7,19 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Salt

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

The South Westerlies is an attempt to know place (Gower) through the creation of a collection of short stories. Place is not a cosmetic backdrop, but an affecting agent in the lives of a wide cast of fictional characters. The collection is unified by the tone of the prevalent dank south-westerly wind that blows across the peninsula, the UK's first designated area of outstanding natural beauty. However, the author chooses to let her gaze fall on the downsides of a much vaunted tourism destination and a place that is too beautiful, perhaps, for its own good.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

Ähnliche

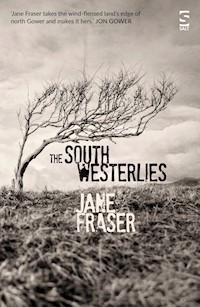

THE SOUTH WESTERLIES

by

JANE FRASER

SYNOPSIS

Jane Fraser’s dark and unsettling debut collection of short stories explores the windswept Gower Peninsula of South Wales: a place of folklore and myth, birth and death, envy and revenge.

PRAISE FOR THIS BOOK

‘Fraser’s stories are compellingly told and carefully crafted. She shares a heightened, acute sense of language with Annie Proulx and the right to comparison with such a prose stylist is properly won. And just as Proulx claims the lodgepole pines and wide-skied landscape of Wyoming as her own so too does Jane Fraser take the wind-flensed land’s edge of north Gower and make it hers. She has given this reader, at least, what he so often desires, namely the tang and sharpness of savouring language seemingly newly minted.’ —JON GOWER

‘The South Westerlies is obviously the work of a serious, committed and thoughtful writer, open to both inner and outer realms, the quivering sensitivities of the self, and the tactile, textured world outside, a kind of aesthetic elision between character and place.’ —ALAN BILTON

‘The South Westerlies illustrate a landscape depicted with great specificity and detail, interfusing an exploration of place with the lives and perceptions of the characters who inhabit it… The stories display a sure grasp of the short story form and the techniques and processes of prose fiction… The collection is an original and valuable contribution to the literature of Gower and Wales.’ —TRISTAN HUGHES

The South Westerlies

JANE FRASER lives, works and writes fiction in Gower in a house facing the sea. By day she is co-director of NB:Design along with her husband, Philip. In 2017 she was a finalist for the Manchester Fiction Prize. In 2018 she was placed second in the Fish Memoir Prize and selected as one of Hay Writers at Work. She has a PhD in Creative Writing from Swansea University.

To my husband, Philip, for his encouragement and unfaltering belief in me, my three granddaughters, Megan, Florence, and Alice, for the joy they bring every passing day, and to the memory of the late Welsh poet, psychogeographer, academic, and man of Gower, Nigel Jenkins.

This is the Boat that Dad Built

Raymond Williams thebutcher rises every day at 6 o’clock sharp. Above the shop he swings his legs over the edge of the bed onto the threadbare carpet as soundlessly as he can. He doesn’t want to wake Mum, still sleeping deeply now as morning comes; she needs her rest. He pads in his slippers past the bedroom of us, his two children, Jane and Peter, and descends the steep stairs with a young man’s tread, the wedding ring on his fourth finger tapping against the varnished banister. He’ll bring us a cup of tea and a biscuit in an hour or so; no need to disturb us yet, let us come-to gently, drift easily into the day. Till then he’ll chop: the rhythmic plodding thud of his life, marking time, Monday to Saturday, cutting grooves into the already worn surface of the wooden block that bows in the centre with the weight of the heavy years.

Dad made his vows ten years earlier on a Monday morning in June soon after the Coronation. And he meant them. Till death us do part; forsaking all others as long as ye both shall live. He doesn’t want a lot out of life; he’s easily pleased, content with his lot. Then again, perhaps that’s the problem. Not that Mum acknowledges there’s a problem. It’s just her nerves, she says – can’t seem to sleep at night, feels constantly low. She often talks of things past, of the good clothes she used to have when she was growing up, from fashionable department stores like Ben Evans or Sydney Heath’s in the Swansea town centre. And she talks endlessly about Martin who’s a dentist now in middle-class shore-line Mumbles. She could have had this; she could have had that. But she chose Dad, the red-headed man she spied on the beach at Langland soon after the sands were free again at the end of the war.

