18,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: The Crowood Press

- Kategorie: Wissenschaft und neue Technologien

- Sprache: Englisch

This book is one of a popular and exciting series that seeks to tell the story of some of Britain's most beautiful landscapes. Written with the general reader - the walker, the lover of the countryside - firmly in mind, these pages open the door to a fascinating story of ancient oceans, deltas, mineralization and tundra landscapes. Over millions of years the rocks that now form the spectacular terrains of the White Peak and the Dark Peak were laid down on the floors of tropical seas and deformed by plate tectonics before being shaped by streams and rivers. The white limestone was fretted into its own distinctive landscape above hidden cave systems; then generations of miners and farmers modified and contributed to the landscapes we see today. With the help of photographs that are largely his own, geologist Tony Waltham tells the remarkable story of the Peak District, explaining just how the landscapes of limestone plateau, grit moors and river valleys came to look as they do. Including suggestions for walks and places to visit in order to appreciate the best of the National Park's landforms, this accessible and readable book opens up an amazing new perspective for anyone who enjoys this varied and beautiful area.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 285

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Ähnliche

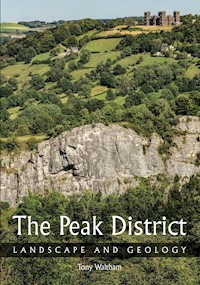

The Peak District

LANDSCAPE AND GEOLOGY

Ladybower Reservoir and the Dark Peak, seen from Bamford Edge.

The Peak District

LANDSCAPE AND GEOLOGY

Tony Waltham

First published in 2021 byThe Crowood Press LtdRamsbury, MarlboroughWiltshire SN8 2HR

www.crowood.com

This e-book first published in 2021

© Tony Waltham 2021

All rights reserved. This e-book is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 78500 875 7

Acknowledgements

Maps in these pages have been abstracted and compiled from numerous sources, before being redrawn and embellished by the author. Due credit belongs to members of the British Geological Survey for their source information and mapping, and also to the many cavers who made the original underground surveys.

A huge thank you and great credit go to the late Paul Deakin, mine surveyor, caver and photographer who lived in the Peak District and left a massive legacy of excellent photographs of mines and caves all over Britain; Paul’s images are on pages 63TR, 82B, 86T, 87T, B, 88, 89T, 90, 91, 92, 100B, 102, 105, 108, 110L, 124, 144B, 152, 153 and 154. The author is also grateful to friends who supplied photographs: Rob Eavis (pp. 17, 78, 104, 119B, 121), Anthony Raithby (pp. 50, 51, 93, 141, 143T, 156), Phil Wolstenholme (p. 101), Brendan Marris (p. 82T), Karl Barton (p. 114), Noel Worley (p. 112T) and Robbie Shone (p. 145L); also to Scarthin Books (p. 66B), and for image backgrounds to Google Earth (pp. 53B, 85L). All other photographs are by the author.

Thank you also to Dave Lowe, Peter Worsley, Noel Worley and Don Cameron who reviewed draft texts of some chapters; to Judy Rigby for providing fossils from her collection; and to the late Trevor Ford, whose knowledge of the Peak District was both massive and infectious.

The book is dedicated to the author’s wife Jan, whose boundless support made everything possible, and who appears as scale in many of the photographs.

Front cover: Reef limestone forming the great white cliff of High Tor, seen from Masson Hill across the Derwent Gorge, with Riber Castle on the grit escarpment beyond.

Cover design by Maggie Mellett

Contents

1 White Peak and Dark Peak

Starting with the Rocks

2 White Peak Limestone

3 Dark Peak Grit

4 Derbyshire Dome

Creating the Landscape

5 Shaping the Peak District

6 Through the Ice Ages

7 Limestone Country

8 Underground

9 Moorland and Sheepwalk

Imprint of Mankind

10 Mineral Riches

11 Stone for Industry

12 Villages of Stone

13 Dams and Reservoirs

14 Landscape to Enjoy

Further Reading

Index

CHAPTER 1

White Peak and Dark Peak

Limestone gorges, swathes of green pasture, villages of stone, grit edges and peat moors: these are the features that distinguish the Peak District. Each could claim to be iconic, but it is the combination of them all that makes the real splendour and the glorious landscapes of this southern section of the Pennine Hills.

