Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Allen & Unwin

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

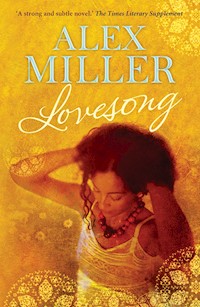

Winner of the 2011 Christina Stead Prize for Fiction Winner of The Age Book of the Year Winner of thePeople's Choice Award at the NSW Premier's Literary Awards Strangers did not, as a rule, find their way to Chez Dom, a small, rundown Tunisian café on Paris's distant fringes run by the widow Houria and her young niece, Sabiha. But when one day a lost Australian tourist, John Patterner, seeks shelter in the cafe from a sudden Parisian rainstorm, a love story starts to unfold. John and Sabiha's becomes a contented but unlikely marriage-a marriage of two cultures lived in a third-and yet because they are essentially foreigners to each other, their love story sets in train an irrevocable course of tragic events. Years later, living a small, quiet life in suburban Melbourne, what happened to them in Paris seems like a distant, troubling dream to John. He confides the story behind their seemingly ordinary lives to Ken, an ageing, melancholic writer who sees in his neighbours the possibility of one last simple love story. Told with Miller's distinctive clarity, intelligence and compassion, Lovesong is a pitch-perfect novel, a tender and enthralling story about the intimate lives of ordinary people. Like the truly great novelist he is, Miller locates the heart of his story in the moral frailties and secret passions of his all-too-human characters.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 380

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2017

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

ALEX MILLER

Lovesong

First published in 2009

This edition published in 2010

Copyright © Alex Miller 2009

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. The Australian Copyright Act 1968 (the Act) allows a maximum of one chapter or 10 per cent of this book, whichever is the greater, to be photocopied by any educational institution for its educational purposes provided that the educational institution (or body that administers it) has given a remuneration notice to Copyright Agency Limited (CAL) under the Act.

This project has been assisted by the Commonwealth Government through the Australia Council, its arts funding and advisory board.

Allen & Unwin 83 Alexander Street Crows Nest NSW 2065 Australia Phone: (61 2) 8425 0100 Fax: (61 2) 9906 2218 Email: [email protected] Web: www.allenandunwin.com/uk

Cataloguing-in-Publication details are available from the National Library of Australiawww.librariesaustralia.nla.gov.au

ISBN 978 1 74237 366 9

E-book ISBN 978 1 92557 537 8

Text design by Emily O’Neill Set in 11.7/17.2 pt Adobe Garamond Pro by Bookhouse, Sydney Printed in Australia by McPherson’s Printing Group

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

For Stephanie and for our children Ross and Kate

I adjure you, O daughters of Jerusalem, by the gazelles or the wild does: do not stir up or awaken love until it is ready!

THE SONG OF SOLOMON

Contents

One

Two

Three

Four

Five

Six

Acknowledgments

One

When we first came to live in this area in the seventies there was a drycleaners next door to the bottle shop. The drycleaners was run by a Maltese couple, Andrea and Tumas Galasso. My wife and I got to know them well. A few years ago the Galassos closed up. There was no explanation for why they had closed, no notice on the door regretting the inconvenience to customers, nothing to reassure us that the business was to open again soon. The premises that had been the drycleaners for all those years remained abandoned for a very long time, junk mail and unpaid bills piling up inside the front door.

I live with my daughter. She’s thirty-eight. She came to stay with me when her marriage broke up. It was to be for a week or two, until she sorted herself out. That was five years ago. I was in Venice during this last Australian winter and came home to an empty refrigerator. I don’t know why Clare doesn’t buy food, she is a very successful designer and has plenty of money, so it’s not that. When I ask her why she doesn’t buy food, she says she does. But she doesn’t. Where is it? I took a taxi from the airport and I walked into my house and there was no milk in the refrigerator. I was exhausted from the interminable flight from Venice and I probably said something harsh to her. Clare cries more readily even than her mother used to. I said I was sorry, and so she cried some more. ‘Oh, that’s all right, Dad. I know you didn’t mean it.’ I don’t understand her.

