35,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: John Wiley & Sons

- Kategorie: Religion und Spiritualität

- Sprache: Englisch

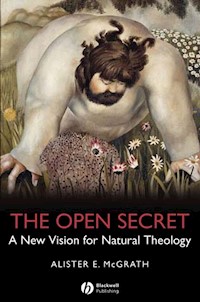

Natural theology, in the view of many, is in crisis. In this long-awaited book, Alister McGrath sets out a new vision for natural theology, re-establishing its legitimacy and utility.

- A timely and innovative resource on natural theology: the exploration of knowledge of God as it is observed through nature

- Written by internationally regarded theologian and author of numerous bestselling books, Alister McGrath

- Develops an intellectually rigorous vision of natural theology as a point of convergence between the Christian faith, the arts and literature, and the natural sciences, opening up important possibilities for dialogue and cross-fertilization

- Treats natural theology as a cultural phenomenon, broader than Christianity itself yet always possessing a distinctively Christian embodiment

- Explores topics including beauty, goodness, truth, and the theological imagination; how investigating nature gives rise to both theological and scientific theories; the idea of a distinctively Christian approach to nature; and how natural theology can function as a bridge between Christianity and other faiths

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 710

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2011

Ähnliche

Contents

Acknowledgment

CHAPTER 1 Natural Theology: Introducing an Approach

“Nature” is an Indeterminate Concept

Natural Theology is an Empirical Discipline

A Christian Natural Theology Concerns the Christian God

A Natural Theology is Incarnational, Not Dualist

Resonance, Not Proof: Natural Theology and Empirical Fit

Beyond Sense-Making: The Good, the True, and the Beautiful

PART I The Human Quest for the Transcendent

CHAPTER 2 The Persistence of the Transcendent

Natural Theology and the Transcendent

The Triggers of Transcendent Experiences

The Transcendent and Religion

CHAPTER 3 Thinking About the Transcendent: Three Recent Examples

Iris Murdoch: The Transcendent and the Sublime

Roy Bhaskar: The Intimation of Meta-Reality

John Dewey: The Curious Plausibility of the Transcendent

CHAPTER 4 Accessing the Transcendent: Strategies and Practices

Ascending to the Transcendent from Nature

Seeing the Transcendent Through Nature

Withdrawing from Nature to Find the Transcendent Within Oneself

Discerning the Transcendent in Nature

CHAPTER 5 Discernment and the Psychology of Perception*

Perception is Brain-Based

Perception Involves Dynamic Mental Structures

Perception is Egocentric and Enactive

Perception Pays Attention to Significance

Perception Can Be Modulated by Motivation and Affect

Human Perception and Natural Theology

Conclusion to Part I

PART II The Foundations of Natural Theology

CHAPTER 6 The Open Secret: The Ambiguity of Nature

The Mystery of the Kingdom: Jesus of Nazareth and the Natural Realm

The Levels of Nature: The Johannine “I am” Sayings

Gerard Manley Hopkins on “Seeing” Nature

CHAPTER 7 A Dead End? Enlightenment Approaches to Natural Theology

The Enlightenment and its Natural Theologies: Historical Reflections

The Multiple Translations and Interpretations of the “Book of Nature”

The Flawed Psychological Assumptions of the Enlightenment

The Barth–Brunner Controversy (1934) and Human Perception

Enlightenment Styles of Natural Theology: Concluding Criticisms

CHAPTER 8 A Christian Approach to Natural Theology

On “Seeing” Glory: The Prologue to John’s Gospel

A Biblical Example: The Call of Samuel

The Christian Tradition as a Framework for Natural Theology

Natural Theology and a Self-Disclosing God

Natural Theology and an Analogy Between God and the Creation

Natural Theology and the Image of God

Natural Theology and the Economy of Salvation

Natural Theology and the Incarnation

Conclusion to Part II

PART III Truth, Beauty, and Goodness: An Agenda for a Renewed Natural Theology

CHAPTER 9 Truth, Beauty, and Goodness: Expanding the Vision for Natural Theology

CHAPTER 10 Natural Theology and Truth

Resonance, Not Proof: Natural Theology and Sense-Making

The Big Picture, Not the Gaps: Natural Theology and Observation of the World

Natural Theology, Counterintuitive Thinking, and Anthropic Phenomena

Natural Theology and Mathematics: A “Natural” Way of Representing Reality

Truth, Natural Theology, and Other Religious Traditions

On Retrieving the Richness of Truth

Truth and a Natural Theology of the Imagination

CHAPTER 11 Natural Theology and Beauty

Recovering the Place of Beauty in Natural Theology

The Neglect of Beauty The “Deconversion” of John Ruskin

Hugh Miller on the Aesthetic Deficiencies of Sense-Making

John Ruskin and the Representation of Nature

The Beauty of Theoretical Representations of Nature

Beauty, Awe, and the Aesthetic Engagement with Nature

Aesthetics and the “Seeing” of Beauty

Beauty, Natural Theology, and Christian Apologetics

CHAPTER 12 Natural Theology and Goodness

The Moral Vision of Reality

Natural Theology and Natural Law

The Eternal Return of Natural Law

The Moral Ambivalence of Nature

The Knowability of Goodness in Nature

The Discernment of Goodness: The Euthyphro Dilemma

Conclusion to Part III

CHAPTER 13: Conclusion

Bibliography

Index

© 2008 by Alister E. McGrath

BLACKWELL PUBLISHING

350 Main Street, Malden, MA 02148-5020, USA

9600 Garsington Road, Oxford OX4 2DQ, UK

550 Swanston Street, Carlton, Victoria 3053, Australia

The right of Alister E. McGrath to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the UK Copyright, Designs, and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, except as permitted by the UK Copyright, Designs, and Patents Act 1988, without the prior permission of the publisher.

Designations used by companies to distinguish their products are often claimed as trademarks. All brand names and product names used in this book are trade names, service marks, trademarks, or registered trademarks of their respective owners. The publisher is not associated with any product or vendor mentioned in this book.

This publication is designed to provide accurate and authoritative information in regard to the subject matter covered. It is sold on the understanding that the publisher is not engaged in rendering professional services. If professional advice or other expert assistance is required, the services of a competent professional should be sought.

First published 2008 by Blackwell Publishing Ltd

2 2008

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

McGrath, Alister E., 1953–

The open secret: a new vision for natural theology/Alister E.

McGrath.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-4051-2692-2 (hardcover: alk. paper)—ISBN 978-1-4051-2691-5

(pbk.: alk. paper) 1. Theism. 2. Natural theology. 3. Nature—Religious aspects—Christianity. I. Title.

BL200.M35 2008

211′.3—dc22

2007041410

The publisher’s policy is to use permanent paper from mills that operate a

sustainable forestry policy, and which has been manufactured from pulp

processed using acid-free and elementary chlorine-free practices. Furthermore,

the publisher ensures that the text paper and cover board used have met

acceptable environmental accreditation standards.

