Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Luath Press

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

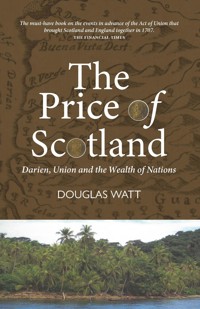

The Price of Scotland covers a well-known episode in Scottish history, the ill-fated Darien Scheme. It recounts for the first time in almost forty years, the history of the Company of Scotland, looking at previously unexamined evidence and considering the failure in light of the Company's financial records. Douglas Watt offers the reader a new way of looking at this key moment in history, from the attempt to raise capital in London in 1695 through to the shareholder bail-out as part of the Treaty of Union in 1707. With the tercentenary of the Union in May 2007, The Price of Scotland provides a timely reassessment of this national disaster. REVIEWS Douglas Watt has brought an economist's eye and poet's sensibility in the Price of Scotland... to show definitively... that over-ambition and mismanagement, rather than English mendacity, doomed Scotland's imperial ambitions. - THE OBSERVER The Price of Scotland treats Darien as a financial mania. - THE FINANCIAL TIMES Exceptionally well written, it reads like a novel. As I say - if you're not Scottish and live here - read it. If you're Scottish read it anyway. It's a very, very good book. - i-on magazine The must-have book on the events in advance of the Act of Union that brought Scotland and England together in 1707 is Douglas Watt's The Price of Scotland. It's a fantastic run-through of the "catastrophic failure" of the Darien Scheme - the creation of the Company of Scotland to establish a Central American colony. THE FINANCIAL TIMES

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 541

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2014

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

DOUGLAS WATT is an historian and historical crime writer. He was born in Edinburgh and has an ma and phd in Scottish History from Edinburgh University. He is the author of a series of historical crime novels set in late 17th century Scotland featuring investigative advocate John MacKenzie and his side-kick Davie Scougall. Douglas lives in East Lothian with his wife Julie.

Praise for The Price of Scotland

Exceptionally well written, it reads like a novel. As I say – if you’re not Scottish and live here – read it. If you’re Scottish read it anyway. It’s a very, very good book.

MATTHEW PERREN, I-ON MAGAZINE

It is this mess [the state of Scotland at the time of Union] to which Douglas Watt has brought an economist’s eye and poet’s sensibility in the Price of Scotland… to show definitively… that over-ambition and mismanagement, rather than English mendacity, doomed Scotland’s imperial ambitions.

RUARIDH NICOLL, THE OBSERVER

… a compelling and insightful contribution to our understanding of Darien.

BILL JAMIESON, THE SCOTSMAN

A fundamental re-evaluation of the Darien project… What we have here are the opinions of a historian who became a financial analyst and who has worked in the world of finance. Watt uses his background to bring to life the history and the economics of the Company of Scotland… Watt shows with devastating effectiveness the level of sheer financial mismanagement and poor and stupid strategic decisions on the part of the Company directors.

THE SCOTTISH REVIEW OF BOOKS

The Price of Scotland treats Darien as a financial mania.

BRIAN GROOM, THE FINANCIAL TIMES

Douglas Watt’s lucid account of the affairs of the Company of Scotland is a valuable contribution.

SUNDAY HERALD

A fresh assessment of the disastrous attempt to establish a trading colony in the tropical and hostile conditions of Central America.

THE HERALD

By the same author:

HISTORICAL CRIME FICTION

Death of a Chief

Testament of a Witch

Pilgrim of Slaughter

The Unnatural Death of a Jacobite

A Killing in Van Diemen’s Land

First published 2007

Reprinted 2007

This edition 2024

ISBN: 978-1-909912-91-5

The author’s right to be identified as author of this book under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 has been asserted.

Typeset in 10.5 point Sabon

© Douglas Watt 2007, 2024

Quis talia fando temperet a lachrymis? (Who in speaking of such matters could refrain from tears?)

VIRGIL

The main hazard in an affair of this nature always has been, and ever will be, of a rash, raw, giddy, and headless direction.

WILLIAM PATERSON

To Julie, Jamie, Robbie and Katie

Acknowledgements

THIS BOOK WOULD NOT have been written without the support of the Stewart Ivory Foundation, who funded a research fellowship at Edinburgh University allowing me to conduct an exhaustive examination of the financial records of the Company of Scotland. I would like to thank the trustees of the Foundation and in particular Angus Tulloch, Janet Morgan and Russell Napier for generous advice and enthusiastic encouragement.

My research has been carried out in a number of archives. Thanks are due to the staff of the Bank of England Archive, British Library, Edinburgh City Archive, Glasgow University Library, Mitchell Library, National Library of Scotland and National Archives of Scotland. I would like to thank in particular Ruth Reed of the Royal Bank of Scotland Archive and Seonaid McDonald of the Bank of Scotland Archive for providing friendly access on many occasions to the records of Scotland’s oldest financial institutions. The Duke of Buccleuch and the Earl of Annandale kindly allowed me to consult their private papers. Thanks to Sir Robert Clerk of Penicuik for permission to quote from Leo Scotiae Irritatus.

The Scottish History department of Edinburgh University has proved a very congenial environment for historical research. Thanks to colleagues there, especially Dr Alex Murdoch for guidance and support. My knowledge of the late 17th century has been greatly deepened by many informal conversations with 17th century Scottish historians Sharon Adams, Julian Goodare, Mark Jardine, Alasdair Raffe and Laura Stewart, and with students on my Darien honours course. Doug Jones very kindly provided a copy of his dissertation on Darien and popular politics and I am also indebted to Prof Femme Gaastra, Prof Charles Withers and Allan Hood for answering enquiries on a variety of topics.

Thanks to my parents for their love and support. My wife Julie has offered many helpful comments on the original manuscript. I would like to thank her and our children Jamie, Robbie and Katie for their encouragement, love and forbearance during my three year sojourn with the Company of Scotland.

