Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Bitter Lemon Press

- Kategorie: Abenteuer, Thriller, Horror

- Sprache: Englisch

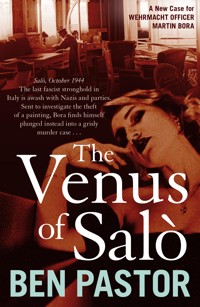

October 1944, in the Republic of Salò, a German puppet state in the north of Italy and the last fascist stronghold in the country. After months of ferocious fighting on the Gothic Line, Colonel Martin Bora of the Wehrmacht must investigate the theft of a precious painting of Venus by Titian, stolen with uncanny ease from a local residence. While Bora's inquiry proceeds among many difficulties, the discovery of three dead bodies throws an even more sinister light on the scene.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 541

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

3

THE VENUS OF SALÒ

Ben Pastor

CONTENTS

MAIN CHARACTERS

GERMANS

Martin-Heinz von Bora, Colonel in the German army

Lübbe-Braun, Bora’s second-in-command

Antonius Sohl, Lieutenant General in the German army

Klaus-Etzel Lipsky, Major in the German army, Sohl’s aide

Herbert Kappler, Lieutenant Colonel in the SS

Egon Sutor, Kappler’s adjutant

Eugen Dollmann, Colonel in the SS

Jacob Mengs, Gestapo agent

Albert Kesselring, Field Marshal in the German army

Karl Wolff, General in the SS

Zachariae, Mussolini’s private physician

ITALIANS

Giovanni Pozzi, textile industrialist

Anna Maria “Annie” Tedesco, his daughter

Walter Vittori, Pozzi’s brother-in-law

Rodolfo Graziani, Commander-in-Chief of the Italian Republican Army

Emilio Denzo di Galliano, Graziani’s aide

Gaetano De Rosa, Captain of the Republican National Guard

Cesare Vismara, Inspector in the Italian Police

Passaggeri, Inspector in the Italian Police

Moses Conforti, antiquarian and photographer7

Bianca Spagnoli, former music teacher

Marla Bruni, soprano

Fiorina Gariboldi, Marla Bruni’s maid

Miriam Romanò, seamstress

Xavier Cristomorto, freelance partisan leader

Vittorio and Italo, partisan leaders, moderate faction

J.V. Borghese, Commander, X MAS (10th Marine Infantry Division)8

GLOSSARY

Abwehr: The Third Reich’s military counter-espionage service

Albergo: Italian for “hotel”

Animo: Italian for “Have courage!”

Atarot: In the Jewish tradition, crown-shaped embellishments for the Torah scroll

Ausserkommando SS Mailand: SS Foreign Command, Milan

Bandengebiet: German for “bandit territory”

Bedenken Sie es: German for “Mind yourself”

Besamim: Tower-shaped spice and perfume boxes, in Jewish tradition

Brigadenführer: SS military rank, equivalent to the rank of army major

Casa del Fascio: Italian for “Fascist centre”

Commissario: Italian for “police inspector”

Daven: In Judaism, the back-and-forth motion of the torso during prayer

Drei Hundert Rosen: “Three Hundred Roses”, a popular German song

Durchgangslager: A transit camp for inmates and undesirables

Einsatzgruppen: Special SS units created to eliminate Jews, gypsies and political opponents in the occupied territories

Ganz genau: German for “good enough”

Generalleutnant: Lieutenant general, in German army and air force

Gnädige Frau: German for “kind lady”

Hauptsturmführer: SS military rank, equivalent to the rank of army captain

Kripo: Contraction of “Kriminalpolizei”, the German criminal police10

Luftwaffe: The German air force

Malachim ha-Maveth: Angels of Death, in the Jewish tradition

Obergruppenführer: A high rank in the SS, second only to Heinrich Himmler’s rank of Reichsführer

Obersturmbannführer: SS military rank, equivalent to the rank of army lieutenant colonel

Organization Todt: German civil and military engineering organization

Permesso: Italian for “May I…”

Pinkas: A ledger listing the principal events in a Jewish community

Platzkommandant: German title for the commander of a given area

Radiosender: German radio station

Reichsmarshall: Marshal of the Reich, the rank given to Hermann Göring

Reichsprotektor: Nazi governor of the Bohemia-Moravia protectorate in Czechoslovakia

Rimmonim: Silver finials decorating the staffs around which the Torah parchment is rolled

SD: Short for “Sicherheitsdienst”, the SS Secret Service

Shekinah: In Judaism, the spirit and actual presence of God

Shivviti: In Judaism, a small case containing a prayer scroll from the Psalms

Sipo: Contraction of “Sicherheitspolizei”, the Internal Security Police of the Third Reich

Si vergogni: Italian for “You should be ashamed of yourself!”

Soldatensender: German army radio

Spielcasino: German army entertainment hall

Standartenführer: Paramilitary rank in various Nazi organizations, equivalent to the rank of army colonel

Via, via: Italian for “Go, go!”

Wehrmacht: Official name of the German army, 1935–46

11

Venus smiles not in a house of tears.

shakespeare, Romeo and Juliet12

1

960TH GERMAN GRENADIER REGIMENT HQ NEAR MT CASSIO, SATURDAY, 14 OCTOBER 1944

The voice spoke Russian. It cut through the dark, slicing it like paper, and the shreds were not to mend again. Martin Bora did not want to open his eyes, did not want to know whether it was night or not, whether this was Russia or not. As with voices in dreams, the sounds seemed to be inside him – inside the dark within – not travelling to him from elsewhere. Surely, if he stretched, he’d feel the jagged top of the wall and mud cleaving to his boots, but he didn’t. Instead, he lay there on his back. He did not recall lying on his back when the Russian dogs smelled him and strained furiously at the leash.

There was no wall, no mud. And the voice was harsh, but no longer speaking Russian.

Darkness broke.

Bora opened his eyes. The blinding glare of a torch filled them, causing him to blink; no place in his skull was safe from it. He recoiled from the brightness without averting his face.

“Get up,” the voice said.

Something told him it was useless to seek the handgun at his bedside. Elbows propped on the mattress, Bora tried to make sense of things, much as one stumbles through spider webs, becoming tangled in their gummy wraiths. “What happened, what is it?”

14The flood of light waved aside, just enough for him to discern civilian clothes, a baggy overcoat. A hefty man, middle-aged, a beefy jaw unhinging to speak.

“Gestapo. Get up, Colonel von Bora.”