The hills at Castleton are a microcosm of Peak District landscapes.

The limestone of Treak Cliff is in the foreground with the Winnats gorge cut in behind it, all parts of the White Peak.

Within the Dark Peak, Mam Tor and its landslide are just beyond, then Edale lies in front of the grit moors of Kinder Scout that stand high in the distance.

Even within the national park, there are two very distinct halves to the Peak District, each with its own style of landscape. On the outcrop of the limestone, the White Peak forms most of the southern half of the park. It is a land of farming, with some fields of crops but many more of fescue grass pasture for grazing sheep, to such an extent that in summer it should perhaps be called the Green Peak. In contrast, the Dark Peak is on the gritstone country that forms the smaller northern half of the park and also extends into southern arms on each side of the White Peak. It is a land with little farming value, relished only by the grouse that nest in the heather. With peat bogs and the dark Juncus reed grasses, it looks more like a Brown Peak except during the seasonal bloom of purple heather.

The high ground of the Pennines and the Peak District, between their adjacent lowlands, with the boundary of the Peak District National Park and the margin of the limestone outcrop that defines the White Peak.

These two landscapes, each on its own rock type, have both been carved out by a million or more years of erosion, and that has been largely by rainwater, streams and rivers. Ice Age glaciers did leave their mark across the Peak District, but mainly in rather subtle ways, and practically all the landforms, whether of White Peak limestone or Dark Peak gritstone, were fashioned by water erosion.

Outline geology of the Peak District, with the National Park boundary shown in black.

The Peak District through geological time. Most landscape features were developed during the last million years, within the Quaternary, after all the rocks had been created more than 300 million years ago. Quaternary events are shown on page 57, and Carboniferous events are shown on page 34.

An early phase of the geological history saw a great equatorial lagoon surrounded by reefs atop a structural block known as the Derbyshire Platform, wherein the White Peak limestones were created. These were then buried by huge deltas in which were deposited the Dark Peak gritstones. Next came the uplift and folding of the Derbyshire Dome, followed by erosion that stripped the gritstones away to expose the limestones and form the White Peak. But the limestones were rather different when they reappeared because they had been shot through by mineral deposits during their time of deep burial.

It was thus geology that guided a major factor in the last stage of the evolution of the Peak District landscapes – the stage that bears the imprint of mankind. Few landscapes are now without the farming, villages and towns that add to a purely natural world, but the White Peak also has a fascinating heritage from a mining industry that is now almost, but not quite, in the past.

So the Peak District landscapes are not entirely natural – unless human beings are accepted as a component of the natural world. Perhaps they should be, even if they are unusual in their ability to impose their own features in a time-span much shorter than those of most geological processes. Quarries, factories and roads may be regarded as negative factors in a landscape, but mankind’s impact can be beneficial. The grit edges of the Dark Peak are steep and dramatic because they are actually old quarry faces, and the beautiful open vistas of grassland in the White Peak are free of trees because they are grazed by sheep that have been brought to the area by farmers.

Mankind has also introduced some delightful quirks in the names of features within the Peak District landscapes. The numerous wells, which feature in the annual well dressings, are not wells; to anyone but a local, they are natural springs, but they were important sources of good, clean water in the past. Then there are the hills that are called lows. Their name originates from hlaw, which is Anglo-Saxon for a mound or burial mound or even a rounded hill. So there is a hill north of Monyash with the confusing name of High Low.

Black Rock’s grit crags overlook Dene Quarry in the underlying limestone near Cromford.

It is this combination of the natural world and mankind’s imprint that makes the Peak District so attractive and well worthy of its national park status. Then, behind all the landscapes and each landform, there is a defining influence within the geology. This has evolved through hundreds of millions of years, first with formation of the rocks, and then much later with their erosion and denudation. The development story of the Peak District is now broadly established, but there are still some unknowns. What was the source of the water that carved the Winnats gorge? When did glacier ice last fill Edale? Are there more mineral deposits still to be found? Where did the Duke’s Red Marble come from? These questions simply add interest to a good theme, and there is a fascinating story within the landscape and geology of the Peak District.

