Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Birlinn

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

The Holy Grail, the kingdom of Camelot, The Knights of the Round Table and the magical sword Excalibur are all key ingredients of the legends surrounding King Arthur. But who was he really, where did he come from, and how much of what we read about him in stories that date back to the Dark Ages is true? So far historians have failed to show that King Arthur really existed at all, for a good reason - they have been looking in the wrong place. In this fascinating and thought-provoking book, Alistair Moffat shatters all existing assumptions about Britain's most enigmatic hero. With reference to literary sources and historical documents, to archaeology and the ancient names of rivers, hills and forts, he strips away a thousand years of myth to unveil the real King Arthur. And in doing so he solves one of the greatest riddles of them all - the site of Camelot itself.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 494

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2012

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

‘The text is packed with fascinating clues to life in the Celtic past gleaned from traditional cultural practices and changing place names. His new “common-sense” deductions are combined with succinct coverage of the documentary and archaeological evidence. Those who have read other books on Arthur will find a new dimension here. Readers new to the subject should find that the book provides a vivid and thought-provoking case for the Scots’

Birmingham Evening Mail

‘Adding flesh to conjectures is an enjoyable thing to do and Moffat adds more flesh than most’

Glasgow Herald

‘[Alistair Moffat’s] book, guaranteed to get up many noses, is to be recommended’

Spectator

‘Fascinating … It is great fun and a worthy addition to the enormous canon of Arthuriana’

Daily Post (Wales)

‘This book is a virtuoso performance, packing in an astonishing amount of information on a wide range of subjects. I found his description of the British-speaking Celts of his part of Scotland, their customs and beliefs, entirely convincing. And he manages to bring them to life more vividly than any author I can remember’

Cardiff Western Mail

Alistair Moffat was born and bred in the Scottish Borders. A former Director of the Edinburgh Festival Fringe and Director of Programmes at Scottish Television, he now runs the Borders and Lennoxlove book festivals as well as a production company based near Selkirk. He is also author of a number of best-selling books. In 2011 he was elected Rector of St Andrews University.

This ebook edition published in 2012 by Birlinn Limited West Newington House Newington Road Edinburgh EH9 1QSwww.birlinn.co.uk

This edition first published in 2012 by Birlinn Limited First published in 1999 by Weidenfeld and Nicolson

Copyright © Alistair Moffat 1999 and 2012

The moral right of Alistair Moffat to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored or transmitted in any form without the express written permission of the publisher.

ebook ISBN: 978-0-85790-226-9 ISBN: 978-1-78027-079-1

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

CONTENTS

List of illustrations

List of maps

Acknowledgements

1 ANOTHER RIVER

2 AN ACCIDENTAL HISTORY

3 THE NAMES OF MEMORY

4 THE HORSEMEN

5 THE ENDS OF EMPIRE

6 AFTER ROME

7 THE KINGDOMS OF THE MIGHTY

8 PART SEEN, PART IMAGINED

9 THE MEN OF THE GREAT WOOD

10 THE GENERALS

11 FINDING ARTHUR

12 THE HORSE FORT

13 THE LANDS OF AIR AND DARKNESS

Bibliography

Index

ILLUSTRATIONS

The site of the lost city of Roxburgh

Part of an old wall which ran between the Dark Ages fort and the River Tweed

The Marchmound from the east

The Marchmound from the west

The castlemount from the south, with the River Teviot

An aerial survey of the Roxburgh site

Calchvyndd seen from across the River Tweed

The ruins of Kelso Abbey

The Trimontium Stone

Eildon Hill North

Scott’s View of the three Eildon Hills

The Yarrow Stone

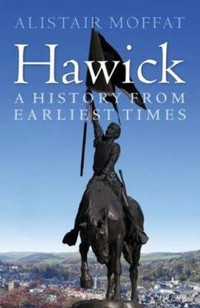

The Hawick Horse: ‘Teribus Ye Teriodin’

The aerial survey of the Roxburgh site is reproduced by permission of HMSO. The other photographs are by Ken MacGregor.

MAPS

Britain circa AD 150

Arthurian Britain

The Scottish Borders

Eildon Hill North and its environs

Yarrow, the Warrior’s Rest and Annan Street

Kelso, the Abbey and Roxburgh Castle

LINE DRAWINGS

The Yarrow Stone

Trimontium

Roman cavalry helmet

Roman cavalry visor

Roman cavalry trooper wielding a spatha

Roman cavalry trooper with a contus

The draconarius

A Gododdin warrior

Ogham script

Arthur’s cavalry wait in ambush

Medieval Roxburgh and its castle

Marchidun circa AD 500

The site of the lost city of Roxburgh is now used for point-to-point horse racing and the jumps and pavilions are from a recent meeting. Behind them is the low plateau on which the city stood, and to its left is the castlemount.

Beneath the roots of this old chestnut tree lie the ruins of a substantial wall which begins to run towards the River Tweed to the left. The line of the wall is cut abruptly by the line of the modern Selkirk to Kelso road, which is embanked by a course of large dressed stones. These stones may be the remainder of the defensive ramparts thrown up by Arthur’s predecessors from the stronghold of Marchidun down to the river. The steep slopes of the fortress mound rise only ten yards from the right of the picture.

This is from the eastern end of the Marchmound and it shows a single fragment of medieval masonry on top of the ditched mound of the Dark Ages fort. The modern road runs to the right, cutting off a second defensive ditch on its down slope.

From the western end this offers a powerful sense of how massive the mound is, and how the labour of thousands of man-hours has improved on what geology created. The River Teviot is glimpsed to the right, and the Tweed to the left.

The castlemount seen from the south, with the River Teviot defending its flank. The run of the medieval walls can be seen to the left, while the site of the old city lies a hundred yards or so off to the right. The depth and width of the river, photographed in March, shows what a formidable obstacle it was, both to attackers and for horses kept out on the haughland in the winter, out of the campaigning season.