Bora stiffened across his shoulders. He was not awake enough to rally his wits, but enough to taste fear. Dog-tired, exhaustion overwhelmed him in bed despite the ever-present pain in his mutilated left wrist; he took penicillin and what not for it, but the injections hurt and he could not say they helped. So he stared into the glare, befuddled, resisting the temptation to ask, “What is the charge?” – a phrase that was second nature to all of them in those years. Instead, as he freed his legs from the quilts, he repeated, “What happened?”

The man said nothing. When Bora went to stand up and reach for his uniform across the chair, another figure flung his riding breeches at him from the dark.

“Get dressed.”

Many times, he’d wondered what he would feel at a moment like this. The truth was that formless panic took over everything else. This has to be Russia, he made himself think. Had better be. Red Army voices from the past were still inside him, speaking not so differently from the man before him. He heeded all of them, automatically.

The whiteness of his underwear exposed him, lean and briefly vulnerable: at once, he began to cover it up with the field grey of the uniform. He slipped into his breeches, laced them with one hand and was halfway through buckling his prosthesis when the army shirt flew at him. He donned that, too, pressured into fitting himself.

The glare stayed on him; that invisible someone else was now rummaging in his dresser. Bora heard the army footlocker slam shut. The shaft of light moved up as he stood buttoning his tunic. The army cap came his way, and he put it on.

15“What about my men?”

They shoved him forward, walked him through the dim silence of the small requisitioned house. “They know you’re leaving. Your things are packed.”

No sentry stood at his post by the front door. What appeared to be an unmarked, civilian car waited with the engine running. Under a sad drizzle, Bora was let into the back seat. The burly man sat down beside him; the other placed his footlocker in the trunk, and the car took off. Eyed furtively, the phosphorescent hands on his wristwatch read 11:04.

The mountain trail rolled bumpily under the wheels; it climbed at first, only to negotiate a zigzag of narrow bends before reaching what had to be the state highway. They were heading north, surely. Bora sat facing forward, although the dark in the car was nearly as solid as in his bedroom. Splintered trees and devastated farms must have been pitching and bobbing up like wrecks in that sea of darkness. Bora imagined them as they kept heading downhill. He was cold, fatigued, yet alert now and totally tense. In and out, he tried to breathe through his diaphragm to relax, but it was no use. Worse. As drowsiness left him, stabbing pangs started in his forearm, a rapid irreversible progression until it became a bloody pain. He folded his left arm against his chest and clutched his elbow, thumb and forefinger pressed hard against the sore flesh-covered bone. Trying to conceal his suffering, he felt the envelope inside his chest pocket – Nora Murphy’s note on Red Cross stationery, carried around unopened for a week before he decided to read it. If I have to die, he thought, it might as well be now that she tells me.

Without turning to the man at his side, he asked, “Where are we going?” And, having received no answer, he sullenly minded the twists and turns of the car. The river valley below, that much he knew, led to a fork in the road, west to Piacenza 16and east to Parma. The latter route eventually led to Germany. God always has mercy, she had written him. In His wisdom, He has seen to it that my unhoped-for present happiness … She did not say so exactly, but he understood she might have fallen pregnant: the side effect of victory toasts on her diplomat husband, in liberated Rome. I cannot be so bold as to pretend to know what the future holds in store for us, Colonel, but you must promise that you will, between now and then, open your heart to what other love may come your way. She had underlined other, not promise. It might mean something. He did not reread Nora’s message: only folded it along the crease, replaced it in its envelope and slipped it into the pocket over his heart. In time, everything makes sense. Losing his left hand to a grenade attack, the annulment of his marriage, that brief, impossible passion for a married woman. Even a sort of bittersweet solace for having no impediments, if love ever were an impediment to death.

Half an hour, one hour went by. Through the corner of his eye, Bora perceived the bulk of the man beside him; from the rustle of waterproof cloth, he knew he was reaching inside his trench coat. He held his breath until he perceived the pungent, medicinal aroma of a cough drop.

“May I know why I’m being spirited off?”

Again, no reply. The engine pitch changed as the car reached level ground. Now and then, they went around an obstacle or rode the shoulder. They gained speed, slowed down to a creep. A roadblock came up, and with it a dozen godforsaken right places for firing a bullet through his head. We shall dissolve into Nothing – Georg Heym’s poem came to his mind. We shall dissolve into Nothing – but he could not recall the lines that followed.

A damaged, near-illegible road sign went by – the outskirts of Parma, home to Army HQ 1008. Once again, from here they could go left or right, or ahead to the Po River and its 17war-ravaged bridges. He settled into his habit of self-control over pain and fear.

By and by, he realized they were indeed coming to the river, where by coincidence or design, docked to a wooden platform on the bank, an unsteady but workable ferry waited to carry them over. Then came a rough regaining of the road, in the eerie distant glimmer of an air raid God knows where on the horizon. Bombed-out villages, bleak detours, shortcuts through the fields and along canals. At every crossing, Bora tried to think of where the next SS or army headquarters might be. As far as he could tell, they kept heading north. He recognized the turn-off towards Brescia, home to three SS commands at least, and to Army HQ 1011. Still they kept going. Every so often, German soldiers or Italian guardsmen stopped them at checkpoints. Bora was thinking of a letter to his parents, whether he should have written one or would be allowed to write one. Whether there’d be time for it after all.

Three wordless hours and more went by, through the damp autumn night, a pitilessly long stretch of time to mull over his life and what lay ahead. At Montichiari Bora identified the last possible turn-off – to an airfield, Ghedi, from where he could be flown off to Germany – but still the car headed north. Sinking into his deepest layer of animal-like forbearance, he found a dull equidistance between resignation and fear.

If not Ghedi, or Brescia, was it the lake they were heading for? Lake Garda, of course. Yes, yes. They would soon seek the steep, narrow Garda shore. Barely visible hills floated on both sides of the car. A downhill stretch, followed by the bristle of shadowy cypresses and a series of curves where palm trees drew the fanciful outlines of exotic belvederes. The lake must be ahead; no, to the right. Below them, to the right. Despite his stoicism, Bora was startled when the car came to a stop by a blind wall, slightly at an angle.

18He didn’t move until they opened his door to let him out. It seemed forever, with the engine still running. Bora heard the trunk unlock, then the dull sound of his footlocker being dropped on the road. Both car doors slammed shut again.

