8,63 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Seren

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

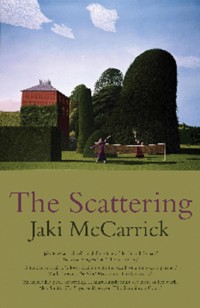

Borders haunt this debut fiction collection from prizewinning writer Jaki McCarrick: the Irish border where she lives, the boundaries of the natural world, and the darker edge of human nature, even the supernatural, here with an 'Ulster Gothic' twist. From small-town Louth and Monaghan to London, Florida and New Orleans, and back in time to the dawn of humanity, these stories explore the spaces between certainty and doubt, dependency and freedom. We witness the psychological fall-out from catastrophe and constraint, the pain of dual and fractured identities, the experience of emigration. Above all, what it means to be alive in a fraught and ever-changing world. Jaki McCarrick is a playwright, poet and short-story writer living in Dundalk. She studied at Trinity College, Dublin, and Middlesex University, gaining distinction and first-class honours. She has won many awards for her work and her plays have been performed (and read) in London, Belfast, Galway, Philadelphia and New York.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 361

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2013

Ähnliche

Contents

Title Page

Endorsements

Dedication

Dostoyevsky Quote

By the Black Field

The Badminton Court

1975

Hellebores

The Scattering

Painting, Smoking, Eating

The Congo

1976

The Burning Woman

The Sanctuary

Blood

The Visit

The Tribe

Trumpet City

The Stonemason’s Wife

Stitch-up

The Hemingway Papers

The Lagoon

The Jailbird

Notes

Acknowledgements

About the Author

The Scattering

a collection of short stories

by

Jaki McCarrick

The Scattering’

‘Jaki McCarrick tells a chilling tale of death and despair.’

The Irish Emigrant

‘The Sanctuary’

‘…a tender story ofmourning and longing.’

writewords.org.uk

‘Of particular note… Jacqueline McCarrick’s “The Sanctuary”; a tender portrait of a lover dealing with the death of a long-term partner.’

Mark Brown,The Short Review

‘The Badminton Court’

‘I was totally knocked for six by this story. It is an incredible piece of writing… The spare, sinewy sentences had me going over and over them; and such economy of writing! I must, simply must see more of her work…’

Alex SmithThe Frogmore Papers

‘The Visit’

‘“The Visit” takes the reader deep into old sadnesses and life-changing feuds which still burned under the surface of Irish society at the time of Bill Clinton’s visit.’

Susan Haigh,The New Short Review

‘By the Black Field’

‘My highlights to date would be: Jaki McCarrick’s “By the Black Field”... it has such an understated menace running through it and the writing is so subtly coloured, it reads like looking at a painting.”

Brian Kirk,Wordlegs

Leopoldville(play)

‘A superbly dark, taut thriller…. A fascinating piece of theatre.’

Deborah Klayman,RemoteGoat: 4 Stars

‘Impossible to shake off, the effects of this show plaster themselves on its audience… a stellar script… Expect to leave shaken.’

Naima Khan,Spoonfed Theatre Journal: 4 Stars

‘A sharp, well-observed piece of writing that is performed beautifully by this young, ensemble cast. The tension builds and builds throughout the play culminating in a harrowing twist that both excites and disgusts in equal measure… Fantastic work.’

Phil Tucker,Broadway Baby, 5 Stars

‘A fantastic, haunting, terrifying play… very strong, young cast & tight direction. It’s the winning entry for The Papatango New Writing Competition 2010 and rightly so…’

Shenagh Govan,The Group, Theatre Royal Stratford East

‘All the familiar ingredients are here: rustic eccentricity, colloquial lyricism, the Troubles. Yet fine performances and a subtle handling of the shades of morality lift this above the ordinary.’

Kieron QuirkeEvening Standard:4 Stars

‘A powerful play’

Nina Steiger, Soho Theatre

‘I love her voice’

Simon Reade, Bristol Old Vic

The Mushroom Pickers, Gene Frankel Theatre, New York

‘There’s a great deal to admire in new Irish playwright Jacqueline McCarrick’s debut work “The Mushroom Pickers”… a compellingly dark and difficult play… steeped in the dialect and lore of Co. Monaghan… one of the play’s major strengths is its strong sense of place – the local landscape is presented throughout as both beguiling and dangerous – and McCarrick knows how to sift drama from the tensions and realities of everyday border county life… McCarrick’s play is unique in that it presents a part of Ireland rarely seen on Irish stages, and the playwright presents the realities of that region with courage and rare honesty… (the company) is also to be thanked for bringing this challenging new production to the New York stage for the first time.’

