Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Atlantic Books

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

*THE INSTANT #1 SUNDAY TIMES BESTSELLER* 'Enticingly structured... Commendable... The menu is well known, but is deliciously seasoned all the same.' The Times [A] forensic and eloquent evisceration of Truss's chaotic and catastrophic 49 days in No 10' Independent 'A textbook on bad government' Dominic Grieve, Guardian The shortest-serving prime minister in history. The first former leader to lose their seat since 1935. An inside look at how it all went so wrong. Liz Truss's disastrous premiership was the shortest and most chaotic in British history. In the space of just 49 days, Truss witnessed the death of the longest-reigning monarch, attempted to remould the economy, triggered a collapse in the value of Sterling and was forced on a series of embarrassing U-turns that ultimately led to her resignation. The aftershocks of her time in office are still felt today. How did she blow her opportunity so spectacularly? Based on exclusive interviews with key aides, allies and insiders, and focusing on the critical steps that led to her demise, this gripping behind-the-scenes work of contemporary history gives the definitive account of Truss's premiership. Number 1 Sunday Times Bestseller, 8 September 2024

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 545

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

‘The leading authority on our contemporary prime ministers… His research has been extensive and the commentary is fleshed out with dialogue and quotations, which he assures us have been checked for accuracy and make for compelling reading. His verdict is harsh’ Guardian

‘One of the best observers of modern politics… The book surprises, thanks to a clever device that turns it into more of a manual for her successors’ Financial Times

‘Enticingly structured… The menu is well known, but is deliciously seasoned all the same’ The Times

‘Contains candid on-the-record interviews with many of those involved… The book provides fresh insights into the personal tensions, “character flaws”, and behind-the-scenes clashes that contributed to her downfall’ Independent

‘This is a brisk and readable account… The voters of South West Norfolk finally ended Truss’s parliamentary career in July. Those who read this book may well think they spoke for Britain’ Observer

‘Written with swashbuckling historical perspective and panache, Anthony Seldon has produced an intimate account of an unparalleled British psychodrama’ PoliticsHome

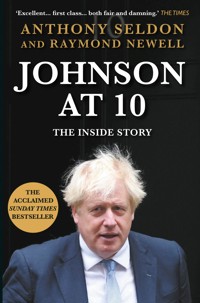

Sir Anthony Seldon is an educator, historian, writer and commentator. A former headmaster and vice chancellor, he is author or editor of over fifty books on contemporary history, politics and education, including Johnson at 10, The Impossible Office?, May at 10, Cameron at 10, Brown at 10, Blair Unbound and The Path of Peace. He’s been co-founder of Action for Happiness and the Institute of Contemporary British History, and is founder of the Museum of the Prime Minister.

___________

Jonathan Meakin was educated at Royal Holloway, University of London and at the University of St Andrews. He is a professional researcher and has worked on many publications including The Cabinet Office, 1916–2016 and The Impossible Office?. He has also worked as a researcher on political and historical topics. He has worked at historical sites in Britain and as a volunteer in the United States.

First published in hardback in Great Britain in 2024 by Atlantic Books, an imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd.

This paperback edition published in 2025 by Atlantic Books.

Copyright © Anthony Seldon, 2024, 2025

The moral right of Anthony Seldon to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

No part of this book may be used in any manner in the learning, training or development of generative artificial intelligence technologies (including but not limited to machine learning models and large language models (LLMs)), whether by data scraping, data mining or use in any way to create or form a part of data sets or in any other way.

The illustration credits on p. 349 constitute an extension of this copyright page.

Every effort has been made to trace or contact all copyright-holders. The publishers will be pleased to make good any omissions or rectify any mistakes brought to their attention at the earliest opportunity.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Paperback ISBN: 978 1 80546 216 3

E-book ISBN: 978 1 80546 215 6

Printed in Great Britain

Atlantic Books

An imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd

Ormond House

26–27 Boswell Street

London WC1N 3JZ

www.atlantic-books.co.uk

CONTENTS

Dramatis Personae

Preface to the Paperback Edition

Prologue

Introduction

1 Secure the Power Base

2 Have a Clear and Realistic Plan for Government

3 Appoint the Best Cabinet/Team

4 Command the Big Events

5 Be Credible and Highly Regarded Abroad

6 Learn How to Be Prime Minister

7 Avoid Major Policy Failures

8 Maintain a Reputation for Economic Competence

9 Avoid U-turns

10 Retain the Confidence of the Party

The Verdict: ‘Deep State’ or Deep Incompetence?

Acknowledgements

Notes

Illustration Credits

Index

Boris Johnson and Liz Truss were united on little, in truth, except their hostility to Rishi Sunak and hunger for power

DRAMATIS PERSONAE

Liz Truss: Prime Minister (6 September 2022–25 October 2022) Also: MP for South West Norfolk (Conservative, 2010–24), Parliamentary Under-Secretary for the Department of Education (2012–14), Justice Secretary and Lord Chancellor (2016–17), Chief Secretary to the Treasury (2017–19), International Trade Secretary (2019–21), Foreign Secretary (2021–22)

Hugh O’Leary: Husband of Liz Truss (2000–)

Cabinet

Edward Argar: (attending Cabinet) Chief Secretary to the Treasury (14 October 2022–25 October 2022), Paymaster General and Minister for the Cabinet Office (6 September 2022–14 October 2022)

Kemi Badenoch: Secretary of State for International Trade (2022)

Jake Berry: Minister without Portfolio (2022), Chairman of the Conservative Party (2022)

Suella Braverman: Home Secretary (6 September 2022–19 October 2022)

Robert Buckland: Secretary of State for Wales (2022)

Simon Clarke: Secretary of State for Levelling Up, Housing and Communities (2022)

James Cleverly: Foreign Secretary (2022–23)

Thérèse Coffey: Deputy Prime Minister (2022), Health Secretary (2022)

Michelle Donelan: Secretary of State for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport (2022)

Michael Ellis: (attending Cabinet) Attorney General for England and Wales, and Advocate General for Northern Ireland (2022)

Vicky Ford: (attending Cabinet) Minister of State for Development (2022)

James Heappey: (attending Cabinet) Minister of State for the Armed Forces and Veterans (2020–24)

Chris Heaton-Harris: Secretary of State for Northern Ireland (2022)

Jeremy Hunt: Chancellor of the Exchequer (14 October 2022–5 July 2024)

Alister Jack: Secretary of State for Scotland (2019–24)

Ranil Jayawardena: Secretary of State for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (2022)

Kwasi Kwarteng: Chancellor of the Exchequer (6 September 2022–14 October 2022)

Kit Malthouse: Secretary of State for Education (2022)

Penny Mordaunt: Leader of the House of Commons, Lord President of the Council (2022–24)

