Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Old Street Publishing

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Serie: Shortest Histories

- Sprache: Englisch

'King's supreme ability is to imagine himself into the past. The scope of his knowledge is staggering' JOHN CAREY, SUNDAY TIMES From Michelangelo to Mussolini, Nero to Meloni, Galileo to Garibaldi, here is the sparkling story of the world's most influential peninsula. The calendar, the university, the piano; the Vespa, the pistol and the pizzeria… It is easy to assume that inventions like these could only come from somewhere sure of its place in the world. Yet these pages reveal a land rife with uncertainty even as its influence spread. From the rise of the Roman Republic to the decline and fall of the Roman Empire, from the glories of Renaissance Florence to the long struggle for unification, from Europe's first operas to the world's first ghettos, Ross King nimbly charts the checkered course of Italian history. In the last hundred years, film, fashion and Fiat – once bigger than Volkswagen – have emerged from the horrors of fascism and world war. The Shortest History of Italy is a majestic sweep across three millennia of history that not only shaped Europe but the wider world.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 372

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Contents

vii

To Destine Bradshaw

viii

ROMAN REPUBLIC

264–41 BCEFirst Punic War218 BCEHannibal crosses the Alps and invades Italy146 BCERoman destruction of Carthage and Corinth91–87 BCESocial War60 BCEFirst Triumvirate founded44 BCEAssassination of Julius Caesar30 BCEDeaths of Antony and Cleopatra27 BCEOctavian proclaimed ‘Augustus’ by the SenateROMAN EMPIRE

14 CEDeath of Augustus; Tiberius becomes Emperor64 CEGreat Fire in Rome79 CEEruption of Vesuvius80 CECompletion of the Colosseum117The Empire reaches its greatest expanse under Trajan180Death of Marcus Aurelius, last of the ‘Five Good Emperors’235–284‘Crisis of the Third Century’293Diocletian establishes the Tetrarchy312Battle of the Milvian Bridge410Sack of Rome by the Visigoths452Huns under Attila invade Italy476End of the Roman Empire in the WestLATE ANTIQUITY493Beginning of the Kingdom of the Ostrogoths (until 553)568Lombard invasion of Italy800Charlemagne proclaimed Holy Roman EmperorMIDDLE AGES

831Emirate of Sicily established (until 1061)1061Beginning of Norman conquest of Sicily ix1176Lombard League defeats Frederick Barbarossa at Battle of Legnano1209St Francis of Assisi gains papal approval for his order1302Dante exiled from Florence; he begins The Divine Comedy1309Pope Clement V moves the papal court to Avignon (until 1376)1378Beginning of the Western Schism (until 1417)RENAISSANCE

1417Donatello completes his sculpture of St George in Florence1452Birth of Leonardo da Vinci1454Peace of Lodi1492Birth of Vittoria Colonna1494Invasion of Italy by King Charles VIII of France1512Michelangelo completes his fresco on the vault of the Sistine Chapel1527Sack of Rome by the troops of Holy Roman Emperor Charles V1545The Council of Trent opens (until 1563)1593Birth of Artemisia Gentileschi1632Galileo publishes Dialogo Sopra i Due Massimi Sistemi del Mondo; a year later he is forced to abjure his ‘errors’ILLUMINISMO

1734Beginning of Bourbon rule in Naples1764Cesare Beccaria publishes On Crimes and Punishments1796French forces led by Napoleon invade Italy1797End of the Venetian Republic1805Napoleon crowns himself King of Italy in MilanRISORGIMENTO

1848First Italian War of Independence1859Second Italian War of Independence1860Expedition of The Thousand under Giuseppe Garibaldi xKINGDOM OF ITALY

1861Victor Emmanuel II becomes King of Italy1866Third Italian War of Independence1870Italian troops capture Rome from the papacy1900Assassination in Milan of King Umberto I1911Italian invasion of Libya1915Italy enters World War I on the side of Britain and France1922The Fascist ‘March on Rome’; Benito Mussolini becomes prime minister1935Italian invasion of Ethiopia1940Italy enters World War II by invading Greece1943Allied invasion of Sicily and then mainland Italy1944Liberation of Rome by the Allies1945Release of Roberto Rossellini’s Rome, Open City, starring Anna MagnaniREPUBLIC OF ITALY

1946Italians vote to abolish the monarchy and establish a republic1949Italy joins NATO1956Beginning of Italy’s ‘Economic Miracle’ (until 1963)1968Beginning of the Anni di Piombo (Years of Lead)1986Beginning of the Maxiprocesso (Maxi Trial) against the Mafia (until 1992)1992Assassination of anti-Mafia judges Paolo Borsellino and Giovanni Falcone; the Tangentopoli scandal and investigation1994Media tycoon Silvio Berlusconi becomes prime minister for the first time2020During the COVID-19 epidemic Italy becomes the first country to impose a nationwide lockdown1

‘That People in Togas’: Ancient Italy and the Roman Republic

the refugee-laden boats nudge through the choppy waters as the storm blows in: fugitives crossing the Mediterranean in search of asylum. Hungry, exhausted and fearful, they have been separated from loved ones, or have buried them on the journey with hasty, makeshift rites. The dream of a new land has kept them going through the tense wait on the beach for good weather and the threatening presence of ragged strangers speaking their enemy’s tongue. They have been warned that navigation will be difficult, and that passing through the narrow strait is dangerous, if not impossible.

