was shot dead, by the snap of a single report. Another sniper kill. I began to think myself lucky. Or next.

We hunkered down behind the sea wall, chests heaving, safe for the moment. The respite gave me the chance to turn and see what was happening behind us. Many had not been lucky. A tide of blood streaked the white foam of the foreshore. Wounded men called out pitifully. Some were still behind the abandoned tanks; they needed to get off the beach. But below the sea wall, I could see most of my men. Maybe thirty had made it. They crouched, holding fast to their rifles, looking at me.

About a hundred yards to my left was a gap in the wall where a concrete ramp led down to the beach. If the amphibious tanks had advanced, that was the only way they could have gone. If. If they had trundled up the ramp, we should follow because they might have used their 75mm guns to clear a path through the pillboxes and trenches strung out along the road. My watch said 08.00. We had been on the beach long enough. I decided to take Corporal Lauder, to act as a runner. He had played rugby in the Border League, was agile and quick, and he could take back orders to the waiting men.

Still roaring over our heads, the naval bombardment was directed further inland, or so I hoped. When Lauder and I reached the concrete ramp, we crawled on our bellies up to the level of the road. In each direction, we could clearly see fire spitting from gun emplacements, pillboxes and the upper floors of the tall seaside houses. For some reason, I remember the brightly painted shutters folded back on each side of the windows.

Further along, I saw the smoke of artillery fire. Wherever the Lancasters had dropped their bombs, it was not here. But directly in front of us, between two houses that had been badly damaged by shelling, there was a trail of destruction, where tanks had flattened fences and struck inland.

Don’t stop and think. Think when you have stopped. Without realising that I had learned it, that was the visceral lesson of an extraordinary morning on Queen Beach. Moving targets are harder to hit and if I could only keep my men moving forward, the picture would change constantly, forcing the Germans to turn, to look for us, to throw up barriers, move back from prepared positions. So long as we could keep moving, I felt sure confusion would be our friend as well as our enemy. We were in a strange land and the Germans knew it well. But we were running with the tide of history. Surely we were.

With two other units of Borderers joining us, we moved inland, the map telling me we were about half a mile west of Ouistreham. We exchanged fire with retreating defenders who knew and used the landscape to make their escape. Having set up a perimeter around a battered, badly shelled and deserted farm steading, we needed to contact brigade headquarters, wherever they were, for fresh orders. Now what? Our mission was to push on and take the city of Caen, about eight miles to the south. But we needed more than infantry: tanks, more firepower, greater numbers and clear leadership amidst the confusion were all essential.

The radio crackled into life and Private Mallen pressed his fingertips on the earphones, trying to find the right wavelength amongst all the deafening noise and the static. ‘That’s brigade, sir,’ said Mallen, handing me the headphones.

I could hear only part of what Colonel Murray said but gathered enough to know that we were to rendezvous at 18.00, north of the village of Hermanville.

‘Must mean the Germans have it.’ Mallen smiled. ‘The Hermans.’

Not very funny, but a break, a jolt, a different train of thought.

We pressed on. The naval bombardment had been pitiless. We saw many dead cows and horses, but it was the awful, elemental bellowing of those that had been savagely wounded that haunted our steps. I shall never forget catching sight of a horse with most of its hindquarters blown away, an awful mess of blood and bone. Shrieking in agony, it was pulling itself forward with its forelegs, trying to run away from the pain. Corporal Lauder reprimanded men who spent bullets ending the suffering of wounded animals, but I told him to leave it.

Before death had come screaming out of the skies, this had been dairying country. Small, lush fields were enclosed by ancient, high hedging and their peace had been shattered as bombs blew open ragged craters and dense blackthorn and juniper were smashed down by advancing tanks. Idyllic though this place must once have been, it was also dangerous. Known as bocage, it was perfect for ambush.

I have no memory of falling. Only of coming round, dizzy and choking.

The back rim of my helmet had hit the ground so hard after I somersaulted that the chinstrap was choking me, only freeing when I rolled on my side. I had no idea if I had been hit, no pain, no feeling in my limbs or torso except a floppy disarticulation.

Lauder’s face loomed over me. ‘Mortars, sir,’ he shouted, inches from my ear, his voice echoing down a long tunnel. ‘We need to get off the road.’

I realised I was lying on my revolver, and I was glad I could feel it jabbing into my side. My rifle lay a few feet away and I tried to roll onto all fours but collapsed slowly sideways. Lauder dragged me into a ditch choked with briar and willowherb. From a long, long way away, I heard, ‘You’re not hit, sir,’ and darkness closed over me.

Very badly concussed, or worse, the pain in my neck excruciating and overwhelmed with nausea, I came to at the sound of engines. No more than a few feet from where I lay, I saw the wheels of vehicles passing slowly. Time seemed to collapse on itself and light at first faded and then brightened. When Lauder broke into my nightmares, arriving with stretcher-bearers, I realised that many had had marched past me thinking I was a goner, another casualty of a bocage ambush.

*

Like church spires rising above the fog, my recollections of the following few days are sparse, seen fleetingly, only sharp impressions. My left side was at first numb and I pissed myself more than once. But once feeling returned, I could stand, unsteadily at first, rocking on the balls of my feet, and then I could walk.