CHAPTER 2

White Peak Limestone

Limestone defines the White Peak. Formally known as the Peak Limestone Group, but often just referred to as the Carboniferous Limestone, this great thickness of strong limestone is of Early Carboniferous age. The clean rock is pale grey in colour, but much of it weathers to a white patina. It has determined both the landscape and the economic development of the southern half of the Peak District National Park. Favoured by today’s quarrymen in search of strong aggregate stone and by yesteryear’s miners who sought the lead from its veins, it also provides the home ground for cavers and climbers; and it has been eroded to form some of the most spectacular scenery in the Pennines.

The sequence of limestones exposed within the White Peak reaches to more than 800 metres thick, and about the same thickness again lies unseen beneath any outcrops, where it is known from just a few deep boreholes. Even the full 800 metres of exposed limestone cannot be seen at any one place because the topography of the Peak District does not reach such heights. However, the limestone has a regional dip towards the east, so the older beds are at outcrop mainly in the west, whereas the younger beds are mainly exposed in sequence towards the east.

The limestone succession seen at outcrop is divided into four main units, which can barely be distinguished by anyone without local experience. The Bee Low Limestones are perhaps the archetypal White Peak material, because they are generally homogeneous, largely occur in thick beds and are the palest of grey colours. Above them, the Monsal Dale Limestones are rather more variable, with beds that are either pale grey or rather darker grey and are either thick-bedded or thin-bedded. Even darker and typically thinly bedded are the Eyam Limestones and the Woo Dale Limestones, at top and bottom of the exposed sequence respectively.

Typical bedded Monsal Dale Limestones exposed in an old roadside quarry north of Monyash.

Main units within the sequence of limestones that lie at outcrop across the Peak District, with their various stratigraphical terms, together with the most extensive of the lavas and also the black marble and chert beds that occur in the upper part of the Monsal Dale Limestone around Bakewell.

A conspicuous feature on geological maps of the White Peak is the wide outcrop of the Monsal Dale Limestones on the eastern side, with only a narrow and discontinuous outcrop to match on the western side between the Bee Low Limestones and the Millstone Grit cover. This is due to a combination of factors, with steeper dips on the western flank of the Pennine Anticline alongside local faulting, some local unconformities, reefs that mark the limit of the lagoonal limestones and also some westward thinning of the Monsal Dale beds. Then the Eyam Limestones are missing in the west, as they were only formed in the shallow eastern basins. Such are the lateral variations in the geology, but endless uniformity should never be expected in the natural world.

Outcrops of the main units within the limestone sequence in the White Peak. The Eyam and Monsal Dale limestones are shown together. The only lava marked is the Upper Miller’s Dale where it lies between the Bee Low and Monsal Dale limestones, both of which are dolomitized west of Matlock.

Features of the paleogeography of the shelf seas of Dinantian times, with a thick yellow line that traces the outer edge of outcrop of the limestones now forming the White Peak. Not all the volcanoes and reefs were active or alive at the same time, as these features were spread over more than ten million years.

Bedded limestones exposed in the quarry at the Hope Cement Works, with thinner bedding and darker horizons within the Monsal Dale Limestones, lying above the more thickly bedded Bee Low Limestones, which lack the dark horizons.

Along with the lower beds seen nowhere at outcrop, all these units constitute the Peak Limestone Group that was formed as marine sediment between about 345 and 330 million years ago. In terms of international stratigraphy, these limestones of the White Peak correspond roughly to Lower Carboniferous, Mississippian, Visean or Upper Dinantian parts of the succession. Dinantian is perhaps the most familiar term, though it derives its name from the crags overlooking the town of Dinant on the banks of the River Meuse in Belgium.

Lagoon limestones

The White Peak is essentially the area of limestone outcrop at the crest of the Derbyshire Dome. This is a chunk of ground that has been relatively high through long stretches of geological time. It was a seabed high beneath the early Carboniferous seas, when it was a shelf covered by shallow water and surrounded by basins and gulfs of deep water. During subsequent earth movements it was raised within the core of the Pennine Anticline, and it is high ground in the present landscape.