Now, as thunder crashes, the bow of the lead vessel yaws sharply in the swell and the helmsman breaks his oar. Helpless, they slide toward shoals rising from the foam like monstrous spines. The boat spins three times, shipping water and casting men and belongings into the roiling waves. The small fleet strains to make landfall, prows thudding over breakers. Through the lashing rain the men see a cove where they can put ashore: a stretch of calm water between vast cliffs whose tops bristle with trees. ‘Trojans, ecstatic with joy at regaining the 2dry land, / Leap from the ships and establish themselves on the sand-covered coastline.’1

So opens Virgil’s great epic, the Aeneid, completed in 19 BCE. The poem recounts the legendary tale of Aeneas and his companions fleeing the ruins of Troy and arriving in Italy – after shipwrecks and other mishaps – to become the ancestors of the Romans. Virgil’s descriptions of storm-tossed refugees washing ashore on the north coast of Africa eerily presages the European migrant crisis that witnessed hundreds of thousands of refugees from Africa and the Middle East launching inflatable dinghies and other ramshackle craft into the Mediterranean in search of a new life in Europe. Italy was a natural destination given the proximity to Libya and Tunisia of its southernmost border and the islands of Sicily and Lampedusa. In 2015, more than 150,000 migrants arrived on Italian shores, with almost 3000 more dying en route in shipwrecks and drownings. A year later, more than 180,000 arrived on boats from across the Mediterranean.

The social, political, economic and cultural effects of the crisis on Italy still remain to be determined. However, the country’s most powerful myth of its origins involves, as Virgil shows, migrants from a war-torn land arriving on Italian shores and becoming, thanks to Aeneas’s illustrious descendants, ‘the masters of all in existence’, that is, ‘that people in togas’ (as Virgil proudly describes them).2 The mastery of the Romans is difficult to overestimate. First under the Republic, then during the Imperial period – taken together, a span of almost a thousand years – the Romans were to make the Italian peninsula one of the world’s greatest and most influential centres of political and cultural activity. A thousand years later, during the Renaissance of the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, the peninsula would once again become the seat of a splendid civilisation. Finally, 3Italy has been, for almost 2,000 years, the seat of Christianity in the West – something else that has placed it at the epicentre of Western civilisation.

This is a history of, in the first place, a geographical entity in which, over the millennia, many different societies and cultures have lived. Certainly, Italy always was, and still is, a well-defined geographical entity (albeit with, as we shall see, some grey areas). Few countries have their borders as clearly marked by natural features. Italy is known for good reason as LoStivale (The Boot), its distinctive profile shaped by the Alps in the north and the three seas (Adriatic, Ionian and Ligurian-Tyrrhenian) surrounding it. Few countries, too, can boast the natural beauty and (mostly) agreeable climate, making it what the poets Dante and Petrarch both called ilbelpaese (the fair country), and what a Greek historian, writing in the first century BCE, called the ‘country abounding in universal plenty and every charm mankind craves’.3 But Italy has always been much more than its mountains, shores, rivers and plains. It is defined and shaped more emphatically by the wide and diverse range of people who have been born and lived there, or indeed, like Aeneas and his fellow Trojans, moved there from elsewhere. This is a story that I hope will do justice to at least a few of them, and that will show how identifying ‘Italy’ and the ‘Italians’ is inherently more difficult than spotting the telltale boot-shape on a map of the world.

*

Virgil’s account of the settlement of Italy is not a complete fiction. Parts of Sicily and the southern Italian mainland were indeed settled by Greek immigrants coming across the Ionian Sea. Overpopulation and famine on the Greek mainland and the 4Aegean Islands meant that by the eighth century BCE successive waves of Greeks, sailing westwards on the prevailing currents, began colonising both Sicily and the southern coastline of peninsular Italy. These Greek newcomers found fertile lands abundant in water and rich in grain and wine, together with a healthy climate. The area where they settled in Sicily and southern Italy became known as Magna Graecia (Greater Greece). Their cities included Neapolis (New City), or present-day Naples, and Tarentum (Taranto), founded by a group of Spartans. According to one tradition that began with Dionysius of Halicarnassus, a Greek-born contemporary of Virgil, the name ‘Italy’ actually derived from these Greek immigrants, specifically from a wise and just leader, King Italus, who ruled in the region of present-day Calabria. Italy therefore originally referred, by this account, not to an indigenous population but rather to Greek colonists occupying the peninsula’s southern shores.