Wendy Morton: (attending Cabinet) Chief Whip to the House of Commons (2022)

Chris Philp: (attending Cabinet) Chief Secretary to the Treasury (6 September 2022–14 October 2022), Paymaster General and Minister for the Cabinet Office (14 October 2022–25 October 2022)

Jacob Rees-Mogg: Secretary of State for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy (2022)

Grant Shapps: Home Secretary (19–25 October 2022)

Alok Sharma: President for COP26 (2021–22)

Chloe Smith: Secretary of State for Work and Pensions (2022)

Graham Stuart: (attending Cabinet) Minister of State for Energy Security and Net Zero (2022–24)

Lord True: Leader of the House of Lords (2022–24)

Tom Tugendhat: (attending Cabinet) Minister of State for Security (2022–24)

Ben Wallace: Secretary of State for Defence (2019–23)

Nadhim Zahawi: Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster (2022), Minister for Intergovernmental Relations (2022), Minister for Equalities (2022)

Advisers

Asa Bennett: Speechwriter (2022)

John Bew: Foreign Affairs Adviser to the Prime Minister (2019–24)

David Canzini: Deputy Chief of Staff (October 2022)

Iain Carter: Director of Strategy (2022)

Clare Evans: Director of Operations (2022)

Mark Fullbrook: Chief of Staff (2022)

Jamie Hope: Director of Policy (2022)

Sophie Jarvis: Political Secretary (2022)

Adam Jones: Political Director of Communications (2022)

Sarah Ludlow: Head of Strategic Communications (2022)

Simon McGee: Director of Communications (2022)

Adam Memon: Economic Adviser (2022)

Shabbir Merali: Economic Adviser (2022)

Ruth Porter: Deputy Chief of Staff (2022)

Matthew Sinclair: Chief Economic Adviser (2022)

Jason Stein: Special Adviser (2022)

Members of Parliament

Graham Brady: Chair of the 1922 Committee (2010–24), MP for Altrincham and Sale West (Conservative, 1997–24)

Mark Francois: MP for Rayleigh and Wickford (Conservative 2010–, MP for Rayleigh 2001–), Chair of the ERG (2020–)

Philip Hammond: MP for Runnymede and Weybridge (Conservative, 1997–2019), Foreign Secretary (2014–16), Chancellor of the Exchequer (2016–19)

Sajid Javid: MP for Bromsgrove (Conservative, 2010–24), Home Secretary (2018–19), Chancellor of the Exchequer (2019–20), Health Secretary (2021–22)

John Redwood: MP for Wokingham (Conservative, 1987–24)

Craig Whittaker: MP for Calder Valley (Conservative, 2010–24), Deputy Chief Whip (2022)

Gavin Williamson: MP for South Staffordshire (Conservative, 2010–24, MP for Stone 2024–), Chief Whip (2016–17), Defence Secretary (2017–19), Education Secretary (2019–21)

Officials

Andrew Bailey: Governor of the Bank of England (2020–)

Tim Barrow: National Security Adviser (2022–)

James Bowler: Permanent Secretary to the Treasury (2022)

Simon Case: Cabinet Secretary and Head of the Civil Service (2020–)

Nick Catsaras: Principal Private Secretary to the Prime Minister (2022)

Jon Cunliffe: Deputy Governor for the Bank of England for Financial Stability (2013–23)

Stuart Glassborow: Director to HM Treasury (2022–23)

Richard Hughes: Chair of the Office for Budget Responsibility (2020–)

Catherine (Cat) Little: Acting Permanent Secretary to the Treasury (2022)

Clare Lombardelli: Chief Economic Adviser, Joint Head of the UK Government Economic Service (2018–23)

Antonia Romeo: Permanent Secretary at the Ministry of Justice (2021–)

Beth Russell: Acting Permanent Secretary to the Treasury (2022)

Tom Scholar: Permanent Secretary to the Treasury (2016–22)

Edward Young: Private Secretary to the Sovereign (2017–2023)

PREFACE TO THE PAPERBACK EDITION

The hardback of this volume, predictably perhaps, caused a storm when it was first published in September 2024. No book about Britain’s messiest premiership would do anything else. Liz Truss herself attacked the book but contested just one point – whether cuts in cancer treatments were on a list put to her of possible responses to the deep peril that her mini-budget had unleashed. But the facts are exactly as laid out in the book. If a Prime Minister places the country in a dangerous position, as she so carelessly did, the system will throw up desperate remedies to restore the status quo – cancelling the prison building programme was another possible choice on the cuts list. Her staff, indeed, became acutely worried about what cuts an increasingly desperate Truss might agree to.

Since she left Downing Street, rather than showing any remorse or apologizing, she has doubled down on the rightness of her decisions. In doing so she fails to discriminate between her policy objectives – economic growth – which was very obviously correct for the country after fifteen years without it, and her own presentation of her strategy – its timing and her handling of the politics – which were utterly incompetent.

Her brazen lack of contrition has lost sympathy and done further damage to her reputation. National leaders have a duty to tell the truth, not least about national institutions. Her actions since October 2022 are a source of sadness and regret, not least to those who served with her. What a Prime Minister does after they leave office matters, if a lot less than what they did during it.

One particular accusation made by her and her supporters has not gone away and thus needs to be tackled head on: the claim that she was brought down by the establishment (or ’blob’), specifically the Bank of England and the Treasury, which sabotaged her and Kwasi Kwarteng’s mini-budget. The charge is that these institutions connived to hide the impact of a negative market reaction from her because, she believes, they are anti-growth, big spending socialists or pro-bureaucracy – or perhaps a mix of all three. Wokery was the glue binding her enemies together, she asserts, denying her the rest of her Premiership and resulting in her replacement with Sunak, who she claims performed much less well in the 2024 general election than she would have done if still leader.

Her indignation exploded in her book published in early 2024, Ten Years to Save the West. Then, in January 2025, she accused the Bank of England, the establishment and media of smearing the mini-budget, and warned Prime Minister Keir Starmer to stop accusing her of ‘crashing the economy’. As dedicated free marketeers, she and her supporters find it hard to admit that it was her own misreading of the markets that brought about her downfall. While aspects of the establishment’s handling of the firestorm unleashed by the mini-budget can legitimately be questioned, the charge that the Treasury and Bank of England conspired to bring her down has to be rejected as dangerous and delusional.

