Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

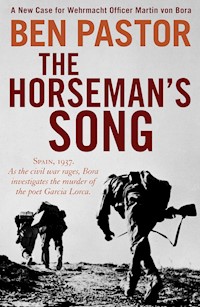

- Herausgeber: Bitter Lemon Press

- Kategorie: Krimi

- Sprache: Englisch

Wehmacht officer Bora is sent to recently occupied Crete and must investigate the brutal murder of a Red Cross representative befriended by Himmler. All the clues lead to a platoon of trigger-happy German paratroopers but is this the truth? Bora takes to the mountains of Crete to solve the case, navigating his way between local bandits and foreign resistance fighters.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 608

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2017

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Ben Pastor, born in Italy, became a US citizen after moving to Texas. She lived for thirty years in the United States, working as a university professor in Illinois, Ohio and Vermont, and currently spends part of the year in her native country. The Road to Ithaca is the fifth in the Martin Bora series and follows on from the success of Tin Sky, Lumen, Liar Moon and A Dark Song of Blood, also published by Bitter Lemon Press. Ben Pastor is the author of other novels including the highly acclaimed The Water Thief and The Fire Waker, and is considered one of the most talented writers in the field of historical fiction. In 2008 she won the prestigious Premio Zaragoza for best historical fiction.

Also available from Bitter Lemon Press by Ben Pastor:

Tin Sky

Lumen

Liar Moon

A Dark Song of Blood

BITTER LEMON PRESS

First published in the United Kingdom in 2017 by Bitter Lemon Press, 47 Wilmington Square, London WC1X 0ET

www.bitterlemonpress.com

Copyright © 2014 by Ben Pastor

This edition published in agreement with the author through Piergiorgio Nicolazzini Literary Agency (PNLA)

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced in any form or by any means without written permission of the publisher.

The moral rights of Ben Pastor have been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs, and Patents Act 1988

A CIP record for this book is available from the British Library

eBook ISBN 978–1–908524–81–2

Typeset by Tetragon, London

Printed and bound in Great Britain by CPI Group (UK) Ltd, Croydon, CR9 4YY

To all those who believe, with Wordsworth,

that the Child is father of the Man

Contents

Main Characters

Foreword

Part One: Setting Off

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Part Two: Wandering

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Part Three: Returning

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Afterword

Glossary

MAIN CHARACTERS

Martin Bora, Captain, German Army Abwehr

Frances L. Allen, American archaeologist

Andonis Sidheraki, her Cretan husband

Gottwald “Waldo” Preger, Captain, German Airborne Troops

Vairon Kostaridis, Police chief, Iraklion

Patrick K. Sinclair, First Lieutenant, Leicestershire Regiment, CreForce

Manoschek, Undersecretary, German Embassy in Moscow

Emil Busch, Major, German Army Abwehr

Bruno Lattmann, Captain, German Army Abwehr

Alois Villiger, Swiss scholar

Rifat Bayar Agrali, “Rifat Bey”, Turkish businessman in Crete

Pericles Savelli, Italian scholar

Geoffrey Caxton, English archaeologist

“Bertie”, Sergeant Major, CreForce

Margaret Bourke-White, US photographer

Erskine Caldwell, US author

Go back to the target you missed; walk away from the one you hit squarely.

CRETAN SAYING,

IN KAZANTZAKIS’ REPORT TO GRECO

A room lit to the most hidden corner is no longer liveable.

WERNER HERZOG,

I AM MY FILMS

Foreword

TO: Colonel Bruno Bräuer, Commander Airborne Regiment 1, 7th Flieger Division, eyes only

FROM: Medical Officer Dr Hellmuth Unger, Wehrmacht War Crimes Bureau

Colonel,

In the process of verifying reports of war crimes committed against German military personnel during the recently concluded operation in Crete, the following account came to my notice. As you will see, it is of a completely different – I would say opposite – nature, and, in view of possible pressures forthcoming from Messrs Brunel and Lambert of the International Red Cross, it may require immediate attention.

Yesterday, 31 May, a British prisoner of war of officer rank repeatedly insisted on being heard. Brought into my presence, he handed in a photographic camera, whose contents he urgently asked us to develop. The camera was entrusted to him by a fellow prisoner, an NCO who successfully escaped from the gathering point at Kato Kalesia. The photos (see attached) bear witness to an atrocity supposedly committed by troops belonging to Airborne Regiment 1: hence this preliminary note to you.

According to the officer, whose name, rank and unit I will include in my full report, the NCO told him he fell behind during retreat, and found himself alone, hiding from our victoriously advancing troops in a gully along a road some miles south of the so-called Chanià Gate, leading west from Iraklion’s city walls. An amateur photographer, he had a portable camera with him. From his hideout, he claimed he saw eight German paratroopers approach on foot along the road, and enter a property we have since identified as Ampelokastro, the residence of a prominent Swiss national. The men, armed with MAB 38 automatic weapons and Schmeisser submachine guns, reportedly pushed the gate open and disappeared from his view behind the garden wall. Being unarmed and outnumbered, the witness did not dare to draw close. Within minutes, immediately after a single pistol shot, a commotion followed by volleys of rapid gunfire came to his ear. The utter lack of sound after the shoot-out (“not even voices shouting in German”, which he fully expected) made him “hope that the paratroopers had fallen into a trap”, set by Allied soldiers hiding on the premises or by locals equipped by the British Army.

As reported to the officer, nearly a quarter of an hour went by before the NCO decided to attempt crawling into the garden to see. He met with no signs of life there. A watchdog had been shot dead on the steps leading inside the building, where total silence convinced him the paratroopers had perished or were no longer in the house. Indeed, the garden (as later that day I confirmed in person when I visited the scene) is provided with a back gate, reported to have been unlocked and wide open at the time. As soon as he stepped in, the photographer was met by the ghastly sight of an entire civilian household exterminated by gunfire.

While the eyewitness himself has thus far escaped recapture, the officer who reported the case is presently being held in the Galatas camp.

In the interest of truth, and given the potential repercussions of such a grave incident involving the illustrious citizen of a neutral country, I decided to contact you directly and with every urgency. My full report, marked “Ampelokastro, Eyes Only”, will be deposited at your office for you to choose how to proceed.

PART ONE

Setting Off

1

Nul tisserand ne sait ce qu’il tisse.

No weaver knows what he weaves.

