Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Arc Publications

- Kategorie: Poesie und Drama

- Sprache: Englisch

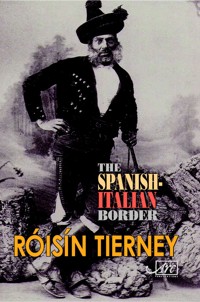

As the title suggests, this is a book that contorts the world we know, oddly fluid and yet grounded in subjects that range from rural Ireland to sub-maritime journeys to Spain, from unheard of languages to ghost dogs. Through acute observations and litanies, there are echoes of song and chants that pull you innocently through to often shocking climaxes. However, never lost underneath all these poems is a genuine celebration of life and its peculiarities. Róisín Tierney was born in Dublin in 1963 and studied Psychology and Philosophy at University College Dublin. She moved to London in 1985, where she worked in many areas, from theatrical make-up artist to museum administrator. After several years teaching in Spain (Valladolid and Granada), and Ireland (Dublin) she is now settled in London. Her poetry has appeared in anthologies from Donut Press, Ondt & Gracehoper and Unfold Press. This book is also available as a eBook. Buy it from Amazon here.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 48

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2014

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

THE

SPANISH-ITALIAN

BORDER

Published by Arc Publications

Nanholme Mill, Shaw Wood Road,

Todmorden OL14 6DA, UK

www.arcpublications.co.uk Copyright © Róisín Tierny 2014

Design by Tony Ward

Printed in Great Britain by TJ International, Padstow. 978 1908376 34 3 pbk

978 1908376 35 0 hbk

978 1908376 36 7 ebk Acknowledgements Acknowledgements are due to the editors of the following publications in which some of these poems first appeared: Poetry Ireland Review, The Sunday Tribune (New Irish Writers), Magma, Arabesque Review, Horizon Review, The London Magazine, Moonstone, The Wolf, The Virago Book of Christmas, Moosehead Anthology X: Future Welcome, In The Criminal’s Cabinet, (nthposition.com), The Lampeter Review, The Writers’ Hub and Poems for a Better Future (Oxfam).

Several of these poems have also been published in the following pamphlets and pamphlet anthologies: Gobby Deegan’s Riposte (Donut Press, 2004), Ask for It by Name (Unfold Press, 2008), The Art of Wiring (Ondt & Gracehoper, 2011) and Dream Endings (Rack Press, 2011). Cover: Photograph of Chorrojumo, by José García Ayola, © Museo Casa de los Tiros, Granada, Spain. This book is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to provision of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part of this book may take place without the written permission of Arc Publications.Editor for the UK and Ireland: John W. Clarke

THE

SPANISH-

ITALIAN

BORDER

Róisín Tierney

2014

for Christopher

Contents

IChosen

The Sacred and the Profane

Waters

The Blush

Swanky

Trajectory

Feet

The Only Hue

The Liminal

Invierno

Song

Gone

On Watching Ray Mears’ Extreme Survival Guide

Half-Mile Down

Hunt

Global

Crush

As is the Archaeopteryx

Oouf!

The Pact

Untitled

Museum Interview

Nebamun’s Servant Rebukes Him

Song of the Temple Maiden

Héloise Learns to Modify Her Desire

Lucid Interval

Dog-Days

Anna IIThe Spanish-Italian Border

Learning the Language

Mariposa de Noche

Recipe for the Sky

In an Empty Alcove in the Prado

El Rey de Jamón

The Panzemashorn

Gothic

La Vida Gitana

Cathy

Cult

Stink

London Hospital for Tropical Diseases, 2003

The Suicides

Diogenes Syndrome

Vera

Asylum

Lluvias

Musca Domestica

Death-Mask

Dream EndingsNotesBiographical Note

I

Chosen

The red bullock sways

as he mounts the gangplank

of the dung-splattered cattle truck.

He rolls his head from side to side

and blinks his feathered lashes.

His tongue floats up

towards his nostrils comfortingly,

as his sweet breath clouds the morning air

and seagulls, ever heartless,

scream at nothing.

His hooves trot out

sullen thumps on the wooden floor

and his curly forehead, innocently marked,

rises to meet its ghostly wreath.

The Sacred and the Profane

‘Lie down and give them a suck,’ the old man said,

pointing at the puppies ringed round the bitch

who reclined on her side in the straw.

‘You give them a suck, you old bastard,’

shouted the eight-year-old girl and they both

burst out laughing. While the bitch

with her silver coat and her glimmering eyes

clattered her tail in the golden straw

and smiled like a dolphin. And the puppies

swam at her breast in a cradle of straw

and the red heat lamp overhead

gave everything a sort of holy glow.

Waters

‘Hear water, see water, make water,’

my grandfather used to say. I proved him true,

all across the peat bog that day in Spiddal in spring,

tracing invisible brooks that filtered underground,

their sound bubbling to the surface later on,

thin streams trickling though the heather, frogs

holding out their faces to the sun. I dropped

many, many times (as you strode ahead),

then resolutely rose to carry on, until a brook

or eddy made me crouch again amongst the heather.

I remember the taxi driver who drove us (fighting)

from the pub to the holiday cottage late one night,

and how at first we couldn’t find the house

through the Mayo darkness and your temper.

A week later, tamed by sea views and Friesians,

we called a cab from Teach-Na-Mara

and he turned up again, the only cabbie in town.

He mentioned seepage, casually,

as he drove us on to Galway.

Oh, he let the truth trickle out all right.

A problem with property round here:

you’d buy a house, apparently watertight,

and in the first year the floors would seep,

seep with yellow liquid, rising from

the peaty ground below, like an unearthly

tide of dampness, cold, unhallowed.

Back in London, in my bed in Sadlers Wells –

you up above, asleep in your own room –

I dreamed my bed was floating off the floor,

floating on a rising pool of water, and all

the contents of the house spread out,

spooling from the windows and the doors

and drifting down the street. Your little bed

was cast out in the distance, a tiny dot,

and you upon it, slowly disappearing.

Then my grandmother waded into view, tirading

as she threw newly peeled potatoes in a pot.

She slammed it down upon a floating table,

put her hands on her hips, threw back her head

and, glaring at your disappearing bed, articulated:

‘I wouldn’t piss sideways for him, dearie!’

The Blush

He lived down the Littleton Road in his bender,

a homemade number, just a piece of green tarp

pulled over bent willow. There he tended his she-goat

and minded the fire with bit-sods of turf,

old pieces of timber. A gentle old man,

he came up to our farm only for water.

It fell into the pail from the tap in the yard.

As shy as a wild hare he’d nod his head,

we’d nod back at him, and then he would smile.

When the bucket was brimful, it was back to the bender,

to the shaggy white she-goat with vertical pupils