But for now she goes for a lie down every afternoon as life continues to play out in the terraced streets around her. The flimsy peach curtains are drawn in the dim bedroom, the eiderdown pulled up tightly to her chin, her breathing as rhythmic as the chopping below. Her silent dreams are taking her where Dad can only guess, away from the hollow depression she’ll leave in the feather mattress when she gets up.

“Where’s Mum?” I demand as soon as I get in from school and pass through the shop where my father stands, still chopping at his block.

“In bed. Having a little lie down,” he replies.

“It’s not fair. Why is she always in bed?”

Dad says nothing as he chops on. Our eyes meet for a second in my reflection in the mirror behind the block as I pass by. I disappear into the back of the house which lies achingly empty at the end of the afternoon.

Much later, when Mum finally leaves the shuttered fug of the bedroom and comes downstairs, it’s obvious she senses my feeling of resentment and abandonment. She is gagging on her guilt but fends off the uneasiness bittering her mouth by going on the attack. She tells me that I am a moaner, that I was born moaning probably because I was a forceps delivery. Wednesday’s child is full of woe, she tells me, which doesn’t seem fair either.

Dad never takes my side. His blind patience infuriates me.

“Look Jane, don’t go upsetting your mother now – saying nothing’s best. You know she needs her rest and likes a little lie down in the afternoons. She’s a bit down at the minute.”

I don’t know why she needs her rest. I just know it’s different; this strange house where my mother is neither present nor absent, hidden behind the façade of the shop window where the sheets of greaseproof paper hang on steel hooks at the end of each day and close us off from the pavement and the rest of the world.

But Mum, at times, seems on Dad’s side, as though she has admiration for his certain type of skills.

“He’s good with his hands,” she tells us from on high, “very practical, methodical. Of course, he didn’t have much of an education – wasn’t allowed to – had to come out of Dynevor Grammar School at fourteen and help out in the shop because of the war and all that. So he’s not a great reader, more a non-fiction man.”

Yes, that’s true; the only point of reading as far as he is concerned is for facts. So it’s Amateur Photography or Woodwork Today. He’s not a fiction lover like Mum, though he loves to sing and soar away on Welsh hymns. But it is around this time that he stops singing in the Morriston Orpheus Choir because Mum is becoming tired of him going to choir practice twice a week. She says it’s just the fact that she’s left alone in the evenings with nothing to occupy her but the children. He doesn’t want to upset her even more so he accommodates. Yes, that’s the word for Dad; accommodating. And so when the music leaves his soul he embarks on a once-a-week woodwork course, on a Monday evening.

“It’s not fair, Dad,” I say. “Why do you always give in to Mum, always let her have her own way? You love your singing – you should tell her!”

“Look Jane, your mother hasn’t had an easy life, what with one thing and the other – there’s no point making things worse – it’s just not worth it, it’s not that important. And anyway, I’ve been fancying turning my hand to a bit of woodwork for a while now.”

There’s a look of obedient dog about him; a dog that keeps running after thin twigs and sticks chucked by his mistress on a cold, deserted beach – a dog that keeps running back, crouching, begging for more until he’s panting and his legs won’t carry him anymore. A dog who doesn’t want to give up or cause displeasure.

But the woodwork times are solid times – hardwood in our family. He works in jarrah and karri and fruitwood and mahogany. He brings the exotic to the back of the shop. He planes and joints and bevels and turns grained planks into an array of wonderful creations which adorn the place: delicate light-pulls for the bathroom, fine-turned lamp bases for the living room, a teak desk with a knee hole for me to do my homework, a garage with petrol pumps and even ramps and a sign painted red, Pete’s Motors, for my brother. And for Mum, a lustrous, mahogany bedside cabinet which feels like satin, but is solid and heavy, made to last. It glows warm red with a brass-encrusted handle that glitters like gold and a drawer that glides with a whisper because of his perfect dove-tailing.

