Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Fantasy und Science-Fiction

- Serie: Folk Tales

- Sprache: Englisch

'Delightfully offbeat and always engaging, this collection of folk tales offers new perspectives on both familiar and forgotten stories. Perfect for folklore fans and anyone who wants to add a bit of magic to their day.' - Heather Fawcett, Sunday Times best-selling author of Emily Wilde's Encyclopaedia of Faeries Do you know the legends of the giants who ruled England before the first human kings? What about the demon dog Black Shuck who terrorized sixteenth-century Norfolk? Or the many times the Devil has tried to get his way before being outwitted by everyday people? England's historic counties are overflowing with folklore, and this collection of 39 stories from the hit podcast Three Ravens reimagines dozens of classic tales in surprising, spooky, and often hilarious ways. Filled with tales of ghosts, mermaids, half-forgotten heroes, bloody legends and more, The Three Ravens Folk Tales spans centuries, styles, tones and narrators, making it perfect for bedtimes, reading by torchlight, or curling up on the sofa to enjoy with a mug of something hot.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 600

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2025

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

First published 2025

The History Press

97 St George’s Place, Cheltenham,

Gloucestershire, GL50 3QB

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

Text © Eleanor Conlon & Martin Vaux, 2025

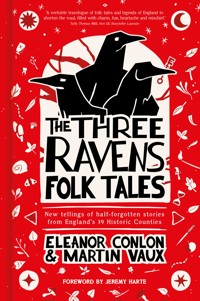

Illustrations and cover design © Olly James-Dare

The right of Eleanor Conlon & Martin Vaux to be identified as the Authors of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 80399 969 2

Typesetting and origination by The History Press

Printed and bound in Great Britain by TJ Books, Padstow, Cornwall.

eBook converted by Geethik Technologies

The History Press proudly supports

www.treesforlife.org.uk

EU Authorised Representative: Easy Access System Europe

Mustamäe tee 50, 10621 Tallinn, Estonia

For storytellers everywhere, whether big or small, hairy or scaly, real or imagined, and all things in between.

Contents

Foreword

Introduction

1. Bedfordshire: The Bottled Curse

2. Berkshire: Herne the Hunter

3. Buckinghamshire: A Promise Kept

4. Cambridgeshire: Hereward the Wake

5. Cheshire: The Bells of Rostherne Mere

6. Cornwall: The Mermaid of Zennor

7. County Durham: The Sockburn Worm

8. Cumberland: Long Meg and Her Daughters

9. Derbyshire: The Boggarts of Arbor Low

10. Devon: The Hairy Hands of Dartmoor

11. Dorset: William Doggett, the Vampire Ghost

12. Essex: Three Knots

13. Gloucestershire: The Torbarrow Guardian

14. Hampshire: The Netley Abbey Phantoms

15. Herefordshire: The Dragon of Mordiford

16. Hertfordshire: The Blind Fiddler of Anstey

17. Huntingdonshire: The Lantern Men

18. Kent: The Queen of Bones

19. Lancashire: The Cockerham Devil

20. Leicestershire: Black Annis

21. Lincolnshire: The Tiddy Mun of Ancholme Vale

22. Middlesex: Brutus of Troy and the Giant Gogmagog

23. Norfolk: Black Shuck

24. Northamptonshire: Dionysia, the Female Knight

25. Northumberland: The Fish and the Ring

26. Nottinghamshire: Buttermilk Jack and the Blidworth Witch

27. Oxfordshire: Lord Lovell’s Bride

28. Rutland: Four Eggs a Penny

29. Shropshire: The Legend of a Cat, and by your allowance, his Earnest Friend Richard, Latterly of Whittington

30. Somerset: The Restless Witch of Sandhill

31. Staffordshire: The Children of Cannock Chase

32. Suffolk: The Wild Man of Orford

33. Surrey: The Tale of Blanche Heriot

34. Sussex: Cuthman of Steyning and the Devil

35. Warwickshire: The Legend of Guy of Warwick

36. Westmoreland: The Witch of Westmoreland

37. Wiltshire: A Cuckoo in Winter

38. Worcestershire: The Legend of the Swan

39. Yorkshire: The Discovery of Supposed Witchcraft

Foreword

By Jeremy Harte

There are many ways to tell a story. Start with ‘A man walks into a bar’ and your audience knows exactly what they’ll get – strong plot, straightforward character, and no frilly stuff with atmosphere or scene-setting. A lot of English folk narrative is like that, or at least that’s how it feels when you read the great county collections. Of course, some of the plain speaking may be accidental. When Victorian folklorists walked into bars, they weren’t armed with a smartphone to interview the old fellow in the chimney seat, and there is only so much of a story that you can carry in your head from a single telling, even for a generation that had grown up memorising Latin verse and the Collect on Sundays.

When you read the oldest transcripts of English tradition, their style is usually terse. It’s a pity, but then we are lucky to have the stories at all. There’s never been a time when everyone was above average, and collectors were lucky to find an informant who could remember what happened and when, let alone pace the funny bits and add an occasional touch of pathos. That wouldn’t matter if we could go back to the original storytellers, armed with proper recording equipment: but those days are gone. The canon of local legend in England has been closed now for a good hundred years. Folklore continues to thrive, twining through our lives and institutions like ivy in a thicket, but the specific folk genre of the local legendary tale came to an end not long after the last soldier returned from the Great War.

But that end was also a beginning, for the one constant in tradition is change. As Heraclitus so nearly put it, a man cannot step into the same bar twice. By the time it had become clear that no more new tales (or songs, or dances, or curious customs) were going to be garnered from elderly rustics – or whoever else counted as ‘the folk’ – a new living tradition of performance was already in place, folk in its style if not its lineage. The twilight days between the old native informant and the new craft storyteller were marked, as twilights so often are, by shadows and false outlines. Many excellent raconteurs gained a hearing by pretending to pass on something orally inherited when in fact they were putting spin on a piece they’d read or invented from the folk idiom. What mattered was re-establishing live narrative performance as an art on a par with music or dance or drama.

