Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Corvus

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

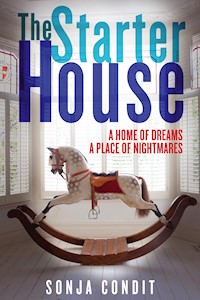

Every house holds a secret. Some secrets can kill. Lacey has found the house of her dreams: the perfect home to raise the child she's expecting. Soon, the beautiful sunlit rooms will be filled with joy. But the house doesn't want Lacey. The house is already occupied. Beneath the dark stairway lies a secret... No child has survived this house. No woman emerged in tact. Lacey has made a mistake. Now she must fight to survive it.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 503

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2014

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

First published in the United States in 2014 by William Morrow, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers

Published in trade paperback in Great Britain in 2014 by Corvus, an imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd.

Copyright © Sonja Condit Coppenbarger, 2014

The moral right of Sonja Condit Coppenbarger to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

Book design by Diahann Sturge

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities, is entirely coincidental.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Trade paperback ISBN: 978 1 78239 212 5E-book ISBN: 978 1 78239 213 2

Printed in Great Britain.

CorvusAn imprint of Atlantic Books LtdOrmond House26–27 Boswell StreetLondonWC1N 3JZ

www.corvus-books.co.uk

For Brent, Ethan, and Rebecca

Contents

Acknowledgements

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

Chapter Nineteen

Chapter Twenty

Chapter Twenty-one

Chapter Twenty-two

Chapter Twenty-three

Chapter Twenty-four

Chapter Twenty-five

Chapter Twenty-six

Chapter Twenty-seven

Chapter Twenty-eight

Chapter Twenty-nine

Chapter Thirty

Chapter Thirty-one

Chapter Thirty-two

Chapter Thirty-three

Chapter Thirty-four

Chapter Thirty-five

Chapter Thirty-six

Chapter Thirty-seven

Chapter Thirty-eight

Chapter Thirty-nine

Chapter Forty

Chapter Forty-one

Chapter Forty-two

Chapter Forty-three

Chapter Forty-four

Chapter Forty-five

Chapter Forty-six

Chapter Forty-seven

Chapter Forty-eight

Chapter Forty-nine

Chapter Fifty

Chapter Fifty-one

Chapter Fifty-two

About the author

Meet Sonja Condit

About the book

Author’s Note

Author Q & A

Reading Group Discussion Questions

Acknowledgments

THANK YOU, FIRST OF ALL, to the wonderful faculty at Converse College’s MFA program: my mentors, Leslie Pietrzyk, R. T. Smith, Marlin Barton, and Robert Olmstead; and to Rick Mulkey, Susan Tekulve, and Melody Boland, who kept the whole thing going. Thank you to Jenny Bent and Carrie Feron, for dragging me through the process, and to Nicole Fischer, for answering all of my questions so patiently. Most of all, I would like to thank my husband, Brent, for believing in me even when I doubted myself.

Chapter One

IT WAS ALREADY JUNE, and the Miszlaks still hadn’t found a house. Eric wanted guarantees: no lead, asbestos, mold, termites, crime, or trouble. Lacey wanted triangles.

“Triangles,” Eric said, as if he’d never heard of such a thing. They shared the backseat of the Realtor’s Tahoe, he with his binder of fact sheets organized by street name, she with her sketchbook, outside of their one hundred and eighth house. Lacey wanted to like it. She wished she could say, This is the one, I love it, for Eric’s sake, because he was getting anxious as their list of houses dwindled from the twenties to the teens, but she just couldn’t. This house with its square utilitarian front, so naked and so poor—if Eric settled for it, he’d be miserable by Christmas. They’d had enough of square houses, bland rooms no better than the motels she’d grown up in and the apartments they’d lived in together, houses without memory. They couldn’t live that way anymore, with the baby coming.

“Triangles,” she said, shaping one in the air with her hands. “Gables. Dormer windows. Look at that thing; a person could die of actual boredom. What about the one with the bay window?”

Eric flicked through his binder. “Bad neighborhood. Two title loan stores and a used car lot right around the corner.”

The Realtor turned in the front seat. She was on the phone with her office, trying to find another house in the neighborhoods acceptable to the Miszlaks. Although three thousand homes were for sale in Greeneburg County (many of them in the city of Greeneburg itself) this first week of June, the Miszlaks’ requirements limited them to Forrester Hills, on the northeast side of town. Lacey, three months pregnant and planning her baby’s perfect childhood, had mapped the attendance zones of the good schools. Eric drew a circle around his uncle’s law office, so he would have no more than a twenty-minute commute. The circles crossed only here.

CarolAnna Grey, the Realtor, had become steadily less blond over three weekends of driving the Miszlaks from house to house. Lacey felt sorry for her; she kept taking them to houses that failed one or more of their criteria, usually Eric’s. He had grown up in Glenaughtry, Greeneburg’s finest golf neighborhood. He had standards.

“This is my neighborhood,” CarolAnna said. “I’ve lived here all my life.”

“I’m not buying anything that’s walking distance from Austell Road,” Eric said.

“You’re going to have to open up your search.”

“No,” they said together, and Eric turned pages in his binder and said, “What about the blue house around the corner, Lacey? It had those windows you like.”

Lacey fanned her sketchbook and found her impression of the house: a toadstool with fumes rising from its gills. “Smelled of mold.” It smelled like a basement apartment with carpeting so dirty it sticks to your feet. She’d spent too much of her life in rooms like that already.

“Why don’t you just look at this house?” CarolAnna Grey said.

Eric and Lacey got out of the Tahoe. “We could look,” Eric said.

Lacey looked. It was a square, no question. She dug in her purse for the bag of pistachios. In the last three months, besieged by morning sickness, she had gained ten pounds, though the baby itself was smaller than her thumb; she had to eat all the time, dry salty food, to keep the nausea under control. She wandered to the corner, seeking shade.

The neighborhood was exactly right. She loved the way the streets curved. She loved the cul-de-sacs and the big trees, the gardens all flashed with pink and white as the last dogwood flowers withered in June’s green heat. She loved the big lawns prettified with gazebos, fountains, swings, wishing wells. A flock of little boys on skateboards flurried through the next intersection. Their voices hung in the air behind them like a flight of bells. She could live here forever, in the right house.