By and by, he became aware of raindrops tapping the visor of his cap and the shoulder boards of his greatcoat. He smelled the lake, heard the sigh of branches under the rain. It was a swift, dizzy awakening, as from anaesthesia, one sense at a time. The car had gone. The faint sinking of tail-lights far into the night made him suddenly furious. A terrific anger worked its way up inside him at the idea that his anguish had been for nothing; that this was somehow routine army business. The physical urge to pummel somebody kept him there, breathing hard, until he came back to his self-control. Across the road, as far as he could make out in the now pelting rain, several cars sat head-to-tail in front of a garden gate. Barely visible against the glare of a front door ajar, a sentinel at the gate clicked his heels when Bora approached. A scent of wilted flowers and moist leaves came to his nostrils. And the sharp smell of a doused fire.

“What is this building, soldier?”

“Lieutenant General Sohl’s residence, sir.”

“The town?”

“Salò.”

Inside, the bright entryway seemed blinding after the dark. A blue-grey-clad orderly behind a desk sprang to his feet. “Colonel von Bora?” He stared at the papers handed to him. “Lieutenant General Sohl was expecting you tomorrow, sir.” Still, he promptly led him into the next room. The confusion of voices that met Bora’s entrance alerted him that he was neither the reason, nor the focus of it. Ignoring him, worried-looking air force non-coms left muddy tracks on the carpet as they milled about. A civilian with the frumpy air of a police 19official, swollen-eyed with sleep, the top button of his coat driven into the wrong hole, strained to hear somebody – an interpreter? – speaking of “thieves” and “Italian responsibilities”. Bora overheard an impatient “What?” from the doorway of a third room, a muffled grumble and, “He arrived at this hour?” It was, after all, barely three in the morning.

Wearing breeches and boots, but in his shirtsleeves, Lieutenant General Sohl walked over to see him. Tall and rotund, with a shaven head, he resembled the voracious monks you see painted on beer jugs. To Bora’s salute he replied, “I appreciate your zeal for the assignment, but we were expecting you tomorrow morning.” And because Bora enquired at once about his orders, he let show an edge of anxious spite. “You see, this is not a good time, Colonel. Be so good as to report here in the morning as scheduled. Hager, accompany the colonel to his hotel. Where is your luggage, Colonel?”

Bora resented the tone more than the dismissal. “Out there in the middle of the street, where it was dumped. General Sohl, I wonder if you are aware of the mode of my summons.”

“Tomorrow, Colonel: you’ll tell me all about it tomorrow.” Sohl motioned to the Italian police official to follow him, and turned away.

Just as Bora was leaving the building, a bearded old man in his pyjamas and overcoat was being unceremoniously dragged in from the rain.

Hager, this young but savvy man, was the sort of busybody who thrives in command posts, the sort from whom intelligence officers, as Bora knew well from experience, can learn all sorts of useful details. Driving him down a narrow street, the airman actually relished being prompted. “They threw a hand grenade over the garden’s back fence two hours ago. Yes, sir, it does happen occasionally, even here in town. We don’t pay much attention as long as it’s just noise and a spurt 20of flames. No damage to speak of, but in the commotion that followed a painting went missing. A large artwork, showing a naked girl in bed. The general is concerned, because the villa and its furnishings belong to Signor Pozzi, and he says there are bound to be complaints. The bearded old man? No, sir. He’s just a Jew, an art expert.”

They reached a small piazza with a war memorial, by a docking basin. “Albergo Metropoli,” Hager announced, coming to open the passenger’s door. A dank odour of wet gravel and drenched wood wafted in from the shore. Water made lush, sucking sounds, as if the invisible lake were turning its tongue in its mouth. The road was all a puddle, in which Bora’s boots sank to the ankle. His long-repressed anger blew its top a moment later in the hotel lobby, when they assigned him a corner room without a toilet. He had a German colleague thrown out of bed and dislodged at once from his suite, into which he, Bora, moved without even waiting for the other to retrieve his things.

SALÒ, SUNDAY, 15 OCTOBER 1944

Everything was there. Uniforms, handgun, books, letters. Maps, sketches. Snapshots. Condoms, aspirin. His briefcase. Two of the books had broken spines, but his cloth-bound diary was safe. Bora had already gone through his footlocker the night before, still giddy with relief at not having been arrested after all, or shot, but anxious to make sure his belongings were safe. That morning, as he shaved, the face in the mirror had its usual firm coolness; it looked rather dispassionate these days. On the reflecting surface, through a window rimmed with white tiles, the waterline glowed under a sunbeam. Lakes had never been Bora’s favourite places. And this lake, in particular. 21Strewn along its shores, resort towns had become Mussolini’s ministry seats, barracks and embassies, as if defeat – inevitable, six months away at most – could be delayed by forcing enemy planes to pick through hotels and luxurious private homes. A last resort, in every sense. The leftovers of Fascism circled slowly like suds in a drain, where everything gathers before being going down the pipe.

Yet Bora had slept soundly a few dreamless hours and awakened perfectly lucid. No more confusion over leaving his temporary command post or his regiment, bled white by the Allies but successful in holding every assigned position in the summer war. They hadn’t given up a single stronghold, a single machine-gun nest or inch of territory; Field Marshal Kesselring himself had ordered them to withdraw in the end. As for him, reassignment was a recurrent rude jab in the back, steering him this way and that and expecting him to stay the course. He had learned to accept it, striving grudgingly to do well. Time away from the front line seemed like a waste at the end of 1944, but what nook of northern Italy had not become a front line? You could be killed by a grenade in your backyard, or while shaving in cold water by the sink. Bora tried to convince himself of all that, quickly passing the razor blade around his mouth; and yet, away from his regiment, he felt like a scab fallen off an open wound.

Mirrors were a luxury up in the mountains, not to mention other items. As with his men, he’d done without. And only after God-awful weeks of fighting, forty-nine hours and twenty-two minutes from the moment he’d read Mrs Murphy’s note, he’d taken a sunburned and experienced army nurse to bed. All night they’d had sex with the proficiency of soldiers, without kissing, and in the morning had parted with a handshake. She’d asked for his shaving mirror, “as a souvenir, and because I need a mirror”. And that was the sole missing condom from 22the batch. She, the Nursing Corps officer, whatever her name was, came from Lake Constance. And now here he was on a lake, too. Through the open window, mist blurred the opposite shore, past the waterline glowing like a hot blade tempered in liquid. In the piazza below, the Great War memorial reminded him that in the past generation Italy had bitterly fought against Germany, and won.

Five minutes before eight, Hager led him through the main hallway of Lieutenant General Sohl’s residence. On the wall by the staircase, bright oil paintings and tapestries clashed with the French wallpaper, all copses, streamlets and coy shepherdesses.

