Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: BoD - Books on Demand

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

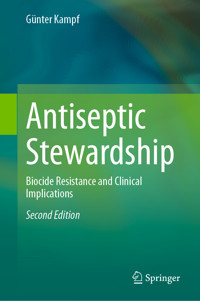

- Sprache: Englisch

A letter to the editor published in The Lancet in November 2021 about the unjustified stigmatisation of people without COVID-19 vaccination attracted international attention (top 5% of all articles). But it also led to unexpected reactions from citizens, doctors and scientists to the author: 88 emails, two rebuttals in The Lancet and an attempt of pre-emptive censorship by a university representative. The emails expressed gratitude for the letter and great concern about social coexistence after the pandemic, illustrating how not only courage but also humanity unfold in the face of an insecure and increasingly divided society. During a pandemic we are all ultimately part of the same human community, regardless of our vaccination status. With a foreword by Martin Kulldorff, former professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, this is a timely document that not only enlightens, but also inspires reflection and calls for action.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 68

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Foreword

To stigmatize people for health reasons has a long and ugly history. The Bible mentions how lepers were shunned by society, teaching us instead to show compassion and care. More recently, homosexual men with HIV/AIDS were stigmatized in the United States and around the world. An important principle of public health is that we care for everyone in a compassionate manner, irrespective of their health status or behavior. While public health should encourage people to stop smoking, we do not stigmatize them as being bad people and we do not deny them health care if they develop lung cancer. While we encourage healthy eating and exercise, we do not shame obese people or fire them from their work.

Among public health professionals, there used to be consensus that it was both unethical and counterproductive to stigmatize people, and most of the public agreed. That is, until the Covid pandemic threw this consensus out the window. When someone caught a Covid infection, they were often blamed for not being careful enough, not wearing a mask, for not socially distancing, for breaking lockdown rules or for not being vaccinated. This led in turn to social media posts where those with a recent Covid infection desperately tried to ensure their friends and followers that yes, they had taken all the required Covid precautions but got sick anyway.

Disturbed by all the stigma around Covid, in 2021 I posted the following on Twitter: ‘For thousands of years, disease pathogens have spread from person to person. Never before have carriers been blamed for infecting the next sick person. That is a very dangerous ideology.’ It got 14 million views and 9,400 comments. The second sentence is obviously untrue, and people jumped on it to point out that they were not the first ones to blame the sick. A few colleagues were more astute. Michael Senger tweeted that “In a strange twist, blue-check Twitter mobbed @MartinKulldorff's tweet yesterday with tons of horrifying examples of infected persons being blamed, shamed, and ostracized in history—using those examples, bizarrely, to justify their own blaming of those infected with COVID.” Francois Balloux commented that my tweet was ‘either a complete brain fart or one of the most sophisticated examples of Socratic discourse. Whatever the intent, it got many to reflect on the abuse the most marginalised people in society experience during times of moral crisis. As such, it did its job.’

The stigmatizing of the sick eventually stopped. Not because of my tweet, but because almost everyone eventually got Covid, no matter what precautions they took. People don’t like blaming themselves, and how can you blame others for getting sick if you have also been sick?

One type of stigmatization was especially severe during the pandemic, and it has not yet ended. That is the stigmatization of the unvaccinated. Like the lepers in biblical times, the unvaccinated were shunned from society, not allowed to go to college, visit restaurants, attend cultural events, and in many cases, fired from their work. Putting aside the cruel and ugly aspects of this, it was also unscientific. The Covid vaccine trials had not shown that the vaccine would reduce transmission, and with a vaccine it can go either way. If the vaccine reduces symptomatic disease, infected persons may be more likely to spread it to others if they are vaccinated, as they will be out and about meeting other people, while unvaccinated people with symptoms stay at home in bed. Moreover, people who had recovered from a Covid infection already had natural immunity that was superior to the vaccinated, and with millions of unvaccinated high-risk people around the world due to vaccine shortage, it was unethical to vaccinate them. The same is true for young adults who were at miniscule risk of dying from Covid. Rather than stigmatizing them for not taking the vaccine, they should have been applauded for allowing older high-risk people to get the vaccine instead of them.

