Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Atlantic Books

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

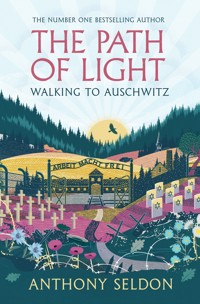

Praise for The Path of Peace: 'A formidable achievement' Rory Stewart 'Thoughtful [and] heartfelt' Observer 'Profound [and] compelling' Spectator 'A noble endeavour' New Statesman In 2021, Anthony Seldon, inspired by a fallen First World War soldier who dreamed of a 'Via Sacra' to commemorate the war dead and stand as a marker for the triumph of peace, set out on a 1,000km walk tracing the historic route of the Western Front. He went on to recount that story in the widely acclaimed The Path of Peace. But there wasn't to be lasting peace, with the continent falling into an even more horrific war two decades later. In The Path of Light, Seldon sets out to walk a new 1,300 km route from the same starting point at Kilometre Zero to Auschwitz, discovering in the towns and villages through which he walks stories of women and men who bravely protected the vulnerable and stood up to evil in the face of unimaginable brutality during the Second World War. As he ruminates on these 'figures of light', whose uplifting stories he encounters along his path, a pattern begins to emerge about how we can draw on their lives to build a better and more peaceful world, never more needed than now, with the ominous and increasing drumbeat of belligerence globally that month by month is the constant backdrop of his walk between 2023 and 2025. It proved a harder book to write than The Path of Peace. But it was a project he knew he had to complete, whatever the cost.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 569

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2025

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Also by Anthony Seldon

Churchill’s Indian Summer: The Conservative Government 1951–55

By Word of Mouth: Elite Oral History

Ruling Performance: Governments since 1945 (ed. with Peter Hennessy)

Political Parties Since 1945 (ed.)

The Thatcher Effect (ed. with Dennis Kavanagh)

Politics UK (joint author)

Conservative Century (ed. with Stuart Ball)

The Major Effect (ed. with Dennis Kavanagh)

The Heath Government 1970–1974 (ed. with Stuart Ball)

The Contemporary History Handbook (ed. with Brian Brivati et al.)

The Ideas That Shaped Post-War Britain (ed. with David Marquand)

How Tory Governments Fall (ed.)

Major: A Political Life

10 Downing Street: An Illustrated History

The Powers Behind the Prime Minister (with Dennis Kavanagh)

Britain under Thatcher (with Daniel Collings)

The Foreign Office: An Illustrated History

A New Conservative Century (with Peter Snowdon)

The Blair Effect 1997–2001 (ed.)

Public and Private Education: The Divide Must End

Partnership not Paternalism

Brave New City: Brighton & Hove, Past, Present, Future

The Conservative Party: An Illustrated History (with Peter Snowdon)

New Labour, Old Labour: The Wilson and Callaghan Governments, 1974–79

Blair

The Blair Effect 2001–5 (ed. with Dennis Kavanagh)

Recovering Power: The Conservatives in Opposition since 1867 (ed. with Stuart Ball)

Blair Unbound (with Peter Snowdon and Daniel Collings)

Blair’s Britain 1997–2007 (ed.)

Trust: How We Lost it and How to Get It Back

An End to Factory Schools

Why Schools, Why Universities?

Brown at 10 (with Guy Lodge)

Public Schools and the Great War (with David Walsh)

Schools United

The Architecture of Diplomacy (with Daniel Collings)

Beyond Happiness: The Trap of Happiness and How to Find Deeper Meaning and Joy

The Coalition Effect, 2010–2015 (ed. with Mike Finn)

Cameron at 10 (with Peter Snowdon)

Teaching and Learning at British Universities

The Cabinet Office 1916–2016 – The Birth of Modern British Government (with Jonathan Meakin)

The Positive and Mindful University (with Alan Martin)

The Fourth Education Revolution (with Oladimeji Abidoye)

May at 10 (with Raymond Newell)

Public Schools and the Second World War (with David Walsh)

Fourth Education Revolution Reconsidered (with Oladimeji Abidoye and Timothy Metcalf )

The Impossible Office? The History of the British Prime Minister (with Jonathan Meakin and Illias Thoms)

The Path of Peace: Walking the Western Front Way

Johnson at 10 (with Raymond Newell)

Truss at 10 (with Jonathan Meakin)

First published in hardback in Great Britain in 2025 by Atlantic Books, an imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd.

Copyright © Anthony Seldon, 2025

The moral right of Anthony Seldon to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

No part of this book may be used in any manner in the learning, training or development of generative artificial intelligence technologies (including but not limited to machine learning models and large language models (LLMs)), whether by data scraping, data mining or use in any way to create or form a part of data sets or in any other way.

The picture acknowledgements on p. 357 constitute an extension of this copyright page.

Every effort has been made to trace or contact all copyright holders. The publishers will be pleased to make good any omissions or rectify any mistakes brought to their attention at the earliest opportunity.

Map artwork by Jess Macaulay.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Hardback ISBN: 978 1 80546 410 5

E-book ISBN: 978 1 80546 411 2

Printed in Great Britain

Atlantic Books

An imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd

Ormond House

26–27 Boswell Street

London

WC1N 3JZ

www.atlantic-books.co.uk

Product safety EU representative: Authorised Rep Compliance Ltd., Ground Floor, 71 Lower Baggot Street, Dublin, D02 P593, Ireland. www.arccompliance.com

This book is dedicated to two transcendent figures of light, Dietrich Bonhoeffer (1906–45) and Etty Hillesum (1914–43), both victims of Nazism.

God is light; in him there is no darkness at all.1 John 1:5

Contents

Preface

1 Crossing the Rhine

2 Black Forest, White Rose

3 Swiftly Flows the Danube: Ulm to Donauwörth

4 One Way, Four Paths: From Donauwörth to Nuremberg

5 The Road to Flossenbürg

6 Sudetenland: From Flossenbürg to Prague

7 Prague, Lidice, Terezín

8 Central and East Bohemia: Prague to Pardubice

9 Into Moravia: Pardubice to Ostrava

10 Silesia, Poland, Auschwitz

Epilogue

Illustration Credits

Notes

Acknowledgements

Index

Preface

I MUST WALK TO Auschwitz. I will have failed the biggest challenge of my life if I don’t. Since my mid-teens, the concentration camp has possessed me. I have never understood why. Visiting it, as I had done on five occasions, hadn’t provided answers. Might travelling to it the long way, by foot, confronting my own inner demons as I did so, unlock any light? Step by painful step, I thus decided to walk across Europe till I arrived in south-eastern Poland where Auschwitz and its string of subordinate camps lie just 200 kilometres short of the border with Ukraine.

