Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Birlinn

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

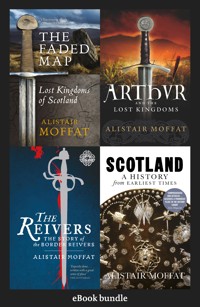

Uncover the story of Scotland with Alistair Moffat's history collection. From the Ice Age to the modern day, this bundle leaves no stone unturned. Journey through the long-lost kingdoms of Roman times and the Dark Ages, uncover the bloodshed wrought by the Border Reivers for two centuries, track down the true King Arthur, and learn the true story of how Scotland became the nation it is today. 'Moffat plunders the facts and fables to create a richly-detailed and comprehensive analysis of a nation's past' – Scots Magazine Titles included in this bundle are: The Faded Map Arthur and the Lost Kingdoms The Reivers Scotland: A History From Earliest Times

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 2806

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

THE ALISTAIR MOFFAT HISTORY COLLECTION

Alistair Moffat

eBook Bundle

The Faded MapArthur and the Lost KingdomsThe ReiversScotland: A History From Earliest Times

This eBook was first published in Great Britain in 2023by Polygon, an imprint of Birlinn Ltd

Birlinn LtdWest Newington House10 Newington RoadEdinburghEH9 1QS

www.polygonbooks.co.uk

Copyright © Alistair Moffat, 2010, 2012, 2016, 2017

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored, or transmitted in any form, or by any means electronic, mechanical or photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the express written permission of the publisher.

eBook ISBN 978 1 78885 631 7

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication DataA catalogue record for this book is available on request from the British Library.

The Faded Map

The Faded Map

LOST KINGDOMS OF SCOTLAND

Alistair Moffat

For Hugh Andrew

Contents

List of Illustrations

Introduction

1 Shadows

2 The Faded Map

3 As If Into a Different Island

4 Kingdoms Come

5 After Rome

6 The Baptised

7 Bernicia

8 Strathclyde

Bibliography

Index

Also Available

List of Illustrations

The Catrail, near Galashiels

Callanish, Lewis

The Lochmaben Stane

The upper Solway Firth at low tide

The site of Flanders Moss

Traprain Law, East Lothian

Addinston Fort, the site of the Battle of Degsastan

Burnswark Hill

Dumbarton Rock

The Antonine Wall at Rough Castle

Hadrian’s Wall, showing the Whin Sill

Bennachie, the site of Mons Graupius

The Farne Islands, looking towards Bamburgh Castle

Bamburgh Castle

Lindisfarne Castle

Roxburgh Castle

From Roxburgh Castle, looking east

The site of the monastery of Old Melrose

The Eildon Hills

Bewcastle Church, Cumbria

Bewcastle Cross

Manor Valley

St Gordian’s Cross, Manor Valley

Stirling Castle

Edinburgh Castle

Introduction

VERY LITTLE CERTAINTY, only occasional phases of continuity and hardly any clarity at all are the sorry string of characteristics to be found everywhere in this book. Scotland or, more precisely, north Britain in the Dark Ages seems a tangle of confusion, a story told in sometimes contradictory fragments and a few rare flickers of light. From late in the last millennium BC to AD 1000 and even beyond, it is a tale of shadows and half-lit edges.

Only the land, its rivers and lochs and the seas around it remain and, although the appearance of Scotland has changed over the course of a thousand winters and a thousand summers since, its fundamental shape and scale have endured. The sands and the tides, the hills and high valleys, the great rivers, the long-lost wildwood, the impenetrable marshlands and the ancient names of places have a rich story to tell. The land has its own certainty, continuity and clarity and, where it can, this book attempts to thread these into the weave of our early history.

Such as it is, much of what we might recognise as a history of Scotland in the first millennium AD has been supplied by outsiders. Greek travellers, Roman military historians and map makers, Irish annalists, Welsh bards and chroniclers now thought of as English have left us most of what passes for a narrative in what follows. Much has been lost and often it is the random discovery of an object, the recognition of a piece of dusty sculpture as great art or the realisation that some of the men of the north of Britain were very influential in their time that reminds us that a lack of a coherent history written by those who lived it is only an accident. Because records did not survive, we should not drift into the unthinking assumption that the society of Dark Ages Scotland was incapable of compiling them and was therefore somehow primitive and less sophisticated than others.

As a further discouragement, it should be made clear at the outset that the principal focus of this book is failure. The losers have, of course, been eclipsed by the winners in the history of Scotland. Excellent treatments of the rise of Dalriada, the Gaelic-speaking kings of the west and their eventual takeover of the whole country exist. And the story of the Pictish kingdoms, one of the great mysteries of our history, has been investigated and exhausted by talented historians. The Scots and the Picts appear in this narrative only when they shed light on the peoples they defeated or subjugated.

Instead a dim light is shed on the forgotten dynasties that died away and failed. Their lost kingdoms are the proper subject of this book. Where were Calchvynydd, Desnes Mor and Desnes Ioan, Manau and the land of the Kindred Hounds? Who were the Sons of Prophecy, the Well-Born, Macsen, Amdarch, the kings of Ebrauc and the treacherous Morcant Bwlc? What happened at Arderydd, Degsastan and Alt Clut? Where were the Grimsdyke, the land of the Haliwerfolc, the sanctuary of St Gordian, the Waste Land and the Raven Fell?

Most of these lost or half-remembered names are to be found in the landscape, overgrown by ignorance, pushed to the margins of our history by events elsewhere. The limitations of this book are all too obvious but its geographical limits require a little explanation. It is principally the ‘faded map’ of southern Scotland, the lands south of the Highland Line. Those lost kingdoms that spoke dialects of Old Welsh are much discussed and the final flourishes of the remarkably resilient Strathclyde Welsh close the narrative. The other significant language of Lowland Scotland was of course English and a concerted and extended effort is made to assert the Bernicians as one of Scotland’s peoples. The arrival of their language and the glittering achievements of the dynasty of Aethelfrith are seen as a central part of Scotland’s history. Bernicia is a kingdom lost to us in the pages of histories of England.

Finally, a note on the boxed notes in the text: these deal with snippets of detail and related information and are of incidental importance in a story which needs every bit of information it can find.