The edge of the Derbyshire Platform in early Carboniferous times, with low islands atop the line of reefs fringing the shallow lagoon where lime sediments are accumulating on the left; deep water appears as deep blue on the right, beyond the reefs. This comparable situation is along the margin of the Bahamas Banks.

It was the depths of the Carboniferous seabeds that determined the nature of the limestones. Back in those times, the White Peak looked rather like the Bahamas Banks of today, with their cluster of shallow lagoons and low islands together surrounded by fringing reefs with their outer margins dropping steeply into deep water. The limestones originated in the lagoons, where calcareous sediments were accumulating steadily, largely in the form of shell debris from the abundant marine life. Britain was close to the Equator at the time, and animal life thrived in the warm sea water. Creatures of both free-swimming and bottom-dwelling habits nearly all had skeletons or shells made of calcite, which they extracted from the lime-saturated sea water. When they eventually died, their skeletal remains added to those that accumulated for millions of years on the lagoon floors.

The reefs of strong limestone that form Chrome Hill and Parkhouse Hill in Upper Dovedale, with the fields below on shales and the dark escarpment of Longnor Sandstone beyond and left of the reefs.

Limestone is thus composed largely of shell debris, some as intact fossils, but most as fragments, along with some of the calcium carbonate deposited directly from the sea water. When such a pile of calcareous sediment is buried and compressed beneath younger sediments, it recrystallizes into a mosaic of calcite that is then known as limestone.

Bedded limestones across the great expanse of the White Peak were formed in the shallow waters of an extensive lagoon, or a series of lagoons. These developed on a broad submarine shelf, surrounded by deep water that ensured no land-derived sand or mud sediment could be carried in to contaminate the carbonate deposition. Nevertheless, the limestones are divided into beds by their bedding planes, which are inherently weak.

Some bedding planes were created merely by changes in the depositional process. Others were formed when earth movements or sea-level changes left parts of the lagoon floor temporarily above water level. The exposed sediment then developed a hard crust, perhaps embellished with a little plant debris or wind-blown dust, and when back beneath sea level would create a bedding plane. Some of these bedding planes are lumpy and irregular because the bed beneath was eroded or pitted by dissolution prior to re-burial and deposition of the next bed of limestone.

Yet more of the bedding planes exist because they contain layers of clay, sandwiched between two beds of pure limestone. The thicker of these clay beds, up to more than a metre at some sites, are known as wayboards, a miners’ term for the step that was commonly created between two beds of limestone. High potassium contents in these wayboard clays indicate that they consist largely of volcanic ash, and are companions to the lavas within the White Peak limestones. At the thin end of the scale, clay partings only a millimetre thick are seen as bedding planes; however, they too are likely to be thin layers of volcanic ash blown in from small or distant eruptions, which were frequent and worldwide at that time.

Whether clean bedding planes, clay partings or thick wayboards, these features have had enormous influence on many aspects of the Peak District. They are weaknesses in the limestone, which are picked out by erosion perhaps to form steps in the landscape, or form slip surface for landslides and rockfalls where they are inclined within dipping limestones. Underground, they guided, deflected or impounded rising mineral-bearing fluids, so that they constrained the shape and extent of the orebodies subsequently exploited by miners. Similarly they influenced flows and patterns of underground drainage through the limestone, as can be seen in the morphology of the caves that have been developed by the acidic groundwaters.

Just as on the modern Bahamas Banks, local conditions varied considerably across the complex of lagoons that were the White Peak in Carboniferous times, and so the limestones vary in detail. One rock type is known as Ashford Black Marble. This is not a true marble that has been recrystallized during metamorphic processes, but is a strong, compact limestone; it is known in the stone trade as a marble because it can be polished to a smooth surface. It was formed in the deeper waters of the Ashford Basin, west of Bakewell, which was a local feature of the shelf sea during the later stages of limestone deposition. At times, bottom waters in the basin stagnated and became depleted in oxygen, so organic carbon was preserved and became the tiny proportion of bituminous material that darkens the rock.