Even with our enormous modern airliners, Venice is still a world away from Melbourne. You have to adjust. Venice and Melbourne are not on the same planet. No matter how fast our airliners go, or how comfortable and entertaining they become to ride in, Venice will never be any closer to Melbourne than it was at the time of the Doges. It was spring here and everything seemed very dry and barren to me. I’d come home to an empty refrigerator. That’s what I remember. I couldn’t even make myself a cup of tea. So two minutes after I got out of the taxi from the airport I was walking to the shops.

When I turned the corner by the bottle shop, I hadn’t yet decided whether I was glad to be home or was regretting not staying on in Venice for another month or two. Or for a year or two. Or forever. Why not? I was passing the shop where the drycleaners had once been and was asking myself gloomily why I’d bothered to come home, when the delicious smell of pastry fresh from the oven hit me. For twenty years we’d walked past the Galassos’ on our way to the shops and there was the smell of dry-cleaning chemicals. I stopped and stood looking in through the open door of the shop. It was new. I suppose I was smiling. It was such a lovely surprise. The woman behind the counter caught my eye and smiled back at me, as if it made her happy to see a stranger standing out in the street admiring her lovely shop. It was Saturday morning; the shop was full of customers and she was busy, so it was the briefest of acknowledgments that passed between us. But all the same her smile gave my spirits a lift and I went on along the street feeling glad I’d come home and hadn’t stayed in Venice for the rest of my life.

Venice brings out the melancholy in me, inducing the overriding conviction that effort is pointless. Doesn’t it do that to everybody? I walk around in that timeless city feeling like the untouchable Victor Maskell. Which I don’t actually mind all that much. I’ve always enjoyed indulging my gloom. Don’t ask me why. It’s probably my father’s side of the family that does it, the dour Scottish influence, so I’ve been told. I’ve never visited Scotland. As I searched the aisles of the supermarket that dry spring morning, my gloom had vanished and I felt as if I’d been welcomed home by the smile of the beautiful and rather exotic-looking woman in the new pastry shop. While I was trying to remember which aisle things were in at the supermarket I was thinking about the woman’s lovely smile and I probably had a look of secretive pleasure on my face, as if I knew something no one else knew; the kind of look that infuriates me when I see it on someone else’s face.

Sweet pastries were not part of our regular diet, but on my way back from the supermarket I went into the pastry shop. I had to wait quite some time to be served. I didn’t mind waiting. As well as the woman behind the counter there was a man in his late forties and a little girl of no more than five or six years of age. The man and the girl were bringing trays of pastries in from the kitchen at the back of the shop, the man encouraging the girl and pausing every now and then to serve a customer. The mood among the customers was unusually good-humoured. There was none of the regular Saturday morning impatience, no one trying to get served before their turn. Nothing like that. As I stood there enjoying the pastry smells and the friendliness of the place, I felt as if I’d stepped into a generous little haven of old-fashioned goodwill. This, I decided, was due to the family that was running the shop, something to do with the sane modesty of their contentment, but more than anything it was due to the manner and style of the woman.

When my turn came to be served I asked her for half a dozen sesame biscuits. I watched her select the biscuits with the crocodile tongs. Separately and without hurry, she placed each biscuit in the paper bag in her other hand, her grave manner implying that this simple act of serving me deserved all her care. She was in her early forties, perhaps forty-three or -four. She was dark and very beautiful, North African probably. But what impressed me even more than her physical beauty was her self-possession. I was reminded of the refined courtesy once regularly encountered among the Spanish, particularly among the Madrileños, a reserved respect that speaks of a belief in the dignity of humanity; a quality rarely encountered in Madrid these days, and then only among the elderly. It was this woman’s fine sense of courtesy to which the customers in her shop were responding. When she handed me the bag of sesame biscuits I thanked her and she smiled. Before she turned away I saw a sadness in the depths of her dark brown eyes, a hint of some ancient buried sorrow there. And on my way home I began to wonder about her story.

When I was telling Clare about the pastry shop later I said something like, ‘There’s a kind of innocence about those people, don’t you think?’ Clare was sitting at the kitchen table reading the newspaper and eating a third sesame biscuit, taking a little bite from the biscuit and looking at it, then dipping it into her coffee. She had been into the pastry shop several times while I was away, she told me, but had seen nothing especially interesting about it or the people who were running it. ‘He’s a schoolteacher,’ she said, as if this meant they couldn’t possibly be interesting, and went on reading her paper. I added some thought or other about the possibility of a simple love story between them, this Aussie bloke and his exotic bride. Clare didn’t look up from her paper, but said with that quiet conviction of hers, ‘Love’s never simple. You know that, Dad.’ She was right of course. I did know it. Only too well. So did she.