Arts Editor, Cahir O’Doherty,New York Review

For my father,

and in memory of Pamela Von Hunnius

Each of us is responsible for

everything and to every

human being.

DOSTOYEVSKY

By the Black Field

Angel was building a fence right along where his land cut down to the river, not because the river might burst its banks, which it was prone to do in the rain-heavy months, but because he or Jess or the child might accidentally fall in, especially on a moonless night when they might not be able to see. He was concerned because the ground was too soft now for the poles, and he was convinced that what he should have done was rebuild his grandfather’s wall as far as Henry’s.

A pleat formed between his brows. He was bothered and his eyes hurt. He lacerated himself for his persistence – and for wasting good money on the poles.

He looked up at the swaying pines as if seeing his wife’s face: no doubt she would be disappointed in his efforts. He turned to the newly ploughed field. Soon it would be ready for sowing. He thought of summer when there would be knee-high potato stalks with their purplish and white-wheeled flowers filling its black space.

He heard a woman talking on the road. It was Margaret, the frenetic, spindly woman who lived round the turn on the other side of the ring fort. He could never say what, exactly, but something troubled him about her. She and her husband Jack ran a computer business from their blue dormer. She was nice enough to him and Jess when they first arrived, and when they’d meet her on the road she would say hello and sometimes ask them about themselves. But still, Angel disliked her; he saw in her a kind of desperate and cold ambition and it reminded him of London. Her mustard-coloured MG would regularly screech to a halt out in the road. She’d have forgotten something that the small, wiry Jack would invariably be asked to retrieve. Or she’d pull over to take or make a call, and talk so loud the birds would fly out of the trees. And there she was now, Angel thought, at it again. Though this time she seemed to be alone, and was walking.

He was heavy with depression: a feeling of length in his stomach as if a fist was inside him pushing down on his breath. He set about methodically collecting the poles then stacked them against the side of the house beside the turf.

There were times when Angel thought that the land communicated with him. He knew that this was irrational, and probably due to overwork, and to the fact that he had not yet lost his city-born infatuation with green fields (and also, possibly, because he’d spent his childhood summers in this place and had fond and lively memories of it). He imagined that after a few more years on the farm he’d be as hardnosed towards the land as every other farmer he knew. Still, he could not dispel the sense he had that wherever he went on his six acres he was not alone. He would feel guided towards sowing this or that crop, doing this or that farm job. Sometimes he would just put his ‘delusion’ down to the voices of men and women at work in nearby fields being carried on the breeze or downriver. That’s what he told himself. He said nothing about the experience to his wife.

As he closed the door behind him, Jess brushed past carrying his grandmother’s large blue-flowered plate (that she had left to him) filled with steaming vegetables. He quickly washed his hands and changed his clothes then tucked himself into the table.

‘The poles are all wrong, Jess,’ he said, his mouth full of food.

‘How come?’ Jess asked.

‘It’s too wet. I should have hired some help and built the wall.’

She was strong, like a thick white lily in the sunshine. And now, in the eighth month, more unavailable to him than ever. Since they moved here she seemed to fall into an ever-deepening daze, Angel thought. He knew she had no love for this land. Not everyone was able to engage with nature the way he could, he knew that. He had not expected her to love the place, just to appreciate something of its beauty and charm, as she had seemed to do at first. But lately she’d begun to talk about London and how she missed it, and the talk had annoyed him. He felt as if he had failed her. He looked at her across the table from him. She was beautiful with her long white hair, and eyes that were as pink as his own.

The house, lost on the end of the long road before the turn towards Carrick, was set into a wide, elder-protected circle, further shaded by pines and a large oak. A dead beech stump, host to clusters of oyster mushrooms, sat behind the front stone pier. It was one of the few restored cottages of its kind in the barony. All the other homesteads of a similar age in the area served as a source for walls, or were used as rickyards or byres – or were simply abandoned. While he had rehabilitated the old house, his neighbours – the Dalys, Cassidys, Conlons – had all set up in the soulless, heavily mortgaged piles they’d had built alongside stone cottages (in various stages of dereliction) in the same way the Church had established itself throughout the land on pagan sites and shrines. Before they had come, the house had known no modernity, though latterly, with electricity, his grandmother had had ‘the wireless’. And up until now it had been shelter (during the summers, anyway) to only one albino child (and how he got into the works nobody knew), and that was Angel.

