8,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: John Wiley & Sons

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

A woman’s life is different. This is clear when a stranger’s catcall makes her feel targeted in the street. When politicians make off-the-cuff sexist remarks. When media commentators wade in with their condemnation of free, unrestricted abortion. When a father is praised to the skies for attending parents’ evening while the mother’s attendance is taken for granted. When they fire her because she’s pregnant. When they dismiss her medical symptoms as anxiety. To counter sexism today, we need to learn the art of self-defence. Today, feminism is more alive and more necessary than ever because discrimination against women has become more subtle and difficult to detect, yet it retains its paralysing power. With combative energy and acerbic wit, Bel Olid explains the key concepts of the current feminist struggle in a smart, radical and often counterintuitive way.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 135

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Ähnliche

CONTENTS

Cover

Table of Contents

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

To Be or Not to Be

Machine Guns

Not All Men

Raped Bodies, Rapable Bodies

Misfits

Don’t Wash Your Dirty Linen in Public

Love Doesn’t Kill

Together We’ll Take Back the Night

#Onsónlesdones

The School of Life

We Don’t Want to Wear the Trousers

Being Nothing to Be Everything

Feminist Mini-lexicon: 25 Words for Naming Reality

Sources

End User License Agreement

Guide

Cover

Table of Contents

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Begin Reading

Feminist Mini-lexicon: 25 Words for Naming Reality

Sources

End User License Agreement

Pages

iii

iv

v

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

72

73

74

75

76

77

79

80

81

82

83

84

85

86

87

88

89

91

92

93

94

95

96

97

98

99

100

101

102

103

104

105

106

107

108

109

110

111

113

114

115

116

117

118

119

120

121

123

124

125

126

127

128

129

130

131

132

133

134

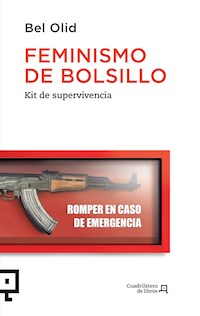

The Pocket Guide to Feminism

A Survival Kit

Bel Olid

Translated from Catalan by Laura McGloughlin

polity

Originally published in Catalan as Feminisme de butxaca by Angle Editorial © Bel Olid, 2017. Translation rights arranged by Asterisc Agents

This English edition © Polity Press, 2024

The translation of this work has been supported by the Institut Ramon Llull

Polity Press65 Bridge StreetCambridge CB2 1UR, UK

Polity Press111 River StreetHoboken, NJ 07030, USA

All rights reserved. Except for the quotation of short passages for the purpose of criticism and review, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher.

ISBN-13: 978-1-5095-6474-3

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Library of Congress Control Number: 2024939853

The publisher has used its best endeavours to ensure that the URLs for external websites referred to in this book are correct and active at the time of going to press. However, the publisher has no responsibility for the websites and can make no guarantee that a site will remain live or that the content is or will remain appropriate.

Every effort has been made to trace all copyright holders, but if any have been overlooked the publisher will be pleased to include any necessary credits in any subsequent reprint or edition.

For further information on Polity, visit our website: politybooks.com

Dedication

To Aijun, Ada, Blai and Gael. I hope you can feel free.

And to all of you in the struggle, who fill my world with joy.

To Be or Not to Be

It’s a boy. It’s a girl.

Looking at the screen I can only see a beating heart, something resembling arms, life in black and white inside my womb. But it’s a boy. Or a girl.

We don’t yet know if they’ll like painting, if they’ll prefer spaghetti to croquettes, what colour eyes they’ll have, whether their hair will be blond or black. We don’t know their way of smiling or crying or losing their temper or living. But we’re told ‘it’s a boy’ or ‘it’s a girl’ and suddenly the world is divided into two possibilities and that’s that – pink and blue, arts and sciences, power and beauty.

It’s so automatic a process that many experiments have been conducted about a baby’s supposed gender and the attitude it provokes. In one of the studies, for example, some babies were dressed in pink and others in blue, then they were shown to various people. These people described the babies dressed in pink as ‘pretty, sweet, delicate, small’; those in blue as ‘strong, intelligent, stubborn, big’. The babies’ clothes were switched: those in pink were dressed in blue and vice versa. With its clothing changed, the same baby’s characteristics magically changed too. Those who were ‘small’ suddenly became ‘big’; those who were ‘strong’ suddenly became ‘delicate’.