Contents

Lists of Figures and Tables

List of Illustrations

Preface to 2020 edition

Preface

Introduction

CHAPTER ONE The Strange Dream of William Paterson

CHAPTER TWO Imperial Bliss

CHAPTER THREE The Company of Scotland

CHAPTER FOUR London Scots

CHAPTER FIVE Raising Capital in a Cold Climate

CHAPTER SIX Directors

CHAPTER SEVEN Mania

CHAPTER EIGHT International Roadshow

CHAPTER NINE The Talented Mr Smyth

CHAPTER TEN Assets

CHAPTER ELEVEN Cash is King

CHAPTER TWELVE Disaster in Darien

CHAPTER THIRTEEN Caledonia Now or Never

CHAPTER FOURTEEN Second Chance

CHAPTER FIFTEEN Frenzy

CHAPTER SIXTEEN Other Ventures

CHAPTER SEVENTEEN Bail-out

Postscript: The Wealth of Nations

Conclusions

Chronology

Principal Characters

Appendices

Bibliography

List of Figures

Figure 1 Monthly Subscriptions 1696

Figure 2 Bank of Scotland Total Return 1699–1719

Figure 3 Company of Scotland Net Cash 1696–1705

Figure 4 Monthly Payments from First Capital Raising 1696–1699

Figure 5 Monthly Debt Repayments by Subscribers 1696–1699

Figure 6 Capital Raisings 1696–1700

Figure 7 Company of Scotland Net Cash 1696–1705

Table 1

Ratios of shareholders to population, tax and money supply

List of Illustrations

The coat of arms of the Company of Scotland

Cash chest of the Company of Scotland

Lock mechanism on the main cash chest

A map of the Darien colony by Herman Moll

A Map of the West Indies by Moll

Letter by James Smyth, May 1697

Sir John Clerk of Penicuik

Sir Mungo Murray

The Cash Book 1696–1700

John Blackadder

The crude map of the colony from the account of Francis Borland

The last gold coins struck by the Scottish Mint

John Hamilton, Lord Belhaven

Hugh Dalrymple

John Hay, second Marquis of Tweeddale

Adam Cockburn of Ormiston

Patrick Hume, Earl of Marchmont

George MacKenzie, Earl of Cromarty

Preface to 2024 edition

THE PRICE OF SCOTLAND’S publication coincided with the tercentenary of the Union of the Parliaments between Scotland and England in 2007. The book is a financial history of the Company of Scotland, better known as the Darien Company, concerned principally with the nexus of finance and politics. It focuses on the disastrous management of the Company’s capital and the bail-out of shareholders by the English government which made Union possible in 1707.1

At the time of publication, another financial crisis was brewing. Northern Rock collapsed in the summer of 2007 and, within a year, the Bank of Scotland and Royal Bank of Scotland were on the verge of the abyss. This was the biggest crisis in Scottish finance since Darien.

The response to the global financial crash included quantitative easing (QE), the creation of money by central banks on an unprecedented scale, as a way of saving the financial system. QE boosted the wealth of those who owned assets like property and shares, while the majority faced years of austerity and wage stagnation.

The political impact of the global financial crisis is still being felt. In England, it no doubt contributed to the anger underpinning the Brexit victory in the EU referendum of 2016. In Scotland, it intensified frustration with the Union. The SNP formed a minority administration following Scottish Parliamentary elections in 2007, but gained a majority in 2011, paving the way for the holding of a referendum on Scottish independence in 2014. The result was much closer than the British elite had expected.

The global financial system remains vulnerable. The corona-virus pandemic of 2020–2022 resulted in massive government interventions across the global economy with a vast expansion of government debt. The stability of the British state is being undermined by high debt and inflation, and the aftershocks of Brexit. With support for Scottish independence sitting at around 50% in the opinion polls – compared to around 25% in 2007 – the union between Scotland and England appears increasingly fragile.

Against a backdrop of financial and political uncertainty, the history of the Company of Scotland is still of interest and relevance.

1 Our knowledge of the Company of Scotland in its Atlantic setting has been greatly expanded by Julie Orr’s Scotland, Darien and the Atlantic World,1698–1700.

Preface

THE ATTEMPT BY THE Company of Scotland to establish a colony at Darien in Central America is one of the best known episodes in late 17th century Scottish history. Most historians have naturally focused their attention on the dramatic events on the high seas and at the isthmus. The account set out here, which is the first major examination of the Company since John Prebble’s The Darien Disaster published in 1968, takes a different perspective. It is primarily concerned with the Scottish context; the directors who ran the Company, the shareholders who provided the cash to fund the venture, the mania for joint-stock investment that delivered such a very large amount of capital, and the financial and political repercussions of the disaster. The events in Central America were important and are considered in detail. However, what made the Company particularly significant was not its colonial aspects, for there had been a number of attempts by Scots to establish colonies during the 17th century, but rather its position as an instrument of financial innovation, and as a central ingredient in the complex financial and political settlement that created the United Kingdom in 1707. In the tercentenary year of Union, the strange circumstances which gave rise to this long-lasting marriage of convenience, or inconvenience, are of particular relevance.

Conventions

All monetary amounts in the text are in pound sterling unless specified, as the Company of Scotland raised capital and produced accounts in sterling. A separate Scottish currency existed until 1707 with an official exchange rate of £12 Scots to £1 sterling. Personal names and place-names have been modernised. In quotations, abbreviations have been extended, but 17th century punctuation, spelling and capitalisation left unaltered.

Introduction

ON 5 AUGUST 1707 a dozen wagons carrying a large quantity of money arrived in Edinburgh guarded by 120 Scots dragoons. A mob was waiting to hurl abuse as they trundled up to the castle to deposit their load and, on the way back down, to pelt them with stones. This was how the infamous ‘Equivalent’ was welcomed to Scotland; the huge lump sum paid to the Scots by the English government as part of the Treaty of Union of 1707; a bribe, bonanza or bail-out depending on your point of view. The stoning of those who delivered the Equivalent reflected the acrimonious divisions within the Scottish body politic, and is perhaps symbolic of the way in which Scots have viewed the Union ever since; repelled by the surrender of their national sovereignty, but at the same time willing to take the cash and opportunities it offers.

A large proportion of this money (about 59 per cent) was earmarked for a group of investors, the shareholders of the Company of Scotland trading to Africa and the Indies, now better known as the Darien Company. This was a joint-stock company which had attempted to establish a Scottish colony at the isthmus of Central America, in present day Panama. The fifteenth article of the Treaty of Union ended the existence of the Company and provided a generous bail-out package for shareholders, who received all the money they had invested 11 years before, and an additional 43 per cent in interest payments. By 1706 most had expected to receive nothing as the Company had destroyed all its capital. Compensation by a foreign government came as a welcome but problematic surprise.

The United Kingdom of Great Britain was brought into being by the Treaty of Union of 1707. The history of the Company of Scotland was intimately connected with the creation of this new political entity. At the heart of the achievement of Union was not economic theory or political ideology but rather that ‘root of all evil’, money. Not the money paid in secret bribes to buy support of key politicians, although this was important, or the money to be made in the future by exploiting access to English colonial markets, but the money paid immediately as part of the transaction between the two parties; the political elites of Scotland and England.

In 1696 the Scots had experimented with financial capitalism to a degree that many would have thought was beyond the resources of a relatively poor northern European nation. They had invested capital in a joint-stock company which promised to develop colonies and boost the domestic economy. In large numbers they had handed over coins or bullion to the Company in return for a share of future wealth. This was a remarkable event and one that can only be fully understood, it will be argued, if viewed as an early example of a financial mania.