“That’s where the picture was, Colonel.” Hager pointed to the top of the stairs, where a massive, empty, gilded frame sat on the floor against the panelling. Bora glanced at it, going past. In retrospect, the anxiety he experienced overnight had been as void and apparently as useless as this frame without a canvas.

Next, he was led into an overly warm studio, heavy with the smell of cigars. An army desk bearing the nameplate “Generalleutnant der Luftwaffe Anton v. P. Sohl” took up the middle of the floor. In the couple of minutes he had to wait, Bora took in the details. By now the Flemish tapestries – real? imitation? – were no doubt saturated with cigar smoke. Overhead, the Gothic tracery was beyond elegance, on the carved, artificial edge of bad taste. But it was the fireplace, source of that excessive warmth, that struck him disagreeably: as if there were some danger lurking there after all, when he’d had more than enough of danger and having to face it without flinching. The chimney-piece was a face, vast and angry, snake-haired, moustachioed, its wide mouth gaping red within an arc of stone fangs. A fiery furnace, the jaws of hell, the parched throat of a giant.

Sohl’s voice came from behind. “I chose this room because of it.” Cheroot in hand, he strode in, impeccably attired this 23morning. “It has … How to say? An unquenchable, insatiable quality about it. I call it the Moloch fireplace.”

Bora greeted him, and then – because the general stared – the mandatory Party greeting.

He’d never met Sohl in the past, and, as far as he knew, there were no air force units on the lake. But they proliferated elsewhere on Italian soil, carrying out their duties in their baggy trousers and rimless helmets. The general could be the highest-ranking German in Salò, or else the representative of Field Marshal Kesselring, himself an old aviator.

Sohl understood that Bora was about to enquire about his summons and raised a hand to keep him from it. When he chewed on his cigar, clearly British war loot from better days, his fleshy upper lip made him look toothless. “You aren’t the only one to have had a bad night, Colonel. More about that in a moment. However your summons was effected, we’ll both have to make allowances for it. Herr Mengs had been touring the mountains on official business and agreed to give you a lift.”

Bora believed none of it. His transfer orders might have been issued orally, but it hardly fell to the Gestapo to carry them, much less carry them out. “Sir, my understanding was that I should lead the regiment to Brescia for rest and refitting. May I view a written copy of my reassignment?”

“Ah! Did you not receive it?” Sohl picked up a sheet from his desk and pushed it towards him with the moist end of the cigar. “As you see, the military governor himself signed your orders.”

It did not reassure Bora seeing the signature of Karl Wolff, Himmler’s SS envoy and plenipotentiary in German-occupied northern Italy, on the document.

“Why the long face, Colonel? Thank God, good commanders who can fall at the head of their troops are still aplenty. Experienced liaison officers such as yourself are harder to come by, you will agree.”

24So, that was what it was about. Officially. Despite his own tension, Bora could tell that the general’s mind was elsewhere. Smiling covered up some private concern; his prattle acted as padding.

“You young colonels,” he was saying, “so mindful of your indispensability.” (The usual stupid comments, Bora thought. How many times had he heard them?) “You presume to know where you’re useful. Well, it’s wherever they send you. Riga has fallen; Tito’s partisans are pushing on to Belgrade. Would you be capable of stopping all that? Of course you wouldn’t.”

Bora’s sternness prompted Sohl to reach for and hand over to him a slim manilla envelope. “Details of the situation and your duties: read them before you leave. Your previous assignment … Mount Cassio, was it?”

“And the Cisa Pass before that. Although not with the Hermann Göring Division nor the Monterosa, much less the ‘mongols’.”

“So, no bad conscience regarding civilian casualties. Good for you. You got your five months of hand-to-hand combat, the sort of excitement you army commanders go in for. I hear Signal wants to write you up, with photos.” Was it the overnight grenade attack that troubled him? Bora watched Sohl mouth the cheroot nervously. He recalled his late brother’s contempt for “desk pilots” who crowded offices and high posts while flyers died by the thousand. Despite the warmth in the room, Sohl turned to the fireplace, rubbing his hands. “Anyhow, don’t feel guilty about a liaison job. We’re not in Rome. No society ladies and no embassy cocktail parties, except maybe Herr Hidaka’s in Gardone. Won’t you sit down? Cigar? Cigarette?”

“Thank you, sir.” Bora stood and declined to smoke.

“Your temporary office is in town, at the Republican National Guard’s headquarters. By day’s end, a staff car and driver will be assigned to you. I made a nine o’clock appointment for 25you to pay a courtesy call to Marshal Graziani’s aide, Denzo di Galliano, and schedule a meeting with the marshal. Graziani’s role is little more than a sinecure, but his exalted rank keeps him happy. On your way out, see my chief of staff, Major Lipsky. He’ll show you around as needed and drive you to the Ministry of the Armed Forces.” A log in the fireplace hissed and flared up, like a tongue lashing in that burning mouth. “Be back for lunch at twelve sharp, so we can become acquainted. Before then, telephone our deep regrets to Cavalier Pozzi, owner of the stolen painting and textile merchant.” No details of the theft followed beyond what Hager had said, but, despite Sohl’s superficial calm, a grey pallor came over his face. Bora wondered just how precious the lost painting might be.

Across the hallway from the general’s office, from a small room lined in blond wood the chief of staff stepped forward. “Klaus-Etzel Lipsky, Herr Oberst. Welcome to Salò.” At once, he came close to undoing Bora’s reserve, by adding, “It was my privilege to serve with your late stepbrother in Russia. Commander Sickingen was as fine a flyer as I can envision.”

Bora’s mourning fortified him against blandishment. “In which capacity did you serve with Peter?”

“I was the squadron’s administrative officer. After my flight mishap, that is. A broken back does not interfere with paper pushing. I’m a lawyer by training.” Lipsky’s deeply set clear eyes discreetly ran over the badges and ribbons on Bora’s tunic – a predictable, quick reckoning of his worth. Bora took mental notes of his own. Wide-necked and fair, the major had the tanned looks of a skier or a mountain-climber. From his left ear to the neck, an ugly scar created the strange impression of a welding in the flesh. Campaign ribbons and badges told the rest. “Colonel, my office is at your disposal if you wish to review your orders.”

26Bora thanked him. Ten minutes later, he rejoined Lipsky and left the building with him. Outside, in the short walk to the gate, the sun eyed open through the clouds, and what had been a single glowing line across the lake spread into a generous sprinkle of brightness.