It is to be hoped that in these pages the ‘faded map’ of Scotland will acquire some colour once more. The story of our lost kingdoms is not merely a matter of footnotes for the curious. Failure has its own fascination. Losers in our history deserve our attention and perhaps our respect. Scotland was never inevitable.

1

Shadows

IN FEBRUARY AND MARCH, the hungry months of the late winter, even the best fields are grazed hard, their grass pale and nibbled to its roots. Good farmers use every inch of pasture to nourish their pregnant ewes and, in the pillowy hills by the River Tweed, it is surprising to see a copse occupy a long stretch of good ground for no apparent reason. But it turns out that there is one. Deep in the tangle of briars and hawthorns and surrounded by a rusty barbed wire fence lies the shadow of an ancient kingdom. Perched on a south-facing hillside between Galashiels and Selkirk in the Scottish Border country, the long and prickly copse hides a stone-filled ditch with a steep bank on its northern edge. The farmer has fenced it to keep curious lambs from injury and mischief and left the scrub and tumbled tree trunks as a welcome shelter from the winter winds. Curious human beings who avoid becoming hanked on the barbed wire and push their way through the briar thorns will find themselves standing inside another time and another place. In the still of a summer evening, the dense canopy shades the lichen-covered stones of the ditch and in the quiet glade there is a silence and the sense of a long past.

Nothing appears to be artificial – there are no obvious marks of the work of men and women and no signs of occupation. The deep ditch has been filled with stones picked up in the surrounding fields by generations of ploughmen and shepherds. None seems to have been carved or worked in any way. And yet this place was made by the back-breaking labour of many people, hacking soil and rock out of the earth with mattocks and picks, filling baskets, lifting them, carrying their loads to the bank above and piling the upcast ever higher. The ditch was deep – almost two metres in places – and, with the bank above it, the whole earthwork measured six metres across. This place was important. At least fourteen centuries ago, the ditch and its bank marked a frontier, the limits of two of the lost kingdoms of Scotland.

Known as the Catrail, the beginnings of the boundary have been traced a few miles to the north, near the banks of the Gala Water by Torwoodlee. As it climbs up the steep slopes above the flood plain, the ditch circles a broch, a stone tower probably built in the last centuries of the first millennium BC, perhaps occupying the site of an earlier hill fort. Formed with immensely thick drystane walls and circular in plan, the broch dominated the landscape, visible up and down the river valley, standing on a high and prominent spur. The frontier ditch skirted the great tower and it may be that, at some point in an overlapping history, the strength of one was associated with the integrity of the other.

After the line of the Catrail passes to the west of the modern town of Galashiels, it can be difficult to trace, often showing only as a shadow cast by early or late sun. When snow melts, the last of it sometimes lies where the old ditch has almost been ploughed out or filled in by farmers so that a slight depression is all that remains. As the Catrail reaches the tangled briar copse on the hillside between Galashiels and Selkirk, another tremendous fortification once reared up behind its line. On the summit of the ridge stands a plantation of spiky Norway spruces surrounded by a circular drystane dyke. Inside, screened by the evergreen trees, are the banks and ditches of an elaborate fort. Dug and palisaded some time in the first millennium BC, it is known as the Rink. An odd place-name, it is the stub of something longer and more revealing. Llangirick is, in part, an Old Welsh name coined by the communities who lived in the Borders before the arrival of English and the war bands who spoke its seventh- and eighth-century versions. Many Old Welsh place-names have survived. Peebles is from pybyll, which meant ‘a tent’ or ‘a shelter’ and probably referred to the shielings of shepherds or farmers. Kelso is from Calchvynydd, meaning ‘a Chalky Hill’. In Wales there are many llan names and it usually refers to ‘an enclosure’. There is a persistent local tradition that the second element of Llangirick is a memory of a Gaelic-speaking Scottish king. Giric reigned in the late ninth century and his war bands are said to have raided in the Tweed Valley. Perhaps they re-used the crumbling ramparts as a base for harrying the countryside around.

Below the Rink fortress, the frontier runs towards the banks of the Tweed and is picked up again immediately on the other side. What makes it almost certain that the Catrail was not a road but a boundary is the fact that it does not seek to ford rivers or pay much attention to natural features. In two places the ditch arrives at a sheer drop into a stream and carries on on the other side. Elsewhere its line goes from one side of a hill loch to the other and it often goes straight up ridges with no attempt to find an easier gradient.

Frontiers are the product of politics, of an agreement or bargain struck or at least a settlement of some kind, often a compromise. Another place-name suggests one. In the neck of land between the Tweed and the Ettrick before they meet below the Rink fort, lies Sunderland. An English name, it signifies territory separated or ‘sundered’ from a greater whole. The chronology may not fit (place-names are difficult to date) but in Sunderland there is a sense of an important boundary nearby, one which could not include it for some lost reason.

That reason may have been military. An alternative and equally plausible interpretation is that the construction of the Catrail was an act of war rather than an agreed peace. The ditch was almost always dug on the eastern or southern side of the earthwork and the bank raised to the north or west. That suggests that the Catrail was made to obstruct the advance of aggressors from the east, either mounted raiders or warriors on foot. And, if any did break through and had plundered cattle or other livestock, the ditch and bank would make it difficult for them to get away quickly with their stolen beasts.

The fact that several powerful fortresses lie close to the Catrail is also eloquent. They are always sited in the west or north and therefore behind the sheltering bank. And in turn that suggests strongly that this huge structure was thrown up by the peoples of the west and their kings.

Offa’s Dyke supplies useful analogies. Built by the great Mercian king in the eighth century, it was intended to inhibit raiding parties riding out of the Welsh hills. Although on a much larger scale than the Catrail, its principles are the same; there is a wide and deep ditch to the west and a high bank on the east made from the upcast. At 150 miles in length, from the Severn estuary to the Dee, it was a vast project, the largest archaeological monument in Britain and the most impressive man-made frontier in Europe. Land was the most precious asset our ancestors had and kings did not hesitate to expend enormous energies to protect it.