Good stories are many, while good storytellers are few. Eleanor and Martin are two of the best. The Three Ravens (I know there are only two of them, but this is an English tradition, right?) bring a questing intelligence to the great collections of lore and their stories are just as much fun whether you are hearing them for the first time or whether you’re an obsessive who’s been tracking Herne the Hunter since he first rode out. Local legend is a very loose category, a rummage bin into which past generations have thrown the third division of medieval heroes, old landmarks newly explained, and proofs of the supernatural which entertain more than they convince. It is so grounded in the real that it provokes the imagination: wave the wand of story and our familiar hill is revealed as the coils of a dragon. And there is no better way to hold an audience than local allusion. Why send a man into a pub when he can walk into the Admiral Benbow, the Prancing Pony or the Moon Under Water?

This is the appeal of legend, its combination of somewhere that could be nowhere else – the Downs, the Peak, the Fens – with narratives that have been floating around the world free as thistledown for the last few thousand years. These stories tangle up with each other, like a kitten’s knitting. Until you begin to tell them, you cannot say what motif will bring in another, pulled by some magnetic attraction. Often in this collection the Ravens will begin with one canonical story and another will insist on being told as a prequel or sequel. That is a time-honoured practice: how do you think the Bible was built up, or the tale of Troy?

Old-style storytelling was not just terse, it was chronologically flattened. Everything happened in the indeterminate zone of once upon a time: sort of medieval (it has knights, dragons and castles) but modern at the same time. I suppose that tradition began when medieval was modern. To the credit of the Ravens, they have found new settings for old tales, from the contemporary memoir to the eighteenth-century found document, and tell them in different voices, from dialogue to first-person to the most challenging of all, a story told from the perspective of the supernatural.

Turn from one tale to another and appreciate their chameleon changes in style, presentation and atmosphere. The modern performative story is a sturdy hybrid between two stocks: traditional oral narrative and a modern literary sensibility. From one it derives plot, location and the aura of expectation that clothes ‘king’, ‘gold’ and ‘witch’; from the other it has learnt to ask what people feel, and why. Suddenly weary of the din in the crowded streets, the man turned with a shrug through the first door that presented itself, and found himself alone in a cool, dusty mahogany-lined bar.

Literature has taught us to ask questions never contemplated in the original tale-types. In traditional narrative, Jack returns from his travels with golden coins, a noble horse and a princess: any princess will do, they are as interchangeable as the coins and have as little choice as the horse. There is a bright innocent egotism about this kind of tale which suits the world of childhood, but we are telling for adults. With unobtrusive art, the Ravens give the actors in their stories an inner life. What does a mermaid expect out of marriage? How does it feel when other people call you a witch?

They say stories are universal but this isn’t true. A straight delivery from the Golden Legend, that great medieval collection of saints’ lives which fixed ‘legend’ as the word for our particular genre of story, leaves a modern audience deeply uncomfortable. Its blood libel stories, like Little St. Hugh of Lincoln, can be read in the study but they cannot be told or sung. There is a moral complicity about live storytelling, though that doesn’t exclude acts of violence – at least, not yet. The body count in traditional narrative would make a police procedural blush and this goes back to the first singers of epic, when a man rode into a mead-hall and burnt it down with everyone inside.

Three thousand years after the Iliad, songs of battle still have the power to thrill rather than shock. We are less violent than our ancestors but we will die just like them, which is why the ghost flits through traditional story, a reminder that while we know so much more than previous generations, we are as ignorant about the one inescapable thing. The Ravens have a fine spectrum of ghosts – grim, wicked, sad, even misunderstood. For things are not always as they seem and even monsters have their good points. Inside every fire-breathing dragon lies the pet it once was, and the crooked figure bending over a still body may be a healer, not a witch. A good story has the power to make us think about buried things; we absorb them as children but return to explore them as adults. We may have given up guarding our houses against sorcerers and fiends with mark and spell, but they are still there inside us and the only protective magic is wisdom and compassion.

The Ravens are wise birds but they are also evocative, stylish, dramatic and frequently hilarious. Don’t let me keep you outside any longer. Walk in and they will serve you.

Jeremy Harte

2025

Introduction

Gather round the campfire and listen in…

It was Isaac Newton who, in writing to Robert Hooke in 1675, famously said, ‘If I have seen further it is by standing on the shoulders of Giants’. In this, Newton, like many grand people, proved himself to be a dreadful liar. He never stood on the shoulders of a single giant, as far as anyone can tell, even though England is absolutely littered with them. Some are sleeping, some are dead, and some are very wisely keeping their heads down…

To us, the kinds of giants who have helped us see further are writers. Be they chroniclers, historians, traditional storytellers, novelists, short story writers, or any other noble spinner of tangled yarns – since we were both children, we have gobbled up stories in a manner many would find outright greedy and quite unpleasant to watch. To name them all would fill a book in itself. Still, our love of folk tales and old stories, many of which we’ve retold in all sorts of ways over the years, prompted us to launch our podcast, Three Ravens, in March 2023, and share our passion for them.

When we embarked on the project, we hoped we might find a listener or two who would be interested in the same tales we were. Tales of ghosts, monsters, heroes, and mermaids, the odd urban legend, and even odder true stories, some of which are scary, some of which are funny, and some of which are just downright strange.

Little did we expect quite so many people to join us every week, and as Three Ravens has grown and grown, we have been overjoyed to discover that the world is positively teeming with people eager to hear our tellings. But it’s important to remember, the stories were there before us, and will be there after we’re gone, too.