Writing such a critical book of such a forthright and irrepressible, if flawed, leader gave me no pleasure. But there’s no escaping the damage her folly did, which fresh events and research since the hardback publication only highlight. She damaged the Conservative Party: election guru John Curtice has argued that although the dip in the party’s fortunes may have started during the Owen Paterson and party-gate mishandlings under Johnson, it consolidated in reaction to her financial upheavals. She also damaged trust in government; the disillusion with conventional political parties she exacerbated fed the popularity of Reform UK and damaged social cohesion. One-time anti-extremism tsar Sara Khan revealed in a December 2024 report that nearly half of those questioned said they no longer trusted the government to put the nation’s interests first, a number which has doubled since 2020 – before the follies of the Johnson and Truss Premierships.

The ways Truss damaged the country can even be observed in the current Labour government. Two particular actions under Keir Starmer, neither optimal, can be directly traced to the fallout of her governance. The negative reaction to her counter-productive dismissal of Tom Scholar, the Permanent Secretary to the Treasury, delayed Starmer making vital changes to his own officials, and Chancellor Rachel Reeves’s early announcements, notably scrapping the winter fuel allowance for many, are a clear attempt to reassure the financial markets that, unlike Truss and Kwarteng, she is tough on controlling spending.

The irony of Truss’s premiership is that she damaged the very cause that she most tried to champion, economic growth, and which her lodestars Margaret Thatcher and Ronald Reagan succeeded in achieving because, unlike her, they understood leadership.

Anthony Seldon, January 2025

PROLOGUE

She came, she saw, she crashed.

In the three centuries of the history of the British Prime Minister, there has never been a premiership like that of Liz Truss. She had promise: the most experienced incomer in thirty-two years, with high intelligence, a clear plan and the right focus diagnosed: growth. Britain has had short-serving Prime Ministers before. But nowhere else in our long history has a Prime Minister arrived in power, so spectacularly mishandled an ambitious agenda, detonated an economic crisis, reversed their policies and fallen from power in less than fifty days. It paved the way for the worst Tory general election result in history in July 2024. We shall not see her like again.

‘How could this have happened?’ I asked myself, as did so many others. Wasn’t Britain supposed to be a ‘well-governed nation’? How on earth, I wondered, had the British democratic system, the oldest and most tested in the modern world, thrown up Liz Truss?

And so it was, just ten months after becoming Prime Minister, and nine after leaving it, Liz Truss was standing in front of me and asking, ‘Why are you writing a book on me?’

I was taken back by the forcefulness of the question. I didn’t know exactly how to respond. But she gave me no opportunity.

‘I’m writing my own book, you know.’ She looked at me fiercely.

‘I’m glad,’ I blurted out. And off she strutted.

It was Wednesday, 5 July 2023, at the Spectator summer party in Central London and this was the first time I had spoken to Liz Truss.

Since her mesmerizing fall from power some months earlier, I had lost count of the number of people who had asked me, ‘Are you going to be writing a book about Liz Truss?’ Then the inevitable follow-up: ‘I bet it will be a short one!’ Well, maybe I should, I thought.

Liz and I may not have met before; but we had history.

She was an admirer of the Institute of Economic Affairs (IEA), which had been established in the 1950s by my father Arthur Seldon. He always insisted, in contrast to his co-founder Ralph Harris, that the IEA stay above party politics: a think tank, not a pressure or spouting tank. It expounded the virtues of the free market and anti-statist thinking that had become her lodestar. Had my father unwittingly helped forge Liz Truss’s thinking? Almost certainly.

Fifty years before she came to prominence, another ambitious provincial woman had risen up through the Conservative Party, inspired by the same liberal ideals. Margaret Thatcher had few mentors or historical precedents for the kind of leader she wanted to be, and certainly none of her own sex. But Truss saw in her a pioneer from whom she could draw inspiration, who had gone on to change, as she considered herself destined to do, the entire course of British history.

Truss was born in July 1975 in the city of Oxford where I was a student ending my second year. I had spent my first summer holiday in 1974 working in the Centre for Policy Studies, newly minted by Thatcher to champion free-market ideas. How could one leader get things so right, and the other, so catastrophically wrong?

Another link to Truss was far more recent. Her chief of staff, Mark Fullbrook, had contacted me about my work on how to characterize and optimize successful premierships. He told her about an analysis I had produced in 2017, and when in No. 10, showed her special advisers a BBC film of me talking about it. Here, after forty years of writing about Prime Ministers, was my first opportunity actually to shape a premiership. A week before she entered No. 10 in September 2022, I had published an article in the New Statesman outlining the ten dangers that had ensnared previous Prime Ministers, and how she might circumvent them.1

Had I in some small part helped create Liz Truss?

It seemed, given her abject failure in office, that she had succumbed to the very dangers I had outlined. But to my dismay and discomfort, she took almost all of my advice on board, by design or, almost certainly, by accident.

‘Secure the citadel’ by appointing a crack team in Downing Street was advice she followed to an extreme degree by appointing ultra-loyalists. Next up was ‘Find your authentic voice early on’. She did indeed. She was not remotely bashful or faltering about what she wanted to do. ‘Macro then micro’, i.e. stick with the big themes and don’t get distracted, was counsel she honoured to the letter. ‘Control your time and make others do the detail.’ Another tick. In fact, to the consternation of her team, she cancelled endless meetings that she deemed irrelevant. ‘Control your Cabinet tightly.’ She kicked aides out of meetings and gave dire warnings to her ministers about misbehaviour and leaking. ‘Have a big fight with the media early on and win: don’t become ensnared in their agenda’. She banished newspapers from her office, squared up to the media… but then lost the big fight. ‘Play the part of PM with style.’ She did, promptly seeing off Britain’s longest-serving monarch and conducting herself diligently through all the events of mourning. ‘Seize the big moments and command them.’ She didn’t just seize the big moment, she made it totally her own and sprayed it in garish colours: the Mini-Budget, the most controversial for forty years, was hers, not the Chancellor’s. ‘Simplify, and be lean.’ She was spare to the point of wasting away: she had one big theme only, growth, and was lean and mean in its pursuit. Finally, ‘work with your Chancellor and avoid pointless battles’. She did work closely, all love and harmony – until she sacked him.

I realized I would need a different approach to explain prime ministerial failure to encompass ‘outlier’ Prime Ministers like Truss (and Johnson). I sought refuge in the more recent ‘impossible office’ analysis I’d written about in 2021: might that be better at explaining her? Or would Liz Truss defy that approach too?

I decided I would shape the whole chapter structure around the ten fields of this new approach to see if it might explain why her premiership went wrong so quickly and so spectacularly. I would also have to delve far deeper into history than my earlier analysis, right the way back to Walpole’s appointment as first Prime Minister in 1721.

I had to write this book. In part to try to understand what went wrong with Truss’s bold project, but also to offer a robust and contemporary guide to students and practitioners on how, and how not, to be Prime Minister.