To the west of Selkirk, the Catrail is much harder to detect as it climbs into the hills above the Yarrow Valley. It may be that this long stretch was dug at a different period and guided by different authority. After crossing the river near the Yarrow Feus, the frontier swings south through the high wastes of the old Ettrick Forest before becoming much more defined as it reaches the Borthwick Water. Now engulfed by commercial forestry, the last few miles are, nevertheless, again emphatic, the ditch cut in long straight sections before terminating in the western ranges of the Cheviot Hills, near Peel Fell.

Earthworks are notoriously difficult to date. The most persuasive evidence for Offa having caused his dyke to be built during his reign, from 757 to 796, is to be found in Asser’s Life of King Alfred. Written 100 years after the event, the biography contains only one relevant sentence: ‘Offa caused a great dyke to be built from sea to sea between Mercia and Britain.’ The seas are assumed to be Severn Estuary and the Irish Sea while Mercia was Offa’s midland English kingdom and Britain was what is now Wales, seen by contemporaries as one of the last redoubts of the British. Written evidence like this is precious, much prized by historians of the so-called Dark Ages. And yet it is not entirely accurate. The northern section of Offa’s Dyke was never built and to maintain its line to the Dee Estuary and the Irish Sea, another huge earthwork, which lay a few miles to the east, was used. Known as Wat’s Dyke, it is forty miles long and was thought to be roughly contemporary with Offa’s Dyke. But archaeologists have recently found a fire site under Wat’s Dyke which was reliably carbon dated to around AD 446, much earlier than the reign of Offa.

No one has yet excavated the Catrail and parts of its fifty-eight-mile length may have been dug at different times or re-used older ditches and banks. Or the frontier may have been marked in different ways, and there were certainly substantial gaps where streams and sleep slopes seem to have sufficed. But the continuous 110 miles of Offa’s great dyke was certainly built in the second half of the eighth century, and it was thrown up quickly because of military pressure from the Welsh kings of the west. It seems highly likely that the Catrail had similar beginnings and for similar reasons.

Solid, physically imposing frontiers were very familiar to the communities of southern Scotland. They lived between two mighty Roman walls, the Antonine across the Forth–Clyde isthmus and Hadrian’s between the North Sea and the Irish Sea. But what was the military pressure in the western Tweed Basin that galvanised kings and lords to imitate the work of the legions?

In the seventh century, English-speaking war bands began raiding in the north. Riding out of the newly established kingdoms of Bernicia in Northumberland and Deira in Yorkshire, these warriors and their kings were ambitious, anxious to gain territory and prestige and successful in imposing overlordship in the Tweed Valley. In 603 a great general, Aethelfrith, led his war band to victory over the men of Aedan macGabrain, King of Dalriada. They fought at a place called Degsastan by the chroniclers, probably Addinston in Lauderdale. By 637 the English were laying siege to the seat of the Old Welsh kingdom of the Gododdin at Din Eidyn, now Edinburgh. Not recorded are the forays they made to the west, to the fertile farms and fields of the Upper Tweed. But make them they did for the seventh century saw native kings shrink back into their upland fastnesses and try to stem the tide of English takeover.

It is likely that these defeated, retreating rulers determined to draw a line through the Border hills, the frontier which has become known as the Catrail.

Further down the Tweed, English-speaking warlords were renaming the landscape. The old fortress at the junction of the Teviot and the Tweed, the strategic pivot known for centuries as Marchidun, became Hroc’s burh, the stronghold of the English warlord called the Rook. Roxburgh is the smoothed-out modern version. Much closer to the Catrail new settlements took a characteristic shape. At Midlem, originally Middleham, the village evolved as two rows of houses on either side of a central green and with long backlands behind. These were cultivated for many generations and show up well in aerial photographs. At Selkirk, on the flood plain of the Ettrick, a powerful magnate built a hall for himself and his warriors. It has left its name on the town. Selkirk is from Early English and it means the Hall Church. Only the faint traces of the wallstead, a large rectangle, can be seen from the air but the building was probably like its contemporaries. In the epic poem, Beowulf, King Hrothgar sat in a

great mead-hall meant to be a wonder of the world for ever; it would be his throne-room and there he would dispense his God-given goods to young and old . . . The hall towered, its gables wide and high.

To the west of the Catrail few shadows remain. The kings of the west spoke Old Welsh to their warriors and their people, and the only recognisable legacy is the persistence of their ancient place-names. Indeed the frontier marks a striking division, even on a modern map. To the west, the landscape is speckled by many Old Welsh names. The poet and novelist James Hogg farmed at Altrieve in the Yarrow Valley. The older version is Eltref, which means ‘Old Farmstead’ in early Welsh. Some names, like Berrybush, sound very English but are not. Bar y Bwlch is the correct derivation and it means ‘The Summit of the Pass’. Pen is Old Welsh for ‘head’ or ‘a high hill’ and place-names with pen abound in the western borders – Ettrick Pen, Penmanshiels, Pennygant Hill.

As the line of Catrail climbs west and up the Yarrow Valley, walkers come upon a much more substantial section. It bears an intriguing name, one which does more than hint at the purpose of the frontier. At first glance, Wallace’s Trench sounds like a reference to the famous Scottish hero of the Wars of Independence. He campaigned in the Borders and, with his force of guerrilla fighters, hid in the wastes of the Ettrick Forest before being proclaimed Guardian of Scotland at the Forest Kirk in Selkirk. But why would a guerrilla fighter have his men dig a huge trench on the hillsides of the Yarrow Valley? Siege or attritional warfare was no part of Wallace’s purpose. The historical reality is different – and fascinating.

Wallace’s Trench long predates William and indeed has nothing to do with his exploits and everything to do with his name. In such records as survive, it is variously spelled as Wallensis, Walays and Le Waleis. All of these versions mean the same thing – ‘William the Welshman’. To the great relief of many patriots, he did not come from Wales but Clydesdale in the old and half-forgotten kingdom of Strathclyde and his name probably recalls a native lineage which clung on to the old language – in other words, they continued to speak a dialect of Old Welsh into the early medieval period. Wallace’s Trench is therefore the Welshmen’s Trench, part of the long boundary between a developing English-speaking culture to the east and an ancient Celtic speech surviving in the hills to the west.

Place names support this interpretation and there is a striking clutch of them around Wallace’s Trench. One in particular suggests a military tone. Tinnis occurs four times and it derives from the Welsh dinas meaning ‘a fort’. And rising up west of the trench is Welshie’s Law, probably a blunt, later echo of old differences.