And then, much uneasiness. Once it’s confirmed that the world will react differently to this unknown person depending on whether I name them Ben or Brenda, how can I make space for them to be whoever they might want to be? How do I make space for him to dress in pink if he wants, or for her to play football if it’s what she likes? Or, even more complicated, how do I make space for them to discover whether they are a she, a he or a they? The answer is more worrying than the question: I can’t. Socialization will come along, life will come along, and however much we insist on having clothes of all colours at home, they’ll go to school and learn the box to which they have been assigned and the punishments that await them if they leave it. It’ll be their job to work out whether it’s worth going against the flow or whether they prefer to adjust to it and go unnoticed.

We’ve been so conditioned by culture that right now it’s impossible for us to know which part of the division of biological sex comes from nature, which part is made up of characteristics ‘naturally’ shared by a sufficiently large majority of people with XX or XY chromosomes to make reasonable generalizations, and which we impose on ourselves as a society, assigning characteristics which are not innate, but forced on us by the reading of how we should be as regards our sex. Having reached this point, it’s certainly undeniable that Simone de Beauvoir was completely right when she said that one isn’t born, but rather becomes, a woman. And we can add that it’s exactly the same for men.

When we’re born (or even from the earliest ultrasound images), our external sexual organs are examined and, if there’s nothing unusual, we’re classified as a man or as a woman. It’s a boy; it’s a girl. A person’s biological sex is determined by the sex organs, chromosomes and hormones they generate. If the external sexual organs are obvious, nothing further is inspected. If the group to which they belong isn’t so clear, tests are done and everything else is studied.

Not everyone fits into the male box or the female box, which seems surprising because it’s discussed very little, despite the fact that it’s more common than we might think. There are people with XXY chromosomes; there are people with XY chromosomes who don’t secrete enough testosterone or aren’t sensitive to it (and therefore have external sexual organs resembling the majority of people with XX chromosomes); there are people with XX chromosomes who secrete more testosterone than usual (and therefore can develop certain secondary characteristics resembling those of the majority of people with XY chromosomes); and a thousand other variations. This group of people with such diverse characteristics have to fit into the man group or the woman group at all costs, because our society doesn’t allow any alternative.

Thousands of people with intersex conditions (or differences in sex development – ‘DSD’ for short) from around the world endure medical (surgical or hormonal, for example) interventions to make them externally adapt to one of the labels, long before they are able to give consent. The thinking behind this is that there’s been a ‘mistake’ in nature which needs to be corrected. But, in truth, the characteristics of intersex people don’t interfere with their health (as interventions do). They don’t have an illness that needs to be cured. Nowadays, many intersex people who have reached adulthood ask that these children’s bodies be respected and any interventions put off until they’re old enough to ask for them and give informed consent. We’d do well to listen to them.

When we’re born, we’re assigned either of the only two possible sexes. Even from a legal point of view, being classified is imperative: otherwise, in most states around the world, we can’t be added to the civil register. If it’s unclear whether it’s a boy or a girl, we have to make it up. The doctors propose something based on the results they’ve collected and the gender it seems will be easiest for the child to perform according to their biological characteristics, and the parents usually listen.

But even in unambiguous cases in which the three elements determining sex coincide, two things can happen when the person grows up: they agree with the diagnosis of being a boy or a girl (and then they’ll be cisgender) or they don’t agree and know that they’re a boy even though they’ve been told they’re a girl, or vice versa (and then they’ll be transgender). It could also happen that they don’t feel comfortable with either group and end up labelling themself as agender, queer, gender-fluid or non-binary. And then life gets complicated: we like simplifications (it’s a boy, it’s a girl) and get very nervous when someone steps out of the box. However much we state we don’t want labels, we’re more than that, it’s no use. Strangers will place us in one of the two boxes at first glance (if you have a beard, you’re a man; if you have breasts, you’re a woman; if you have both, alarm bells) and they treat us accordingly, whether we agree or not.