An aerial survey of the Roxburgh site.

Calchvyndd in the winter sunshine. The old chalk hill is hidden now by the terraced gardens of the large houses on its top and obscured in summer by the trees on the river island in the foreground. The Tweed is wide and deep here as it joins the Teviot at the Junction Pool.

The massive ruins of Kelso Abbey seen from the modern town.

The Trimontium Stone commemorates the complex of Roman military and civic sites which once stood in the lee of Eildon Hill North, whose flat summit dominates the area.

Taken near the time of the feast of Imbolc, in early March, this photograph shows Eildon Hill North in its setting of fertile farmland.

This is marked on the map as Scott’s View since the sight of the three Eildon Hills watching over his beloved Borderland moved Sir Walter Scott to write so much about his native place. It is said that when his horses drew Scott’s funeral carriage past the View, they stopped out of ancient habit. I hope that is true.

The Yarrow Stone, set on a hillside above the site of the Battle of the Wood of Celidon. The trees are mostly gone now, but the inscription on the stone remembers the clash of war in that place 1500 years ago.

The Hawick Horse. With its triumphant Border warrior bearing a raided English flag, it carries the enigmatic town motto, ‘Teribus Ye Teriodin’. Or ‘Tir Y Bas, Y Tir Y Odin’ – ‘The Land of Death, and the Land of Odin’, a long echo of the Ride of the Dead.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This book has been forming for so long in my mind that it is difficult to remember some of the early kindnesses shown by people whose knowledge far outran my own. But I cannot forget how important my father, Jack Moffat, was in developing my own interest in the history of the Scottish Border country and in particular in place names. As much for his own amusement as anything didactic, he used to muse on names out loud, turning them over and over to get at what they meant. In every sense he made me think about these things before I passed them by. I owe him a debt of love that I can only repay to his grandchildren, and this book is dedicated to them.

Walter Elliot is a kenspeckle figure whose visceral and intellectual knowledge of the Borders is encyclopaedic. By an entirely different route he arrived at precisely the same conclusion as I did, and I am grateful for his kindness in sharing what he knows, and for reading this manuscript. He thoughtfully corrected some blunders but any inaccuracies that remain are entirely my own.

David Godwin should have been a farmer such is his ability to distinguish wheat from chaff. For his good humour, kindness and enthusiasm I am very grateful. Benjamin Buchan edited this book with tact and a sure touch, while Anthony Cheetham published it with brio and no little bravery.

No one helped me more in the process of writing this than Eileen Hunter. She showed me a path through the wilderness of word processing and made my life much easier. And as I navigated through options, files, tools and the rest, she kept me on the straight and narrow more than a few times. Many thanks and much love, Eileen.

My old friend George Rosie has borne several monologues on car journeys from Glasgow to Edinburgh with great fortitude, and his excellent film Men of the North for S4C and Scottish Television was partly a product of conversations on the M8.

To my Welsh-speaking friends I owe thanks for honest answers to puzzling questions and to Iain Taylor and Rhoda Macdonald more gratitude for wisdom and guidance in Gaelic. I hope none of them wince when they see passages from their beautiful mother-tongues rendered down into mine.

Harriet Buckley drew the illustrations for this book with patience and skill and also according to my suggestions. Therefore all that is good-looking about her drawings redounds to Harriet’s credit and any mistakes originate with me. Ken MacGregor is an accomplished documentary film-maker as well as an excellent photographer, and several of his pictures are worth more than several thousands of my words.

Finally I want to acknowledge the tolerance of my family. I am glad that while I was writing this my wife Lindsay, and our children Adam, Helen and Beth, had other lives which they allowed me to visit when it suited me.

Alistair Moffat

Selkirk, 1999

To Adam, Helen and Beth with all my love

Britain circa AD 150

Arthurian Britain

1

ANOTHER RIVER

This is a story of Britain; a tale of the events and circumstances that first defined Britishness, resisted homogeneity and made these islands a collection of nations whose languages have survived to describe several versions of our present, and remember a past different from the one we think we know. It is also the story of a time when written memory fails us and when archaeology is imprecise; what historians have called our Dark Ages.

This is the story of Arthur; perhaps the most famous story we tell ourselves, certainly the most mysterious and least historical. He was a heroic figure who cast a mighty shadow over our history, colouring our sense of ourselves more deeply than any other. And yet he is elusive, barely recorded on paper or vellum and certainly not noted in the chronicles of his enemies, those who eventually won the War for Britain. But Arthur touched the landscape, and it remembered him.

That is where I came across his story, in the hills and valleys of Britain. At first I did not realize what I was looking at. When I began thinking seriously about this book, what I had in mind was something quite different. Originally I intended a miniature. Richly decorated, vividly coloured, pungent and full of interest perhaps, but a miniature for all that.

I was born and brought up in Kelso, a small town in the Scottish Border country and, quite simply, I wanted to write a history of the place because it will always mean home for me and the sight of it still warms me even after thirty years of absence. I had no ambition past capturing something of the essence of Kelso by setting down in reasonable order a chronicle of the years of its existence.

But almost as soon as I began my research, a series of unexpected and puzzling questions threatened to detour my straightforward purpose. Kelso first comes on written record in 1128 when monastic clerks drew up the abbey’s foundation charter. All of the villages, churches and farms detailed in the document must have been going concerns well before that date, and so I set about finding earlier references to the town and its hinterland. Scottish medieval records are notoriously scant but I was still surprised at the paucity of material. I could find only one mention of Kelso before 1128 in any sort of document at all. This was an English translation of a poem written in Edinburgh around 600. Not in Gaelic as you might ignorantly expect, or Latin, but in an ancient form of Welsh. Known as ‘The Gododdin’1 it tells the story of the warriors of King Mynyddawg and their disastrous expedition to fight the Angles at Catterick in North Yorkshire. One of the Gododdin princes is named as Catrawt of Calchvyndd. I realized immediately that this is the oldest name for Kelso and also its derivation. In Old Welsh, Calchvyndd means ‘chalky height’ and not only is part of the town built on such an outcrop but the street leading to it bears a translation, the Scots name Chalkheugh Terrace. And in the 1128 charter Kelso is spelled Calchou. Calchvyndd and Kelso are clearly the same place.