Power names places and, when the English war bands penetrated far up the Tweed and Teviot valleys, their lords reordered the map. Many Welsh place-names gave way to new English names, especially when these were centres of wealth and prestige. At Sprouston, a small village on the southern bank of the Tweed near Kelso, there was a royal English township. Some time around 657, it was visited by a great man, probably King Oswiu of Northumberland, the Overlord of Britain or Bretwalda. Sprouston is a very early English name, after a man called something like Sprow, but the fact that it was a royal settlement with a great hall speaks of consolidation and firm ownership. If the Catrail was the frontier between Celtic and English kingship in the Borders, it lay far to the west and recognised that the fertile river lands of the plains had fallen to the invader and the hill country was all that was left to the defeated.

It is possible to hold up a map of Scotland and see the faint watermark of its lost kingdoms. Long earthworks pattern the landscape, running through fields, climbing hillsides, apparently leading nowhere, and enigmatic names remember the grass-covered undulations of ancient fortresses. Again, in the Borders, there is an elaborate structure known as the Military Road. It runs for about four miles and is not a road or track but an elaborate sequence of two banks and two ditches, the deposit of tremendous and well-organised labour. Historians have conjectured its construction to the first millennium BC and believe it to be related to the great hill fort on Eildon Hill North. The Military Road seems to guard the south-western approaches to the hills, and its function may have been to slow down an attack or prevent the rapid escape of raiders laden with plunder long enough for defenders to reach it.

In Perthshire, archaeologists have uncovered the Roman frontier of the Gask Ridge, a series of watchtowers strung out in a line between Dunblane and Perth. Probably built by the legions commanded by the Governor of Britannia, Petilius Cerialis, some time around AD 73, it appears to have followed a preexisting tribal boundary. To the west and north of the Gask Ridge ruled the kings of Caledonia while, to the east, occupying Fife and Kinross, lay the territory of the Venicones. Their Latinised name has been brilliantly parsed by an American scholar and it translates as ‘the Kindred Hounds’.

Sometimes the memories of lost kingdoms are substantial, well documented and remnants survive. Strathclyde lasted until 1014 when one of its last kings, Owain, was killed in battle with the English at Carham on the banks of the Tweed and lingered almost certainly as late as 1070 when, according to one source, it was ‘violently subjugated’ by the kings of Scots. Others are little more than a few scattered fragments of a jigsaw. The kingdom of the Wildcats was undoubtedly powerful on both shores of the Moray Firth and its soldiers were willing to fight in its name as late as 1746. At Culloden, Clan Chattan fought with hopeless savagery. One of their captains, Gillies MacBean, killed fourteen government soldiers before his leg was shattered by grapeshot. When dragoons cornered the wounded man by a drystane dyke, Mac-Bean fought like a man possessed before being trampled by English horses. But who were the Wildcats? Caithness is named for them. Gaels call the Duke of Sutherland ‘Morair Chat’, his coastland ‘Machair Chat’ and the hill country ‘Monadh Chat’.

Perhaps the most amazing survival is the kingdom of Manau. Its heartland lasted until 1974 in the shape of Clackmannanshire, Scotland’s smallest county. Ignored by all but antiquaries, its talisman stands next to the old county buildings in Clackmannan. Clach na Manau is the Gaelic version of the origin name for the Stone of Manau, the core of the ancient kingdom and the derivation of Clackmannan.

These are not Ruritanian curiosities. The lost kingdoms of Scotland remember not only who we were before we thought of ourselves as Scots but, in so doing, they help unpack a much richer identity. They also remind us of political possibilities. If the Gaelic-speaking kings of Argyll had been less aggressive and less lucky, we might have lived under the rule of the Strathclyde dynasty. And we might have been worrying about the health of our native Welsh speech community or how fewer and fewer in the north were now speaking Pictish. What follows shows that Scotland was indeed never inevitable.

The Kingdom of Moray

The ancient kingdom of Moray – or Moreb, an Old Welsh name meaning ‘low-lying land by the sea’ – was much larger than the modern county of Moray. Almost certainly the descendant of the Pictish kingdom of Fidach, it extended around both shores of the Moray Firth, running from Buchan in the east, taking in the lower Spey, Inverness and the north of the Great Glen and circling north up to Caithness. Even further back in history, it encompassed the old territories of the Cat People, what became the confederacy of Clan Chattan. A kingdom centred on the sea and the firth it bordered, its southern land frontier was the Grampian massif and the point near modern Stone-haven, known as the Mounth, where the massif almost reaches the shore of the North Sea. Two kings of Moray are noted in the Icelandic sagas in the tenth century – Mael Snechtai and Mael Coluim. These are Gaelic names and scions of a vigorous dynasty. The most famous king of Moray became king of Alba or Scotland and ruled between 1040 and 1057. This was Macbeth, a much more successful ruler than Shakespeare’s drama allowed. Kings of Moray were seen as serious rivals to the line of Malcolm Canmore and, in 1130, his son, David I, mac Malcolm, finally annexed the old kingdom. He brought groups of settlers from the royal lands around the Tweed and these plantations were made on good land along the southern coasts of the Moray Firth. David I’s policy created a linguistic frontier which can still be heard today. Between Inverness and Elgin, the local accent changes noticeably. This is because those from Inverness speak English learned by their Gaelic-speaking ancestors from the recent past while those to the east came from the south in the twelfth century and were already English speakers.

2

The Faded Map

SOME TIME AROUND 320 BC, almost certainly in the benign months of the summer, a Greek explorer and scientist visited the land that would become Scotland. Pytheas had travelled an immense distance, beginning his remarkable and little-known journey at the prosperous trading colony of Massilia, modern Marseilles. He came north in search of knowledge, business opportunities and excitement. All three were recorded in On the Ocean, written on the traveller’s safe return to the warmth of the Mediterranean. This fascinating book has been lost for almost two thousand years and all knowledge of it is derived from passages used in the surviving texts of later classical authors.