FRENCH SAYING

SUNDAY 1 JUNE 1941, MOSCOW, HOTEL NATIONAL, 10.00 P.M. THREE WEEKS TO HITLER’S INVASION OF THE SOVIET UNION

If Martin Bora had known that in a thousand days he’d lose all he had (and was), his actions that day wouldn’t have appreciably changed. Today things were as they were.

On his bedside table sat a note that read Dafni, Mandilaria, and nothing else. Its heavy, slanted handwriting, however, lent it a certain importance. From a man whose signature could mean instant execution, as it had done for some forty thousand already, even the jotted names of southern wines sounded ominous.

Bora turned the note face down. He then opened his diary to a blank page and began, from force of habit, by censoring his real thoughts.

Maggie Bourke-White keeps fresh lilacs in her room. The scent fills the hallway on this large top floor; I perceive it whenever I go in or out. Her husband (see below) doesn’t like me at all, and it’s mutual; she’s more tolerant, or else has a photo reporter’s interest in strange animals, such as we Germans are in Moscow these days. But it’s all strange, or else I wouldn’t have on my night table a note in Cyrillic that reads Dafni and Mandilaria. I was quietly in a cold sweat at our embassy last night when I received it from Deputy Chairman of the Council of People’s Commissars and NKVD chief Lavrenti Pavlovich Beria. Stalin himself doesn’t unsettle me as much as his powerful head of secret police! I, a mere captain occasionally doubling as an interpreter, had additional reasons to be fidgety. Last Friday, returning late from one of the diplomatic circle parties – actually a Russian-style drinking bout of the kind I’m getting rather sick of – something happened that illustrates the strange world we move in. I got it into my head (I was tipsy after all the Starka and Hunter’s vodka, but not actually drunk) to take a left on Gorky and head for Triumphal Boulevard and Nikitskaya, where the Deputy Chairman has his city residence. It was two minutes past midnight; I supposed there wouldn’t be much going on at that time, even though Soviet officials earn affectionate nicknames such as “stone arse” because of the long hours they reportedly spend sitting at their desks. Well, either those stories are true, or else the NKVD were ticked off for whatever reason: they stopped me around the corner despite all official papers and the propusk glued to my windscreen, and gave me (or tried to give me, I should say) the once-over. They made me leave the car and questioned me for several minutes. “Is your name Martin Bora (pronounced Marty’n Bwora)?” “Yes.” “Do you reside at the Hotel National?” “Yes.” “Then what are you doing here?” “Don’t know. Where’s here?” “Have you been drinking?” “Yes.” And so on. It all simmered down once I pretended to be soused beyond redemption. Had they been patrolmen, I’d have offered cigarettes. As foreign tobacco is at a premium in the Soviet Union, it often opens doors and shuts mouths. But with members of the secret police I wouldn’t be so glib. In the end they grumbled an admonition and let me go. Did they believe I’d got lost in the foreigners’ district? I doubt it. Will they report me to whomever? Of course. But we all play these games in Moscow nowadays: diplomats, soldiers, privileged westerners.

Speaking of the latter, just yesterday, as I waited below for the hotel lift, I ran for the fourth or fifth time into best-selling American author Erskine Caldwell. He resides here with his lilac-loving wife Margaret, or Maggie, and enjoys the superlative kid gloves treatment from Molotov’s Narkomindel. While our embassy personnel have been restricted from travelling outside Moscow, the couple freely (or so they think) ride and fly about for their articles. I am under orders to act engagingly with non-belligerent foreigners, so I always greet Caldwell first.

As usual, the leftist globetrotter who broadcasts starry-eyed reports from Moscow to the US ignored me. But he couldn’t very well pretend not to see a fellow who exceeds his football player’s height, speaks perfect English and is attired as a military attaché’s adjutant besides. Be that as it may, like a cowboy peering into the distant prairie, Caldwell stared elsewhere. I didn’t insist. Mrs Bourke-White wasn’t with him, but I’d met her in the hotel restaurant before. Perky rather than pretty, she strikes me as intelligent, outspoken, a news photographer by trade who has travelled half of the known world. A Bavarian who deals in optical instruments has been trying to hit on her, banking on his status as a civilian who can boast of the third-floor suite with a grand piano and Napoleonic knick-knacks. It seems the two Caldwells get along fine – although he’s rumoured to be short-tempered, and we’ll see how long a free-thinking Yankee woman will put up with that. It’d be all plain gossip if I weren’t aware of the role these intellectuals play in today’s rapid communications. I keep an unobtrusive eye on them through E., a close associate of theirs, whom they trust and at most assume will report to Comrade Stalin exclusively.

Additionally, all of us – Soviets, Germans, others – make expedient use of the motley humanity crowding that repository of émigrés, the dilapidated Hotel Lux, former Zentralnaya, also known as the “golden cage of the Comintern”. The intrigue up and down its six floors reminded one of Vicki Baum’s Grand Hotel. The residents have a desperate need for amenities – what am I saying, the basics as one understands them in the civilized world: soap, toilet paper, light bulbs, etc.

Bribery is not impossible, though the residents know it might cost them their neck. They’ve been decimated in the last four years, despite every last one of them being communists; I should know, I have to pore over back issues of the now defunct Deutsche Zentral-Zeitung, which spewed out their red propaganda for years.

Back to Lavrenti Pavlovich Beria. In his armoured Packard, last night he showed up uninvited at Ambassador Count von der Schulenburg’s informal get-together for a few selected guests, which is how I got my homework sketched by him on a notebook page. For whom (or what) is the third most powerful man in Russia requesting sixty bottles of choice Cretan wine?

After a meeting that exuded goodwill but remained tense, we were wracking our brains to understand it (private use, a major bash, a present to US Ambassador Steinhardt?). For all we know, in a roundabout way the wine could be meant as a gift for our own Foreign Minister. Naturally, my superior, Colonel Krebs, agreed at once to send me all the way to Crete to secure the delicacy. Never mind that we’ve barely concluded a victorious if hard-won campaign to conquer that island.

Officially the airborne operation closed yesterday. As per my orders, tomorrow – the major hailstorm of the past hours having abated – I’m off to Lublin on a Russian plane. From there on German wings I’ll continue on to Bucharest, and then south to Athens. At Athens I’ll hitch a ride somehow, possibly on one of the seaplanes that fly the route to Crete, or one of the ambulance Junkers likely going to and fro since the battle.