In the autumn there had been a rat in the barn and it was this, Angel believed, that had triggered Jess’ mistrust of the place. At first they thought it was a mink; a neighbour who had come home from Australia had begun breeding Swedish mink for fur and all the mink had escaped. A rat, however, was another story. Angel had stalked the rat for three days. Then, one morning, he found it on the barn floor, sleeping, and took a hammer to it. His frenzied attack on the creature disturbed him, and he knew then that he, too, had begun to change in the place.

After the meal, he cleared the plates and sat by the fire. He watched his wife as she walked to the window and looked out. He wondered if, after the child was born, she would want to stay.

‘Will we go out and watch the weather, Jess?’ he asked, hoping she would stand with him on the porch and look up at the stars as they had done when they first came.

‘In a bit,’ she replied, and went to lie down in the back room. He pulled his chair into the warmth and thought of the fence. It was important to get a barrier erected. A partially sighted child could not be allowed to wander a farm left unguarded to a deep river. He’d call in some aid and build a wall. He’d call someone tomorrow. There was more than enough stone; round the sheds there was plenty, and it was all free.

He must have fallen asleep. There was a heavy rap on the door and when he awoke he had thought for a second he was back in the flat in Willesden and was confused. He went to the door and opened it.

‘Terence O’Hanlon?’ the tall garda asked. Angel could smell cigarette smoke off the man’s breath.

‘That’s me,’ Angel replied.

‘Can I come in?’ Angel hesitated. He’d heard stories about people calling to remote homesteads under all sorts of pretexts, then looked out and saw the squad car. He asked the garda in, shut the door behind him and dropped the latch. Jess came out of the room, slowly tying her hair. He watched the garda staring wide-eyed at Jess’ long white hair flashing around the low-lit room.

‘I’m sorry to have bothered you both,’ the garda said.

‘No. It’s fine. What’s the problem?’ Angel asked. The garda seemed nervous.

‘Terrible storm forecast,’ the garda said.

‘I heard.’

‘Messing it up terrible these days, aren’t they, the weather people?’

‘They are.’ Angel laughed, thinking of his poor day with the poles.

‘What can I do for you, Officer?’

‘Patrick is fine.’

‘Patrick. What can I do for you?’

‘Please. Sit down,’ Jess said, and gestured to the garda, who took Angel’s chair by the fire.

‘Look, I just have to ask you both not to go far, at least not out of the local area, if you don’t mind. For the next couple of days anyway.’

‘Why? What’s going on?’ Jess asked, alarmed. The garda seemed put out and wiped his mouth with his hand which, Angel observed, was as wide and thick as a brick.

‘I suppose you’ll know soon enough, but a body was found this evening up there in the bog. The other side of the ring fort.’

‘A body?’ said Jess.

‘Aye. A woman. A dead one,’ the garda replied.

‘Who is it?’ Angel asked.

‘Your neighbour, actually. Margaret Murphy. Lives, or lived, I should say, up in the blue house. These are hard times now and people do crazy things. We need to make enquiries all around. Who knows what goes through a person’s mind these days, huh? The figures are up.’

‘The figures?’ Jess enquired.

‘Suicide,’ the garda said. ‘We have a mink problem as you know in these parts. But it is my belief she must have been dead already for them to have done that to her.’ Angel sat Jess down into a chair.

‘Did you know herself and Jack Murphy?’

‘Only in passing,’ Angel replied.

‘Fresh over from England, Mr O’Hanlon, are you?’

‘Well, yes and no. We’ve been here since last spring.’

‘Keep yourselves to yourselves do you?’

‘Mostly, yes.’

‘I seemed to recall word of a fella with the look of yourself come to the old O’Hanlon place from London.’

‘That would be me then,’ Angel replied, curtly.

‘Right. Well, I’ll not keep you both tonight.’ The garda stood up, nodded, and went to lift the latch of the door. Angel quickly aided his release out onto the porch.

‘Is that it?’ Angel asked.

‘That’s it. I’ll call in tomorrow and we’ll catch up then.’

‘Patrick…’ Angel called out before the garda had reached the hedge.

‘I saw her you know. Margaret. Today. Out on the road.’

‘What time would that have been?’

‘Four, five hours ago.’

‘She was probably on her way up. ’Tis a pity you didn’t catch her first, huh?’

‘Then you’re sure it’s…’

‘She has previous. That’s all you need know. Just keep to the village for the weekend now till the forensics are done. Goodnight now.’