None of these scholars had visited Britain or Scotland and all of them depended on Pytheas’ first-hand account. Some only included excerpts to mock him, calling him a liar and a fantasist. It was well known that human beings could not live in the hostile climate of the far north and the Greek explorer had simply made it all up. Others believed him intrepid and still more plagiarised his work without attribution. From an aggregate of all these references and some reasonable assumptions, it is possible to trace the voyage of Pytheas and even glimpse an occasional sense of what he saw.

As a serious scientist, Pytheas carried with him instruments capable of very accurate measurements and possessed enough geographical knowledge to translate his observations into data. At midday, with a cloudless sky, he could calculate the height of the sun and this allowed him to work out how far north he had travelled from Marseilles. These measurements were later expressed as latitudes and, in turn, showed where Pytheas had been when he made them. One was almost certainly recorded on the Isle of Man. From there he sailed up through the North Channel, his shipmaster no doubt avoiding the boiling tide rips off the Mull of Galloway where the Atlantic surges in to meet the Irish Sea. Likely to have hugged the coast, both to take on regular supplies of fresh water and readily find safe night anchorages (early sailors were very reluctant to travel in darkness), captains preferred to voyage in short stages. And Pytheas slowly threaded his way up through the archipelagos of the Inner and Outer Hebrides. His ship made landfall at the Point Peninsula on the eastern coast of the Isle of Lewis. That was where he made his last measurement of the sun’s height, at the northern latitude of 54 degrees and 13 minutes, somewhere near the town of Stornoway.

Gnomon

Pytheas’ ability as a mathematician was especially extraordinary when the rudimentary nature of his instruments is understood. On his epic journey to Britain, he calculated latitude on five occasions and each time he used nothing more sophisticated than a straight stick. Known as a gnomon, it was planted in the ground at an angle of precisely 90 degrees at noon, when Pytheas judged the sun to be at its zenith. If this could be done at the summer solstice, particularly when in unfamiliar territory, then so much the better. What mattered was the length of the shadow cast by the gnomon and its ratio to the height of the stick itself. Having presumably made a measurement at Marseilles or knowing what the standard ratio was, Pytheas moved north and made four more calculations. As the cast shadow lengthened slightly and the ratio to the height of the gnomon changed, Pytheas could work out degrees of latitude accurately. Working backwards from his calculations, it is possible to trace the extent of his journey. He planted his gnomon in Brittany (48 degrees north), the Isle of Man (54 degrees), the Isle of Lewis (58 degrees) and Shetland (61 degrees). The great scholar and admirer of Pytheas, Sir Barry Cunliffe, believes that the intrepid Greek probably made it as far north as Iceland (66 degrees). Gnomons are still used. The term now describes the triangular upright in the middle of a sundial.

What is even more startling was the Greek traveller’s ability to work out distances very accurately. Reproduced in the work of another, later, Greek writer, Diodorus Siculus, here is Pytheas’ general description of Britain:

Britain is triangular in shape, much as is Sicily, but its sides are not equal. The island stretches obliquely along the coast of Europe, and the point where it is least distant from the continent, we are told, is the promontory which men call Kantion [Kent] and this is about one hundred stades [19 km] from the mainland, at the place where the sea has its outlet, whereas the second promontory, known as Belerion [Land’s End], is said to be a voyage of four days from the mainland, and the last, writers tell us, extends out into the open sea and is named Orkas [Dunnet Head – opposite the Orkneys]. Of the sides of Britain the shortest, which extends along Europe, is 7,500 stades [1,400 km], the second, from the Strait to the tip [at the north] is 15,000 stades [2,800km] and the last is 20,000 stades [3,700 km] so that the entire circuit of the island amounts to 42,500 stades [7,900 km].

What astonishes all who read that passage is that Pytheas got it almost exactly right. The length of the British coastline, with all its indentations and deceptive distances is 7,580 kilometres. With only estimates of the speed of his ship, local knowledge of tides and currents to go on, he managed a level of accuracy unknown before modern times.

What is also striking is Pytheas’ sense of enterprise in venturing into the unknown, far beyond the limits of Mediterranean knowledge of north-western Europe. With characteristic precision and reticence, Herodotus had mentioned the ‘Tin Islands’ that lay somewhere in the remote northern ocean but added immediately, ‘I cannot speak with any certainty’. Tin was an essential ingredient in the alloy of bronze and, since deposits were rare along the shores of the Mediterranean, Greek merchants were always anxious to find new sources. Pytheas’ epic journey was therefore not only motivated by curiosity and an evident sense of scientific enquiry but also by the needs of commerce. Tin was very valuable and, if the mists and monsters which guarded the chilly northern seas could be avoided, there was money to be made.

Contacts already existed. Tin was being regularly traded between southern Britain and the Mediterranean in the fourth century BC but almost certainly passing through several pairs of hands on its way south. If Pytheas could discover a feasible route from Marseilles to Britain, then perhaps a chain of expensive middlemen could be cut out.

He began his long journey overland, travelling first to the port of Narbonne and, from there, was probably rowed up the River Aude as far as the draught of a boat could reach and then onwards on foot or horseback up over the watershed and down to the headwaters of the River Garonne. From there a boat would have taken Pytheas quickly and comfortably to the great estuary of the Gironde and the Atlantic coast beyond.

This and several other overland and river routes to the north were well known to the Greek colonists of Marseilles and archaeology confirms a brisk trading network exchanging Mediterranean goods for the produce of the peoples of what is now France. On the shores of the Bay of Biscay, Pytheas will have found passage on local boats plying between shore markets further up the coast or possibly with merchants from his home port or with native traders who had done business with them. No doubt he avoided travelling alone and vulnerable – perhaps he had companions whose involvement is now lost to history. In any event, passage could be rapid and, if there were no significant breaks in his journey, the explorer could have found himself in Brittany, on the southern shores of the English Channel, less than 30 days after leaving Marseilles.

Pytheas was standing on the very edge of geography. As far as he knew, no Greek had come so far north and survived to record what he saw. Certainly Cornish tin was imported but none of his compatriots had come to the place called Belerion where it was panned from streams and hacked out of shallow pits. None had seen the charcoal-burners smelt the ore into astragal-shaped ingots weighing about 80 kilograms although many had passed through the markets of Marseilles. Several of these remarkable objects have been found at various stages of their journey to the Mediterranean. They were brought to the beach market between St Michael’s Mount and Marazion on the Cornish coast, not far from Penzance. Once deals had been done and the tin loaded into boats, the rising tide refloated them and they trimmed their sails and swung away south out to sea. The sea captains navigated by pilotage, hugging the coastline, measuring progress by seamarks and crossing the Channel when the French coast came in sight, often at Cap Gris Nez.

