3,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Next Chapter

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

This small Texas town will never be the same again.

When the good people of Cranston learn a hometown boy has been killed in Iraq, they begin preparing a memorial for their fallen hero.

But nobody thinks to ask the boy’s father, Joe Morton, if such a service is wanted - or welcome. Crippled by grief, Joe goes along with the plans of the townsfolk until he can bear no more. On the Fourth of July, he tells them just how he feels.

Joe's act of independence has unexpected consequences. The residents - and Joe himself - are completely unprepared for what happens next: change and the outside world come to Cranston.

First runner-up, 2010 Pirate's Alley Faulkner Society Gold Medal

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Ähnliche

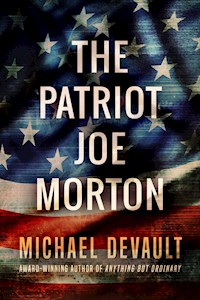

The Patriot Joe Morton

Michael DeVault

Copyright (C) 2010 Michael DeVault

Layout design and Copyright (C) 2019 by Next Chapter

Published 2019 by Next Chapter

Cover art by Cover Mint

This book is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents are the product of the author's imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual events, locales, or persons, living or dead, is purely coincidental.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without the author's permission.

patriot (pā'trē–ət)

n. one who loves, supports and defends one's country

The American Heritage Dictionary

September: Casey Morton

Chapter One

Joe Morton was never considered a stable man. He had never lashed out, was not taken to fighting in bars. In fact, no one could remember his ever going into a bar. But he wasn't what the good people of Cranston considered normal. If you were to put any of the twelve hundred or so citizens of the small east Texas town on the spot, you would arrive at some variation of “Joe simply doesn't do things the way people expect.”

He didn't own a tractor, opting instead to pay the Carmichael boy a few dollars to run the bush hog over the eighty acres he had inherited from his great aunt. Every Sunday, he occupied the same pew at Cranston First Baptist and, like the rest of the men, refrained from speaking his amens, though he would nod at the appropriate moments. And every morning, Joe arrived for breakfast at the Truck Stop Café around nine, where from table seven, the booth against the window, he read The Cranston Sun and drank three cups of coffee before shuffling off to start his day–though what he did each day, no one could say for sure.

There were a lot of things no one could say for sure about Joe Morton. That was a problem for the people who lived in the town he had called home for the last forty years. So the good people of Cranston had always approached him with a measure of caution, a caution of which for the most part, they were never quite sure of the cause. They kept their concerns about Joe's tenuous mental state in check with a healthy dose of “just don't think about it” until, one Tuesday in September, the leather strip of bells went clattering against the glass door of the Truck Stop Café.

In those days, strangers so rarely came into the Truck Stop Café that Doris Greely, the morning waitress, didn't immediately know how she should react. She exchanged a quick glance with Harlan, her lone customer, before finally rising to greet the young man. For his part, the stranger stood in the doorway, patiently knocking a spot of dust from his blue suit and arranging a matching blue tie neatly beneath his lapels. It wasn't until the staccato beats of his shoes resonated against the tile that Doris looked down and recognized the patent leather shoes of an Air Force man.

“Well howdy, son,” she said. “You must be up from the base?”

“Yes, ma'am. You wouldn't happen to know how to get to Macomb Road, would you?” He removed a small notebook from his inside breast pocket and double-checked the address, adding a self-affirming nod. “Yes. Macomb Road.”

Later, Harlan and Doris would remember this event in excruciating detail. They would recall the manner in which the officer tilted his head just so to one side. Harlan would recite how, sitting with his back against the wall–as he always did–the small cross on the man's chaplain insignia reflected into Harlan's eyes. Doris would recount the softness of his hands and the peculiar accent she couldn't quite place, perhaps upstate Ohio, as it was one of the many places she had never visited. They would repeat these and a hundred other trivial details to the news crews, to reporters, and to tourists so eager to devour any detail of the story. At that moment though, Harlan and Doris had only one concern. It was Harlan who gave it voice.

“What you want with Joe Morton?”

“I'm sorry, sir. It's a personal matter,” the officer replied.

Harlan waved a dismissive hand at him. “Well, son, we ain't got much time for personal matters around here.”

Doris shot Harlan a biting look before turning back to the officer. “It's about his boy, ain't it?”

When the officer hesitated, Doris rested a hand on his shoulder. “It's okay, son. You don't have to tell us.”

Harlan's head dropped, and his shoulders slumped. After a moment or two in silence, he lifted his head. “Head out the highway and take a left at the old feed mill–”

Doris interrupted. “Let me just draw you a map, son.”