When he returned to the house, Jess was curled up in bed. Angel quietly closed the bedroom door and went into the kitchen. He stood with his back to the fire and began to consider the day: nothing had gone right from the start of it. Maybe the whole project had been a mistake and they would have been as well to have sold the property when he’d inherited it. But they’d had this mad idea of a life in the country. Maybe it was he and Jess; maybe they were just wrong in the place, like the Swedish mink. Why had he not called out to Margaret when he saw her in the road? She was alone, and not shouting her usual venom at Jack. He should have guessed something was amiss.

He went out with his big stick to the side field. He walked along the lane-way to the edge of the land, passed the desolate-looking black field, all darkly ploughed and waiting to be sown, the tall grasses on the rim of it kissing in the crosswinds. He looked over towards Henry’s and saw a flashing light from a television screen spill onto their flat dark lawn. He looked up at the black pines and turned to face the long width of emptiness over the ravine down to the river. In the water he saw his reflection and the transillumination of his eyes; they glowed. He took a gulp of the sleet-laden air and thought of poor gormless Jack who had now lost his wife. It racked him. He thought of Jess, and of all the precious time he’d missed with her this past year. The wall can wait a while, he told the land, and turned and walked quickly towards the house.

The Badminton Court

The window of my room faces a tall hedge and an ancient oak, home to a kestrel and her two chicks. Beyond Redwood are hills, the edge of a winding silver lake. As I observe its gleam curl around the estate, I know instantly that I do not have to cross the lake to find what I need, that happiness is a small question, easily answered.

Summer. The smell of cut grass, the faint odour of plimsoles. Throughout the house the unmistakable bouquet of hemp. Fourteen acres of manicured gardens and lawns. The sky an azure spell. Clouds that are bird-shaped: an eagle, doves, buzzards. There is a palpable sense of waiting on the badminton court below, a silence soon to be punctured by bat whacks, whistling shuttlecocks and the swish of serge skirts.

I look down at the court, the sun scalding the lawn, the bullfinches gathering in the gods of the low, long hedge to watch the morning game. I know I’ll be here for a while. Then music: Saint-Saëns, Joy Division. I know what she wants. I hear the front door slam. I go to the games room and change into the maroon-coloured gown. I am here to play. I am here to help her forget. I am here to help her die.

This is Redwood House, Suffolk. Constable country. Miranda is seventeen. She is thin with shorn blonde hair, and is altogether the most disarmingly honest person I have ever met. Reveals to everyone precisely what her illness is, gives them diagnosisandprognosis. Brain tumour. Malignant. Grade four. Three to six months. I am used to a more guarded (though perhaps ‘duplicit’ is a better word) environment. My father’s cagey manoeuvres, his dubious schemes, his admired business acumen. My presence is itself the settlement of his debts to Miranda’s father.

Apart from Frances and me, she is alone at Redwood. Her father is off on some protracted business trip; her mother, never discussed, is, I think, barely known to her. The herbal preparations, the meals, the thrice-weekly trips to the clinic, are left to Frances.

Further to the south of Redwood there is another property, with a small boathouse: South Lodge. Lavender hedgerows, saxifrage-covered rocks, an assortment of mangy cats and kittens. This is Inshaw’s place. From this land he watches us. When we play he pretends he is out gathering mushrooms or repairing the corrugated roof of the boathouse. Sometimes I see his dark, deliquescent eyes follow the shuttlecock back and forth over the net. He is a presence in the game; triangulates it. She tells me to ignore him.

I have become, within weeks, father and mother to her. Father, mother and more.

Dinner. Frances has prepared salmon and marinated tuna and Miranda wants to teach me how to use chopsticks. She rises, comes towards me. The sick smell of her as she bends over my shoulder; death is in her breath. I have forgotten she is so ill. It is easy to do: that lightness of spirit, precision of play. She drops her head on my hair. Your beautiful hair, she says, your long, dark beautiful hair. I am aware of her bones against my own tumescence and curves. She comes away, stands before me, androgynous and stark, and for a moment it seems as if each of us has been called up from the depths of the other’s consciousness. We go on like this. The days are endless, summer does not turn. Only I notice the chicks are bigger in the oak, and that Inshaw has finally repaired his roof and is sailing his boat, or I would hardly register the passing of time at all.

I bump into Inshaw in the village. I am surprised. Nice man, shy. We discuss Miranda. Poor Miranda. It isn’t fair. It isn’t right. He says he will look out for her when I leave at the end of September. I realise I do not want to leave, not ever. I think of my first night and the thoughts I’d had of escape, of secret instant escape onto the tall hedge; I consider how fortunate it was I did not give in to those thoughts. The encounter with Inshaw has startled me. The sudden reality of the situation, a splint of cold glass in my skull.