For further information on

Blackwell Publishing, visit our website at

www.blackwellpublishing.com

I seem to have been only like a boy playing on the sea-shore, and diverting myself in now and then finding a smoother pebble or a prettier shell than ordinary, whilst the great ocean of truth lay all undiscovered before me.

Isaac Newton (1643–1727)

The greatest thing a human soul ever does in this world is to see something, and tell what it saw in a plain way... To see clearly is poetry, prophecy, and religion – all in one.

John Ruskin (1819–1900)

Additional praise for The Open Secret

“For much of the twentieth century natural theology was regarded as intellectually moribund and theologically suspect. In this splendid new book, bestselling author and distinguished theologian Alister McGrath issues a vigorous challenge to the old prejudices. Building on the foundation of the classical triad of truth, beauty, and goodness, he constructs an impressive case for a new and revitalized natural theology. This is a well-conceived, timely, and thoughtprovoking volume.”

Peter Harrison, Harris Manchester College, Oxford

Acknowledgments

It is a pleasure to be able to acknowledge those who have contributed to the writing of this volume. My greatest debt by far is to Joanna Collicutt, who was my research assistant on this project, and is now lecturer in the psychology of religion at Heythrop College, London University. Her research for this work focused on John Ruskin, John Dewey, and the biblical material, particularly the call of Samuel, the parables of Jesus, and the Johannine “I am” sayings. She provided expert advice on the psychology of religion, and authored chapter 5, dealing with the cognitive neuropsychology of perception, and some portions of other chapters. She also proposed the title of this work.

I also acknowledge financial support from the John Templeton Foundation, without which this work could never have been written. The argument and approach of this book have been shaped, in part, through significant conversations with Justin Barrett, John Barrow, John Hedley Brooke, Simon Conway Morris, Paul Davies, Daniel Dennett, Robert McCauley, and Thomas F. Torrance. While these scholars may not agree with the approach I have taken in this work, it is appropriate to acknowledge their kindness in discussing some key issues relating to natural theology, and the significance of their views in shaping my analysis of critical questions. I remain completely responsible for errors of fact or judgment in this work.

This work represents a substantially expanded version of the 2008 Riddell Memorial Lectures at Newcastle University, England. It also includes material originally delivered as the 2005 Mulligan Sermon at Gray’s Inn, and the 2006 Warburton Lecture at Lincoln’s Inn. I am grateful to both these ancient London Inns of Court for their invitations to speak on the theme of theology and the law, and their kind hospitality. My thanks also to Michelle Edmonds, who suggested the cover illustration for the book; to Jenny Roberts, for her skill as a copyeditor; and to Rebecca Harkin of Blackwell Publishing, for her encouragement and patience as this work gradually took shape.

Alister McGrath

Oxford, June 2007

CHAPTER 1

Natural Theology: Introducing an Approach

The heavens are telling the glory of God;

and the firmament proclaims his handiwork.

Day to day pours forth speech,

and night to night declares knowledge.

(Psalm 19: 1)

When I look at your heavens, the work of your fingers,

the moon and the stars that you have established;

what are human beings that you are mindful of them,

mortals that you care for them?

(Psalm 8: 3–4)

For as the heavens are higher than the earth,

so are my ways higher than your ways

and my thoughts than your thoughts.

(Isaiah 55: 9)

These familiar words from the Hebrew Scriptures characterize the entire enterprise of natural theology: they affirm its possibility, while pointing to the fundamental contradictions and tensions that this possibility creates. If the heavens really are “telling the glory of God,”1 this implies that something of God can be known through them, that the natural order is capable of disclosing something of the divine. But it does not automatically follow from this that human beings, situated as we are within nature, are capable unaided, or indeed capable under any conditions, of perceiving the divine through the natural order. What if the heavens are “telling the glory of God” in a language that we cannot understand? What if the glory of God really is there in nature, but we cannot discern it?

Natural theology can broadly be understood as the systematic exploration of a proposed link between the everyday world of our experience2 and another asserted transcendent reality,3 an ancient and pervasive idea that achieved significant elaboration in the thought of the early Christian fathers,4 and continues to be the subject of much discussion today. Yet it is essential to appreciate that serious engagement with natural theology in the twenty-first century is hindered both by a definitional miasma, and the lingering memories of past controversies, which have created a climate of suspicion concerning this enterprise within many quarters. As Christoph Kock points out in his excellent recent study of the fortunes of natural theology within Protestantism, there almost seems to be a presumption in some circles that “natural theology” represents some kind of heresy.5

The lengthening shadows of half-forgotten historical debates and cultural circumstances have shaped preconceptions and forged situation-specific approaches to natural theology that have proved singularly ill-adapted to the contemporary theological situation. The notion of “natural theology” has proved so conceptually fluid, resistant to precise definition, that its critics can easily present it as a subversion of divine revelation, and its supporters, with equal ease, as its obvious outcome. Instead of perpetuating this unsatisfactory situation, there is much to be said for beginning all over again, in effect setting aside past definitions, preconceptions, judgments, and prejudices, in order to allow a fresh examination of this fascinating and significant notion.

This book sets out to develop a distinctively Christian approach to natural theology, which retrieves and reformulates older approaches that have been marginalized or regarded as outmoded in recent years, establishing them on more secure intellectual foundations. We argue that if nature is to disclose the transcendent, it must be “seen” or “read” in certain specific ways – ways that are not themselves necessarily mandated by nature itself. It is argued that Christian theology provides an interpretative framework by which nature may be “seen” in a way that connects with the transcendent. The enterprise of natural theology is thus one of discernment, of seeing nature in a certain way, of viewing it through a particular and specific set of spectacles.

There are many styles of “natural theology,” and the long history of Christian theological reflection bears witness to a rich diversity of approaches, with none achieving dominance – until the rise of the Enlightenment. As we shall see, the rise of the “Age of Reason” gave rise to a family of approaches to natural theology which asserted its capacity to demonstrate the existence of God without recourse to any religious beliefs or presuppositions. This development, which reflects the Enlightenment’s emphasis upon the autonomy and sovereignty of unaided human reason, has had a highly significant impact on shaping Christian attitudes to natural theology. Such has been its influence that, for many Christians, there is now an automatic presumption that “natural theology” designates the enterprise of arguing directly from the observation of nature to demonstrate the existence of God.

This work opposes this approach, arguing for a conceptual redefinition and methodological relocation of natural theology. Contrary to the Enlightenment’s aspirations for a universal natural theology, based on common human reason and experience of nature, we hold that a Christian natural theology is grounded in and informed by a characteristic Christian theological foundation. A Christian understanding of nature is the intellectual prerequisite for a natural theology which discloses the Christian God.