It’s then he decides he’ll build the boat. The boat that will spirit us all away from the terraces of Swansea east. And in the short precious times that are available to us on Saturday afternoons and Sundays, he will be Neptune, King of all he surveys, at the helm. With his family all together on board they will skim the safe waters, not too far from shore, but all at sea. He smells the dream.

And the dream takes shape in the unused bedroom above the shop at the front of the house. His crew is already all on board. Meticulously, he works from a plan: build your own 11-foot dinghy. The step-by-step guide lies open on the wooden floorboards and he’s dressed in his brown button-through cotton overall that replaces his butcher’s apron, when the steam of the Morphy Richards electric kettle eases the carefully sawn strips of wood into shape, and they bring flesh to the bones as he moulds them carefully around the ribs of the skeleton of the framework.

The dream starts to become visible.

“It’s coming, Ray, taking shape,” Mum purrs, as though she wants to be on board for the first time in her life.

“You’re so clever Dad . . . how long till it’s finished?” we kids say together.

And we are allowed to mix the glue that is thick and strong, the heady-smelling adhesive that will hold the wood in place, make it safe and watertight before we brush on the undercoat and the final varnish on the prow.

“She’s a beauty,” says Mum. “I’m really looking forward to summer.”

And for the first time in his life Dad must feel something akin to pride, coursing through his industrious veins. And as the long winter nights start to shorten and spring wafts in through the open sash window, turps and thinners and plywood and paint and brushes and balsa and varnish and vanity and excitement and expectation choke the air. The boat is complete.

Mum brings tea in the four best blue-and-white-striped china mugs on a tray for the ceremony. We all eat Marie biscuits in the early ethereal evening light. It is then, with great seriousness and dignity, that Dad, in his best BBC English, christens his dream:

“I name this boat, JAPET. May God bless her and all who sail in her.”

And he means it, really means it. Dad who is so earnest, who has such hope and optimism. Logically, as expected, in his matter-of-fact sort of way, he takes two syllables and melds them together with love. He takes his children’s names and marries them in a flourish of gold seraph-face lettering and fixes them securely with brass screws to the prow of his boat. His whole world is reflected.

It is side-splitting when the great crafter of dreams realises that his creation is too big to leave the room by normal means. The dream has outgrown the physical context; it is more of a liner than a dinghy. It is confined to quarters for a while as he works out how to resolve the situation. Another small trial sent to test him. All part of life’s rich plan, he thinks.

But soon after, a sense of sadness, perhaps even shame, sweeps over me as I see my father’s visions all dangling in chains above the pavement where Evan the Milk’s ageing milk float will soon receive it, in the back space where the milk crates have been cleared. The window frame is taken out and it’s just there, JAPET, swinging like a dead man on a gibbet. I feel my face redden with embarrassment or perhaps a sense of things to come. I am too young to understand fully; but some feeling sends my emotions into overdrive.

“Stop being so over-dramatic, Jane. See the funny side,” says my mother. That’s not fair, I think, coming from her.

This is the time when fairness is something solid, tangible. Something you can feel in your hands like the white Avery scales on the counter in the shop below. The time when everything equates; balances up. When good things happen to good people, when good people don’t die young, when hard work results in rich rewards – when the more you give, the more you receive, the more you love, the more you are loved. You know the sort of time. The time I see my father’s boat, my father’s pride, being mocked by things as yet unseen, undefined.

We don’t have a trailer to ferry the boat back and fore to the beach – can’t afford one – so JAPET is housed permanently at Oxwich Bay. Dad comes to an arrangement with a local land owner, a Sir Charles Stuart something-or-other, who has an estate where the woods nestle up to the Old Rectory and run right down to the shore line tucked away at the eastern corner of the bay next to the church at St Illtyd’s.

“She’ll be safe as houses there,” he says confidently. “Even have God looking out for her!”