The same basin was also host to the Rosewood Marble, another limestone that can be polished for ornamental use. This one is notable for its fine laminations, with variable amounts of clay and iron minerals producing its various brown colours. At some sites, its laminations are uniform, but at other localities they are contorted due to slumping of the wet sediment before it was lithified.

Chert is yet another feature of the limestones formed in the small and shallow basins of the Bakewell area. Despite its black colour, chert is almost pure silica that is derived from a small proportion of marine life-forms, including sponges and minute radiolaria, which have siliceous skeletons. At first forming just a small proportion of the dominantly calcareous sediment on the seabed, the silica was re-dissolved during diagenesis and concentrated into isolated nodules and some almost-continuous beds. Within the multiple processes of diagenesis, whereby sediment is turned into rock, dissolution and precipitation of both carbonate and silica are critically dependent upon the acidity of the interstitial pore-water. Consequently, either pure chert or pure limestone can form separately where and when the right chemical conditions prevail.

Blocks of grey chert with their bedding vertical forming capstones on a wall in Stoney Middleton.

One more variation within the White Peak bedrock is dolomite. This is essentially a limestone, but with part of its calcite replaced by the mineral dolomite. The mineral of that name is a carbonate similar to calcite except that half of its calcium is replaced by magnesium. Dolomite rock can be a primary deposit, as in the lowest beds of the White Peak limestone that are not exposed at the surface. Or it can be a secondary rock, formed where magnesium-rich waters invade a calcitic limestone. This appears to be the case with the belt of dolomites and dolomitized limestones extending towards the northwest from Wirksworth; these were probably altered by magnesium-rich brines descending from a Permian seabed. Because dolomite is slightly less soluble than limestone, it tends to form resistant crags within a karst landscape, as at Harboro’ Rocks near Brassington.

Reef limestones

The rim of a marine platform has the combination of shallow water on the shelf with large waves sweeping in from deeper waters. Where the waves break against the shallows, the turbulent and foaming water is aerated and oxygenated, making it a prime site for marine life. In particular, many corals grow only in water less than about 60 metres deep and gain benefits from the oxygenation, so coral reefs are formed and grow progressively to massive dimensions. Ultimately these create reef limestones, which are typically strong and structureless, consisting of a chaotic but solid mass of corals, algae and lime mud, together with shell debris from the myriad animals that had lived on, in and around the reef.

Strong reef limestones tend to form residual hills within the modern landscape, and because the extent of the White Peak roughly matches that of the Derbyshire Platform in the Carboniferous sea, these hills are the distinctive landforms around the margins of the limestone outcrop. Thorpe Cloud in Lower Dovedale, Chrome Hill in Upper Dovedale, Treak Cliff at Castleton and High Tor at Matlock Bath are the finest of the White Peak reefs. The first three are apron reefs, with lower ramparts of debris draped over the slopes down into deeper water. Corals, algae and bryozoans contributed to making a stable framework in parts of the reef, but the side slopes were ramps of fine-grained debris of broken shells and coral.

Treak Cliff reveals some of the structure of an apron reef. Its core is fairly structureless reef limestone that grades towards the southwest into the back-reef bedded limestones of the lagoon. In contrast, its front face, towards the east, is a fore-reef apron of shell debris and broken blocks of reef that cascaded down into deep water where the Hope Valley now lies. Known as the Boulder Bed, this ramp of debris continued to accumulate after the end of the Dinantian by wave erosion of the reef, which was by then largely dead due to the onslaught of muddy water into the marine basin. The broken limestone then gained significance as the prime host of the Blue John mineral deposits that now lie within the face of Treak Cliff.

The limestone reef of Treak Cliff overlooking Castleton, with the plateau of lagoonal limestones forming the skyline. The reef is scored by the Winnats gorge left of centre, and by the smaller Odin Gorge on the right.

A variation of the Boulder Bed contains numerous rolled and rounded fragments of the large fossil brachiopod Gigantoproductus; originally misnamed as a ‘Beach Bed’, this was formed where shell debris rolled down a channel cut into the front to the reef. The channel was then filled with younger sediments and, much later, re-excavated to form the Winnats gorge, where the shell beds are now exposed near the Speedwell Cavern car park.

The great lens of unbedded limestone was a patch reef in a lagoon, but is now exposed in the great cliff of High Tor that overlooks Matlock Bath.