This book, the eighth in the series on Prime Ministers, was written while I unexpectedly found myself back running a school, Epsom College, after the tragic death of the Head. School came first, second and third. The book is dedicated to all at the school.

Anthony Seldon, July 2024

Truss modelled herself on the iconography of Margaret Thatcher, if not her statecraft. Here in Estonia as Foreign Secretary on 30 November 2021

The Sunak team expected Truss to self-implode on the leadership campaign

INTRODUCTION

The office of Prime Minister is the highest position a non-royal can aspire to in the United Kingdom. Since the office was created in April 1721, some 200 million subjects have fretted their ways through Britain’s towns and countryside, but only fifty-eight of them arrived at the door of 10 Downing Street to claim the keys.

1 in 4 Million

Put another way, only 1 in every 4 million Britons over those three centuries rose to be PM, and most of them were drawn from a narrow aristocratic elite. Countless politicians aspired to it and some of the very best fell short.1 For Liz Truss to have been appointed Prime Minister on 6 September 2022 as the last public duty of Queen Elizabeth II was by any standards remarkable. The significance of it was not lost on the younger Elizabeth. Her achievement was unusual for more than not being male or born with a silver spoon in her mouth. Most Prime Ministers had come to office without a very precise programme to enact. Sufficient for many was the premiership itself, content as they were to govern the country responding to, rather than deliberately trying to shape, events. But Truss saw herself in the mould of one of her heroes, Winston Churchill, ‘walking with destiny’ to fulfil her own historic mission – to save her country from years of torpor and decline.

Once appointed, the top priority for all Prime Ministers is to remain in office. It’s difficult to achieve. Barely any since 1900 have left at a moment entirely of their own choosing. But Truss arrived with advantages her recent peers lacked, including extensive Cabinet experience, a full six weeks to prepare for office with top civil service brains on tap and a seemingly impregnable position as Conservative leader – we’ll explore that later – on top of her ferociously clear mission. After a run of inconclusive premierships, she believed she was going to buck the trend. She’d arrived and everyone had better watch out.

Her plan was high risk and eminently precise, on paper. In her own words, ‘I wanted to concentrate above all on the economy and generating growth. That was my focus until the general election in two years. I knew I’d never have more political capital than at the start. Then, when I won my own election mandate, I would turn my focus for the following five years onto all the other areas like education that badly needed fixing.’2 She abhorred what had happened to the country under Labour’s Tony Blair (1997–2007) and Gordon Brown (2007–10), including granting too much independence to the Bank of England, and the ‘furring up’ of enterprise and institutions.

As a Cabinet minister under David Cameron (2010–16), Theresa May (2016–19) and Boris Johnson (2019–22), she had watched as, one after the other, they crashed and burned, their missions incomplete. Johnson was the leader she had most enjoyed working for, but she was frustrated he didn’t do more to deliver the Brexit dividends. She was not going to make the same mistakes. There would be no pussyfooting, no indecision and no lack of courage: she was going in all guns blazing, like Churchill no less, demanding ‘Action this day’, or Margaret Thatcher, who early on in her premiership abolished exchange controls in her fight for freedom.

The average length in office of the Prime Minister over the 300 years has been four years and nine months, or 1,734 days. Truss had a decent chance of lasting considerably longer than that. Even sceptics assumed that, after the early departures of Cameron, May and Johnson, and with a significant majority, the Conservative Party wouldn’t be so rash as to prematurely unseat a fourth. She may have had few ideological fellow travellers, or MPs who liked her personally, but even her enemies – of which there were many – conceded that she would last at least until the general election at some point in 2024. Given the healthy majority of eighty won by Johnson in December 2019, a Truss victory in 2024, even with a reduced number, didn’t seem impossible against an apparently lacklustre Labour leader in Sir Keir Starmer presiding over a still-divided party. But Truss knew that victory would rest on the economy picking up – hence her push for economic growth.

Yet, just forty-nine days later, she and her project had self destructed.

How Unusual was Truss’s Brevity?

We know now that hers was the shortest premiership of any British Prime Minister. While seven other premiers since 1721 served less than a year in post, and a further seven less than two years, none had fallen anything like as quickly. Her brevity in post rapidly became a standing joke across the country – the Daily Star memorably comparing it to the shelf life of a lettuce. But how unusual was it?

Dig below the surface, and look abroad, and fleeting leaderships are not necessarily unusual.

Last century, the Conservative Stanley Baldwin (1923–24, 1924–29, 1935–37) and Labour’s Ramsay MacDonald (1924, 1929–35) served less than a year in their first periods as Prime Minister, in 1923 and 1924 respectively, before coming back for longer stints. They were aged fifty-five and fifty-seven when they first became PM; Liz Truss was ten years their junior. Unlikely though it may seem, no one can rule out her coming back as Prime Minister at some point in the future, expunging forever the unwanted moniker of ‘Britain’s shortest-serving Prime Minister’. After all, three of the most significant Conservative premiers of the nineteenth century, Robert Peel (1834–35, 1841–46), Benjamin Disraeli (1868, 1874–80) and Lord Salisbury (1885–86, 1886–92, 1895–1902) all served less than a year in their first spells as Prime Minister, at 120, 279 and 220 days respectively. While Peel was the same age as Truss, Disraeli and Salisbury were considerably older and age was more of a handicap back then.

Besides, one might argue, it’s parochial to disparage Truss’s forty-nine days as absurdly short. Looking abroad, we find American President William Henry Harrison served for only thirty-one days in the White House. He suffered from severe ill health and died in April 1841 following crude medical procedures that included bloodletting (the deliberate loss of blood believed to be restorative). President James Garfield served 199 days before dying in September 1881 from the wounds inflicted by an assassin’s bullet at Washington’s Potomac & Baltimore railway station seventy-nine days earlier. The President was attended by his Secretary of War, Robert Lincoln, reawakening traumatic memories of the assassination in the same city sixteen years before of his father Abraham. Neither Harrison nor Garfield can be held responsible for the brevity of their tenures; in both cases, however, their doctors might have been.

Truss’s stay appears positively leisurely compared to Spain’s leading politicians. Of the 102 Spanish Prime Ministers since the office was established in 1823, sixty-six were gone within a year. Nine lasted ten days or less, mostly during the revolutions, civil wars and political upheavals of the nineteenth century.