There were some attempts to counter the stigmatization of the unvaccinated. In The Lancet, Professor Günter Kampf published an important and well written piece, arguing that ‘stigmatizing the unvaccinated is not justified’ and that it was inappropriate to use the term ‘pandemic of the unvaccinated’. This piece that should have been indisputable to everyone, turned out to be controversial, receiving an enormous amount of attention.

In this book, Dr. Kampf outlines some of the many reactions. In the past, stigmatizations often came from politicians, the media and segments of the public, with scientists and public health officials patiently and valiantly trying to counter it, knowing how unethical and counter-productive it is for public health. With the Covid vaccines, it was the other way around. It was public health officials and academics who were in the driving seat, pushing a destructive narrative that politicians, the media and some members of the public picked up on. That is a shocking and disturbing aspect of this stigmatization of the unvaccinated, and it will not go down well when the history of the Covid pandemic is written.

The positive aspect is that many people did not go along with it. This book is a beautiful testament to that. It is wonderful to read the many thoughtful and humane responses that Dr. Kampf received to his Lancet publication. It fills one with warmth and hope for the future.

Martin Kulldorff

Table of contents

Background

The Lancet Letter

Overview on reactions

Reactions from citizens

Reactions from physicians

Reactions from professors

Reactions from scientists

Reactions from students

Reactions from psychologists

Reactions from nurses

Other reactions

The reaction from my university

Two reactions published in the Lancet

Tolerance

14.1. Tolerance in science

14.2. Tolerance in the society

References

About the author

1. Background

The year 2021 was marked by the COVID-19 pandemic, not only in Germany. Probably the most moralised issue during the pandemic was the vaccination status. The moralising phrase ‘pandemic of the unvaccinated’ was coined early in the pandemic and quickly caught on. The idea that the pandemic had become more or less exclusively the domain of the unvaccinated has been persistent [1]. It was a time when politicians repeatedly made public statements about the dangers of unvaccinated people. Here are some examples.

Joe Biden, President, USA

“Look, the only pandemic we have is among the unvaccinated.”

(17 July 2021; AP News)

Janosch Dahmen, Green Party, Germany (translated)

“Restrictive measures can only be justified if a group of people poses a danger. Vaccinated people are no longer a danger, so restrictions can no longer be applied to them.”

(26 July 2021; ntv)

Markus Söder, CSU, Germany (translated)

“Anyone who has been vaccinated is not a danger, which is why their fundamental constitutional rights must be restored.”

(10 August 2021; BR, Bayerischer Rundfunk)

Jennifer Russell, Chief Medical Officer, Canada

“This is a pandemic of the unvaccinated.”

(2 September 2021; Toronto Star)

Jens Spahn, CDU, Germany (translated)

“We are currently seeing a pandemic of the unvaccinated.”

(8 September 2021; DW, Deutsche Welle)

The public perception was clear: only the unvaccinated population was part of the pandemic, and only the unvaccinated population was able to transmit SARS-CoV-2 to contact persons so that the driver of the pandemic was the unvaccinated population. Very clear. They were to blame for the continuation of the pandemic. It was therefore only fair to impose restrictions on their public life, such as the 2G contact restrictions in Germany [2]. But was it that simple?

There was growing evidence that the vaccinated population was also infected and capable to transmit SARS-CoV-2 to contacts. Initially, it may have been true that the vaccinated were less likely to be infected and therefore less likely to be a possible source of transmission. But the black-and-white picture painted by some politicians was certainly wrong. And in October 2022, the protocols of the Robert Koch Institute even stated that there was no evidence that vaccinations make any difference to excretions [3].