Auschwitz is the darkest example in history of intentional mass barbarity. The apex of evil and cruelty. Would I be hearing in the villages, towns and cities along my route yet more stories of man’s inhumanity during the Nazi era (1933–45)? In the eighty years since the war ended have we heard enough perhaps about human depravity? Is a rebalancing needed? So I decided instead to unearth stories, if I could, of human goodness, compassion and courage along my trail. I wanted to be uplifted on my way by learning about men and women of honour who at great risk protected those deemed by the Nazis to be ‘others’. I craved not more tales of human darkness, though inevitably and for contrast my story would contain some, but human light. I am going to walk to Auschwitz in search of light. To create indeed a ‘path of light’ across the heart of Europe to uplift others, perhaps even to lighten their darkness. To provide a different narrative to the light of despair of the Auschwitz crematoria whose chimneys belched out burning human embers, illuminating even the darkest night skies between 1941 and 1945.

I had already walked half the distance. Task half done! During the second Covid summer, 2021, I travelled by foot from ‘Kilometre Zero’ where the trenches of the First World War abruptly ended at the Swiss border, to Nieuwpoort on the North Sea where the front line began on the Belgian coast.1 That 1,000-kilometre walk, which took me 1 million steps through soil where 10 million fell, was designed to encourage a permanent path along No Man’s Land that we called the ‘Western Front Way’, conceived originally in a British officer’s letter I had discovered by chance when researching a book on the First World War. The soldier with the rousing vision, one of the most uplifting to emerge from the war, Douglas Gillespie, was killed shortly after writing it down; his letter then lay dormant for a hundred years. I recounted the story of its discovery and the walk in The Path of Peace, published in 2022. One of the themes is that we are all affected today by the trauma of what happened in those four shattering years between 1914 and 1918; though distant, the Great War’s ghosts still linger. This present volume, focused on the Second World War, is a sequel. I would set out on this walk from the exact point, Kilometre Zero, where the first walk started, and where hostilities ceased when the First World War ended.

My intention was to start out in the spring of 2023 and complete the walk before the weather turned, walking day by day east from Kilometre Zero till I arrived some 1,300 kilometres later at Auschwitz. But unlike that first walk, there was no former front line to follow, no line of villages détruits (destroyed villages) nor of vast cemeteries. Instead, I would walk east, on as direct a path as possible. I had a vague idea of my travel: Basel, Freiburg, Ulm, Augsburg, Nuremberg, Flossenbürg, Prague and Kraków, but otherwise I did not know what fate had in store. I wanted to walk along as many rivers as possible, a particular passion, through the four countries: France, Germany, the Czech Republic and Poland. The plan was to finish walking by the end of summer, and have the book written by Christmas 2023.

It was nearly time to depart when on the evening of Sunday 12 February, returning from a walk to prepare for the journey, my phone rang. ‘You don’t know me, but I’m Dr Alastair Wells, chair of governors at Epsom College.’ I’d heard of the tragedy at his school the previous weekend from my children. I had been head of two schools and our three children had been brought up in heads’ houses in the midst of the campuses. Emma Pattison, Epsom’s radiant and brilliant new headmistress, and her seven-year-old daughter had been murdered in the head’s house in the middle of the school, presumably by the husband who then killed himself. I thought I was going to be asked for advice on who might come in to run the school. Instead, he asked me if I could take it on myself. I hadn’t expected that. ‘When?’ I stuttered. ‘Immediately.’ ‘Let me talk to my wife Sarah,’ I replied. My first wife Joanna, the mother of our children, had died six years before from cancer, and I had married Sarah less than a year ago. We were still building our lives together. I felt instinctively I had to do it, ‘running towards the fire’ the image in my head. Sarah is far more practical than I am. She saw quicker that it would turn our lives upside down. But she readily agreed. We both knew in our hearts it was the right thing to do.

I was to be at Epsom for eighteen months until the summer holidays of 2024. Being head of a boarding school is a more than a full-time job. The only way I knew how to do it was to throw myself into the life completely, which meant spending most evenings and weekends at school, doing what I could to bring everyone through the tragedy as positively and cheerfully as possible. Not a day went by when I didn’t think about Emma and her family. I wanted to preserve her memory as best I could. I didn’t even change her study whose redecoration in lily white with lavender curtains had only been completed the week I arrived. I always felt a deep peace in the room: never fear, but a sense of her benign presence. A room of light indeed.

The unexpected job meant that I would have to rethink my strategy for the walk. Very well, I thought. No longer can I do this in one haul as with the Great War walk. I would have to break it up into bite-size chunks, fitting them in around school holidays, book writing and other commitments, all of which had piled up remorselessly. I would try to make a virtue out of necessity, and walk less punishingly than in 2021.

Finding time to juggle running a school with walking proved to be just one of the challenges I would face. I had not grown younger since the first walk and was now on the cusp of my seventieth birthday. Perhaps three score years and ten is meant to be our natural span. Certainly, after a life with barely a day lost through illness, I was to find myself suddenly assaulted by an unexpected health problem, as readers will hear. I would have to learn to take more care of myself this time. I had made so many naive blunders on that first walk which culminated in four separate outpatient visits to hospital. The day after I returned home in late September 2021, I awoke to find I was unable to move more than a few metres. I had pushed myself to the very limits of my endurance, perhaps beyond, and was in a state of physical and mental exhaustion. My body recovered after a few days, but not my feet. Walking for at least six hours a day for thirty-five days with only one short break for my daughter’s wedding had stripped layers of skin off my soles and ankles. I had foolishly assumed that, because I could walk 35 kilometres in one day, I could walk that distance day after day. The stupidity of it. Inflexible boots and rough socks added to my folly, and it meant that towards the end of the walk, every time I put my foot down on the ground, searing pain shot from my soles up both legs. Looking back, I could have done myself serious harm, not least walking with a heavy load by the side of busy roads in the heat of the midday sun or when overtired at the end of the day. I was just a stumble away from potential disaster. This time round, I determined, what my body might lack in youth could be made up for in wisdom. Or so I hoped.

