Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Wissenschaft und neue Technologien

- Sprache: Englisch

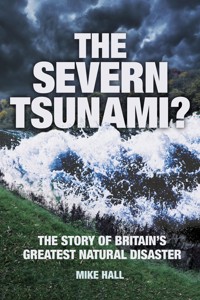

On 30 January 1607 a huge wave, over 7 meters high, swept up the River Severn, flooding the land on either side. The wall of water reached as far in land as Bristol and Cardiff. It swept away everything in its path, devastating communities and killing thousands of people in what was Britain's greatest natural disaster. Historian and geographer Mike Hall pieces together the contemporary accounts and the surviving physical evidence to present, for the first time, a comprehensive picture of what actually happened on that fateful day and its consequences. He also examines the possible causes of the disaster: was it just a storm surge or was it, in fact, the only recorded instance of a tsunami in Britain.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 233

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2013

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

In memory of the medieval carved Head of a Maiden, hacked from its stand and stolen from St Thomas’s Church, Redwick, at about 10 a.m. on Saturday, 9 June 2012. A witness to the flood disaster of 1607, what tales could she have told?

CONTENTS

Title Page

Dedication

Introduction

1. Dating and Measuring

2. Rhines or Reens?

3. Contemporary Sources

4. 1607 – An ‘Interesting’ Year

5. The Cause of the Disaster

6. Major Flood Events Since 1607

7. Gazetteer

8. What if it Happened Again?

9. The Construction of the Sea Walls

10. Some of the Eyewitnesses

11. The Monmouthshire Milkmaid

12. Other Possible Tsunamis Affecting the British Isles

13. Project Seal: Tsunamis as Weapons of War

14. A Final Prayer

Bibliography

Copyright

INTRODUCTION

‘About nine of the clock in the morning, the same being most fairly and brightly spread, many of the inhabitants prepared themselves to their affairs.’

Then they might see afar off huge and mighty hills of water tumbling over one another as if the greatest mountains in the world had overwhelmed the low villages and marshy grounds. Sometimes it dazzled many of the spectators that they imagined it had been some fog or mist coming with a great swiftness towards them, and with such a smoke as if mountains were all on fire, and to the view of some it seemed as if millions of thousands of arrows had been shot forth all at one time. So violent and swift were the outrageous waves that in less than five hours’ space most part of those countries (especially the places that lay low) were all overflown, and many hundreds of people, men, women and children, were quite devoured; nay, more, the farmers and husbandmen and shepherds might behold their goodly flocks swimming upon the waters – dead.

(God’s Warning to his people of England, printed in 1607 by William Jones of Usk, Monmouthshire.)

One evening in April 2005 my wife Linda and I, staying at her parents’ home in Almondsbury, north of Bristol, settled down to watch Killer Wave of 1607, a documentary in the BBC2 Timewatch series, giving an account of the flood that had devastated the lowland areas on either side of the Bristol Channel in the early seventeenth century. We knew that this had affected nearby parts of South Gloucestershire and we were looking forward to seeing pictures of places that we knew well.

To be honest, we were a little disappointed. Much of the programme had been filmed in those strange foreign parts on the Welsh side of the Severn Bridge. A place called Redwick, which we had never heard of, figured prominently in some of the most dramatic reconstructions, but there was virtually nothing about Almondsbury, Olveston or South Gloucestershire in general. Little did we know that in less than two years’ time we would be living in Redwick and attending the last of a series of events being held in the village to mark the 400th anniversary of the Great Flood.

Redwick Church.

Killer Wave of 1607 introduced to the wider public the theory proposed by Professor Simon Haslett and Dr Ted Bryant that the flood was caused by a tsunami. The programme had been filmed during the summer of 2004 and by the time it was broadcast its central thesis had been made poignantly topical by the awful events of Boxing Day in South East Asia and everyone watching knew what a tsunami was.

Some academics dispute Haslett and Bryant’s conclusions, preferring to believe that the flood was the result of a storm surge. I am not a specialist in this field but I will try to summarise the evidence for both explanations in this book – which would not have been written if it had not been for the interest generated in the subject by the tsunami theory. I am grateful to all those (too numerous to list here) who have given me practical help and advice. Any errors of fact or interpretation are, of course, entirely my own work.

Mike Hall, Redwick, Monmouthshire, 2013.

Illustrations: All photographs are by Mike or Linda Hall unless otherwise stated. I am particularly grateful to Richard Jones for allowing me access to the pictures used in the Flood 400 exhibition in 2007 (and for his advice and comments), also to Jane Gunn of Wedmore for her pictures of flooding on the Somerset Levels. The postcards used are from my own collection. Images sourced from Wikipedia are reproduced under the Creative Commons Attribution Share Alike licence. Finally, I could not have managed without the help of Linda and my younger daughter Elizabeth (who understand the minds of computers) in sorting the images for publication.