The Company failed and every penny of capital was lost. The Scots experienced the destructive force of the new financial world more acutely than any nation before them. A dose of realism followed which encouraged the political elite to trade sovereignty and independence for the more prosaic prospects of security, economic growth and cash in hand. What follows is a history of how this happened.

CHAPTER ONE

The Strange Dream of William Paterson

It will be manifest that trade is capable of increasing trade, and money of begetting money to the end of the world.

WILLIAM PATERSON, 17011

ON 16 JUNE 1699, William Paterson was helped on board the Unicorn, a ship belonging to the Company of Scotland, anchored off the coast of Darien in Central America. Like many of his fellow Scots he had succumbed to one of the tropical diseases prevalent there, possibly yellow fever or malaria. It was the last time he was to see the isthmus of America; a place which had obsessed him for much of his life. Scotland’s colony was being abandoned after only seven months and Paterson’s vision of a trading entrepôt lay in tatters. Given his grim personal circumstances, and the disastrous attempt to establish a settlement, it might be expected that he would have sickened of the place, but on his return to Scotland he was to praise Darien in even more fulsome terms.

Paterson was a controversial figure in the 1690s. Within months of becoming a director of the Bank of England he had alienated the rest of the board and was forced to resign.2 The London merchants Michael Kincaid and John Pitcairn regarded him as a ‘downright blockhead’ and Robert Douglas, a merchant experienced in the East Indies trade, described him as ‘one who converses in Darkness and Loves not to bring his deeds to the Light that they may be made Manifest.’3 Walter Herries, who sailed as a surgeon with the first expedition to Darien, and became one of the severest critics of the directors of the Company, called him a ‘Pedlar, Tub-preacher, and at last Whimsical Projector’.4

Others were greatly impressed by this serious middle-aged financier. Poems were penned in Edinburgh in 1696 and 1697 to celebrate the ‘judicious’ and ‘wise’ Paterson. In one particular ballad, Trade’s Release: or, Courage to the Scotch-Indian-Company, he was compared with the biblical Solomon:

Come, rouse up your Heads, Come rouse up anon!

Think of the Wisdom of old Solomon,

And heartily joyn with our own Paterson,

To fetch Home INDIAN Treasures.5

On 19 February 1696, Paterson and his business associates Daniel Lodge and James Smyth were made burgesses and ‘gildbrethren’ of the Scottish capital, and the Merchant Company of Edinburgh awarded the same triumvirate ‘Diplomas in best form’.6 These were impressive accolades and reflected the reverence in which Paterson was held at the time.

He was sought out in the coffee-houses of Edinburgh by lairds, nobles, doctors and lawyers eager to hear his ideas about trade, colonies and companies. ‘Happy was he or she that had the Favour of a Quarter of an Hours Conversation with this blessed Man’ commented Herries.7 One historian has viewed him as a ‘merchant statesman’ and proselyte of free trade, and another as ‘the Man who Saw the Future’ – apparently he anticipated the global economy of the twenty-first century but not, unfortunately, the disaster that was to follow the attempt to establish a colony at Darien by the Scots of the late seventeenth.8 In a more balanced account he has been portrayed as a ‘financial revolutionary’, a man intimately involved with, indeed one of the principal figures in the financial revolution of the 1690s.9 This ‘revolution’ is not as famous as other ones beloved of historians, for it lacks a great central image, like the storming of the Bastille or the execution of a monarch, but in common with its more famous cousins it ushered in important aspects of the modern world. This sedentary revolution involved debate, disagreement, and the buying and selling of bonds and shares in the coffee-houses of London. It resulted in an explosion of capital markets that allowed the English government and companies to raise sums of money in larger amounts and more quickly than ever before. The 1690s witnessed the growth of a liquid government debt market and the first boom in the stock market. This was the era when stockbrokers, derivatives and a financial press make their debut in the field of British history and terms such as ‘bull’ and ‘bear’ were first used to describe those who were either optimistic or pessimistic about the direction of share prices.10

Paterson was described by contemporaries as a ‘projector’. He was one of the characteristic figures of what Daniel Defoe called the ‘Projecting Age’; one of the men who organised company capital raisings and persuaded investors to part with their money. Living by his wits, he was something like a mixture of a modern day investment banker and a stockbroker.

It is clear from his letters that he recognised an important feature of the new financial era; capital markets could be irrational in nature, reflecting the changing emotions of their human participants. In a letter to the Lord Provost of Edinburgh in 1695, he noted that ‘if a thing goe not on with the first heat, the raising of a Fund seldom or never succeeds, the multitude being commonly ledd more by example than Reason’.11 Paterson understood how the herd mentality, or the madness of crowds, as it was to be called, might be manipulated by those launching a company to raise huge sums of money in a short time, anticipating the speculative manias of the future, such as the South Sea and Internet bubbles.

Paterson’s skills lay in communicating the new age and at heart he was a gifted salesman. He sold shares in the Hampstead Water Works, a company established in London in 1692 to help supply the city with water. He sold shares in the Bank of England, founded in 1694 as a mechanism to supply cash for King William’s war effort; and he sold shares in the Orphans’ Fund, an investment vehicle recapitalised in 1694–5. He also, most remarkably, sold shares in the Company of Scotland to a relatively large number of Scottish investors at a time when Scotland was not at the forefront of financial powers. Finally, he sold his great idea of an emporium in Central America at Darien, which would act as a magnet for merchants and capital and control the trade to the East Indies, to the directors of the Company of Scotland. He even sold this idea to himself, although there is no evidence that he had ever been to Darien before. Paterson was able to achieve all this because of his gifts as a communicator. His writings mixed sober finance with flourishes of powerful poetry. The lyrical peaks that are glimpsed intermittently in his prose perhaps echoed the Covenanting preachers of his native Dumfriesshire, and proved a very persuasive tool for raising the mundane topics of cash, companies and credit onto a higher level, and making it more likely that potential investors would part with their money. Thus for Paterson a colony at Darien would be the ‘keys of the Indies and the doors of the world’ or the ‘door of the seas and the key of the universe.’ The two oceans linked by his vision, the Atlantic and Pacific, were ‘the two vast oceans of the universe’. Trade and money would increase ‘to the end of the world’.12 And in his most quoted passage, in which he praised the potential of an emporium at Darien, he brought together all his favourite sound bites to provide a piece of powerful poetry, indeed a hymn to the mystery of trade and capital:

Trade will increase trade, and money will beget money, and the trading world shall need no more to want work for their hands, but will rather want hands for their work. Thus this door of the seas, and the key of the universe, with anything of a sort of reasonable management, will of course enable its proprietors to give laws to both oceans, without being liable to the fatigues, expenses and dangers, or contracting the guilt and blood of Alexander and Caesar.13

It is easy to see why so many were influenced by him. Although these words were written in a pamphlet after his return from Darien, they surely echo the kind of language he used in 1696 when persuading Scottish nobles, lairds, merchants, lawyers, doctors, soldiers and widows to invest in the Company of Scotland.