The very distance, 1,300 rather than 1,000 kilometres through four countries with no precise route to follow, posed further challenges. So too would be walking eastwards away from home rather than westwards back towards it, as I consciously did on the first walk. Would having as my destination Auschwitz rather than home prove a psychological block? True, I was looking for light on my way, and choosing to enter the camp on foot rather than being herded there at gunpoint in cattle carriages. I could leave whenever I wanted. But my goal of those infamous gates, with the words ‘Arbeit macht frei’ (‘work sets you free’) above them, was still daunting.

The hope of establishing a permanent trail had proved vital in keeping me going in 2021, especially after the walk became hard, lonely and painful. The widely publicized mission to raise awareness of the Western Front Way and thereby boost the number of travellers meant I dare not fail. But would I be as fired up by the mission of this second walk as I had been by the first? I wasn’t sure. Would I really find telling examples of human bravery and compassion along my route? Thanks to Steven Spielberg’s film Schindler’s List, everyone knew the story of German factory-owner Oskar Schindler, who rescued hundreds of Jewish workers from the crematoria by putting them to work in his plants. But were there others like him, whose stories were untold? Was he really as good a man as has been made out, and could I be sure other figures of light I might encounter were genuine?

The timing of the new book’s publication, in the eightieth anniversary year of the end of the Second World War, would be a spur. I wanted to probe what exactly we would be remembering, now the sacrifice of those who had fought was passing out of living memory. Would the anniversary be anything more than an excuse for celebrating a historic victory and indulging in a pageant of nostalgia and films? It made me all the more eager to find or revive stories that would uplift and inspire the young and old. The sorrow I feared is that the names and deeds of many of the most remarkable heroes will have been erased from human knowledge: the million selfless acts by soldiers caring for others on battlefields, of civilians surviving endless bombing raids or protecting victims, and prisoners sacrificing their food for others in the camps, all lost. But if I could highlight the lives of inspiring heroes might it provide an alternative to the toxic and misogynistic influencers filling the minds of young people? To the nihilism of so much of social media?

The walk was under way at the time of the 7 October 2023 invasion of Israel by Hamas and the brutal war that has followed. Developments in that violent struggle were to form its constant backdrop. The sufferings of the Jews have continued throughout history across Europe. Their victimization down the ages would be a leitmotif of the walk. The Holocaust hastened the establishment of the State of Israel in 1948. I am deeply convinced that Israel has a right to exist behind secure borders. But do the country’s leaders of today have a duty to conduct themselves in a more enlightened way (that word ‘light’ again) than Jews themselves have been treated by others? This would be one of the many difficult moral questions I must confront.

I wanted this book to probe the nature of what we mean by goodness and courage. I studied Philosophy as part of my undergraduate degree. Rather than asking us students to tackle questions of good and evil, right and wrong, justice and injustice, we were fed a diet of dry philosophical texts by Hegel and Nietzsche, with, to me, little real world application. This, I suspected, suited the interest of academic philosophers, but was of less interest to young minds eager to engage with the big questions of life. I wanted my book to explore these questions in the real crucible of war, and ask why so few challenged the brutal regime. Why was the Judaeo-Christian injunction to ‘love your neighbour’ so little followed, not least by ordained ministers? What character and motivation lay behind those who did stand up? How might we react today if we faced the appalling moral dilemmas that Nazism presented? Would we do the ‘right’ thing if it placed our families or communities at risk? Were those who stayed quiet afraid of the consequences of acting, and why did so many believe that the genocide of an entire race of people, namely the Jews, together with Slavs, Roma, homosexuals, the mentally and physically ill and political prisoners, was justified to build a ‘purer’ world?

The walk was going to be a personal pilgrimage too. Might it help me become a kinder person, a better husband and face up to my inner turmoil including the fear of failure and inadequacy that has stalked me all my life? I discuss whether I found any answers to the questions I pose above in the Epilogue.

The book was given added piquancy by the rise of populism and aggressively nationalist leaders. The background noise to this book was, besides the Middle East, the war in Ukraine, the emergence of pro-Russia leaders in Eastern Europe, the election of Donald Trump, the ambitions of President Xi of China, President Putin, and the pivot of the United States away from Europe for the first time so strongly since 1945. Key dates like flagstones paved my way to Auschwitz: 24 February 2022, the Russian invasion of Ukraine; 7 October 2023, Hamas’s attack on Israel; 8 December 2024, the fall of the Assad regime in Syria; 20 January 2025, the second inauguration of President Trump; 20 June 2025, the US attack on Iran’s nuclear facilities, either reducing or enhancing the risk of a Third World War. Each new flagstone was taking us closer to what? And where was the voice of the overlooked men and women everywhere who just wanted peace and friendship, not to go to war at the behest of their leaders? Not for me, leaders who want to separate and divide. I wanted my walk to encourage people to find what they share in common with others, not what divides them. That quest, in a world in which hate and aggressive nationalism are on the rise, would really spur me on.

Finally a confession. I have skin in the game. My father Arthur Seldon was Jewish, the child of Ukrainian immigrants who had fled the pogroms only to perish in East London in the influenza plague at the end of the First World War. My three children would all have been condemned by the Nazis because they had three grandparents who were Jewish. My mother Marjorie Willett was Christian, so in line with Jewish law, I converted to Judaism to marry my first wife Joanna, who was Jewish. I recall Hugo Gryn, the celebrated rabbi telling us about an episode he experienced in the concentration camps in the final winter of the war, 1944–45. During the Jewish festival of Chanukah, the festival of light, it is customary for Jews to light candles. His father lit a wick in a bowl of margarine, only for it to sputter out, because margarine does not burn. Hugo protested and wept at the apparently futile gesture; they needed the food and could not waste it on a candle. His father replied, ‘You and I had to go once for over a week without proper food and another time almost three days without water, but you cannot live for three minutes without hope!’2

That hope of candles burning dimly is a powerful example of light. Light indeed at the end of the path of light.

1

Crossing the Rhine

‘DO YOU THINK YOU can do it?’

‘I’ve done it before.’

‘And look at how difficult you found it! Do you really have to walk all the way?’

‘Of course I do,’ I shoot back.

‘But why? Honestly? It will be so much harder than last time.’

I go quiet. One thousand three hundred kilometres. Route, unknown and perhaps unfindable. Languages I cannot speak. Heroes it may be impossible to find. And time, how will I now find it?