1

DATING AND MEASURING

Exactly when the flood happened has been a source of confusion over the years. It is usually referred to as the 1607 flood but many of the flood marks and other contemporary sources have it dated at 1606. The date of the event is given as 20 or 30 January, which makes marking the anniversary on the correct day problematic.

In Roman times the start of the year was reckoned to be the Ides (22) of March, a date infamous for the assassination of Julius Caesar. The Roman Catholic Church followed this practice until the sixteenth century and the fact that even now the tax year begins in April rather than January is a reminder of how things used to be. It took a while for the new system to become accepted, especially in Protestant countries. In England and Wales the New Year officially began on Lady Day (25 March). At the time of the flood, local people would have considered that they were nearing the end of 1606, while more ‘up-to-date’ folk in London and on the continent would have said it was 1607.

The other factor is the change from the Julian calendar to the Gregorian one. The old calendar had allowed for the fact that a year is actually 365¼ days long by introducing the concept of a Leap Year every four years, with an extra day on 29 February. However this adjustment was not precise enough and over the previous 1,500 years the calendar had got progressively out of phase with the seasons so that festivals such as Easter and Christmas had somehow drifted from their rightful place. Pope Gregory proposed to deal with this anomaly by declaring that in future, three out of the next four ‘century years’ would not be a leap year. 1600 was a leap year but 1700, 1800 and 1900 would not be. To get the calendar back in line with the seasons he decreed that ten days would be taken out altogether so that 4 October would be immediately followed by 15 October.

This new Gregorian calendar was introduced in Italy immediately, but once again other countries were slow to bring in the change. It was not done in England until 1752 when it famously led to riots and the slogan ‘Give us back our ten days!’ In this instance the Scots were ahead, introducing the new calendar in 1600, but even when their king, James VI, moved south in 1603 to become King James I of England (and Wales), the change was not made.

To sum up: the Great Flood occurred on 20 January 1606 (old style) and 30 January 1607 (new style).

The confusion has not gone away. In 2007, the Flood 400 organisers put on a ‘Wave of Bells’ to commemorate the anniversary. Bells were rung in all the churches along the Welsh coast, from Rumney in the west to Chepstow in the east. This event took place on 20 January and I remember being told at great length by a steward in one of the reconstructed houses at the open-air museum at St Fagans that they should have done it on 30 January. However, there was also a Service of Commemoration, using words from the Prayer Book of the time, on 30 January, so the organisers of Flood 400 wisely had both dates covered.

In his West Country Weather Book, which was published in 1995, author Barry Horton mirrored the uncertainty. He had looked at accounts of the flood in John Latimer’s Annals of Bristol (1900–8), William Adams’ Chronicle of Bristol (1910), G.E. Baker’s article in Bedfordshire Notes & Queries (1884) and T.H. Baker’s Records of Seasons, Places and Phenomena (1911) which gave a variety of permutations of date. ‘As it was such a major event and many of the details are so similar,’ he wrote in bewilderment, ‘I can only conclude that these four writers have their years mixed up and it is the same event. Ironically, two of the writers who disagree on the year, do actually agree on the date of 20 January’. It would seem that Mr Horton did not know about Pope Gregory!

Finally, there is the similarly vexed question of measurement of distance. In 1607 (or 6) the metric system had not yet been invented. Inches, feet, yards and miles were the units used in the contemporary accounts and by people at the time. For me, to use metric would be perverse in the extreme.

I was not, despite what my former pupils might have believed, around at the time of the flood, but I am old enough to think more naturally in feet and inches. However, modern scientific research papers use the metric system and many readers will be more comfortable with it. I have compromised by using the same units as my sources while giving the alternative in brackets, which I hope will satisfy everybody!

2

RHINES OR REENS?

The flat low-lying fields of the Somerset Levels and of the similar landscape on the Welsh side of the Severn Estuary are criss-crossed by a network of drainage ditches. In Wales these are called ‘reens’. In Gloucestershire and Somerset the name for them sounds the same but is confusingly spelled ‘rhines’ or even ‘rhynes’. This is a trap for the unwary, not least the Lancashire-based folk band who recorded an LP of songs to mark the 300th anniversary of the Battle of Sedgemoor in 1685. It was only after the record went on sale that someone pointed out to them that the word should not have been pronounced the same as the river! They probably used a rather different short word in response. I have used reen when referring to these channels on the Gwent Levels and rhines when referring to those on the English side.

