Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Salt

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Serie: Modern Dreams

- Sprache: Englisch

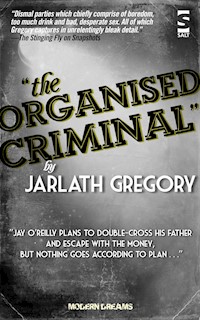

Jay O'Reilly returns home for a family funeral after an absence of three years. His father, the most successful smuggler in Northern Ireland, asks for his help in return for one hundred grand. Jay is tempted by the money, and the chance to help his cousin Scarlett escape her abusive relationship. He turns to his friend Martin, a gay half-gypsy, for advice. But nothing goes according to plan...

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 111

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2014

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

THE ORGANISED CRIMINAL

Jay O’Reilly returns home for a family funeral after an absence of three years. His father, the most successful smuggler in Northern Ireland, asks for his help in return for one hundred grand. Jay is tempted by the money, and the chance to help his cousin Scarlett escape her abusive relationship. He turns to his friend Martin, a gay half-gypsy, for advice. But nothing goes according to plan…

“The Organised Criminal is a masterly novella of male friendship, family betrayal and economic corruption. By turns brutal, beautiful and funny, it’s an astute exploration of a Northern Ireland rarely seen in fiction.” JAMIE O’NEILL, author of At Swim, Two Boys

“Jarlath Gregory’s The Organised Criminal has themes which are familiar - family, betrayal, love and death - but the setting and the characterisations and the telling of the tale make this a distinctive and fresh book, one that can read like a thriller but linger like something much more dangerous.” KEITH RIDGWAY, author of Hawthorn & Child

“The Organised Criminal is a hugely enjoyable read. A book brimming with rage and indignation, hewn from the very darkest of materials but always tempered with well judged humour and sharply observed detail. It is a novel of ideas as well as a cleverly drawn crime thriller. It demands to be read.” MARK O’HALLORAN, writer and director of Adam & Paul

JARLATH GREGORY is the author of Snapshots (2001) and G.A.A.Y One Hundred Ways to Love a Beautiful Loser (2005). He is a graduate of Trinity College Dublin.

Also available from Modern Dreams

Devil On Your Back by Denny Brown

Sky Hooks by Neil Campbell

Songs of the Maniacs by Mickey J Corrigan

The Pharmacist by Justin David

Precious Metal by Michelle Flatley

Albion by Jon Gale

The Organised Criminal by Jarlath Gregory

Riot by Jones Jones

Marg by Jones Jones

Desh by Kim Kellas

Carrion Men by V.C. Linde

Choice! by Rachel Medhurst

Stuff by Stefan Mohamed

The Blame by Michael Nolan

Published by Salt Publishing Ltd

12 Norwich Road, Cromer, Norfolk NR27 0AX

All rights reserved

Copyright © Jarlath Gregory,2014

The right ofJarlath Gregoryto be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with Section 77 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

This book is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to provisions of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part may take place without the written permission of Salt Publishing.

Salt Publishing 2014

Created by Salt Publishing Ltd

This book is sold subject to the conditions that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out,or otherwise circulated without the publisher’s prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

ISBN 978-1-78463-016-4 electronic

01. Wake

Duncan was being waked in his mother’s semi-detached home. Dozens of cars were parked in and around the labyrinthine innards of the concrete estate. Kids with plastic toys played on the kerbs, oblivious to death and its aftermath. I flipped down my sunshade and looked in the mirror. My eyes were anxious. My palms were sweaty.

Weddings, funerals, what was the difference?

I prepared myself for duty.

My mum calmly straightened her necklace, applied another layer of lipstick, and patted her hair.

“Look lively.”

I flicked my smouldering cigarette butt into a ditch. It had once been a laneway between neighbouring estates where kids from either side of the divide had come to wage mock wars, but it had since been cleaned up, landscaped, and fenced off. A peeling piece of graffiti spelled I.R.A. in bottle green, off white, and burnt orange.

Dolores walked briskly ahead. The first person we met at the door was Duncan’s brother Seamus. We’d never got on.