Lipsky drove a ridiculously small yellow convertible with a civilian licence plate. Only with the top folded back could two tall men hope to fit inside it.

“Is this the sort of car one finds in the German motor pool?”

“No, no. I chose it because I like it.” Lipsky reversed the car and headed south. “So, since you come as a liaison to Marshal Graziani, off we go to his Ministry of the Armed Forces in Soiano. You’ll see soon enough whether his Republican Army is a true embodiment of what he calls the Italians: the flower of all races, fragrance of the earth.”

Bora glanced over. “You cannot be serious.”

“He said so in public, less than three months ago.” Lipsky smirked, changing gears and flooring the gas pedal with a pilot’s gusto. “Doesn’t the marshal know we are the sweet-smelling bud of the universe?”

Bora did not comment. For a minute or so, he stared at the glossy clearness of the lake. Then: “What about Denzo di Galliano?” he asked.

“You’ll see.”

“That’s not an answer, Major.”

“Well, he’s an eminent prick.”

Such cheek was unheard of. Bora was astonished. How much did Lipsky know about him, that he allowed himself such familiarity? It suddenly came to him that he might be the officer who delivered Peter’s belongings to his parents after the crash. Hadn’t his stepfather described him as a “former pilot with a Polish-sounding name”? At the time, from his post in Russia, Bora had felt deprived of the right of being there 27himself, and not a little jealous. He chose not to ask Lipsky about it, and the major did not volunteer the information.

Looking at the map on his knees, Bora noted how virtually every small town on the lake-shore housed one or more ministries. Gargnano, in its scented strip of lemon and lime gardens, was where Mussolini lived. Maderno housed the Secretariat of the Fascist Party and Kappler’s Security Service. Foreign officials resided in a hotel at Fasano, not far from the German Embassy. SS General Wolff lived in Gardone, and so on. Southward, where they were going, a number of villas clustered here and there among palm trees and bougainvilleas. Entrepreneurs and militiamen sat side by side with Party devotees and those who only hoped to get out of there alive. Bora wondered how long it’d been since his last visit to La Schiavona, the family place at the northern tip of the lake. Six years at least. A handful of kilometres away from Mussolini’s headquarters, his grandparents’ summer home now lay beyond the freshly drawn frontier, in newly acquired German territory.

When the car turned right to reach Villa Omodeo, they had to show their papers to the marshal’s numerous guards. Waiting for permission to enter, Lipsky pointed to open swatches of land beyond the manicured garden. “Training grounds, and even a landing strip, Colonel. Rather grand. Closely watched day and night, because the marshal fears an attack against his person. I believe those you’ll actually deal with are Renato Ricci’s Republican National Guard, reined back into the regular army as of last August.”

“So I heard.”

“But even after Ricci’s sacking, the Guard does as it pleases: namely, it takes personal initiatives against the partisans, acts as a police and security force, and keeps the order … or the disorder. We control it, or think we do. Which is probably why you’re here.”

28Once through the gate, Lipsky left Bora at the villa’s entrance. No sooner did Bora walk in than an Italian adjutant came to greet him in the foyer. He was natty, polite and smelled of sweet cologne, but the upshot was that Colonel Denzo di Galliano was not in. In fact, he would not return until the following morning. All meetings were postponed. Marshal Graziani, on the other hand, had changed his schedule for the day; presently at his General Staff HQ at Bergamo, he would not be available for an encounter until Wednesday at the earliest.

Bora penned a terse note indicating that he’d called. “Wasn’t the colonel aware of my arrival?” he asked.

“Something urgent came up. I’m sure he’ll see you around ten-thirty tomorrow.” The adjutant had the noncommittal attitude of a bureaucrat, keeping information to a minimum. “It is Sunday, you know.”

Lipsky didn’t bat an eyelid when Bora came out moments later with a frown on his face. Nothing was said while they drove back to Salò. Even while waiting for an ambulance to exit an alley off Garibaldi Street, in a crowd of police uniforms and civilians, they looked on without speaking. Furtively, Bora swallowed two aspirins. Soon after, they came to a glum building with bars on the windows. “Your office is in there,” Lipsky informed him. “If you have any further questions …”

Bora was still irritated with the reception at Soiano. Generally, he would not discuss his orders with others; however, Sohl’s chief of staff must have been in the know, and his was a second, indirect offer of support. Trust came hard these days, so Bora replied with the first query that came to his mind. “What can you tell me about the overnight theft at the residence, and the painting?”

“The painting?” Lipsky stared at him. “It’s not just a painting. Why, it’s a work by Titian, Herr Oberst. Certified and worth a fortune. A spectacular Venus reclining on a couch, discovered 29by Conforti, the Jew. Our deep regrets won’t be quite enough for the owner. Which is probably why General Sohl is sending you to deal with Signor Pozzi. The general feels your presence here might be useful in that regard.”

“Really. How so?”

“He heard of your sleuthing abilities from an air-force acquaintance of yours, Colonel Habermehl.”

The talkative sop. God knows what else about me he’s let slip. Bora showed no overt annoyance. After all, Sohl never mentioned that he wanted the theft looked into. He decided it was his turn to try Lipsky’s reliability. “Who is Mengs? Do you know?”

This time Lipsky reacted with a quick wink. “I have no significant information about him, and I doubt anyone does. His office is at Maderno.”

“I see.” Bora meant to get his own fact-finding system going soon, since colleagues and trustworthy non-coms he knew were presently assigned to posts in the neighbouring cities. “Major, that cannot be all a general’s chief of staff is informed of.”

“But it is. I can’t imagine why he drove you in.” Lipsky’s arm stretched out in an impeccable Party greeting. “Would it be convenient if I had my things moved to my new quarters later today?” It was the only discreet signal to Bora that he was the very officer rudely dislodged the night before.

The Republican National Guard was aware of Bora’s coming. He’d been assigned an office, and he recognized the spur-of-the-moment busyness that often welcomed German officers. Halfway up the stairs, he was surprised, but only so much, to recognize the bantam-sized Captain De Rosa hastening down to meet him. Party salute on one side, army greeting on the other, and soon they were swapping comments about the facilities and the war.