Despite his visionary invocations, however, Paterson was selling an old idea. The Spanish reached Darien in the early 16th century, 197 years before the Scots. Rodrigo de Bastidas was the first European to land on the isthmus in 1501 and a colony was established at Darien by Vasco Núnez de Balboa in 1510. Three years later the local inhabitants, the Tule, led Balboa through the rainforest to reach the South Sea, or Pacific Ocean. In 1519 Pedro Arias de Avila founded Panama City on the Pacific coast, which became the seat of Spanish power when Darien was finally abandoned in 1524. The Spanish viewed the isthmus as a vital link between north and south, east and west, where the interests of the entire world would meet under their control.14 There were even plans in the 16th and 17th centuries to link the two oceans by a canal.15

By the middle of the 16th century the isthmus was the fulcrum of the Spanish imperial economy. Each year convoys of merchantmen protected by armed ships sailed up the Pacific coast of South America, loaded with silver from vast mines such as Potosi (in modern day Bolivia). At Panama City, on the south side of the isthmus, the treasure was packed on mules across to Portobello on the north, and then transported by the Spanish ‘galeones’ fleet to Seville or Cadiz.

Gold and silver lay at the heart of Spanish imperialism, rather than trade. In the early years artefacts looted from the indigenous peoples provided the principal source, but after the great ‘meltdown’ of 1533 the mining industry was expanded.16 There has been disagreement among historians about the quantities of silver transported across the Atlantic to Spain during the 17th century. It has been argued that by the end of the century the mines of America faced exhaustion and amounts declined.17 But the use of unofficial sources indicates that in the late 17th century bullion shipments were in fact reaching new highs.18 Paterson’s colonial project was not therefore centred on a pleasant backwater, but on an area of huge financial and strategic importance. As a contemporary pamphlet put it: ‘the Company has settled their Collony in the very Bosom and Centre of the three chief Cities of the Spanish-Indies, to wit, Carthagena, Portobello, and Panama, the first being about 45 Leagues, and the other two not above 30 distant from the Collony.’19 Why the Scots believed they could maintain a settlement in the centre of the Spanish empire remains one of the great mysteries of the history of the Company of Scotland and is a question we shall return to later.

Paterson had been trying to sell his Darien ‘project’ for many years. In a pamphlet of 1701 he recalled the ‘troubles, disappointments, and afflictions, in promoting the design during the course of the last seventeen years’.20 Robert Douglas, a merchant with experience in the East India trade, who wrote a long criticism of Paterson’s ideas in 1696, recalled that:

The design he was carrying on in Holland at Amsterdam some years ago particularly in 1687 when I had occasion to reside in that City about six months together and was often tymes at the Coffee houses where Mr Paterson frequented and heard the Accompt of his design which was to Erect a Common Wealth and free port in the Emperour of Dariens Countrey (as he was pleased to call that poor Miserable prince) whose protection he pretended to be assured of for all who wold engage in that design.21

In 1688 Paterson travelled to the German state of Brandenburg with the merchants Heinrich Bulen, Wilhelm Pocock and James Schmitten, looking for a sponsor to back his plans for an American colony, presumably at Darien.22 Although the Elector of Brandenburg decided not to support Paterson’s project, the joint-stock Brandenburg Company seems to have been influenced by his arguments, for it attempted to secure a footing at Darien in the late 17th century, probably the 1690s, but was repulsed by the Spanish.23 Brandenburg, like Scotland, was looking for a colonial base in the Caribbean and had sought to buy, lease or occupy a series of sites including St Croix, St Vincent, Tobago and Crab Island near St Thomas, but these attempts failed because of French, English or Dutch opposition.

The reason for Paterson’s obsession with Darien remains as obscure as his own early years. He left Scotland at a young age and, according to Walter Herries, became a merchant in the Caribbean, which was then experiencing a period of explosive commercial growth. In 1655 the English seized Jamaica from Spain, and the island became a significant centre for contraband trade with the Spanish empire. This was the so-called ‘Golden Age of Piracy’ when buccaneers infested the Caribbean seas. Pirates were active in Darien itself, suggesting that despite its importance to Spain the area was difficult to control, especially the eastern part of the isthmus.24 The Welsh buccaneer Henry Morgan captured Portobello in 1668 with 400 men, and in 1671 he crossed the isthmus to sack Panama City. It took 175 pack animals to carry the booty back to the Caribbean.25 William Dampier, the ‘pirate of exquisite mind,’ traversed the Central American jungle in 1680 and, according to Herries, shared his experiences with Paterson.26 Lionel Wafer, a buccaneer who crossed the isthmus with Dampier, was involved in negotiations with the Company at a later date.

It is clear that by the time of his return to Europe in the 1680s Paterson was convinced that Darien might be utilised in a new way, outside the Spanish monopoly system. Other states had picked off pieces of Spain’s Caribbean cake over the previous century. The English had taken the island of St Kitts in 1624, Barbados in 1625, St Vincent in 1627, Barbuda and Nevis in 1628, Montserrat, Antigua and Dominica in 1632 and most significantly Jamaica in 1655. The French grabbed Guadaloupe and Martinique in 1635, Granada and St Barthelmy in 1640 and St Lucia in 1660, and in 1697 obtained possession of St-Domingue (modern day Haiti). The Dutch had seized the islands of Curaçao in 1634 and Tobago in 1678, and even the Danes had staked a claim to the small island of St Thomas in 1672. Were the Scots not entitled to a share?

In July 1696 Paterson presented his plans to a committee of the directors of the Company of Scotland. By then he had been praising the virtues of Darien for many years and his argument was surely well polished. He backed up his words with maps and other documents:

The said Committee upon viewing and peruseing of several manuscript-Books, Journals, Reckonings, exact illuminated Mapps and other Papers of Discovery in Africa and the East and West Indies produced by Mr Paterson, as also upon hearing and examining several designs and schemes of trade and Discovery by him proposed.27

The directors noted in their minutes that Paterson had discovered ‘places of trade and settlement, which if duely prosecuted may prove exceeding beneficial to this Company’. Particular ‘discoveries’ of great significance were ordered to be committed to writing, sealed by Paterson and only opened by special order. At this stage Paterson was promoting a series of destinations, presumably including Darien, but the directors believed his information was of substantial value to the Company and resolved that ‘A settlement or settlements be made with all convenient speed upon some Island, River or place in Africa or the Indies, or both for establishing and promoting the Trade and Navigation of this Company’. The opaque language of the Company minute book seems to indicate that at this early stage a number of locations were being considered.