A rhine near Olveston, Gloucestershire.

3

CONTEMPORARY SOURCES

Researchers are fortunate that the flood happened when the country was more literate than at any period since the Romans. It was the time of Shakespeare’s plays and the King James Bible. There were no newspapers but increasingly pamphlets reporting and commenting on current events were being produced in London. St Paul’s churchyard had become a focus for the printing of these and many of them had an apocalyptic religious flavour. Typical of these was God’s Warning to His People which began with ‘many are the doom warnings of destruction which the Almighty God hath lately scourged this our Kingdom with; and many more are the threatening tokens of his heavy wrath extended towards us’. Moral lessons were pointed out, such as ‘many men that were rich in the morning when they rose out of their beds were made poor before noon the same day’. For the writers of these pamphlets, the disaster was seen as a judgement by God on his sinful people.

These publications hardly had snappy concise titles. The full title of God’s Warning to His People continued Wherein is related most Wonderfull and Miraculous works, by the late overflowing of the Waters, in the Countryes of Somerset and Gloucester, the Counties of Munmoth, Glamorgan, Carmarthen and Cardigan with divers other places in South Wales – which says it all, really! Newes out of Summerset-shire was ‘a true report of certaine wonderfull ouerflowing of Waters now lately in Summerset-shire, Norfolke and other places of England: destroying many thousands of men, women and children, overthrowing and bearing downe upon whole townes and villages, and drowning infinite numbers of sheepe and other Cattle’. Lamentable Newes out of Monmouthshire had a similarly long-winded full title. They shared the same woodcut illustration, a scene reputedly showing the tower of Nash Church surrounded by floodwaters that has become the defining visual image of the event.

Artist’s impression of the woodcut that appeared on a contemporary pamphlet titled Lamentable Newes out of Monmouthshire in Wales.

Other important written sources include a vivid description of events in North Devon written by Adam Wyatt, the town clerk of Barnstaple, and details from the town’s parish registers. The registers of Arlingham in Gloucestershire give a dramatic account of both the saving and loss of life, while the Vicar of Almondsbury’s report includes significant meteorological information. The diary of Walter Yonge of Colyton and Axminster, though hardly an eyewitness, also gives some detail absent from other sources, as does Camden’s Britannia and some poems by John Stradling in his book Epigrams.

All these sources have been pored over by competing academics, searching for that vital clue to help determine the cause of the event. For example, the description in God’s Warning …, quoted at the beginning of this book, is seen by many as evoking visions of an advancing tsunami off the coast of Thailand in the bright sunshine of 26 December 2004. There are full details and extracts from these documents at www.website.lineout.net which seems to be the most comprehensive source on the internet for information on the flood. Where I have quoted from these publications, I have modernised the spelling and punctuation for ease of reading but this site has links to the original text for those who need it.

Many churches in the affected area have near-contemporary memorials. There are flood marks at Peterstone, Nash and Redwick in Monmouthshire, a brass plaque with rustic lettering at Goldcliff, a stone one at St Brides Wentloog and a board at Kingston Seymour in Somerset. A second memorial there gives details of a subsequent flood which led the inhabitants of nearby Yatton to take out a lawsuit to try to recoup their losses of crops and livestock after the sea wall gave way and saltwater covered their fields. Many of the places flooded in 1607 had suffered the same fate before and would do again, not least in the Somerset Levels, much of which was under water at the time of writing.

4

1607 – AN ‘INTERESTING’ YEAR

It is said by some (though disputed by others) that the Chinese have a curse which reads ‘may you live in interesting times’. For many, 1607 was an ‘interesting’ year. It began with a financial crisis on 13 January: the Bank of Genoa crashed after the announcement of national bankruptcy in Spain.

The same month, ships waiting to sail from England to America were prevented from sailing by stormy weather at sea. Later in the year, colonists were to make landfall on the coast of Virginia, move up the James River and establish Jamestown, the first permanent English settlement in the New World.

Jamestown was, of course, named after King James I, who had been King of England since 1603, having previously been James VI of Scotland. In 1605 he had survived the attempt on his life in the Gunpowder Plot of Guy Fawkes and his fellow conspirators. In 1606, Shakespeare’s Macbeth was published, a work so ill-omened that even today members of the acting profession dare not speak its name.

And then there was the Great Flood …

Appledore in North Devon was probably the first place to suffer the fury of the giant waves that terrible morning. If there was anyone in the steep, sloping churchyard at Instow on the opposite side of the river, they probably would not at first have paid much attention to the white water over the bar at its mouth – that would have been a familiar sight. But this wave just kept on coming, growing higher and more destructive as it came towards the shore. Later, the pamphlet More Strange News would describe how ‘many houses were overthrown and sunk’, as the wall of water broke over, demolishing them and ‘a ship of some three score tons, being ready to hoist sail and being well-laden, was driven by this tempest beyond all water-mark and is never likely to be brought back again’. The wave struck perpendicular to the shore and then peeled along it before inflicting considerable damage at Instow, where a new jetty had to be built after the disaster.