30De Rosa acted with a mix of dignity and deference, as if they hadn’t quarrelled in Verona a year earlier. The dim state of current affairs and political events had seemingly cut his arrogance down to size. Sombrely pugnacious, his bold moustache grown bushier and shaggier, he spoke vacantly of units and numbers. He lavished on Bora maps, files and typed accounts of military operations, betraying disappointment at being assigned to the RNG from his post in the militia – the notorious Muti Legion. He showed Bora around, bluntly opened doors and slammed them shut; his mouth twisted when mentioning the hated name of this or that politician. It could be an active soldier’s intolerance for cramped headquarters, or not. At the end of the tour of the ground floor, De Rosa turned to Bora with a scowl. “My space,” he said, not “my office”, as he unlocked a pantry-like narrow room at the end of which sat an oversized desk. A far cry from his fine digs in Verona. On the wall behind the desk, a gory and tattered shirt stretched spread eagle. “Belonged to a comrade,” he explained grimly. “Killed on the eighth of August.”

Bora looked from the threshold. “And that thing on your desk?”

“It’s a skull.”

“I can see that.”

“Russian front, another comrade.” De Rosa half-closed his dark eyes. “We live in the midst of death, Colonel.”

“That is a fact. But, I must say, you were less morbid in Verona.”

“Morbid? Far from it. I celebrate by collecting photographs of our fallen brothers. Death, blood. Ours, and the traitors’. You must have seen the film of the execution at Verona.” (Bora had done, at the German command in Rome.) “Did you notice the coup de grâce fired into Ciano’s head?”

“Yes, both of them.”

31“Three.” De Rosa missed the irony. “It took me three. Death is our daily business, and Mussolini’s traitorous son-in-law deserved it. Do you by chance recall Marla Bruni, Colonel von Bora?”

“The soprano you were dating in Verona, yes.”

“I wish I’d never given her a motor car. She’s joined me here.”

“Well, bully for you. Does her husband know?”

“Of course not. He’s in Switzerland.”

Bora followed De Rosa upstairs, thinking of people and circumstances coming together. The circle closed. Being here was like seeking the trap and wilfully stepping into it – something he’d been mindful not to do for the past few years. Pressuring Lipsky before taking leave of him, minutes earlier he’d got out of him a quick piece of advice about Mengs, the Gestapo man. “Ask SS Colonel Dollmann.” It meant that Eugen Dollmann was here, too. The perilous intrigues of German-occupied Rome followed that ambiguous officer, who’d once called himself “dissatisfied with keeping his feet in less than three stirrups”. Standartenführer Dollmann’s acquaintance with Mengs pointed to a connection between the latter and Himmler’s office, or worse. Without seeing it, Bora smelled a trap, because the night before he had kept company with the hunters. At any rate, this morning he carried his diary safely in his briefcase. The circle left out its dead and wounded: Bora’s old chief, Admiral Canaris, arrested in July after the failed attempt on Hitler’s life and the dismantling of the Army Intelligence Service; colleagues and friends tortured and executed. Ranting trials before the People’s Court. And now he was being assigned to oversee anti-partisan operations in order to “curb Italian excesses”. This made least sense of all.

And what about Mengs? He knew nothing about him, although in June his friend Ralph von Uckermann – himself 32eventually bound for the gallows – had mentioned a Gestapo man at Salò, a certain Heinrich Müller, who had once been a henchman of the bloodthirsty late Reich Protector, Reinhard Heydrich. Why would SS plenipotentiary Wolff want to “curb excesses” in a fratricidal war?

Suddenly, the words “lovemaking” and “ludicrous” reached his ears from De Rosa’s chatter. Bora was startled. He acknowledged them with a “Sì, sì,” in Italian, as if he cared.

“I knew you’d understand, being a worldly man. Just think, Colonel von Bora, La Bruni is staying in the same pensione where my wife resides. My life has become an inferno.”

We all end up in the hell we fashion, there’s no doubt about that. “Well, should I feel sorry for you?” Bora showed more amusement than he actually felt. “Some men would kill to have your embarrassment of riches.”

“You think it humorous, do you? I’d kill to be free of them both.” Grudgingly, De Rosa resumed his role as a guide. Walking to Bora’s new office, he quipped, “But naturally you are faithful to your wife, as you said in Verona.” He looked meaningfully at the German’s right hand, from which the wedding band had vanished.

Bora entered the office, strode over to the window and threw it open. “Tell your men that I expect a working telephone by tonight and a set of unmarked, fresh maps of the area and surrounding mountainside. Please have the filing cabinet moved behind the desk, the rug taken out, the windows washed, and do not bother with a motor car. I’ll get my own from the German pool.”

De Rosa nodded. “I get it,” he spelled out in his perceptible southern drawl. “You’re here for him.” Because Bora said nothing, “Cristomorto, right?” he added. “They sent you here to try and catch him: but he’s one to steer clear of. He’s deranged.”

33There would be time yet to discover who this “dead Christ” was. Bora answered that he had no details. Yet that name, or nickname, and the way De Rosa, who was no coward, warned him to watch out, struck him unpleasantly, just as the monstrous fireplace in Sohl’s room had done. A partisan commander, probably: not the sort of adversary he was interested in facing after real war on the Gothic Line. Leaning out of the window, Bora studied the houses across the street, the clock tower to the left, and the cloudy, moist sky above. “Have a set of office keys made for me. I like to come to work early, and I stay late.”

Eleven-thirty, an idea of the organizational mayhem he was to mediate, and a need to breathe the outside air. Bora chose to walk to Sohl’s residence. On the way, he noticed that uniformed men and civilians were still milling about in the alley off Garibaldi Street, although the ambulance was gone. The sleepy-eyed police official he’d glimpsed at three in the morning, looking rather awake now, was exiting a doorway, shaking his head. From the open window above him came a sound, singularly high-pitched, like a dog’s frantic yelp or a woman’s wail.

“What happened?” Bora asked the policeman closest to him.

The man saluted. “A woman killed herself on the upper floor. The one making all this noise is a neighbour: she saw the body and we can’t get her to shut up.”

“Ach, so. And how did she commit suicide?”

“She hanged herself.”

The words came from the police official. “Cesare Vismara, Republican Police. May I help you?”

“No, I’m just curious.” Bora looked up at the shop sign above the doorway: Antiquities and Photographic Studio, Moses Conforti. “A spectacular Venus reclining on a couch,” Lipsky had said, “discovered by Conforti, the Jew.” Bora took a mental note and resumed his walk.34

Once it became clear that Sohl would not discuss Bora’s duties before his conference with Graziani, the conversation at lunch turned to the stolen painting. “Don’t you see that’s why they placed Lipsky at my side, when I had my own chief of staff until a month ago?” Unexpectedly, over grilled trout, Lieutenant General Sohl took advantage of Lipsky’s absence to gossip about him. “Göring himself sent him – this I know for a fact – and had the Venus not disappeared, he’d have made his move to secure it next week at the latest. I looked into Lipsky’s background, Colonel. Art. Art. His father worked for the Keller und Reiner art gallery in Berlin before starting an auction house on the Potsdamer Strasse. Imagine that!”