In early 1697 there was a change of emphasis. On 25 February a committee of the directors was appointed to consider ‘Mr Paterson’s Project’, as it was now being called. They resolved that without the help of significant amounts of foreign capital the Company ‘is not at Present in a condition or able to put Mr Paterson’s said design in execution’.28 They had decided to pursue a policy of retrenchment which involved selling ships and postponing the attempt to establish a colony at Darien.

However, they soon made another volte-face, which was to have profound repercussions. On 7 October the director Mr Robert Blackwood, an Edinburgh merchant, expressed his view that it was crucial that an immediate decision be made about the place or places to which the Company’s first expedition was to sail. He was probably reflecting the frustration of shareholders, many of whom were annoyed that little progress had been made in either trade or colonial development. A letter was sent to Mr William Dunlop, the principal of Glasgow University, who had been involved in the unsuccessful attempt to establish a Scottish colony in South Carolina in the 1680s, and who was viewed as an experienced hand in such matters, asking him to come to Edinburgh as quickly as possible to advise the directors. In the afternoon a committee was appointed to re-examine the issue: three lairds, Sir Francis Scott of Thirlestane, John Haldane of Gleneagles and John Drummond of Newton, and two merchants, Mr Robert Blackwood and William Wooddrop, were chosen. It is not spelled out explicitly in the Company records but it seems the committee recommended reverting to the original Paterson plan. This was then agreed by the full court of directors.

Like the Brandenburgers and the Scots, the English were also interested in the isthmus and were keeping a close watch on the Scottish Company. Indeed English interest in the area dated back to the days of the pirate Francis Drake, who raided Darien in the 1570s and died at Portobello in 1596.29 In English government circles there was initially some confusion about where the Company intended to trade, but in April 1697 a letter from Mr Orth, the secretary of Sir Paul Rycaut, English Resident in Hamburg, noted that the Scots were not interested in the East Indies or Africa, as their Company name suggested, but rather America and in particular the Gulf of Mexico.30

By June the English government had precise intelligence about the Company’s plans, although the Scots were in fact having second thoughts at this point. An English commission for ‘promoting trade and inspecting and improving Plantations’ called Dampier and Wafer to attend ‘to enquire of them the state of the Country upon the Isthmus of Darien where signified Scotch East India Comp have a design to make a settlement’.31 On 2 July Dampier and Wafer were questioned and on 10 September it was recommended that an expedition be sent from London or Jamaica to take possession of the area for England. Captain Richard Long, who had offered his services to salvage wrecks off the north coast of Darien, was provided with a commission and a ship, the Rupert prize, and set sail for the isthmus on 5 December 1697.32 The English government therefore had a clear idea where the Scots were heading before the Company of Scotland had come to a definite conclusion about their destination. The efforts of the directors to maintain secrecy had been a waste of time. It was well known in merchant circles that Paterson had been peddling the plan for years. Don Francisco Antonio Navarro, the Spanish Resident in Hamburg, was informing the Spanish crown of Scottish designs on Darien from July 1697.33 But while the English and Spanish knew where the Scottish expedition was sailing, some of the Scots who left on the first voyage in the summer of 1698 were not so clear about their destination. Ensign William Campbell of Tullich believed he was heading for Africa.34

Thus, under the influence of William Paterson, a Scottish joint-stock company decided to establish a colony in a vital area of the Spanish empire. This was an ambitious and, as it turned out, foolhardy decision, but other small European nations were looking for colonial crumbs in the Caribbean at the same time. What gave the Darien project its particular importance was the large number of Scots who invested in the Company, not just merchants from Edinburgh and Glasgow, but many nobles, and a large number of lairds, doctors, lawyers, soldiers, craftsmen and ministers. There was also a significant number of female investors; nobles, widows and the daughters of lairds and merchants. Success or failure would impact a relatively large part of the Scottish political nation. The capital that was raised gave the directors of a Scottish company, for the first time, immense financial muscle. For a few months they were in a much stronger position than the Scottish government, which had significant problems raising revenue in the later 17th century. Briefly the Company became a ‘state within a state’. What they did with their cash would therefore have considerable political as well as financial implications.

1 William Paterson, A Proposal to Plant a colony in Darien; to protect the Indians against Spain; and to open the trade of South America to all nations (London, 1701) in The Writings of William Paterson, Founder of the Bank of England, ed. S. Bannister, 3 vols (1968, New York), i, 158.

2 Bank of England Archive, Minute Book of the Directors, 27 July 1694 to 20 March 1694, 164, 166, 171.

3 Edinburgh City Archive [ECA], George Watson and George Watson’s Hospital, Acc 789, Box 8 Bundle 1, National Library of Scotland [NLS], Darien Papers, Adv MS 83.7.4, f23.

4 Walter Herries, A Defence of the Scots Abdicating Darien: Including an Answer to the Defence of the Scots Settlement there (1700), epistle dedicatory.

5 Various Pieces of Fugitive Scottish Poetry; principally of the seventeenth century, second series, 2 vols (Edinburgh, 1853).

6 Extracts from the Records of the Burgh of Edinburgh 1689 to 1701, ed. H. Armet (Edinburgh, 1962), 190, ECA, Minutes of the Merchant Company, i, 1696–1704, 4.

7 Herries, Defence, 5.

8 S. Bannister, William Paterson, The Merchant Statesman and Founder of the Bank of England: his Life and Trials (Edinburgh, 1858), A. Forrester, The Man Who Saw the Future (London, 2004).

9 D. Armitage, ‘ “The Projecting Age”: William Paterson and the Bank of England,’ History Today, 44, (1994), 5–10.

10 P.G.M. Dickson, The Financial Revolution in England: A Study in the development of Public Credit 1688–1756 (Aldershot, 1993), 503.

11 The Darien Papers, ed. J.H. Burton (Bann. Club, 1849), 3.

12 Writings of William Paterson, i, 147, 158–9.

13 J. Prebble, Darien: The Scottish Dream of Empire (Edinburgh, 2000), 12.

14 D.R. Hidalgo, ‘To Get Rich for Our Homeland: The Company of Scotland and the Colonization of the Isthmus of Darien,’ Colonial Latin American Historical Review, 10 (2001), 312–13.

15 R.L. Woodward, Jr. Central America: A Nation Divided (Oxford, 1999), 120.

16 J.R. Fisher, The Economic Aspects of Spanish Imperialism in America, 1492–1810 (Liverpool, 1997), 25, 27.

17 Ibid., 75, 100.

18 H. Kamen, Spain in the Later Seventeenth Century, 1665–1700 (London, 1980), 136.

19 Herries, Defence, 164.

20 Writings of William Paterson, 117.

21 NLS, Adv MS 83.7.4, f23–4.

22 F. Cundall, The Darien Venture (New York, 1926), 10.

23 Companies and Trade, (eds.) L. Blussé and F. Gaastra (The Hague, 1981), 169.

24 I.J. Gallup-Diaz, The Door of the Seas and Key to the Universe: Indian Politics and Imperial Rivalry in the Darién, 1640–1750 (New York, 2005), xviii–xix.