Forrester Lane curved counterclockwise, an arc of lawns and trees. She poured the pistachio shells back into the bag and walked along the sidewalk. It was broken in places, shattered from below by the heaving roots of oaks and maples. She liked that. It showed that the people who lived here valued trees more than concrete. Here was shade, under the biggest maple she had ever seen, effortlessly shielding two houses at once.

She looked up suddenly, her eye drawn to some motion not quite seen, and there was the house. She looked at it and her heart turned, like a key in a lock. Her house: a Cape Cod, dusty rose, its face naked and bruised. The shutters were piled on the porch, a sheet of plywood sealed the upper-right dormer window, tire tracks rutted the lawn, and a blue Dumpster stood crooked on the grass, filled with rolls of brown carpet and green foam-pad. A rust-stained claw-foot bathtub lay upside down on the porch.

Eric came up behind her and touched her arm to pull her away. “Look,” she said. It spoke to her. Its brokenness and emptiness called her, and the discarded carpet was a mark of hope. This house had been someone’s home; it had suffered and been damaged, and it was ready to be a home again. “Look, this is our house,” Lacey said.

“It’s a mess.”

“You’re not looking.” She pointed to the house on the left. Also a Cape Cod, it gleamed immaculate in the shadow of the big maple. Its siding was a yellowed cream, the shade of egg custard, and the shutters were golden caramel. Three white rockers sat at friendly angles on the porch, under hanging ferns. Someone had mowed the lawn in perfect herringbones. “They’re just the same. It could look like that, if we took care of it.” She couldn’t turn her back on this house; there was something in its expression, the angle of the dormers, so quizzical and innocent and appealing. It needed her. “It’s just so cute.”

“Cute? Be serious. The down payment, it’s all the money we have.”

The porch steps were broken. Lacey got her left knee onto the porch and hauled herself up, ignoring Eric’s protests. The front door, scraped of its paint, swung open to her hand, and she walked in.

The entrance was surprisingly wide. To the left, an open arch led to the formal living room: two big windows and a gray marble fireplace. The floor was bare wood, with a sander standing in the middle. Lacey was glad the carpets were gone; they must have been horrible. To the right, another open arch, and a smaller room, with the same big windows. A roll of carpet stood in one corner, its underside stained in broad circles of brown and black. Straight ahead was the bright heart of the house, a staircase beautiful even under its mud-colored Berber. A porthole window, a quartered circle, shed yellow western light down into Lacey’s eyes. The last six steps broadened and curved out and back, with the lowest step describing a complete circle around the banister post.

Lacey could see her someday children there. They would sit on that round step in the sunshine. She saw a boy folding paper airplanes, which he meant to throw from a bedroom window. She saw a girl leaning against the post with her head bent over a book. The girl tucked a lock of hair behind her ear. She read as Eric did, biting her upper lip, her eyebrows tucked into a frown. The light hid their faces from her, but she already knew them. Someday, here. They had chosen their home in this house.

Eric took Lacey’s elbow and pulled her out of the house. “You can’t just walk into someone’s house,” he said. “You don’t even know if it’s for sale.”

Lacey let Eric help her off the porch, where CarolAnna Grey caught up with them. “This is the house I want.”

“You don’t want this house,” CarolAnna said. She looked as if she could say more, but Lacey didn’t want to hear it. After one hundred and eight shoeboxes, she knew a real house when she saw it.

“We don’t want a fixer-upper,” Eric said. “I won’t have time to work on it, and you can’t, not by yourself.”

“Someone’s fixing it up already. Fixing it to sell.”

“You can’t know that,” Eric said, but Lacey knew it by the house’s emptiness. Her someday children would never have appeared in another family’s home. A family would have moved their furniture from room to room, not taken it all away. This house was getting ready for a new life.

The maple cast a green darkness over the lawn, a whisper of busy hands, and CarolAnna shuddered and moved away from it. “There’s a real cute condo in a new development west of the mall,” she said. “With a swimming pool.”

Eric walked backward across the lawn, squinting upward. “Roof looks good.”

“They’re getting ready to paint,” Lacey said. “If we make an offer fast, we can choose the colors. Inside and out.”

If the shutters were green, dark mossy green … She wanted a green door, like the door of Grandpa Merritt’s house, which had closed behind her forever when she was six, her last real home. They’d paint the baby’s room sky blue and stencil stars and butterflies on the ceiling. They could do whatever they liked and not have to ask a landlord’s permission or worry about the damage deposit. They would have a dog. She added a golden Labrador to her vision of the someday children on the staircase; then she pulled out her sketchbook and roughed in a drawing of the house’s face and the maple.

The house looked happy in her picture. This was why she preferred to take sketches of the houses, rather than photographs. Snapping a picture was quick and easy, but the drawing told the truth, like the difference between e-mail and real conversation, websites and books.

“You could rent an apartment and wait a couple months,” CarolAnna said. “Come July, there’ll be thirty more in your area.”

“Is there something wrong with this house?” Eric said.

Next door, in the twin Cape Cod, the front door opened and a tall white-headed man came out onto his porch with a watering can. He looked over and said in gentle surprise, “Well, it’s you, CarolAnna Grey. This isn’t Tuesday.”

“It’s Sunday.”

“And how’s little Madison; is she practicing?”

“Not so you’d notice.”

The tall man courteously left a space in the air for CarolAnna to introduce Eric and Lacey. She set her mouth and said nothing. Lacey stepped into the painful silence, folding her sketchbook open on the picture of the house, and said, “I’m Lacey Miszlak and this is Eric. What do you know about the house next door?”

“Harry Rakoczy.” He smiled at CarolAnna. “I’ve known this one since she was tiny, and now her little girl’s taking lessons with me. Violin. You’re interested in the house? I’m getting ready to sell.”

Lacey said, “Yes,” but Eric said, “Maybe. What’s the history?”

“Harry, they don’t want it.” CarolAnna touched his arm. He looked at her hand until she let go. “It’s not right,” she said.