Christianity brings about a redefinition of the “natural,” with highly significant implications for a “natural theology.” The definitive “Christ event” as interpreted by the distinctive and characteristic Christian doctrine of the incarnation can be said to redeem the category of the “natural,” allowing it to be seen in a new way. In our sense, a viable “natural theology” is actually a “natural Christian theology,” in that it is shaped and made possible by the normative ideas of the Christian faith. A properly Christian natural theology points to the God of the Christian faith, not some generalized notion of divinity detached from the life and witness of the church.6

The notion of Christian discernment – of seeing things in the light of Christ – is frequently encountered throughout the New Testament. Paul urges his readers not to “be conformed to this world,” but rather to “be transformed by the renewing of your minds” (Romans 12: 2) – thus affirming the capacity of the Christian faith to bring about a radical change in the way in which we understand and inhabit the world.7

The New Testament uses a wide range of images to describe this change, many of which suggest a change in the way in which we see things: our eyes are opened, and a veil is removed (Acts 9: 9–19; 2 Corinthians 3: 13–16). This “transformation through the renewing of the mind” makes it possible to see and interpret things in a new way. For example, the Hebrew Scriptures came to be understood as pointing beyond their immediate historical context to their ultimate fulfillment in Christ.8 In a similar way the world comes to be seen as pointing beyond the sphere of everyday experience to Christ its ultimate creator.9

A Christian natural theology is thus about seeing nature in a specific manner, which enables the truth, beauty, and goodness of God to be discerned, and which acknowledges nature as a legitimate, authorized, and limited pointer to the divine. There is no question of such a natural theology “proving” the existence of God or a transcendent realm on the basis of pure reason, or seeing nature as a gateway to a fully orbed theistic system.10 Rather, natural theology addresses fundamental questions about divine disclosure and human cognition and perception. In what way can human beings, reflecting on nature by means of natural processes, discern the transcendent?

This book represents an essay – in the classic French sense of essai, “an attempt” – to lay the ground for the renewal and revalidation of natural theology, fundamentally as a legitimate aspect of Christian theology, but also as a contribution to a wider cultural discussion. Natural theology touches some of the great questions of philosophy, and hence of life. What can we know? What does what we know suggest about reality itself? How does this affect the way we behave and what we can become? These questions refuse to be restricted to the realms of academic inquiry, in that they are of relevance to culture as a whole.

The book thus sets out to re-examine the entire question of the intellectual foundations, spiritual utility, and conceptual limits of natural theology. Such a task entails a critical examination of the present state of the debate, but also rests on a historical analysis. Crucial to this is the observation that the definition of natural theology was modified in the eighteenth century in order to conform to the Enlightenment agenda. As a result, natural theology has come to be understood primarily as a somewhat unsuccessful attempt to prove the existence of God on the basis of nonreligious considerations, above all through an appeal to “nature.”

The book is broken down into three major parts. It opens by considering the perennial human interest in the transcendent, illustrating its persistence in supposedly secular times, and describing the methods and techniques that have emerged as humanity has attempted to rise above its mundane existence, encountering something that is perceived to be of lasting significance and value. This is correlated with contemporary understandings of the psychology of perception.

The second part moves beyond the general human quest for the transcendent, and sets this in the context of an engagement with the natural realm that is sustained and informed by the specific ideas of the Christian tradition. Natural theology is here interpreted, not as a general search for divinity on terms of our own choosing, but as an engagement with nature that is conducted in the light of a Christian vision of reality, resting on a trinitarian, incarnational ontology. This part includes a detailed exploration of the historical origins and conceptual flaws of the family of natural theologies which arose in response to the Enlightenment, which dominated twentieth-century discussion of the matter.

The third and final part moves beyond the concept of natural theology as an enterprise of sense-making, offering a wider and richer vision of its tasks and possibilities. It is argued that rationalist approaches to natural theology represent an attenuation of its scope, reflecting the lingering influence of the agendas and concerns of the “Age of Reason.” Natural theology is to be reconceived as involving every aspect of the human encounter with nature – rational, imaginative, and moral.

In that this volume offers a new approach which poses a challenge to many existing conceptions of the nature and possibilities of natural theology, in what follows we shall set out a brief account of its leading themes, which will be expanded and extended in subsequent chapters.

“Nature” is an Indeterminate Concept

The concept of natural theology that became dominant in the twentieth century is that of proving the existence of God by an appeal to the natural world, without any appeal to divine revelation. Natural theology has come to be understood, to use William Alston’s helpful definition, as “the enterprise of providing support for religious beliefs by starting from premises that neither are nor presuppose any religious beliefs.”11 The story of how this specific understanding of natural theology achieved dominance, marginalizing older and potentially more productive approaches, is itself of no small interest.12 One of the major pressures leading to this development was the growing influence of the Enlightenment, which placed Christian theology under increasing pressure to offer a demonstration of its core beliefs on the basis of publicly accepted and universally accessible criteria – such as an appeal to nature and reason.

The “Age of Reason” tended to the view that the meaning of the term “nature” was self-evident. In part, the cultural triumph of the rationalist approach to natural theology in the eighteenth century rested on a general inherited consensus that “nature” designated a reasonably well-defined entity, capable of buttressing philosophical and theological reflection without being dependent on any preconceived or privileged religious ideas. The somewhat generic notions of “natural religion” or “religion of nature,” which became significant around this time, are themselves grounded in the notion of a universal, objective natural realm, open to public scrutiny and interpretation.13

It is easy to understand the basis of such a widespread appeal to nature in the eighteenth century. On the one hand, Enlightenment writers looking for a secure universal foundation of knowledge, free of political manipulation or ecclesiastical influence, regarded nature as a potentially pure and unsullied source of natural wisdom.14 On the other, Christian apologists anxious to meet increasing public skepticism about the reliability of the Bible as a source of divine revelation were able to shore up traditional beliefs concerning God through an appeal to nature.15

Relatively recent developments, however, have undermined the foundations of this older approach. Critical historical scholarship has suggested that the Enlightenment is more variegated and heterogeneous than an earlier generation of scholars believed,16 making it problematic to speak of “an Enlightenment natural theology,” as if this designated a single, well-defined entity. It is increasingly clear that the Enlightenment itself mandated a number of approaches to nature, even if these share some common themes.