It is probably then that I, like my mother, see the ordinariness of our little dinghy which has been until then, wondrous. It is not lustrous and fibre-glassed, replete with visors and padded leather seats like the others that flaunt themselves in the bay. Vulgar, Mum says they are, new-moneyed, tersely, her full lips suddenly drawing in, thinning. I sense it is the kind the dentist I have heard about would probably have now. Our JAPET is a mere eleven foot. It doesn’t have a Mercury 200HP outboard engine that cuts through the water nor does it bounce at speed leaving a great wake of white water behind. JAPET has a 2-stroke engine which leaves a rainbow of smelly oil behind as it chugs diligently across the bay, out from the corner of the beach that loses the sun in the afternoon, out into the open sea towards the steep limestone cliffs, glinting in the beckoning sunlight at Tor Bay.

It is another world, out there away from the shore. We are free, unfettered on the calm and open sea. We sing in unison, ‘Life on the Ocean Wave’ or ‘We All Live in a Yellow Submarine’ over and over again because our new life jackets are yellow; fluorescent-yellow life jackets that lace up at the front and have sharp edges but will keep us buoyant and free from danger. And when the engine is cut and we jump overboard, we bob like light cork in the fish-filled water. And Mum’s bather is yellow too; two-toned, an acid yellow and a darker hue, more mellow, smudging together in circles like the sun and a halter neck, a boned bodice and a skirt like a tutu that skims the top of her thighs. And with her rimless sunglasses with the golden metallic wings she is a starlet from a Hollywood film set. Though the films are in black and white, she is a technicolour dream.

These are sunshine times, and Dad beams for the dream he has made possible. And I can see him imagining Mum, his starlet, on a mono-ski behind his powerful boat. He has the wheel in one hand and is looking back over his shoulder, the spray salting his face. And she is smiling, her amber eyes sparkling; so confident she is raising her one arm and waving as she carves up the ocean. We kids are screaming with joy on the pretend padded leather seats as the boat smacks and slaps on the surface. We bounce up and down as he steers us at speed fearlessly across the bay. In the distance, at the far end of the wide sweep of limestone coastline, the afternoon sunshine looks even brighter, its warmth drawing us towards it. But perhaps he thinks we are sailing a little too close to the sun and the dreams are starting to melt when the 2-stroke engine cuts out and there is a silence. We row back to shore then, our arms aching, back to the safe haven of the trees next to the church, our home-made oars, varnished with love, slicing and shining through the water, rhythmically keeping time to the gentle chant of the skipper.

Summer is passing. The first chill days of autumn are about to descend, the leaves to fall off the trees. Mum does not want to go out in the boat anymore.

“It’s getting a bit cold for me, Ray – you go with the kids. I’ll stay on the shore.”

And there she sits on the red and green striped beach towel on the cool damp sand at the water’s edge. She’s smiling and waving at us as JAPET, sounding now like a sewing machine, splutters into life and stutters across the bay, fading into the distance, bathed in that low glow of late September light.

Dad must sense Mum fading too. No more a Hollywood starlet, her screen days are over and she’s feeling the chill again, already wrapped tightly in Dad’s worn tweed sports jacket and a headscarf and sipping tea from a red Thermos flask, alone on the shore.

It is the time when the season comes to an end with a sudden storm. A rise of the wind, an eerie omen that precedes the tempest; fork lightning, torrents of rain – a complete cataclysm. They say it is spectacular, the people in Oxwich who see it play out over the bay, the sea a deep plum-purple, unfathomable.

But of course, we aren’t there to witness it; we’re back in Swansea east. We get a call about a day later from the Old Rectory – we need to come down, it’s not good news. Sir Charles Stuart something-or-other hasn’t bothered to manage these woodlands at the estate’s edge for years. You can see that the trees are dry, desiccated, brittle. It’s no wonder they split. I know that God has done this on purpose.