“Seamus, I’m so, so sorry, where’s your poor mother?”

Dolores sailed onwards, leaving me to shake hands awkwardly with my cousin.

“Jay, long time no see. Get yourself a drink, man. I’ll catch up with you later.”

The usual herd of extended family milled in and out of rooms. I caught glimpses of familiar faces, those faces you only ever see at weddings or funerals. There’d be time enough for conversation later. I went upstairs to pay my respects.

All the blinds in the house were drawn. Plates of sandwiches and tea were doing the rounds, attached to various capable women, the sort of women who always seemed to be at wakes. I could smell the whiff of booze from downstairs.

I braced myself to walk through the door to Duncan’s old bedroom.

The room was crowded with mourners, interspersed with the tricks of the Catholic trade – candles, holy water, a priest. Weird, that there was still a market for all that holy tat. The murmurs died for a second as I entered the room, then picked up again, slightly louder than before. Dozens of pairs of eyes took me in while pretending not to. I stared at the coffin.

It lay lengthways across the room, side on as you entered.

It was mahogany with brass fittings.

It was open.

While silk ruffles cushioned the dead, sewn shut, made up face of my cousin. Duncan looked both bloated and drained, if that was possible. It made sense when you realised he’d been bloated by booze before death, and drained of blood by the embalmer afterwards.

A wad of padding had come loose from one nostril. Someone ought to fix it, in case Duncan’s face leaked, in case that became the last image I’d ever be able to conjure up of my cousin again – the spongy face, leaking brain sewage through its nose, down its drawn lips, dripping from the chin. But I couldn’t bring myself to reach across and touch the body. Like everyone else, I pretended the dislodged nose plug wasn’t there.

I stepped forward.

Several bodies melted away in deference to a relative of the deceased.

I forced myself to look down upon the face of Duncan Goodman for the last time. I clasped my hands together in what I knew the room would take for silent prayer, although no prayers came to mind, only a contemplation of the dead.

My earliest memory of my cousin was just an image, sun-bloomed, hazy, and faded round the edges like an overexposed photograph from the Nineties – which it was, in a way, except it had been recorded in my brain, as a young child growing dimly aware of the strange world I was part of.

We must have been six or seven. Duncan stood chest high in overgrown grass, grinning with gaps in his teeth, blond curls made dark by the sun dancing over his shoulder. A home-made jumper, knitted by Aunty Kate. Freckles. If I tried too hard to focus on the picture, my cousin’s face would morph into an older version of itself, the teeth crooked and stained, the hair sparse and colourless, the cheeks and nose mottled with alcohol, the eyes smashed and gluey like broken eggs.

The room returned. Light filtered through gauzy curtains. The wreaths around the coffin were scentless and sombre. I said goodbye to Duncan and tried to focus on the normal things. The chink of china teacups borrowed from the football club. The rough fabric of the black chairs brought by the funeral home. Shuffling shoes, clasped hands, the solid chill of a house with the heat turned off, both out of respect for the dead, and the practical necessity of keeping the body cool.

All part of the great Northern Irish theatrical tradition of the family wake.

At first, I didn’t hear the voice at my ear.

“Jay? Jay? Cup of tea, Jay?”

My cousin Scarlett thrust a laden tea tray under my nose.

“Have a cup of tea, you’ll feel much better.”

“Thanks.”

“I’ve put a drop of whiskey in it, just for you,” she whispered.

I accepted the concoction gratefully. Scarlett’s thin wrist bones made the china look clumsy. She was wearing a Claddagh ring, turned inwards to show she was engaged. I hadn’t seen one of those in years.

I looked up into her face, surprised.

She smiled back brightly and widely.

“Come outside. We could both use some fresh air.”

Everyone gave way to the tea tray. Scarlett nodded at two smokers in the back yard and perched on top of the coal bunker, plonking the tray down on its sloping lid at a disarming angle. We sat in silence. I lit a cigarette and blew smoke rings at the sky. A crackling spool of film played across my mind, a film of the last time I’d seen our cousin alive.