High Tor is the White Peak’s fourth classic reef with its great lens of structureless limestone between bedded limestones on both sides, all revealed in profile in the cliffs of the Matlock Gorge. Unlike the apron reefs that overlooked deep water, High Tor is one of many patch reefs that developed within the interior of the White Peak lagoon. These are better described as carbonate mud-mounds, which formed as local accumulations of lime mud and fine shell debris on the lagoon floor; the material was held in place and bound together by algal filaments and bryozoan mats, most of which are now unrecognizable in the recrystallized limestone.

These mud-mound reefs now form lenses of massive, structureless limestone, but most are barely conspicuous within the landscape because they are surrounded by equally strong bedded limestone. They do not compare with Chrome Hill and Parkhouse Hill, at the head of Dovedale, which were higher and steeper apron reefs buried by soft shale and then exhumed; they are classic examples of reef knolls, which are those hills of today that have their shapes defined largely by their ancestral marine reefs.

Fossils in the limestone

Though it forms the White Peak, most of the limestone comes in various shades of grey, before its outcrops are whitened by a thin patina created by its weathering. The grey colouring is due largely to tiny amounts of included organic carbon derived from the soft bodies of myriad marine animals. It is hardly surprising that there is some carbon left behind when practically the entire rock is formed of the shells and shell debris that were the hard parts of those same creatures. Despite being made largely of fossils, or fossil fragments, the limestone is barely welcoming to fossil hunters because most of it is devoid of collectible fossils.

Cross-sections of corals can be seen in many White Peak rock faces, but intact fossils are not easily extracted from the solid limestone. Colonial corals, notably Syringopora, and solitary rugose corals are both widespread in the Peak limestone. Best known of the latter is Dibunophyllum, which could grow to the size of a small banana. A spectacular bed packed with broken and complete corals of this species is exposed around the foot of the Hob’s House landslip in Monsal Dale, where the fossils have been silicified so that they now stand out from their more easily weathered limestone matrix.

Cross-section of a cluster of the rugose corals now named Siphonodendron junceum, and previously known as Lithostrotion.

Common inhabitants of the clear Carboniferous seas were the bottom-dwelling brachiopods, with their two thick shells hinged to allow opening and feeding (though totally unrelated to the bivalve molluscs that include clams and scallops). Fossil shells of Gigantoproductus are typically the size of a clenched fist and are the largest brachiopods that ever lived. Some can be found in shell beds that formed where the animals were crowded together on lagoon floors. One thick shell bed has its silicified fossils forming a distinctive knobbly roof along cave passages in Carlswark Cavern, near Stoney Middleton.

The roof of one of the main passages in Carlswark Cavern, at Stoney Middleton, is a bed crowded with fossils of Gigantoproductus with their calcite shells having been repaced by silica, so that they stand clear where the limestone matrix has been removed by dissolution during development of the cave.

A specimen of the brachiopod Productus productus, with its domed convex shell on the left and its smaller concave shell on the right.

Various species of Spirifer, a brachiopod with a long projecting hinge-line, are also common in the reef limestones, as are the little Rhynchonella brachiopods. The strong shell of the latter, only sugar cube in size, weathered out of the reef and were easily picked up on the slopes of Treak Cliff before many years of collecting rendered them rather scarce.

A bed of limestone formed of crinoid fragments large and small. This slab forms the doorstep of the Bulls Head pub in Monyash, and likely came from the old Ricklow Quarry in nearby Lathkill Dale.

Perhaps best known of the White Peak fossils are the crinoids that grew as forests on the lagoon floors. There were forests of them, but they were not trees. These were animals related to sea urchins that each stood high on a single skeletal column resembling the stem of a plant. The animal’s body shell, known as the calyx, was easily crushed and broken when it died, but the cylindrical calcite columns, and similar but thinner arms, are abundant in some beds. They belong to the genus Actinocrinus. Along with individual segments known as ossicles, each the size and shape of a tap washer, these create very distinctive shapes in the polished faces of slabs of crinoidal limestone. Beds of this material occur at various horizons within the White Peak limestones, and have long been quarried for use as ornamental stone. The old Ricklow Quarry in Lathkill Dale yielded stone with notably large crinoids, and some beds of Hopton Wood Stone, quarried around Middleton, were unusually attractive with their dark matrix enclosing white crinoids. It was one of many fossiliferous limestones that provided ornamental stone in the past, but now nearly all the White Peak’s quarried limestone is crushed to produce aggregate, cement or lime.