Elsewhere, though, Europe offers little solace to her. Even Italy, notorious in English minds for serial political instability, saw its shortest-serving post-1945 Prime Minister, Fernando Tambroni, lasting a heroic 116 days3 in mid-1960 before his supporters abandoned him. Longevity was often elusive among Commonwealth leaders. Four of Canada’s twenty-three Prime Ministers since 1867 served less than a year, albeit none as fleetingly as Truss. While Australia has seen six of its thirty-one Prime Ministers since 1901 survive less than a year, three of them came in purely as caretakers. It is to this country that we must look to find a leader who served shorter than Truss. Arthur Fadden stepped up in August 1941 after the stalwart PM Robert Menzies departed, only to resign after six weeks. He later quipped that he had, rather like the Biblical flood, ‘reigned for forty days and forty nights’.4 Some consolation for Truss can also be found in the claim that she is not technically Britain’s shortest-serving Prime Minister. In 1746 Lord Bath and in 1757 Lord Waldegrave were appointed First Lord, but neither had enough political support, resigning within a few days. Back then, there was more debate about what constituted a Prime Minister. Lord North (1770–82) refused to be called ‘Prime Minister’, arguing that ‘there is no such thing in the British Constitution’, and it was not until Robert Peel in 1846 that the incumbent referred to themselves as ‘the Prime Minister’. The term remained constitutionally imprecise until it began to be used in official language at the beginning of the last century.5 When George I appointed Robert Walpole (1721–42) in April 1721, it was not to the job of ‘Prime Minister’, an office that did not exist, but to ‘First Lord of the Treasury’, the name that still appears on the letterbox of the front door of 10 Downing Street, an address into which Walpole moved only in 1735 in his fifteenth year in office.

Truss’s blushes might also be spared by acknowledging that many Prime Ministers have faltered early in their premierships – yet they survived, if often as much through luck than judgement. Even several of the nine ‘top tier’ or great Prime Ministers wobbled badly with early difficulties. Walpole was just over a quarter of the way through his office in June 1727 when he faced his severest challenge, the death of George I and the succession of his son, George II, at a time when the monarch was still the arbiter of the head of government. Walpole had admittedly already served for six years, but it was only by stealth and by milking his astute friendship with the new Queen that he ingratiated himself with the new King. Walpole went on to serve for another fifteen years.

William Pitt the Younger’s (1783–1801, 1804–06) early travails arguably eclipsed those of Liz Truss because his position was precarious from day one. When George III invited him to become Prime Minister on 19 December 1783, one wag described it as the ‘mince pie administration’ as no one expected it to last beyond Christmas, an analogy deployed by Chair of the 1922 Committee Sir Graham Brady in Truss’s final days. Between January and March 1784, the continuation of his premiership was in doubt with many of the big beasts, not least Charles James Fox, Edmund Burke and ex-Prime Minister Lord North, ranged against him. He was defeated in important votes in January, with his support from Cabinet wavering: ‘for six weeks, now, the country had had a government, with no power to govern’, wrote his biographer William Hague.6 But Pitt used all his powers of persuasion, parliamentary chicanery and, crucially, patronage to strengthen his ministry and lay the groundwork for a general election. Critically, Pitt retained the confidence of the King, and in March 1784, he felt strong enough to announce the election that resulted in his supporters winning some seventy seats.7 At last he was secure. Pitt went on to serve another seventeen years as Prime Minister.

Other examples abound, not least Churchill (1940–45, 1951–55), whose position as Prime Minister remained vulnerable after his appointment in May 1940 as the war news darkened and Cabinet discussed whether to continue fighting. Margaret Thatcher’s (1979–90) insecure first three years were not finally firmed up till victory in the Falklands War of 1982. Well might Truss rue bowing to advice to U-turn on her economic package, a course her belle idéale conspicuously rejected in October 1980. Had she too stood her ground, could she have come through, and like her Conservative predecessors, been in power for many years more?

Alas for her, it did not happen, and she can only cling to her belief that she was betrayed, and that, one day, the great crusade she had started will triumph.

Why Do Prime Ministers Fall?

For the rest of us, we have to make sense of one of the greatest puzzles in prime ministerial history. Why did a PM with a strong parliamentary majority, a credible track record of ministerial experience, and who knew their own mind, fall at such speed? The best place to look for clues is the reasons why other short-serving Prime Ministers fell.

General election defeats are the most frequent cause. Alec Douglas-Home (1963–64) had been at No. 10 for just less than a year when the five-year electoral cycle compelled him to call a general election for 15 October 1964. The Conservatives had previously won convincing victories in 1955 (sixty-seat majority) and 1959 (hundred-seat majority) and looked in a strong position. But Labour had acquired a new dynamism and appeal after Harold Wilson (1964–70, 1974–76) took over as leader in February 1963. The general election eighteen months later proved surprisingly close. Only on the following afternoon was the result known: a Labour victory with a majority of four. At just 363 days at No. 10, Home became the eighth shortest-serving Prime Minister, albeit within a whisker of serving longer.

At two years and 318 days, Gordon Brown is Britain’s twenty-first shortest-serving PM. After the May 2010 election, he tried for four days to stay on as head of a coalition government in partnership with the Liberal Democrats. Ultimately he was unsuccessful. He might have surged up the longevity league table had he not backed off calling an early general election in the autumn of 2007. We will never know what might have happened had Brown held his nerve. No doubt the prospect, if he had lost, of becoming one of Britain’s shortest-serving Prime Ministers tipped him towards caution. What we do know is that Liz Truss emphatically ruled out any early general election, and that electoral defeat doesn’t explain her demise.

Illness, exacerbated by the strains of office, the elusiveness of rest and the unusually high exposure of the PM to germs have been factors in many departures. William Pitt the Elder saw his premiership increasingly bedevilled by illness, including gout and mental health problems felt by contemporaries to border on insanity. Pitt decided in October 1768, having barely governed at all for a year, that he had had enough, resigning on grounds of ill health, the seventeenth shortest-serving Prime Minister at just two years and seventy-six days.

Liberal Henry Campbell-Bannerman (1905–8) led his party to its greatest victory in the 1906 general election, setting the scene for one of its most reforming administrations. Aged sixty-nine when he became Prime Minister, he suffered the death of his wife that August, and a serious heart attack in November of the following year. In March 1908, a concerned Edward VII visited him at No. 10, making it clear that, under all circumstances, a change of premier should be avoided while the King was on holiday. But when Campbell-Bannerman’s health deteriorated further, the King summoned Herbert Asquith to Biarritz in the South of France in early April to invite him to take over as Prime Minister. The bedbound Campbell-Bannerman was allowed to remain in Downing Street, where he died two weeks later. ‘The doctor going in, and the priest coming out; and as I reflected on the dying Prime Minister, I could only hope that no sound had reached him of the crowd that cheered his successor,’ recorded Asquith’s wife Margot. Serving two years and 122 days, he was the nineteenth shortest-serving Prime Minister.8

Truss certainly did not suffer from physical illness, though some close to her have speculated whether she had a nervous breakdown in her final days in No. 10. This might have impaired her judgement and precipitated her departure, a thesis we examine in this book. We also examine the thesis that her impetuosity was fuelled by excessive caffeine, or even a regular glass of Sauvignon Blanc, her favourite tipple.9