A few minutes later, she watched him cross the parking lot of the Truck Stop Café to the waiting Ford Taurus, take his seat behind the wheel, and momentarily confer with two other uniformed men in the car before driving out Highway 7. By the time she returned to the corner booth, Harlan was staring silently into his lap. For the next ten minutes or so, while the Air Force chaplain made his way out to Macomb Road, they alone would carry the burden of knowing the war had claimed one of Cranston's own.

While Harlan plucked imaginary lint from the black felt of his cowboy hat, Doris compulsively checked her makeup and tried to smooth her red hair tighter into the bun at the back of her head. She was about to start polishing the flatware when she heard Harlan's cup rattle against his saucer and she looked up.

“How about a refill, Doll?”

She shook her head. “Pot's gone cold. Besides, I think it's about time you headed home. Something tells me this is going to be a long week.”

Chapter Two

For twenty years, whenever Doris arrived to open the Truck Stop Café, she had been greeted by the same empty parking lot. The rows of big rigs that used to idle in the parking lot belonged to a time before Doris had gone to work for Jimmy, before Harlan's daddy had succeeded in getting the Interstate to forego a route through Cranston, which had forced the closure of the Cranston Truck Stop and left as the only reminders an empty slab that used to be the station and a spotless, gleaming diner.

Yet on the morning after they learned of Casey Morton's death, Doris pulled into the parking lot shortly before dawn and was dismayed to find Harlan's black Chevy Silverado idling near the front door. It was the kind of development that made Doris question her decision to forego a domestic life in exchange for independence. For a moment, she considered returning home and calling in sick, but Harlan had already seen her headlights and was making his way towards the door.

Despite her misgivings about Harlan, his tenacity impressed her. That distinctive limp, the one lingering disability of a twenty-foot fall from an oil platform, rarely slowed him down.

She checked her makeup in the rearview mirror and took an extra few seconds to brush a stubborn tangle out of her hair. In the glow of the car, her hair still looked soft and red. None of the gray at her temples was visible, and in that place lit only by the dome light, it was easy to pretend she had not aged much in the last few years.

Harlan was sitting on the bench near the door when she finally made it to the front of the café. He was staring out across the pastures towards the horizon, to where a band of low clouds glinted with the first golden hints of dawn. Doris held the door open and gestured for him to enter.

“Coffee won't make itself, Harlan.”

He didn't budge. “That's okay. Think I'll sit out here for a few and watch the sunrise. Looks to be pretty, don't it?”

“Suit yourself,” she said, but she lingered. Instead of going inside, she let the glass door close and sat down beside him. “I don't think I've ever seen you here this early.”

“We've got a lot of plans to make, now, don't we?”

She eyed him, at once curious and confused. “What plans?”

“The Morton boy. We got a hero coming home. That requires planning.”

Doris momentarily considered arguing with him. She didn't know Joe Morton any better than anyone else in Cranston, but she knew he was a private man who might not take to the attention a Harlan Cotton production would bring to his quiet existence. But Doris knew stubborn, and she had long ago given up confronting futility. Harlan decreed the boy's memorial service would be a town event. That was the way it was going to be. No amount of persuasion would change that. So Doris did the only thing she could to combat her dread of the day that was about to unfold. She sat in silence and watched the sun rise.

They were still sitting there when Ted and Margie Bartley pulled in.

“Morning Doris,” they said in unison.

“Y'all aren't usually here on a weekday.”

“Thought we'd change it up a bit,” Margie said. “I've been telling Ted for ages we're getting predictable.”

Doris just nodded, aware of the real reason they were there on a Wednesday. She smoothed her apron flat as she stood and opened the door. While Ted and Margie settled into their booth, she slipped into the back room, past Jimmy in the kitchen and into the cubby behind the walk-in freezer. She fished through her apron until she found the hard edges of her cell phone, removed it, and dialed Carly Machen.

Doris counted the rings, judging by each additional ring just how deeply unconscious her night waitress was. Finally, after seven rings, a groggy Carly picked up the phone.

“Hello?” came the feeble voice from the other end.

“Carly, I need you,” Doris said. She didn't bother masking the pleading in her voice and knew what it would take to get a twenty-two year old out of bed before eight a.m. “I'll take your shift tonight and tomorrow night. And we'll split tips sixty-forty.”

“What? What's going on?”

