0,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Quickie Classics

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

Set in seventeenth-century Puritan Boston, The Scarlet Letter traces Hester Prynne's public shaming for adultery and the hidden complicities binding Dimmesdale, Chillingworth, and the uncanny child Pearl. Hawthorne fashions a dark romance whose ceremonious prose and intrusive narrator weave allegory and psychological realism. Emblems—the crimson A, scaffold, and forest—structure scenes of light and shadow, while the novel, a hallmark of the American Renaissance, interrogates conscience, authority, and the spectacle of punishment. A descendant of a Salem witch-trials magistrate, Hawthorne long brooded on inherited guilt and New England's theology; those obsessions suffuse his art. His dismissal from the Salem Custom House and the archival habits it fostered shape the book's prefatory frame and its fascination with documents and memory. Years of tale-writing refined his symbolic method, enabling a critique of communal judgment that is historically situated yet inwardly modern. This work rewards readers who prize dense symbolism, ethical complexity, and an exacting historical imagination. Assign it in courses on American literature, religion, or law; or read it privately for its inexhaustible study of shame, secrecy, and forgiveness. Few works so lucidly reveal how personal desire and public authority collide, making The Scarlet Letter indispensable to any library of serious fiction. Quickie Classics summarizes timeless works with precision, preserving the author's voice and keeping the prose clear, fast, and readable—distilled, never diluted. Enriched Edition extras: Introduction · Synopsis · Historical Context · Author Biography · Brief Analysis · 4 Reflection Q&As · Editorial Footnotes.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2026

Ähnliche

The Scarlet Letter (Summarized Edition)

Table of Contents

Introduction

In The Scarlet Letter, Nathaniel Hawthorne builds a relentless drama of public judgment colliding with private conscience, where a community’s rigid codes press against human fallibility, a visible mark seeks to define a woman’s life while inward truths resist containment, shame threatens to eclipse compassion, surveillance breeds secrecy, and the struggle to live honestly within unforgiving structures turns sin into a mirror that reflects society’s own fears, hopes, and hypocrisies, asking whether punishment can purify, whether love can survive scrutiny, and whether identity can be reclaimed when a single symbol attempts to capture a soul’s complexity.

First published in 1850 in the United States, The Scarlet Letter is a historical novel set in seventeenth-century Puritan Massachusetts, primarily in the Boston area and its surrounding wilderness. Hawthorne frames a bygone era with a reflective narrator who examines inherited moral legacies and communal order. The book blends psychological insight with symbolic design, engaging the conventions of romance while remaining grounded in social realities. Its austere streets, meetinghouse, scaffold, and forest create a vivid moral landscape shaped by law, scripture, and custom. Within this faithfully evoked milieu, Hawthorne tests the boundaries between civic authority and the irrepressible motions of the heart.

The novel opens with a woman emerging from prison carrying an infant and compelled to wear a scarlet emblem that announces her transgression to all who see her. She refuses to reveal the child’s father, and the town’s response creates the crucible in which the story unfolds. Hawthorne writes in measured, richly figurative prose, guided by an observant, morally inquisitive narrative voice that circles events, interprets symbols, and invites reflection. The tone is grave yet humane, attentive to suffering and endurance. Readers encounter long, sinuous sentences, scenes of ritual and rumor, and a steady interplay between external spectacle and inward conflict.

At the center is Hester Prynne, working, mothering, and thinking under constant scrutiny, her artistry and self-command complicating the crowd’s desire for simple judgment. Her child, Pearl, moves through the world with a wild clarity that unsettles the tidy categories adults prefer. A revered minister, vulnerable to the demands of sainthood, and a learned man, intent on reading hidden signs, become entwined with Hester’s fate, each embodying different responses to secrecy and guilt. Around them, magistrates, gossips, and neighbors register every fluctuation of rumor. The natural world—the forest and its edges—offers counterspaces where official meanings can falter and unexpected meanings appear.

Hawthorne’s themes remain sharply etched: the power of a label to constrict or reshape a life; the tension between confession and silence; the limits of punitive justice; and the fragile possibility of mercy. He explores how communities construct morality and how individuals negotiate that construction, sometimes internalizing it, sometimes resisting it. Symbols recur with insistent variation—the embroidered letter, the scaffold’s public stage, the shifting play of light and shadow—inviting readers to test interpretations against experience. The novel probes the difference between law and conscience, and considers whether virtue can be coerced, performed, or only earned through sustained attention to truth.

For contemporary readers, the book’s inquiries resonate wherever reputations are made and unmade in public view, where institutions claim moral authority, and where gendered expectations shape judgment. Its portrayal of stigma, resilience, and ambiguous repentance speaks to debates about accountability and the possibility of repair. The novel questions the uses of exposure and secrecy, asking what communities owe the vulnerable and how authority justifies itself. It also examines how art, craft, and labor can become forms of ethical self-definition. By tracing the pressures that attempt to fix identity, Hawthorne offers a humane argument for complexity, patience, and imaginative sympathy.