Cost, convenience and speed dictated that a sea journey, safely managed in the summer months, was always to be preferred to the slow and dangerous business of transporting goods overland. Quantities were necessarily smaller and robbers lay in wait. When the tin ships arrived at the mouth of the Seine, the Loire or the Gironde, they travelled as far up the rivers as they could. At the point when the keels began to scrape the river bed or become clogged in mud, the 80-kilo astragals were unloaded and transferred to packhorses. Their figure-of-eight shape allowed two to be carried by each animal, slung on either side of a wooden packsaddle and lashed securely. The average packhorse could manage 160 kilos at a steady uphill walk without too much loss of condition. But these routes were only possible in summer when enough grass grew and could be grazed. Once a string of packhorses reached the banks of the River Rhône, the tin was untacked, set into boats and the current carried them quickly downstream to the sea and Marseilles.

Pytheas had travelled in the opposite direction and when he crossed the Channel, probably on a merchant ship bound for the well-known seamark of St Michael’s Mount, he was about to enter unknown waters. Most likely in short hops, he made his way up through the Irish Sea to the Isle of Man where he took his second measurement of the height of the sun (the first having been carried out in Brittany). As he moved further north the climate would have cooled noticeably, the land grown more rugged and mountainous and the maritime culture changed radically. Pytheas almost certainly found himself travelling in a very different sort of craft from what he had been used to. Here is Rufus Festus Avienus’ much later – and more poetic – version of the passage introducing Britain from On the Ocean:

Lying far off and rich in metals,

Of tin and lead. Great the strength of this nation,

Proud their mind, powerful their skill,

Trading the constant care of all.

They know not to fit with pine

Their keels, nor with fir, as use is,

They shape their boats; but strange to say,

They fit their vessels with united skins,

And often traverse the deep in a hide.

These were seagoing curraghs, not unlike those still being built in the south-west of Ireland. In 320 BC, the waters of the Irish Sea and the Atlantic shores of Scotland and Ireland would have been crossed by many curraghs, some of them very large, all of them well suited to the swells and eddies of the ocean. Curraghs were quick, easy and cheap to construct. First a frame of greenwood rods (hazel was much favoured, and willow) was driven either into the ground or into holes made in a gunwale formed into an oval. Then the rods were lashed together with cord or pine roots into the shape of a hull, upside down. Once all was tight and secure – the natural whip and tension of greenwood helped this part of the process very much – the framework was then made rigid by the fitting of benches which acted as thwarts. Over the hull hides were stretched and sewn together (or ‘united’) before being lashed to the gunwales. When the hides shrank naturally, they tightened over the greenwood rods and the seams were then caulked with wool grease or resin. Large curraghs could take twenty men or carry two tons of cargo and, since they were so straightforward to make from materials widely available, they and their small, round cousins, the coracles, would have sailed the coasts of Scotland and Ireland in their many thousands.

In his magisterial Life of St Columba, Adomnan talked of how the Iona community used curraghs to bring materials from the mainland and also described how they could be rowed and sailed. To make passage easier, the saint intervened:

[F]or on the day when our sailors had got everything ready and meant to take the boats and curraghs and tow the timbers to the island by sea, the wind, which had blown in the wrong direction for several days, changed and became favourable. Though the route was long and indirect, by God’s favour the wind remained favourable all day and the whole convoy sailed with their sails full so that they reached Iona without delay.

The second time was several years later. Again, oak trees were being towed by a group of twelve curraghs from the mouth of the River Shiel to be used here in repairs to the monastery. On a dead calm day when the sailors were having to use the oars, a wind suddenly sprang up from the west, blowing head on against them. We put in to the nearest island, called Eilean Shona, intending to stay in sheltered water.

But once again the power of the saint fixed the weather and the timbers were brought to Iona safely.

Pytheas claimed that his wanderings around Britain were not all seaborne. He travelled inland, but the hide boats will have helped him see much more than if he had gone on foot or even horseback. With a very shallow draught measured only in inches, coracles and curraghs could use rivers and lochs as their highways. Where rocky rapids or a watershed needed to be traversed, these hide boats were so light as to be easily carried. Turned upside down against the weather, they even made handy overnight shelters.

As he explored, Pytheas began to form strong but not always positive impressions of the peoples and especially the climate of the far north. Strabo, a Greek writer living in Rome after AD 14, considered On the Ocean to be little more than a catalogue of lies and exaggeration. But, in his vast, seventeen-volume Geographica, he used it nonetheless. Here is his, and Pytheas’, version of the agriculture of the communities ‘who lived near the chilly zone’:

Of the domesticated fruits and animals there is a complete lack of some and a scarcity of others, and that the people live on millet and on other herbs, fruits and roots; and where there is grain and even honey the people also make a drink from them. As for the grain, since they have no pure sunlight, they thresh it in large storehouses having first gathered the ears together there, because [outdoor] threshing floors are useless due to the lack of sun and the rain.

Some of this is little more than a Mediterranean view of long northern winters, cloudy days and the bewildering absence of several months of uninterrupted sunshine. The mention of millet is a fascinating misunderstanding. It does not grow in Britain but the reference, bracketed with ‘other herbs, fruits and roots’, is probably to Fat Hen, a nutritious plant now seen as a weed. Still known as myles or mylies in Scotland and cognate with the Latin word for millet, it was gathered, boiled and eaten as late as the eighteenth century by country people. Its seeds are rich in oil and carbohydrate and traces of Fat Hen have been found by archaeologists at sites dating back to the first millennium BC.

More generally, Pytheas was observing a society which still gathered in a harvest from wild places. In all likelihood, these were good locations for such as crab apples, hazelnuts or mushrooms and they will have been cared for and not over-picked. Our ancestors in Scotland ate – until recently – a wide range of plants now regarded as useless weeds.