Does being a soldier include such unglamorous chores as providing wine for our Russian allies? Apparently so. Enough for a diary entry. Wake-up time in five hours, 1 a.m. Berlin time, 3 a.m. Moscow time.

MONDAY 2 JUNE

Without daylight saving time, at 3.30 dawn was already breaking in Moscow. Bora pocketed Lavrenti Pavlovich’s note without rereading it.

The truth is, what made me curious about his house off Triumphal Boulevard wasn’t the accounts of his work habits, but insistent rumours about his penchant for luring underage girls no one hears from afterwards. Improbable? He didn’t hesitate to arrest the wife of Stalin’s personal secretary, and they say he’ll send her to the firing squad! No wonder they stopped me at the street corner.

He felt his jaw for smoothness after shaving, lifted his tunic from the back of the chair and put it on. The task of packing the small bag he’d take for the trip was quickly disposed of. When the waiter knocked discreetly on the door, Bora answered, “Da, kharasho,” without opening it, so that he’d leave the tray on the threshold. He’d sent for room service to save time. Because all hotel personnel worked for the secret police one way or another, and a guest assigned to the German Embassy was sure to be carefully scrutinized, Bora waited until the dying footfalls outside told him the man had gone, and then unlocked the door.

Cup in his hand in front of the open window, he breathed in the brisk air, where droplets of moisture coalesced without actually becoming mist. From the street below, it was possible the higher floors of this and other buildings would soon appear swathed in fog. The spires of the nearby Citadel were already. One of the coldest springtimes on record, trees in parks and on street sides still behind in blooming – except for Maggie Bourke-White’s lilacs. I wonder where she finds them? Bora neared his lips to the cup without drinking – the porcelain rim was hot enough to scald. Not even by leaning out could he be sure, but his car and driver must be waiting below. Or maybe not; it was still early. Four o’clock was when he’d asked for a shared cab to Leontyevsky Lane, where he was to join embassy undersecretary Manoschek, with whom he’d fly to German-occupied Poland. Unlike him, Manoschek was continuing west to Berlin.

It was good to have at last secured a room with a view after weeks of overlooking the hotel’s inner court. Bora searched the bristling horizon of cupolas, spires, towers, flat roofs of immense tenements; an odour of heating fuel and wood stoves lingered, factory smoke and smells, mostly the pungent aroma from the state brandy maker at the other end of the block. About now, from Dzerzhinsky Street’s GPU offices, so inconspicuously as to be suspect, a sombre car was no doubt approaching the National. Without smiling, Bora was amused. Are Max and Moritz in it? I bet they are; I threw those cartoon characters out of bed. There’s never a time that I walk from here to the embassy without being shadowed by one or the other, or both: all I can do is go out of my way to leave early and take the longest route possible, down to Spasopeskovskaya Square and Steinhardt’s federal-style residence, or all around the Kremlin, crossing and recrossing the bridges before heading again for the Garden Ring. I hardly stop anywhere, take no photos, so they can’t very well find fault with me. At most, I slow down in front of bookshops, or the Bolshoi Theatre (under repair), or the costly delicatessen stores on Gorky Boulevard. In the end, the few hundred metres from the National to our embassy swell to two or three miles. I make my shadows earn their daily bread.

Again he brought the cup to his mouth and took a sip. Immediately the thought “Coffee has a strange taste” bolted through him. Bora, who drank it black and never stirred it, rushed back to the middle of the room, reached for the spoon on the silvered tray and scooped up some liquid from the bottom of the demitasse. He fished out a grainy residue, translucent, amber-coloured. His alarm rose like a spring released. With the tip of his tongue he tasted the particles from the spoon, a small motion that relaxed him at once. Nothing but sugar. Cane sugar, expensive in Moscow – an unrequested, additional touch for the foreign guest at ninety-six rubles a night. Why, on my monthly pay I couldn’t afford to spend more than ten days here: of course they’d sugar my room-service coffee. And they wouldn’t be so crass as to poison me with breakfast.

Bora drained the cup, feeling foolish, but only to a point. It isn’t here that I’ve learnt to keep constantly on the alert: here I’ve perfected the lesson. Is it excessive prudence never to let my diary out of my sight, even placing it inside a waterproof bag when I shower? Staying in Moscow makes you paranoid. Again facing the window, without need of a mirror he deftly looped the silver cord aiguillette over his right shoulder, secured it to the small horn fastener under the shoulder strap, and hooked its end loops to the tunic’s second and third button. Below, Gorky Boulevard was in a suspended state between sleep and stirring to life. His late father had known it as Tverskaya, before the house fronts were moved back to double its width, when stores had rich pediments and wooden signs, and long rows of hansom cabs lined it. Today it was a channel for delivery trucks, early buses, “shared cabs”, people heading for an early work shift. Bora buckled his belt. Moscow would do without him today, and vice versa.

On the bed, his bag contained no more than was needed for a three-day trip. Glancing at it, it was impossible not to think of his other luggage, ready and waiting in East Prussia. But Bora had learnt during this assignment to bridle these and other thoughts, so he immediately shifted the focus of his attention. He no longer surprised himself at his ability to hide his own thoughts from himself, as if people around him could read his mind. So he kept from thinking “East Prussia”, telling himself “Russia” instead of “East Prussia”, and “diplomatic service” instead of “First Cavalry Division, ready to be deployed”.

Lavrenti Pavlovich’s note in his pocket felt like something that could spy on him just by being in contact with his body. Bora took it out and contemplated it. Dafni, Mandilaria. Cretan place names? Does the first suggest a wine with the flavour of bay leaf? Dafni means laurel in Greek. They all drink loads, these Russians, from top to bottom. What generals are left over after the Purge swim in alcohol; 35,000 officers push up daisies instead.

Of all the mundane incumbencies typical of serving in an embassy, a round trip just short of 3,500 miles to fetch wine was nearly mortifying at this time. Manoschek had gone to Germany for a routine visit, but who knew what his true intentions were. He might be carrying documents to be removed in view of the attack against Russia. Between now and then Germans in Moscow would ride to work, buy cheese and champagne on Gorky, attend parties where refusing repeated toasts was out of the question. Bora closed the window. He was aware how, now that Krebs substituted for the ailing General Köstring, the presence of Schulenburg, Krebs and himself justified the Foreign Minister’s mocking definition of the embassy as that nest of Saxons. Not a criticism, but not a compliment, either. Bora would go out of his way not to show disappointment over this errand.