Harry ignored CarolAnna and smiled at Lacey. “It’s been a rental for years. Roof’s two years old, heat pump’s practically new, and I’m renovating.” He waved his watering can at the old bathtub. “Get that thing out of there. It’s time.”

“Harry,” CarolAnna said. She glanced at the upstairs window of the empty house and moved away, as if someone might see her. “Harry, no. She’s pregnant.”

He set down the watering can and smiled at Lacey. “Looks good on you.”

“The second trimester begins today,” Lacey said. “And my due date’s Christmas.” She told everybody she met, now the first trimester was over and it was safe; she wanted the world to know.

“What are you asking?” Eric said. He was never lost, not in a confusing map or a meandering conversation. Eric always knew where he was going.

“A hundred ten.”

Lacey was surprised. The other houses in Forrester Hills ranged from a hundred fifty to over two hundred.

“Harry,” CarolAnna said anxiously.

“Is there something wrong with the house?” Eric asked again. Lacey wished he wouldn’t. The house was obviously perfect. They could deal with anything—termites, mold, radon—but they could never make an ugly house their true home.

“Yes,” Harry said to CarolAnna, “is there?”

CarolAnna licked her lips, then wiped her mouth with the back of her hand. She looked at the bathtub on the porch and said to it, “People died here.”

“People die everywhere,” Lacey said, though the words gave her a shiver. Poor house, no wonder it was lonely. “When did it happen?”

“A long time ago,” Harry said. “It was very sad.”

“If it doesn’t bother you,” Eric murmured, and Lacey shook her head—she didn’t care at all. These houses were thirty, forty years old. People must have died, had babies, gotten engaged, married, divorced, hurt each other in a thousand ways, reconciled and forgiven, passionately hated and desperately loved; if you abandoned a house whenever something significant happened, people would live in tents. This house had known life.

“Ninety-five,” Eric said to Harry. “Pending the inspection.”

“Ninety-five,” Harry said thoughtfully, as if he might actually consider the offer—it had to be worth a hundred seventy at least. Lacey felt she should tell him so. Just then a green Hyundai pulled into his driveway. “Here’s Lex and the baby, I’ve got to go. CarolAnna, send me the offer and we’ll talk. And you tell your Madison, ten minutes of bow exercises every day, and I’ll know if she hasn’t done it.”

A tall man got out of the Hyundai and unbuckled a baby from the back. He stooped under her weight, and she seized two fistfuls of his colorless hair and pulled his face up. The baby’s voice pealed in a high wordless cry of greeting, bright as a bird.

Harry shook Eric’s hand again and hurried back to his own front door before Lacey had a chance to ask about the bathtub. She loved old-fashioned furniture, and the claw-foot tub was beautiful. She wanted to know if it was rusted out, or if it might be refinished and reinstalled. While Eric and CarolAnna returned to the Tahoe, Lacey picked a few flakes of white enamel off the tub and rubbed the rusty iron beneath. The tall man stared at her from Harry Rakoczy’s front porch, the baby squalling impatiently, until Harry urged him inside.

The Tahoe honked. “Come on,” Eric said. “She says there’s a new subdivision zoned for Burgoyne Elementary.”

Lacey patted the bathtub. She already knew everything that mattered about the new subdivision: small lots, no trees, the houses all alike. “You stay right here,” she said to her house. “Wait for me.” They’d have to be quick; if Harry meant to accept Eric’s offer—ninety-five thousand, practically giving it away—they’d have to grab the chance. There was no time to waste on condos and subdivisions.

Chapter Two

SEVEN WEEKS LATER, on the first Tuesday in August, the Miszlaks moved into 571 Forrester Lane. CarolAnna Grey got over her inexplicable reluctance to sell the house when Harry Rakoczy added an extra percentage to her commission. He told the Miszlaks he needed to sell because he had retired from the orchestra and would soon be moving to Australia to be with his son’s family. Lacey was disappointed. She’d been looking forward to taking her baby next door for violin lessons with the old man in five years.

Though Eric called it their starter house, Lacey planned to live in it for ten years and maybe forever. She wanted her someday children to attend the same school from kindergarten through fifth grade, to have teachers who’d seen them grow and friends whose toddler birthday parties they’d attended. Her own childhood had been furnished with cardboard boxes and duffel bags, always moving, always ready to move. Lacey had attended eight different schools, and she couldn’t count the moves or even define them. There were times they’d slept in the car. Was it moving if they parked in a different spot? Did a shift to another room in the same shabby motel count as a move?

She knew what she wanted for her baby. She wanted the home that had been hers when she was six, when she and her mother had lived with Grandpa Merritt in the white house with the green door and the big magnolia tree. Grandpa Merritt’s house, like 571 Forrester Lane, had a smiling face, a sense of welcome. She wanted to be able to walk in the dark and recognize the sound and texture of every room.

Everything would be different when they were settled in the house. She hated moving, but if she had to do it, it might as well be in August, her New Year. For Lacey, a teacher, January was the trough of the year, when the children faced her across a barricade of desks, both sides exhausted beyond compromise. Now in August, the crayons were fresh in their boxes, bright as the children themselves. Every year, she bought new sketchbooks, leaving the last pages blank in the old ones. As soon as they moved in, she’d go from room to room, sketching doors and corners, making it her own.

They’d driven the route a dozen times in June and July, viewing the house, meeting with the Realtor, the bank, the lawyers, Harry Rakoczy, and the painters. They’d both driven it yesterday, coming up in two cars to leave Eric’s Mitsubishi in the Greeneburg U-

Haul parking lot. It had always been an easy drive; they’d never seen traffic like this.

Highway construction delayed their arrival until seven thirty. Eric had planned for noon. Being late put him in a terrible mood, and if they didn’t deliver the empty U-Haul by nine, they’d be charged an extra day. “Let’s get started,” Eric said. “We can pile everything on the lawn for now. Just get the van empty.”

“Can’t we pay the fifty bucks and do it in the morning?”

“I’m not paying just so we can park overnight. Come on. I’ll get the books and furniture, you get the light stuff. Forty minutes and we’re done.”

“Can we give it a rest, this once?”