But I found myself more than surprised to read the early history of the south of Scotland in Welsh, and more, to read of Welsh- speaking princes, kings and kingdoms in a place I thought I knew well. Who were these people? Where were these lost kingdoms? It seemed to me that there was another river running.

Catrawt and his Calchvyndd led me to ask many questions, but in particular he suggested place-names as a rich source for the early history of Kelso and the Scottish Borders. What I found gradually revealed to me was something remarkable: a story of Britain and, more, the historical truth of the most famous secular story in the world, what people miscall the Legend of King Arthur. Neither a legend nor a king, I found him remembered by the land, in the fields, Xrivers and hills of southern Scotland, and by extension by the people who farmed, knew and named where they lived. Unremarked by history, little people who walked and worked their lives for generations under Border skies. And also by looking hard at a small place I began to become aware of a much larger picture until, after a time, I could lift up a map of the Border country and see clearly the watermark of Arthur.

Before I go on to the meat of what I have found, I should make some confessions and assertions. As a historian I am an amateur, in the old sense of loving it, and emphatically not in the new sense of being sloppy or less than serious. I am certainly not an academic historian, not time-served and with no folio of published papers to act as pencil sketches for the big picture. Anyway, what academic would want to do something so literally amateurish as to write the history of his home town?2 Aside from a decent education, I only have two claims to bring to the reader’s attention. The first is simple: since no one asked me to do this, I am not obliged to be anything other than my own man. I care nothing for academic reputation, the conventional wisdom or the weight of opinion. These researches are founded on common sense and sufficient erudition.

My second claim will take longer to unpack. It directly concerns my interest in the names of places, more properly toponymy, and how my knowledge of all this began.

When I was a little boy in the 1950s my dad took me with him in his van to summer jobs. He was an electrician who worked on Saturday mornings, often going out to the grand houses of the Borders to fit a plug on a kettle or replace a lightbulb for ancient aristocrats with servants still suspicious of electricity. The toffs, as he labelled them, did not interest him much but my dad was fascinated by their land and their ability to hang on to it and shape it to their purposes. One Saturday he took me to a place called the Hundy Mundy Tower. Standing in the dank wood almost completely hidden, it was a chilly, creepy building resembling the gable end of a Gothic cathedral. My dad explained that it was a folly designed to finish a vista from the windows of a big house. The trees had been planted to add mystery and spurious antiquity. ‘Power,’ he said to me many years later, ‘that is real power; being able to alter the landscape to suit one man’s idea of a good view and invent a bit of history forbye.’

My dad knew the land around Kelso intimately and we talked a great deal about change, how it could obliterate history and how often the names of their places were all that remained of peoples who had long vanished into the darkness of the past. As he grew older and frail, I realized that much of his sort of understanding of the Borders would be obliterated too. Therefore I made extensive tape recordings with my dad and in rereading the typescript of this book I can hear the echo of his insistent voice clearly. No one else can, only me.

One more word before I set out my narrative. Much to the distaste, no doubt, of proper historians this piece of work is occasionally conveyed in the first person, not objective but nominative. In fact it is precisely names that make it so. I am a Moffat, first from western Berwickshire, earlier from Dumfriesshire. My mother’s people are Irvines, Murrays and Renwicks from Hawick and the hill country to the west. All ancient Border families, people who stayed where they found themselves and found where they stayed to be beautiful. We have been here for millennia but, apart from playing rugby for Scotland, none of my family has gained great wealth, fame or notoriety. We have acquired few airs or graces. There is no need. We are all Borderers, and that is more than enough.

And that is precisely my claim. The landscape of the Scottish Border country is part of me, I know it in my soul. The red earth of Berwickshire is grained in my hands, the rain-fed fields of the Tweed valley nourished me and the hills and forests of Selkirk fill my eye. I know this place.

2

AN ACCIDENTAL HISTORY

Since this book began its life as a series of accidental discoveries, I should begin by describing the sequence of events that forced me to draw such an unlooked-for conclusion.

Despite my frequent puzzlements and pauses I completed my history of Kelso in 1985. I remember an excellent party, some daft speeches and a hilarious dinner with my mum and dad pleased as punch that I had dedicated the book to them. Because it was the name used by ordinary people I called it Kelsae and then below it for those who wanted a Sunday name: A History of Kelso from the Earliest Times. Except it wasn’t. The earliest it got was 1113 when the future King David I of Scotland planted a settlement of austere French monks from Tiron first at Selkirk and then, moving them downriver in 1128, at Kelso. Being literate and careful men, they set down all the gifts given by David in a long foundation charter.3 While the document is rich in detail, overflows with place-names, descriptions of natural features and much monkish precision, it was none the less frustrating to have to begin the history of such an ancient place as late as 1113. Particularly since the quarry I mined for material contained nuggets of information (much of which I failed completely to understand at first) about the lost centuries before the monks of Tiron came to the Borders and wrote down what they found.

My quarry was a collection of 562 documents or charters bound together in what is known as the Kelso Liber. Published by a nineteenth-century gentlemen’s antiquarian association, the Bannatyne Club, the Liber is a singular thing. As a printing job it is remarkable as it sets out precisely the homespun, everyday Latin turned out by the monks of Kelso Abbey’s scriptorium. They wrote on precious vellum and parchment and to save space they developed an inconsistent shorthand which, maddeningly, the printers and proofreaders had reproduced in all its inconsistency. However, once I had cracked its codes I found behind the idiosyncratic Latin a terse and sometimes elegant style and, with documents dating from 1113 to 1567, a surprising continuity of expression.