They say nothing, Mum and Dad, as they lift the trunk off the smashed hull. The split is perfectly symmetrically, right down the middle. It must have been one mighty strike, a mighty smite. The engine is bent and buckled; useless. And all Dad’s love and labour is litter now, chips and chunks on the woodland floor. Dad bends and rummages around to retrieve the name, JAPET, still golden among the debris, and rubs it clean on the leg of his trousers. I feel his unshed tears well-up inside me festering in a fierce anger against something or someone; but he remains his calm self as he stands there with his two children at his side.

“Oh well, at least not everything’s lost,” he says.

And Mum says nothing, just stands apart, before walking off through the leafless trees.

There is a feel of the coming winter.

A Passing Front

Things were neverthe same after she’d left that late September day. I’d expected autumn storms to sweep in off the Atlantic, just as they always did: south-westerly squalls that would wipe summer clean away, once and for all. But that year, they didn’t come.

The Indian summer hung on like my wife’s long and lingering presence. Well into October, the garden groaned with an abundance of growth: yellow roses still bloomed, clinging to the old stone wall of the shed, filling the air with sweetness. Strawberries cropped a second time, overflowing from the warmth of the terracotta tubs and climbing beans and courgettes choked the raised beds. And from the gnarled, old apple tree that she loved, hung boughs, heavy with the weight of Nutmeg Pippins, begging to be picked. But I just didn’t have the inclination.

Of course, the days were shorter come November, and relatively cooler, but the sun insisted on shining still. Its rays slanted through the branches of the apple tree, creating a shimmering, dappled light. Leaves, usually long-gone, clung bravely to the twisted branches, along with the odd apple. I should have started tidying-up, I suppose, looking back: getting things in order, ready for the winter, but it didn’t feel as though winter would come that year. It’s not natural, this, my old dad kept muttering, as he came and tried to take control of the garden, even the grass is still growing. I felt helpless to help him, my father. There, there, he said softly, as if I were a child again, it’ll come, boy.

Under the balding canopy of the tree, the glut of unpicked apples lay on the grass. In the cool of dawn, and just before dusk descended, I would watch a lone magpie bobbing its ugly monochrome head in a monotonous rhythm, spearing its thieving, jet beak through the skin of the abandoned fruit and gouging its way into the exposed flesh, ripe beneath the surface. Deeper and deeper it would dig, until it would have its fill. And then it would just take flight.

The harvest of apples just lay rotting. Daily I’d tread along the slippery, moss-covered path that skirted that tree and notice that the fruit was shrinking, putrefying. The skin that hadn’t been picked and gnawed by birds was brown and the fruit inside soft, pulpy. The heady waft of sweet-decay filled the air and attracted swarms of wasps that hovered, circling, inches above the rotten apple flesh. They seemed half asleep or drugged; high on this late bounty. They were strangely hypnotic circling this way, desperate to taste of the last fruits of summer.

But in December, the first frost came down. It bit hard. I’d been lulled into a false sense of security by the magic trickery of a summer I thought would never end. Overnight the garden was transformed; and I ventured out incredulous at how rapidly appearances could change. Under the fragile white frosting, all evidence of what had once been, had been covered up, hidden under this flimsy blanket. The world was stripped of colour; and I retreated indoors, to the warmth, away from the sudden shiver of winter.

The conservatory had been her idea so that even at that point in my life I had to acknowledge she’d been right. It took advantage of every ray of sun from its rise over the Bulwark behind the house, to its fall into the ocean out front. Winter’s blast might have made itself felt outside, but inside, in the conservatory, I was warmed through, snug and secure in my room of glass. Always light and hot, that even without central heating I’d have to open up the sash windows to let in some fresh air.

It must have been then that the first of the wasps found its way in; tempted by this easy warmth, away from the sudden and inhospitable chill outside. But once inside, it must have sensed that getting out would be more difficult. After a few minutes buzzing over the fruit bowl, it found itself trapped behind the glass. It was a frenzy of transparent vibrating wings, flying into the windows, disorientated and agitated, its tiny black and yellow thorax beating against the pane, its antennae feeling this barrier to escape, over and over again, as it pounded against the glass, perhaps sensing its own futility.