No, they could not. He was right and she knew it; she wished he wouldn’t be so completely right, all the time. He backed the van into 571’s driveway. The west was fat with gold, and most of the houses on the street already had a few lit windows. Harry Rakoczy’s house was dark and his car was gone. Lacey had hoped Harry could talk some sense into Eric, but they were on their own.

“I’d rather unload the futon and finish in the morning,” she said.

“We can do this.” Eric yanked at the van’s back door. It accordioned up into its slot and stuck halfway. He started pulling out boxes and laying them on the lawn. “Get the light stuff,” he said.

Lacey leaned into the van, breathing the smell of their lives, the years of their young-married student poverty: clothes washed with never quite enough cheap detergent, the orange Formica dinette, the futon Lacey bought for fifty dollars from an old roommate. The smell of garage sales and thrift shops, old textbooks, off-brand coffee, slightly irregular sheets worn thready at the hems.

She grabbed the nearest box, which gave a glassy jingle. She balanced it on her belly bump long enough to get her right hand under it, turned toward the house, and tripped over the curb. As she stepped high to get over it she could not see, a bell rang. Surprise made her stumble, and she caught her balance, the box chiming in her arms; she hoped nothing had broken. A child rode a bicycle along the sidewalk. She hadn’t heard him coming until he rang his bell, though the ticking of the wheels was loud enough. He had sprung out of the grass in the tree’s shadow. Her heart closed and opened. She took a breath and talked sense to herself: Just a kid on the street, settle down.

Her teacher’s eye said Nine, but small for his age: a boy with fair, wavy hair and a gray T-shirt stained with long rusty streaks. Trouble at home. Something about the way he stared straight ahead, something about the grip of his small fingers on the handlebars. She hoped he didn’t live too close. He rode his bike along the sidewalk to the edge of Eric and Lacey’s new property, still marked with a row of orange survey flags—he rang the bike’s round bell once, ting, and then turned and rode to the row of flags on the other border. He braked by jamming his heels into the sidewalk and rang the bell again. Ting.

Lacey started across the sidewalk and there he was again, suddenly, pedaling in front of her. His shoulder brushed the box, and she dropped it. Salad plates and dinner plates, bowls and coffee mugs, hit one another in one great shout of destruction. “Do you have to do that?” Lacey cried. “Right here? Do you have to?”

The boy stared at her, a look of challenge, like a dog too long chained: Come closer and see if I bite. “Who asked you to come here talking to me?” he said. The strange ferocity of his response made her step back and raise her hands.

Eric ran to the box. “I said leave it alone!” He opened the box to a mass of splinters and shards, with one intact dinner plate on top from the stoneware set they had bought at the Dollar King last June, on sale for nine dollars (marked down from fifteen). “These were good plates. They could have lasted us for years. Look at this, all this waste.” He laid the pieces out to match the bigger parts together and see if some of them could be saved. White ceramic dust drifted in the bottom of the box.

Lacey could hardly believe how a single impact destroyed the dishes so completely. “We can get another set,” she offered. “They were cheap.”

“Nothing’s cheap when you’re living on borrowed money. You don’t know,” Eric said. So angry, like it was her fault, the traffic eating up the day—like she’d dropped the plates on purpose. “You don’t know what it’s like,” he said. “Just this. Just everything. But if it’s what you want, fine, we’ll do what you want, like we always do. Buy new plates. Buy new silverware while you’re at it. New tablecloths, why not. Spend a hundred dollars. Five hundred. Whatever, what difference does it make, I don’t care.” He pulled the accordion door down in its slot so hard it bounced, and he had to catch it and force it down again.

“Wait,” Lacey said. The day had been just as hard on him as on her—harder, because he’d been driving. “We can finish. We’re almost done.”

He got into the driver’s seat, and the slamming door was his only answer. At the corner, he stopped and signaled before turning left. His carefulness so exasperated Lacey that she had to chew on her knuckles to keep from shouting after him.

She sat on the grass, holding her knees and rocking, with a dozen fragmented conversations rattling in her mind. You should have known—you think you know so much—I could have told you—why don’t you ever listen to me? Another stupid argument, their fourth this week. He said she spent too much, they had no money, why couldn’t she understand—which was good, coming from a guy who’d grown up with all the money in the world, a two-million-dollar trust fund and a vacation home on the Isle of Palms, until it all disappeared. And he was telling her what poverty was like, as if he knew. This wasn’t poverty; this was just a temporary low point between her job ending and his beginning. They were building up some debt, but it would all be gone in two months, except the student loans. If they couldn’t handle the stress of moving, what kind of parents were they going to be?

She breathed quietly and listened to the maple. Eric always left when they fought. When he came back, he would be all love and sweetness, and neither of them would mention this fight again.

She lay back. After a while, she began to hear the sounds of the grass. When the wind brushed her face, the blades rubbed against each other, sharing friendly news. Bees worked the blossoms of the tall purple clover and the short white clover, the small sweet buttercups. A wood dove called, “You-u. You-u.” Children’s voices rang, far off. The ticking of wheels gathered in the rustling stillness. And the little boy rode his bicycle up and down the sidewalk, turning at the property line.

The whirring wheels seemed loud but distant, like a recording played back at too high a volume, and each time the rhythm of his stop and turn was identical, his heels bouncing and then scraping on the sidewalk, the wheels slowing, his quiet grunt as he picked up the bicycle and turned it, and then the bell at last: ting. How did he do it exactly the same every time? More and more, Lacey felt she was listening to a recording, and not a real event. If she opened her eyes—which she would not do, nothing could make her look—she would see the sidewalk empty except for a boom box playing a CD on infinite repeat: Ting. Ting.

Chapter Three

THE HOUSE WAITED, its windows golden in the evening light. Lacey yearned to be inside, to open the windows and let the fresh air carry away the smell of new paint, to decide where to put the futon—opposite the window, or diagonally in a corner? She’d have to wait for Eric to come back with the keys. She lay on the grass with her hands lightly woven over the belly bump, sensing the odd fishlike twitches, the clear sense of something in her that was not herself, a stranger in the dark red heart of her life. Her favorite pregnancy website, YourBabyNow.net, said that at eighteen weeks she wouldn’t feel the baby, but she’d felt it from the first day. For two months they tried, and halfway through March she woke up one morning with a blunt, foreign feeling in her cervix. Something new, hello, little stranger. She waited two weeks for the test, but she knew, and she felt it now, though the website said the baby was no bigger than a large olive. She breathed quietly, and the child knocked and twisted, and finally lay still. Even in its stillness she felt it, the hard wall of her womb under a half-inch shield of fat.