King Italus may never have existed, but the Greeks certainly made a deep and lasting impression during their 500 or so years of political and cultural domination in the South. They introduced, among other things, the alphabet, and their vibrant intellectual and artistic life produced the brilliant scientist Archimedes and philosophers such as Empedocles and Pythagoras. The latter immigrated to Croton from the Aegean island of Samos in about 529 BCE, founding a religious community dedicated to moral and political renewal. The civilisation of Magna Graecia also left behind splendid monuments. The magnificent amphitheatre in Syracuse – where the playwright Aeschylus staged one of his tragedies in the 450s BCE – remains largely intact. Greek temples at Paestum on the Italian mainland and in the Valley of Temples at Agrigento in Sicily likewise survive, counting among the first of Italy’s many architectural treasures.5

In the eighth century BCE, these Greek colonists were only the most recent migrants to Italy. During the late Bronze Age, roughly 1150–950 BCE, the peninsula’s length and breadth became home to a mosaic of ethnic groups. Most were descendants of settlers who came across the Alps during the centuries-long Indo-European migrations, the massive and prolonged influx into Europe from the area north of the Black and Caspian seas (present-day Ukraine and southern Russia). Celtic tribes came to occupy large areas in the north between the Po river and the Alps. A patchwork of interlinked people, who for the most part spoke languages of Indo-European origins, pushed further down the peninsula, into parts of central and southern Italy. One of these languages was Oscan, named after the Osci, the ancient inhabitants of the region to the south of what would become Rome. Speakers included tribes such as the Sabines and one of their offshoots, the Samnites.

6More mysterious in origin was the civilisation to the north of the Oscan tribes: the Etruscans. They occupied ancient Etruria, the beautiful and fertile lands in central Italy that by and large encompass present-day Tuscany. They were unique insofar as they were linguistically different from the other Bronze Age arrivals on the Italian peninsula since, unlike Oscan, Etruscan was not an Indo-European-based language. All of which raises the question of where and when the Etruscans came from, if not this great migration. Their origins have been a matter of much conjecture and debate, from ancient times to the present, though a recent study of DNA has suggested that the Etruscans did, in fact, migrate from the same Pontic–Caspian steppe as the other Indo-European tribes.4

The Etruscans were one of the most dominant political and cultural forces on the Italian peninsula from about 800 to 500 BCE, overlapping with the heyday of the great civilisation of Magna Graecia in the South. The Etruscans were skilled artisans, metalworkers, seafarers and charioteers, a status-conscious people devoted to pleasure and luxury. However, by around 400 BCE, they as well as the Greeks and the Celtic tribes faced competition from a relatively new and increasingly irresistible power on the peninsula.

Sometime during the tenth century BCE or earlier, another tribe known as the Latini (whose name means ‘people of the 7plains’) came to occupy a region stretching some 80 kilometres south from the lower reaches of the Tiber to present-day Terracina. By the time we reach the eighth century BCE, according to legend, a chunk of this land was ruled by a king named Numitor, whose capital was Alba Longa (the exact site of which is much debated). Fraternal strife – what will become a pervasive theme in Roman history – enters the story when Numitor is usurped by his younger brother Amulius. Although Amulius takes the precaution of forcing Numitor’s daughter Rhea Silvia to become a Vestal Virgin (one of the six priestesses tending the fire in the Temple of Vesta), she soon gives birth to twins. The father, she claims, is none other than Mars, the god of war. Amulius orders the two babies to be drowned in the Tiber, but the men forced to carry out the deed are less than conscientious, merely placing the basket containing the boys into a sluggish stretch of water, which, as it ebbs, leaves them high and dry.

At this point the famous she-wolf appears and, hearing their cries and displaying her maternal instincts, begins suckling them. As these sons of Mars grow to manhood they prove themselves courageous and strong, ultimately killing Amulius and restoring their grandfather to his rightful place. Leaving Alba Longa in the capable hands of their grandfather, the stout young twins set off to found a new city that will rise along the Tiber near the spot where the she-wolf discovered them.

More fraternal strife. Romulus selects a spot on the Palatine Hill and begins marking the perimeter with a plough pulled by an ox. Remus decides on a different location a short distance to the southwest, on the Aventine Hill. To settle the matter, the twins resort to auguries, a borrowing from the Etruscans that involves interpreting the will of the gods through various signs in nature such as the behaviour of birds. Remus receives his 8sign first: six birds flapping their way over the Aventine. But then Romulus, on the Palatine, spots a dozen vultures. Which is more favourable: the sign given first or the one with more birds? The will of the gods seems open to dispute. A violent altercation follows in which Romulus kills Remus. Following this deadly skirmish, Romulus finds himself the sole leader of the new city, which, referencing his name, is called Rome. The date, according to the legend, is 21 April 753 BCE.

The she-wolf comes to the rescue of Romulus and Remus.