She says little at breakfast. The evening before she had been on fire. Rapid, erratic thoughts, unfinished sentences, sentences that unravelled, ending in lacunae, gibberish. She had been rude, her inhibitors obstructed by that thing, growing, multiplying inside her. Tumour talk, Frances calls it. She has some toast, a thimble of marmalade, tea. I know she wants a game because she is dressed in the maroon gown. Worn when badminton was played as formally as tennis or cricket, the serge gowns are almost a hundred years old. They belonged to her grandmother. Miranda had found them soot-soaked in the cellar, later began to wear one as protection from the sun. Long-sleeved, cuffed, mandarin-collared, they are oriental in design. Frances says they make us seem like twins. Miranda leaves the house and I go to the games room to change. She has left a sprig of something, eglantine, by my washed and ironed gown on the bench. The sight of it horrifies me.

Our last game. Her play is at half-speed. Her co-ordination off. She is all over the place, drops the shuttlecock. It is tragic to watch. She observes the weakness in her own swing. Summons all her strength and it is poor. Flails about with the racket, pretends there is something wrong with it, but her racket is fine. Essays an awkward thrust and teeters. She is being milked by that thing. It is unspeakable. Eventually she gets a whack. The shuttlecock is not so much launched as massaged by the catgut. She continues, laughs it off, but she cannot get the shuttlecock to cross the net. The sky is a bowl of darkest mussel-blue. Then rain. She runs inside. I hear music: Joy Division, ‘Dead Souls’. The curtains are drawn. I smell burning herbs, cannabis. She is in pain. I know what I must do. I walk to Inshaw’s. He offers to sail the boat for me but I assure him I am a seasoned navigator. It is untrue. My upbringing proves fruitful for something: Inshaw lends me his boat for the day.

Miranda and I sail on the silver lake. The day turns bright and humid; a heron wades through the dark-green mud of the bank, water lilies spin with the current. The motor is off and I oar through syrupy, calm conditions till we come to the bend, continuing through a wider willow-lined stretch, still on the estate. Here the wild flowers are in bloom, the eglantine, meadowsweet, great burnet. Low clouds of red admirals skim the side of the boat, their fat gravid centres covered in wet fur. In fields I see bales of hay, barley being harvested. Her face has tilted to one side. Her freckled, yellowing face is beginning to develop a pronounced drop, with drooped jowls, and she drools when she speaks. In her eyes some recognition of what is happening to her. I will always be convinced by that look. I try to tip the boat. It is a struggle. The boat shudders, takes a while to capsize. She screams, splashes about. I swim towards her, hold her, our bodies small and snug in the water. My plan is to swim back once she has gone under, but I can’t leave. She clings to me, accepting and placid.

Twenty-four hours later I wash up against a bank. I am alive, and later wake up in hospital. Miranda floats to an island in the river, into a swan’s nest. She is so white two diving teams fail to spot her wound around the reeds and tall red crocus.

Twenty-two summers pass. The world is a changed place.

Redwood belongs now to Inshaw. He grants me a walk through the estate whenever I come here. Around the mile or so of angular hedges, the ancient oak and badminton court, where, sometimes, I think I hear the wind fluting through plastic.

Once he asked if I was happy. Before I had the chance to reply, he said his own life had been good and prosperous, but hardly happy. Mine was the same, I said. What is happiness? he asked, as if I knew any better than he. I pondered on this. For me, I said, happiness is two girls playing badminton under an azure sky with clouds that are bird-shaped. Those summers were best, he replied, when I used to watch you play. It occurred to me then, that for nearly a quarter of a century we had both been sustained by a few intoxicating memories squirrelled from our youth. I told him it was high time we lived a little. He agreed and told me then of his plans to flatten the court. I remember that as I walked towards my car, parked beside the silver lake, I had the distinct and certain feeling I was being watched.

1975

As the light weakened, Mr McCourt pulled open the velour drapes and lit the vanilla-scented candle. He had just said goodbye to his youngest daughter, and watched as she crossed the road to catch the airport bus. His children had been coming and going for a long time, perhaps twenty years, but he’d never gotten used to it, and ‘goodbye’ had become increasingly difficult.

‘We’re thinking of buying the white bungalow,’ he had heard her say throughout the four days; he knew she hadn’t even arranged to view it.

‘You’ll not be able to settle in if you leave it too long.’

‘It’s my town isn’t it?’ she had replied.