Rather than ravens, we have been a bit more like magpies, picking up shiny and interesting tales as told by others then rewriting them to pass on, in the same way people have been doing since giants weren’t so shy and dragons were plentiful, and many ghosts were still living people all going about their business. Nonetheless, passing these stories on to you has provided us with a huge amount of joy and, likewise, the thousands of other people around the world who have downloaded episodes of the podcast, and the many who have shared their favourite stories with us. Although, we do all now have a responsibility to keep telling these tales in our own ways, whether at bedtimes, or around pub tables, or in paintings, songs, or other styles in which you feel they ought to be shared. Some might make a nice hat, for example.

As for our tellings, they are all designed to be read aloud to others, ideally with silly voices, but you can just as well read them silently in your head. And if there are bits you don’t like about them, do feel you can change them and make them better, because stories are at their best when the teller twists them to make them fit into an odd-shaped hole in their day. That way, they can be keys and unlock passages through to special places. Like the past. Or the world of the fairies. Or that achey bit inside you, just above your tummy, where love lives.

In fact, for us, this collection of tales is a love letter to England. Each of the nation’s thirty-nine counties is bristling with half-forgotten strangenesses, crumbling castles, and layers of mystery waiting for people to dig down into to find stories buried in the earth. Each of these stories was written during just our first lap of wandering, listening, digging, and learning, and since then we have written more, with much muddier fingers.

So, although not every tale here is perhaps the most famous a given county might have to offer, to us each one is a special treasure: the shiny thing we unearthed and polished up to share. As such, we hope you enjoy the ways they all shimmer and shine. And if you find yourself, for whatever reason, stood on a giant’s shoulder, do consider passing these tales on to the people below. Who knows what they might do with them, but knowing people, it will probably be something really interesting.

In the meantime, though, we’ll get out of the way and let the stories speak for themselves.

And remember, don’t whistle until you’re out of the woods…

With love,

Eleanor & Martin

1

The Bottled Curse

A Bedfordshire Tale

Over 200 ‘witch bottles’ have been discovered in Britain, buried in the ground, tucked up chimneys and bricked into walls. Witch bottles are associated with apotropaic magic and often contain pins, hair, nail clippings, and other viscera, fabric, and small personal items. The majority date from the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries.

I had been interested in the idea since researching witch bottles and bellarmines, and I wanted to bring into this story the folk belief that the spirit of a malicious practitioner of magic could be trapped within a bottle. However, the tale of Sally, the witch of Dunstable, was not an ancient Bedfordshire folk tale at all. It was invented by the headmaster of the local school in 1875. His name was Mr Wire, and he was apparently attempting to shame the vicar into tidying up the churchyard. Wire was so taken with the idea that he wrote an eighty-one-verse poem about it. The poem was incredibly popular but put an end to his career as headmaster.

I also wanted to tie in the local legend about Five Knolls, the barrow graves on Dunstable Downs. It was thought to be a supernatural place, where the Devil might appear to witches in the form of a cat.

EC

For most of us, chaos is a negative thing, an absence of law and order. But there are some who consider chaos to be a gift, a state from which creative thought can grow.

One such person was a witch named Sally, who lived a great many years ago in the town of Dunstable. Sally thrived on mess and disorder, and her ramshackle cottage was always in a complete state of disarray. There were piles of books and papers which threatened to cascade over and crush unsuspecting visitors. There were half-eaten cakes mouldering on platters and mouldy cheeses providing a feast for the mice. There were sticky rinds in the basins and bathtubs, and the windows were so filthy that Sally could barely see out.

She was a great collector of all sorts of things, from birds’ feathers to fancy hats, copper pots to patty pans, and she liked nothing more than to have everything she had ever collected all around her, all at once. She also had a habit of picking up new hobbies all the time and not continuing with them, so a trail of evidence of her interests was scattered all around her. There was knitting in the bedrooms and painting up the stairs, and a full half of Sally’s kitchen was devoted to a set-up she had devised for brewing her own beer.

I’ve mentioned that Sally was a witch, and she was actually quite a good one, although the mess in her house meant it was sometimes difficult for her to lay her hands on exactly the right ingredients for a love potion or a good luck charm. It was quite common for anybody who needed her services to have to wait for a good long while, trying not to drink the sweet tea offered to them in a dirty cup, while Sally rummaged around in cupboards which spilled their contents onto the floor, her frizzy grey hair flying everywhere, and eventually located the thing she was looking for in an unlikely place, like the coal scuttle or under the lid of the harpsichord. Nobody knew how Sally had got her hands on a harpsichord, but whenever she played it, her long ragged nails scraping against the yellowing keys, they soon knew that it was extremely out of tune.

Despite her eccentricities, Sally did manage to help the people of Dunstable with their little problems, so they kept coming to visit her. There was nobody like Sally for brewing teas to get rid of unwanted boils, babies, or birthmarks, or turning thorns and scraps of ribbon into amulets. She was good for a gossip, too, and most people left her house feeling satisfied with their visit, if slightly in need of a full body wash.

Sally did have one enemy in Dunstable, though. The local vicar, Mr Pascoe, disliked everything about the scatter-brained witch. He was a man who favoured order and cleanliness, and he was often to be seen polishing the church door knobs or straightening the chalice for Holy Communion. Sally and her lifestyle, not to mention her magical proclivities, went against everything Mr Pascoe believed in.

If Sally was quite a good witch, then Mr Pascoe was quite a good vicar. He took his job seriously and never lost an opportunity to spread the word of God to those he felt most needed it. And so, he forced himself to make monthly pilgrimages to see Sally, even though he hated being in her scruffy, cluttered house.

‘Now look, Sally,’ Mr Pascoe said, as he hovered nervously in the kitchen, not wanting to sit down on anything in case it stuck to his cassock. ‘You really have got to come to church, you know. You’ve lived here for sixty years and more, and as far as anybody knows you’ve never been. The Queen doesn’t like that sort of thing, and I have to report to the diocesan authorities. Won’t you come this Sunday?’

‘No, thank you, vicar,’ said Sally, who was pottering about, absentmindedly stirring some evil-smelling liquid in a large pot, which she had vaguely claimed was rat poison. ‘I’m far too busy.’