Duncan had been living in a dingy council flat, the kind he used to take the piss out of people for being from. Newry had improved since we’d been to school – it now had coffee shops as well as shopping centres, stellar hotels as well as self-service petrol stations, successful drug-dealers as well as rat-arsed pubs – but the old slums still slumbered amid the glass and chrome complexes, sleeping alongside the vroom and tinkle of the coin-operated car-parks, ignored by the twinkling clamour of the bells of the Cathedral, which always conjured up images of confetti and doves fluttering through the air, even as smog slipped through your hair. If you squinted just right, the haze of a weak summer sunlight filtering through pollution might make the rooftops, windows and traffic shimmer like any British high street, with international brand names punctuating the depressing local muddle of the markets, the undeveloped outskirts, the sink estates. Up close and personal, sectarian graffiti dripped off peeling walls. Mums pushed prams past half-cracked beggars, greeting them by name with weary tolerance. Tracksuits were the uniform of the non-working classes. And it was here, in the midst of the squalor and decay, up the inevitably piss-soaked stairway, past the same laundry hanging on the same balcony with the same child crying in the background that I remembered from my daily walk to school three years ago, that my cousin had drank himself to death.

The smokers tossed their cigarette butts to the ground, where they bounced and smouldered like spent bullet shells. The noise of children from the estate rose above the wall. Pale light bled the concrete white. It was nice, sitting there with Scarlett. We were the same age, but I only saw her on Facebook these days.

A fly landed on a slice of cake. Scarlett idly pressed her thumb on top of it, squashing its body into the moist crumb.

“You know what I call this dense fruit and vanilla flavoured sponge?”

“Shock me.”

“Wake cake. You only ever get it at wakes, and no wake is complete without it.”

Scarlett wiped her thumb off on her jeans.

“Let’s go back and see if we can force this slice on Fr Flaherty.”

“Deal.”

Scarlett slid off the coal bunker, put on a smile, and picked up the tray. Her Claddagh ring caught a glint of sunlight.

“I didn’t know you’d got engaged.”

Before she could answer, a banshee wail rose from the scullery. Aunty Kate came wobbling out into the yard, arms outstretched, fresh tears pricking her eyes.

“Jay, you came home, you came home…”

I met her outstretched arms in an awkward embrace, then held her to my chest as she sobbed, while men looked at the floor, and the smile faded from Scarlett’s lips, the tea tray growing heavier in her hands.

Back indoors, I found myself clutching a whiskey. Men, loud and fat, backslapped each other. I poured the shot straight down my throat, and poured myself another. The whiskey stung the back of my eyeballs.

The men were smugglers, or business associates of my dad, if you preferred. Frank O’Reilly had run the family business, namely the lucrative cross-border smuggling industry, for four decades. It was one of those elusive facts of life which everyone believed but nobody could prove, like the existence of dark matter. “They call this Bandit Country,” he would grunt, “but the only bandits round here are wearing British army uniforms.”

I’d always known that you weren’t supposed to talk about it. I brushed my teeth, washed my face, went to school, and didn’t talk about it. I played chase, did my homework, kept my head down, and didn’t talk about it. I kicked a ball around, shared a cigarette, kissed a girl if I got the chance, but still, I never, ever, spoke about my dad’s business.

“Rule number one,” Frank drummed home, “we don’t talk about it. That’s how we get rich, and stay rich.”

Rich. Yeah, we were rich, but we didn’t brag about it. Instead, we wore it in a certain swagger, in a winter tan and a smattering of Spanish, in never having to explain ourselves, because, just as I never talked about my dad being a smuggler, nobody else did either.

“Son.”

I spun around.

My father stood in the middle of the room, like a bullock in a black suit.

“Come with me, Jay. I need to have a word.”

The room fell silent. This was the moment that everyone had been waiting for. The whiskey burned a hole in my belly. I did as I was told. I followed my father out of the room, through the crowd, and into the estate. A child was pouring a can of beer into the gutter, where cigarette butts floated like dead goldfish in a pissy pond.

02. Money