It is the 2023 summer holidays and we are driving across northern France to the Swiss border for the start of the great adventure. Sarah’s questions have touched a raw nerve. At heart, I am not confident I can make it work. Is that why, in contrast to the Western Front walk which I told everyone about who would listen, I have kept this walk virtually a secret? Once I started at Epsom College in February, we moved into rented accommodation halfway between it and Sarah’s school, complicating her life greatly, and now the summer term is over, whoosh, we are off.

We put on The Rest is History podcast, appropriately about my hoped-for destination, Auschwitz. Journalist Jonathan Freedland is discussing his book The Escape Artist about Rudolf Vrba (born Walter Rosenberg) who in April 1944 broke out from the concentration camp and survived, having committed to memory every last detail of the horror that he had witnessed, including the numbers of trains arriving, the origin of the passengers and the fate that befell them, helping himself remember by reciting each morning his accumulating ‘mountain of facts’.1 It gives me an idea.

‘Do you think I could count Vrba as the book’s first “figure of light”?’ I ask Sarah. We talk it over. Technically, my self-imposed ‘rule’ is that I have to discover a connection with a courageous person along the actual route I am walking, otherwise the book will just become a compendium of heroic people in the Second World War from across Europe. Sarah, as a languages teacher, can be disconcertingly precise. But we decide, yes, he qualifies. I have my first figure of light, and I haven’t even started walking yet!

Vrba escaped across southern Poland and into Slovakia, but once in safety found himself caught up in a different battle, to be believed by sceptical authorities who couldn’t or wouldn’t accept the shocking truth he was telling them. He warned that preparations were being made for the mass murder of Hungary’s still untouched Jewish population and that they must be alerted.2 The Slovakian Jewish Council questioned him for six hours, and he had felt that he had won them round, but was bitterly frustrated when they did not apprise the Jewish Council in occupied Hungary. He and his fellow escaper, Alfred Wetzler, met repeated brick walls even after they subsequently wrote their famous Vrba-Wetzler Report, published in November 1944 by the US government. What clearer example of courage and selflessness could there be to inspire me at the very outset of my path of light?3

We break the journey at 8 p.m. at Reims where, for nostalgia, we book into the same hotel, the Campanile on the Aisne-Marne canal, where I’d stayed on the Western Front walk two years before. Enticing champagne bottles are everywhere on offer but we opt for a quiet dinner in the hotel and an early night. The next day, we drive down to Kilometre Zero, the place where the insanity of the Western Front collided with neutral Switzerland’s border, covering the sixteen days I spent walking two years before, I noted wryly, in under five hours.

Kilometre Zero, two years on.

By 3 p.m. we are back at the famous if little-visited landmark on the Swiss border, looking remarkably unchanged over the two years. Sarah photographs me with my foot on the same pillbox as in August 2021. This time the sun is shining and we joke together; I note how much more relaxed I am now even if I miss the confident energy of that first trip. Kilometre Zero is as deserted and silent as it would have been on Armistice Day, 11 November 1918. By then, the French and German soldiers here had no appetite left to kill each other. The serious fighting since March 1918 had been going on north-west of the Vosges mountains, starting with the great German Spring Offensive that broke the trench stalemate, followed by an unstoppable Allied counterattack in Champagne, Picardy, Artois and Flanders that ended in Allied victory.

The German army commanders had in fact forgotten Alsace and much of the area had succumbed to anarchy, with a ‘Republic of Alsace Lorraine’ declared to the raising of red flags in Strasbourg on 8 November. News of the Armistice on 11 November received a mixed response from the German soldiers who were given stern orders to evacuate Alsace altogether within fifteen days.4 Some were eager to get back to the Fatherland to fight for or against Communist uprisings, most were just happy to have survived, and a few bitterly pined for revenge. Only six days passed before the last of the German soldiers crossed the Rhine, on 17 November. Four days later, the French tricolour was raised in Strasbourg for the first time since the territory was annexed by the Germans in 1871.5 A rapid policy of ‘re-Gallicization’ took place in this most disputed of European territories: German place names were returned to their original French spellings, and over 111,000 Germans who had settled in Alsace during the previous forty-five years were promptly expelled, foreshadowing the century’s later ‘ethnic cleansing’.6

Twenty-one short years later, following the fall of France in 1940, the Germans were back, and promptly re-Germanized both Alsace and Lorraine, attaching them administratively to Baden-Baden on the opposite bank of the Rhine. French language, press, stamps, currency, street and place names were all re-Germanized. Those people with given names that were French had to have them changed to the German equivalent. Any inhabitants considered undesirable, including Jews, North Africans and Asians, were expelled, some 35,000 in total, the Nazi Party, police and administrators ensuring that the party ruled over all aspects of life.7

Alsace was overseen by Gauleiter (Nazi district leader) Robert Wagner, the polar opposite to Auschwitz escapee Rudolf Vrba. Whereas the latter risked his life repeatedly to save as many Jews as possible, the former set great store by killing as many Jews as possible. How did these two men born into similar middle-class homes in Central Europe become such utterly different human beings? Was it their innate characters or life circumstances that made one a fearless hero and the other a vile monster? In the First World War, Wagner had fought in Ypres, the Somme and Verdun and was wounded by gas. A chance meeting with Adolf Hitler in September 1923 captivated him and changed his life. He took part in the Beer Hall Putsch in Munich in November 1923, stood trial with Hitler and was jailed alongside him in Landsberg prison. Soon after Wagner took over as Gauleiter, Hitler told him that he wanted Alsace and Lorraine Germanized. ‘Wagner wielded the same powers in respect of Alsace as Hitler did in the rest of the Reich’, read the Allied indictment when he was arrested after the war.8 He responded with relish to the request to rid the territories of all Jews, seven train loads promptly departing for concentration camps in October 1940, with Wagner proud to report to Berlin that his was the first province in greater Germany to be ‘cleansed of Jews’. Then in June 1943, he authorized some one hundred Jews to be transferred from Auschwitz back to Natzweiler concentration camp in Alsace where they were gassed, their corpses being sent to a German professor, August Hirt, in Strasbourg for their skulls and skeletons to be studied as evidence for racial theory.9 As Allied forces advanced after D-Day, Wagner refused to give up the fight until April 1945, when he tried to flee. He was arrested by the Americans in July 1945, handed over to the French, tried, convicted and put before a firing squad at Belfort in August 1946. Unrepentant to the end, ‘Long live Adolf Hitler, long live National Socialism’ were his final words on earth.10

Vrba too stayed true to his beliefs, continuing to state for the rest of his life the uncomfortable, if contested, truth that the authorities were slow to act on their report and alert the world to the fate of the Jews departing in the cattle trucks. With 12,000 leaving Hungary every day to concentration camps after he had warned the Jewish Council in spring 1944, at least some of the 400,000 Hungarians murdered that summer might have been saved.11 His unforgiving belligerence, towards both the Allied and Jewish leaders who had not acted on his words, cost him friends and recognition: when he died in 2006, only forty people turned up to a memorial event in his honour in Vancouver.12

Robert Wagner, left, murderous Nazi ruler of Alsace, and Rudolf Vrba, right, who tried to save lives.