He watched her stand stiffly by her black trolley, her long red hair jetting out of a high ponytail. She did not look across at him standing behind the flame in the otherwise dark room. He must, he thought, be visible behind the nets in the dusky evening. Nor had she so much as glanced at the white bungalow. She reminded him of his wife with that hair and her petite frame, but something tight and of the city clung inelegantly to her. He had not fully believed her work-attributed reasons for rushing back to London.

He thought that maybe he’d talked too much during the days he’d spent with her; he thought of what his son, Francie, had said: don’t try too hard with her, don’t take time off for her. As far as he knew she hadn’t even been near Crowe Street.

Hehadtaken time off for her. Almost in anticipation of her visit, he had recently brought in two new girls to help Bridie, his chief baker. Bridie had come home after thirty years with big plans for her own shop, only to have her husband run off with a girl half her age after their first month home. (He had felt sorry for her; she was often sour-faced but good with the women.) It had been his hope, until recently, that Francie or one of his daughters would run the shop with him. It had happened at Daly’s and Duffner’s; siblings working together in their respective shops, both families exuding a soft and enviable pride. Once he had Francie with him for a whole summer; the girls came sporadically during holidays but that had been the extent of their working together as a family.

The bus was late. Perhaps she would cross to the house and stay another night. They could listen to the Lena Martell records, or to Geraldine O’Grady, and he could tell her the stories about the farm, stories about the Channonrock families and O’Hara and his own scrapes at the border in ’69. He hadn’t told any of them the stories in years, he thought. Nor had they asked for them. Further evidence, if he needed it, that they’d all managed to sever themselves from their past. The realisation had come as quite a shock to him, about five years ago.

In London, his wife had dragged the girls to Irish dancing on the other side of the city in Finsbury Park. He had taken all four of them to Irish language, flute and recitation classes at the Irish Centre in Quex Road in Kilburn, twice a week. They had done so in anticipation of returning, building a home and business back in the town; and he didn’t want his children to forget and grow up English. (The South London accent was enough for him; had he had any say they would have been trained to adopt his own sharp Monaghan spurt.) It had taken much longer than planned to save in London, and by the time he’d brought them back, the so-called ‘Irishness’ they’d been inculcated with stood out as artificial; an outmoded thing in the prospering town.

‘Irish culture is alive and well and living in Birmingham,’ he would to say to Bridie, who knew exactly what he meant.

He watched his daughter haul on a cigarette. Of all of them it was she he worried about most. She drank too much, he thought. He wondered, as she stood in the road, looking to see if the bus was coming over the Dublin Street hill, if she’d ever forgiven him.

The Mother and Daughter Wards (as he called them) passed the window and looked in. He jumped back because he didn’t want Margaret Ward to see him. She would think it peculiar, the lights off as he stood there looking out from behind a lit candle. He found her stern but also striking with her black-black bouffant hair and kohl-lined eyes, and he felt a little afraid at the thought of explaining himself to her. If she had caught sight of him she would probe him for sure. All the same, she was gracious, and uniquely considerate, too, in that she had had a memorial mass said for his wife in The Friary every year at Christmas on the anniversary of her death. But take-me-take-my-mother was written all over Margaret and he wasn’t ready for that level of commitment. He moved to the side of the window and momentarily took his eyes off his daughter, now fretfully pacing, to watch Margaret Ward’s pencil-skirted rump sway with maturity and confidence as she walked her mother into their own house, three doors up.

‘Why don’t you sell up, Mr McCourt? That’s what you should do. Travel while you still have the time,’ Margaret had said when he told her about his children’s lack of interest in the business.

‘Don’t you think the town’d miss me, Margaret? Wouldn’t they miss my buns?’

‘They would, I suppose. I’d miss your Tipsys. Mother would miss your Chesters, that’s a fact.’

‘This is it, Margaret. I couldn’t sell up even if I wanted to because I know there’s no one makes as great cakes asThe Home Bakery. And until there is, I feel I just can’t sell.’ He had no intention of selling the shop and, at this stage of his life, had little interest in travelling beyond the town.

He checked his watch. The bus was now twenty minutes late. He thought he caught sight of his daughter looking over at him through the window. He waved but she didn’t wave back. He saw then that the birdseed she’d scattered on the bird-table had attracted a host of peach-breasted chaffinches, bullfinches, some siskins and a pair of collared doves, but the family of robins would not come down from the juniper tree. He had known this would happen.Heonly ever laid stale breadcrumbs but, as she’d bought the seed especially, he kept quiet about it. The male at the front played sentinel as the brood waited in the nest making ticking sounds. They’re cute enough, he said to himself. The robins would swoop down for stale bread because it was of little interest to the bigger birds that pecked at it as a last resort, preferring the berries, worms, gifts of other gardens. He liked to think that it was their closeness and joviality as a brood that impaired their ability to attack and mark territory. They were his favourites, and he made a mental note to go out and put down breadcrumbs once the bus had come and gone.