Perhaps more significantly, the notion of “nature” proves to be rather more fluid than the Enlightenment appreciated. An extended engagement with the natural world leads to the insight that the terms “nature” and “the natural,” far from referring to objective, autonomous entities, are conceptually malleable notions, patient of multiple interpretations – none of which is self-evident. Since World War II, there has been an increasing awareness that “nature” is essentially a constructed concept.17 Concepts of nature and the natural – note the deliberate use of the plural – are themselves the outcome of a process of interpretation and evaluation, influenced by the social situation, vested interests, and agendas of those with power and status.18 In the twentieth century, prevalent and influential ways of “seeing” nature have included:

Nature as a mindless force, causing inconvenience to humanity, and demanding to be tamed;

Nature as an open-air gymnasium, offering leisure and sports facilities to affluent individuals who want to demonstrate their sporting prowess;

Nature as a wild kingdom, encouraging scuba-diving, hiking, and hunting;

Nature as a supply depot – an aging and increasingly reluctant provider which produces (although with growing difficulty) minerals, water, food, and other services for humanity.19

These views of nature are not simply different; they are inconsistent with each other, their respective accentuations reflecting the different agendas of those who devised them in the first place. Nature, far from being a constant, robust, autonomous entity, is an intellectually plastic notion. Definitions of nature may well tell us more about those who define it than what it is in itself.20

Natural Theology is an Empirical Discipline

One of the distinctive features of our approach to natural theology is the view that, while philosophical and theological reflection on the issues attending it are important, empirical questions cannot be avoided. For example, consider James Barr’s excellent summary of traditional definitions of natural theology:

Traditionally, “natural theology” has commonly meant something like this: that “by nature,” that is, just by being human beings, men and women have a certain degree of knowledge of God and awareness of him, or at least a capacity for such awareness; and this knowledge or awareness exists anterior to the special revelation of God made through Jesus Christ, through the Church, through the Bible.21

This account provokes several fundamental and related questions about nature in general, and about humannature in particular. What does it mean “just” to be “human beings”? How can “knowledge of God” be calibrated? How can the “capacity” for an “awareness of God” be explored? And what are the implications for the reformulation of a natural theology?

These are questions about human psychology at least as much as they are questions of systematic theology or metaphysics. In this book, we shall take the psychological perspectives of this matter with the greatest seriousness, considering the processes by which human beings make sense of their environments. The influence of Enlightenment rationalism until recently has been such that natural theology has been understood primarily as an exercise in which human observers were able to read nature simply and objectively from a position of privilege. Yet the characteristic modernist notion that human observers are detached from nature has been called into question by the growing recognition in psychology that cognition is an embodied, situated activity of sense-making. Human beings are part of the natural order which they observe and interpret. Any notion of the “objectivity” of human interpretations of nature is undermined by the very nature of the psychological processes by which observation takes place. These considerations do not discredit the notion of natural theology itself; they do, however, cause severe difficulties for the particular approach to natural theology which emerged during the period of the Enlightenment.

It is to be recognized that the human observer is not a passive spectator but an active interpreter of the natural world. A deepening understanding of the psychology of human cognition is the occasion for a retrieval of Judeo-Christian accounts of our engagement with the world which recognize that humanity actively constructs a vision of reality.22 This is consistent with a “critical realist” epistemology, which affirms both the existence of an extra-mental reality and the active, constructive role of the observer in representing and interpreting it.23 While this could be argued to be consistent with a social constructivist position, which holds that human subjectivity imposes itself on what we mistakenly believe to be objective,24 critical realism insists that human thought is constrained and informed by an engagement with an external reality. Where social constructivism holds that the vision of reality that humans construct reflects the outcome of human autonomy and creativity, rather than any “order of things” within nature itself, our approach insists that the human attempt to make sense of things is shaped by the way things actually are.

A Christian Natural Theology Concerns the Christian God

The quest for a viable Christian natural theology can be positioned against a continuing cultural interest in the transcendent. In a penetrating analysis of the failure of the Enlightenment to eliminate religion in the West, the Polish philosopher Leszek Kolakowski argues that the renewal of interest in the transcendent is indicative of the inner contradictions and vulnerabilities within Western culture. The “return of the sacred,” he argues, is a telling sign of the failure of the ersatz Enlightenment “religion of humanity,” in which a deficient “godlessness desperately attempts to replace the lost God with something else.”25 Natural theology is to be set within this general cultural context of continuing interest and yearning for the transcendent. There is a widespread concern to engage with the empirical world of everyday experience in such a way that it can point to the existence of the transcendent, disclose its character, or possibly lead into its presence.

For the Christian this quickly leads to a further thought: does a quest for the transcendent through nature lead to the God of Christianity – a trinitarian God, who became incarnate in Jesus Christ? It is no idle question. As we shall see, the British philosopher Iris Murdoch insisted upon the foundational role of the transcendent in any attempt to sustain the notion of “the good” (pp. 291–2). Yet Murdoch regarded herself as an atheist. The quest for the transcendent does not necessarily entail belief in a god or plurality of gods.

Even those who do hold that the quest for the transcendent leads to belief in a single divinity would question whether this is necessarily to be identified with the God of Christianity. As we noted earlier, the Boyle lectures are widely regarded as the most significant public assertion of the “reasonableness” of Christianity in the early modern period. These lectures set out to demonstrate that there was a direct, publicly persuasive connection between nature and the Christian God in response to that age’s growing emphasis upon rationalism and its increasing suspicion of ecclesiastical authority.26

Yet by the end of the eighteenth century, the lectures were widely regarded as discredited. In part, this was due to growing skepticism concerning their intellectual merits. “As the eighteenth century progressed, the ‘reasonable’ Christianity of the Boyle lecturers came to look increasingly flimsy and vulnerable.”27 Yet perhaps more seriously, this approach seemed to have an inbuilt tendency to lead to heterodox, rather than orthodox, forms of Christianity.28

Thus, while we would argue that a Christian natural theology has the potential to shed light on the cultural phenomenon of the desire to find the transcendent in nature, it seems that the quest for the transcendent in nature has not automatically led to the Christian God.

In contrast, the present study adopts a specifically Christian approach to natural theology from the outset, anchoring it in the Christ event. This is a book about natural Christian theology, which interprets natural theology as something that is both historically located in the life and death of Jesus of Nazareth and theologically interpreted by the church. This theology places the general questions about nature and human nature in the specific context of the gospel of Jesus Christ. As already noted, its central claim is that the Christ event renders all theology “natural” because in it the natural order is redeemed. The basis of such a “natural Christian theology” is ultimately the doctrine of the incarnation.

A Christian natural theology is thus undertaken on the basis of a Christian vision of God and nature, which are in turn focused on the person of Christ. This approach to natural theology allows nature to be “seen” in the light of the Christian tradition. That tradition raises certain significant questions concerning both the observer, and what is being observed. What if nature is “fallen” – to note a concern we shall consider in more detail later – so that its capacity to disclose God is diminished or distorted? Or if human observers and interpreters of nature share its fallenness, entailing a double diminution or distortion of the glory of God? This point cannot be evaded by a selective reading of nature, which accentuates its beauty and orderedness, while disregarding its more ugly, chaotic aspects, particularly as seen in natural evil and suffering. A robust theological framework is thus essential if nature is to be engaged with coherently as an entirety, rather than adopting a highly eclectic, piecemeal approach to its interpretation.

