Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Allen & Unwin

- Kategorie: Für Kinder und Jugendliche

- Sprache: Englisch

Based on the lives of real people in Somerset on the borders of Exmoor, Miller tells his own story of a young labourer swept up in the adventure of riding second horse in a west country stag hunt. Finding himself in a closed social system in which he has neither status nor power, the young man identifies with the aberrant Tivington nott stag, which, despite its lack of antlers, has become a legend in the district for its ability to elude the hunt and to compete successfully with the antlered stags in the rut.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 260

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2017

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

THE TIVINGTON NOTT

Alex Miller

My thanks are due to the poet Kris Hemensley. During the early 1980s, in his occasional magazine H/EAR, Kris published some pieces of mine in which I referred to the Nott of Tivington. It was the enthusiastic response we received to these pieces that encouraged me to write this story.

This edition published in 2005 First published in Australia by Penguin Books Australia in 1993 First published in the United Kingdom by Robert Hale in 1989

Copyright © Alex Miller 1989

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. The Australian Copyright Act 1968 (the Act) allows a maximum of one chapter or 10 per cent of this book, whichever is the greater, to be photocopied by any educational institution for its educational purposes provided that the educational institution (or body that administers it) has given a remuneration notice to Copyright Agency Limited (CAL) under the Act.

Allen & Unwin 83 Alexander Street Crows Nest NSW 2065 Australia Phone: (61 2) 8425 0100 Fax: (61 2) 9906 2218 Email: [email protected] Web: www.allenandunwin.com/uk

National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry:

Miller, Alex, 1936– .

The Tivington nott.

ISBN 1 74114 778 6.

E-book ISBN 978 1 92557 606 1

I. Title.

A823.3

Typeset by Midland Typesetters

In loving memory of my mother and father

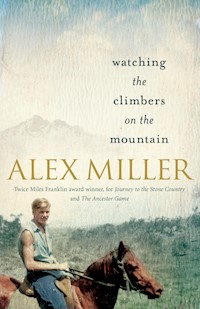

Alex Miller at 16 years, West Somerset Farm, 1953

Morris, the genuine West Country farm labourer

AUTHOR’S NOTE

The events in this book took place in 1952, more or less in the order in which I have related them, and the characters in the story are all based on the lives of real people—I have even used some of their real names. I was myself, then, the nameless youth at the centre of this narrative—that self-conscious imposter in the photograph on the facing page. I say imposter, because a comparison of my photograph with that of a genuine West Country farm labourer—the figure of Morris in the photograph below—will reveal my pose to have been not original and my own, but a copy merely of his authentic style. My half-smile is surely an admission of my awareness of the ironic potential of my situation. I was, after all, a boy from London, who successfully posed for two years as an Exmoor labourer. But it was a pose and, although it was not as easy to maintain as it might seem to have been from this distance in time, that is all it was. It did not last. Eventually I became a novelist, who is another kind of poseur. As a novelist, I have been not so much a liar as a re-arranger of facts. That is the kind of writer I am. The purely imaginary has never interested me as much as the actualities of our daily lives, and it is of these that I have written. Although this story may not be autobiography in the conventional sense, it is nevertheless deeply self-revealing of its author. All the episodes, not just a few of them, may be traced back to actual events and experiences in my life, and in the lives of the people, and of some of the animals, portrayed here. There was such a stag as the Tivington nott, a horse such as Kabara, a cocky Australian who owned him, a farmer for whom I laboured for two years and who had rightly earned the nickname, ‘Tiger’, a labourer by the name of Morris with whom I lived, a harbourer who would know himself in the figure of Grabbe, and a huntsman of the Devon and Somerset who broke his neck while chasing a hind one winter afternoon. I loved them all, and loved the landscape they inhabited. Briefly, they were my reality.

Alex MillerCastlemaine 2005

The doctor told Morris yesterday that he shouldn’t eat so much raw pig fat. It would probably kill him before he was forty. But it is the staple diet of labouring people in this locality. Morris is not from here originally, though his wife is—her parents eke out an abandoned existence in a decaying stone cottage up behind Monksilver in a sunless cleft of the moor; a situation that gives me the creeps. Morris is a native of the open downs of Wiltshire. Boarding with him, he has become my friend. His uncle, Tiger Westall, tenants this place and Morris serves him honestly, but is his own man despite that.