They had not always had such a variety of birds. When they first bought the house there had not even been a proper garden, just scrubland out the back, concrete at the front. He and Francie had rolled out a new lawn over the dug-up concrete. They had planted flowers, shrubs and a laurel hedge, and sowed a small area with vegetables.

After the garden, he’d put almost all of his time into the business, missing much of his children’s growing-up. Somehow he thought they would understand his occasional moodiness, his silences, as the consequences of running a demanding, successful bakery. He would start at four in the morning with the breads. By six he would be ready to blend icing. He would then pour the icing into various spacklings and place these in the fridge. Black icing was required for the lettering; lemon, pink, blue, green and gold were used for the buns and birthday cakes; navy for the children’s cakes – and this had to be prepared slowly as it was made from a delicate combination of black and red Wilton colouring. Sometimes he’d watch his over-heating hands ruin his handiwork and he’d have to plunge them into ice water. Then he would bake pastry: choux for the eclairs, flaky for the cream slices, short-crust for pies, tarts, followed by the mixes for the Madeiras, angel-food cake, gingerbread, lemon cake and various puddings. His creams consisted of mock, whipped, clotted, butter-starch and Chantilly, and an hour before the shop was due to open he made the pink and white meringues. His schedule was relentless, and though he experienced occasional surges of pride and satisfaction from his efforts, it was, in the main, a long, hard graft. That his children had never appreciated this punishing schedule was plain now. He had nonetheless been surprised to learn of their peculiar resentment towards him; they seemed to think he’d given too much time to the business during the difficult years after their mother’s death.

The candle flickered, crackled on a fallen hair. He thought of the bomb. Planted in the blue Hillman Hunter outside Kay’s Tavern in 1975, the year he lost everything. In 1975 he had handpicked all ingredients and supplies himself, baking the stock out the back and serving alone in the then staff-less shop. He bought some breads in from McCann’s and McElroy’s but mostly made his own: soda farls, brown sodas, white sodas, yeast browns and whites, and once a week a black rye with walnut and caraway seed. It was Mr McCourt’s fervent belief that had he not been alone in the shop on the day of the bomb his premises would have been spared.

His thoughts drifted off to the unearthly light that had hung over Crowe Street that Christmas afternoon as he watchedThe Home Bakerymelt to the ground like warm lemon icing.

‘We’re lucky the town hall didn’t go too,’ Jack Daly had said. ‘Blew the doors clean off. Bits of them oak doors flying like leaves, so they were, Mr McCourt.’

‘It’s a horrible thing,’ he had replied, ‘horrible for someone to do that to people.’

‘That’s their response to Sunningdale*you know. You of all people, McCourt, should be doing something about that now.’

Daly’s unsubtle call to arms still haunted him. What he had done at the border in ’69 had been admired, but any man might have done that; the bombing of Kay’s was different, for it signalled the escalation of a dirty and protractedwar.

Mr McCourt recalled that it had been a strange, overcast day from the outset. He remembered the full moon that had hung ominously by the outermost tip of Cooley, as if it possessed some significant bearing on the awful proceedings below. For many, the day had become a blur; for McCourt, a detailed recording he could replay with exactitude.

He had tried hard to save the shop.Over here, over here, he had screamed to the firemen, indicating the fire raging in his kitchens and all along the outer wall. He had watched them carry out two bodies, and over twenty injured from Kay’s. They had looked shattered: Joe and Jaxy. He knew them both, and he had never seen either of them look so bloodless and horrified.We have you Mr McCourt. You’re next, they assured him. He remembered the flames finding fresh force in the pub, just as the Town Hall foyer exploded. He recalled the eerie smell of gas and the realisation then that he would probably lose the bakery.

With the detailed images of that day, came also its hellish sounds. He recalled the bells in St Patrick’s rumbling dissonantly as thin cracks wired the plaster in the shop wall right in front of him. Within seconds of the first blast, large wedges of two-by-fours, complete with flames, nails, melting turquoise paint, had crashed through the pastry display and onto the marble counter, catching the thick pile of wrapping tissue. He had even tried to quench the fire with his own shop coat. Open tins of oil, lined up in a row against the kitchen wall, caught the flames with a heavy fizz, and the entry to the ovens area collapsed outright. He had used the small fire extinguisher he’d bought off the travelling salesmen, but it had been no good. The emission dry and wispy.