“Your Uncle Harlan's called the whole damned town to the café to plan the Morton boy's memorial service,” Doris said without thinking. It took her a moment to place Carly's silence into the proper perspective of four years of a schoolgirl romance followed by a ring and a promise of marriage after what had promised to be a short deployment in a short war. Though they both worked at the Truck Stop Café, the two were on different shifts. So Doris knew Carly only peripherally and, in any other situation, neglecting to remember the ins and outs of a coworker's love life would be at best a regrettable oversight. Now, though, Doris felt an emptiness that opened into the pit of her stomach. In all her haste, Doris had forgotten that Carly was Casey Morton's fiancé.

“Oh baby doll! I am so sorry,” Doris said.

She could hear the unmistakable, muffled sounds of the girl crying into her pillow. Doris pictured Carly's jet black locks spilling over her face, her mouth open and dried tears streaking her cheeks. Doris wished she had remembered Carly and Casey before picking up the phone. She wished she could be there, in Carly's bedroom, cradling the girl through her grief. But more than anything, Doris wished she could bring Casey Morton back for Carly.

When at last she heard her coworker uncup her hand from the receiver, Doris tried again to comfort her. “Carly baby, I am so sorry. I just didn't think–”

“It's okay,” Carly said. “I'll be there in a few minutes.”

“No, you stay home. You don't have to come in. As a matter of fact, take the week off. I'll cover your–”

“No, I said I'll be there in a few minutes,” Carly replied. Doris knew from the girl's insistent, almost defiant tone that arguing with her would be as fruitless as arguing with Harlan.

“Besides,” Carly added, a tone of finality in her voice, “maybe I don't need to be alone right now. So I'll see you in twenty minutes.”

The phone went dead before Doris could reply. She dropped it back into her apron pocket, leaned absently against the side of the walk-in, and succeeded in fighting back her own wave of tears. When she returned to the dining room, the number of customers had grown exponentially. In Doris's absence, Margie had donned an apron and was filling coffee cups.

“Hope you don't mind the help,” she said with a smile.

Doris didn't protest, opting instead to listen in on the state of affairs. There would be a small memorial service at the town square. Harlan had already arranged to bring the band from Cranston High to provide the appropriate musical atmosphere. Johnston Metalworks would cut and install an additional half dozen flagpoles to line the sidewalk opposite the half dozen they placed at the nine-eleven commemoration a few years back.

“It'll make for nice effect leading up to the band stand, you know–from the south approach,” Greg Johnston said, glancing around the room to gauge everyone's approval.

Doris saw Carly's Nissan pull into the parking lot and decided now was the time to speak up. “Guys, we need to table this discussion for a few minutes. Carly's here.”

Doris immediately regretted saying anything, as every person in the Truck Stop Café fell silent and turned to watch the door. About halfway through the parking lot, Carly stopped, hesitated for a moment as she saw two dozen sets of eyes staring at her. She walked through the diner, to the register, and picked up a ticket book before turning to face them.

“Relax, everyone. I'm fine, really. I'm fine.”

Doris slid an arm around Carly, gently squeezing her waist. She felt the light brush of fingertips before Carly pulled away and started directly for Harlan's table. Doris couldn't help but smile to herself at the girl's strength and, in that space of a few seconds, Doris knew futility found no home in Carly Machen.

Somewhere over the course of serving breakfast, Doris caught Carly's infectious resilience and found the fortitude to carry through the morning. Moving about the restaurant with a coffee pot, Doris picked up quiet snippets of recollections of this poem or that song. When Margie suggested her church choir could sing “The Battle Hymn of the Republic,” she smiled. She dropped off another plate of bacon on Harlan's table and listened for a moment about a twenty-one gun salute–which Harlan assured the men the Air Force would provide.

Each time a sense of unease began to creep up her spine, she returned behind the counter and polished flatware for a moment or two. It was a simple act and one she often retreated to in anxious moments. The action of the soft cloth gliding over the smooth bowl of a spoon soothed her nerves. By the time the first lunch patrons arrived, Doris had lost the need to polish silverware altogether and deemed her initial apprehension misplaced. The people of Cranston understood more about Joe Morton than she thought. This memorial would be a celebration of Casey Morton's life and service, sober and appropriate.

While Doris was clearing away the last of the breakfast dishes and Carly was busy putting out the lunch menus, the Franklin twins arrived with their own offering for the service.

“We're volunteering our horses and the wagon. You know, to pull the coffin from the square to the cemetery,” the first Franklin brother said.

Harlan nodded thoughtfully at the suggestion, rubbed his chin, and smiled. “That's mighty charitable of you, Jerry.”

Ted Bartley cleared his throat. “If we're going to have a processional, someone needs to get Shep to sign off on it.”

“Don't you worry about Shep,” Harlan said. “I'll handle the mayor.”