Even though he is a real grinder I did not mind working for the Tiger. He is not just an uncomplicated farmer. His hard good sense about managing the farm deserts him when it comes to the matter of hunting the wild red deer on Exmoor. He fears this passion as a disability and is forever guarding himself against it. Everything he does is complicated for him by this duality in his nature. He tried to get me to address him as ‘Master’ when I first came here from London two years ago. It is the tradition and Morris abides by it. I respect traditions and have one or two of my own. One of them is not calling people ‘Master’. I could see how much it meant to the Tiger to have me conform, however, so I did have a go at it, just to be fair. But it was no good. I couldn’t look him in the eye and say it. I wasn’t being stubborn. There was more to it than that.

He carries a hawthorn stick—even when he has a weighty four-gallon bucket of hot pig mash in each hand he carries this stick, jammed under his armpit. On this occasion he considered using it as a weapon—he was not accustomed to arguing with labourers. But I am a glutton for hard work and he had seen enough of that to make him hesitate before giving me a thump and firing me straight off the place. Also, there was this other complicating matter that I was not aware of then.

So, we’re standing here in the yard confronting each other.

‘I won’t be calling you Master,’ I say.

Morris is interested. But he keeps carrying forkfuls of hay across from the yard-rick to the cowshed, discreetly observing developments between me and the Tiger.

And Tiger’s wife too. Watching the Master straightening out the boy, stationed in the doorway of the dairy—her kitchen. Vigilant, round and fat and all in white with tiny black eyes peering out. Keyed up. Trouble on her doorstep. Ready to make a stand over this. She’s been expecting it, looking for it—boys from London cannot be trusted! She’d like to see the Tiger chase me off the place. My decision not to call him ‘Master’ is proof of what she’s been saying all along.

The Tiger in front of me, hunched up and tense, red in the face and gripping his hawthorn stick. Not sure how far my rebellion might go and ready to take a swipe if necessary. ‘You will treat me with respect, boy, or I shall hunt you this minute!’

Serious about it!

‘I do respect you, Mr Westall. And if it suits you I will call you Boss.’ My polite offer takes him by surprise. Something new to think about. For maybe five or six seconds he crouches in front of me, holding on to his reaction—considering now where an advantage might lie. Then bang! he slams his stick against the corrugated tin of the bull pen and makes me jump half out of my skin.

‘Boss, eh?’

‘Yes.’

He’s delighted I jumped and he lets it sink in; keeping me in my place with fear. Then he brandishes his stick and turns away, heading for the dairy door and Mrs Roly-Poly; ‘Get on then, boy.’

It was too easy to call it a victory. That I owed him something for dropping ‘Master’ was a certainty.

But what I owed him only began to emerge with Kabara the black hunter.

Last April it was, and we’re on the point of a testing manoeuvre. One of my big chances to be a hero around this place. So of course I’m saying nothing. Keeping quiet. Slipping into the background and waiting for Morris to do the dirty work. He won’t complain. There’s a cow on heat and we’re about to release the bull from his solitary confinement.

When he’s not actually doing his business this two-and-a-half ton animal is secured by the neck with something like an anchor chain in a pen not much bigger than he is. Restless is not the word. He’s got the insane yellow eyes of a cornered cat. A killer if ever I saw one. Eaten up with soured energy. Spending his days and nights lunging from one end of the chain to the other, smashing his scarred horns into the steel framework that confines him. He’s on the look-out for vengeance!

Letting him out is like loosing a homicidal maniac for a spree. It’s always touch and go. The whole enterprise teetering on the brink of injury and destruction of property. A set-up looking for damage on a large scale.

So we prepare for it solemnly.

No mucking about or high spirits. No comic conspiracies between me and Morris against the Tiger. Everything tight. That’s the mood on these occasions—do the best we can then let fate take its course.

First we chain shut the gate to the main road. A sow once lifted this gate clean off its hinges and the bull would go through it without turning a hair. But we chain it shut all the same. It’s a ritual with us. Getting our courage up. Pretending we’re in control. Putting off the moment when Vern Diplomat V11 gets his taste of freedom.