The vicar made his usual protests about being busy on a Sunday being a sin in the eyes of the Lord, but Sally wasn’t really listening to him. He valiantly persisted, but Sally started loudly singing a rather rude ballad. It was difficult for the vicar not to hear some of the words, although he wasn’t sure he actually understood all of them.

‘Look, Sally,’ he said at last, becoming very cross when Sally opened a cupboard and a small flock of blackbirds flew out and disturbed his carefully placed hat, ‘you should address yourself to your immortal soul, and to this horrendous mess of a house. It’s a shameful thing! Cleanliness is next to godliness, you know.’

Sally stopped singing, and her hand stilled as she stirred the pot.

‘Are you calling my house messy, vicar?’ she asked softly, in a tone which would have caused most people to take a step back.

‘Well, it is,’ said Mr Pascoe staunchly, in spite of the way Sally raised her copper ladle. Several drops of rat poison dripped from it on the floor and hissed where they fell.

‘How dare you,’ said Sally, who didn’t consider her house to be disordered at all. ‘Get out, and don’t come back!’ And she shook the ladle at him so ferociously that the vicar turned and fled, telling himself he had done his duty for another month.

Although Sally liked the way she lived, the vicar’s words had upset her deeply. She thought about them all day, and the more she thought, the angrier she became. Hadn’t she been doing her best to help the people of Dunstable, giving them exactly what they wanted and needed and never asking for any payment? She was doing a damn sight better than that pompous ass of a vicar. What did he ever do, except mutter prayers and obsessively tidy things up? It was unnatural, sweeping and scrubbing as much as he did, Sally thought. Somebody ought to teach him a lesson.

The more she thought about this idea, the more she became convinced that the person to teach the vicar a lesson was surely her.

Now, Sally had never been particularly malicious, but a person can be pushed too far. However, she knew that her skill with herbs and charms probably wasn’t going to be enough to seriously inconvenience the vicar. She was going to need more power.

And so, at the next full moon, Sally put on one of her fancy hats and walked down to the Five Knolls, where it’s said the ancient kings sleep. She made her way to the three bell-shaped barrows in the middle and she ran around them nine times widdershins. Then, rather out of puff, because she was pushing seventy-five years old, she squatted down and traced a magic circle in the soil.

No sooner had Sally closed the circle than out shot the Devil himself in a pillar of bright blue flame, whooping and cheering to be let loose out of Hell.

‘Good evening, Devil,’ said Sally politely, doffing her fancy hat. They had met before, of course, but it had been some time ago, when she had been a much younger woman. She hoped the Devil would still recognise her, especially with her clothes on.

‘Hello, Sally,’ said the Devil. To a being as ancient as he, Sally still looked exactly the same as the pretty young woman with a bird’s nest of frizzy hair who had summoned him all those years ago. ‘What brings you to summon me this fine moonlit night?’

‘Well, Devil, I haven’t asked much of you for all these years,’ Sally said, ‘but there’s a small matter of a troublesome priest.’

‘There usually is, sooner or later,’ the Devil said, nodding wisely.

‘In short, I need a bit of extra help,’ said Sally.

‘Not a problem,’ said the Devil, who could be very helpful when he wanted to be. He felt a degree of fondness for Sally, as she often left him gifts of mummified cats and bottles of brandy, and in truth, he had a very similar attitude to mess and chaos, so they were well suited. ‘I’ll give you the power to make anybody who crosses you regret it.’

‘Wonderful,’ said Sally. ‘I knew I could count on you.’ And she shook hands with the Devil, thinking of all the ways she was going to make Mr Pascoe pay for insulting her. Blue flame shot from their clasped hands, and it flew so high that the few folk of Dunstable who were still awake at that hour mistook it for a shooting star.

Sally adjusted her fancy hat and started to make for home, but the Devil followed behind her.

‘What are you doing?’ asked Sally. ‘Have you business in Dunstable, Devil?’

‘I’m coming with you, of course,’ said the Devil. ‘I told you I would help, so here I am.’

‘Hold your horses,’ said Sally. ‘You can’t come with me looking like that. The priest already doesn’t like me – he’ll cause no end of a to-do if he sees you.’

The Devil looked down at his hairy goat legs and concluded that she was probably correct.

‘Besides,’ Sally said. ‘The spare bed’s got knitting on it, so there’s nowhere for you to sleep.’

‘That’s not a problem,’ said the Devil. ‘I can curl up in the fireplace with the coals.’

‘I don’t think so,’ said Sally. ‘The postman always likes to sit by the fire when he comes, and I think he would be distressed to see you in there. Can’t you do something about all – this?’ she waved her hand, generally indicating the Devil’s entire appearance.

‘Oh, alright,’ said the Devil, and in a shower of glittering blue sparks, he shrank himself down, yowling horribly all the while, until he was in the shape of a fat, shaggy tortoiseshell cat with glowing green eyes.

‘Perfect,’ said Sally, scooping up the cat and carrying it home with her.

From that day on, Sally and the Devil disguised as a cat were completely inseparable. Sally fed the cat bowls of milk with drops of fresh blood stirred into them and the cat slept on her chest at night and whispered things into her heart.

People who came to visit Sally began to notice a difference about her. Where before she had been good-natured, if a little scatty, she started to be irritable and say spiteful things. And her temper! Oh, it was fierce! If she suspected the slightest insult, she would lash out at the person responsible for it.

And strange things started to happen, too, whenever anybody crossed her.

The blacksmith asked for a love charm, but he didn’t pay Sally quickly enough, so instead of becoming irresistible to the object of his desire, his face sprouted ugly, oozing pustules that Sally refused to help him remove.

The miller’s wife asked for an elixir to help her have children, but she gossiped about Sally behind her back and called her a smelly old woman. News of it got back to Sally, and soon the miller’s wife found herself giving birth to four goats instead of human children.