He polished off the last dregs of coffee in his cup and smiled. “Well, boys, looks like we're going to have a parade.”

Chapter Three

Despite the creeping tingles in his left foot, Harlan was doing his best not to move. The vinyl cushion belched every time he adjusted his weight, and he was determined to spare himself the embarrassment of the young nurse's assuming his stomach was the culprit.

She smiled at him as she fastened the blood pressure cuff around his arm. “How was the trip down, Mr. Cotton?”

“Same as always. Long and boring,” he said.

The truth was, though, Harlan had been thankful for the drive. The two hours from Cranston to Waco always gave him time to clear his head and order his thoughts. He had awakened before dawn, his mind filled with a jumble of minutiae for the Morton boy's service. By the time he arrived at the V.A., he had successfully ordered all the problems into manageable logistical categories.

The nurse removed the cuff and jotted the measurements onto the chart. He tried to read the numbers as she recorded them, but gave up. “So how'd I do?”

“Great,” she said with a smile. “As always. One-twenty over eighty. Doctor will be in in a few.”

She left the folder on the table and closed the door behind her. Harlan shifted his weight and sent a rush of blood to his aching foot. Someone had hung a poster outlining the human skeletal system on the back of the door, the kind of poster Harlan assumed medical types hung in order to make the room appear more medical. He had been to the V.A. so many times in the past year and a half, he began keeping track of which room he had been in by the posters. He saw similar maps of the nervous system, the vascular system and the digestive system, and not once did any medical person refer to the posters for explanation. The one time such illustrations would have been constructive, the doctor deferred instead to a bad photocopy to show him where the prostate was and the functions it provided.

The door opened and the doctor entered in silence. He reviewed Harlan's chart and jotted a few notes before looking up and removing his glasses. “Good morning, Mr. Cotton. How's life in Cranston?”

“More of the same, I suppose,” he said. The doctor rested the stethoscope against his chest and he inhaled deeply.

“So any problems?”

“No, not really. We have a funeral day after tomorrow for a boy killed in Iraq, but that's–”

“I meant with your health?”

Harlan nodded. “No, nothing to speak of.”

The doctor made a few more notes in the chart and flipped the page. As he read in silence, Harlan tried to read some significance in the man's expression but saw none. At last, the doctor closed the chart.

“So. All your labs look good. Normal. Blood pressure's solid. Other than the prostate, you're a picture of health. Especially for a man in his late sixties.”

“And the cancer?”

“Well, like I told you. You'll always have cancer, unless we remove the prostate–”

“I don't want that.”

“Right. So we're going to continue brachytherapy every year and checkups every six months. And we'll keep watch on your P.S.A. levels for any changes. I'd also like to rescan your prostate on your next visit, just to make sure.”

Harlan stood and began pulling on his trousers. “You got anything else I need to know?”

The doctor shook his head. “No, Harlan. But I see your billing address listed as a post office box? Still haven't told your wife?”

Harlan shook his head. “Ain't planning to, neither.”

With a sigh, the doctor signed the chart. “I wish you didn't think you have to go through this alone, Harlan. It can be helpful to have someone to discuss things with, someone who knows what you're going through.”

“That's what I got you for.”

“That's not what I meant. I mean–”

“I know what you mean, and, no thank you. She don't know. She don't need to know.”

The doctor shrugged. “Fine. It's your marriage. You're retired, Colonel. I can't order you to tell her.”

“That's right, you can't. And even if I wasn't retired, Lieutenant Colonel–”

The doctor laughed. “Okay. Okay. You win. Just think about it? And make sure to come in for your labs in a few weeks. Don't skip it this time.”

Harlan shook the doctor's hand. “Doc, it's not that I don't think she can handle it or anything. It's just–”

“I understand. I don't agree and I don't like it, but I do understand.” The doctor tossed Harlan's chart onto the table and leaned back against the wall as his patient buttoned his shirt. “So tell me about this kid. The one who died?”

“Dad's from Cranston. He was dating Carly. My niece? The kid, not the dad. She's real busted up about it, but she's holding it together. Whole town's getting together for the memorial service at the end of the week.”

The doctor smiled. “That's nice.”

“It's going to be big. You should come down and see it.”

“Nah, I've seen enough military funerals in my day. I'd just as soon not. But give my respects to his father.”

Harlan nodded. He knew he wouldn't mention the visit to Joe, and the doctor didn't expect him to. It was just the kind of thing you said to a man.