Disparaging colleagues was not something Bora cared for. He listened because there might have been more to this than chatter. “What then makes you think the Reich Marshal is not behind the disappearance?”

“You should have seen Lipsky last night, after the incident. He was beside himself. When you arrived, he’d just finished grubbing through the backyard like a boar, looking for tracks. No. I’m positive he spent the rest of the night on the telephone with Berlin.”

“He seemed rather composed this morning.”

“Pilots have poker faces. Don’t trust him.”

Before lunch, Sohl had insisted that Bora examine the frame of the painting. The canvas had been cut from it with a sharp blade, carelessly enough to gash the gold leaf in two places. “Done in a hurry, wouldn’t you agree?” The general had spoken the obvious with his lips around an unlit cigar.

Now Bora watched the ever-present cheroot sit like a grub by the general’s plate. The heat from the fireplace breathed through the open door of the studio, so much so that he could feel it uncomfortably on his neck. “What happened 35exactly?” he asked. “And how long was the upstairs left unguarded?”

“Maybe thirty-five, forty minutes. Less than an hour, anyway. There are half a dozen police units in town, ours and Italian, and still someone manages to toss a grenade into my backyard! Nothing but a loud bang, although two rear windows did explode, and a fire started in the trellises. I was asleep – it was past one o’clock – and I must admit the incident did cause a great deal of confusion. When I opened the window, a heap of dry leaves had caught fire and the smoke was suffocating. For a time, my men ran in and out with buckets of water. Then a fire truck came, followed by the police, the RNG and the SS. Thank God it started to rain. We assumed it was a partisan attack, but the thieves must have slipped in somehow, knowing exactly what to go for. Lipsky ran in from his hotel, and it was he who discovered the theft.” Sohl stared behind Bora’s shoulders, as if someone were watching the conversation. His cordiality sounded insincere. “You must realize this is more than mortifying for me. Signor Pozzi wanted to remove the painting before I moved in, but I told him it’d be perfectly safe with us.”

“How did he learn of his loss?”

“He owns another villa up the road, so it wasn’t long before he realized where the grenade struck. I had to telephone him about the theft.” A white-gloved private removed the empty plates, placed fruit on the table and left. “I told you Pozzi is a textile manufacturer. He owns five of the houses our forces occupy between Salò and Gardone. Little formal education but plenty of good investments. For him, the Venus was a pretty picture that cost him a bundle and was worth even more. Did you speak to him?”

“Briefly, as you ordered. He wants to discuss matters in person, so he’s invited me to dinner tomorrow night.”

36“Capital. You’ll see for yourself what sort of fellow he is.”

“He could be the sort who takes back what’s his,” Bora observed coolly. “Herr Generalleutnant, how many people have access to this residence?”

“No civilians. But there’s no telling how many art collectors have seen the painting ever since the Jew authenticated the Venus a year ago.”

“Conforti?”

“Yes, Conforti. Don’t let his Italian-sounding name fool you: he’s a Prague Jew. The SS brought him in at my request: I wanted to make sure he’d been sleeping in his bed and meant to see his reactions.” Sohl began to peel an apple rather clumsily. “If you’re wondering why we let a Jew stay footloose, it’s because the German authorities have ordered him to compile an inventory for us.”

“Is he married?”

“Not that I should know or care. Why do you ask?”

“A woman killed herself in the building where he works.”

Sohl stared at him with his nose in his wine glass. It was possible he was still mulling over reports of Bora’s investigative activities in Verona and elsewhere, no doubt exaggerated by Habermehl’s bibulous chatter. Unless his days in intelligence drew an all-knowing aura about him, that was far from the truth. Anyhow, the lieutenant general did not openly ask his advice. When Bora asked about the police official, he replied, “Vismara? Keeps to his side of the fence and seems capable.”

“How does he intend to investigate?”

Sohl folded his napkin and, holding it with both hands, wiped his mouth from side to side. “I haven’t put him in charge of the matter. It’s my opinion that Italians are behind the crime, although I don’t know whether the grenade attack was part of the scheme or an extraordinary coincidence, clearing the way for someone waiting for an opportunity to enter the 37premises. Speaking of which, dinner at Pozzi’s is a good sign. You’ll see what luxury some Italians still live in, Colonel. You are, of course, authorized to hear what he asks in consideration of his loss.”

Bora glimpsed a small, second trap in the grass, only inches away from the large one. “So, who is to look into the Venus’s disappearance, sir?”

“Why, you are. Until Graziani shows up on Wednesday, there’ll be time for you to make some sense out of this embarrassing question. Vismara will be at your disposal, and the Jew will tell you all about the painting. My men here were remiss; I’m kicking a couple of them out to the front line, but feel free to question them first if you want to. As for Lipsky, he’s off on my orders to Milan. With the roads as they are, and the car he drives, it’ll take him hours just to get there. To begin with, I suggest you examine the backyard. Then, after you settle down, go and see the Jew for details of the painting. Tomorrow night, bring our regrets but no contrition. I envy you, Colonel, because you’ll eat grandly at the cloth-maker’s. He has a handsome daughter, too, which doesn’t hurt.”

“In my experience, small towns are quick to elect their beauty queens.”

“You’ll be the judge.” Sohl picked up and lit his cheroot. “They say she shaves all over … not just her armpits, you understand.”

Bora only half-succeeded in hiding his surprise. “It’s unconscionable that such gossip should circulate about a lady.”

“Oh, her late husband was a sailor. He once talked in his cups. And in a small town, once is all it takes for such titbits to propagate.”

Until five o’clock Bora stayed in his new office, familiarizing himself with the material De Rosa had given him as well as 38German intelligence reports on the military situation east and west of the lake. He also read expected but discouraging news about Fascist bickering and infighting, of Denzo’s antipathy towards the RNG and vice versa, of Marshal Graziani’s outbursts and Mussolini’s grumpy silence with most everyone. As soon as the telephone was hooked up, all lines being run and controlled by the Germans, he reserved a call to his old divisional headquarters, to ask about the regiment’s advance on Brescia. The operator told him that connecting a long-distance call could take hours. “No less than four, Colonel.”