* * *

So here I am, ready to set off on the second walk. I’m feeling the model of a professional walker, with much suppler boots, super-dry merino socks, ultra-lightweight trousers and top, and an improved direction finder on my phone. What could possibly go wrong? I stride boldly north towards Pfetterhouse. Ten minutes later, Sarah drives past me in the car: ‘You know you’ve set off in totally the wrong direction?’ Her calm voice is quite extraordinarily irritating. ‘I am not an idiot,’ I protest. She shows me her map, I admit I am an idiot, and arrange to meet her at a location due east in four hours. An inauspicious start. I wait for her to drive off so she doesn’t see me retrace my footsteps, before walking along winding tracks to the village of Mooslargue, then setting off across fields to Riespach. My confidence takes a second hit as I’m walking on a track past a farm, and I don’t hear a small bulldog come up behind me till he has my fist in his mouth. He could have done me some harm but I think he was just seeing if I had any food in my hand: there are no teeth marks. I decide to take a track through some woods, but then totally lose the path, my map is no help, and there’s no connection to Google Maps on my phone. I listen for traffic, follow the noise and come out on a busy road, take my bag off to adjust it when an overtaking car on the other side of the road misses me by half a metre. A warning to be more careful. The day finishes along beautiful tracks and lanes into my destination, the Alsatian village of Riespach, after a walk of just over 15 kilometres.

Over a glass of Riesling with Sarah in the square, we take stock. Only now I am back walking has the truth come fully home to me that on this walk, there isn’t a No Man’s Land, no front lines, nor battles and monuments to guide me. There will be a million ways to walk to Auschwitz, and I’m having to choose one that will maximize historical learning while minimizing distance and difficult terrain. We discuss taking in a few cities, including Ulm, Prague and Nuremberg, while going the most direct way possible. As the crow flies, it is 925 kilometres. I’d be surprised, though, if it takes me less than the expected 1,300 kilometres to get there. A plane would cover the distance in an hour and a half; a car perhaps fifteen hours. But by foot? Anyone’s guess. I’ve got to take this one day at a time. But this evening, it’s a half-hour journey with Sarah navigating the car flawlessly to the Rhine village of Bad Bellingen, followed by a warm shower, dinner and bed. Fifteen kilometres might not be very much for Day 1, but I’m on my way. Only 1,285 kilometres to go!

I cannot remember a more blissful day walking along the Western Front than my second day out. I’m heading due east into the rising sun towards the Rhine. If Kent is the ‘garden of England’, then Alsace is the ‘garden of France’: I see agapanthus, bougainvillea, hibiscus, dahlias, hydrangeas, marigolds, peonies, roses and zinnias, a blaze of reds, golds, yellows and blues. The half and fully timbered houses with overhanging upper storeys have distinctive steep pitched roofs with tuiles écailles alsaciennes (flat clay tiles). All are beautifully maintained, rich in local symbols and decorations, including floral motifs and embedded woodwork in all manner of patterns, including the St Andrew’s Cross. Even in the height of summer, the aroma of burning logs lingers. As I walk, I catch glimpses of the Vosges mountains to the west, the Black Forest to the east and, further still to the south, the Alps.

As I approach the village of Uffheim, I chance upon a museum to the Maginot Line. A more futile legacy of the First World War can hardly be imagined than this pre-1939 defensive fortification. When travelling through Verdun two years before, I passed the spot where French soldier André Maginot had been wounded in 1914. While fighting, he had been captivated by the impressively resilient fortresses at Vaux and Douaumont. In the 1920s, Maginot, by now a government minister, campaigned tirelessly for a string of similar fortifications to be built along the eastern border of France. Seventy per cent of French soldiers who fought in the First World War had become casualties, and 1.4 million died, 900 for every day of the war, leaving the nation in widow’s weeds.13 Surely, Maginot asked, there was a better way to defend France, with concrete not flesh?

Fascinated, I enter the museum and find it has much to teach me about his vision. Stretching for 400 kilometres and up to 25 kilometres deep, the Maginot Line was largely completed by the time the Second World War broke out. Its singular aim was to deter a future German invasion, such as France had suffered twice in the preceding seventy years. If there was to be a war, the French soldiers would duly be hidden behind casemate and concrete, saving their precious lives. The massive Maginot defence fortifications included underground electric railways, power stations, 142 major fortresses and 5,000 blockhouses.14 Additionally, strong mobile forces – drawn from the cream of France’s army – were created to protect those parts of northern France that the defensive fortifications did not. The genius of the Maginot Line, it was argued, was that it allowed fewer men to protect more of the country, while the mobile forces could fight the Germans on their own terms.

When the war came, the line did its job superbly well; the Germans never did attack it in strength. It just didn’t matter. The Germans instead drove their tanks through the ‘impenetrable’ Ardennes forest, bypassing the mighty fortifications, before destroying the French army’s mobile forces at Sedan between 12 and 17 May 1940. As the German tanks broke through, the British forces escaped to Dunkirk, and the French government began to consider the hitherto unthinkable: capitulation.15

Not wanting, after 1945, to waste an asset into which they had pumped so much of their national wealth in the interwar years, the French remanned the Maginot Line after the fighting was over, just in case. But the advent of nuclear weapons, and the abandonment by Germany of any hostile intent to France, meant the line was mostly left to the elements from the 1960s. Now it is a monument to both folly and misjudgement.