Compared with Strabo’s scorn, the tone of Diodorus Siculus’ borrowings from On the Ocean is probably much closer to the original:

Britain, we are told, is inhabited by tribes who are indigenous and preserve in their way of life the ancient customs. For example they use chariots in their wars . . . and their houses are simple, being built for the most part from reeds or timbers. Their way of harvesting their grain is to cut only the heads and store them in roofed buildings, and each day they select the ripened heads and grind them, in this manner getting their food. Their behaviour is simple, very different from the shrewdness and vice that characterise the men of today. Their lifestyle is modest since they are beyond the reach of luxury which comes from wealth. The island is thickly populated, and its climate is extremely cold . . . It is held by many kings and aristocrats who generally live at peace with each other.

Once again archaeology supports Pytheas’ observations. Iron reaping hooks have been found at several sites in Scotland and the ancient method of cutting the grain near the top of the stalk is well attested into modern times. When cereals were grown in the old runrig system of long strips, the heads were cut so as to leave fodder for grazing animals. In the autumn, after the harvest, beasts came down from the summer shielings and were set on the reaped rigs to muck them, there being no other form of fertiliser. And cutting near the top also avoided the copious under-weeds of pre-industrial farming.

The last sentence of the extract from Diodorus is the first reference to British kingdoms and, although it is sketchy, even cursory, it has the virtue of simplicity. On his journeys around the coasts and inland, Pytheas clearly came across many kings and therefore many kingdoms. But Britain does not appear, at least not around the year 320 BC, to have been a squabbling anthill of competing autocrats. There were wars, the Greek explorer implied, but peace was the usual condition of life. As the nature of early Celtic kingship becomes clearer and the evidence supplied by outsiders more substantial, this observation will seem increasingly unlikely.

Pytheas noted few place-names in On the Ocean but one fascinating story was transmitted by Diodorus Siculus which hints at somewhere very specific in Scotland:

In the region beyond the land of the Celts there lies in the ocean an island no smaller than Sicily. This island . . . is situated in the north and is inhabited by the Hyperboreans who are called by that name because their home is beyond the point where the north wind blows.

Mediterranean historians were in the habit of mediating exotic customs and beliefs to their readers and listeners through more familiar terms and, when Diodorus states that Apollo was worshipped on this distant northern island, he probably meant that there was a moon cult. Worship took place in ‘a notable temple which is adorned with many votive offerings and is spherical in shape’. Diodorus goes on:

They also say that the moon, as viewed from this island, appears to be but a little distance above the earth . . . The account is also given that the god visits the island every nineteen years, the period in which the return of the stars to the same place in the heavens is accomplished . . . At the time of this appearance of the god he both plays on the lyre and dances continuously the night through from the vernal equinox until the rising of the Pleiades.

Echoes of Pythean precision can be heard clearly in this passage and the movement of the moon does, in fact, run through an 18.61-year cycle at a particular northern latitude. When it is remembered that Pytheas’ third measurement of the height of the sun was on the island of Lewis and that his calculation of 54 degrees and 13 minutes fits almost exactly with a lunar cycle of 18.61 years, the location of the spherical temple of the Hyperboreans slowly begins to come into focus.

Around 2800 BC the communities of prehistoric farmers on Lewis came together to build a spectacular temple – what is now known as the standing stones at Callanish. From the elliptical circle of outer stones, alignments run from the magnificent inner group to very particular seasonal configurations of the heavens. One aims directly at the southern moonset, another to the sunset at the equinox and a third to where the Pleiades first appear. But most telling is the fact that, every 18.61 years, the moon appears to those standing in the circle at Callanish to move along the rim of the horizon ‘dancing continuously the night through’. This transit can be seen on clear nights between the spring equinox on 21st March and 1st of May. The latter date is the great Celtic feast of Beltane, now called May Day, a celebration of fertility and awakening after the long and dead months of winter.

By the time Pytheas visited the Isle of Lewis in 320 BC, the stones at Callanish had long been abandoned and a blanket of peat was forming around them. But tales will have been told of the Old Peoples who raised them, perhaps offerings laid at the feet of the great stones, Beltane celebrated, different gods honoured. Did Pytheas’ curragh enter Loch Rog nan Ear where the stones can be seen from the sea? Did the oarsmen beach the boat at the head of the loch and did Pytheas talk to people who knew the old stories of Callanish and those who worshipped there?

Many of the ancient standing stones of the Atlantic shore were used as seamarks. North of Callanish, those sailing up the coast of Lewis could see clearly the huge Clach an Truiseal. Originally at the centre of another circle, this stone stands 5.8 metres tall and is immensely impressive. The beliefs which pulled it upright may have been long forgotten by the time Pytheas came to Lewis but it is not difficult to imagine a lingering reverence swirling around the Clach an Truiseal.

Stone circles were almost always placed carefully in the landscape, conspicuous but accessible, and, as the deposit of tremendous labour, they often retained their importance and traditions, even through periods of profound cultural change. Stonehenge still inspires powerful devotion in the twenty-first century. In Aberdeenshire, not far from Inverurie, a small but striking circle has a very interesting name. The second element of Easter Aquhorthies is a Gaelic word which means ‘Prayer Field’, a clear recognition of what took place inside the ring of huge stones. But the important issue here is chronological. Gaelic arrived in Aberdeenshire much later than the date of Easter Aquhorthies’ construction and probably millennia after the original religion of the prehistoric farmers of the Urie Valley who built it had begun to change. The gods were not the same but the traditions of reverence did not entirely fade and were understood. The stones of the Old Peoples were not fenced off and thought of as relics or monuments but were part of a changing landscape, of an aggregate of experience in one place.

Far to the south, a long way from Easter Aquhorthies and the Clach an Truiseal, another great stone circle retained all sort of significance. The Lochmaben Stane stands on the northern shore of the Solway Firth, near the outfall of the little River Sark and the modern border between England and Scotland. Pytheas probably saw it and its lost companions and, almost four centuries later, many more Mediterranean eyes looked at the huge round boulders. By AD 74, the invading Roman legions had reached Carlisle, the place called Luguvalium. Under the command of the governor of the new province of Britannia, Petilius Cerialis, soldiers built a fort on the eminence between the rivers Eden and Caldew, just to the south of their confluence. As the first professional army in European history, the Romans were methodical and, as Cerialis looked out over the grey waters of the Solway and to the flatlands beyond, his first thoughts will have been on the gathering of military intelligence. If the eagle standards were to be carried into the wilderness of the north and the legions were to march to glory behind them, then their general needed a map. As scouts rode out of the camp at Carlisle and began the long process of reconnaissance, what became Scotland began to emerge from the darkness of the past.