Approaching The Scarlet Letter with attentiveness to voice and setting enhances the experience: the narrator’s meditative distance, the cadence of the sentences, and the recurring spaces together guide interpretation. Readers need not resolve every symbol to feel the book’s force; instead, following how meanings change from scene to scene reveals the work’s subtle architecture. Hawthorne balances restraint with intensity, allowing emotion to gather gradually rather than erupt. The result is a novel both accessible and layered, one that rewards re-reading and invites ethical conversation. It asks for patience, empathy, and a readiness to consider how judgment works—and on whom it falls.

Synopsis

Nathaniel Hawthorne’s The Scarlet Letter (1850) opens with a reflective narrator stationed at the Salem Custom-House who discovers a tattered letter “A” and a manuscript recounting a seventeenth-century Puritan scandal. This frame situates the tale in colonial Boston, where communal authority, religious orthodoxy, and public rituals define social life. The narrator’s curiosity gives way to a historical reconstruction of Hester Prynne’s ordeal, establishing a measured, observational tone that blends moral inquiry with psychological portraiture. From the outset, Hawthorne signals his concerns: the weight of law versus conscience, the shaping power of memory and record, and the ambiguities surrounding sin, punishment, and interpretation.

The narrative proper begins with Hester emerging from prison, cradling her infant and wearing an elaborately stitched scarlet letter on her chest. The town gathers for a scaffold scene that publicly marks transgression and demands confession. Hester refuses to reveal her child’s father, a choice that scars her reputation and hardens communal judgment. Among the onlookers is a recently arrived scholar with a troubled past, who recognizes Hester and resolves to study the hidden causes behind visible shame. The spectacle introduces the book’s ritual pattern—public exposure, private resistance—and anchors the conflict between a punitive society and a defiant individual.

Following her release, Hester settles at the edge of town, supporting herself through needlework prized for its skill yet tainted by stigma. Her daily life is a mixture of service and isolation; she aids the needy, even as many spurn her. The scarlet letter’s emblematic meaning evolves with the townspeople’s shifting perceptions, reflecting how signs acquire new interpretations over time. Hester’s daughter, Pearl, grows into a vivid, questioning presence whose temperament seems to mirror the community’s unease and her mother’s inner tensions. Their close bond, crafted under scrutiny, becomes a testing ground for themes of inheritance, identity, and moral education.

Concern rises among magistrates over Pearl’s upbringing, prompting a formal review of whether the child should remain with Hester. Within a stately household, authorities scrutinize Hester while a revered minister pleads for compassion, shaping the outcome. The episode reveals the town’s hierarchical power and the subtle sway of eloquence. It also underscores the contrast between external order and internal conflict: as officials assert doctrinal certainty, signs of spiritual strain surface in those most trusted to uphold it. The scene expands the social field—governors, clergy, gossips, and outsiders—against which Hester navigates her rights and responsibilities as a mother.

Meanwhile, the newly arrived man of learning insinuates himself into the community as a physician, becoming intimately involved with the ailing minister whose pallor and agitation suggest a burdensome secret. Professionally attentive yet privately probing, the physician studies the minister under the guise of care, seeking knowledge that blends medicine with moral diagnosis. The relationship intensifies the novel’s psychological focus: the slow corrosion wrought by obsession, and the imprecision of reading bodies and signs. Hawthorne explores how scrutiny can both reveal and distort, and how the hunger for truth may shade into a more personal, driven quest for mastery.

Hester’s isolation sharpens her insight, and she confronts the physician about the destructive course he pursues. An earlier, concealed bond between them complicates obligations and blame, and a hush of secrecy continues to govern their interactions. Later, in the forest beyond Boston’s strict boundaries, Hester and the minister speak candidly about sin, responsibility, and the possibility of a life defined by conscience rather than fear. Nature, unconfined by the town’s rules, seems to momentarily sanction what society denies. Pearl’s lively presence in this setting emphasizes how innocence and curiosity can unsettle rigid moral frameworks without resolving them.

As civic and church calendars converge on an important holiday, public ceremonies draw townspeople and visitors into a festival atmosphere. Hester’s visibility increases amid the crowd’s fascination with her emblem, while the minister prepares to address the occasion with notable solemnity. Sailors, officials, and villagers create a tapestry of voices and expectations that heightens suspense around the intertwined fates of the central figures. The physician’s watchful vigilance tightens, and Pearl’s searching questions continue to press on the mystery at the story’s core. The scene gathers narrative momentum toward a moment of heightened publicity and decision.

Throughout, Hawthorne structures the tale around recurring scaffold episodes that punctuate private turmoil with public ritual. Symbols proliferate: the letter itself, Pearl’s mercurial energy, the rosebush by the prison, shifting light and shadow, and stray phenomena that invite moral reading. The narrator—alert to history’s distortions—filters events through a lens attuned to ambiguity, suggesting that meanings depend on the viewer as much as the sign. The novel’s language and imagery trace a spectrum from penitential gloom to tentative grace, showing how communities codify transgression while individuals grapple with conscience in the flickering interplay of shame, sympathy, and hope.