A week or so later I saw the man from the pastry shop in the library. He was with his little girl. Over the following weeks I saw him at the library several times. He was sometimes alone, sitting at one of the tables hunched over a book. There were usually children running around dropping things and making a noise, and I was impressed by the way nothing seemed to distract him from his reading. He read the way young people read, lost to the world around him. Surely, I said to myself—defending my opinion against Clare’s cynicism—surely there is a kind of innocence in the way this man reads? I tried to get a look at the books he was reading but could never quite make out a title. I greeted him on a couple of occasions. But he just gave me a very cool nod. I thought he hadn’t recognised me. He had big hands, the veins prominent. Beautiful hands they were, the hands of a capable man. He seemed more like an artisan than a teacher to me; not a workman but a craftsman of some kind. Perhaps a woodworker. A musical-instrument maker would not have surprised me. I could imagine the harpsichord his hands might lovingly fashion for his beautiful wife.

When he closed his book and got up, he was tall and a little stooped. I watched him going out of the library, his books under his arm, his gaze on the ground ahead of him, and I wondered what had brought him together with his darkly exotic wife.

One warm Sunday afternoon in October, when the weather was more like summer than spring, I met him at our open-air public baths. For several lengths of the pool I’d been aware of another swimmer keeping pace with me in the next lane, doing the crawl as I was, arms lifting and driving down as my arms lifted in turn and drove down into the water. I completed my twenty lengths and stood up at the shallow end. I was resting my back against the edge of the pool and taking my goggles off when the man who’d been swimming in the lane beside me also stood up. I saw at once it was the man from the pastry shop. I wasn’t going to say anything, as he’d seemed quite determined not to recognise me. So I was surprised when he said g’day and asked me if I was a regular swimmer. I said I was hoping to become one. I was glad he was being friendly but I did wonder what had changed his mind about me.

That’s how John Patterner and I met. Side-by-side swimmers. After our swim he invited me to have a coffee with him in the pool café. While we drank our coffee we watched his daughter having her swimming lesson with two of her friends from her prep class. She kept calling out to him, ‘Watch me, Daddy!’ and he kept calling back, ‘I am watching you, darling.’ I said, ‘She’s very beautiful.’ His eyes shone with his pride and love and I remembered how Clare and I had been when she was that age, how infinitely close we had been in those days, how filled with emotion and love and delicacy our friendship had been. And I saw all this again in John Patterner and his daughter. Her name, he told me, was Houria. When he introduced her she looked at me gravely, and I saw she had her mother’s eyes. I don’t remember what John and I talked about that day, but I do remember that the coffee, in its cardboard cups, had somehow managed to become flavoured with the taste of the pool water. Two weeks later I saw him at the library on his own and suggested we have a coffee at the Paradiso. He seemed pleased to see me.

After that we met for coffee every week or two at the Paradiso. Slowly at first, hesitantly, little by little, he began to tell me their story. The story of himself and his wife, Sabiha, the beautiful woman from Tunisia whom he had married in Paris when he was a young man and she was little more than a girl. And the beautiful and terrible story of their little daughter Houria. They lived now in the two or three rooms above the pastry shop. There couldn’t have been a lot of space for them up there. Their family kitchen was the kitchen on the ground floor behind the shop where Sabiha made her delicious pastries. You could see the kitchen from the street. When I walked past late at night, taking Clare’s kelpie, Stubby, for a last walk for the day, the light in the pastry shop kitchen was usually on.

From the day we’d had our pool-flavoured coffee together at the baths, I had detected his need to talk. But he was a modest and very private man and it took me some time to convince him that his story interested me. Time and again he said to me, ‘I hope I’m not boring you,’ and laughed. It was a laugh that implied all kinds of reservations and uncertainties. This laugh of his made me anxious. I was afraid he might decide he’d revealed too much and say no more. But I was the perfect listener for him. I told him so. I was the best listener he’d ever had or was ever likely to have.