A new city needs people. Once he had built his walls and other defenses, Romulus set about finding inhabitants. He did so by opening the gates to all comers and, in a short space of time, attracted a ragtag band of runaway slaves and fugitives from justice. Because most of these new residents were male, Romulus needed to find women for them; but because they were such a rough lot, the people in the surrounding area were reluctant to offer their daughters. He therefore hit upon a desperate 9and brutal strategy – a mass kidnapping. Promising games and other entertainments, he extended an invitation to a nearby tribe, the Sabines, and when the festivities were underway his men drew their swords and began carting off the young women (a scene of half-clad writhing female panic later much beloved of painters such as Nicolas Poussin).

Poussin’s TheAbduction of the Sabine Women(c. 1633). Romulus surveys the scene from the upper left.

Such, then, were the legendary origins of Rome: a brawl ending in fratricide, a population of bandits, slaves and renegades, and a mass kidnapping to supply these outcasts with womenfolk and the city with babies. And yet this community of misfits, asylum-seekers and captives would become the stock for the greatest power the ancient world had ever seen.

*

10Romulus was the first of the seven legendary kings of Rome who ruled between 753 and 509 BCE. The last, Lucius Tarquinius Superbus, or Tarquin the Proud, embellished Rome with grand building projects and expanded its territory through an aggressive foreign policy. However, his kingship ended, according to legend, after his son, Sextus Tarquinius, raped a married woman named Lucretia, who then killed herself (a scene likewise much visited by painters). Her death was avenged by her husband’s friend Lucius Junius, who had earned the cognomen Brutus, or ‘stupid’, because he feigned idiocy to survive Tarquin’s tyrannical rule. Brutus put her corpse on public display and then called on the people of Rome to avenge her death and expel the tyrants. Tarquin was duly toppled and the monarchy abolished. For the next 482 years, Rome would be a republic, with the powers of the kings eventually (by the fourth century BCE) devolving onto, and shared by, a pair of annually elected consuls who could command the army and summon a 300-strong advisory body named the Senate. The name of this institution, which would survive for the better part of a millennium, derived from senex, ‘old man’, because it was staffed, in theory at least, by wise, grey heads. Ultimately the Roman Republic would evolve a system (later widely copied) whereby its government was separated into three branches: the executive (the two consuls), the legislature (the Senate and other assemblies), and the judiciary (the judges and priests).

Most offices, such as that of consul, were elected positions. Our word ‘candidate’ comes from the fact that someone vying for votes would appear in public in a whitened robe, the toga candidata(from the Latin candidus, ‘white’ – the root of words like incandescent and candle). A political campaign was known as an ambitio, from which, naturally, we get ‘ambitious’. The word 11ambitiocomes from ambire, ‘to go around’, because the white-clad candidates, like today’s politicians, engaged in glad-handing walkabouts, often accompanied by a slave whose job it was to remember the names of important voters. Candidates wrote their names in red on the walls of buildings, often proclaiming themselves a virumbonum – ‘a good chap’. Excavations at Pompeii have shown the fate a would-be politician named Quinctius wished upon his opponents: ‘Anyone who votes against him should go and sit next to a donkey!’5

The institutions of the Roman Republic would soon need to be robust enough to govern large numbers of people spread across wide areas. The Italian peninsula in 509 BCE was still a patchwork of different civilisations: the Celts and Etruscans to the north of Rome, the Samnites and other tribes in the mountains to the south and east, and the Greeks in their settlements hugging the coast to the south. The Roman Republic frequently came into conflict with these various neighbours. Disaster struck around 390 BCE when the city was sacked by a migrating tribe of Celts, necessitating the building of a defensive fortification, the Servian Wall (a stretch of which can still be seen outside Rome’s Termini station). Seventy years later, a defeat at the hands of the Samnites witnessed vanquished Roman soldiers forced to march under yokes (subiugum), a ceremony from which we get ‘subjugate’. However, by the middle of the third century BCE, through a series of conquests and alliances, virtually the entire peninsula, including Magna Graecia, would be incorporated into the Roman federation. The peninsula would therefore gradually transform from a land of Greek, Etruscan and Celtic cities and scattered settlements populated by tribes speaking a variety of dialects, practising different customs and forging varying alliances, into more of a political, cultural and linguistic unity.12

One of the great secrets of the success of Roman expansion was how they treated their defeated enemies. Their erstwhile combatants became what were called socii, from socius (partner), the root of the word ‘society’. The Romans developed a system of alliances with these partners – cities and ethnic communities up and down the peninsula – such that a kind of federation of tribes and city-states existed, with Rome at its head. The main obligation of the socii was to provide manpower to Rome in times of warfare, a kind of military conscription for which they received, in turn, protection from Rome and also a share of plunder. All were invested, to one extent or another, in the fortunes of Rome.

*

Rome’s dominance soon spread far beyond the Italian peninsula. The years between the middle of the third century and 168 BCE witnessed the Romans fighting the Carthaginians and then the Macedonian kingdoms that had succeeded Alexander the Great, who died in 323 BCE. Their victories in these prolonged and bloody struggles meant that by 168 BCE they had effectively become masters of much of the known world.