25 H. Kamen, Spain’s Road to Empire: The Making of a World Power, 1692–1763 (London, 2002), 428.

26 D. and M. Preston, A Pirate of Exquisite Mind: The Life of William Dampier (London, 2004), 53–61. He was called this by the poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge. Herries, Defence, 4–5.

27 The Royal Bank of Scotland [Group Archives] [RBS], Court of Directors Minute Book, D/1/1, 105.

28 Ibid., 25 February 1697.

29 Oxford Dictionary of National Biography [ODNB], (eds.) H.C.G. Matthew and B. Harrison, 61 vols (Oxford, 2004), 16, 858–69.

30 Papers Relating to the Ships and Voyages of the Company of Scotland trading to Africa and the Indies 1696–1707, ed. G.P. Insh (SHS, 1924), 34–5.

31 Ibid., 48–9.

32 Gallup-Diaz, Door of the Seas, 87–9.

33 Ibid., 82–3. One letter from Navarro reported that the Scots also had designs on Chile and an island in the Straits of Magellan.

34 National Archives of Scotland [NAS], Breadalbane Muniments, GD 112/64/14/21.

CHAPTER TWO

Imperial Bliss

Our Thistle yet I hope will grow Green.

LORD BASIL HAMILTON1

THE DIRECTORS OF THE Company of Scotland were summoned to an impromptu meeting by secretary Roderick MacKenzie on the afternoon of 25 March 1699. They met, as was usual, in the Company offices at Milne’s Square on the High Street of Edinburgh, opposite the Tron Kirk. Mr Alexander Hamilton, a messenger from the other side of the Atlantic, was called into the chamber and ‘very joyfully’ received. He was the bearer of intoxicating news: the Company of Scotland had achieved its aim of establishing a colony at Darien on the isthmus of Central America. At last Scotland could think of itself as an imperial power.2

Rumours about this miraculous event had been circulating before the directors received official confirmation. George Home of Kimmerghame, a Borders laird and shareholder in the Company, had noted in his diary as far back as 18 January that the fleet of five ships had reached an unknown destination in America. The press also had wind of the story; a letter was published in the Edinburgh Gazette announcing the location of the colony and the paper had to apologise for pre-empting an official announcement by the directors. The scoop was, however, too good to ignore and on 23 March the Gazette ran the following advertisement: ‘There is now in the Press a short Description of the Isthmus of Darien, Gold Island and River of Darien, chiefly in relation to these parts where the Scots African Company are said to be’. This was published in the next few days at a price of seven pence Scots.3 The ‘Scots African Company’ was one of the many contemporary names applied to the Company of Scotland trading to Africa and the Indies.

As well as bearing sensational news, Hamilton delivered a large sealed packet containing a journal of events on the voyage and at the isthmus, and a letter from the Council of the colony. He also carried more sobering information; a list of those who had died in the Company’s service. Alexander Piery had been the first to succumb to fever on 23 July 1698, and Lieutenant John Hay’s wife the first woman on 19 October. The printed news-sheet did not provide her Christian name. Mr Thomas James, one of the two ministers, died on 23 October and Thomas Fenner, William Paterson’s clerk, on 1 November. Both were consumed by ‘fever’. In total 44 had died on the ships and another 32 perished after reaching the isthmus, including Henry Grapes, a trumpeter, Hannah Kemp, William Paterson’s wife, Mr Adam Scott, the other minister, the two boys William MacLellan and Andrew Brown, and Recompence Standburgh, a mate on the St Andrew, whose English name reminds us that there were some colonists from other nations. The death rate of 76 from a total of 1,200 (6.3 per cent) was not regarded as excessive and indicates the risks of long-distance travel in the 17th century. The list was immediately published by the Company and proudly proclaimed that:

It may be some Satisfaction to the nearest friends of the deceased that their names shall stand upon Record as being amongst the first brave Adventurers that went upon the most Noble, most Honourable, and most Promising Undertaking that Scotland ever took in hand.4

The court of directors proceeded to make a number of resolutions; firstly that no time be lost in supplying the colony with provisions, secondly that a reward be given to Mr Hamilton for bearing such good news and finally that the ministers of Edinburgh and its suburbs be officially informed of the Company’s success ‘to the end that they in their discretion, return publick and hearty thanks to Almighty God’. The Edinburgh Gazette reported that on the next day, Sunday 26 March, after their sermons, the ministers carried out the request.5 The sparse minute book of the directors provides no further details about this auspicious occasion, so we can only imagine the sense of achievement felt by those who ran the Company. A number had worked tirelessly over the three years since capital was raised in 1696. There must have been great satisfaction for the men at the heart of the management: the lairds Sir Francis Scott of Thirlestane and John Drummond of Newton, the soldier Lieutenant Colonel John Erskine, and the Edinburgh merchants James Balfour and James MacLurg.

At church in Edinburgh on Sunday, George Home of Kimmerghame heard confirmation of the news and wrote in his diary that the Scots had ‘fortifyed themselves in a bay the place they have called Caledonia the old name of Scotland and the toune they designe they have called New Edinburgh’. The patriotic symbolism was completed by naming their defensive position Fort St Andrew. Despite the exotic location the Scots had not established their colony in an unknown corner of the world. Darien was a famous location in the late 17th century. Just as the colonists were clearing the tropical jungle, at home in the Borders George Home was reading A New Voyage Round the World, the best-selling travelogue by William Dampier, the buccaneer turned travel writer, which included a description of the Darien isthmus and was published in 1697.6 Another best selling work, A New Voyage and Description of the Isthmus of America by Lionel Wafer, who had been in Darien with Dampier, was to be published in 1699. For many Scots therefore the word ‘Darien’ carried connotations of exoticism, adventure, buccaneers and wealth. As news of the establishment of the colony spread there must have been raised eyebrows in the coffee-houses of London, Amsterdam and other European cities. Scotland was a relatively poor northern European nation and such an attempt was audacious to say the least.

