9,59 €

Mehr erfahren.

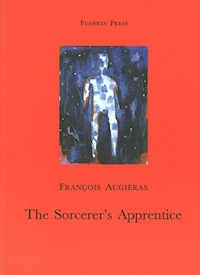

- Herausgeber: Pushkin Press

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

In the depths of the Sarladais, a land of ghosts, cool caves and woods, a teenage boy is sent to live with a thirty-five-year-old priest, but soon the man becomes more than just his teacher. Published in the United Kingdom for the first time. The Sorcerer's Apprentice is a gallant, almost magical book that is one of modern literature's esoteric, underground texts.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2013

Ähnliche

FRANÇOIS AUGIÉRAS

THE SORCERER’S APPRENTICE

Translated from the French by Sue Dyson

THE SORCERER’S APPRENTICE

Contents

Title Page

The Sorcerer’s Apprentice

Afterword

Also Available from Pushkin Press

About the Publisher

Copyright

The Sorcerer’s Apprentice

IN PÉRIGORD there lived a priest. His house stood high above a village made up of twenty dilapidated dwellings with grey stone roofs. These houses straggled up the side of the hill, to meet old, bramble-filled gardens, the church and the adjoining presbytery, which were built on rocks reflected in the River Vézère, flowing past at their base. Few people lived there; this priest served several parishes, which meant that, since he spent all day travelling round the countryside, he did not return home until evening. He was aged around thirty-five, just about as unpleasant as a priest can be, and although this was all my parents knew about him, they had entrusted me to his care, urging him to deal strictly with me. Which indeed he did, as you will see.

On the evening of my arrival, the sky was a soft shade of gold. He did not offer me any supper; the moment I turned up on his doorstep he took me straight to my room, which was located in a corridor as ugly as himself. Leaving the door ajar, he abandoned me without a word, if you discount a few unanswerable phrases, such as: every cloud has a silver lining; the tables are turned; come what may; sleep well in the arms of Morpheus; and other such drivel. I heard him go into the next bedroom, moving about, doing God knows what, talking to himself, then there was silence.

I had been asleep for less than an hour when I was awakened by a terrible howling. Sitting bolt upright in bed, my eyes wide open, I waited for what seemed an eternity, petrified that I would hear another sound as terrible as the first. But nothing else disturbed the silence of the night. The moon picked out a few leafy branches among the shadows in a wild garden behind the presbytery; its beautiful rays shone through the panes of my little window, lighting up the corner of a table covered with my blue school notebooks, and a whitewashed wall, and faintly outlining the rim of a water jug. I was sleepy; I drifted off again without worrying too much about my extravagant priest’s odd ways, for it was he who had shouted out in the next room, which was separated from mine only by a thin partition wall.

In the morning, when I went downstairs, I found my parish priest in an almost good mood, making coffee. I owe it to him to mention that at his house I drank the best coffee in the world, delicate yet strong, with a curious taste of embers and ash. He took a great deal of care preparing it according to his own method, all the time muttering away, not to me, but to the flames which he blew on gently, rekindling the embers, talking to them as if they were people. He removed the coffee from the heat as soon as it began to bubble, returning it for a brief instant to the burning coals which he picked up in his bare fingers, as though he derived enjoyment from the act, and without noticeably burning himself. The whole process took a good quarter of an hour, and he spent the entire time crouched in the hearth, with his cassock bunched up between his thighs.

After we had drunk our coffee, we went out into the garden. Sitting on some steps, at the intersection of two pathways, he got me to translate some Latin passage or other from my school books. As far as I could see, he had a rather poor grasp of Latin. He had the unpleasant habit of vigorously scratching his horrible black hair, and that got on my nerves. What’s more, he kept reminding me how grateful I should be to my parents, who had had the excellent idea of entrusting me to him. If my attention wandered, even for a moment, he seized me by the ear and I felt two hard, sharp fingernails sink into my flesh. He wore a disgustingly dirty cassock, for he was extremely mean with money, and thought he looked good in it. He addressed me by the sweetest names, while at the same time poking fun at me; he displayed the polite manner one might use when celebrating a small Mass; he kept calling me “Young Sir”; it was as if he were saying: I’m only a peasant, I owe you a little politeness; and there you have it, all in one go; try to be content with it, young Gentleman. This Latin lesson, punctuated with little courtesies, lasted no more than a page; he stood up; I did likewise, and both of us were delighted that it was over—in my case the Latin, in his, the politeness. To tell the truth, in that June of my sixteenth year, what I really wanted were language lessons of a different kind, for love is a language, even more ancient than Latin (and there are those who say even that defies decency).

Leaving me to Seneca and Caesar, he strode off into the countryside. He had charge of several parishes; very well then, let him leave me on my own, this solitude would not be without its attractions; I was perfectly capable of passing the time and getting by without my priest.

As soon as he had gone, I put down my books and gave up trying to follow Caesar’s conquests; instead, I opened my eyes wide and took a long look at my new life. All along the banks of the Vézère ran the vast, thickly-wooded hills of the Sarladais. Closer to me, our garden was broken up by little low walls made of heaped-up stones, and by steps and pathways. All kinds of plants were jumbled up together, growing wild, almost hiding the once-ordered layout of a rather fine formal garden. Everything flourished higgledy-piggledy, rose bushes and brambles, flowers, grass and fruit trees. This lost order reinforced the garden’s charm, as well as the anxiety which you felt as you tried to find your way round that tangled mess, whose traceries of flowers were bizarrely watched over by a pale blue plaster statue of the Virgin Mary. She rose above the wild jumble of plants, looking just a touch simple-minded, with her tear-filled eyes, her insignificant, veiled face like a blind woman’s, her gentle, soft hands and her belly tilting forward. Beyond her it was all emptiness; our garden, which was perched at the very summit of the rocks, tumbled down towards the azure sky, the waters of the Vézère and the village rooftops.

Our church shone in the sunshine. It was a former monastery chapel, with thick walls pierced by narrow windows like arrow-slits. But the thing which commanded my attention was the presbytery, which I had caught only a glimpse of the night before. It seemed very ancient, with its lintelled windows and its substantial stone roof. As I was alone, I decided to get to know it better.

On the ground floor was the kitchen, where we had drunk our coffee. The dominant feature was a vast fireplace, which filled the whole room with smoke. I pushed open a little door beside a cupboard, and was surprised to see that it led into a stable, occupied by a sparse flock of bleating sheep. I found log-piles and a kind of forge.