Someone alive, someone new. On the day she took the test—the first day of her first missed period—she had parent-teacher meetings, three hours of parents, variously nervous, belligerent, businesslike, guilty, proud. She discussed handwriting and spelling, recommended math-game websites. The only meeting she remembered was the last, a young mother who sat in Lacey’s classroom with her three-month-old daughter on her lap. The baby was bald except for a tuft of transparent hair. She wriggled and murmured, and her round eyes never left her mother’s face. Ten minutes into the meeting, the baby began to fuss. The mother, never missing a word, lifted the baby up to her face, and the baby lunged forward, then latched on and suckled on the mother’s chin. Lacey had never seen a gesture so intimate. She forgot what she was saying about the woman’s older child and simply blurted to this stranger, “I’m pregnant.”

The young mother shifted the baby to her shoulder and rubbed the back of the round fuzzy head. “Your first, right?” she said. “It’s worth it in the end.”

The life inside Lacey was a mystery, not a communion. In its first weeks, this child, a creature smaller than a fruit fly, took her body by storm, three months of nausea. The baby filled her ankles with water, unstrung her knees, and tormented her with a starving hunger worse than she had felt on even the strictest diet.

The world was full of other people’s babies, so beautiful, with their big round eyes; they looked at her with a deep gaze, knowing something she had long forgotten. Even if she’d known it would be this hard, she would have welcomed it, the someday baby coming closer every day. But the struggle was hers alone. Not even Eric could understand.

Cloud shadows shuttered across her eyelids, cool, warm, cool again, and a small wind walked around her, plucking at her hair with teasing fingers. A darker, nearer shadow fell over her. She became aware of presence, the sound of breath, a weight in the air. How vulnerable she had made herself, lying on her back, half asleep, in a place where she knew nobody. She opened her eyes.

Harry Rakoczy from next door, whom she had last seen in Eric’s uncle’s office during the closing, loomed over her like a mild-mannered predatory bird, dangerous only to the fish in his shadow. Most people loomed over Lacey, but Harry was at least a foot taller than she, though he couldn’t weigh a pound more—probably five pounds less.

She felt she was seeing him for the first time. Before this, she’d looked at him through the house, her desire for the house; he was the owner, the opponent, the obstacle, her ally when Eric got cold feet; his was the signature that made the house hers. Now she looked at him as if she meant to draw him. He had the habitual stoop of the unusually tall. The length of his strong narrow hands and the height of his thin face rising to the black widow’s peak of hair made him seem even taller. She gathered herself out of the grass, brushing the dry bits of thatch off her clothes, hating to be caught like this, sweaty and scruffy, waiting for Eric to come home.

“Are you okay out here?” Harry said.

“Eric took the van and he forgot to leave the key.” She was appalled to feel herself on the verge of weeping. “And I left my phone in the van, so I can’t call him. It’s just the whole day, I don’t know. Moving. And then we got stuck in traffic forever.”

“Moving is hard,” Harry said. “Come inside and have some tea.”

In five minutes, Lacey was in Harry’s kitchen with a glass of sweet tea. His house was everything she hoped hers might someday be. The maple floors shone, and every piece of furniture had its own light, from the red sun shining off the polished tabletop to the rainbows flaring from the beveled edges in the china cabinet’s doors.

He seemed restless in the beautiful room, putting down his glass and picking it up again, fidgeting with a dishcloth. “Come to the front room and see where I teach,” he said. She thought he’d been about to say something else and had changed his mind at the last moment.

In the front room, she found the same glossy oak floors, two wooden music stands, a framed five-by-six-foot charcoal drawing of a young woman playing the violin in a whirl of long hair, and a collection of amethyst carnival glass on the mantel. Harry raised his glass of tea to the drawing. “My sister, Dora. When she was very young.”

“It’s beautiful. Who drew it?”

Harry’s face smoothed to a deliberate flatness, a public face, neutral as the image on a coin. “Her husband. They lived next door, in your house.”

Lacey nodded, abashed, unable to fathom what she had done wrong. She bounced on her toes and wished she could find a way to leave without seeming rude. She followed Harry to the kitchen and accepted more tea. “Did the painters do a good job?” he said.

“I can’t get in.” Eric could at least have left the key. She forced her mind away from the house, still withholding itself from her after all those weeks, the forms they’d signed, the down payment, and she couldn’t even get inside. A thought came to her. “The little boy on the bike. Who’s he?”

She didn’t like the way he’d turned at the property line and kept himself so exactly in front of her house, as if he had a right to be there. It made her uneasy. Harry looked like the neighbor who knew everyone’s business, the plant waterer for friends on vacation, the third name on everyone’s emergency contact list. Lacey’s mother depended on people like this to hold her mail when she was vagrant. Lacey hoped the boy was someone’s grandson visiting, or the child of renters who were leaving in a month. Someone she wouldn’t have to worry about.

Harry set his glass down hard in surprise, and tea spilled onto the bright tabletop. “You’ve seen him?” he said.

“You know the one I mean?” Lacey was disappointed; if Harry knew the child so well, he must live nearby and be a problem in the neighborhood.

“Children on bicycles, they come, they go….” He busied himself with a napkin and wouldn’t meet her eyes.

She leaned forward across the table. “Does he live on the street?”

Long after the table was dry, Harry kept rubbing the napkin in circles, staring at his hands. At last, he looked across the table, but his eyes were fixed on Lacey’s glass, not her face. “No. He’s never shown himself to me.”

Lacey had seen this kind of evasion when she asked other teachers about certain children. If the child’s first-grade teacher said, I didn’t know him well or he’s probably changed since then, she knew she had trouble. Refusal to answer was the answer. “Thanks for the tea,” she said. She’d watch for this neighbor boy and get to know him; trouble was her specialty. “I’d better get back. Eric will be home soon.” Maybe—she hoped.