A Natural Theology is Incarnational, Not Dualist

Many traditional approaches to natural theology presuppose an essentially dualist framework. An implicit assumption of ontological bipolarity underlies the affirmation that the transcendent can be accessed via the mundane, the eternal through the temporal, or the supernatural through the natural. As Thomas F. Torrance has pointed out, such dualist assumptions are deeply ingrained within the Western theological tradition, and can be argued to reflect the influence of speculative Hellenistic philosophy rather than its original Jewish intellectual context.29 Yet a Christian natural theology does not necessarily presuppose any such dualism or set of bipolarities. Nature and supernature are not to be thought of as two separate worlds, but as different expressions of the same reality.30

The Christian doctrine of the incarnation forces re-evaluation of such dichotomies, offering a new understanding of nature. As Greek patristic writers constantly emphasized, the pattern of creation, incarnation, and redemption was about the transformation of the entire category of the “natural,” not merely about the redemption and renewal of human nature as one element, however important, of that domain.31 The doctrine of the incarnation affirms the capacity of the natural to disclose the divine, both on account of its status as the divine creation, and as the object of God’s habitation. This point was stressed by John of Damascus, in his controversy with those who held that material or physical objects could not be vehicles of divine disclosure or revelation.32 God’s decision to inhabit the material order in and through the incarnation affirms its God-bestowed – though not inevitable or automatic – capacity to reveal the divine.

Resonance, Not Proof: Natural Theology and Empirical Fit

As noted earlier, natural theology is widely understood to be “the enterprise of providing support for religious beliefs by starting from premises that neither are nor presuppose any religious beliefs” (William Alston).33 Alston’s definition clearly identifies the apologetic intention of traditional approaches to natural theology. As we noted earlier, the Boyle Lectures assumed that natural theology offered proofs for the existence of God. Starting from nature, the existence of God is invoked as the only way of making sense of what is observed. For many of the early Boyle lecturers, the complexity and beauty of the physical world could only be explained on the basis of the existence of a creator God. For William Paley, author of the highly influential Natural Theology (1802),34 the close observation of the biological world demanded a similar conclusion. Nature was to be compared to a watch, whose complex mechanism pointed to the existence of a divine watchmaker. While some of these writers saw their arguments as constituting “proofs” for God’s existence, they are perhaps better seen as a retrospective validation of belief in God. This point underlies John Henry Newman’s lapidary remark: “I believe in design because I believe in God; not in God because I see design.”35

The approach to natural theology set out in this volume also has considerable apologetic potential. Nature is here interpreted as an “open secret” – a publicly accessible entity, whose true meaning is known only from the standpoint of the Christian faith.36 This rests, however, not upon an attempt to “prove” the existence of God from observation of nature, but upon the capacity of the Christian worldview to comprehend what is observed, including the human capacity to make sense of things. The explanatory fecundity of Christianity is affirmed, in that it is seen to resonate with what is observed. “I believe in Christianity as I believe that the Sun has risen – not only because I see it, but because by it, I see everything else.”37 These concluding words of C. S. Lewis’s paper “Is theology poetry?” set out the Christian view that belief in God illuminates the intellectual landscape, allowing things to be seen in their true perspective, so that the inner coherence of reality may be appreciated.

On this approach, apologetics is grounded in the resonance of worldview and observation, with the Christian way of seeing things being affirmed to offer a robust degree of empirical fit with what is actually observed – the “best explanation” of a complex and multifaceted phenomenon.38 This basic approach can be seen in John Polkinghorne’s discussion of the capacity of various worldviews to make sense of various aspects of reality, using four criteria of excellence: economy, scope, elegance, and fruitfulness. Polkinghorne here invokes theism as a more powerful explanatory tool than naturalism, and holds that a trinitarian theism is superior to a more generic theism in this respect.39

This approach is also found in the writings of Richard Dawkins, who argues that the best degree of empirical fit with observation is obtained, in the first place, through a Darwinian account of the evolution of species, and in the second, by the rejection of any notion of God, or of any concept of purpose within the natural order. “The universe we observe has precisely the properties we should expect if there is, at bottom, no design, no purpose, no evil and no good, nothing but blind pitiless indifference.”40

This is not about “proof,” understood as a logically watertight demonstration, or the unambivalent closure of a scientific debate on the basis of an unassailable evidential basis.41 Rather, it speaks of the “best explanation,” as defined in terms of the convergence of theory and observation. Nature, as we have emphasized, is open to multiple interpretations. While each of those interpretations is underdetermined by the evidence,42 it offers its own individual way of accounting for nature, which resonates to a greater or lesser extent with nature as experienced. The relevance of this to a reformulated natural theology will be clear. Where an earlier generation might have thought it could “prove” the existence of God by reflection on nature, this approach to natural theology holds that nature reinforces an existing belief in God through the resonance between observation and theory.

Yet natural theology does more than attempt to make intellectual sense of our experience of nature, as if it were limited to the enhancement of a rationalist account of reality. It enables a deepened appreciation of nature at the imaginative and aesthetic level, and also raises questions about how the “good life” can be undertaken within its bounds – matters to which we may now turn.

Beyond Sense-Making: The Good, the True, and the Beautiful

One of the weaknesses of approaches to natural theology to emerge from the Enlightenment is that they saw their task almost exclusively in terms of an enterprise of sense-making, having been obliged to operate within a rationalist straightjacket as a result of the intellectual agendas of the movement. There have, of course, been important challenges to this kind of aesthetic and imaginative deficit, most notably from within the Romantic movement, with its emphasis on the importance of feeling and imagination in any engagement with nature.43 More recently, the waning of modernity has provided a congenial context for the liberation of natural theology, so that its deep intrinsic appeal to the human imagination may be realized. Natural theology is to be understood to include the totality of the human engagement with the natural world, embracing the human quest for truth, beauty, and goodness.

We invoke the so-called “Platonic triad” of truth, beauty, and goodness as a heuristic framework for natural theology. When properly understood, a renewed natural theology represents a distinctively Christian way of beholding, envisaging, and above all appreciating the natural order, capable of sustaining a broader engagement with the fundamental themes of human culture in general. While never losing sight of its moorings within the Christian theological tradition, natural theology can both inform and transform the human search for the transcendent, and provide a framework for understanding and advancing the age-old human quest for the good, the true, and the beautiful.

There is no doubt that, in the past, Christian theology was deeply involved in reflection on the good, the true, and the beautiful. By offering a richly textured account of the world, theology was able to inform and enrich the cultural context of earlier ages through the perception of the capacity of truth to illuminate both goodness and beauty.44 Those connections – evident in the classic medieval notion of “a feeling for intelligible beauty” – have become strained, occasionally to the point of near-rupture, partly through the rise of the Enlightenment, though more particularly through certain trends within Protestantism that were unsympathetic to such broader cultural concerns. The approach to natural theology that we propose encourages the process of reconnection, offering new possibilities to theology within today’s cultural dialogues.