The twelfth-century documents of the Kelso Liber describe important places, a busy economy, and great wealth gifted to the Church. King David I moved the Tironensian monks from his Forest of Selkirk to Kelso so that he could concentrate economic, military, administrative and spiritual power in one place. He already held a massive royal castle across the Tweed from Kelso at Roxburgh, while beside it was his royal burgh of the same name. Established as an international centre for the trade in raw wool, Roxburgh was booming in the early twelfth century. It contained four churches, a grammar school, five mintmasters and by 1150 a new town forced the expansion of the town walls to incorporate it. David I needed literate men to help him administer his kingdom; he was very often at Roxburgh and so he moved his new abbey to Kelso for convenience and strength. And for a spiritual focus to confer prestige and dignity on all around it.

The foundation charters of Kelso Abbey list a long, immensely detailed and rich inventory of property, services and hard cash given by the king and by wealthy subjects anxious to impress him. Impossible to measure in today’s values, perhaps the fabulous new wealth of the monks is best expressed by a telling comparison. By the end of the sixteenth century most, but not all, of what remained of the abbey’s patrimony was appropriated by the Kers, a notorious Border clan based at a nearby stronghold, Cessford Castle. The Kers took a new title from the old castle and burgh, then became the Innes-Kers (Ker is pronounced ‘Car’) and are now the Dukes of Roxburghe (with an ‘e’), one of the wealthiest and most widely landed families in Britain.

Twenty miles downriver was another bustling town much written about in the Kelso Liber. The port of Berwick-upon-Tweed was the main exit point and trading post for the raw wool shipped out to the primitive cloth factories of Flanders and the Rhine estuary. Colonies of Flemings and Germans were settled in the town in the early twelfth century and once again generous portions of the customs revenue, valuable property in the town, salmon fisheries in the Tweed estuary and many other rights and services were gifted by the king. These properties, incidentally, only escaped the clutches of the acquisitive Kers by dint of Richard III incorporating Berwick as part of England in 1483.

Being the supply end of an embryonic textile industry in Europe, Roxburgh and Berwick formed together the beating economic heart of medieval Scotland. When they addressed charters to their Scottish, French, Flemish and English friends, David I and his successors reflected a busy, expanding cosmopolitan society. And so long as the English and the Scots remained friends, Roxburgh, Kelso and Berwick boomed. But with the accidental death of Alexander III in 1286 and the drying up of legitimate heirs to the Scottish throne, the expansionist Edward I of England turned his attention northwards, and then followed it with his armies when he did not get his way. Centuries of intermittent border warfare ensued. Trade declined, international contact virtually ceased, and over time the Borders became a place where people crossed a frontier on their way north to do business in Edinburgh, or south to London. Berwick was split from Roxburgh, and ultimately the latter diminished to extinction.

It is easy to forget the bustle of the market place, the buzz of language – English, Scots, Gaelic, Flemish, French and German were all spoken as deals were struck in the Market Place of Roxburgh. It is all gone now, without leaving any mark on the landscape. Only the sheep are still there, quietly grazing where once their fleeces brought promissory notes of exchange from Flemish merchants.

What became increasingly clear to me as I read the Kelso Liber, all of it, was how important this place was. By any modern measure Roxburgh/Kelso was the capital place of Scotland in the twelfth century. It generated immense wealth, it minted the coinage of the young kingdom and the king set his seal on many hundreds of documents in Roxburgh Castle.

However, an important question hovered over all this. Why is this large city not noted in any source before 1113? How can it be that such an important place makes such a dramatic, instant historical appearance, like a medieval Atlantis emerging from the mists of anonymity? The truth is that Roxburgh was not built the summer before the monks arrived and sharpened their quills to write about it. Clearly the town had been established for a very long time before that. But the fact is that there are no documentary facts. Nothing to refer to except common sense and a knowledge of the place and its name.

While the consistency of expression, of grammatical form and of vocabulary over the 562 charters written between 1113 and 1567 in the Kelso Liber is remarkable, there is a quiet, barely discernible undercurrent of change which flows through that record of 450 years of experience in one place. When the Tironensians arrived in the Borders from France, they would have understood little of what local people had to say to them. As members of the French-speaking ruling élite imported into Scotland by David I, that may not have mattered much. Except in one vital area: land. Most of the abbey’s new wealth was reckoned in acreage and in order to record their gifts clearly and safely, the clerks of the scriptorium needed to know two things: the name of the place they were to own and its precise boundaries. A difficult business and the monks no doubt lost a good deal in the translation. There are nearly 2,000 place-names scattered through the documents and, even allowing for radical spelling variants, 112 do not appear on any map or in the recollection of anyone who knows the ground around Kelso. It is true that not all of the 2,000 names are located near the abbey. The monks held land as distant as Northampton, but even so 112 disappearances is surprising. The lost names are often exotic: Karnegogyl, Pranwrsete or Traverflat; but I began to see that they all shared one obscure linguistic characteristic, something that turned out to be very important to this story. Buried in the Kelso Liber is an example that explains what happened.

The Scottish Borders

To the south-east of Edinburgh, on the other side of Arthur’s Seat from Holyrood Palace, is the well-set suburb of Duddingston. The monks of Kelso owned part of the medieval village which they spelled as ‘Dodyngston’ in a charter which notes that it belonged to a man with an English-sounding name, Dodin. As place-names go, a simple enough derivation. But then the clerk added, for clarity, that Dodyngston used to be known as Trauerlen. This turned out to be a Welsh name which breaks into three elements: tref is a settlement or a stead, yr means ‘of’, Llin is a lake. The settlement by the lake, a place good for skating in winter. (One of Sir Henry Raeburn’s most famous portraits is of the Reverend Robert Walker skating on Duddingston Loch.) The first elements in the three examples of extinct toponymic exotica quoted above are also Welsh: Caer for fort, Pran for tree, and again Tref for settlement.