Without disclosing later turns, The Scarlet Letter endures for its evenhanded examination of law, mercy, secrecy, and self-fashioning. It presents a community intent on preserving order, yet vulnerable to the costs of rigid judgment, and individuals whose private reckonings exceed public categories. Hawthorne situates moral questions within a tangible past while granting them modern resonance, illuminating how symbols constrain and liberate, how guilt can deform and refine, and how compassion can reframe memory. The book’s lasting significance arises from its refusal to simplify: it invites readers to weigh justice with charity and to consider how meaning is made—and unmade—over time.

Historical Context

Set in mid-seventeenth-century Boston, The Scarlet Letter unfolds within the Massachusetts Bay Colony, established by English Puritans after 1630. The colony’s civic and religious life were tightly interwoven: only “freemen” admitted to church membership could vote, magistrates enforced moral statutes, and ministers exerted strong social influence though churches governed themselves by congregational polity. Public space embodied discipline, from the meetinghouse to the marketplace scaffold used for confessions and punishments. Town and General Court institutions defined daily order, while English common law adapted to local “liberties” structured criminal and family regulation. This framework supplies the novel’s civic stage and the community’s authority over private conduct.

Puritan New England organized its churches by the Cambridge Platform of 1648, affirming independent congregations, a regenerate membership, and discipline of visible saints. Civic identity rested on a covenant ideal: households pledged obedience to God’s law, while neighbors monitored conduct through church admonition and civil prosecution. Sabbath attendance, modest clothing, and restrained behavior were publicly expected. Literacy was encouraged so individuals could read Scripture; Massachusetts mandated town schools in the 1640s. The minister’s pulpit and the magistrate’s bench reinforced one another, producing a culture of communal scrutiny. This religious-legal matrix underlies the novel’s emphasis on reputation, confession, and interior conscience judged before a watchful public.

Colonial law codified moral offenses with unusual severity. Massachusetts adopted the Body of Liberties in 1641 and subsequent capital laws that, following biblical models, made adultery a death-eligible crime, though executions were rare. Courts frequently punished sexual and family regulation cases with fines, whipping, and public penance at the scaffold. Stocks and pillories dramatized judgment to deter others. While Massachusetts did not regularly require symbolic letters, the neighboring New Haven Colony’s 1656 code prescribed that convicted adulterers wear a capital “A” on their garments. Such statutes and rituals of shame provide the legal imagination for the novel’s scene of public exposure and enduring stigma.

The colony’s unity was repeatedly tested by religious dissent. The Antinomian Controversy of 1636–1638 centered on Anne Hutchinson’s emphasis on inward grace over moral law; she was tried by the General Court, banished, and later excommunicated. Massachusetts also punished Quakers who defied banishment orders; between 1659 and 1661 several were executed on Boston Common, including Mary Dyer in 1660. These proceedings were highly public, binding theology to civic order and defining the limits of tolerated belief. The community’s insistence on visible conformity and punitive spectacle forms a crucial backdrop for a narrative concerned with conscience, authority, and the costs of dissent in a tightly knit society.

Colonial household order rested on patriarchal norms shaped by English common law and Puritan statute. Under coverture, married women’s legal identities were subsumed under their husbands’, while magistrates supervised marriage formation, sexual conduct, and child support. Courts routinely prosecuted fornication and “bastardy,” imposing fines, whipping, or compelled acknowledgment of paternity to prevent the town from bearing support costs. Naming and reputation carried tangible consequences in church discipline and civil standing. Literacy, catechism, and catechetical instruction knit families into the moral economy, but breaches of sexual order drew swift, exemplary correction. These structures clarify the stakes of female transgression and communal judgment that the novel scrutinizes.

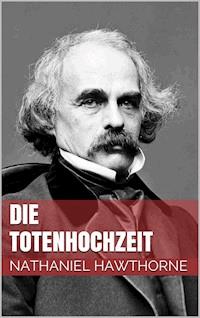

Nathaniel Hawthorne, born in Salem, Massachusetts, in 1804, wrote The Scarlet Letter soon after losing his post as Surveyor at the Salem Custom House in 1849. The book appeared in 1850, prefaced by “The Custom-House,” which reflects on local politics and the federal patronage system before introducing a purported colonial manuscript. Hawthorne was acutely aware of New England’s punitive past: his ancestor Judge John Hathorne served in the Salem witchcraft trials of 1692. That legacy of public accusation, legal theology, and inherited guilt shaped his interest in moral history. He mined colonial chronicles and court records to give the narrative a distinctive documentary atmosphere.

The novel belongs to the American Renaissance, a period around the 1840s–1850s that produced major works by Hawthorne, Melville, Emerson, Thoreau, and others. In New England, Transcendentalist debates about intuition and self-reliance circulated alongside expanding reform movements—abolitionism, temperance, and early women’s rights, signaled by the Seneca Falls Convention in 1848. Hawthorne lived in Concord in the 1840s, near leading Transcendentalists, and later formed a brief literary friendship with Herman Melville. Against this intellectual background, his return to Puritan Boston allowed a measured inquiry into authority, conscience, and gendered reputations without directly depicting contemporary controversies. The historical setting creates distance for examining persistent moral and social constraints.