Markers in a largely treeless landscape will have proved invaluable and the Lochmaben Stane is huge, a granite boulder standing more than two metres high and measuring more than six metres around. Very visible on the flat Solway plain, it would have been even more impressive when Cerialis’ patrols saw it. The New Statistical Account of 1845 recorded a ring of nine large stones which enclosed a wide area of almost half an acre. Seven had been removed by the farmer at Old Graitney just before 1845 to allow him to plough more ground and an eighth had been dug out and rolled into a nearby hedge. Recent examination of the remaining megalith (almost certainly too big to shift) gave a date of around 2525 BC. And, when the Roman scouts rode north and west from Carlisle, the old circle was already ancient, still venerated and very useful.

Over the four centuries of Roman Britain, the first maps made for Petilius Cerialis and his fellow governors of the province of Britannia were added to and refined. Much later, in the seventh century AD, a clerk working at the Italian town of Ravenna used them to compile a composite map of Britain (and much of the known world) and he attached two place-names to the area. Locus Maponi supplies the initial elements of the name of the old stone circle but it was almost certainly more precisely applied to the town of Lochmaben ten miles to the north-west and, by extension, to the district between it and the Solway. Locus Maponi does not mean the ‘Place of Mapon or Maben’ but ‘the Loch’ or ‘Pool’ and, at Lochmaben, there are three. The Castle Loch is larger than the Kirk Loch and the Mill Loch is the smallest.

Mapon or Maponus was a god. His name derives from the Old Welsh root, map, which meant ‘son of’ and the predominant image is of a divine youth. Strong evidence of a local cult of Mapon has been found in a series of dedications at the slightly later Roman forts of the first century AD at Birrens, Brampton, Chesterholm (Vindolanda), Ribchester and the settlement at Corbridge. Most twin the Celtic god with Apollo and, as at Callanish, both may be further associated with memories of a moon cult at the stone circle on the Solway.

In the first millennium BC, Celtic beliefs were also associated with sacred water sites, especially small lochs. Having damaged it in some ritual manner, priests threw metalwork into watery places, probably as a means of propitiating potentially malevolent gods. And it may be that the lochs at Lochmaben were particularly sacred to Mapon and expensive swords, shields and other metal artefacts were deposited there. By contrast, the stone circle at the seashore may have directed worship to the sky and the transit of the heavens, perhaps to the moon. Although worship at each site probably did not occur even in the same millennium, there is a sense of a sacred landscape, the land of the people of Maben.

The clerk at Ravenna marked down another local name. Maporitum certainly denotes the stone circle for its meaning is clear. The ford of Mapon was still in regular use in the nineteenth century and, in fact, it gave its name to the Solway Firth. Ancient geography encouraged travellers, armies and anyone else on foot to cross the firth by one of three fords if they wanted to avoid a long detour to the east. Solway Moss and the boggy, shifting wetlands between the mouths of the rivers Esk and Sark could be treacherous and the more reliable bed of the firth was usually preferred. There were low-tide crossings between Annan and Bowness, at the Sandy Wath between Torduff Point and the shore near Drumburgh and finally at what was known as the Sul Wath. The Vikings brought the word wath (cognate to ‘wade’) and it now exists in Scots and Cumbrian meaning ‘a ford’. The sul was the pillar or the standing stone and it referred to the Lochmaben Stane. It marked the northern terminus of the shortest of the Solway (or Sulvath) fords and, in an otherwise featureless, flat land- and seascape, it was a vital aid to navigation. Travellers from the south anxious not to stray into deeper water kept their eyes fixed on the great stone.

Petilius Cerialis and his staff officers were not entirely ignorant about what lay north of Carlisle. From Pytheas, his imitators and detractors, they knew that Britain was a large island and that another, smaller island lay to the west. More information had been compiled by a Spanish geographer, Pomponius Mela. Writing just before the invasion of Britain in AD 43 by the armies of the Emperor Claudius, he also produced a map which shows Britain and Ireland in schematic outline, just as Pytheas had described it and in roughly the correct place in relation to mainland Europe. Significantly, Mela was the first to plot the location of the islands named as the Orcas in On the Ocean. Using the slightly different form of the Orcades, he places the archipelago off the northernmost point of Britain. There are thirty islands in the Orcades, according to Mela, and, not far to the west, he sets the Haemodes, the Shetlands. There are only seven of these. The arithmetic is not unreasonable and speaks of enquiries made, perhaps even at first hand, of people who had been there.

Ultima Thule

This was the phrase used by the Greeks, the Romans and Dark Ages’ scholars to mean ‘Farthest North’, the frozen edge of the known world. Pytheas reckoned Thule to be six days’ sail north of Britain and Pliny the Elder wrote that, in midsummer, there was no night and, in midwinter, no day. The word probably derives from the Greek tholos meaning ‘murky’ or ‘indistinct’. It all added to the sense of mystery about the far north. When Ptolemy made his famous map of Britain, he turned Scotland north of the Tay through a 90-degree angle so that it bent abruptly to the east. The problem for Ptolemy was that, if he had plotted the north of Britain correctly, it would have extended to a latitude of 66 degrees north and, from the vantage point of the sun-drenched Mediterranean, the Greeks did not believe that human beings could survive north of 63 degrees. The inhabitants of Scotland’s Atlantic coasts and islands were closer to the truth in every way. When they heard the call of the whooper swans and looked up at their V-shaped squadrons migrating north in the spring, they knew that there was land in the north. The great eighth-century historian, Bede, believed that Thule was Iceland and, a hundred years later, Dicuil, an Irish monk at the court of Charlemagne, described the long summers and winters of the north and the frozen seas beyond Iceland. Ultima Thule, ‘Farthest North’, turned out to be the vast subcontinent of Greenland and, when Viking longships sailed into its summer landing places, those classical writers who mocked Pytheas were once again proved wrong.