Minutes before four o’clock he was packed and ready. He set his empty cup and tray outside his door and the overnight bag as well, unlocked. It simplified the business of the Russians looking through it, despite all passes and permits. At airports and railway stations you knew they’d already gone through your things when customs agents magnanimously let you pass without checking. Diplomatic privileges seldom applied to lesser representatives of the Reich, and least of all to their luggage. Even the Ambassador’s suitcases had been stopped once. It had taken outraged telephone calls to disentangle matters and caused a paralysis of all trains until a special convoy delivered the sequestered goods. So Bora travelled light, and readily said what he knew customs officials expected him to say.

Surveillance he was used to. When he and his brother were growing up, their rooms had no key, because his general-rank stepfather did not allow the boys to lock themselves in.

Truth be told, Bora secretly contrived to make a skeleton key. He never made use of it: it was enough for him to know he could lock himself in if he wanted to. There were nights when he slept on the floor so that on first inspection his stepfather would think him gone; other nights he simply sat up in bed, thinking. At twelve, thanks to the skeleton key, he’d already laid his hands on most of the forbidden books, kept in a small panelled room next to the library. He didn’t necessarily read them: he was satisfied with having bypassed prohibitions. Still, he rarely lied: asked directly, he’d answer with the truth. To his younger brother, he confided all but those things that might force him to lie as well. I am responsible for my silences and my transgressions, he told himself, and cannot involve Peter in them.

The story of the skeleton key remained a secret to everyone. Bora even took it with him to Spain, only to lose it during the bloody siege of Belchite. That was in ’38, and ever since he had felt as though he’d lost part of his private world, as if anybody (who, in the immensity of a land torn by civil war?) could, on finding it, gain access to his most secret self. Stepping out of the hotel room, Bora had to admit how the same desire to protect himself and remain ultimately inaccessible had brought him to volunteer for counter-intelligence. Discipline, self-control, firmness – the qualities his superiors praised in him – matched the unlockable door of his childhood. Bora, however, kept an imaginary key on the side: I consider myself free to do what I must. The sole difference was that now he’d do so even at the cost of shamelessly lying.

In the hallway, the flowery scent from the Caldwells’ room wafted to him. Bora caught sight of a forsaken, small sprig of lilac on the lift floor, a blooming tip of tender pink. He retrieved it before someone had a chance of stepping on it, careful to tuck it out of sight inside his cuff before reaching the ground floor.

I’ll give it back to her when I see her again.

He left the key at the desk and picked up the daily papers. The cream-coloured nude statues buttressing the archway – half demigods, half Saint Sebastian – looked down as he crossed the deserted lobby. Outside, barely short of a cold drizzle, suspended particles enveloped him as he left the multi-storey turn-of-the-century leviathan. The cab, a marshrutka limousine usually shared by several passengers but this morning reserved for him exclusively, waited along the roadside. Naturally, so did Max and Moritz, across the pavement in their black ZIS, parked toward Hunters’ Row.

In two minutes 600 or so metres were covered. The driver – actually a low-rank NKVD operative who called himself Tribuk – turned left at City Hall and followed the back streets to the German Embassy, so he wouldn’t have to turn around to continue to the airport. Being tailed had its rules.

Rain began to fall. Standing under what protection the balcony above the entrance afforded him, the undersecretary waited in a dark trench coat, with two brass-cornered suitcases at his feet. Bora left the car to greet him, and he drawled a lethargic reply to the military salute. “Morning, Rittmeister.”

“Good morning, Undersecretary.”

“What, no greatcoat?”

“No.”

“Sort of cold not to wear one.” Manoschek had a gift for stating the obvious. Bora was in fact uncomfortable, but it would be an encumbrance to take along extra clothing for the Mediterranean. He watched the official reach inside his breast pocket. Still bearing the marks of the pillow on his right cheek, he looked as though he could do with some more rest. “Mail flew in for you, Bora.”

“Thank you.”

Motionless while the driver busied himself loading the suitcases into the car, Manoschek commented, “It appears you’re friends with the Chancellor of Freiburg University.”

“Professor Heidegger?” Indifferently, Bora reached for the envelopes. “I’m not friends with him, I took his pre-Socratics summer course back in ’32.”

“He’s under surveillance, you’re aware.”

“Has been for the past five years.” Bora turned his eyes to the two men inside the idling ZIS and resolved to show no haste to review the mail. “Why do you think I correspond with him?”

It wasn’t true. Or it wasn’t true in the sense that Bora’s messages to the philosopher were part of the close observation – the Gestapo took care of that. Their last exchange had been on the scarcely seditious question of “appearance as a privative modification of phenomenon.” Seeing that Heidegger’s reply had been unsealed, Bora directly put the envelope away, and did the same with the rest of the correspondence from his family, including his brother Peter.

Manoschek wasn’t usually aggressive. But he’d drunk too much at the reception the night before, and his sternness served as a foil to embarrassment. He had a boyish face with a button nose; only an incipient double chin lent maturity to his profile as he glanced toward the east end of the lane and the incoming car. “All right,” he said then. “My angels are here, we can go.” They climbed into the back of the cab from opposite sides, with Manoschek’s briefcase between them.

“Care to see the newspapers, Undersecretary?”

The dailies passed from Bora to Manoschek, who at once unfolded them so it would be clear to the driver that nothing was hidden inside the bundle. As soon as the cab moved, Max and Moritz followed, and so did the newcomers who shadowed the undersecretary. The trio of automobiles regained Gorky and made north for Pushkin Square.

Manoschek ran his eyes across the paper spread on his knees. Was he reading, or simply avoiding the idle talk one always resorted to in the presence of Russians? That he waited at the embassy, while he roomed at the Moskva Hotel, could only mean he’d stopped by for documents to take along, certainly not Bora’s mail. When a small paper-bound book materialized in his hand – it must have been bothering him in his coat pocket as he sat – Bora succeeded in glimpsing its title before it sank out of sight inside the briefcase.

The Dead Live! Ah, yes, Manoschek relished occult literature. What else did he read he didn’t want people to know about? Bora contemplated the string of government buildings sliding past in the rain. At the second-hand book stalls on Kuznetsky Bridge Street I bought for 30 kopecks (less than 25 pfennig) a book I never expected to find in Moscow: Joyce’s Ulysses – in the German translation no less, published when it was already banned in its homeland. Has someone from our embassy (it could be Manoschek) disposed of a supposedly obscene, uncomfortable novel with a Jewish protagonist? All I know is that two years ago Wegner, up in Hamburg, beat the Bora Verlag to it (or else Grandfather decided against acquiring it). Whatever, I couldn’t pass it up. It’s been sitting inside my overnight bag in a plain brown jacket, as I don’t care to advertise that I have it and haven’t got time to begin it. But now, as I head for the Aegean, somehow possessing a book about the ultimate Wanderer of Greek myth makes sense.