Word started to spread through Dunstable that Sally was a force to be feared, and when Mr Pascoe heard about it, he decided that enough was enough.

‘Listen, Sally,’ he said. ‘I’ve been very patient with you for all these years, but you’re causing real trouble now. If you don’t stop at once, I’ll have no choice but to call in the witchfinder.’

‘You just try it,’ Sally said, and the ends of her hair seemed to crackle with rage. She pointed a finger at Mr Pascoe, and behind her the tortoiseshell cat reared up on its hind legs and hissed and spat, and for just a moment Mr Pascoe could see the Devil there, as plain as the nose on his face.

But Mr Pascoe was determined, and despite his fussy ways he had courage enough. He summoned the witchfinder, who made his way up Sally’s treacherous garden path and arrested her.

There was a trial, but it didn’t take long, because it turned out that there was quite a lot of evidence against Sally, what with the goats and the pustules and all the other inconveniences.

Funnily enough, the tortoiseshell cat was nowhere to be seen. It had vanished into thin air the day Sally was arrested. I can only assume that the Devil had concluded that Sally’s soul would be with him in his homeland soon and had gone back to make things good and warm for her.

Things were warm enough for her in Dunstable, for those were the days when witches were burned at the stake. The whole town turned out to see Sally, who was still spitting feathers with rage even as they lit the pile of wood below her. Mr Pascoe turned pale as she started to smoke, for she screamed a loud curse, vowing her revenge on the people of Dunstable and most especially the vicar. He was very relieved when Sally had been reduced to a pile of ash and went home thinking himself lucky that his troubles with her were finished.

Unfortunately, his relief didn’t last long.

Strange things started to happen in the vicar’s house and in the church. During Holy Communion, the chalice was suddenly lifted from Mr Pascoe’s hands and the wine was tipped all over his head. The chafer dish was tossed from one end of the church to the other, scattering Communion wafers like falling snow. Hymn books were carried up to the rafters and dropped down in handfuls of pages, and foul smells wafted through the pews, making the congregation gag and cover their mouths.

After one particularly bad Sunday morning, Mr Pascoe was standing in the mess of his church, and he knew that it must be Sally’s spirit exacting her revenge. Ever a proactive person, Mr Pascoe immediately wrote to the witchfinder, who wrote to his friend the exorcist.

The exorcist came down to Dunstable at once with his bag of equipment and Mr Pascoe watched as he solemnly conducted his ceremonies of candle, book and bell. Sally’s spirit put up a good fight, but eventually the exorcist was able to annoy her into manifesting in the back corner of the church, near the font.

Mr Pascoe had a brief sighting of the furious ghost, its eyes blazing, smoke pouring from its ears, before the exorcist harnessed it and stuffed it into a bottle, which he hastily sealed with four layers of thick black candle wax.

‘There you are,’ said the exorcist, handing Mr Pascoe the bottled spirit, along with an extremely large bill.

Mr Pascoe didn’t quite know what to do with Sally’s spirit, but everybody advised him to bury the bottle deep in the grounds of the church to prevent Sally from ever rising again to cause trouble. So, that’s exactly what he did, and he said any number of prayers over the site of its burial. He felt a little bit guilty, too, so he did say some prayers for Sally’s immortal soul as well.

Although Sally’s spirit never directly troubled Mr Pascoe again, that still wasn’t quite the end of it. Slowly but surely, the churchyard started to show the effects of her influence. The fences fell down and the gravestones cracked. Poison ivy wound itself around the trees and crept over the ground. The grass grew long, concealing holes which liked nothing more than to twist people’s ankles. The bones of the deceased began to poke up above the surface of the earth.

In short, the churchyard was soon just as much of a mess as the home of Sally, the Dunstable witch. But Mr Pascoe refused to dig up the spirit’s bottle, for fear that Sally would get out again and terrorise him, and so the churchyard remains in a terrible state, getting worse with each passing year.

Perhaps one day a future vicar may tidy it up, and perhaps they may find a small, dirty bottle sealed with four layers of thick, black wax, and perhaps then Sally’s spirit will roam free, causing chaos wherever she goes.

2

Herne the Hunter

A Berkshire Tale

A famous figure of English folklore, Herne the Hunter is mentioned by Shakespeare in The Merry Wives of Windsor and in several other places, too. He is one of many ghostly wild huntsmen who haunt the nation’s landscapes, sometimes with packs of dogs, including the likes of ‘Old Crockern’ in Devon, ‘Gabriel’s Ratchets’ in Derbyshire and the North of England, and ‘Eadric the Wild’ in Shropshire and Hereford.

Our first recorded Wild Hunt story comes to us from twelfth-century writer, Walter Map, in his De Nugis Curialium (‘Of the Trifles of Courtiers’), where the tale is of King Herla and set in Cambridgeshire. So the story goes, Herla rode into the Otherworld of the faeries and then out again, though once he had returned 300 years had passed.

As for Herne specifically, he has stag’s antlers and was – and still is – famously associated with an oak tree in Windsor Great Park. This tree has been felled and replanted several times and is held as significant to monarchs including Queen Victoria.

That the ‘original’ ancient Herne’s Oak was felled during the reign of George III felt like too good a detail. After all, George III went mad, and it was under his reign that England lost the American War of Independence. This felt somehow significant. Hence my placing of this story in the mouth of Dr Robert Darling Willis, a real historical figure who had a complex personal life and treated the king alongside his father, Francis.

MV

Dearest Mary, how I crave to see you.

The shocks I have had to my heart and to my mind are the stuff from which some men never recover. Were it not for your love of me, I too may have lost grasp of my senses, as has he. But he is not mad, Mary. It is not what I thought. I have seen with my own eyes the truth of it. Our most noble king is no lunatic. Rather, he is haunted by a fiend most ancient and abhorred, afflicted with a curse I fear may never be lifted.