It became clear to me that the 112 lost names did not all disappear. Many of them were discarded as new people arrived in Scotland anxious to stamp their identities on those properties. The Old Welsh names were swept aside as English speakers made these places their own. Nowhere was that more true than in Calchvyndd which the monks quickly boiled down to Kelso.

But what this process of renaming also told me was that the Old Welsh language culture was near the surface. Trauerlen was rejected by Dodin and the clerks of the abbey scriptorium but I am certain that it stayed for generations in the mouths of the ordinary people who formed the cultural bedrock of southern Scotland. People who understood Welsh names and, as I will show, who may have even retained remnants of the old language far into the medieval period.

There are some fossil remains of Welsh names that can easily be seen nowadays. The new people, like Dodin, took the best land but up-country in the more remote areas away from the population centres the old names persisted. Another tref makes the point. A sharp-eyed traveller on the A68 going south might notice a road sign near Lauder pointing to a by-road to Trabrown. In the collection of documents for Dryburgh Abbey4 it has the give-away spelling of Treuerbrun or Tref yr bryn, or ‘the settlement on the hill’ or, since it is now a farm place, better as ‘hillstead’. The name survived because the land was less sought after and the people in whose mouths Trabrown felt more comfortable retained the power to call it what they had always called it. These stubborn men and women form the basis of this story and the place-names they left to us will continually light our way through the voids of Dark Ages Scotland.

At the points in our history where documentary evidence is almost totally lacking, historians have for the most pan regarded toponymy – the study of the place-names of a country or district – as a footnote rather than a guide. They have mistrusted the land as a text in itself and ignored our eternal, primal connection with the ground we live on. We are bound to leave our mark in more ways than an archaeologist can dig out and the names of our places beat out the rhythm of history more steadily and honestly than a stray text from a propagandist monk anxious to apply his partial slant to a piece of history somebody else told him. Too much importance has been attached to documentary history, too little to what the landscape can tell us.

Here is a good example of how dry etymology can lead to daft conclusions even in a case where some play is allowed to toponymy. Melrose has been a holy place for at least a millennium and a half. Saints Cuthbert and Aidan and possibly Ninian had strong connections, as did the mother house at Lindisfarne. The original Celtic monastery lay in a loop of the River Tweed two miles to the east of the later Cistercian abbey so beloved of Sir Walter Scott. The name Melrose is everywhere written up as a reflection of the topography. From Gaelic the second element is ros for ‘a promontory’ – the loop of the Tweed – while the first is maol which means ‘bare’. So Melrose is Mailros or, it is widely repeated, ‘bare promontory’. That is a derivation produced by someone who has never visited the site and has missed an obvious connection with the known history of the place. Certainly Old Melrose lies on sufficient of an inland promontory to allow the second element, but ‘bare’? The fields at Old Melrose, watered by the nourishing currents of the Tweed, are lush with corn each summer and in fallow years the farmer cuts some of the best hay in the Borders. It may be a promontory but it is not bare. What ‘maol’ actually refers to is the men who lived at Old Melrose. In both Gaelic and Welsh it means not only ‘bare’ but also ‘bald’. Celtic monks had a severe tonsure cut from ear to ear right over the crown of their heads. Melrose got its name because local people called it ‘the promontory of the monks’.

The point of this example is a simple one. If scores of historians can fail to see the value of correct toponymy with a name and place as famous and important as Melrose, what else has been missed?

These are all questions that jumped out at me as I worked on my original book on Kelso. They told me that through the history of my native place another river ran and although I had little idea at the time where it would lead, it bothered me that so much that was obvious to me, a local amateur, was so ignored or, it seemed, wilfully misunderstood by the professionals.

Before I finished my history of Kelso, three more ill-fitting pieces of information disconcerted me enough to keep on interrogating the conventional wisdom.

In my researches I came across a spectacular liar. At first I thought I had made a sensational discovery. In the British Museum reading room catalogue I found an entry from a man who wrote under the name of Thomas Dempster. In 1627 he published a history of Scottish churchmen with the sonorous title of De Viris Illustribus Ecclesiae Scotticanie. The book records a dazzling succession of intellectual achievements and international contacts made by the abbots and priors of the monastery of Kelso. According to Dempster the twelfth-century Abbot Arnold wrote a treatise ‘On the Right Government of a Kingdom’. His successors produced volumes on the freedom of the Scottish Church, appeals to the court of Rome, and in the late fifteenth century the Prior Henry was described by Dempster as an intimate friend of the Italian poet Angelo Poliziano and the philosopher Marsilio Ficino, both of whom were part of the Medici court circle during the zenith of the Florentine Renaissance. Clearly Prior Henry was a man of some erudition since Dempster tells us that he translated the work of Palladius Rutulius into Scots verse and carried on a lengthy and learned correspondence with the smart set in Florence.

All this would have been remarkable, if any of it had been true. I spent fruitless days searching through library catalogues, bibliographies and incunabula for any corroborative reference to these works. Not only did I fail to find the learned works themselves, I came across no trace of them either, no mention of their existence by any other writer. The extraordinary thing is that Dempster invented it all. He was an undergraduate at the University of Padua which, having a long tradition of foreign students, organized each group into different ‘nations’. As a member of the Scots nation Dempster may have harboured a sense of cultural inadequacy in the company of relative sophisticates from France, Germany and Italy. Compared with the glittering intellectual achievements of the Italian Renaissance, an upbringing in backward, backwoods Scotland must have seemed dreich and unimpressive, leaving Dempster as only a listener in company, with nothing to talk about, no status. So he invented it. By writing his De Viris Illustribus Ecclesiae Scotticanie he hoped to borrow sufficient spurious lustre to allow him to pose as a substantial man, to be a talker, an understander, a member of the European intellectual mainstream. Poor man, so ashamed of his origins, he was forced into fiction to cover them up.