Manoschek put away the newspaper. He asked, “Do you know by heart how to make a Beacon cocktail?”

“I don’t. I know it’s got egg yolk and chartreuse in it.”

“And brandy?”

“Maybe. Question is, in what proportions?” To get back at him for the Heidegger quip, Bora observed, “I try to stay away from cocktails, especially these fly-by-night imitations of American drinks.”

“I’d think you an expert, given your familiarity with foreign wines,” Manoschek sneered, but he wasn’t seeking a fight. Bora ignored him. He met Tribuk’s pale eyes in the rear-view mirror, and chose to wrong-foot him by staring back.

They reached and crossed Mayakovsky Square. Trees battered by the recent hailstorm stood over carpets of shredded green leaves and branches. It was here that Bora had turned to drive past the forbidden city house of Lavrenti Pavlovich. The habit of hiding his thoughts had become second nature. He was careful not to glance left, where the Lenin Military Political Academy occupied half a city block, but in this capital of ministries and barracks you’d have to shut your eyes to remain uninvolved. From here on, especially once past the Baltic and Byelorussia Station, offices connected to commercial aviation and aeroplane factories followed one another. It would be Leningrad Boulevard by then, leading out of Moscow.

Shortly before five o’clock they reached Tuschino. The airport, beyond a narrow canal, filled the oblong space in an oxbow of the River Skhodnya. Water fowl, haze rising from the water, seclusion – one could imagine it as the military camp it had been 400 years earlier, in the “Time of Troubles” that bloodied sixteenth-century Russia. Czar Boris Godunov had just died then, the second False Dimitri had allied himself with the Poles and Jesuits. Manoschek was no lover of Russian music; no point in Bora mentioning Mussorgsky’s opera on the subject.

With Max, Moritz and the two angels stationed outside, the Germans walked into the terminal. Neither of them anticipated obstacles; all details of their respective destinations had been cleared beforehand. Somehow, however, even leaving Russia with the blessing of the authorities could be difficult. Bags were opened and inspected by a uniformed official (brick-red collar tabs, which meant NKVD), who stopped short of frisking them but made an issue out of an unreadable signature on the permits. It meant a round of phone calls understandably complicated by the early hour. Even on Monday, most offices in Moscow would still be closed. Within minutes, Manoschek, who relied on Bora’s knowledge of Russian for his recriminations, was visibly checking his temper to avoid incidents. Only a pink flush in his face revealed his state of mind. As a result, the sleep mark on his cheek stood out like a scar, while on the other side of the counter the Russian stayed stone-faced, with the handset glued to his ear.

Bora refused to become emotionally involved at this early stage of his errand. He was thinking of the scene in Boris Godunov (his father, the Maestro, had directed Chaliapin in the lead role), when the enraged Czar is told Dimitri threatens Russia from the west: “Let nothing through, not even a soul from the border: not a hare from Poland, not a crow from Krakow!” How fitting, all considered. A silent consideration escaped his mental censorship: Forget hares and crows, there will be German eagles invading soon from Poland.

Comrade “Tichomirov, Yegory Yosifomich” seemed the hardest to get on the line, being out of town – still at his country dacha, most likely. Manoschek fretted. Bora chose to walk to the window overlooking the runway. When a handsome Lisinov twin-engine came into view, leisurely taxiing as it awaited permission to take off, he inwardly lit up. A welcome sight, for a change: if authorization to leave was ever granted, the socialist version of the DC-3 promised to offer the most comfortable leg of the journey.

It was 6.30 before the snag was resolved. On cue, the shared taxi and the two ZIS left together, and the NKVD official strode to unlock the door to the tarmac. “Dobrogo puty” was called for, but he kept from wishing the travellers a safe journey, or adding anything to that effect. Whether or not the Germans would agree to separate from their luggage, no one offered to carry it for them. Manoschek stormed out of the building ahead of Bora. “Hell,” he said through his teeth as he swung the brass-cornered suitcases, “having to sweat blood for the privilege of travelling 1,000 miles on Russian wings.”

Bora caught up with him. “American wings, really, regrettably with a higher range than our best bomber to date.” On this side of a smile, he added, “It beats an eighteen-hour train ride to Warsaw any day.”

On the rain-wet, silver sheen of the fuselage, elegant cursive letters spelt in red City of Moscow. Overkill though it was, the attendant at the foot of the ladder double-checked the passengers’ papers before letting them on board.

Once up in the air, through the drizzle the spires of a large reddish church wheeled slowly below; fat green meadows, the houses of Krasnogorsk on the Moskva. A fearless climb followed, bucking and bumping through a layer of low cloud into a blinding sunbeam, only to reach the ragged vapours drifting above. Surely designed as transportation for high officials, the plane’s interior was provided with all manner of comforts, and the two Germans had it all to themselves. Drinks were made available to them – tea, mineral water, Gollansky gin in sealed bottles. Manoschek refused to touch anything; Bora, ever since the night of his errand under orders to follow prophylaxis against malaria, took Atebrin with a glass of water.

Before long, the undersecretary was deep in his book on the occult. Too deep, maybe, because he eventually dozed off in the comfortable seat with his forefinger stuck as a bookmark between pages. On the opposite side of the aisle, Bora went through his correspondence and the newspapers (his hunting ground for useful titbits slipped through censorship). Heidegger had attached to his reply a recent essay on Hölderlin’s Greek poetry, and how “this essence of sea travellers, lonely and feisty” should not be confused “with every seagoing trip”. Der Nordost wehet, read the poem, “The nor’easter blows”. Relevant somehow, punctual somehow, like Joyce’s Ulysses in his bag. In the four and a half hours of flight the two men exchanged no more than a few sentences, which was just as well, since – for all they knew – official aircraft were bugged even as their hotel rooms were.

Eventually, the immense Pripet Marshes created a broken patchwork of dark greenery and wide pools below; marking Poland’s Soviet-occupied east, water alternately dazzled as it reflected the sun or grew sombre as it became overcast, like a great musky creature whose many eyes blinked open and shut. Bora put away the papers. The view of the marshland quickened his pulse. I may soon be riding through it with my men, he thought. Smiles, diplomacy, slyly tossing alcohol in the flowerpots to avoid overdrinking, careful not to offend our hosts, meanwhile… It’s all in preparation for our real plans.