Volcanic interludes

Within the thick sequence of limestones that form the White Peak, numerous lavas and ash beds tell of volcanic activity around and beneath the equatorial seas and lagoons of early Carboniferous times. Hardly anywhere do these rocks form features in the landscape, because the strong limestone and the hard volcanic lavas are equally resistant to erosion. But a scatter of small scars, road cuttings and old quarries in darker rock do make some of the basaltic lavas traceable on the surface, and many more were recorded by the lead miners of the past. Though barely a feature of the modern landscape, the ancient volcanic rocks were hugely important to the miners, because the valued minerals are so often found in the limestone just beneath beds of lava or volcanic ash.

Volcanic rocks that are known in the limestone sequence of the White Peak. The marked extent of lavas below ground is largely interpreted from old mine records and borehole logs, and probably extends farther. Marked volcanic vents are those that are known; others could exist within the areas of lava below ground. The lavas are not all contemporary, but were formed during a number of eruptive phases. Volcanic ashes that form wayboards are not shown, as they can be found across almost the entire area.

Toadstones and wayboards

Peak District lavas are commonly known as toadstones. The term could have come from the mottled greenish brown colour of the weathered lava, or might have been a variation on todstein, which was a German miners’ term for dead rock, meaning that it contained no mineral.

Many of the Carboniferous volcanoes produced basaltic magma that formed extensive lava flows, a few metres or a few tens of metres thick, either on the shallow seabed or on low-lying land perhaps self-created by an accumulation of lava. There are few places within the White Peak where structures indicating submarine or subaerial eruption can be recognized within the lava, and the most common features of the thicker lavas are some degree of spheroidal weathering. This is where water in the rock’s fractures hastened its decay especially on the edges and corners of angular blocks, which therefore became rounded, largely while within the zone of intense weathering close to ground level.

Basaltic Lower Miller’s Dale Lava at the foot of the limestone crag of Ravenstor, near Litton Mill.

Some of the lavas are amygdaloidal, meaning that they solidified from the magma while it still contained gas bubbles that were subsequently filled with minerals. Because most of these gas-deposited minerals are white, the spotted appearance of amygdaloidal lava is quite distinctive. One toadstone, seen only in mine workings south of Eyam, consists entirely of hyaloclastite. This rock consists largely of fragments of glassy basalt that were created when a lava was chilled and broken up by steam during a gassy underwater eruption; it appears that this volcano never grew above sea level, and its submarine outpourings were never stable enough to form solid underwater lava flows.

Among the most extensive and conspicuous lavas in the White Peak, the Upper and Lower Miller’s Dale Lavas and the Upper and Lower Matlock Lavas are the best known, each found at outcrop around the localities after which they are named. The southern extremity of the Upper Miller’s Dale Lava is seen at outcrop south of Chelmorton, which is about four kilometres from its probable vent at Calton Hill, and again on the Monsal Trail at the same distance to the northeast. Beyond the latter site, the horizon of the lava can be traced eastwards as a thin bed of volcanic ash that probably emanated from the same eruption. There are many more lavas interbedded within the Peak limestones; more than thirty have been recognized, each at its own stratigraphic level, but all are of limited lateral extent; basaltic lavas rarely flow for more than 5 or 10 kilometres before they solidify.

Besides extruding lava, some of the known Carboniferous basaltic volcanoes of the White Peak became more gassy and produced airborne debris, which never accumulated in the quantities to build great cones like those of explosive andesitic volcanoes. This material is described as pyroclastic (meaning fire-fragmental) and is known as tuff, which includes the fine-grained air-fall material that is also known as volcanic ash. Air-fall ash was produced from vents in and around the Carboniferous Peak District and was spread by the winds over very large areas, so that it now appears within the limestone sequence as the clay beds known locally as wayboards.