They said their goodbyes and the doctor left Harlan with a handful of prescription slips for the pharmacy. When Harlan smiled at the nurse as he passed, she winked. As the doors to the V.A. closed behind him, Harlan felt a sense of relief. Another visit down, another good report. He climbed into his Silverado and, turning the key in the ignition, he paused and said a quick prayer of thanks.

“Amen,” he said aloud and fired up the truck.

Chapter Four

Joe didn't return to the Truck Stop Café for three days and, for this, Doris was thankful. She understood he needed time to heal. Plus, she was unsure he would have been able to handle the onslaught of people that Harlan had assembled in those first couple of mornings. By the third day, though, talk had died down and was, for the most part, turning away from Casey Morton's memorial and to discussions of hunting lease rates for the fall and which road the aldermen would resurface first when the Legislature finally signed off on the state highway bill.

Life was slowly getting back to normal and Doris moved from table to table, topping off coffee cups and chatting with the truckers and, when they weren't alone, their companions. So busy was she that Doris could almost forget the war, Casey's homecoming and even the emptiness at table seven. Despite a full house, Joe's table had remained vacant throughout the mornings, as if the customers were anticipating his arrival any moment.

Doris had to admit she, too, was antsy. Dropping off an order at Ted and Margie's booth, she decided she would slip out to Macomb Road after her shift ended and take him a nice ham, or at least a banana crème pie. Those plans were dashed midway through breakfast when Joe turned up. And not much about him had changed.

At first, no one seemed to notice him taking his seat in the booth against the window. Harlan and the boys continued debating whether ducks or deer would be where the money was this season. Ted and Margie didn't bother looking up from their coffee and newspapers. Even Doris hadn't heard the clatter of doorbells when he came in. She had no idea how long he had been waiting when she finally noticed him sitting there, hands folded on the table, coffee cup turned upright on the saucer.

She scrambled over with the pot. “Didn't hear you come in, Joe. You want breakfast?”

He shrugged, then nodded.

“I'll fix you up, baby.”

Doris rushed away from the table, scribbling an order for two eggs over easy, bacon, sausage and toast. As an afterthought, she jotted “on the house” across the bottom of the ticket before ringing the bell in the window. Jimmy took the ticket and hung it on the first clip.

“Good to see him back,” he said.

When Doris returned to table seven a few minutes later with a second cup of coffee, she couldn't get to the table. Harlan and the boys were crammed into the booth, pressing in on Joe as Harlan outlined the town's plans for Casey's funeral.

“And then we'll turn at Fourth Street before heading up to Memorial Park for the concert and flag raising,” Harlan said. “So what do you think?”

Joe was again staring across the parking lot, wordless and unmoving. Harlan batted him on the shoulder.

“Joe, you alright, buddy?”

Joe's nod was anything but committal. “Sure, Harlan. Sounds real nice. But you really shouldn't go through all the hassle.”

“Nonsense. The boy's a hero.” Harlan took a long draw off his coffee cup and winced. “A bona fide hero, he is.”

Margie leaned forward and rested her hand on his shoulder. “You got any family coming into town?”

Joe shrugged. “My wife's sister, maybe. But ain't heard from her yet. She was traveling.”

“Well, when she gets to town, you just let us know. We've got a room at the motel waiting for her. No charge, understand?”

Joe protested. “I don't want to put you out. This all just sounds like a whole lot of trouble.”

“Trouble? It wouldn't be no trouble, Joe,” Margie said. “Ain't like we don't have rooms going spare every night.”

“That's right,” Ted added. “It's the least we can do.”

Doris shoved past Margie and Ted and up to the table, pausing long enough to shoot a disapproving glance at Harlan. She slammed the saucer down so hard coffee sloshed out of the cup and onto the table. Elbowing Harlan aside, she placed a roll of silverware at Joe's right hand.

“Here you go, Joe. And I'm making a fresh pot.”

“Thanks, Doris,” he said without looking up from the deep pool of the cup.

Several seconds of uncomfortable silence descended over the table. The men showed no sign of budging of their own accord and Doris wasn't about to leave them hovering while Joe ate. With a clap, she began waving them out of the booth.

“Y'all leave Joe alone. He's just wanting peace and quiet, don't you think? Shoo!”

The morning cadre shuffled away mumbling. Doris tried to laugh it off, but it wasn't working. “I'm sorry about that, Joe. They don't mean harm.”

He forced a smile. “I know, Doris. They just want to help, I guess.”

She paused, with the full intent of providing him the solace she knew he so desperately needed, but when their eyes met, Doris realized she didn't know what she was going to say.

“I…Joe, I'm–”

“It's okay, Doris. You think I wasn't ready for this when Casey signed up?”