I let the cow out from the stall into the small yard behind the milking shed and she stands there chewing, her brown eyes half closed. Then I go and open the gate through to her from the big yard, which the bull will have to cross. The Tiger meanwhile chaining the orchard gate.

Chains everywhere!

We’re almost ready. Roly-Poly observing from behind the upstairs curtains. Everything quiet down here in the yard except for the smash of those big horns on the buckled frame. He’s shifting from one foot to the other and letting out a bit of a moan every now and then.

We’re all set.

Me and the Tiger step back a bit and look at Morris.

I’ve got my pitchfork. Tiger’s got his stick. What a laugh! I’m supposed to guard the gate to the orchard in case the Diplomat decides to go off in that direction. Tiger will stand with his back to the dairy door, ready to bolt into the house should the bull head his way.

The bashing in the bull pen stops. We look at each other. The old boy must have caught a whiff of the proceedings. Silence for three seconds then he goes crazy, bellowing and moaning and hurling his great carcass around.

‘Let him out!’ the Tiger says, and he turns away, going for the dairy and safety. I look at his broad flat back and then I turn to Morris. Morris smiles and goes off to do his job. I could stick the Tiger with my pitchfork! Drive a steel prong through his tweed jacket and deep into his lung. Dig it in. See Roly-Poly come shrieking from the house. And dig her too! Something worse than her dread of all this. Be a mad bull myself. Go on a rampage! They don’t care if their nephew gets pulped in that pen.

I go over and take up my position by the gate.

I’m waiting.

I’m ready to make a run for it.

The yard is empty. Morris is in there. On his own with the bull and he’s stretching out on tiptoe over the horns trying to reach the release pin on the shiny steel chain—polished by the greases from the hide. A sudden swing of that loaded head and Morris will be crushed. But the Diplomat’s probably sitting back hard on the chain, keeping it stress-tight, rolling his sick eyes and choking on his tongue, fired up to go and break that cow’s back with one almighty thrust. Too lunatic to co-operate. Just wanting to jump her then smash everything in sight.

I’m waiting for him to come out.

And I feel certain that if I were to drive the steel tines of this pitchfork into his eyes I wouldn’t stop him. He’d just keep coming into the pressure. Something in his nature.

I look across to where Tiger is standing by the door. It’s too far to see the expression in his eyes. I know it anyway. Sullen at this point in case something goes wrong. Then he’ll go bright red in the face and start screaming abuse at Morris. Roly-Poly backing him up. Like a couple of maniac woodland trolls. The whole world conspiring against them. Morris a disloyal, useless nephew who should never have been given a job. And so on.

The moaning and choking is still going on in the pen.

I’m set to take off the minute things get out of hand. It’s a matter of personal survival. If Morris should fall under the bull when he comes careering out that door on to the cobbles I shan’t be rushing over to distract it. I’m not living in a land of heroes and legends.

Here he is! The huge red carcass slamming through the door! Going too fast to know where he is, and bigger than I remember him. He hesitates, then catches a whiff of the cow and away he goes, ploughing his way clean across the corner of the dung-heap, moaning and bellowing and spraying shit all over the yard. Morris after him, yelling and waving his arms, pretending to be doing the steering. But really this is all just a matter of hoping for the best. Letting nature take its course. Standing back and watching the miracle of procreation.

And he’s on her! Up on his hind legs and heaves one into her. Love at first sight.

It’s all over.

Now he’s looking around to rip one of us apart. He swings his head and hauls a two-hundredweight chunk off the dung-pile. Spoof! he whams it into the dairy wall. Shit everywhere. Then lets out a shriek as he spots Morris heading for him with an armful of sweet golden mangolds.

If it was up to me at this stage we’d all clear out. But Morris believes in seeing things through.

There has to be a better way of doing this.

The trick now is to lure the Diplomat back into his pen by leading him along a trail of mangolds. The idea being that if we can keep him busy gutsing himself he might forget to kill us all. I can’t believe he won’t catch on to this strategy sooner or later.

I must endure it while he inches his way back across the yard, lifting his head every step or two between bites and spraying some saliva around, keeping us in mind of what’s on for afters. Between shifts at laying the bait-trail, Morris—he’s doing all this on his own as me and the Tiger are frozen to our spots—slips into the pen and hangs up the chain so that Diplomat will put his head into the noose when he goes for his final titbit, a honeyed bowl of sugarbeet!