The sun is still beating down on Day 3, 10 August. Fortified by a hearty dinner in a rural tavern in the hills above Bad Bellingen where Sarah and I were delighted to find ourselves the only English people, and by a good night’s sleep, I set out to reach the Rhine today or tomorrow, before walking into Germany. I only have to work out where to cross the river that forms a 184-kilometre border between both countries from Basel up to Lauterbourg to the north of Strasbourg. As I set off walking this morning I find myself overcome by a wave of emotion to be on the threshold of striding into Germany. True I have only walked 40 kilometres since Kilometre Zero, but putting this and the 2021 walk together, I have now walked across Belgium and France. What will Germany bring, I wonder?

My path takes me to the outskirts of a landmark city where we must linger awhile because it contains several stories that will shed light on my quest. Basel is one of Europe’s most beguiling international cities (pronounced ‘Basle’ in English), and has become the post-1945 Kilometre Zero in the sense that it is the meeting point of the same three countries, France, Germany and Switzerland. The cultural capital of the last and its third largest city (behind Geneva and Zürich), Swiss Basel blends seamlessly into German Basel and a small French town (Bâle), with the houses intertwined over the national borders quite unlike any other city on earth. Why can bricks and mortar achieve what human beings find so difficult? Basel’s deep commitment to internationalism and humanism brought a flock of leading thinkers to it throughout the ages, including early-modern Dutch humanist Erasmus, nineteenth-century German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche and twentieth-century Swiss psychotherapist Carl Jung.

Central to our story, the city is the birthplace of the State of Israel, and paradoxically the location of some of the most virulent antisemitism. Basel was chosen in 1897 as the venue for the world’s first Zionist Congress, chaired by prime mover Theodor Herzl, and it became the most popular venue for subsequent Jewish congresses until the objective was achieved, the creation of the State of Israel in 1948.

Herzl had lived in Vienna as a young man, but the rise of antisemitism promoted by demagogue and later Viennese mayor Karl Lueger convinced him that antisemitism could not be erased, that ‘assimilation’ for Jews alongside gentiles would never work, and that only a discrete Jewish homeland behind its own borders would keep Jews safe.16 He travelled to London to enlist the support of prominent Jews for his objective, but though cheered at public meetings in the East End (where my Ukrainian grandparents were to settle), his ideas met a mixed reception from the community. Despondent at the response, he decided the best way forward was to organize a World Congress of Zionists to try to win backing from Jews across the great diaspora. Munich was his first choice of venue, given the sympathetic way Jews were then treated in the city; but most Jews in the Bavarian capital were happy with assimilation, and thought that talk of a Jewish homeland was unnecessary and potentially provocative. So Herzl settled on Basel for the Congress, to which came 200 delegates from seventeen countries. After it concluded, he wrote confidently in his diary: ‘If I had to sum up the Basel Congress in one word… it would be this: at Basel I founded the Jewish state.’ Seven years later, in 1904, he died from a heart condition at age forty-four.17

Basel also has a walk-on part in a key piece in the antisemitism jigsaw. At the forefront of Herzl’s thinking about antisemitism was the experience of a Jewish Frenchman whose family had moved to Basel, to escape the German annexation of Alsace, and then to Paris, when he was still a child. Alfred Dreyfus went on to have a successful career as an artillery officer until he was arrested in 1894 and accused of selling French military secrets to Germany. Publicly humiliated, he was imprisoned until fresh evidence emerged of his innocence. The army and many at the top of French society nevertheless continued to insist on his guilt. As tensions rose, antisemitic riots broke out across France in 1898 and novelist Émile Zola published J’accuse charging the French elite with a mass cover up. Not till 1906 when Dreyfus was granted a full exoneration did the episode that had transfixed France for a decade begin to fade. The political right, though, have refused to let it be forgotten, most recently with Jean-Marie Le Pen, the late founder of France’s far-right National Front, spreading suggestions of Dreyfus’s guilt alongside outright Holocaust denial. As recently as 2021, ultranationalist politician and presidential candidate (and Jew) Éric Zemmour again questioned Dreyfus’s innocence, suggesting that ‘we will never know’ if he was guilty or not.18

Basel was centre stage, alongside the fellow Swiss city of Bern, in another vital part of the antisemitism story, the famous legal challenge to another widely promulgated lie designed to besmirch Jews and spread distrust in the mid-1930s. Two Swiss right-wingers Alfred Zander and Eduard Rüegsegger were brought to court by several local Jewish leaders, accused of insulting Jews by distributing a book called The Protocols of the Elders of Zion that had already been proven untrue and defamatory.19 It was the most influential antisemitic document of the modern era, asserting that Jews were working in secret to take over the world, to dominate world banking, to insinuate their way into every centre of power, and to divide Christendom through war and conflict. The book purported to contain verbatim reports of secret meetings of Jewish leaders planning how to achieve this end.20 The most likely source of the creation of the Protocols is the Russian secret police, the Okhrana, in 1902, in the then Russian capital St Petersburg. Why there? Because Russia at the time had the world’s biggest Jewish population, having seized Jewish-populated parts of Poland during the eighteenth century, and antisemitism was rife. Jews could only live in the ‘Pale of Settlement’, a specified area of western Russia, beyond which they were forbidden to travel. While Tsar Nicholas II, renowned for his antisemitism, was sceptical of the Protocols, saying that ‘a good cause cannot be defended by dirty means’, the text still flourished in Tsarist St Petersburg. When revolution came in 1917, many aristocrats blamed the Jews for causing it, with the result that they suffered further from ‘torture, murder and rape’ in the ensuing civil war. As one historian writes, ‘On seizing a town from the Reds, it was common for the White officers to allow their soldiers two or three days’ freedom to rob and murder the Jews at will.’21

Following the Bolshevik victory in the civil war, exiled aristocrats took copies of the Protocols with them into exile for them to be seized on gleefully by the extreme right across Europe, and in 1920, the first English translation was published in Britain. Hitler wrote in Mein Kampf in 1923, ‘To what an extent the whole existence of this people is based on a continuous lie is shown incomparably by the Protocols of the Elders of Zion.’22 For a time, the Protocols were required reading for schoolchildren in Nazi Germany. This was the background to the trial in Basel, which ended in 1936 with an out-of-court settlement. The book’s distributor Zander had to pay the court costs, and admit in writing that the Protocols had no connection with either the First Zionist Congress or the Basel Jewish leaders.23

Alfred Wiener, who spent his life documenting antisemitism and the crimes of Nazism.