Mr Hamilton, the bearer of such glad tidings, was generously rewarded. The directors agreed to give him one hundred guineas; a very large sum for the late 1690s, equivalent to about £10,000 in today’s money, and we might imagine that he would not have received such a handsome bonus if the news he had brought home had not been so hopeful.7 It was also generous because the Company’s cash reserves were under pressure, and it marked a significant personal achievement for the young Hamilton, who in March 1698 had been described as ‘idle’, and had only been appointed as chief accountant on the expedition through the efforts of his uncle.6

Other mouth-watering rumours were circulating. According to Mr Robert Blackwood, one of the directors, the indigenous people of Darien, the Tule, had assured the Scottish settlers that there was a gold mine within two days journey of the colony.7 From the isthmus Samuel Veitch wrote to the Earl of Annandale that the settlement was situated in the very centre of the ‘riches of America’, within two or three days march of six gold mines. Three of these were mined by the Spaniards and three were not worked because of a lack of slaves. The Tule had promised to guide the Scots to the mines and assist in seizing them.8

The author of a contemporary pamphlet informed his readers that the Darien gold mines were so well endowed that each slave working them might produce a daily profit of thirty louis d’or (French gold coins) and provide in a week what an English sugar plantation would make in a year.9 Another pamphlet stated that the precious metal reserves would outstrip those of Peru; indeed Peruvian gold and silver was ‘like a Mouse to an elephant in comparison of the Mines of Darien’. The writer described other riches including silver horseshoes, jewel-encrusted bridles and household vessels of gold and silver. Perhaps realising that he might be stretching the credulity of his readers he concluded: ‘I could Write much concerning vast Riches that are there in these places; but I know that my Countrey-men are generally Thomasses’.10

A small book published in 1699 called The History of Caledonia waxed lyrical on the same theme:

The Country tho it be Rich and Fruitful on the surface, is yet far Richer in its Bowels, there being great Mines of Gold; for the Deputies were certainly informed that not above twelve Leagues from New Edenborough, was a great Mine of this pretious metal, on which were employed near a Thousand Blacks, and that in the River of Sancta Mena; which is not above Thirteen Leagues from this Colony, and which falls into the South Sea, the Spaniards every year get Gold dust to the value of a Million.11

Physical manifestation of the potential wealth of Darien was soon appearing in Edinburgh as small pieces of gold that had been sent home by the colonists circulated in the coffee-houses off the High Street.12 Perthshire laird and director John Haldane of Gleneagles proudly exhibited a gold lip-piece.13 The appearance of such items must have had an electrifying effect on shareholders of the Company; a clear indication that they had been right to invest. It was also a clever public relations exercise, making it more likely they would provide further cash for the Company as calls were made by the directors. Although the Darien project was officially conceived as an attempt to develop Scottish trade and boost the domestic economy, these extracts reveal that a strong motive was the magnet that had pulled thousands of adventurers across the Atlantic in the 16th and 17th centuries, the desire for gold and silver.

On 29 March the directors were back at business and resolved to send the Rising Sun and two smaller ships, with 500 colonists and 200 seamen. As a mark of long-term commitment they hoped that one hundred women might be encouraged to go. They also decided to raise more capital to fund relief ships at this ‘extraordinary juncture’ and a council general of the Company was convened to sanction this. Sixteen directors and 25 representatives of shareholders attended the following day and authorised a 5 per cent call on the subscribed capital of the Company. This would involve each shareholder giving five per cent of the amount they had subscribed. They had already provided 25 per cent of their subscription in cash. Authority was also given for a further 2.5 per cent if required and it was agreed that letters giving an account of the establishment of the colony should be sent to the King and the two Scottish secretaries of state in London.14

Many were swept along in the frantic optimism of these months. Lord Basil Hamilton, who later became a director, praised Darien in a letter to his older brother, the Duke of Hamilton:

A fine Countrey a good harbour and what not and very well received by the inhabitants … if this affair goe on as it begins, I think it the greatest happiness, and advancement that could befall this poor Nation, and which may lift up our heads which wer joust a sinking … its not to be told you how joyfullie it is received by all people, Our Thistle yet I hope will grow Green.15

Samuel Veitch wrote from Darien praising the location: ‘for the conveniency of the harbour and being easily fortified can scarse be paralleled in all this vast Continent’. He added that a thousand ships might be protected from storms within the harbour and that the promontory was the ‘pleasantest situation for a toun in the world’.16 Descriptions also highlighted the burgeoning fertility of the land and the exotic array of commodities, such as indigo, cacao and Nicaragua wood, which would soon be in the hands of the Scots.

There was, however, one discordant note amongst all the celebrations and back-slapping, which was to return as a chord and then a symphony of criticism. Lord Basil Hamilton noted the arrival in Bristol of Walter Herries, a native of Dumbarton, who was employed as a surgeon on the first expedition, but had left the colony disillusioned and was, according to Lord Basil, making up stories about the mismanagement of the directors.17 Herries spent the time after his return writing an account of his experiences, which was published in 1700 as A Defence of the Scots Abdicating Darien. It was a vitriolic, abusive and powerfully written attack on the directors and has become the historical source most relied on by historians of the Company. Its pronouncements, however, must be treated with some care given its viciously partisan nature.

For a few blissful months in 1699 the Scots were a colonial power and the talk of Europe. Darien was not, however, the first Scottish colonial venture of the 17th century. An attempt was made by Sir William Alexander of Menstrie to establish a colony in Nova Scotia in the 1620s, until Charles I sold the land back to the French in 1632. In 1681 a memorial was prepared for the Scottish privy council, addressing the question of possible locations for a colony. The Caribbean islands of St Vincent and St Lucia were regarded as ‘very fitt and proper.’ Cape Florida and the Bahamas were also proposed, and it was suggested that the English might allow the Scots to colonise part of Jamaica.18 Darien, it should be stressed, was not mentioned. Two unsuccessful attempts to establish settlements followed in the 1680s at East New Jersey and South Carolina, but both were relatively small in scale. East New Jersey ultimately merged with the English colony of New Jersey and the settlement in South Carolina was destroyed by a Spanish force in September 1686.

Although Scotland had failed to establish colonies, many Scots had crossed the Atlantic by the late 17th century, with the majority settling in the islands of the Caribbean. Some were prisoners from Cromwell’s victories at the battles of Dunbar and Worcester, who were shipped out as indentured labour and had to endure seven years of back-breaking plantation work before receiving their freedom. Some were engaged in the logging trade in the Bay of Campeachy in present day Mexico. Others settled further north in New England, establishing the Scots Charitable Society in Boston in 1657.19 However, Scotland was well behind other nations in the imperial race.20 The Spanish and Portuguese established vast empires in the 16th century and the English and Dutch in the 17th. Now smaller nations like Denmark, Sweden and Brandenburg were seeking sites for colonisation. By the 1690s the Scots believed they needed colonies as markets for Scottish goods in an era of economic nationalism, or mercantilism, which saw their merchants and ships excluded from English colonial markets by the Navigation Acts.21 The establishment of Scottish colonies would boost the domestic economy and solve the perennial problem of unemployment of the poor.