The first of the great civilisations to fall to unrelenting Roman pressure was the Carthaginians. Carthage was a colony founded on the north coast of Africa (in present-day Tunisia) in 814 BCE by Phoenicians from Tyre. Quickly becoming one of the wealthiest and most powerful colonies on the Mediterranean, Carthage controlled sea routes to the west and extended its influence along the top of the African continent (across present-day Libya and Morocco) as well as into Sicily, Sardinia and southern Spain. The Carthaginians maintained good relations with the Romans until the latter’s domination of Magna Graecia in the middle of 13the third century BCE. Between 264 and 146 BCE the Romans fought three ‘Punic Wars’ against the Carthaginians. (The name comes from the fact that the Romans called Carthaginians the Poeni, from the Greek word for ‘Phoenician’.) The most famous was the Second Punic War during which, beginning in the spring of 218, the great Carthaginian general Hannibal began a 1,500-kilometre march that would take him from southern Spain, through the Pyrenees, and then, via the Alps, into Italy, complete with a battalion of thirty-seven war elephants.

The journey from southern Spain to the Po Valley took five months and came at a cost of many thousands of Hannibal’s men: the ancient historian Titus Livius put the toll as high as 36,000. Hannibal also lost almost all of the elephants, primarily due to starvation. The feat is all the more stupefying considering how Hannibal’s exhausted and depleted army proceeded to inflict a series of defeats on the Romans that served as preludes to his most famous triumph, at Cannae in Apulia in August 216, fought against a numerically superior Roman army. In a tactically brilliant manoeuvre, Hannibal encircled and then mercilessly slaughtered the Romans, whose losses were put by the historian Polybius at 70,000 – still perhaps the highest casualties in a single day’s fighting that any Western army has ever suffered. Such was Roman panic and desperation that the most extraordinary measures were taken to appease the angry gods: two couples, one Greek and the other Celtic, were buried alive in the city’s cattle market. It was one of the few occasions on which the Romans practised human sacrifice.

Yet Rome did not fall. One refrain of Roman history is a devastating and humiliating disaster – such as those against the Gauls and Samnites – followed by an almost miraculous comeback. After Cannae, Hannibal appeared poised to march on Rome, only 400 14kilometres away. Posing as the liberator of the Italian peoples from their Roman oppressors, he knew his chances for success depended on the defection of Rome’s allies on the peninsula – the sociiwho formed the federation of independent states. However, most of the tribes on which Hannibal pinned his hopes stayed loyal to Rome, resulting in him and his army being confined to the south of Italy for more than a decade. In 203 BCE, with the Romans under Publius Cornelius Scipio taking the fight into Africa, Hannibal was recalled to Carthage. There, a year later, at the Battle of Zama, he suffered a comprehensive defeat at the hands of Scipio, subsequently known because of his famous victory as Scipio Africanus.

Decades later, Rome’s final confrontation with the Carthaginians, known as the Third Punic War, concluded with the destruction of Carthage in 146 BCE. That same year, the Romans also sacked and devastated another great and ancient city. In 214 BCE they had begun a series of wars against the Macedonians following their support of Hannibal in the Second Punic War. The subjugation of Greece was accomplished in a matter of a few decades as the Macedonian phalanxes, so invincible under Alexander the Great, proved no match for the Roman legions, the manoeuvrability of whose tactical units, the maniples, had been perfected during the long wars against the Samnites. Having defeated the Macedonians, by the middle of the second century BCE the Romans were battling their own former allies in the Achaean League, a confederation of Greek city-states in the central and northern Peloponnese. In 146 BCE, the Romans defeated the League in battle before the walls of Corinth, Greece’s wealthiest city. With the Senate having decreed that Corinth should be burned and all valuables taken as booty to Rome, the victorious army sacked the city in a horrifying display of savagery. Corinth would disappear from the map for more than a century.

Notes

1. Virgil, Aeneid, trans. Frederick Ahl (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007), ll. 171–2.

2.Aeneid, l. 282.

3. Dante, Inferno, canto XXXIII, l. 80; Petrarch, Canzoniere, CXLVI, ll. 13–14; Dionysius of Halicarnassus, Roman Antiquities, Book 1, XXXVII.

4. Cosimo Posth et al., ‘The Origin and Legacy of the Etruscans through a 2000-year Archeogenomic Time Transect’, Science Advances, vol. 7, issue 39 (September 2021).

5. On political graffiti and other electoral issues, see Matthew Dillon and Lynda Garland, Ancient Rome: From the Early Republic to the Assassination of Julius Caesar (Abingdon: Routledge, 2005), pp. 78–80.

2

‘Let the Die Be Cast’: The Crisis of the Roman Republic

the victories over the carthaginians and the Greeks gave the Roman Republic a worldwide empire. However, within decades the Republic entered a crisis that would endure for much of the following century and ultimately lead to its destruction.