The box is what we call ‘gender’: the behaviours we expect of a person according to the biological sex we assume they have – that is, the rules we learn to follow according to whether we’ve been told we’re boys or girls. These rules have little to do with a person’s abilities and preferences, and are applied not only before abilities can be expressed but before they can even be discovered. We don’t give small children the chance to discover what they really like because we mercilessly apply gender restrictions that will prevent our son wearing dresses or our daughter being assertive.

You can’t go to the registry office when the person you’re carrying in your womb is born and say: ‘Look, I don’t know if it’s a boy or a girl or something else entirely; they don’t know how to talk yet and I don’t know them at all.’ And determining whether a person ‘is’ a boy or girl is not only legally, but socially, imperative. The few instances where families have decided not to publicly communicate the biological sex of their baby, in an attempt to avoid putting the pressures of gender on them and to allow the child to develop unhindered by stereotypes and prejudices, have provoked all kinds of judgment directed at the parents. Why don’t they let them ‘be normal’? How should these babies be treated? Do I refer to them as ‘him’ or ‘her’? Doesn’t calling them ‘they’ sound ridiculous?

It’s a boy. It’s a girl. I know how I need to treat them. It’s reassuring. We don’t want to abandon the available boxes, and perhaps, given how the system is structured, abandoning them isn’t reasonable, but greater flexibility between them would be very good for everyone. If I’m classified as a woman, but all that follows from this ‘being a woman’ is the possibility that in the future I might have the physical ability to become pregnant, and everything else is left open, I’ll have the freedom to discover myself. On the other hand, if my bedroom has already been painted pink and a pile of dolls bought for me before I was born, and as I start to grow I’m told ‘that’s not for girls’ when I stray from the norm, it’ll be harder to know whether I like pink because it’s pretty or because I’ve been force-fed it.

Research has shown that the favorite colours of babies younger than 1 are blue and red. Some babies prefer blue and others red, but there is no division by sex. Pink is of little interest – nor are grey and brown. However, by the age of 4, girls show an undeniable preference for pink, and boys avoid it at all costs. By then, they’ve had time to learn which group they belong to and what their colour is. Furthermore, the girls have learned to respect the codes of the colour blue, even though it’s not theirs, and the boys have learned to disparage pink.

Almost everything can be generalized in this way. The most intrepid girls quickly learn to repress themselves, and the most fearful boys to be brave. Only the people who, for whatever reason, have more difficulty in acting as is expected of them find themselves forced to seek other paths, which will never be easy. The boys with hobbies that are considered feminine, whether it is dancing or experimenting with hair and make-up, have to endure taunts and insults even now – just like the girls with hobbies considered masculine.

In this book, the words ‘men’ and ‘women’ don’t refer to a person’s biological sex, not even their gender expression, because we know there are many more than two possibilities. We’re talking about the set of expectations society has for people classified as a man or a woman, and the rules applied to them. When we say ‘Women shoulder the greater part of the duties in the traditional family’, we mean ‘Society expects the people categorized as women to shoulder the greater part of duties in the traditional family.’ When we say ‘Men earn 24 per cent more than women’, we mean ‘The average salary of people categorized as men is 24 per cent higher than that of the people categorized as women.’

We know that there are infinite different ways of living: there are men who earn less than some women, there are women more aggressive than some men, and we know that there are people who don’t consider themselves man or woman and don’t know where they sit. But we also know that there are privileges enjoyed and discriminations suffered depending on which label falls to you, and that label is placed on you without you asking. This is what we’re talking about, with generalizations as necessary as they are realistic.

It’s a boy. It’s a girl. The impossibility of being you, whoever you may be, and being treated as a person, full stop, whoever you may be. It’s a boy; it’s a girl. When they’d really like to be just a heart beating in all the colours that exist.

Machine Guns

My fantasy is a machine gun.

When I’m on the street and a stranger shouts something at me: a machine gun.

When the typical politician makes a typically sexist remark: a machine gun.

When a newspaper quotes a bishop who wonders how women expect not to be raped if they ask for free, unrestricted abortion: a machine gun.

When a father attending parents’ evening is praised to the skies, but the mother attending is taken for granted: a machine gun.

When they fire you because you’re pregnant: a machine gun.