Lublin was the first landing field over the border of the German occupation zone, on a plain dotted with round lakes. As the Lisinov drew near, two Luftwaffe fighters assigned to the airport took off to meet it. Bora had crossed the area in ’39; he recognized the winding course of the Bistritza, the city slaughterhouse on the side of the road. In those days the airfield had suffered bomb damage; repairs were proceeding at a feverish pace.

Under escort, the City of Moscow banked widely to the south, approaching the runway with a tail wind. Manoschek put away the book, yawned into his fist and looked over. On the starboard side, beneath the broken clouds, the roofs of the Majdan Tatarsky labour sheds grew visible, then slid past. “What’s that?” he enquired.

Bora bit his tongue. “Clothing works.”

What had Heidegger written to him? It’s all in freeing oneself from a concept of truth understood as concordance. Which meant he could answer “Clothing works” (the undersecretary not being a confidant of his, and the Russians perhaps eavesdropping) when Little Majdan, Majdanek, was well on its way to becoming a concentration camp.

On the ground, a spartan Ju-52 was refuelling. It was Bora’s, not Manoschek’s. The junior diplomat, with extended stopover time, welcomed the chance to get lunch. An orderly took charge of his suitcases, allowing him to head without encumbrances for the mess hall.

“See you in Moscow, Rittmeister,” he said.

Will not, Bora told himself. You’re out of Russia for good, as we prune our embassy staff of non-essentials. “See you in Moscow,” he replied sociably all the same. A few minutes after eleven, Moscow time; ten locally. The half hour needed for the cargo plane to be ready could allow him to get a bite to eat, but Bora didn’t care to prolong his association with Manoschek. He set back his watch one hour and waited, pacing around in the chill of day.

The southerly that compelled the Russian pilot to modify his landing became a headwind as Bora continued to Bucharest. The expected three and a half hours in the air became four, worryingly close to maximum range. Bora, the only passenger among crates of various supplies, leafed through Joyce’s novel so as not to stare at the co-pilot’s nervous tapping on the fuel gauge. At 14.48, in the lashing rain, the slippery runway of Baneasa airport felt pleasant under the tyres of the landing gear. It turned out it wasn’t the fuel gauge the co-pilot was knocking into reaction, but some other indicator. “Won’t be continuing for another hour, Rittmeister, maybe two. If you don’t suffer from air sickness, you’d better eat; it’ll be evening before we get to Athens.” Bora did as suggested. A kind of stolidity set in whenever he couldn’t appreciably modify his lot. Suspended between north and south, winter and summer, peace and war, he did what was strictly needed, saving energy. An indifferent plate of food and bottled water would bridge him over to Greece, and to an indifferent bed. Tomorrow, Crete. Day after tomorrow, back to Russia. He could nearly see himself from the outside at times like this, moving about or standing still. His thoughts, his censored thoughts became transparent then; there was no hiding them, or from them, or from himself. He padded layers of extraneous ideas over those thoughts, for safety. He ate alone in the mess hall of the Romanian Air Force. With nothing to read but dailies already gone through and the politically dubious Joyce novel, Bora searched his memory for Greek words to use in Iraklion, as if ancient Greek would avail him at all. The sole quotation that came to mind from his schooldays began Essetai e eos e deile… something-and-something. The Odyssey, maybe. Ulysses had travelled much less conveniently than modern man, for ten full years. More: he did ten years of war plus ten years of wandering, before making it back to his home, such as it was. Essetai he heos… “A dawn will come”: who the hell says that?

It was 450 plus miles to Athens. The Junkers left Bucharest shortly after four, in heavy rainfall. When they reached the Danube, the weather cleared unexpectedly, as if the world were turning a page. Mountains, plateaus, eventually the distant blue of the sea: another dimension opened, where the afternoon grew increasingly bright. Bora reached Athens around eight in the evening, drowsy but not at all tired despite the long journey. Essetai he heos he deile: those few Greek verses rolled in his recollection as he dozed off.

TUESDAY 3 JUNE, 6.36 A.M., ATHENS, GREECE

It was impossible or too early to say whether the day would be sunny. Mist rolled in from the sea when Bora reached the harbour and climbed into the rowing boat that would deliver him to the plane. The mode of transportation for the final leg was an ambulance Junkers, an “Auntie Ju” marked by a red cross and equipped with floats. Its crew, making back for Crete after delivering to the city infirmaries German paratroopers injured in the fierce days of fighting, agreed to take Bora only on account of his higher orders.

That the conquest of the island had been a bloodbath, Bora knew from unofficial embassy reports. Sporadic enemy resistance in the hinterland still posed a major danger and would continue to do so. Nonetheless (or because of it), army reporters and photographers were flooding in to present it as a resounding success: after all, the Brits and Colonials had been roundly beaten, losing lives, equipment and vessels in their flight.

Ahead of Bora, the medical personnel had already taken their places on board. He saluted and was at once the focus of their attention; his own, acutely aware of more disturbing odours under the whiff of disinfectant, plunged him for a moment back to Krakow nearly two years earlier, when he’d stared at colleagues torn to shreds in a grenade attack. Nurses, medics, a surgeon, all cramped in the facing rows of stretchers that replaced the seats, were clearly wondering who he was.

There was nothing to be done. Feeling more out of place than ever before in his life, Bora had the choice between taking the last corner available on the backmost stretcher or trying to balance on his feet for the next two hours. Dignity won over comfort, and he sat down cramped, hoping to be ignored. The surgeon, however, scowled at him above his metal-rimmed glasses; the nurses gawked (one was pretty, with the upturned nose of a small dog, the others very plain and sunburnt). When the co-pilot made a last round before locking the door for take-off, the surgeon asked him directly, “Who’s the decorative young buck?”

It had been unfeasible to secure tropical wear in Athens. Bora was still wearing his embassy gear, so the comment was justified. The co-pilot leaned over to answer something.

“He’s going to Crete to do what?” the surgeon remarked loudly enough to be heard by all. Well, he would say that. Four thousand German casualties, whose blood and vomit were still staining Crete’s rocks and polluting the air inside this plane, and this spit-and-polish intruder was travelling there to procure cases of wine. Bora inwardly blushed at the words. A sudden urge, very much like a yearning to suffer in order to be somehow worthy, washed over him; whether his reaction was resentful, childish or both, the surgeon’s insult did not sting any less because of it.