What other factors are behind brief premierships? Death in office was responsible for the departures of several including twelfth shortest-serving Prime Minister, the Marquess of Rockingham (1765–66, 1782) in 1782 after a second administration lasting ninety-six days (for a grand total of one year and 113 days), and the thirteenth briefest, the Earl of Wilmington (1742–43) after one year and 119 days. None of the short-servers was more intriguing a character, though, than the man who for nearly 200 years wore the unwanted mantle of Britain’s shortest-serving PM, George Canning, who survived just 119 days. One of the great might-have-beens, Canning towered over many of his prime ministerial peers in terms of ability and imagination. A formidable Foreign Secretary during and after the Napoleonic Wars, he was already ailing when George IV invited him in April 1827 to become Prime Minister in succession to Lord Liverpool. With politics riven by the issues of parliamentary reform and Catholic emancipation, and with deep divisions among Britain’s governing elite, Canning might have struggled. But fate intervened, and on 8 August, he died of tuberculosis at Chiswick House in West London, where his great Whig political adversary Charles James Fox had died twenty years before.

The Prime Ministers’ lives have been constantly in danger throughout history, with Truss under enhanced police protection from the moment it became evident that she was the front runner to succeed Johnson in August 2022. Any number of individuals or groups might want to assassinate the Prime Minister, fired by personal grudges, mental instability or terrorist ideals. The wonder is that only one assassin succeeded in Britain compared to four in the United States, when Spencer Perceval (1809–12) was fatally shot in the lobby of the House of Commons.

So general election defeats, illnesses, sudden death or assassination cannot explain the departure of Truss. But two final explanations for truncated premierships take us closer to an answer. First, some Prime Ministers have had personalities simply unsuited to the demands of the job. Viscount Goderich was one, third shortest-serving Prime Minister at just 144 days. As Frederick John Robinson, he’d been a reasonably successful Cabinet minister, and latterly Chancellor in the 1820s. But in the top job, he proved indecisive, thin-skinned, self-pitying and incapable of generating respect. George IV soon tired of him, supposedly describing him as ‘a damned, snivelling, blubbering, blockhead’. Goderich resigned finally in January 1828, and remains the only Prime Minister in history never to have been in office while Parliament was sitting, which then recessed between the summer and mid-January.

Was Liz Truss’s personality fatally ill-suited to being Prime Minister? Was she incapable of learning how to do the job? We shall probe in the chapters that follow whether she was wanting in either character or aptitude (or both).

Finally, there are the Prime Ministers who fall through abject failure of their central policy. Neville Chamberlain, a high-quality and proven administrator and politician, had long waited to take the reins from Stanley Baldwin, when he did so in May 1937. He anticipated a long stay, expecting to win the general election due in 1940 and to spend the following years executing his plans for economic and social reform. He and his wife intended to modernize the living accommodation in No. 10 too and make Chequers, the country home in Buckinghamshire the Prime Minister has used since 1921, into a more welcoming residence for visitors. But Chamberlain fatally misread Hitler, believing that he could coax him into being reasonable. When Hitler’s actions from late 1938 onwards showed him to be anything but, the ground fell away from under Chamberlain’s feet.

Anthony Eden similarly had progressive plans, and had to wait a long time to step up to the top. He had been Churchill’s anointed successor since the Second World War but the old leader only finally retired in April 1955. Eden went on, unlike Truss, to win his own mandate in the 1955 general election. But Eden became obsessed with Gamal Abdel Nasser, the President of Egypt, after his nationalization of the Suez Canal in July 1956.

In October 1956, Eden chose military intervention, and sent British forces to seize the canal and destroy Nasser. High among Eden’s follies was his deliberate decision to conceal from President Eisenhower and the Americans his secret British, French and Israeli plan to regain the canal. When the troops landed in November, the attack was roundly condemned in the UN General Assembly, Soviet Premier Nikita Khruschev threatened to send soldiers to defend Egypt, and President Eisenhower put pressure on the International Monetary Fund to deny Britain support. In the face of such a uniformly hostile response, Eden promptly declared the military operation over. The U-turn alienated political allies who had told Eden to tough it out. Churchill remarked cuttingly, ‘I would never have dared; and if I had dared, I would certainly never have dared stop.’10

One can only wonder how far Eden’s illness and medication were responsible for his wild and capricious decision-making. As he told Cabinet on 9 January 1957, ‘It is now nearly four years since I had a series of bad abdominal operations which left me with a largely artificial inside… During these last five months… I have been obliged to increase the drugs considerably and also increase the stimulants necessary to counteract the drugs’.11 Former Foreign Secretary and medical doctor Lord Owen speculates that he was taking mind-altering drugs daily during the crisis, including barbiturates, amphetamines and a drug called Drinamyl.12 The stated reason for Eden’s resignation after one year and 279 days, the fourteenth shortest period, was his ill health. But it was the collapse of his central policy that made his continuation in office impossible.

How far was Liz Truss’s collapse due to the failure of her central economic policy, and the subsequent U-turn in the face of international financial pressure? Was there indeed an establishment plot to bring her down? In 1924, many Labour supporters believed that the establishment had publicized a clearly fake document purporting to be from Grigory Zinoviev, head of the Communist International in Moscow, to British communists urging them to engage in subversive activities that would be helped by a Labour government. Publication of this alleged letter in the Daily Mail four days before the general election of 1924 was for many years believed to have played a significant part in Labour losing that election, meaning that its first Prime Minister, Ramsay MacDonald, was in office for less than a year (a mere 288 days). An independent report conducted by the Foreign Office in 1999 found that any attempt by the establishment, including the intelligence services, to bring down the Labour government was ‘unsubstantiated’ by the documentation, and ‘inherently unlikely’.13

Truss and some of her more ardent supporters believe that a similar establishment, or ‘deep state’, plot was responsible for bringing her down. She told the American Conservative Political Action Conference in 2024 that they had to ‘understand how deep the vested interests of the establishment are’ and ‘how hard they will fight and how unfairly they will fight in order to get their way’.14 She herself blamed Sir Tom Scholar, the permanent secretary at the Treasury, whom she and Chancellor Kwasi Kwarteng sacked on their first day in power, for encouraging the International Monetary Fund in its damning assessment of the Mini-Budget, resulting in a rush to dump UK government bonds, and the collapse in confidence of the markets. The finger of blame is pointed also at the Treasury and the Bank of England, not least for failing to alert her to the behaviour of pension funds. The Office for Budget Responsibility is also accused of undermining the economic policies. As she wrote in her book Ten Years to Save the West, ‘the Treasury establishment and the Bank of England were not on my side’.15 Was this the ‘woke’ establishment getting revenge against Truss and her right-wing ilk for bringing about Brexit? It is not just those in the political arena who believe there is truth in the accusation: journalist Robert Peston produced a podcast series in early 2024 in which he argued that the Bank of England and the Treasury were in part responsible for her fall.16 Others see the sinister hand of the supporters of Rishi Sunak, including Michael Gove, Dominic Cummings and a shadowy Tory adviser Dougie Smith, who has been linked to other plots, all intriguing against Truss from day one. Some believe that hostile Conservative MPs alerted their friends in the City of London to sell bonds to undermine the Mini-Budget. We assess whether there is reason for this belief.