He seemed to be in a daze as he stared out at the street’s glowering aftermath. Beneath the platform of the foremost engine, a red barrel had been rolling up and down a long stray plank. The barrel made a relentless, rhythmic din as it massaged the half-burnt length of wood. The rattle fixed in his ear, gave a rhythm to his thoughts:look at that barrel, like a sea-saw rattling, will it ever roll loose. Over and over, like some macabre rhyme. Beside the barrel oozed puddles of petrol with rainbow-coloured rims. Loose pieces of corrugated sheeting were strewn across the dark, wet streets, and occasionally gusts of wind would clatter them against the sides of fire engines. He recalled that water had dripped from eaves, even though it hadn’t rained.

Nor would he ever forget the pervasive smell: wet smoked timber and ash mixed with the distinctly bitter smell of gelignite. He had smelled that combination before, and it was, he thought, by far the world’s bitterest smell.

He recalled the devastation that had quickly collected around him: the pavements had turned pure charcoal. By the door of the shop lay the remainder of a white leatherette car seat. Two brown, soot-stained platform boots lay abreast by the drain. He remembered wondering how on earth two matching boots had come to be so conveniently together. A woman’s black, feathered hat and one black glove lay in a pool of bubble-topped grey water, swirling in a pothole. Ahead, gardai were walking around the remains of the blue Hillman Hunter, taking notes and sealing the area off with yellow plastic tape. And then the bizarre sight of a man who had wandered out of the Town Hall with a blown-off hand, having to be taken to hospital in the back of a truck with a big blue sign forElliott’s, The Fishmongersstencilled on the side.

But, he recalled, the rattling barrel had continued to draw him that day; its hypnotic sound, its eye-catching shade – the colour of his wife’s hair.

The doorbell rang. He had not even heard the clack of the garden gate. He quickly looked across to see if his daughter was gone. Twenty-five minutes had passed, and still no bus. He watched the jet of smoke rise into the cold air from her pursed mouth. She sat on her trolley, held her coat in tightly with one arm, as if her stomach ached. A man tried to speak to her, but she remained almost rudely mute. She had always been his least talkative daughter. The rest of them usually drove him mad with their chatter. He went to the door. It was Bridie. He was surprised to see her.

‘I left the shop early, Mr McCourt,’ Bridie said, quietly.

‘Do you want me to go in to the girls?’

‘No, not at all. It’s near closing now. Anyway, you’re off and that’s it. We do need cornstarch though.’

‘I’ll see to it.’

‘Grand. I just wanted to come up and ask if I could have the day off Monday.’

Something was wrong. Bridie was an attractive woman: pale as milled flour, but because of her persistently poor self-esteem, she did not radiate the beauty that was evidently hers. She wore no make-up, never seemed to get her wiry grey hair coloured or styled, and habitually wore thick beige nylons with small eyeholes stopped from cobwebbing entire legs by layers of clear nail varnish. One time he had noted a glittery blue by her right calf. He had laughed at the cosmetic tricks of his daughters, and knew that repairing nylons had long gone out with the ark. Still, he found her injured politeness magnetic.

‘Is that alright, Mr McCourt?’

‘Monday? Yes, of course. Take it off, Bridie. I’ll take over. That’s if I haven’t forgotten what to do.’

‘Ah now. You’re too modest.’

‘Planning a heavy weekend then, Bridie?’ he joked, ushering her into the front room.

‘No,’ she said quietly, ‘it’s my divorce.’

His face reddened and he turned to the window. In the more energised atmosphere of the bakery he would have been quicker off the mark and able to respond to Bridie’s frankness. But at home, this evening, his guard was down, and he couldn’t think of anything to say. He stared into the darkening street.

‘Warm fire you have going there, Mr McCourt. Would you not close the curtains and put on the light and settle up to that? It’s dark now, you know.’

‘I’m watching my wee girl, Bridie. Till her bus comes for the airport.’

‘Righto,’ she said, gazing towards the window. ‘Maybe I’ll bring you a pie then, later. Would you like a pie, Mr McCourt?’

‘No. I’m not hungry at all.’

‘I’ll go so.’ He let Bridie out of the house. He was sorry to see her leave, but glad that he could carry on by the window in peace.

The dark clouds were staggered in short strips across the horizon. His daughter remained perched on her trolley, her bus now almost forty minutes late. He considered going to the door and calling out for a cross-traffic conversation, but then thought this would embarrass her.