Disappointed, Bora stood up to stretch. His left leg and shoulder ached. The chair was singularly uncomfortable, and the writing implements in the desk drawer sparse and poor. The ugly calendar on the wall, as well as the map hanging askew next to it, suddenly nettled him. He removed the calendar and tossed it into the bin.

It seemed to him that he was preparing for something expected, something for which order and neatness were antidotes. He had to monitor a certain obsessive dislike for shabbiness, for lack of precision and punctuality. Thus, Bora watched himself as if from without at this odd point of his life, neither liking nor rejecting what he saw: a young man determined to keep control even over his tendency to keep control.

Sometime during the summer, he had stopped dreaming about his wife Dikta. Other dreams – often nightmares, or sometimes plain images of riding along Polish or Russian roads – had persisted. Remedios came and went from recollection, along with memories of Spain, where he’d first made love to her. Of Nora Murphy, he had not dreamed in weeks: this, too, might mean something.

It called, for lack of better things, for a cup of coffee. When he left the building, he saw Vismara across the shadowy street apparently waiting for him.

39“Colonel, I understand you’re to look into the theft, so I’ve brought you the notes I took on the crime scene.” He pulled out of his pocket a folded, typewritten sheet, so awkwardly that it wafted to the ground before reaching Bora’s hand. Vismara stooped to retrieve it. “Sorry. Here.”

Without glancing at it, Bora placed it inside the cuff of his left sleeve. “I’ll let you know.”

Had the policeman refrained from entering RNG headquarters because of some power struggle or other? “I typed my phone number on the sheet, Colonel.”

“I prefer to communicate in person, if I can. Where is your office?”

“In the questura building on the square.”

“I’ll come tomorrow, as I can.”

At eight-thirty in the evening, Bora was finally able to connect with the 362nd ID headquarters. When he left work for good, he found a Luftwaffe private at the door below, with a dated but well-kept Fiat 1100 and a card from Lipsky that read: I know you said you wanted to pick your own, but this is the best of the lot, and, if you don’t take it now, it’ll go to Denzo’s adjutant.

By the time he retired, Bora had secured a pack of looted Chesterfields for old times’ sake, swearing not to smoke them. Some of his clothes needed ironing after Mengs’ minion stuffed them inside the footlocker. He hung the rest neatly. As for his boots, they sat properly shined outside his door.

He lay down dressed as he was, determined not to think or close his eyes. But when the power failed for the nth time that day, he was, whether he liked it or not, consigned to the dark. Flat on his back, he felt blood pounding in his veins, as if the heart muscle were straining, so he sat up in bed. Names and numbers of enemy units and partisan bands flashed before him; his night ride came back to mind in every unnerving detail. In 40order to fight anxiety, he found himself thinking of the Venus: how to find her, and whether Sohl really expected him to do so. Unknown, unseen, she somehow applied a gentle balm to everything else and provided the safest concern for the night.

A few kilometres to the north, in his deathly quiet Maderno office, Jacob Mengs leafed through pages by candlelight. The files before him were colour-coded, each colour conjuring a response in his mind. Entries dated back seven years, consecrated by bold signatures in black and blue ink; photographs, letters, addresses, names … Mengs read every page as a piece of the puzzle, to be secured and glued to the rest. One shouldn’t break rules, he reasoned. But how I admire those who break them well. When at last the power flickered back on, he twisted the gooseneck lamp to light up his desk like a beacon and began to write in intricate German script, where C’s looked like Z’s and H’s like F’s.

2

SALÒ, MONDAY, 16 OCTOBER 1944

Captain Parisi, Denzo’s adjutant, called shortly after eight, to relate that il signor colonnello was regrettably detained in his present location and would not be able to meet his German counterpart until the afternoon. Bora, who had been reading reports on the fierce fighting against partisan bands in the Ossola Valley, had just got three guardsmen to haul in a decent desk chair, a radio and a bookshelf. He ordered them to leave so that he could berate the adjutant at his ease but did not succeed in extorting news on Denzo’s whereabouts.

Disgruntled, he went back to his papers. The Ossola operation might succeed, yet the existence of an independent “partisan republic” spoke volumes about the situation in the western mountains. By comparison, monthly intelligence from Brescia army headquarters was less sanguine. It signalled activity of the irregulars from mid-August to mid-September along the Oglio River and Lake Iseo, fifteen acts of sabotage against thirty-two recorded in July and August, and twenty-two during the previous period. The air raids, disastrous in the summer, had diminished, too. Intriguing data, difficult to evaluate at this point: of immediate relevance to his charge was the news that seven Germans had fallen prisoner to the bands – three of them officers – vis-à-vis thirty-seven rebels dead and forty-two taken in. If needed, the margin for negotiation, one to six, was reasonable enough.

What surprised him was having received SS field reports as well; it was hardly their style. What was Plenipotentiary Wolff up 42to? De Rosa added scraps of information by the hour, garnered from a handful of disparate Italian units. Jotted down in the glow of ideological passion, Bora learned more, and less, about Cristomorto than he wanted to know. Reliable data about the size of his unit and area of action were missing. His nom de guerre – Xavier – had emerged in relation to a July shoot-out in Val Sabbia, where two Germans had fallen. He was credited with acts of “beastly violence” against not only the enemy, but civilians as well. To Bora, some of these seemed to be embellished by hearsay and scarcely believable; others – mutilation of the adversaries – he’d last heard of on the Eastern Front, where he’d gathered such gruesome information for the German Army War Crimes Bureau. He scribbled: Find out if Cristomorto served in Russia, and, Unusual that we should know his real name. But is it his real name?

By nine o’clock, the weather had taken a turn for the better. Bora set up an appointment with Vismara and ordered flowers to be sent to the Pozzis’ residence in anticipation of his dinner date. Because the Fiat still had a civilian licence plate, he planned to drive it before lunch to Wehrmacht headquarters, list it as a German army vehicle and carry out a brief reconnaissance of the lakeside to its political northern terminus, Gargnano.

As he left his office, De Rosa approached him. Bora, who was using his teeth to pull up and adjust his right glove, expected to receive one more typewritten sheet, but De Rosa just stood there. “Have you heard the Radiosender news? Field Marshal Rommel died of his wounds on Saturday.”

“This is called shivviti, is it not?”

In flawless Italian, it was the first thing Bora told Conforti, nodding to a small plaque by the door. He added nothing for half a minute or more, looking around discreetly. His 43