Such claims are far from fanciful. When Thatcher became Prime Minister in May 1979, she too was deeply suspicious of the establishment, believing it to be against her breed of free-market economics and wish to slim down the state. Thatcher provides a constant counterpoint to Truss throughout the book. The two Prime Ministers had similarities that were not superficial: both women, from lower middle-class provincial backgrounds, passionate believers in private enterprise and British patriotism. It was a comparison Truss went out of her way to encourage – with photographs and costumes styled on those of the Iron Lady. But one went on to become one of the most formidable Prime Ministers in British history; the other, the opposite. How did that happen? Each of the ten chapters that follow focuses on one of the possible explanations for Truss’s failure, recognizing that, as with any catastrophe, the explanation will be multi-causal. At the end of the book, we reach a conclusion about the most telling reasons why she fell, and whether her bold plan for Britain might ever have succeeded.

Writing Truss at 10

A historian is only as good as their sources. Aside from two detailed tomes that cover the premiership, and Liz Truss’s own volume, other books covering her time at No. 10 have yet to appear. This means that I have had to rely on primary sources, a mixture of in-person interviews providing some 80 per cent of the book’s content, a further 15 per cent from contemporary documents including WhatsApp messages, and 5 per cent from contemporary commentary in the media.

Almost all senior Cabinet ministers, Downing Street aides and key figures from across Whitehall and beyond were interviewed for the book, some up to seven times. Verbatim records were made of all the 120 interviews (normally I conduct many more, but this was a short premiership). Many of the interviewees provided supplementary documentary evidence. To try to make the book feel as lifelike as possible – premierships happen in speech far more than in written documents – I have included numerous conversations constructed either from contemporary records or remembered by those present in the room. As always with contemporary history, so much of primary importance is never written down – the conversations, moods, messages and memories that will decreasingly find their way into the archives. All on-the-record quotations have been checked with those who provided them, and the book has been read over in multiple drafts by many researchers and insiders, as with other books in this Prime Minister series, to check for accuracy and completeness.

This book was always going to be about more than just one Prime Minister. It is also a meditation on power, and on the office of Prime Minister, and how and why incumbents, specifically this one, fail to understand either of them. It is also a practical manual on how not to be Prime Minister.

Rule Number One: Come to office with loyal MPs and a secure majority. With Hugh on 5 September hearing that she has been elected by a majority of members in the country (though Sunak had won more MPs’ support in the first round)

1

SECURE THE POWER BASE

7 July–5 September 2022

‘The response to her was tepid. We all noticed; it didn’t feel right.’

So said a Conservative MP recollecting the atmosphere among fellow MPs the first time that Liz Truss addressed them as Prime Minister. It was Tuesday 6 September 2022. Her premiership was just hours old and the omens were not good.

‘When David Cameron came to speak to us after making the deal to form the Coalition government in 2010, the MPs cheered ecstatically,’ recalled another MP. ‘They did so again when Boris Johnson first appeared before us after winning the December 2019 general election. Even when Theresa May first met us after seeing our majority wiped out in the 2017 general election, there was far more enthusiasm than there was for Liz Truss. She must’ve felt it.’

Not since 1945 had an incoming Conservative leader been greeted with such little excitement by their MPs. Indeed, it is doubtful if any new Conservative PM since 1832 had ever had such a sceptical reception. What had happened?

‘Many Conservative MPs never accepted the result of the leadership election,’ explained the MP. ‘They refused to accept that Rishi Sunak had lost. The campaign to unseat Truss started the very day her election was announced.’

Not all expected Liz Truss to emerge as the successor to Boris Johnson as Prime Minister. Not even she herself. Many Tory MPs and a majority of party members in the country never wanted him to go. Yet, in the two months between Johnson announcing his resignation on 7 July, and the announcement of her victory in the leadership competition on 5 September, Truss prevailed. In the process, her premiership was holed below the waterline before it even left the harbour.

Deciding to Run: 7–12 July

‘Come back immediately. The atmosphere is worse even than when we last spoke. The mood in the Conservative Party is beyond recovery.’ Cabinet minister and Truss loyalist Simon Clarke texted these words to her at 8 a.m. on Thursday 7 July, just hours before Johnson announced his resignation. Most inconveniently, Truss was 7,000 miles away in Indonesia for a G20 meeting in her capacity as Foreign Secretary. In the intense tropical heat, she was in a cold funk. The story began thirty-six hours earlier. Health Secretary Sajid Javid and Chancellor Rishi Sunak had resigned within minutes of each other on Tuesday 5 July, sparking speculation that Johnson would be gone within days. Should Truss leave London at all for her imminent trip while her leadership rivals were making hay? But she was mindful of the damage it could do to her cause if she was seen to be abandoning her duty while Johnson was still trying to resurrect his premiership. So she left – as planned – with a small team on the government’s sleek Airbus A321, putting in a stopover at Dubai to refuel. She spoke to Nick Catsaras, her Foreign Office principal private secretary, when the plane touched down in the Gulf, still in two minds about whether to continue further east. Conscious of the positive publicity of her high-profile summit in Bali with Russian Foreign Affairs Minister Sergey Lavrov, given her strong stance on the war in Ukraine, she was torn between duty and the possibility of the premiership.

Tim Barrow, the Foreign Office political director accompanying her on the trip, counselled pressing on too, as did her husband, Hugh O’Leary. ‘She always listened carefully and respected [Hugh’s] advice,’ said an aide. But her close trio of young special advisers, Adam Jones, Jamie Hope and Sophie Jarvis, thought differently after reading the runes in London. For years, these three had loyally served Truss, and it was partly due to their hard work that she was even in contention in the first place. Fraught conversations followed with her team and supporters. She was also talking to her closest ministerial ally, Work and Pensions Secretary Thérèse Coffey, and to her potential rival, Defence Secretary Ben Wallace, who said she should stay. ‘She was very careful not to say she was standing, but that she was merely “checking in” with friendly MPs to see how they were feeling,’ said aide Sarah Ludlow, accompanying her on the trip.