As you know, my father was the first in our family called to serve the king. That was in the year 1788, when I was still in pursuit of my fellowship at Gonville & Caius College. I was, at this time, intermittently employed as a physic in Grantham, working alongside my brother, John. He, being older, accompanied our father down from Lincolnshire to London, and there repaired to the White House at Kew Gardens under the strictest conditions of secrecy.

You know, my love, that the Willis family are not from an ancient or noble line and our fame and wealth, such as it is, is a direct result of the efforts of John and my father in the treatment of our king. For all the kingdom knew of the madness of King George III – nay, all the world knew of it – and so, those men who by their skill cured him of it, well, the world was open to them like a pearl revealed within an oyster.

I was at that time but twenty-eight years old, a decade from meeting you that fine summer’s day. And now I know you are at home in Buckingham Street, with our angel Robert no doubt babbling on your lap. It is of great shame to me that I cannot be with you, and my heart burns to know the ignominy heaped upon men such as I, who wed though forbidden to do so.

As a Cambridge Fellow, I have duties to perform, and no greater duty than this which I have undertaken to do, and so we must remain apart and our love a secret. But I had always believed that once the king was well again, I could return to my duties as a father and as your beloved.

Alas! For what I have seen tonight chills me to the core and gives me the fear that I should never be able to return to your side, for our king’s malaise is not of the mind but of the body politic.

Yet, how to treat this ailment? For I remember well Father’s return to Bourne as a famous man with an annuity of £1,500. It was with these funds he opened Shillingthorpe Hall, his second sanitorium, following the model of Greatford Hall, his first success.

I should think you will never meet my father, for he is loath to travel now and is a sanguine fellow and formidable when formed of an opinion. It was my ardent hope that he would change his mind, but he is a man of iron intent, defined by his dedication to unambitious, all but artless, service of mankind.

His is a long shadow, and I but a Pygmy within it.

As a boy, I saw him treating those men and women all thought mad beyond mortal aide, all of whom he set to work on the lands of Greatford Hall. He put them to labouring as ploughmen, gardeners, threshers, thatchers – all attired in black coats with white waistcoats, black silk breeches and stockings. Each looked so neat against the russet earth and wide sky.

He even had the head of each bewigged, well powdered, neat and arranged, and it seemed a miracle that in that atmosphere of health and cheerfulness, he aided in the recovery of every person attached to that place.

Perhaps, Mary, you are unfamiliar with the ways of the asylums, but they are, for the most part, rotten places – little better than prison cells. Across this land, Christian souls are abandoned to gibber in their filth, but Father has always said, ‘treat a soul as less than human and so their faculties will remain’.

His methods were in contrast to the likes of Baillie and Heberden, the first physicians to treat the king. Great men of their day, but they did burn the monarch’s skin as if he were possessed by a demon, striking his person and restricting him within the confines of a straitening jacket.

The bleak nature of these treatments was hateful to my father, who instead set the king to work, of all things. So it was that His Majesty took to planting flowers in the great gardens at Kew, engaging in daily exercise and toil, with the companionship of my father and John.

This is how King George recovered. Yet now his illness has returned with threefold strength, and knowing its root cause, I fear there is little hope – though to say so may be treason.

You see, when John, who had accompanied our father at Kew, returned to the practice at Grantham, he was quiet on the matter of the king. I spent many an evening and a good deal of port wine in an effort to loosen his lips, but John is a faithful and trustworthy man, irrespective of the £650 he receives annually from the king as reward for his past labours.

When I would ask of him, his face would darken and he would say, ‘Robert, speak not of it,’ and I would know to let it be.

Only now, with father too old to travel, as you know well, it has fallen to John and me to attend His Majesty. And so, before we came here to Windsor, John finally abated and revealed to me the truth.

I remember his white face and bright blue eyes as he spoke, his hair already grey as wire. His nervous disposition caused his fingers to shake about his wineglass and he looked down as he spoke, as if ashamed.

‘The trouble,’ he told me, ‘began in 1775, Robert. Much earlier than most know. For it was then that the king first saw him: the green rider, galloping through Windsor Park.’

It took a while for John to explain it fully, but it seemed the rider he alluded to was a phantasm seen only by His Majesty. A stag-headed man, he said, with antlers growing from his hoary skull, his skin covered with myriad mosses and lichen.

When John first told me of it, I laughed, thinking he was pulling my leg, but he shot back such a look of thunder that I knew I had transgressed upon his honour and that of the king, and I so begged forgiveness both of him and the king, and of the Lord, our saviour.

Thusly, I learned that the malaise began in earnest when, across the wide Atlantic sea, battles were raging at Lexington and Concord. Our American brothers had risen up against us and so, amidst this bad news, it was said the king first noticed the green rider about his palace at Windsor, thundering through the park on a horse of leaves and tree roots with eyes of coal-red flame.

There are legends of this place, Mary – of that rider – stretching back to the time of Queen Elizabeth and earlier still. It’s said that on the threat of Spanish invasion, she saw him and called on Dr Dee, who also saw him and heard him, rattling his chains and leading hounds of pale blue fire about her forests. It’s said that after he’s seen, all the cattle hereabouts give not milk but blood, and for as long as there’s been an England, when it’s threatened the green rider will appear.

My father, being an ardent student of nature, thought these stories of the king’s to be some form of delusion – a children’s story heard by His Majesty as boy, twisted into a living fantasy.

So it was that, although the king was said to often speak to the rider, who he said came to his chambers, communicating to him in an endless, babbling stream of speech all through the night as well as the day, once repaired to Kew, away from the ancient forests of Windsor, the monarch made a recovery. My father was said to have convinced him, in time, that his talk of the green rider was but a product of an overactive mind.

With this knowledge, John and I attended His Majesty at his palace at Windsor, beginning our treatments last August. And though I came to that most grand of palaces with no doubt in my heart or my mind that His Majesty’s tales of the green rider were but delusions, I have now learned better, and I must speak of it to someone.