Since he wrote so much about Kelso Abbey – it is in fact the focus of his book, and has a correct sequence of abbots and priors in his list of illustrious Scottish churchmen – I think it is likely that Thomas Dempster came from Kelso or from the Borders. That belief is bolstered by the early part of De Viris. No doubt in pursuit of more reflected glory, he makes an interesting claim. Some of southern Scotland’s earliest kings were descended from Romans who had ‘worn the purple’. He goes on to say that they were, of course, cultured men even though they spoke a British language and their Latin was poor.

Either this is a fleeting glimpse of some research by Dempster into the work of very early historians (unlikely given the fiction he went on to produce) or it is a repetition of local traditions which were still in currency in the 1620s but are lost to us now. Despite my angry disappointment at how much time I had wasted on the inventions of Thomas Dempster, his references to British kings in southern Scotland whose forebears had worn the purple stayed with me, and intrigued me. They had the ring of remembered truth about them.

Traditions that carry the crust of old wives’ tales around them are rarely worth more than passing interrogation. Black cats crossing our path as a good portent appeals only to the irrational in us all, but traditions which are held in common, which are repeated with some precision, which carry the weight of years upon them – these are worth parsing for historical meaning.

In the Scottish Borders each summer sees several unique festivals. Associated with the towns of Selkirk, Hawick, Langholm and Lauder there occur what are known as the Common Ridings. Although surrounded by fun and endless opportunities for socializing, the core of these festivals is profoundly historic. For at least half a millennium and probably much longer the young men of the towns have ridden out in midsummer to check the boundaries of the common land. It is the origin of the phrase ‘beating the bounds’. Particular trees were often used as triangulation points between other natural features such as streams and hilltops and to mark them out from others the riders beat the bark with swords and sticks so that they would recognize the same tree next summer. And as a matter of further incidental etymological interest the procession of riders is led by two Burgh Law men, or the Burley Men, who were no doubt often heavy-set individuals.

The Hawick Common Riding is one of the oldest and I often went to cheer on the riders with my mother. She was a native of Hawick or a ‘Teri’ as they nickname themselves. A strange word, it comes from a motto anciently associated with the Common Riding. On the plinth of a statue of a Hawick horseman, the complete phrase is inscribed: ‘Teribus Ye Teriodin’. No one was ever able to tell me what it means. But when I realized how important the Welsh language underlay was to the history of the Borders, the meaning came easily. It is a Welsh phrase, Tir y Bas y Tir y Odin, not much changed by centuries of use. It means ‘The Land of Death, the Land of Odin’. What that has to do with the Common Riding will be explained later, but the significance for me was pivotal. How had a Welsh phrase, not understood, become the unquestioned emblem of a place I thought I knew well?

Land, and its boundaries, is in essence what this story is about. As much as what the clerks of Kelso Abbey’s scriptorium wrote down about the ground they found themselves in possession of, what people remember now in these traditions is important. And it was important 800 years ago. Here is an example of what I mean.

In 1202 King William the Lion of Scotland was asked by Pope Celestinus III to arbitrate in a long-standing dispute between the monasteries of Melrose and Kelso over boundaries.5 This had arisen as a result of the transfer of the abbey from Selkirk to Kelso in 1128. Seventy years later it still rumbled on. King William’s reaction was to delegate.

I brought together the ancient and honest men of the countryside into my presence and then I put the enquiry into their hands.

At length they came to my court at Selkirk … I am bound legally to the evidence of the honest and ancient men of the countryside. I wish the monks of Kelso to give up for ever to the monks of Melrose two bovates of land, two acres and pasture for 400 sheep which the monks of Kelso used to hold. On that day discussion of the matter ended.

This dispute had ground on for seventy years because there was a great deal of very valuable land at stake, in today’s reckoning perhaps two million pounds. And the striking thing is that William the Lion immediately fell back on tradition, on what ordinary people who lived in that place could remember. Something modern historians are loath to do. Indeed I doubt if a modern court of law would accept a tradition as absolutely determinant in a dispute of this scale, particularly if one side was able to produce a piece of paper to back its claims. I fear we dismiss tradition too readily in piecing together pictures of the past. I would be inclined to set greater store by the honest and ancient men of the countryside over against Thomas Dempster and his literary fancies any day. This is a point worth bearing in mind as my narrative progresses.

But first, one more piece of the unmade jigsaw which lay around the edges of my research into the history of Kelso. As I became more and more aware of how deeply the Welsh language underpinned my work, I came across a piece of great British history: The Age of Arthur by John Morris.6 A history of Britain from 350 to 650, it felt like a huge summary of a life’s work; the sweep of the thing is majestic and the depth of learning is humbling. And yet it contains a remarkable error of geography. Not only does Morris believe profoundly in a historical Arthur, he also attributes to him a long period of British supremacy over the Angles and Saxons in the sixth century. Having successfully resisted the Germanic invaders, Morris believed that a strong British state and army existed over a wide swathe of the south Midlands including Dunstable and Northampton and stretching westwards to north of Gloucester. It had a king, wrote Morris, called Catrawt and it was known as Calchvyndd.

That set me thinking hard. Morris’s footnotes and appendices are exhaustive and it was easy to see how he had got the location of Calchvyndd 300 miles wrong. Later Welsh poets and transcribers had appropriated the stories of ‘The Gododdin’ and applied them to the south-west, merging them with stories told in Welsh about Wales.

As I read more of the history of the Dark Ages, I could see that much of it had become even more skewed compass-fashion than John Morris’s work. The Welsh-speaking peoples of southern Scotland had been almost completely forgotten, their history even removed and stuck on to that of other places. However, like many Scotsmen, I preferred to nurse this thought as a grievance rather than treat it as a spur to action.