The exhausted party arrived in Bali in the early hours of Thursday morning where Truss held meetings with the foreign ministers of Indonesia and Australia. All the time, news was coming in from London, where Johnson’s premiership was visibly disintegrating by the hour. Truss was tortured by her predicament. Part of her had wanted Johnson to remain. She saw him as a pretty useless Prime Minister, above all in not pushing for the Brexit dividends, but in her heart she didn’t feel nearly ready to be PM. ‘Are you sure I’m really good enough?’ she said to one aide, looking for reassurance rather than an honest opinion. The other part of her was absolutely desperate for him to go, while playing it cool on the surface: ‘I’ll go for it only when Boris actually resigns,’ she stressed by phone to the trio back in London. But the news that he was leaving tipped the balance. ‘Liz, wake the f**k up and get back here,’ said Adam Jones, the senior of the three. She needed no encouragement, and barked out brusque instructions for her ministerial plane to ‘refuel for London’.1 She had only been on the ground in Bali for a few hours.

She would need a campaign manager if she was to prevail. In a strong field she was far from being the front runner. Her first call was to the man who had been the presiding maestro over Johnson’s 2019 general election victory, now working for the Conservative Party. ‘I want you to manage my campaign,’ she said to Isaac Levido before the plane left the tarmac in Indonesia. ‘I’m sorry. I can’t do it for you. My contract with the Conservative Party wouldn’t allow me,’ he told her. To some of her aides this was an ominous sign that the very best didn’t want to be associated with her. So she went for Ruth Porter, who had first worked for her as a special adviser in August 2014. Her aides pushed back, wondering whether Porter’s experience was suitable. But Truss was adamant. She rated her very highly for her loyalty and capability. Porter promptly left the private sector to head up the campaign.

The plane touched down late on Friday 8 July and she was driven back to her home in Greenwich. Her leadership campaign was nonexistent: no money, website, publicity material, office base or lists of potential supporters. This was ground zero. Her nascent team worked at Truss’s kitchen table. The star recruit was Jason Stein, a brilliant and mercurial communications aide who had worked on-and-off with Truss since 2017 and who had resigned as Prince Andrew’s PR guru shortly before the infamous Newsnight interview with Emily Maitlis in 2019. A video announcing Truss’s candidacy was filmed in her garden once it had been cleared of weeds and building debris.2

Where was her natural supporter base? Bridges had been burnt with the Remain wing after she emphatically renounced her vote in the EU referendum in her quest to become Brexit Queen. So she reached out for support to right-wing politicians and ardent Brexiteers Iain Duncan Smith, Bill Cash and John Redwood, as well as to financier and Brexiteer Jon Moynihan. ‘If you’re going to run, I’ll help you with the right ideological position,’ he told her. He became her campaign’s energetic Treasurer and, when she needed money, her fundraiser. Well-liked Thérèse Coffey, Truss’s oldest political friend, was tasked to corral MPs. Below them and Stein, Hope specialized on policy, Jones on communications and Jarvis on wooing supporters, at which she was adept. Truss once remarked to her that ‘MPs like you. They don’t like me. That’s why I need you.’3 Reuben Solomon, formerly of Conservative Campaign Headquarters (CCHQ), worked on digital communications, and Sarah Ludlow completed the band, having joined several months before from PR company Portland Communications. Within days, Truss had a team.

On Monday 11 July, she announced her platform: promoting growth and cutting taxes. From the outset she committed herself to reversing the rise in National Insurance that Sunak had announced as Chancellor in March 2022 and scrapping plans to increase corporation tax.4 She had her policies. She even had a slogan: ‘Trusted to Deliver’. Next up, she secured a base in Westminster’s Lord North Street (named after the PM ‘who lost America’) owned by Tory supporter Lord Greville Howard. The Moynihan money-till began ringing loudly. She had cash. She had momentum. She was in business.

But she wasn’t yet in the race. According to the rules announced that Monday by Graham Brady, Chair of the 1922 Committee of Tory backbenchers, candidates had to acquire the backing of twenty MPs by the following day if they were to make it to the first of the two leadership rounds. Eleven candidates announced their intention to run. ‘I was holding the pen. It was a real struggle whether we’d get those twenty signatures committed by 4 p.m. on Tuesday,’ said loyalist MP Ranil Jayawardena, ‘but we did it by 2 p.m.’ Coffey was her proposer, right-winger Simon Clarke seconder, ‘the idea being to have two Cabinet ministers from different ends of the party’.5 Prominent among the twenty was her near neighbour in Greenwich, Kwasi Kwarteng, already earmarked for Chancellor, and James Cleverly, who had worked with her closely as junior minister at the Foreign Office.

Round 1: The MPs (12–20 July)

Tuesday 12 July brought big news: the public endorsement of Truss by two of Johnson’s staunchest supporters, Culture Secretary Nadine Dorries and Minister of State for Brexit Opportunities Jacob Rees-Mogg. Here was evidence that Johnson himself, destined to be a massive influence on the campaign, might favour her among the candidates. Better still, and in contravention of the protocol that only the PM speaks from the street outside No. 10, they made their announcement with the famous black door in the background. ‘Boris had spoken through his two most loyal lieutenants.’ However, there was a caveat, a crucial one: ‘It was less a positive vote of confidence in her than a move to thwart Rishi,’ said a Johnson insider.

‘Liz was always opposed to Rishi’s higher taxes. [She expounds] proper Conservatism… she’s got the character to lead the party and the nation,’ intoned Rees-Mogg to waiting journalists. ‘I have sat with Liz in Cabinet now for some time. [I’m] very aware that she’s probably a stronger Brexiteer than both of us,’ he added.6 Not figures of great political gravitas maybe, but gold dust all the same because of the imprimatur of Johnson. The suggestion was that Truss would be the best candidate to carry the Brexit flag forward.

That mattered because the leadership field was rich with more authentic Brexiteer candidates. A ConservativeHome survey of Tory members published as the contest opened put Penny Mordaunt top on 20 per cent, Kemi Badenoch on 19 per cent, Rishi Sunak on 12 per cent and Suella Braverman on 10 per cent. Fifth and last, and the only one known not to have voted for Brexit, was Liz Truss, scraping in at nearly 10 per cent.7 The onetime matinee idol on the ConservativeHome website, who had unsettled Johnson so much he’d sent her to the wasteland of the Foreign Office in September 2021, had sunk to the floor. She had work to do.

Three candidates were eliminated before the first hurdle for not reaching the magic number of twenty MP backers. They included two heavyweights: former Chancellor Sajid Javid and long-term Cabinet survivor Grant Shapps, as well as the backbencher Rehman Chishti. Eight made the cut.