One of the major challenges facing Rome was its system of landownership. Hannibal’s presence in Italy between 218 and 203 BCE – a time of continuous raiding and fighting – led not only to the destruction of 400 cities (as Hannibal boasted) but also to the devastation of the rural landscape: both sides burned crops, slaughtered livestock, destroyed farms and massacred local populations. These terrible conditions forced many small subsistence farmers from their land, especially in the South, where Hannibal’s troops were based. Their places were taken by much larger and wealthier landowners who, gobbling up huge portions of public land, defied the rule of a maximum of 500 jugera (125 hectares) of arable land per person.* In the 130s BCE a land reform was attempted by the politician 16Tiberius Gracchus, a grandson of Scipio Africanus. He advocated enforcing the 500-jugera law and redistributing their usurped territories more widely and evenly among the poor and landless. His plans proved unpopular with the large landowners and many senators (two groups with a considerable overlap). His efforts at reform ended abruptly in 133 BCE, when he was clubbed to death with a chair leg in the Senate and his body tossed into the Tiber. It was Rome’s first act of political violence for many centuries and a dark prelude of much that was soon to come.

The Republic faced an even more dangerous problem with, as in the old days, warfare between Rome and its neighbours. As we have seen, the Republic pursued a successful policy of military alliances, which meant the disparate tribes, cities and political communities inhabiting the peninsula were united under its rule. This unity was sorely tested on occasions such as Hannibal’s invasion, but the greatest challenge came with the Social War (that is, war of the socii) at the beginning of the first century BCE. The war ended with, for all intents and purposes, the unification of Italy on a cultural and linguistic as well as a political level.

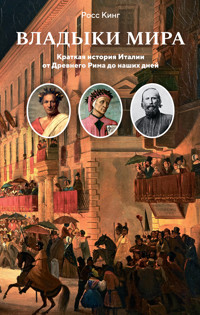

The Social War featured a coalition of the socii rising against Rome. It was prompted in part by the demand of some of them for Roman citizenship – for the rights and privileges jealously denied to them by the Romans, who referred to their allies dismissively as peregrini(foreigners). Citizenship had become a significant issue since the days of Tiberius Gracchus because only Roman citizens, and not the socii, were eligible to receive land as part of the planned reforms. The rebellion began in 91 BCE with the Marsi, an Oscan-speaking people whose most important city, Marruvium, was 110 kilometres east of Rome. 17They were quickly joined by other tribes, such as the Piceni, the Vestini, the Marrucini and the Samnites. The war is sometimes known as the Italic War because the allies, looking for a unifying identity against Rome, began using the term Italiato describe their lands. And here we find, besides the mythical King Italus, a different and more probable origin for the name Italy: either the ancient Oscan word for a calf (víteliú, coming from the Sanskrit vatsá)or the Greek word for an ox (ἰταλοί). ‘For in Italy,’ a Roman writer later observed by way of explanation, ‘there was a great abundance of cattle, and in that land pastures are numerous and grazing is a frequent employment.’1 More to the point, birds and animals, including bulls, oxen and calves, served as totems for the Oscan-speaking peoples. Whatever the case, in 90 BCE, the rebels gave to an otherwise undistinguished town 160 kilometres east of Rome, Corfinium, a resounding new name: Italia. They made it their seat of government and planned for it to serve as their capital once Rome was defeated. They struck a coin showing the Oscan bull goring the Roman wolf.

A coin issued in Corfinium showing a personification of ‘Italia’ crowned in laurels, as well as the bull goring the Roman wolf.

The Social War took a deadly toll on both sides. A historian named Velleius Paterculus, whose great-grandfather fought on 18the side of the Italian federation, estimated the total deaths, over the war’s two years, at 300,000. That must have been an exaggeration, but after a bloody stalemate the Romans agreed to the allies’ demand for citizenship. Henceforth everyone on the peninsula south of the Po would hold Roman citizenship, united as a political community sharing the same rights and privileges as well as, increasingly, the same language: Latin would soon become widespread, with the various Oscan dialects dying out in the decades that followed. The only other language that would endure this Latin domination, especially in the cities of the former Magna Graecia and among the educated Romans, was Greek.

‘Italia’ had been defeated, but a new and different Italia was born from this bloodshed. Only a few decades after the Social War, the orator and statesman Cicero delivered a speech in which he declared that the glory of Rome and the renown of its people were due to their recognition – based on the example of Romulus and the Sabines – that ‘this State ought to be enlarged by the admission even of enemies as citizens’.2 Rome’s traditional enemies, such as the Samnites, had themselves become Roman citizens. And yet unity on the peninsula, and indeed within Rome itself, was still fragile and fluctuating. The decades that followed the Social War were blighted by violent power struggles between military strongmen who finally pushed the Roman Republic over the brink of extinction.