Three months after the party for the publication of my history of Kelso and our family dinner, my dad died suddenly of a heart attack. I remember it was a foul February night when the young doctor phoned me. There were snow showers at first and then a blizzard blowing down on the north wind as I drove carefully south to be with my mother. There was a lot of late snow that winter and preferring to drive in the light I went to Kelso most Sunday mornings. I recall one journey in particular, like an experience sealed within itself. I travelled slowly down the Leader valley into the Tweed basin and the heart of the Borders. A yellow slanting winter sun threw the shapes of the snow-covered ground into detailed relief. It was as though the landscape had been wrapped in clinging white tissue. I drove past the great prehistoric fort of Eildon Hill North. I could see the defensive ditches clearly circling the round summit, enclosing scores of ancient hut platforms. These were things I had never really looked at before, even though I had passed the hill a thousand times. I stopped the car at the turn-off down to Old Melrose and scrambled up the railway embankment on the opposite side of the road. At the foot of Eildon Hill North lay the Roman fort and town of Trimontium (there are three Eildon Hills) and although not one stone has been left standing upon another, I could clearly see the line of one of the walls in the snow-covered fields near the village of Newstead.

Even though nearly two millennia had passed since Agricola’s legions had dug in at Trimontium there had to be a way to tell the story of what happened in the Borders before the Romans arrived, after they left and before the arrival of more outsiders with David I’s French monks in 1113. We seemed to depend absolutely on other people to write our history for us. And more, there had to be a way of righting the imbalance in Dark Ages historiography, correcting the bias to the south.

Standing in the snow in the Borders in the February of 1987, it occurred to me that I should stop complaining and start working.

3

THE NAMES OF MEMORY

Let me begin with the Old Peoples. I do not know what else to call the communities who lived in the Borders before the Romans came. Until Pliny the Elder and Tacitus gave them names, locations, and some character, the Old Peoples left only shadowy marks on the landscape: great earthworks on the hilltops, burial sites, flint tools, cultivation terraces. And although the pains taken by archaeologists tell much that is useful about what they ate, how they sheltered themselves and where they built their huts, they tell us nothing of what they thought, how they felt, what they feared and what language they spoke. Because the Old Peoples left no written record they seemed to me to be dumb, grey figures in a distant landscape. I had read every history book I could find, gone to the National Library in Edinburgh to look at articles in periodicals even more detailed and learned. But still I could get no sense of who these people were.

At least that is how things seemed to me at first. But after a time I realized that I had been looking in the wrong place. What remains of the story of the Old Peoples is not to be found on the shelves of the National Library of Scotland. It lies all around us. If I wanted to hear the echo of how they spoke, some words of their language, then I realized that I should listen to the landscape. Names. Names of places, of natural features and most importantly the names of rivers. The Old Peoples gave the landscape names and many of them have survived. And since names are words, we can hear them talk by listening to the landscape.

Now, this will take a lot of explaining and a good deal of what I have found is highly conjectural. Names for peoples and places can be conferred in the most unlikely and confusing fashion. Here is a modern example of how this historical approach can go badly wrong.

Why do the Mexicans call the Americans Gringos? It is a strange term with an even stranger origin. When Davy Crockett, Jim Bowie and the other heroes of Texas’s war against Mexico were besieged in the Alamo, they had a small force of about eighty Scots mercenaries with them. The Scots’ marching song was the folk-tune ‘Green Grow the Rashes O’ and that is why Santa Ana’s army and finally the whole of Mexico called the Americans Gringos.

Historians with an interest in etymology might believe that a recital of a nation’s nicknames, or terms of abuse even, would provide a useful gloss to a study of that nation. However the Alamo story illustrates what a risky set of assumptions rumble around inside that way of thinking. The Mexicans believed that they were describing Americans when they were actually describing a band of Scotsmen, and they used an accidental term which says nothing much about any of the groups involved, except perhaps that early nineteenth-century Mexican soldiers had a poor grasp of English and knew nothing at all about traditional Scottish folk-songs.

So history from names is a risky business. Be that as it may, I am forced by the lack of anything else to go on to embark on this course. However, I hope that the process will not seem too laboured and the results not too scanty.

The oldest names in the landscape are river names. The rivers Thames, Tees, Tyne, Tweed and Tay have been so called for millennia. All begin with ‘T’ and all lie on the eastern coast of the country. That is because they were named by people who walked across the North Sea to Britain. The last Ice Age cleared the Tweed valley by about 7000 BC but it still left Britain connected to the continental land mass by low-lying, swampy plains which are now the North Sea. Archaeology on the banks of the ‘T’ rivers shows that those migrating were fisher people who used figure-of-eight flint and chart sinker-stones for their nets. They came to Britain in small, unrelated bands but they shared a language. They sought out navigable rivers and in boats they travelled up them into the interior of the densely forested unpopulated countryside. Archaeological finds of pottery and their places of burial trace the progress of the Old Peoples upriver and up-country. Densest along the banks of major rivers and particularly at the confluence of large tributaries, the finds gradually thin out inland and finally disappear at the foot of the watershed hills. Each time a band of these people came to a large river they called it the same thing: tavas is a Sanskrit root which means ‘to surge’. All the names of the ‘T’ rivers come from the same word. In AD 80 the Roman historian Tacitus calls the Tay ‘Tanaus’ or ‘Taus’, a much clearer echo of the Sanskrit.

That means that after the last Ice Age Britain was first populated by a people who spoke an Indo-European language but were not yet Celts. The persistence of the names might be explained by the fact that the Celtic-language-speaking peoples who followed them understood what tavas meant, they understood the Old Peoples who pointed at the Tyne or the Thames and said what it was: the surger or surging river. A verb that became a name.

The Celts had another reason not to change the names of the rivers they found. They did not dare to. In Celtic story-telling rivers are magical phenomena possessed of cataclysmic power and often contain supernatural creatures easily given to anger and evil-doing. Gaelic legends still remember the Kelpies, water horses who drag the unwary to the depths. St Columba was the first to report the Loch Ness monster, while in Breadalbane there was, according to legend, an Uruisk tribe, half human, who haunted streams and waited at fords for careless travellers. So strong was this tradition that the Celts gave the chief of this tribe a name, Peallaidh, which they then preserved in Obar Pheallaidh, or Aberfeldy as it is now rendered down into English.