John has sworn me to silence, and so that someone, my darling one, must be you.

You hold all my great secrets, the most sacred of all of which is our son, and though it is a burden, you must keep this one too, for as long as you live and ever after. And though you may think me mad, know, my love, that I am hale and well, but have seen such things as would shock a lesser man to death.

As I have told you before in prior missives, attending to His Majesty is not a task for all hours of the day. The king is in a weakened state and must spend some hours at rest. So, between John and I, it is not unknown for us to have spans of several hours in which to perambulate the woods and gardens surrounding the palace.

Even now, they are subject to countless improvements by none other than that great architect of our age, James Wyatt, whom I am yet to meet but one day hope to. It is a place of marvels to walk through, Mary. In recent years, it was the great work of Paul and Thomas Sandby to improve, with the Long Walk as laid out by Charles II flanked by elms planted by William of Orange. It was the Sandbys who expanded the lake at Virginia Water, adding a waterfall and the Obelisk Pond dedicated to the king’s brother, the Duke of Cumberland as he was, God rest his soul.

It is a place of great tranquillity for the most part, and of great magnificence. In one area, there is a complete set of ruins built by ancient Romans – ruins the king himself had brought by ship from Tripolitania on Africa’s Barbary Coast! I have walked amongst these ruins and touched them, and thought of the same sun shining on those stones that shone on Julius Caesar in the days of antiquity.

Greatest of all though, Mary, are the oaks. For in the great park at Windsor there are oaks that were planted in the days of King Offa and before. Trees that were acorns in the year of the birth of Christ.

Who might have guessed it would be one such oak that would ruin our king and wreak havoc upon his mind? For it was in the year 1796 that our doom was spelled by a team of men with axes. Men who felled the tree in which the green rider once slept.

I learned of it one night when, having laid the king abed, I went walking in the Little Park – which is not little, being over 600 acres.

I was strolling beneath a blanket of stars, pinprick bright amidst the shroud of night, when I heard a sound not unlike that of twigs snapping underfoot. But it was not twigs. It was the flints of a pistol clicking back into their place.

‘Who goes there?’ came a rough-sounding voice, unmistakably that of a Londoner who I thought must be a rogue or highwayman. ‘State your name and purpose, or I shall shoot you in the name of the king.’

Well, I did state my name and my purpose, and learned that this fellow, of the name of Brown, was none other than a groundskeeper at work under the auspices of His Majesty. He told me that though the king had all the deer of the Great Park killed or chased off before even my father attended him, it was still the duty of Brown and men like him to patrol thereabouts in case of thieves or poachers.

‘But I’ll tell you now,’ Brown said, ‘you need not fear of poachers here. Only the unwise stalk this stretch of land at night, all round here know, elsewise Herne the Hunter will give chase and know them for his quarry!’

He scared me how he spoke, with a black-toothed smile. It was the first time I had heard the name, but I learned then from Brown of the history of Herne the Hunter and of the ancient oak in which the spirit of that forest used to dwell.

‘Some say,’ Brown told me, ‘he was once a poacher, caught by King Henry, wrapped in chains and hanged upon that oak. Others say he was a cuckold, for wearing antlers is a punishment of old for those what cannot contain the lustings of their wives. But I know the truth, for I’ve seen him, and if he’s not an ancient spirit of this land then I never lived. And since that oak came down, he’s bound to nothing. He’s free to ride, and does, you mark my words.’

I parted from Brown that night, shaken but resolved. I reported to John what I had learned, and he thought me a fool for believing Brown’s stories. But I said to John – warned him – that if it were true and the king had cut down the oak in which the green rider dwelt, perhaps that was the cause of his worsened condition.

John made me swear I would not speak to His Majesty of it, and for a time I did not. But last night, which was a quiet evening, I did just that, saying to the king, ‘Your Highness, tell me of Herne the Hunter.’

No sooner had I said the name than His Majesty turned as pale as snow, his mouth forming into a small, white-lipped circle, his words falling out of him like his voice was very far away. ‘Tried to chase him off,’ he told me. ‘Had the deer shot. No more antlers. No more horns. No more drumming. No more drumming in the dark.’

I knew I had made an error, for then the king would not speak sensibly for many hours, rambling again of the dark drummings he had heard and of the green rider, his hounds, his horse of leaves and roots, and the language which echoed in his thoughts but that could not be understood.

In time, I had no choice but to treat him. I gave him a dosage of laudanum to make him sleep. And once he was calmed, I stormed from his apartments and went myself, my face hidden in shame, out into the Little Park. I pulled my cloak about me, cursing at myself and intending to find Brown and learn more of the ancient spirit in hope that I might do something to help His Majesty once and for all.

But the park… it is so big, Mary. And the trees are so high, and their foliage so abundant, that though I thought to cross one part quickly, ducking into the treeline and emerging near the site of the fallen oak, I became turned around and then sorely lost, wandering for what felt like hours.

I had time, on that walk, to think of a great deal.

I thought of you, Mary, and little Robert, and of my father, and the hopes I have as a man. For it is my will to lift mankind out of the darkness and better the lot of those thought mad and beyond repair. And my failure to do so for our king, the shame of it, saw me suddenly set to weeping, knelt in the tangled ferns of the forest floor.

I smelled him before I saw him.

It was as the smell after a thunderstorm, mixed with the wet and heady stink of peat. It made me start up, as if to stand, but then I froze in fear, hearing Brown’s words in my mind. For if I moved, I feared he would consider me quarry and hunt me until his hounds tore me apart.

Oh, the hounds, Mary. You can’t imagine them. Moving like a river, tumbling, surging, flowing in shimmering blue, like a glowing wave of blood. Though they howled and barked and scratched and leapt, they were silent as a tomb, moving through the trees and round about like floodwaters with ears and tails and teeth.