An additional contemporary factor which acts as a stimulus for renewing and reconceptualizing natural theology must be noted. In the last few decades, the dialogue between the natural sciences and Christian theology has accelerated, marking the end of the widespread, yet historically implausible, notion of the permanent warfare of science and theology.45 This increasingly sophisticated and confident dialogue has given a new importance to natural theology as a potential conceptual meeting place for Christian theology and the natural sciences. Where some see boundaries as barriers, we see them as places of dialogue and exploration. Might the renewal of a Christian natural theology establish reliable and productive intellectual foundations for an enriched and deepened engagement between the natural sciences and Christian faith? If the approach presented in this book has merit, this would certainly seem to be the case.

Furthermore, the approach advocated in this book affirms that the empirical is a legitimate means of discovering and encountering the divine. The quest for truth through reflection on nature is to be recognized as an appropriate pathway towards encountering God. Though important questions remain about how it is to be interpreted, the approach to natural theology that we set out in this work affirms both the importance and the validity of an empirical engagement with nature.

Natural theology is thus too important a notion to be left to theologians, of whatever description. The debate over whether there is indeed a navigable channel between the natural and the transcendent, however these may be defined, capable of bearing traffic in both directions, reaches far beyond the boundaries of any single discipline. It is a matter that must involve theologians, philosophers, mathematicians, physicists, biologists, psychologists, artists, and the literary community. This volume cannot hope to provide an Arthurian round table for such a definitive discussion to take place; it can, at least, begin to map out its possible directions, and stimulate its development.

1 The Hebrew term in Psalm 19: 1 here translated as “tell” can bear such meanings as “declare,” “set forth,” and “enumerate.” See further James Barr, “Do We Perceive the Speech of the Heavens? A Question in Psalm 19,” in Jack C. Knight and Lawrence A. Sinclair (eds), The Psalms and Other Studies on the Old Testament, pp. 11–17, Nashotah, WI: Nashotah House Seminary, 1990. Some medieval Christian writers interpreted this psalm allegorically, holding that Paul’s citation of the psalm in Romans 10: 18 implied that the whole psalm was a prophecy of the apostolic preaching under the allegory or image of the created heavens. This view was rejected by Martin Bucer, who regarded this as exegetically implausible: see R. Gerald Hobbs, “How Firm a Foundation: Martin Bucer’s Historical Exegesis of the Psalms,” Church History 53 (1984): 477–91.

2 Throughout this work, we shall assume – without presenting a detailed defense of – a realist worldview. For a defense of this assumption, see Alister E. McGrath, A Scientific Theology: 2 – Reality, London: T&T Clark, 2002, pp. 121–313.

3 The existence of such a transcendent reality is not universally accepted: see, for example, the position set out by Bertrand Russell, “On Denoting,” Mind 14 (1905): 479–93.

4 See especially Jaroslav Pelikan, Christianity and Classical Culture: The Meta-morphosis of Natural Theology in the Christian Encounter with Hellenism, New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1993.

5 Christoph Kock, Natürliche Theologie: Ein evangelischer Streitbegriff, Neukirchen-Vluyn: Neukirchener, 2001, pp. 392–5. Before any reconstruction of the discipline is possible, he suggests, there is a need to bring about “die Enthäretisierung natürlicher Theologie” (p. 392), a somewhat clumsy and artificial phrase which is probably best paraphrased as “the removal of the stigma of heresy from natural theology.”

6 This point was stressed by Stanley Hauerwas in his recent Gifford Lectures: Stanley Hauerwas, With the Grain of the Universe: The Church’s Witness and NaturalTheology, London: SCM Press, 2002, pp. 15–16: “Natural theology divorced from a full [Christian] doctrine of God cannot help but distort the character of God and, accordingly, of the world in which we find ourselves... I must maintain that the God who moves the sun and the stars is the same God who was incarnate in Jesus of Nazareth” (emphasis added).

7 This is about more than cognitive or intellectual change. Thus John Chrysostom argues (in Homilies on Romans, 20) that Paul’s meaning is not that Christians ought to see the world in a new manner, but that their transformation by grace leads to their seeing the world in such a manner. See the excellent analysis in Demetrios Trakatellis, “Being Transformed: Chrysostom’s Exegesis of the Epistle to the Romans,” Greek Orthodox Theological Review 36 (1991): 211–29.

8 See Gordon J. Hamilton, “Augustine’s Methods of Biblical Interpretation,” in H. A. Meynell (ed.), Grace, Politics and Desire: Essays on Augustine, pp. 103–19, Calgary, AB: University of Calgary Press, 1990; John Barton, “The Messiah in Old Testament Theology,” in John Day (ed.), King and Messiah in Israel and the AncientNear East, pp. 365–79, Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press, 1998, especially pp. 371–2.

9 John 1: 14–18; Colossians 1: 15–19; Hebrews 1: 1–8. There are important parallels here with the Renaissance quest for a “natural language,” itself grounded in the natural order, capable of representing “that which is” rather than merely “that which is said.” See Allison Coudert, “Some Theories of a Natural Language from the Renaissance to the Seventeenth Century,” in Albert Heinekamp and Dieter Mettler (eds), Magia Naturalis und die Entstehung der modernen Naturwissenschaften, pp. 56–118, Wiesbaden: Steiner, 1978.

10 See Barr’s comments on the scope of biblical conceptions of natural theology: James Barr, Biblical Faith and Natural Theology, Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1993, p. 138.

11 William P. Alston, Perceiving God: The Epistemology of Religious Experience, Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1991, p. 289.

12 For an introduction, see Alister E. McGrath, “Towards the Restatement and Renewal of a Natural Theology: A Dialogue with the Classic English Tradition,” in Alister E. McGrath (ed.), The Order of Things: Explorations in Scientific Theology, pp. 63–96, Oxford: Blackwell, 2006.

13 There is a large literature, represented by works such as Charles E. Raven, Natural Religion and Christian Theology, 2 vols, Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1953; Peter A. Byrne, Natural Religion and the Nature of Religion: The Legacy of Deism, London: Routledge, 1989; Nicholas Roe, The Politics of Nature:Wordsworth and Some Contemporaries, New York: St. Martins Press, 1992; David T. Morgan, “Benjamin Franklin: Champion of Generic Religion,” Historian 62 (2000): 723–9.

14 See the points made by Richard S. Westfall, “The Scientific Revolution of the Seventeenth Century: A New World View,” in John Torrance (ed.), The Concept of Nature, pp. 63–93, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1992.