Rivers were thought to be sentient in those days long ago but even now, in what we are pleased to think of as more rational times, they still retain a power that can reach down the centuries and chill our bones. Here is an old Border rhyme which imagines the Tweed’s tributary, the River Till, talking.

Till said to Tweed

Though ye rin wi’ speed

And I rin slaw

For ae man ye kill

I kill twa.

In the Border country, to draw a tighter focus, there is a network of names for various sorts of rivers which supply more words and more information. Tweed and Teviot are ‘T’ rivers, the arterial waterways of the area. They surge, are big rivers, navigable in small boats for much of their length. Then there is a second group of names: the Jed Water, the Kale Water, the Ettrick and the Gala Water. Just as modern English imposes a secondary classification of ‘water’ as opposed to river, so the Old Peoples gave them a lesser name. They are the babbling, talking rivers, large enough to be noisy but not navigable. Kale and Gala come from a similar Indo- European root, kel, meaning ‘to shout’ or ‘to cry’, while Jed and Ettrick are from iekti or jekti for ‘to talk’ or ‘to babble’. Two of these ancient names have been joined to much younger words to form the town names of Jedburgh and Galashiels.

Then there is another lesser group of streams which have held on to Sanskrit names. There are two Allan Waters and two Ale Waters in Roxburghshire and Berwickshire. Their duplication in such a small area is interesting but the derivation is harder because it is hidden inside another name. On the Ale Water is the village of Ancrum. In early monastic documents it is written in the more pulled-out version of Alnecrumba, or Alncromb or Alnecrum or Allyncrom. These show the old name of the Ale Water, which comes from the Sanskrit root alauna which means ‘to flow’ or ‘to stream’. The clearest memory of this name appears outside the Borders in Roman military maps of the north of Britain. Three places bear the name Alauna and two of them lie on rivers where the modern name shows traces of the name given by the Old Peoples. The first and best known Alauna is Alnwick in Northumberland: the old town stands on the River Aln and although it has attached an Old Norse suffix, the example is there. Less clear is the Alauna in Cumbria. The unconnected name Maryport stands on a coastal site but the derivation falls into place with another river name, this time the Ellen which washes into the Irish Sea just below the town. The final example is near Ardoch in Perthshire but the reason that prompted the Roman reconnaissance units to name the place Alauna has been lost, probably covered over by later Gaelic place names.

In Berwickshire and north Northumberland there are more water-names such as the Blackadder and Whiteadder rivers that also come from Sanskrit roots.

All this shows that the Old Peoples spoke an Indo-European language like Sanskrit, which is close to the sort of Hindi now understood by ordinary people in India, and that they travelled and lived by water which they named with some sophistication. Although it is difficult to judge how numerous they were, they were certainly not anonymous. Five thousand years after they fought the currents up the Tweed, we in the Borders unconsciously use their words every day.

Also unconsciously, and particularly around Kelso, we complete in our everyday speech an extraordinary historical circle with the Old Peoples. Bina Moffat, my grandmother, used to buy kitchen utensils, and have knives sharpened by ‘Muggers’. This is not as dangerous a practice as it might appear. By Muggers she meant Gypsies, and they often drove their carts into Kelso to offer their wares and services. Muggers is a corruption of Magyars or Hungarians and it is a more sophisticated linguistic description than Gypsies. For they had little to do with Egypt or, come to that, with Bohemia. Their language does not fit neatly into the Indo-European group. Like Hungarian, Finnish, Basque, or Estonian, Romany is in its essence much less like the Mediterranean romance languages or the northern European Germanic. In fact it is a greatly corrupted dialect of Hindi with an eccentric admixture of words from several European languages. At some unrecorded time someone had understood this linguistic particularity and that is why my grandmother called the Gypsies ‘Muggers’, not because she believed they might steal her purse. That later American gloss no doubt derives in part from attitudes to these nomadic groups but in the 1950s in Scotland a Mugger was more likely to sharpen your knife than threaten you with one.

The reasons why Gypsies were not foreign to me as a child were part historical, part linguistic. Since the late Middle Ages certain tribes had from the king a grant of rights to overwinter at the village of Yetholm which stands eight miles from Kelso in the foothills of the Cheviots. They spoke Romany and referred to themselves as the ‘Roma’ or, if it was one person, a ‘Rom’. Although they used it as a secret language or a cover tongue the Roma had become so familiar to generations of Kelso people that many of their words leaked into local dialect: basic terms such as gadji for man, manishi for woman, pani for water and jougal for dog. Two words that have transmitted themselves into modern drug culture via the film Trainspotting come from Romany: bari means good and raj means crazy. But perhaps the most telling piece of vocabulary for this story is a Romany word for river. They call it tavvy.

My grandmother had another name for the Muggers. After they struck their camp at Yetholm in the spring and they went on the road with their horses, carts and caravans, she called them the ‘Summer Walkers’. Looking back now their lives and their language seem to me to whisper the story of the Old Peoples. Far from being strangers, perhaps they have wandered home.

4

THE HORSEMEN

Around 700 BC, several thousand years after the Old Peoples came, groups of horse-riding warriors were seen in the Tweed valley. They came from continental Europe and they spoke a language that I shall call P-Celtic. Tall, fair-headed and vigorous, they brought a military technology based on the horse and chariot which must have given them an immediate and terrifying dominance over the river-folk they found in southern Scotland.

It is impossible to know exactly when and in what numbers the P-Celts came but it is clear that their culture quickly overlaid the Old Peoples’. Their names are everywhere in the Tweed and Teviot valleys, describing all kinds of geographical features, as well as settlements, fortresses and, in time, the arrival of the Roman legions in AD 80. So widespread and so versatile, the names the P-Celts gave to the landscape suggest that they were indeed numerous and that they came to the Borders in successive waves.