The nascent media industry was not slow in taking advantage of the atmosphere of intense national excitement. Before the ships had sailed on the first expedition, poems, songs and ballads circulated celebrating the Company of Scotland and in particular the man at the centre of its early history, William Paterson. In early April 1699 George Home read a description of Darien written by a man called Isaac Blackwell, who claimed to have lived there for 17 years.22 The Company itself employed James Young to engrave a map and print a description of the colony.23 Sir John Foulis of Ravelston paid £6 Scots for one, and £5 Scots for a ‘Darien song’.24 Students at Edinburgh University were busy preparing theses on the legal rights of the Company to the isthmus and at their graduation ceremony Mr William Scott, professor of Philosophy, provided an ‘Elegant Harangue’ on the same theme.25 In Holland, John Clerk of Penicuik was moved to celebrate the Company’s success in a stirring cantata he composed, called Leo Scotiae Irritatus (The Scottish Lion Angered), with lyrics in Latin by his Dutch friend Dr Boerhaave. The words of a Dutchman caught the ecstatic mood of the Scots:

O cara Caledonia!

Deliciarum insula

O renovate Scotia!

Te querimus, te petimus.

Tu animas nostras trahis.

Daria suavis insula,

Sit Scotiae colonia.

Dear Caledonia!

Delightful country.

O Scotland renewed!

We ask you, we beseech you

To raise our spirits.

Darien, that sweet land,

Should be a Scottish colony.26

The majority of the nation was in a state of intense excitement but the news provided problems for the Scottish government. The chancellor Patrick Hume, Earl of Marchmont, wrote prophetically to Secretary of State James Ogilvie, Viscount Seafield, on 3 April:

There is ane unaccountable inclination among people here to goe thither and by what I can find that undertakeing is not likelie to want all the support this countrie is able to give it either of men or money … but as you hint There is either a great advantage or a great prejudice acomeing God knowes which.27

Government ministers were in a difficult position. Marchmont was a shareholder but found himself caught between two masters – King William and the Company of Scotland – and it was not possible to serve both. The Glorious Revolution of 1688–9 had brought William and Mary to the throne and seen Mary’s father, James VII of Scotland and II of England, forced into exile. William was already Stadholder of the United Provinces and now became King of England, Scotland and Ireland. His principal concern was opposing the expansionist policies of Louis XIV of France and most of his time was spent in London or on the Continent. He showed little interest in Scotland and never visited his northern kingdom despite many pleas for him to do so. Scots affairs were delegated to the Dutchman Willem Bentinck, Earl of Portland, who, like his master, never ventured north of the border. Under Portland in the administrative hierarchy was the King’s favourite, William Carstares, a Presbyterian minister who had been in exile in the Netherlands, and below him two Scottish secretaries of state based in London. This distant and inefficient structure highlighted the inadequacies of absentee monarchy which Scotland had experienced since the Regal Union of 1603, when James VI also became James I of England. From the beginning King William viewed the Company’s existence as an annoying distraction. The arrival of the Scots at Darien and the creation of a Scottish ‘empire’ in Central America would prove to be an even bigger diplomatic headache.

1 NAS, Hamilton Muniments, GD 406/1/6487.

2 RBS, D/1/2, 25 March 1699.

3 Edinburgh Gazette, no.7, 20–23 March 1699.

4 An ExactLISTof all Men, Women, and Boys that Died on Board the Indian and African Company’s Fleet, during their Voyage from Scotland to America, and since their Landing in Caledonia (Edinburgh, 1699).

5 Edinburgh Gazette, no. 8, 23–27 March 1699.

6 NAS, Diary of George Home of Kimmerghame, GD 1/891/2, 1 April 1699.

7 Hamilton was the brother of John Hamilton, bailie of Arran, NAS, GD 406/1/6488, Lawrence H. Officer, ‘Comparing the Purchasing Power of Money in Great Britain from 1264 to 2005,’ Economic History Services, 2005, http://www.eh.net/hmit/ppowerbp/.

6 NAS, Letterbook of Robert Blackwood, GD 1/564/12, 12 March 1698.

7 NAS, GD 406/1/4393.

8 National Register of Archives of Scotland [NRAS], Earl of Annandale and Hartfell, 2171, Bundle 825.

9 A Just and Modest Vindication of the Scots Design, For the having Established a Colony at Darien (1699), 173.

10 Description of the Province and Bay of Darian … Being vastly rich with Gold and Silver, and various Commodities. By I. B. a Well-wisher to the Company who lived there Seventeen Years (Edinburgh, 1699), 4.

11 The History of Caledonia: or, The Scots Colony in Darien in the West Indies. With an Account of the Manners of the Inhabitants, and Riches of the Countrey. By a Gentleman lately Arriv’d (London, 1699), 18–19.

12 Coffee-house culture had come to the Scottish capital during the Restoration and by the late 17th and early 18th centuries there were a number of coffee-houses in the closes, vennels and wynds off the High Street, including the Flanders, the Exchange, the Caledonian and the East India. They were relaxed meeting places where coffee or chocolate might be drunk and news, gossip and politics discussed.

13 NAS, GD 1/891/2, 5 April 1699.

14 RBS, The Acts, Orders and Resolutions of the Council General of the Company of Scotland, D/3, 30 March 1699.

15 NAS, GD 406/1/6487.

16 NRAS, 2171, Bundle 825.

17 NAS, GD 406/1/6484.

18 Register of the Privy Council [RPC], third series, vii, 664–5.

19 D. and M. Preston, Pirate of Exquisite Mind, 42.

20 Scottish colonialism may have been less developed because of Scottish emigration to Ireland during the 17th century. The northern counties of Ireland could be regarded as Scotland’s first colony.

21 By the English Navigation Act of 1660, all trade to and from the colonies was to be carried in English or colonial ships and the captain and at least three quarters of the crew were to be English or colonial men. N. Zahedieh, ‘Economy’ in The British Atlantic World, 1500–1800, (eds.) D. Armitage and M. J. Braddick (Basingstoke, 2002), 53.

22 NAS, GD 1/189/2, 3 April 1699.

23 RBS, D/3, 31 March 1699.

24 The Account Book of Sir John Foulis of Ravelston 1671–1707 (SHS, 1894), 252–3.

25 C.P. Finlayson, ‘Edinburgh University and the Darien Scheme,’ SHR, 34, (1955), 97–8.

26 NAS, Clerk of Penicuik Muniments, GD 18/4538/4/1–2. I would like to thank Sir Robert Clerk of Penicuik for permission to quote from Leo Scotiae Irritatus. A recording of the cantata with other music by Sir John is available from Hyperion Records Ltd, London.

27 NAS, Hume of Marchmont, GD 158/965, 101.