It’s really quite a nice day, if only I were free to enjoy it. The sun has come out and is warming me through my jacket. Not that I’m actually beginning to relax. I’m not doing that. But I am letting myself hope that the bull will go on doing the right thing. I can see the Tiger inching forward. Morris sees him too and waves him back. It’s too soon to rejoice. I’m staying still as a rock, letting my eyes roam around, keeping tabs on the scene. Watching that big slobbering mouth stuffing itself full of sweet pulp. And the Diplomat’s checking me every now and again. Making sure I’m not trying to sneak away.

It’s maybe another ten yards to the bull pen when this retired Australian army officer who lives about half a mile down the road from Morris’s cottage, at Gaudon Manor, Major Fred Alsop, jumps his stallion Kabara over the road gate into the yard.

I suppose he thought we’d be impressed with his horsemanship. After all, leaping from tarmac onto granite cobbles over a fixed gate at least four-foot-six high on a fiery stallion of around sixteen hands is a fairly out of the way thing to do round here in the middle of an ordinary working day. It’s unexpected.

There’s sparks actually flying out from the horse’s shoes where they’re slamming and sliding around and he’s practically through the bull before he can pull up. But there’s not a lot of control in it that I can see. And the horse doesn’t know what he’s jumped into. It’s not hard to tell. He’s confused and excited. Wondering what he’s supposed to be doing next.

That’s what we’re wondering too. We’re all assuming, I suppose, that Alsop has some plan of action that he’s about to carry out; and we stand there gaping, waiting for him to get on with it. The Diplomat as well. He’s taken by surprise like the rest of us. Half a dripping mangold hanging out of his mouth. Staring.

And meanwhile the black horse is leaping and rearing around, threatening to pound Alsop into a stone wall any second. And the major himself only just staying up there, reefing and jerking on the reins, ripping the bit backwards and forwards as if he’s riding a one-wheeler for the first time.

A spectacle! Alsop, sixty years old, wrinkled, skinny, got up in the garb of the local gentry, living out some crazy idea here in Tiger Westall’s yard! All the way from the other side of the world. Paying a social call. Being a trick rider. Something! An Australian horseman in fancy dress prancing around on Exmoor. Out of a book, this bloke. A tourist!

The Tiger’s the first one to wake up and he starts yelling and waving his stick. Trying to get in a jab without coming into danger. A dwarf attacking a giant! ‘Get on out of my yard, you mad bastard!’ Something like that. Incoherent. Okay to sell this fancy prancer hay and milled oats and one thing and another at twice the going price! Laugh at him behind his back. Dig your neighbour in the ribs when you see him turned out with the Staghounds. Terrific! But the Tiger’s not going to put up with this. You can see that.

I’m enjoying it.

I’m hoping the Tiger might get a bit trodden under foot.

The bull takes an off-hand look around at all this capering and yelling and he tosses his head and walks straight into his pen. Going for the honeyed sugar beet without any more fuss. Morris is in after him in a flash and has him chained up again.

Alsop’s off the horse by now and he and the Tiger are working something out. A bit of heat from Tiger, but after all, this man’s got money to spend and there’s no real harm done. I’m ordered over to hang on to the horse while they go into the house for a drink and a chat to settle it all up. Alsop greets me by my first name but I pretend I don’t hear him. I’m glad to see the back of him. Tiger’ll fix him up. And that’ll cost him a pound or two one way and another. Still, he’s ripe for it. He’d be over at the cottage attending Morris’s card nights, this bloke, if Morris weren’t a bit too cagey for him. He’s a dreamer. That’s clear.