Enter Alfred Wiener, a key figure in the 1930s who helped prove the Protocols were a hoax, and was deeply involved in publicizing the Bern trial.24 Born in Potsdam in 1885, he had fought proudly in the German army in the First World War. But after the Armistice he became a ferocious and forensic compiler of antisemitic writing and actions that he saw unfolding in post-war Germany and across Europe. In his belief that gathering evidence of hatred and action would alert an ignorant world to the fate of the Jews, he was a mirror image of Rudolf Vrba. Within weeks of the Nazis coming to power in March 1933, Wiener was summoned to a meeting with the newly appointed chief of the Gestapo, Hermann Göring, who demanded that he destroy his entire archive of ‘anti-Nazi’ material. Considering it too dangerous to remain in Germany, he moved his family to Amsterdam, long considered a safe haven, where his daughters became school friends of Anne Frank and her sister Margot, and where he continued to inform the world about anti-Jewish activities. However, after Kristallnacht in 1938, when Jewish shops, property and synagogues were smashed across Germany with the authorities’ active connivance, the Dutch government began to fear its tolerance of Wiener’s activities would be viewed unfavourably by the Germans. In 1939, he therefore moved his information-collecting operation to London. But his family remained in Amsterdam, and despite Wiener securing them visas, were unable to leave in time so they were soon swept up in the horrors that followed. The remarkable story is searingly recounted in the book Hitler, Stalin, Mum and Dad written by Wiener’s grandson, journalist Daniel Finkelstein.25

Before we leave Basel, I have just one final story to recount, about a figure of transcendent moral authority. While Wiener, a German Jew, had been sceptical of Herzl’s vision of a Jewish homeland in Palestine, Hermann Maas, a German ordained Christian, had been a sympathizer ever since observing the Zionist Congress in Basel. Influenced by German-Jewish theologian Martin Buber, he became a champion of Christian-Jewish reconciliation. On his return to Heidelberg after a visit to Palestine in 1933, local Nazis demanded that this ‘pastor of the Jews’ be banished from the Church. Maas became a member of the Pfarrernotbund, an association of Protestant pastors and forerunner of the Confessing Church set up by Martin Niemöller, of which more later, in opposition to the pro-Nazi ‘German Christians’ movement. When the deportations of Jews began in 1940, Maas stood up and protected some of the old and frail. The Nazis’ campaign against him intensified and resulted in his forced retirement in 1943 and banishment to a labour camp aged sixty-seven the following year. He survived to become the first German to be officially invited to visit the State of Israel in 1950, and in July 1964 he was recognized by Yad Vashem, the Holocaust Museum in Jerusalem, as one of the ‘Righteous Among the Nations’, an honorary title given to some 28,000 people, including 659 Germans.2627 For the second time on my walk, I ask myself why Wiener, like Vrba but unlike most Jews, and at great risk to himself and his family, set out to chronicle Nazi evil, and why the equally little-known Maas refused to collaborate as did so many of his fellow clergymen, and stood up boldly against the Nazis for what he knew to be right?

Pastor Hermann Maas, little-known hero, who was sent to a labour camp for saving Jews.

* * *

Leaving Basel behind, I’m back working out where best to cross the Rhine. It is not proving straightforward. There are five bridges across the river in the centre of Basel, but they are going to take me further south than I want to go. So I set my sights on crossing the enticingly named Passerelle des Trois Pays (Three Countries Bridge) on the outskirts. Built on the exact spot where a German bridge had been blown up by the French in 1797, and a German pontoon bridge was destroyed by US bombing in October 1944, it has become an emblem of the futility of conflict in this most disputed of territories. For many years after the war a passenger boat plied cars back and forth until the present bridge was completed in 2008. What more fitting passage into Germany for a walk with an international aspiration than a walk across this bridge, especially as it was designed exclusively for pedestrians and cyclists, the two categories of travellers for whom the path of peace is intended. What a celebration of physical engineering too: at 250 metres, it is the world’s longest single-span bridge intended solely for those crossing under their own steam.

The previous day, drunk on the freedom of no longer having to follow one set route, I had let my heart dictate my path through Alsatian villages as I wandered casually northwards in the direction of Uffheim. To make it back down to the tri-nation footbridge today, I face one massive obstacle that not even the advancing Allied troops had to reckon with in the autumn of 1944: the impenetrable perimeter fence of the Basel-Mulhouse-Freiburg Airport, a 4-kilometre-long presence that is taking no prisoners. Feeling I need some expert advice, I amble into my first tourist office of the trip. After a good deal of arm waving to indicate mutual fraternal feeling, they suggest I give the iconic walking bridge a miss and cross the Rhine on the next bridge downstream by walking cross-country on the path to Ottmarsheim. Joy of joys, the tourist staff tell me that, once in Germany, I will be able to buy maps showing roads with cycle tracks beside them along which pedestrians can walk with impunity. This very good news lifts my spirits. I am all too aware that, walking togs aside, I had done insufficient research on my route. Almost none, to be precise. Now I know I can walk along cycle tracks, a huge weight is lifted, and despite the sun being very hot and at its peak, the journey feels easy. From Ottmarsheim, the tourist officers suggest I cut due east, and pick up the path on the west bank of the Rhine canal that runs adjacent to the river. Had my French been better, I’m sure the path they recommended would have been easier to follow.

Readers of The Path of Peace will know that I am besotted with rivers, and be familiar with the joy I found in the seven rivers accompanying me on that earlier walk west. So I am excited that only three days into this walk, I’m naming the mighty Rhine as path of light river number one! As I write these words, I’m at our first married home into which we moved in the autumn of 2023, looking out over the Thames surging strongly downstream towards London and the sea. From my bank, I observe the river moving; but if I was the swan I see floating regally by, the river would be still and the bank would be moving. Are all moral judgements, I ask myself, relative to the point of observation, or are some moral truths, as I believe, absolute?