No one addressed him during the flight, too bumpy for seeking refuge in reading, much less writing. Before the floats touched the water of Iraklion harbour, Bora unhooked the silver cord aiguillette from the buttons and from under his shoulder strap, slipped it off from around his right arm and put it away.

Essetai he heor he deile he meson hemar… The rest of the verses came back to him as the Junkers bounced and lifted great waves of spray to a rolling halt.

“A dawn will come, an evening, a midday when someone will bereave me of life in battle by the stroke of a spear or a bow’s arrow.”

Godlike, fair Achilles had spoken them, prophesying his own death as he readied to plunge his weapon into Hector’s throat.

2

3 JUNE, 8.25 A.M., IRAKLION, NORTH COAST OF CENTRAL CRETE

The splendour of daylight pointed to a place that seemed nothing but a German depot. The harbour was piled with materiel. Bomb-damaged, being cleared now of rubble, the dock lay cluttered with carcasses of fishing boats blown out of the water, sails, masts, oars, crates, containers of all kinds. End to end, three sand-coloured, diminutive Italian cars one could barely fit into reclined on their sides like a disjointed, broken toy train. A British truck and a German tracked kettenrad sat parked next to each other under a veil of dust as if they’d been there for years instead of days, or hours. No wind, only powdery stuff still coming down after the air raids and battle. Along the breakwater seagulls picked at floating litter, wary about nearing the shore.

A battered bus with a red cross painted on it idled in the confusion. Surgeon and nurses filed towards it, climbed aboard, were gone. Bora – whose orders were to stay there until his contact arrived – watched, shielding his eyes, as it clattered to town. Sea odours, war odours were strong; the light was strongest of all. June days might be endless in Moscow, but being dropped into this southern light was excessive, like regaining one’s eyesight after an extended period of blindness. Two and a half hours south-east of Athens, the muted skies of the north seemed never to have existed. All appeared bright yellow to him. Yet from the air he’d seen green patches besieging the bony spine of the island; he’d seen and recognized the great saddleback of Mount Ida, but also squares of silver-green, olive groves and fields.

From where he stood, the town of Iraklion was difficult to judge. A squat fortress nearby jutted out to sea. Beyond, Bora made out a crowd of mostly two-storey buildings, gaps that marked narrow streets or demolished roofs. He imagined an atmosphere halfway between a Middle Eastern bazaar and an Italian piazza; given Crete’s past under Ottoman and Venetian rule, both applied. Around him, only German soldiers were in sight, and heavy equipment that forced him to stay out of the way. Among the makeshift directions to this or that command post, nailed or glued to their Greek counterparts, a sign to his right read, “Look out: live high-tension wires.” Bora picked his way carefully along as he reached the low wall bordering the wharf, because being electrocuted while requisitioning wine in Crete was not among his plans for the war.

The name of the contact he’d been given in Athens – a Major Emil Busch, German Twelfth Army Abwehr – surprised him given the modesty of his errand, particularly in a place where Air Force Intelligence was expected to serve. Standing where he’d be visible (and all too recognizable in his winter uniform), Bora had no doubt his man was on his way now.

Formerly attached to the DAK (Deutsches Afrika Korps), Busch looked every inch the part: pith helmet, colonial tunic, khaki shirt and tie, canvas top boots tied from knee to ankle. He seemed to have taken along the colours of the desert sand; the whites of his eyes, too, made dingy by the long-term use of anti-malaria drugs. They acknowledged each other routinely.

“How was your trip?”

Bora shook the outstretched hand. “Fine, sir, thank you.”

“A bit long, I’ll bet.”

A raised left eyebrow, as if an invisible monocle kept it up, gave Busch a perplexed or critical glance; his voice, however, expressed nothing but formal solicitude. It did not call for a reply, all the more since Bora didn’t feel tired at all. Only overwhelmed by the light. “I’m ready to proceed with the assignment, Herr Major. The pilot informed me there’s a cargo plane leaving tomorrow at seven. I expect to be on it with the shipment.”

On Busch’s part, a small delay followed. Less than hesitation, more than an accidental pause. Bora had the distinct impression the interval meant, “That may not be possible”, which was odd, since the major had said nothing of the kind. It was just that pause, like a shadow that flits by and leaves nothing behind. From the level of the harbour, Busch led the way towards a tall, modern building on a rise just inland, along a street facing the sea. His gait was slightly off, the left leg pivoted a little outward, drawing a quick half-circle as it took the next step. He spoke up over the harbour noises. “You’ll recognize the Megaron. Five floors of hotel frequented by the best society in peacetime.” He glanced over his shoulder, “By the way, when were you here last?”

“It’s my first time, Herr Major.”

“I understood it wasn’t.”

This too sounded strange. What difference did it make? Bora decided not to read more than there was into Busch’s nonplussed words. “Perhaps because Grandfather Franz August served as vice-consul in Chanià earlier in his career. My mother spent some years here as a child.”

“You don’t know Crete, then.”

“Not at all. I’ve only seen old photos of my grandparents’ residence at the western tip of the island.”

“Hm.” At the entrance of the hotel Busch raised his hand in a half-wave, less than a military greeting, in reply to the guards’ salute. “That won’t help.”

Ah-ha. This was more concrete than a pause. Bora followed, glad to get out from under the sun. “Forgive me, but why would I need to be familiar with Crete? I only have to pick up those confounded bottles and wait for the next flight out.”

Instantly, and for a moment more, stepping indoors from the blaze of the harbour seemed cool darkness itself. Busch was standing in it, at the centre of a devastated lobby. “…You did, until this morning.”

“I only arrived this morning!”

The major summoned him closer. His movements were small, controlled to the extreme, a habit of working in the heat: lifting his forefinger and hooking its tip once or twice did it. “Something came up, Rittmeister.” In a lower voice, he added, “You can tell by looking around – I’m sure you saw the state of the harbour from the air – that the last two weeks have not been a picnic. In the middle of all this, counter-intelligence is in the political doghouse. As if our preliminary reports that the locals are fiercely independent meant they’d dislike the Brits and love us.”

Underestimating enemy numbers sounded more like it. Bora only said, “It’s obvious there was no red carpet waiting.”