“I’m thinking, CarolAnna changed the locks, but did she get the back door?” He opened a drawer next to his sink. “Key, key. Let’s see if this works.”

She followed him out the back door, looking over her shoulder for one last glimpse of his sister, Dora, with her violin in the front room, her predecessor in the house. They walked between the two Cape Cods, underneath the maple where no grass grew. New mulch left a sulfured scent in the evening air. The back lawn was mowed in diagonals down to the row of cypresses, and around the brick patio the sentry boxwoods stood neat and tight. Lacey knew that Harry had been maintaining the Miszlaks’ yard along with his own. She hoped she and Eric would be able to keep it this nice.

Harry offered her the brass key. “Give it a try.”

Lacey wriggled the key into the lock. She pressed it hard, and something pushed back. Her hand jerked with a reflexive shock, as if she’d touched a centipede. She hated the touch of manylegged things, so wrong, unnatural. The key dropped to the doorstep. When she picked it up, it was warm in her hand, and it wouldn’t enter the lock at all.

“No,” she said, suddenly furious. The whole bitter, frustrating day came down to this: the door, the key, the lock. She wasn’t about to let Eric find her waiting to be let in, like some stray. She had found this house and chosen it—it was hers. She forced the key. The lock yielded slightly, then seized and would not let the key release or turn.

“Wait,” Harry said. “I’ll go get the WD-40.”

It was too much. Her house had shut her out—her house, the house she had loved when it was broken and dirty—now clean and beautiful, it shut her out? No. She found a chunk of gray stone under the boxwoods and hammered the window, ignoring Harry’s protest. Her anger felt entirely reasonable to her; one way or another, she was going in. The glass clung to the frame for three seconds before releasing to shatter on the kitchen floor. She put her hand through to reach the inner lock, and something bit her—no, it was broken glass in the window frame. Blood ran down her palm from a diagonal gash, shockingly cold, as if she’d reached into a freezer and grabbed the coils. She gripped her wrist and looked at Harry, so disoriented by her own behavior that she could not imagine what to do next. And the angry thought, rooted in her mind as deeply as the baby in her body, pulsed relentlessly, My house, mine, mine.

“Wait,” he said. “Don’t go in.” He hurried across the grass to his own back door.

She saw a roll of paper towels on the kitchen counter, so she reached through the broken window and unlocked the door. Fat handfuls of blood spread on the newly grouted floor. They had chosen light blue tile for the floor and gray granite for the countertops. She hoped her blood wouldn’t turn the blue grout black. She squeezed her hand around a clump of paper towels. Numb cold rayed through her wrist.

Inside, the dining room and hallway were unexpectedly dim with a darkness gathering like water in a cup, and pressing into Lacey’s eyes and filling her throat. Her teacher voice, the careful adult Lacey, warned her to stop, go out and wait for Harry, but she ignored it because the house was hers. Nothing could keep her out. She clenched her injured hand between her breasts and reached out with the other hand to feel her way.

She could not understand this darkness, here where the lowest step turned in a full circle and she had seen her someday children and their maybe dog in the bright afternoon. Evening light came in through the two windows in the living room and reflected off the newly polished and sealed floors, a sheet of brilliant amber. In the kitchen, red sunlight glittered in the granite’s mica flecks. Yet no light reached here, where the stairs began, though it should have poured in a shower of gold down the porthole window. She looked up to see what was wrong—had the painters blocked the window with cardboard and forgotten to remove it? Was the glass broken and boarded up?—and she saw nothing, not even darkness. A mist pressed against her eyes, and her mouth tasted of cold gray water, the taste of fear.

There was a step on the front porch, too light for Harry, and a hand tapped the door. Lacey held her breath and pressed her hand over her breastbone to muffle her rushing heart. She felt like a child put to bed in a strange room, knowing silence was safety, head under the blankets no matter how hot, suffocating on terror and her own used breath. But the teacher voice said, It’s time to act like a grown-up, and the hand tapped again. Nothing to be afraid of, it said, just a neighbor at the door.

“Coming,” Lacey called. Something caught her ankle. Something that gripped and squeezed. Her feet flew out behind her and she tumbled forward, twisting as she fell.

She landed hard on her right side and curled around the belly bump. “No,” she said. “No, no.” This could not happen. She held her breath, keeping the child in through will alone; she clenched her fists, regardless of the pain in the slashed palm.

The back door opened, and with Harry’s entrance, light flowed into the hall, rising from the polished floor. The porthole window burned. “Lacey? Where are you?”

“I fell.” The middle of her body tightened, relaxed, and tightened again around a feeling too dense and slow to call pain.

“Are you hurt?”

Something touched her thigh. “I’m bleeding.”

He took her right hand and pulled her fingers away from the red clot of paper. “You’ll need stitches.”

“No. I’m bleeding.” Lacey reached under the pink dress to touch the thing on her thigh, soft and insinuating, a wet feather, a tickling tongue, the faintest sticky stroke of warmth sliding on her skin. “Ambulance,” she said, her voice perfectly steady. Her heart hummed in her ears, and she kept her face stony. If she let go, let her mouth shake even once, she would fall apart and the baby would die. She tightened her thighs to hold everything in, blood and baby and all. She would not allow this to happen.

“This is too soon,” Harry said. He reached down to take her elbows, as if to pull her to her feet. She shook her head. His hands jumped away from her.

“Ambulance,” she said again. She showed him her left hand, the blood on her fingertips. “Please.”

Chapter Four

AFTER TEN MINUTES in the emergency room, Lacey was wheeled into a semiprivate room in Labor and Delivery. Pink and blue balloons floated above the doorknobs in the hall, each announcing someone else’s baby. She waited for a long time and no one came to tell her if her baby was alive or dead. If only she had her phone so she could call Eric—even if she had the phone, the battery was probably drained; she was forever forgetting to plug it in. It made Eric so impatient with her; he was always waiting for her to call, or trying to call her. Where was he? She closed her eyes and whispered to the baby, “Hold on, hold on,” and still the blood trickled, sticky and slow.