I think how different the Rhine and Thames are. It’s partly scale: the former at 1,230 kilometres is four times the length of the latter, falls ten times in height, and discharges a hundred times its volume of water at its mouth. The Thames with its system of eighteenth-century locks has no need of an adjacent canal to make it navigable. Navigating the Rhine to Basel with its steep gradient was always difficult and dangerous for boats. The fast-flowing waters downstream of the city were renowned as hazardous making it virtually unnavigable, and in the mid-nineteenth century, attempts were made to deepen the river that backfired by quickening the flow of the water and eroding more of the river’s base. So in the years before 1914, the German government, which then controlled both banks, decided to dig a massive canal to the west of the river from Basel to Strasbourg with hydroelectric dams installed at strategic points. The war interrupted the plans, and the Treaty of Versailles made France the exclusive controller of the project and sole beneficiary of the electricity. Known as the Grand Canal of Alsace, construction began again in 1932 and was only completed, at a length of 50 kilometres, in 1959.28

A windfall of crossing the river further to the north is that I can walk across the ground that saw the last major fighting on French soil of the Second World War. Hitler invested great importance in keeping this last slither of German-controlled Alsace in his hands, and on New Year’s Eve 1944 unleashed a major offensive in what became known as the ‘Colmar Pocket’, designed to support the larger Ardennes Offensive to the north, which was already stalling. Codenamed Nordwind, it was to be the last German offensive on the Western Front. Defending the bridges at Neuenburg am Rhein, where I am heading, and Breisach downstream, was utterly essential so German forces could keep being supplied.

I marvel at the historical symmetry of this Alsatian countryside where I am walking, which is like a ‘then and now’ photo negative of the First and Second World Wars. In August 1914, it saw the first skirmishes; in early 1945, it saw the beginning of the end. In 1914, it was high summer; in 1945, a Siberian-like winter. Then the French army was equipped with bright blue nineteenth-century uniforms with Napoleonic breastplates and swords; now drab green utilitarian kit given to them by the Americans. Then the army was horse-powered; now it was supported by tanks, armoured vehicles, trucks and aircraft. Then the French were routed; now the Germans.

The German offensive was petering out by early January 1945, and General Eisenhower, the Supreme Allied Commander, gave instructions for its remaining troops to be captured or destroyed, as he wanted Alsace to be free of all enemy forces before the Allied invasion of Germany proper began. He invited the French forces, fighting together for almost the first time on French soil since the fall of France in 1940, to join battle alongside American forces to complete the task successfully.

The French army was under the command of the flamboyant Jean de Lattre de Tassigny. Wounded five times in the fighting at Verdun in 1916, he became France’s youngest general in 1940. He remained loyal to the pro-Nazi French government in Vichy, but in 1942, when the Germans snuffed out its remaining independence, he ordered his troops to fight back, before fleeing to England and then joining de Gaulle’s Free French forces fighting in Algeria. He was destined to be the senior French commander at the signing of the German surrender in Berlin in May 1945, and on his death from cancer in January 1952, was given a state funeral in Paris that lasted five days. In him, France found the war hero its national pride so desperately needed after the country’s capitulation to the Nazis in 1940 and Vichy’s subsequent shame.29

I cross the Rhine canal by the village of Chalampé, scene of fierce fighting, crossing canal and river as directed on the Neuenburg Bridge. I stop midway over it and look down at the slow-flowing waters. I’ve arrived in Germany. I sit down by the banks and reflect again on my mission of finding acts of human goodness, not depravity, during the Second World War, before wandering into the small town of Neuenburg am Rhein, which is set back from the river, my first destination in Germany. One particular resident draws me to it. Born to aristocratic parents, like his older brother who became a fighter pilot, he served throughout the First World War, fighting at Ypres before being wounded in the war’s final months. He developed a particular aversion to Hitler, and moved to Vienna then to Prague when war broke out.

Albert Göring hoped his brother Hermann, Luftwaffe supremo and right-hand man to Hitler, would protect him. Famously, after the German annexation of Austria in 1938, the SA (Sturmabteilung, storm troopers or ‘brown shirts’) forced Jews to scrub the streets. On one occasion, Albert joined them, getting down on his knees alongside the Jews, the SA knowing that they could not touch him, even after he was later known to have helped some escape to safety. When arrested by the Allies in 1945, he was saved from harm by the testimony of survivors. After the war, when his family name was toxic, he shunned publicity and became an alcoholic before dying in 1966 in Neuenburg an unknown, his anti-Nazi deeds unacknowledged. His last act was one of kindness, to marry his hard-up housekeeper, knowing that his state pension would be transferred to her on his death.30

The two Göring brothers, Albert on the left and Hermann on the right.

A degree of uncertainty surrounds exactly how far Albert went to save Jewish lives. One biography is named Thirty-Four, supposedly the number of lives he saved, leading to a flurry of headlines suggesting ‘Göring’s brother was another Schindler’.31 Pressure was placed on Yad Vashem to honour him with the designation ‘Righteous Among the Nations’, but it declared in 2016 that though there was evidence of him helping some Jews, there was a lack of ‘primary documentation’ proving he had taken extraordinary risks to do so.32

The full truth may never be known. But it is beyond doubt that Albert didn’t follow his brother into the Nazi Party, that he defended and protected others who were vulnerable at significant risk to his livelihood if not to his actual life. Hermann said of him: ‘He was always the antithesis of myself. He was not politically or militarily interested; I was. He was quiet, reclusive; I like crowds and company.’33 How can the same parents bring up one monster and another who stands up against evil and protects the vulnerable? Canadian physician Gabor Maté says ‘no two children have the same parents’.34 Both brothers may well have experienced totally different parenting, but both made their choices as adults. An early conclusion emerging is that, whatever the disadvantages people may have endured, we are all responsible for our acts.

My day ends walking for two hours south along the riverside path from Neuenburg am Rhein to Bad Bellingen. I don’t pass a single walker, but my eyes keep pinned to the river, a short distance below me, visible periodically through the trees. It is our last night at the Kurhotel Markushof in Bad Bellingen, a welcoming family hotel for the first sojourn on this new trip, many leagues above the places I rested my weary body on the Western Front. In the morning, Sarah drives me back to Neuenburg am Rhein from where I walk by the side of the Rhine to Breisach, a hill city I remember from History A Level. A strategic stronghold commanding the river, it was held by the Habsburg-led Holy Roman Empire till lost in the Thirty Years War and ceded to France at the Peace of Westphalia in 1648. Because I had zipped up the 20-kilometre walk in four hours, we are able to meet for lunch in Breisach’s market square, and I am able to fulfil what I had long promised Sarah: walking in the morning and spending the rest of the day together. There is scant evidence today that most of the town was destroyed in the battle in January and February 1945. But it is the earlier history that captures our attention as, even in this land of alternating control, it set new standards. In brief, Breisach was French from 1648, returned to the Habsburgs in 1697, French again in 1703, returned to the Habsburgs in 1714 (which led France to create the Vauban-inspired magical fortress town of Neuf-Breisach on the western side of the river), then retaken by Germany in 1871, and so on, and on…35