Using the evidence of date stones, Haslett and Bryant (2004) suggest that the oldest surviving building on the seafront in Appledore is Port Cottage, built around 1750. Around Irsha Street and the Royal George pub, the area that took the full force of the wave as it struck, there are no older buildings. At Instow, it is probably Sailors’ Rest Cottage (dated 1640, thirty-three years after the flood). They conclude that ‘the events of 1607 may have lasted a considerable time in the folk memory … and reconstruction might have been understandably slow to follow’.

The onrushing waters followed the Taw Valley inland to Barnstaple. Robert Langdon, the parish clerk, described how ‘there was such a mighty storm and tempest from the river with the coming of the tide that it caused much loss of goods and houses, to the value of a thousand pounds … The storm began at three o’clock in the morning and continued till twelve.’

View from Instow churchyard.

A document in the North Devon Record Office (ref: NDRO.B12/1), quoted by Haslett and Bryant, states that there was:

A very great flood. Water came up in Southgate Street and in Wilstreet. It came to Appley’s fore door and run out through the house into the garden there and made great spoil. The water flowed more than half way up Maiden Street and then went into their houses. Also it came up at the lower end of Cross Street so far as Mr Takles hall door. The tombstone upon the Quay was covered clean over with water – by report it was higher by five or six feet than ever remembered by those now living.

West of the Quay, a house belonging to a Mr Collybear was badly damaged, as was Mr Stanberie’s to the east. Nearby some of the first deaths took place:

[the wave] threw down the whole house wherein James Frost did dwell, whereby himself was slain with the fall of the roof and two children slain with the falling of the walls. All the walls between that and the Castle fell and the top of the house of the horse mill began to cleave asunder and likely to have fallen down if the Spil[way]l of the Mill, which was very strong, had not supported.

What happened in Barnstaple is well documented. Besides these accounts of the disaster, there are two others – by the town clerk, Adam Wyatt (Somerset Record Office, SF 4051) and one Tristram Risdon, writing in 1620. These will be referred to later.

Meanwhile, the monster waves were also wreaking havoc on the Welsh side of the Severn Estuary. In a matter of minutes, the beach near Ogmore Castle in the Vale of Glamorgan was engulfed in rocks and boulders in such a way that researchers in the twenty-first century concluded that a tsunami must have been responsible. Elsewhere, cliffs were rapidly eroded by the force of the water. One of these places was Sully, west of Cardiff, where the narrowing of the Bristol Channel would have constricted the wave and forced it to increase in height, becoming even more dangerous. At Aberthaw, now the site of a power station that is a prominent landmark seen from shipping in the estuary, the recently built seawall was, according to the poet John Stradling, ‘overcome and wholly torn apart’. The previous year, Stradling had written a poem about this as ‘constructed for the containment of the Severn, a herculean labour completed within five months’.

At Cardiff, St Mary’s Church, which stood beside the River Taff, was another victim. A contemporary chronicler wrote that ‘a greater part of the church … was beaten down with the water’. As Dennis Morgan wrote in Discovering Cardiff’s Past, ‘from this document arose a myth that the flood spelt the end for the mother church’. Speed’s map of 1610 shows the church more or less intact but he notes that the river was ‘a foe of St Mary’s … undermining her foundations and threatening her fall’. It would appear that the flood in 1607 removed a corner of the churchyard and the townspeople subsequently preferred to spend money on St John’s, which was in a more secure location towards the castle. St Mary’s was used less and less and was further damaged during the Civil War. By 1678, the central tower had collapsed through the roof and the building was a mere shell. Burials continued in what remained of the churchyard until 1707 and, Morgan adds, ‘children were baptised in the ruins as late as the 1730s’. An outline in lighter stone on the side of the Prince of Wales pub in Wood Street (near the Bus Station) is believed to mark the approximate position of where the church once stood.

The flood plain between the town and the Bristol Channel was inundated. The water overtopped the ancient sea banks and came as far inland as Adamsdown and Splott, areas which later became densely populated working-class suburbs but which in 1607 were almost uninhabited. The flood reached as far inland as Llandaff, four miles away, where a contemporary chronicler noted that ‘Mistress Matthews lost 400 sheep [and] no-one was spared from the impact of the deluge’.

Outline of former St Mary’s Church, Cardiff.