15 The celebrated “Boyle Lectures,” delivered over the period 1692–1732, are an excellent example of this approach. For Boyle’s own views on natural theology, see Jan W. Wojcik, Robert Boyle and the Limits of Reason, Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1997. Note also the older study of Harold Fisch, “The Scientist as Priest: A Note on Robert Boyle’s Natural Theology,” Isis 44 (1953): 252–65. These difficulties were initially hermeneutical, relating to problems in interpreting the text; as time progressed, the rise of critical historical and textual studies raised further concerns about the public defensibility of the Christian revelation. For an excellent study, see Henning Graf Reventloh, The Authority of the Bible and the Rise of theModern World, London: SCM Press, 1984.

16 See the analysis in James Schmidt, “What Enlightenment Project?” PoliticalTheory 28 (2000): 734–57.

17 For a detailed analysis of this point, see Alister E. McGrath, A Scientific Theology: 1 – Nature, London: T&T Clark, 2001, pp. 81–133.

18 See Neil Evernden, The Social Creation of Nature, Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1992; Kate Soper, What is Nature? Culture, Politics and the Non-Human, Oxford: Blackwell, 1995.

19 For these categories, I draw on Michael E. Soulé, “The Social Siege of Nature,” in Michael E. Soulé and Gary Lease (eds), Reinventing Nature: Responses to Postmodern Deconstruction, pp. 137–70, Washington, DC: Island Press, 1995. This work includes excellent comments on the postmodern deconstruction of nature and its implications, not least for ecological concerns.

20 For some fascinating illustrations of this point, see the myriad of competing concepts explored in Hans Bak and Walter W. Holbling, “Nature’s Nation” Revisited:American Concepts of Nature from Wonder to Ecological Crisis, Amsterdam: VU Press, 2003.

21 Barr, Biblical Faith and Natural Theology, p. 1.

22 The notion has been explored in other manners, such as Philip Hefner’s notion of humanity as the “created co-creator”: Philip J. Hefner, The Human Factor: Evolution, Culture, and Religion, Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 1993; Gregory R. Peterson, “The Created Co-Creator: What It Is and Is Not,” Zygon 39 (2004): 827–40. The idea can also be developed in a more literary manner, as in J. R. R. Tolkien’s notion of the “subcreator,” which views the artist in this view as an active participant in the creative process. Though artists may refract the light of truth that shines from the creator, they are nevertheless to be regarded as agents of that act of creation. See further Verlyn Flieger, Splintered Light: Logos and Language in Tolkien’s World, rev. edn, Kent, OH: Kent State University, 2002, pp. 49–56. Hefner’s notion of the “created co-creator” can, of course, also be developed in this direction: see Vitor Westhelle, “The Poet, the Practitioner, and the Beholder: Thoughts on the Created Co-Creator,” Zygon 39 (2004): 747–54.

23 This point was implicit in the famous debate between Karl Barth and Emil Brunner in 1934 over the validity and character of natural theology, to which we shall return later in this work: see pp. 158–64.

24 For the issues, see Ian Hacking, The Social Construction of What? Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1999.

25 Leszek Kolakowski, “Concern about God in an Apparently Godless Age,” in My Correct Views on Everything, ed. Zbigniew Janowski, pp. 173–83, South Bend, IN: St. Augustine’s Press, 2005; quote at p. 183. For a more rigorous exploration of this theme, see Charles Taylor, A Secular Age, Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press, 2007.

26 Gilbert Burnet (ed.), The Boyle Lectures (1692–1732): A Defence of Naturaland Revealed Religion, Being an Abridgement of the Sermons Preached at the Lectures Founded by Robert Boyle, 4 vols, Bristol: Thoemmes Press, 2000.

27 Andrew Pyle, “Introduction,” in The Boyle Lectures (1692–1732), vol. 1, pp. vii–liii.

28 For example, some of the most influential lecturers were Arians: Maurice Wiles, Archetypal Heresy: Arianism Through the Ages, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1996, pp. 62–134. For a more general exploration of this point, see the important collection of studies in John Brooke and Ian McLean (eds), Heterodoxy in EarlyModern Science and Religion, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006.

29 Thomas F. Torrance, Theology in Reconciliation: Essays Towards Evangelicaland Catholic Unity in East and West, London: Chapman, 1975, pp. 27–8, 267–8.

30 This thesis underlies the important work by Philip Yancey, Rumors of AnotherWorld: What on Earth Are We Missing? Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 2003.

31 H. E. W. Turner, The Patristic Doctrine of Redemption: A Study of the Development of Doctrine During the First Five Centuries, London: Mowbray, 1952.

32 John of Damascus, Contra imaginum calumniatores, I, 16, in Patristische Texteund Studien, vol. 17, ed. P. Bonifatius Kotter OSB, Berlin/New York: de Gruyter, 1979, pp. 89–92.

33 William P. Alston, Perceiving God: The Epistemology of Religious Experience, Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1991, p. 289.

34 For the impact of this work on nineteenth-century British intellectual culture, including Charles Darwin, see Aileen Fyfe, “The Reception of William Paley’s NaturalTheology in the University of Cambridge,” British Journal for the History of Science 30 (1997): 321–35. For the problems of Paley’s approach, see Neal C. Gillespie, “Divine Design and the Industrial Revolution: William Paley’s Abortive Reform of Natural Theology,” Isis 81 (1990): 214–29.

35 John Henry Newman, letter to William Robert Brownlow, April 13, 1870; in Charles Stephen Dessain and Thomas Gornall (eds), The Letters and Diaries of JohnHenry Newman, 31 vols, Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1963–2006, vol. 25, p. 97. For comment, see Noel Keith Roberts, “Newman on the Argument from Design,” New Blackfriars 88 (2007): 56–66.

36 We shall explore the critical idea of the “open secret” in greater detail in chapter 6. The image of the “open secret” is also found in Lesslie Newbigin’s classic account of Christian mission as the declaration of an “open secret,” which is “open” in that it is preached to all nations, yet “secret” in that it is manifest only to the eyes of faith: Lesslie Newbigin, The Open Secret: Sketches for a Missionary Theology, London: SPCK, 1978. For evaluations, see K. P. Aleaz, “The Gospel According to Lesslie Newbigin: An Evaluation,” Asia Journal of Theology 13 (1999): 172–200; Wilbert R. Shenk, “Lesslie Newbigin’s Contribution to Mission Theology,” International Bulletin of Missionary Research 24/2 (2000): 59–64.

37 C. S. Lewis, “Is Theology Poetry?,” in Essay Collection and Other ShortPieces, pp. 10–21, London: HarperCollins, 2000; quote at p. 21.

38 For possible criteria for the “best explanation,” see Peter Lipton, Inference tothe Best Explanation, 2nd edn, London: Routledge, 2004.