These strongmen were enabled by reforms carried out in the Roman army during the last decade of the second century BCE by the general and statesman Gaius Marius. Rome’s war machine had formerly been staffed by an army of citizens raised by levies (the word ‘legion’ – the name for the bodies of infantry comprising some 4,500 men – comes from legio, ‘levying’). But since the 19soldiers needed to pay for their own food and weapons, receiving in return only a small stipend, the poor and propertyless were excluded from service. Rome’s acquisition of overseas territories in Spain, Africa and Greece required long campaigns and a permanent military presence – an impossible task for the conscripts in a citizen army who needed to return to their homes, farms and businesses. Marius therefore introduced reforms by which military service was opened to the poor, who would receive not only war booty but also, at the end of their service, grants of land. These rewards (which made war and conquest inherently necessary) became the responsibility not of the state but of their general, to whom the legions swore an oath of loyalty. And so rose what were more professional but essentially private armies: bodies of thousands of fighting men who owed their allegiance not to the Roman state but to their military commander.

Gaius Marius was to experience the implications of his reforms first hand. The first great clash, in the early 80s BCE, was between him and his one-time deputy, Lucius Cornelius Sulla. The casusbelli was who got to lead the campaign against Mithradates VI of the Hellenistic kingdom of Pontus, a vast territory that encompassed most of modern Turkey and encircled the Black Sea. Sulla ultimately prevailed over Marius thanks to extraordinary ferocity in a civil war that left thousands dead. In 81 BCE he declared himself ‘dictator’ (an ancient but little-used title) with sweeping powers that made him the sole ruler of the Roman world. It was a tremendously powerful position from which, perhaps surprisingly, he stepped down after two years, returning sovereignty to the Senate and people.

Yet internal peace and stability still eluded the Roman Republic as another power struggle developed. One of the parties was a former ally of Sulla named Gnaeus Pompeius, or Pompey. 20Few men have ever had a more adamant sense of their own grandeur. An admirer of Alexander the Great, Pompey had added Magnus, ‘the Great’, to his name when he was only twenty-five – an indication of his huge aspirations and self-regard. Cruel military exploits in Sicily and Africa earned him another nickname: adulescentuluscarnifex (teenage butcher). He added to his savage lustre in 71 BCE by crucifying thousands of fugitives along Via Appia following the slave revolt led by the gladiator Spartacus. Pompey’s greatest triumph, however, came in the East, where he captured Jerusalem, made Syria a Roman province and founded thirty-nine cities, one of which, with typical lack of modesty, he christened Pompeiopolis.

Pompey’s success in Asia and his popularity with the people of Rome alarmed many of the senators, who baulked at his requests to have them ratify his settlements in the East and give his retiring veterans – as they had been promised – their plots of land. To achieve his ends, around 60 BCE (the exact date is debated) Pompey made an alliance with another ambitious commander and adroit political operator feared by the aristocrats in the Senate: Gaius Julius Caesar.

Born in 100 BCE into a distinguished but impoverished Roman family, Caesar was the nephew of Gaius Marius. He also believed himself to be descended from both Ancus Marcius, the fourth King of Rome, and no less a figure than Venus – which conferred on him, he claimed, the power of kings and the reverence due to gods. By the age of forty he was a rising political star whose energetic self-promotion spooked the senators. A third party was added to this coalition when Caesar, deploying his able diplomatic skills, reconciled Pompey with Marcus Licinius Crassus, a former rival whom Pompey had deeply offended by claiming credit for defeating Spartacus. The secret alliance 21became known (to us, though not to the ancients) as the First Triumvirate, a Gang of Three who combined the political acumen of Caesar, the military prestige of Pompey and the wealth of Crassus, by far the richest man in Rome.

The alliance eventually fell apart. Crassus was removed from the scene when in 55 BCE, dreaming of glorious military triumphs to match those of Pompey, he clattered eastward with seven legions, bent on attacking the Parthians, whose empire sprawled across present-day Iran and Iraq. Instead of finding the success he craved, he died in battle in Mesopotamia, after which the Parthians used his disembodied head onstage as a prop in a production of a play by Euripides. Caesar enjoyed greater success with his own military enterprise when he marched north of the Alps and spent much of the next decade fighting the Gallic Wars against the Celtic tribes. He brought vast territories, including modern-day northern France and Belgium, under Roman control, at the expense, according to ancient estimates, of perhaps a million dead. In repeating the success of Pompey in Asia, he developed kingly ambitions. Pompey soon grew jealous of Caesar’s triumphs since for the previous few years he had been in Rome conducting more modest bread-and-circuses affairs, such as arranging shipments of grain and combats between wild beasts.

Following his conquests in Gaul, Caesar was ordered by the Senate to return to Rome after (as all generals were required to do before entering Roman territory) surrendering his command and disbanding his troops. This disarmament was the time-honoured way of stopping generals and their armies from marching into Rome and seizing power. Caesar crossed the Alps with his battle-hardened legions, and sometime in early January 49 BCE performed one of the most famous and momentous 22border-crossings in history. It began inauspiciously as, setting off at dusk with mules taken from a local bakery, he got lost when his torches extinguished, and he found himself wandering aimlessly on dark paths until he managed to find a local guide. But as he reached the southern boundary of his command, marked by a river named (because of its ruddy waters) the Rubicon, he spoke the first of his famous phrases: ‘Let the die be cast.’ His 13th Legion, armed to the teeth, entered Roman territory. Such was the panic and confusion that Romans fled the city for the safety of the countryside, and people from the countryside fled their villages for the safety of Rome.