Rumney Church, near Cardiff.

East of Cardiff, the fields of Rumney parish (now just another suburb) were also engulfed, despite fairly recent repairs to the sea wall. The historian J.R.L. Allen quotes from the records of the Court of Augmentations for 25 February 1590/1 (depending on how New Year was defined) which said: ‘There is a wall between the sea and the lordship [manor] for the defence of the same, which wall being about two years past in great decay was by commission new made and placed more into land than it was.’ Bodies were washed up here and subsequently buried in a communal grave near the church.

In 1610, Harry Dunne of Rumney was in court attempting to prove his title to the land he farmed. Unfortunately for Dunne, according to the court records:

At the great flood and invasion of the sea in those parts, the house of John Dunne [the former owner, presumably Harry’s father] was broken by force of the said sea and, at that instant, the cupboards, chests and coffers of the said John Dunne, wherein the evidences, writings and copies of the Court Rolls which concerned the premises, were carried away in the said flood.

Eastwards again and the water reached the bottom of St Mellons Hill and had swamped the villages of Peterstone and St Brides Wentloog. We are now on the edge of the Gwent Levels, that extensive area of reclaimed land on either side of the estuary of the River Usk that suffered as badly as anywhere on the Welsh side of the Bristol Channel. Its churches to this day bear the flood marks and memorials to a force of nature, to which this area was particularly vulnerable.

Archdeacon Coxe, an antiquarian whose account of his travels through Monmouthshire nearly 200 years after the flood is a rich source of topographical and historical detail, captured the special character of this unique area. He wrote:

The ground is cut into parallel ditches, in some of which the water stagnates, in others it runs in perpetual streams called reens, which fall into the sea through flood-gates or gouts. The roads leading through these flat marshes are straight, narrow and pitched, which exhausts the patience of the traveller.

In a paragraph that may reflect the legacy of 1607 he adds, ‘these marshes, being only inhabited by farmers and labourers, contain very few houses and cottages … In former times the population must have been considerable, because the churches are large and capable of containing great congregations, though now reduced to forty or fifty persons’.

Lamentable Newes out of Monmouthshire and other pamphlets contain a number of incidents that are said to have happened in Monmouthshire during the Great Flood. Most of these would have happened here on the Levels but cannot now be precisely located. One example is the story of ‘Mistress Van, a wealthy woman who lived four miles from the sea who, although she saw the wave approaching from her house, could not get upstairs before it rushed through and drowned her’. Some later writers place her at Llandaff but another source suggests the location as being near Marshfield, Newport. The Lewis family of Van near Caerphilly were well known in South Wales in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. The website of the National Library of Wales (www.llgc.org.uk) describes the family’s distinguishing features as ‘a lengthy pedigree and a marvellous aptitude for the acquisition of property’.

Pamphlet readers were told of ‘a maid child, not passing the age of four, whose mother, perceiving the waters to break so fast into her house, and not being able to escape it, and having no clothes on, set it upon a beam of the house, to save it from being drowned’. This tale reads like a biblical miracle, for it goes on: ‘And the waters rushing in a pace, a little chicken as it seemeth, flew unto the child and was found in her bosom when help came to take her down and, by the heat thereof, as it is thought, preserved the child’s life’. Another heart-warming tale from the county concerns …

a little child affirmed to have been cast upon land in a cradle with a cat, the which was discerned (as it came floating to the shore) to leap from one side of the cradle unto the other, even as if she had been appointed steersman to preserve the small barque from the waves’ fury.

Yet another miracle escape was achieved by the Monmouthshire man and woman who …

having taken to a tree for their succour, espying nothing but death before their eyes, at last (among other things which were carried along) perceived a tub of great bigness to come nearer and nearer unto them, until it rested upon the tree wherein they were, committed themselves, and were carried safe until they were cast upon the dry shore.

The hero of the hour in Monmouthshire must have been the main landowner locally, Lord Herbert of Pencoed Castle near Llanmartin, who, the chronicles record, ‘sent out boats to relieve the distress … himself going to such houses as he could to minister to the provision of meat and other necessities.’ Without this noble and altruistic action, many more would have perished from starvation or cold in the days that followed.

The defences of the Gwent Levels were in the hands of the Commissioners of Sewers, originally established in the time of King Henry IV and invested with powers, as historian Charles Heath put it in 1829, ‘equal, if not superior to the Sovereign’, which shows the importance the Crown gave to protecting this rich farmland. Their duty was to ‘secure the prompt obedience of tenants and landholders in repairing the first breaches or injuries of dykes and sea walls’ – but what happened in 1607 was clearly well beyond what could have been predicted.