Morris comes to the door of the bull pen and stands in the sunlight and rolls a smoke. His back to the Diplomat. Everything under control. Taking his time. Getting his reward now. Idling. Enjoying the moment of leisure while he attends to the details of his own pleasure. He doesn’t look across at me. Not on this occasion. He’s no help when it comes to horses. He’s not interested in this impressive entire that I’m hanging onto. Tractors. Motor cars. He knows all about them. Machinery. That’s his idea of what it’s all about. Given half a day off he’ll follow the hunt from the front seat of his motor car with a pair of binoculars. That’s the way to do it, according to Morris. Stay dry and comfortable. Never far from a thermos of tea, and if things don’t work out you can head home without any fuss and bother. That’s the way he goes hunting. His wife beside him. They’re very close those two. There’s a lot I don’t know about them. It’s another world. And they keep it closed. But horses are his blind spot. And this animal of Alsop’s doesn’t impress him. He doesn’t want to know about it. Anyone else would come over and start theorising about breeding and condition and schooling and all that stuff. But not Morris, he wanders away after a minute, down to the orchard to take a look around.

I’m left here holding the stallion on my own. Like Diplomat, I can see there’s no fear in this animal. Energy! Lots of energy. And maybe a touch of insanity too. But no fear. He’s shivering, a continuous tremor running over the surface of his skin. Prepared for anything. Ready to go. So I decide to walk around with him. Something to do. Show him the place.

He can kill me if he wants to. The decision is his. He’s a big energy-packed aristocrat stepping alongside me. Keeping the reins loose. Not hanging back and waiting to be led, not waiting to be told what to do. None of that. Not plodding along behind me but right here next to me. Head up and alert. Intelligent. He’s not going to miss anything. Wanting to check it all out. Wanting to know where he is and what it all amounts to. He has a curiosity in him that alerts me too. A matter of paying attention. Keeping my mind focused.

We go along, from one end of the yard to the other. He stares into the bull pen, nostrils working, eyes seeking it all out in the half-light of the interior where the massive bulk of Diplomat is imprisoned.

Shoulder muscles just brushing against me as he breathes.

Let’s move on!

His decision.

What’s over there? I go along with him and he hurries me, energy flowing through him, moving me faster than I want to go comfortably, making me keep on my toes. Then he stands and stares at the cow. She’s chewing again. Her back still arched. Big brown eyes dull and dreamy. Set for eternity! Kabara lets out a tight, aggressive grunt and moves away sharply, almost wrong-footing me, his head going down without warning; snuffling the cobbles, grunting and blowing.

We complete the circuit and stand in the middle of the yard. Surveying the scene. Has he missed anything? He is still. His hard-muscled shoulder leaning against me. And it begins to seem to me that he doesn’t mind being with me. I can feel it. The way he’s looking out and away from the two of us. And not peering down sideways at me, suspicious of what my intention might be. I try returning the pressure of his shoulder, wondering how conscious he might be of my touch. I’m not pushing at him, just holding a pound or two firmer. He’s a sire! Words like noble, beautiful, heroic, they’re making sense. I’m beginning to see what all the fuss is about.

It’s something new to me.

Tiger’s two chestnut hunters don’t have it. They are just horses. Nobility doesn’t come into it with them. H for horse. That’s about it with Tiger’s geldings. I should know. No comparison to this thing of Alsop’s. May as well be another species. Horseradish.

It’s looking after Tiger’s hunters that’s my special job. My particular area of responsibility you might say. The horses belong to me the way the machines belong to Morris. And the Tiger tutors me himself. It’s not all fun and games. Clipping, shoeing, grooming, feeding, exercising, cleaning out, polishing the gear, worming, whatever. You name it. He likes to turn out just right on hunting days. He doesn’t want anything left to chance. Hunting is his reward in life for all the skimping and grinding. Hunting the wild red deer. They’ve been doing it here since the Anglo-Saxon kings were around. It’s not something they just decided on yesterday. It’s in their blood. And the Westalls have been here forever, so when it comes to his hunters the Tiger watches me every inch of the way. Criticising mostly. Offering abuse. Sarcasm. Looking for perfection where it isn’t to be found. If he says nothing I know I’m doing extra well.

I do the best I can. But perfection is not something you can get from those geldings.

Kabara, I’m deciding, is another story. I can feel the quality of this beast standing next to me. It’s got something to do with ancestry. Breeding. Lineage. Stuff like that. Oats and polishing and clipping and grooming won’t fake it.

The horse and I make the decision together and walk over to the gate. We stand staring down the road. Just looking. I have read in an old book on venery that men are better when riding, more just and more understanding, and more alert and more at ease . . . The sun is warm on my back and the day is calm. Going on towards noon now, and everything quiet down the road.