But his steed was not silent. Neither was it a horse, nor even much of a horse’s shape. For though once there may have been the skeleton of a stallion beneath what it has since become, the animal is barely recognisable. Its hide is not leather or hair, but made up of a thousand, thousand leaves of birch and ash and alder, hazel, spruce and yew. Its mane is of holly, run through with berries red as blood. Through and about its mighty limbs run roots thick and thin, some delicate, spiralling like spiders’ webs, and where its legs touch down flowers bloom and fade in seasons which last but an instant.

And atop that steed, in a saddle made of fungus grown wide and slick and yellow-grey with age, speckled with mushrooms and toadstools, masked in a haze of spores and pollen, rides Herne, the most ancient thing in all imagination. His garments looked like faerie clothes, sewn of moss and blackest fur, run through and threaded with silver and gold. All about him, he wore not chains but ancient leather straps, loaded with tools of flint and bone.

In one hand he bore a horn, cracked and split, as if hollowed from the head of an aurochs or some ancient, bull-like beast, black and shining terribly. His beard was long, made of tendrils of tree roots, grown blue and green with lichen of every kind.

And on his head was a skull – the skull of a great stag, white beneath the moon, antlers stretching wider than the span of an albatross, shooting from his head like captured sunbeams, vicious points of bleeding velvet, ragged, hanging, covered with bells which did not ring and signs on stones I could not read.

His eyes, Mary, were just as the king had said. Like coals, burning.

So were his steed’s.

And though the vision of him is something I will never forget, it is the sound of his voice that haunts me. Like the breaking of stones beneath water or the splintering cracks of a sapling bent back far too far…

There was the wind at the edge of it, whistling through grass, weathering rocks, and the sound of it smelled somehow – his words stinking like a storm lashing a desert, making it grow with slimy things that walked and spoke his tongue and followed after him.

He turned to me and spoke, and I saw then the crown upon his head, made of twisted gold, and about his waist a girdle holding a sack.

As his steed moved by, grains spilled from that sack, ghostly white as moonbeams, landing on the forest floor and vanishing where they fell.

It was then, Mary, that I felt myself losing my mind.

So, though he spoke, the rushing, heady smell of his language drowning me, clattering and clicking, buffeting and breaking, I closed my eyes and prayed to God, and thought of the best thing I could in this world.

It was you I thought of, Mary. Of your love. And it was you, your face, in my mind, which made all his horrid words go quiet.

When I opened my eyes, he was gone. And I wandered many more hours, lost in those woods, until Brown found me and led me back to my apartment.

I don’t know what to do now. Whatever must have trapped him, felling that oak has freed him and no force on Earth can contain him, of that I am sure.

For the king I can only do so much, for he is not mad, but knows the truth: that England is in crisis, and so long as this state remains, so he, Our Majesty, will not know peace.

Of all the things I can do, there is only one that I am sure is right, and that is to love you, Mary.

And I will do, all my days.

How I wish you were here to hold me.

How I fear that creature will return.

Oh, I must rest. Soon John will come and expect me to attend to my duties.

I love you now and always, Mary. May your face be the one I see when I dream.

Yours always,

Robert Darling Willis, M.D.

3

A Promise Kept

A Buckinghamshire Tale

Questions about life after death and the nature of the soul have always fascinated human beings.

This tale concerns a very specific visit to the Christopher Inn in Eton by a ghost intent on keeping a promise. Major George Sydenham and his friend Captain William Dyke, who were soldiers together in the reign of Charles II, often debated the existence of God and the immortality of the soul. They made a promise to each other that whoever died first would visit the other as a ghost. This is a reasonably straight telling of the contemporary account of this arrangement, although I’ve also included such classic ghost story tropes as the link between a spirit and an item they once owned and a warning to the remaining friend to mend their lifestyle before it is too late.

The Christopher Inn, a coaching inn dating back to the early sixteenth century, is now a boutique hotel. It can still be visited today, but, as far as we know, this particular ghost has never visited again.

EC

It was easy to forget the desperation of war, as we sat in the cosy parlour at the Christopher Inn in Eton, drinking brandy and reminiscing.

I was glad to see my Major again, as I always am. Although war with the Dutch was a memory now, and it was some time since either of us had seen active service, nothing brings men close like the immediacy of conflict, the terror and excitement of bombardment, of rapidly changing orders, of the knowledge that at any moment one friend might be lost, leaving a void in the other’s life.

At that time, I thought that the person living with that empty space at his side might have been the Major, as I was wounded in the attack on the fort where we were stationed and though the wound proved to be superficial, I did not know that in the moment. I was caught in the shoulder by a bullet and would have been cut down as I lay in my own blood by the Dutchman who fired the shot. He stood teetering on the top of his ladder, levelling his musket at me, but in a moment, he was toppling backwards and falling to his death below as the Major drove his shining sword deep into the enemy’s heart.

He had rushed to my side, and I remember how blue the sky was that day as he leaned over me, pressing his hands to my wound to staunch the blood, his arm supporting my weight. I opened my mouth to say farewell to him, thinking my life was about to ebb away, but he pressed his hands still harder to the flow of blood.

‘Stay with me, William. Today is not the day your soul will go to God.’

Even as I slid between states of consciousness, I remember being unsure about that. The Major and I had often debated the existence of God and the immortality of the soul. It was a subject I had never been firm upon, and at that moment, lying on what I feared was my deathbed, I was even less sure. The existence of God was not something I could assert, and if He would want me was something even less certain.

The Major got me to the surgeon in time to extract the bullet, which fortunately had not pierced all the way through my shoulder, so I never found out one way or the other. Our friendship continued, greater than ever, strengthened by the bonds which can only be forged in the furnace of war.

Still, I was struck by how different a scene it was now, nestled in the warm back parlour at the Christopher, with freezing rain lashing the windows outside and a blazing fire inside. I was glad to see opposite me the familiar features of George Sydenham, my Major, the man