39 John C. Polkinghorne, “Physics and Metaphysics in a Trinitarian Perspective,” Theology and Science 1 (2003): 33–49. The points are developed in greater detail in his Science and the Trinity: The Christian Encounter with Reality, New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2004. For more detailed reflections on the congruence of the Christian worldview with the phenomenon of “fine tuning,” see Robin Collins, “A Scientific Argument for the Existence of God: The Fine-Tuning Design Argument,” in Michael J. Murray (ed.), Reason for the Hope Within, pp. 47–75, Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 1999.

40 Richard Dawkins, River out of Eden: A Darwinian View of Life, London: Phoenix, 1995, p. 133.

41 Both these ideas are, of course, highly problematic – consider, for example, Wittgenstein’s insistence that true logical propositions are little more than tautologies, or Pierre Duhem’s rebuttal of the notion of a “crucial experiment.” See Yuri Balashov, “Duhem, Quine, and the Multiplicity of Scientific Tests,” Philosophy of Science 61 (1994): 608–28; Leo K. C. Cheung, “Showing, Analysis and the Truth-Functionality of Logical Necessity in Wittgenstein’s Tractatus,” Synthese 139 (2004): 81–105.

42 For the issue, see Larry Laudan and Jarrett Leplin, “Empirical Equivalence and Underdetermination,” Journal of Philosophy 88 (1991): 449–72.

43 Richard Eldridge, “Kant, Hölderlin, and the Experience of Longing,” in ThePersistence of Romanticism: Essays in Philosophy and Literature, pp. 31–51, Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2001.

44 See, for example, the important study of Umberto Eco, Art and Beauty in theMiddle Ages, New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1986.

45 On which see Frank Miller Turner, “The Victorian Conflict between Science and Religion: A Professional Dimension,” Isis 69 (1978): 356–76; David C. Lindberg and Ronald L. Numbers, “Beyond War and Peace: A Reappraisal of the Encounter between Christianity and Science,” Church History 55 (1984): 338–54; Colin A. Russell, “The Conflict Metaphor and its Social Origins,” Science and Christian Faith 1 (1989): 3–26.

PART I

The Human Quest for the Transcendent: The Context of Natural Theology

CHAPTER 2

The Persistence of the Transcendent

In spite of everything, we keep on talking about God. Even in seemingly godless ages, God lingers as a tantalizing presence, incapable of eradication by the most vicious of ideologies or technological mechanisms. As Leszek Kolakowski, the distinguished Polish philosopher and historian of Marxism, once commented, “God’s unforgettableness means that He is present even in rejection.”1

Kolakowski’s point is well taken. Despite a formidable array of attempts to reduce, deconstruct, recategorize, or simply evade the notion of the transcendent,2 it remains central to cultural and philosophical reflection.3 Indeed, the history of ideas suggests that the assertion of the hegemony of materialist approaches to reality invariably creates a backlash, generating a new interest in the domain of the transcendent.4 The quest for the transcendent is so deeply embedded in the history of human thought that it needs more to be illustrated, rather than defended.5

Derrida’s approach is thus by far the most carefully consistent, sophisticated and intricate of all post-subject outlooks. Yet even he cannot in the end resist inserting a ‘feel of meaning’ – that is, the feel of aboutness, or of intentional reference (and as such a feel of purpose, obligation, responsibility) – into his post-structuralist enterprise in order to keep its purity from degenerating into mere bleakness.

Recent work in the cognitive science of religion has suggested that transcendent ideas or religious beliefs are “minimally counterintuitive concepts,” which resonate with and are supported by “completely normal mental tools working in common natural and social contexts.”6 If this is so, it follows that religion and an interest in the transcendent will remain an integral part of human culture, in that they represent a “natural” outcome of human cognitive processes – in contrast with science, a correspondingly “unnatural” outcome, which requires constant defense and maintenance if it is to survive. This insight was anticipated by Nietzsche, who pointed out that the metaphysical pressure to discover “God” never departs, but lingers within human culture and experience:

How strong the metaphysical need is, and how hard nature makes it to bid it a final farewell can be seen from the fact that even when the free spirit has divested himself of everything metaphysical, the highest effects of art can easily set the metaphysical strings, which have long been silent or indeed snapped apart, vibrating in sympathy... He feels a profound stab in the heart and sighs for the man who will lead him back to his lost love, whether she be called religion or metaphysics.7

So what is “transcendence”? How may it be defined, or at least described? The term is used in at least three senses in recent literature.

1 The idea of self-transcendence. The term can be used to refer to mastering natural limitations through the use of technology or mental and physical strategies. For example, Thomas Nagel argues that transcendence designates an act of empathetic imagination which enables us to stand in another’s position, and see things from an alternative standpoint.8 If an objective view is to be achieved, Nagel suggests, human observers must be able to purge themselves of their idiosyncratic perceptions, often determined by their individual viewpoints, and rise above themselves to grasp a greater vision of reality. It is clear that transcendence here bears a somewhat reduced meaning, along the lines of: a capacity to transcend my personal viewpoints, thus allowing me to see things from a broader perspective.

2 A realm beyond ordinary experience. In its traditional sense, the word “transcendence” has ontological significance, referring to something that is held to exist beyond the realm of the mundane, yet which may be encountered or experienced, even if only to a limited extent, within the ordinary world. This way of thinking about transcendence postulates a frontier beyond which human knowledge cannot penetrate, so that there is always a “beyond” that remains elusive. The noted physicist André Mercier (1913-99) expressed this basic idea as follows:

Somehow reality always manages to resist man’s final grasping. This resistance leads us to believe that reality in one sense always remains beyond the point of contact between itself and man. There seems to be a permanent “something” in reality which lies outside man’s finite domination. Of this “something,” we have only an idea.9

3 Experiences which are interpreted to relate to a transcendent reality. This third sense of the term is used psychologically to refer to experiences which are interpreted in transcendent terms. It is often used to describe a tantalizingly transient sensation that the individual has somehow entered the extraordinary – that the mundane has given way to something beyond it. William Wordsworth tried to capture this idea in the phrase “spots of time” – rare yet precious moments of profound feeling and imaginative strength, in which individuals grasp something of ultimate significance within their inner being.10 It proves virtually impossible to express this experiential aspect of the transcendent in everyday language. Hans-Georg Gadamer suggested that transcendence is about “a kind of experience, for which a mere playing around with ideas cannot be substituted.” It is, he suggested, something irreducible that is experienced as a “presence” (Gegenwärtigkeit) that does not permit a heightened precision of definition.11

Although this book engages with all three senses of “transcendence” as set out above, our particular concern in this book is with this third understanding of the idea. We shall argue throughout Part I that transcendence continues to be a meaningful concept in contemporary culture. It is a notion that is found in religious and secular literature alike, reflecting what seems to be a common human preoccupation.12