The door opened. “The cut’s closed up on its own,” Lacey said without opening her eyes. “There’s no point stitching it now.” They’d brought her into this room and left her here, surrounded by other people’s happy balloons, and didn’t care enough to come in with so much as a stethoscope, let alone an ultrasound. It was so unfair, and she was all alone; she needed help and no one cared. Not even Harry had come with her, and where was Eric? Her underwear was soaked through, and every time she touched it, the blood was still warm and fresh.

“Lacey, what did you do to yourself?” Eric, at last. “All you had to do was sit there in the shade. I wasn’t gone for fifteen minutes, and I come back and there’s the window broken, blood all over the floor, anything could have happened, I had no idea.”

“You shouldn’t have left me.”

“I was only gone a minute. Just to get my temper under control. My parents used to fight about money. They went on for hours, shouting, breaking things. I don’t want to be them.”

“Then you can’t leave. You have to stay and talk to me.”

He sat on the bed and lowered his face to hers, kissed her forehead, her eyelids, and her mouth. His face was wet. He was crying, right out in the open, defenseless. “Lacey, can you ever forgive me? I am so sorry.”

It terrified her, the way Eric could turn like this. He dropped everything all at once, all his competence, his confidence, everything that made him right, and gave her his naked heart, a thing she was afraid to see, let alone touch. No one else had ever seen him like this—and now, when she didn’t know if the baby was dead or alive, now she had to comfort him. She knew he needed more, but she couldn’t make herself speak.

His face sank into her neck and he lifted her shoulders into a dense, trembling embrace. “I was so scared,” he whispered into her skin. “I thought you were dead, I thought the baby was dead.”

And he assumed the baby was fine, that she’d taken care of everything while he was out soothing his own hurt feelings. “Nobody’s looked at the baby yet,” she said. “Nobody’s told me anything.”

He pushed himself off the bed. “They haven’t looked? Are you still bleeding?”

“I can’t tell.” Her voice cracked, and she closed her mouth hard. As the blood dried, her skin tightened and itched. She didn’t want to touch whatever was happening under the sheet, fearing to find something more than blood—a tiny curled body, already cooling in the mess. No; her fingers imagined it, but she shut her mind. She wanted a doctor. Someone who would tell her quickly, as quickly as the pregnancy test: yes or no.

“I’ll be right back,” Eric said.

He returned in four minutes with ultrasound machine and doctor in tow, a dry small woman with pearl earrings and the cleanest hands Lacey had ever seen, fingernails like bleached shells, palms pure white. “Let’s look at you, Mrs. Miszlak,” she said. The gel was cold, and the doctor slid the wand over Lacey’s belly and said brightly, “There’s the heartbeat.”

“Are you sure?” Lacey couldn’t let go of the fear so easily. The doctor touched a panel on the machine, and the heartbeat sounded through the speakers, a quick watery hush-hush, hush-hush. Lacey cried without noise, weak in relief, pressing the backs of her hands against her cheekbones.

Eric sank into a chair. “Thank God.”

“You want to know what you’re having?” They nodded. She slid the ultrasound wand over Lacey. “Definitely a boy.” It looked like a star map to Lacey, a sweep of cloudy constellations, gray in a black sky. “There’s his profile. Look at that pretty face. Now, about this bleeding.”

The ultrasound machine printed out a picture, and Lacey saw the child in the gray stars, the large curve of his head, hands under chin, thin legs drawn up and crossed. There he was, a real person, already alive. It was good to think he instead of it. She was bleeding, the doctor told her, because the placenta had partly torn away from the wall of her womb. There was no surgery and no medication, no help but rest, and no promise that rest would help. If the placenta tore away—unzipped, the doctor said, if it unzipped itself from the wall—the baby would die. If it scarred, the baby would survive. She spoke as calmly as if she were reading a recipe. “We want to keep you overnight for observation,” she said.

Lacey wished the doctor would leave the machine hooked up to her so she could listen to it all night. Hush-hush, hush-hush. Even more, she wished the doctor would stay and interpret the pictures and sounds. Still alive, the doctor would say every hour, on the hour. It’s a boy, and he’s still alive. “Will he be okay?” Lacey asked, and the teacher voice admonished her, Don’t ask if you don’t want to know.

“Most likely,” the doctor said. “You relax.” She left, taking the ultrasound machine with her. Lacey put the picture on the bedside table. Every few seconds, she touched it, imagining the baby’s heart, hush-hush.

Eric slumped in the chair with his hands over his eyes. After a while, he said slowly, with a weight in his voice, “I have to get down to the office.”

“The office?” Resentment flowed up Lacey’s left arm into her heart. “You’re not staying?”

“I’ve got to. Uncle Floyd’s given me a dozen divorces, and I’ve got to get up to speed.” He stroked her belly and then bent down to kiss her. She let him do it, holding her lips stiff under his mouth. Then she was sorry, and it was too late, he was gone, because his work was important.

Eric’s work was always more important than hers; when they were dating, he would cancel on her without a second thought if he had a big test or paper due, and she never did. Even when she was working to put him through school, his work was a career and hers was a job. The first thing he said when Uncle Floyd offered him the position was now you can stay home till the baby starts school, as if that had been their plan all along. She thought not, and she’d let him know in good time.

Eventually, the nurses fed her a flat gray piece of turkey, or possibly a boiled sponge, along with a dinner roll, boiled carrots, boiled spinach, and a boiled potato, with cherry Jell-O. She drowsed, propped up in the bed with her hands folded over the belly bump, feeling her son spinning and dancing inside her. “We’ll go home tomorrow, baby,” she said. “We’ll get moved in; I just have to unpack a few boxes.”

The door opened. If it was another nurse with another needle, Lacey would beat her off with the dinner tray. But it was the bicycle boy from Forrester Lane, little mister trouble-at-home. “I could help,” he said. “Maybe I could.”

Grayness whirled over her, the same strange gray panic that had closed her sight on the stairs; she disappeared into it. This child should not be here. It was wrong. She searched for the call button, but it had slipped away and its cord was caught in the machinery of the bed.