“Right.” Busch inhaled noisily. Although only around forty, he had one of those faces that wrinkle up entirely and age years when grimacing. “I’d rather say no more about it. Follow me, please.” Something came up. From habit, Bora didn’t solicit details when orders were concerned.

Clearly, they’d changed since his departure from Moscow. How, where, by whom, he might or might not be told. They couldn’t be worse or less useful than those he presently had, so he kept his mouth shut waiting for more. One step behind Busch, he crossed the lobby between piles of broken window glass, trying not to think ahead. Compared with Russia, the heat was brutal. He’d reconciled himself to winging it for twenty-four to thirty-six hours in his Moscow uniform, and having it laundered as soon as he returned to the National. Now…

“You’ll have to secure tropical gear.” Busch seemed to read his mind. “You can’t trek around in riding boots.”

Trek around? Again, Bora said nothing. They had meanwhile stepped into a large room, a breakfast or dining space freed of tables. Photographs of the Greek royals, taken down from the wall, sat propped up on the floor – a sad-mugged king who’d spent half of his life with the crown in his suitcase, and a childless Bulgarian queen with plenty of lovers. A stack of coffee cups crowded a sideboard. Some clean and bone-white, most of them dirty, they let out a whiff of strong coffee as Bora went past. Sturdy brew, Turkish-style, memories of Morocco and the Spanish Foreign Legion. Either left behind by guests fleeing in haste, or used by troops of one or the other army, that forsaken porcelain heap implied even more than the downed royal portraits.

Busch reached a desk (the hotel manager’s?) near the far wall. Crowded with folders, and now topped by the discarded pith helmet, a huge mirror to its right reflected it, opposite a window just as large and paneless, also reflected. Two desks and two Emil Busches, bathed in a pool of splendour by the doubled, unmerciful daylight.

Once he had removed his visored cap, Bora blinked in the glare. Something came up. He experienced something just below excitement, a physical unrest on the verge of becoming elation. He thought of Herr Cziffra in Aragon, or Colonel Kitzel in his own hometown, Leipzig: a brand of officers like Busch, who had for the past four years got him in as much trouble as they had kicked him into growing up. Outwardly, he waited without showing any reaction other than to the excess of light. When he estimated that no spontaneous explanations were forthcoming, he only asked, “Where may I secure what I need?”

Busch squinted as he looked up from the desk, as did his mirrored twin. It would have sufficed to pull a curtain across the window or remove the mirror to diminish the glare, but clearly he liked it this way, or used it to unsettle his interlocutors. “Maps I can give you.” He took a lengthy sip from one of several bottles of Afri-Cola set on the floor near his chair. “Do you by any chance read Italian?”

“Yes.”

“Here you go, then.” A handful of folded charts came Bora’s way. “Clothing won’t be easy just at this moment – you’re tall, too.”

“And I’m not Luftwaffe.”

The half-empty cola bottle – pinched in the middle, with the relief of palm trees on the neck – balanced on the one corner of the desk that was free of papers. “You might have to mix and match. As long as you have the right headgear and insignia… There’s a deposit of English tropical uniforms down the street.” Busch scribbled on a piece of paper with the hotel letterhead. “See what you can find there.”

Bora skimmed and pocketed the note, as he’d done with Deputy Chairman Beria’s. “May I know what my orders are?”

“Oh, sure.” The major reached for the bottle. He tilted it more and more as he emptied its bubbly contents to the last. “You must have been wondering.” Again that snorting intake of air and a tight-lipped stretching of lips that expressed more discomfort than amusement. A manila envelope was retrieved from the pile. Out of it Busch pulled photo enlargements and a folder marked Ampelokastro, eyes only.

One at a time, one on top of the other, the photographs were laid so that Bora could glimpse them against the confusion of papers. “And here’s the full report, to be read with utmost care. We need answers before the International Red Cross intervenes or Reichskommissar Himmler sends someone, and without stepping on the toes of the airborne troops too much. They’re foaming at the mouth. How about a cola?”

“No, thank you.”

“You should be drinking lots in this weather. I learnt it after getting sunstroke in Egypt. Nerò is water, metallikò nerò is mineral water, which you should always ask for. As I was saying, our paratroopers have seen their comrades riddled with bullets as they came down or got caught in tree branches; there’s talk of torture and mutilations of those who fell into enemy hands, especially the Greeks’. I assure you, the airborne troops aren’t keen on anything Greek at present, and you can’t blame them.”

Without saying it out loud, Bora wondered what chance he had of finding support for an enquiry. Murdered civilians. Whatever it’s really about, things don’t look promising; it’ll be like pulling teeth. There’s little chance truth will be a question of concordance with events or anything else… Professor Heidegger notwithstanding. He chose not to peek inside the folder, possibly the only way to avoid having second thoughts. “How much time do I have? I’m expected back in Moscow.”

“We know where you’re really expected, Bora. But that’s three weeks away. Ambassador Count von der Schulenburg is au courant, to use diplomatic French. Colonel Krebs also, and though he isn’t at all happy about it, as if wine mattered more than risking an international incident with Switzerland, he lets you off your embassy hook for a week.” Busch replaced the empty bottle with a full one, which he opened and disposed of in one long gulp. Stiffness and protocol were not compatible with a belch, and in fact he amicably let go of both. “I’m going to take a leak now. Please review the stuff here and give it back. The photos you can keep, we’ve got copies. Goes without saying that by now it’s well beyond eyes only.” Halfway to the dining-hall door, he wagged his forefinger one centimetre either way. “And report back here when you’re done at the depot: there’s more to discuss. We’ll find you lodgings somewhere in this building.”

In the few minutes he was alone in the room, Bora read the physician’s extended report to the head of the 7th Airborne Division. When the major walked back in refreshed, drying his hands on a handkerchief, the folder had already been returned to the desk.

“Questions, Rittmeister?”

“I’ll have them when I report back, sir.”

“Good. Since you’ll want to get around independently from the Luftwaffe authorities, I’ll work on procuring you a local guide. Without one, you stand to have your head blown off within a mile of the city wall. Come, I’ll see you out and point you towards the depot.” In the lobby, where the wintry glitter of broken glass resembled and made him long for ice and anything cold, Busch did a sudden about-turn. “In other matters, not altogether unrelated, we lost the von Blücher boys, ‘Old Forwards’’ descendants, all in one day.”

Bora halted so as not to collide with the major. “Good God, the eldest was born three or four years after me. I doubt the youngest was out of secondary school.”