Pompey had assured the Senate that he would raise troops to battle Caesar, but when his legions failed to appear – most of his army was away in Spain – he, too, panicked and fled Rome, with most of the senators following hard on his heels. This latest head-to-head then witnessed Caesar pursuing Pompey, first across the Italian peninsula on Via Appia from Rome to Brundisium (Brindisi), then across the Ionian Sea to Greece – where Caesar trounced Pompey’s troops at Pharsalia – and finally into Egypt. Here Pompey’s magnificent career ended on a strand of beach at the behest of the fifteen-year-old pharaoh Ptolemy XIII, the brother of Cleopatra. He later presented Caesar with the gift of his rival’s severed head. Cleopatra, meanwhile, was smuggled into Caesar’s presence in a rolled-up mattress. She later gave birth to a child pointedly named Caesarion (‘Little Caesar’ in Greek).

With Pompey and Crassus gone, Caesar’s pretensions were unbounded. Back in Rome, he occupied a golden throne in the Senate and took to donning a purple toga (the costume worn by the Etruscan kings). He placed his head on coins and statues of himself in temples. In one famous and controversial 23episode, during a festival in the Forum, perched on a throne, he was offered a crown, which he made a hasty show of rejecting once the revellers showed a distinct lack of enthusiasm for this coronation. He did take to wearing a crown of laurel leaves, which allowed him to conceal his balding pate. Worst of all for his critics, early in 44 BCE he became dictatorperpetuo(dictator for life) – a position that looked little different from that of a monarch. The very name of the post made it highly dubious that he would ever relinquish his powers, as Sulla had done.

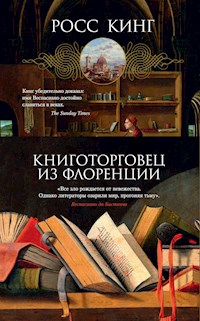

Jean-Léon Gérôme’s 1867 The Death of Caesar, showing Caesar sprawled at the foot of Pompey’s statue.

Caesar’s overweening ambitions and the drastic shift to one-man rule quickly became too much for many Romans to bear. A conspiracy against him, involving sixty senators, was hatched by the men Caesar called ‘those pale, thin ones’:3 Gaius Cassius Longinus and Marcus Junius Brutus, the latter supposedly a descendant of the Brutus who founded the Roman Republic. The attempt on his life came on one of the most famous dates in history, the Ides of March (15 March) in 44 BCE. On that day he went to the Senate, temporarily housed in Pompey’s magnificent 24theatre because the Senate building had burned down eight years earlier during a violent altercation between warring factions. Once inside, the assassins pounced, skewering him with twenty-three wounds. The only assailant against whom he made no show of defending himself was Brutus, who stabbed him in the groin. According to the historian Suetonius, he uttered not the Latin phrase (Et tu, Brute?) made famous by Shakespeare but, rather, ‘You too, my child?’, which he spoke in Greek (καὶ σύ, τέκνον).4 (Rumour had it that Brutus was Caesar’s illegitimate son.) Caesar then slumped against the blood-spattered pedestal of a statue of Pompey.

The motives of the conspirators and the justification for their actions have been debated for more than two millennia. Was his murder a foul crime or an idealistic and patriotic act performed by Brutus, ‘the noblest Roman of them all’? The ancient sources report a wide range of motives among the killers, not all of them especially high-minded. Many were inspired by grudges, believing, rightly or wrongly, that Caesar had impeded their careers. Brutus, too, may have been spurred into action for personal reasons: Caesar’s treatment of Brutus’s mother, Servilia, his long-time mistress. In any case, the varied and, in some cases, petty personal motives of the conspirators meant that with Caesar gone they possessed no unifying vision or principle, and no single-minded commitment to, or plan for, restoring the Roman Republic. It can be no surprise, then, that what followed was a dozen more years of chaos and violence.

Notes

1. Aulus Gellius, Attic Nights, vol. 2, books 6–13, trans. J.C. Rolfe, Loeb Classical Library 200 (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1927), p. 299. For the Sanskrit origin, see Carl Darling Buck, A Grammar of Oscan and Umbrian (Boston: Ginn & Co., 1904), p. 33.

2. Cicero, Pro Caelio. De Provinciis Consularibus. Pro Balbo, trans. R. Gardner, Loeb Classical Library 447 (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1958), p. 665

3. Plutarch, Lives, vol. 7, trans. Bernadotte Perrin, Loeb Classical Library 99 (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1919), p. 589.

4. Suetonius, Lives of the Caesars, vol. 1, trans. K.R. Bradley, Loeb Classical Library 31 (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1914), p. 141.

* A jugerum was the amount of land an ox could plough in a single day.