“Why are you here?” she said. She found the cord and pulled it sideways. It gave an inch and then stopped.

“My mom came here.”

“Your mom had a baby?” Though Greeneburg was a small city, it surprised her to land in the hospital at the same time as some near neighbor. She yanked the cord, and the call button jumped into her hand. Its solidity in her palm gave her strength. Why was she so flustered by this ordinary child? Stupid hormones. “Why aren’t you with her?”

“I can’t find her.”

The child looked terrible, dirty around the hairline and neck, clean-faced as if he had been washed carelessly and against his will. He sniffled and smeared the back of his hand against his nose. “Have you been lost for long?” she asked him.

“Ages. They left me and they took the baby and I can’t find them.”

“I’ll call the nurse.”

“They’re no good. Nobody listens to me.”

“I’m listening. What’s wrong?”

His body swayed, as if he meant to run over to the bed and cast himself upon her. He held himself tense by the door, twisting his dirty hands. “It’s the baby,” he said. “She cries, and Mom’s real tired all the time, and I only wanted to help.”

Parents never knew how sweet their children were. At conferences, when Lacey said something good about a child, especially a boy, the parents often responded with Are you sure that’s my kid? right in front of the child. So this little guy wanted to help, and his parents wouldn’t let him. Probably they were afraid he’d drop the baby.

“Let me buzz the nurse; all you have to do is tell them your name and they’ll take you straight to your mom’s room,” she said.

“No, they won’t. They never will.”

Lacey’s eyes flooded for his sake. It was partly the hormones that made her weepy, partly this one dirty, hopeful, affectionate child, this one loving and wounded heart, the emblem of so many. She pressed the call button, but when she said, “They’re coming,” the child was gone.

“What do you need here, Mom?” the nurse asked.

“There was a little boy. He couldn’t find his mother.”

“I’ll find him.”

Lacey waited for her to come back and tell her the child had been found. She never did. The hospital hummed and whispered, and every time Lacey fell asleep, a door banged, or someone’s footsteps ran fast and hard outside her room. She counted boxes, everything that needed to be unpacked, all that work she had to do tomorrow, the empty house waiting to be filled. She drifted off and spent the night working in her dreams, unloading box after box after box of things she didn’t even know she owned, opening door after door in a house that had no end.

Chapter Five

THE NEXT AFTERNOON, when Eric brought her home in the Mitsubishi, she discovered he had done more than turn in the U-Haul and pick up the car. He opened the front door and Lacey stepped into a room she didn’t recognize. He laughed at her surprise. “The magic of same-day delivery,” he said. “You like it?”

When they were dating and he’d had money, Eric had been the master of romantic surprises. He took her on the most astonishing extravagant dates: a balloon ride, a cabin in the Smokies, a cruise to Alaska. Even when the money went away, he’d live on peanut butter sandwiches for two weeks to save his lunch budget for a special meal. And now he’d furnished the house. He’d bought real furniture: sofa, loveseat, and chair in dark red leather—end tables and a coffee table, dark walnut—and the most perfect lamps, ornate brass columns with gold linen shades and tassels. Everything had ball-and-claw feet. Her whole life, she had longed for furniture with ball-and-claw feet, furniture that announced itself: I am here, and here I stay.

“If you don’t like it, we’ve got three days to exchange it,” Eric said.

“It’s perfect. Oh, bookshelves! Real wood, no more plastic. I feel like such a grown-up.” The bookcase was bolted into the wall, baby-safe already, and Eric had left the bottom three shelves empty, perfect for the baby’s books and toys.

“There’s no art. You can put up some of your things. I always liked that big coffee cup.”

Lacey looked at the blank wall between the two big windows, and her mind flashed to the same wall in Harry Rakoczy’s house next door: his sister, Dora, charcoal under glass, her face tilted against the violin, her long wild hair.

She loved the furniture, but what had Eric done? He’d been counting pennies ever since her last day of school; he’d lost his temper over fifty dollars to keep the moving van overnight, twenty dollars to replace the dishes, and now this? “Are you sure?” she said.

She wanted the furniture. It was everything she wanted: a houseful of things that couldn’t be packed up and moved overnight, a home with weight, an anchor for her life. This was the home she’d drawn in her school notebooks, all those nomadic years with her mother. These beautiful rooms. Eric knew what she wanted; but she knew what he needed. She tried again, knowing she had to voice her doubt as a true question; she had to give him the chance to change his mind.

“Are you sure we can afford this?” she said. “If it’s too much, we could wait.”

“There’s no interest for six months. Don’t you like it?”

He sounded disappointed, and of course she liked it—he always knew what she liked. It would have been fun, though, to have chosen the furniture herself, to have hunted through the store with Eric. An ungrateful thought, and she pushed it away: in the end she would have picked precisely this. “I love it,” she said. The bookcases stood on either side of the fireplace, and there were all the books and CDs, along with his grandmother’s Ukrainian Easter eggs in Waterford crystal eggcups. All that work. She knew, without asking, that he had unpacked every box except those marked Lacey Classroom, flattened the boxes, and tied them in a stack in the garage. And the Classroom boxes were up in the attic, and when she opened them a year from now, maybe two, they would smell of crayons and the future. “And you unpacked all this,” she said, sighing. “I worried about it all night.”

“Come see the bedroom.”

Lacey grabbed Eric’s hand, ignoring the pain that shot across her palm. “How did you do this? All in one night?”

“You don’t get through law school by sleeping. Come and see.”

Eager to see and approve the bedroom, she pulled him to the foot of the stairs. They were finished with the same deep-amber oak flooring as the rest of the downstairs, with a runner of red carpet coming down, held in place by brass rods on each step. That was so typical of Eric, the exact detail, his concern that she might slip on the glassy wood. In the kitchen, she knew, he had already replaced the broken window.

She sensed something—not a sound, but an approach—and she looked up the stairs. Something dark rushed down, something too dense and hectic to see. Blackness seized her by the knees. It hit her all at once, driving into her breastbone. She coughed and pulled for air, and her lungs resisted, unwilling to open again. To breathe felt like an effort against life, as if she had to open her mouth underwater.