But that was last April when, despite the warmth of the day, there were still packed scallops of dirty snowdrift left out in the sunless hollows of Codsend Moor and Dunkery Hill. Remnants of the vicious winter that had gone before. And the strange sight of the new shoots of the deer sedge and the dark green cotton-grass poking up through flutes of melted ice, where the peat bogs had frozen to a depth of eight inches and more during the February blizzard.

Alsop and Kabara both a world away then from where they are now.

Alsop and his wife got smashed up coming back from Taunton at high speed one night in July. Midsummer and living it up. Carefree! Driving like a young man and the T junction at Handycross slipping his mind. So they hit a four-hundred-year-old wall. Which wouldn’t have happened to a local. No matter how carefree. A reflex swing of the wheel at that point and a local would have gone past laughing. One of the dangers of being an alien. A local’s always got something extra on you. They can feel the shape of the country in their bones. And they can afford to wait for outsiders to make a mistake. Saying nothing. Being there and waiting. Like the wall. Six foot thick. A remnant from a sturdy past and Alsop speeding along with his foot held confidently on the throttle as if he were still in the emptiness of Australia.

She’s probably going to keep going till she’s a hundred, but he’s finished. You’ve only got to look at him. Getting out of the house is just him proving to everyone that he can still walk. Grey and struggling. Whatever it was that got smashed inside him, it will never come right again. He’s not certain whether he can still hope for something or not. No confidence about anything now. It’s downhill all the way for him from here. Staggers and slogs his way across the fields, struggling against the wind, and stands there panting, watching me and Morris getting a putt-load of mangolds out of the clamp. You get the feeling he’s about to hop in and start helping you. Then he’ll see we’re not breaking our rhythm and he’ll pass some remark. A comment he’s made up. Nothing much. And away he goes. Dragging himself back the way he came. Pausing on the horizon to wave his stick and look down on us. Morris has been kind to him from time to time and I suppose that’s it.

He came to the stables a couple of times and stood looking at Kabara. Nothing to say on those occasions. There’s always been something about him that was totally out of step with this place. That couldn’t be accounted for simply because he was a foreigner. Something that led him from time to time into being ridiculous. He turned up at his first meet of the Staghounds wearing hunting pink. Everyone, except him, knew this was something reserved for the Huntsman and the whips, but no one said a word to him about it. They exchanged glances, not smiling, not passing judgements, and they looked at each other again the same way when they heard he’d hit the wall at Handycross.

I could have told him. You’ve got to keep your head down in a place like this. Take it all a step at a time. Wary! Charging around in red coats and leaping bang into the middle of them on black stallions is not the way! Provide yourself with back-up and keep something in reserve! Let them do some of the guessing.

His wife came over to see the Tiger a couple of days after the smash. A few scratches and a bruise here and there, but apart from that you can see she’s going to live forever. One of that sort. Hardy. And a touch of luck about her. The kind that walks away from a bomb blast with all her clothes blown off but herself still intact. A cigarette stuck in her mouth all the time and messy-looking. Wearing an old black dress and gum boots. Not the peacock of the family in other words. And swearing a lot. Which has the Tiger on edge at once.

She wants someone to look after the stallion till things get back on an even keel. Can the Tiger assist? She’s practical. Matter-of-fact. Straight to the point almost before she’s through the front gate. No hedging around with, It’s a nice day, or, How are you? Just, Let’s go! Let’s pick up the pieces and get things rolling again! That’s her attitude. You can see the way she operates. Not in mourning for any lost dream. Expecting everyone to drop what they’re doing and to start listening to her. Every now and then there’s a hint of an English accent in her voice that makes you wonder. And she has an aggressive way of looking at you suddenly, when she’s not actually talking directly to you. Challenging. As if she almost expects you to be on the point of disputing what she’s saying. I get the feeling she could come down pretty hard on someone she decided not to like.

The Tiger comes to some financial arrangement and I’m sent off with her to do what I can with the horse. Even though it’s only going to be extra work for me, what with haymaking under way and everything else going full pelt in the middle of July, I still consider this a windfall. I’m looking forward to seeing something of Kabara on a regular basis. And anyway, the days are long.