My last novel was always going to be my last novel. I’d had enough. ‘That’s it,’ I said to Clare when I finished the last one. ‘No more novels.’ She asked me what I would do. I said, ‘Retire. People retire. They travel and enjoy themselves and sleep in in the mornings.’ She looked at me sceptically and said, ‘And will you play bowls, Dad?’ I’m her father and she’s entitled to these little witticisms. I was so sure that book was my last I had called it The Farewell. I thought this was a pretty direct hint for reviewers and interviewers, who are always on the lookout for metaphor and meaning in what we do. I waited for the first interviewer to ask me, ‘So, is this your last book then?’ I was ready to say, ‘Yes, it is.’ Simple as that, and have done with it. But no one asked. They asked instead, ‘Is it autobiographical?’ I quoted Lucian Freud: Everything is autobiographical and everything is a portrait. The trouble with this was they took Freud’s radiant little metaphor literally. So I went to Venice to enjoy my solitary gloom for a month or two. When I got home I realised I didn’t know how to do nothing. During my life I had acquired no skills for not working and I soon found that not writing a book was harder than writing one was. How to stop? It was a problem. For a while I concealed my panic by doing things like going to the National Gallery in the middle of the morning during the week. It was pretty demoralising. The place was haunted by do-nothings like myself. I watched them, solitaries all of them. Then I met John Patterner, and suddenly I had something to do. I could listen to him telling me his story. More than anything, I wanted to know by what means sorrow had found its home in the eyes of his beautiful wife. That was what I listened for, to find that out.

If it was fine we took a table on the footpath under the plane trees outside Café Paradiso. John liked to smoke. ‘I’m having a spell at the moment,’ I told him when he insisted he was keeping me from my work. He sat a while, playing with the unlit cigarette between his fingers, then he straightened and began to tell me about himself, the cigarette unlit in his hand until he finished talking and we’d got up and were walking back to the shop together. Only then did he finally light his cigarette. I suppose he was trying to give them up. He told me he was originally from a farming family somewhere up on the south coast of New South Wales. And Clare had been right, he was a schoolteacher these days, teaching English as a second language to boys and girls at the local secondary college, kids who for the most part came from homes where the language spoken was not English, which is about half the population around here. He spoke of his students with great respect, but I had the feeling he was not content in his job. He loved his wife and his daughter, but he also loved to lose himself in a book. I picked him for a passionate reader.

So, to his story then. I soon began to realise that it was, in its way, a confession. But isn’t that what all stories are? Confessions? Aren’t we compelled to tell our stories by our craving for absolution?

Dom Pakos was in his narrow kitchen at the back of the café serving up his usual midweek offering of overcooked pieces of stringy beef from the abattoirs down the road, mixed with a couple of dozen boiled zucchinis and one or two spices, a dish he dignified with the name sfougato. Dom was a man of short stature with a nose that had been broken so often in his youth it looked as if it might have been trodden on by an elephant. Despite the hard bulk of his torso, Dom, at that time in his fiftieth year, was quick and confident in his movements. He was ladling the sfougato into bowls, the big saucepan set on the gas stove in front of him, the bowls laid out in a line on the marble bench to his right. Dom let go of the big iron ladle, which dropped into the saucepan, splashing the front of his white shirt with gravy, and he gave a short gasp, as if he had suddenly remembered an urgent appointment. And with that he collapsed onto the tiles.

The café, Chez Dom, was in the narrow street known in those days as rue des Esclaves, opposite Arnoul Fort’s drapery and next door to André and Simone’s stationers. If you turned left outside the café and walked past the stationers to the corner, then crossed the square and walked down the slope on the far side of the square for a hundred metres or so, you crossed the railway line and came to the source of the nose-tingling smell that pervaded the locality in those days: the great abattoirs of Vaugirard. For the locals, the distinctive smell of the slaughterhouse signified work and home. Some days the smell was sharper than others, and there were days when it was scarcely noticeable at all. Like the weather, the smell was always there, day and night, winter and summer. And, as with most things, familiarity had rendered it innocuous to the people who lived in the area. It was newcomers who wrinkled their noses.

The red checked curtains that Dom’s wife Houria had strung across the lower half of the café’s window were always drawn aside, allowing the daylight to enter the modest dining room and permitting the patrons to see who was coming and going on the street outside. Inside, a plain varnished timber bar stood across from the front door, and here Houria dealt with the bread and the wine and the coffee. The wooden trims around the window and door were painted green, and the walls were a calm faded old pink, rather like the underside of a freshly picked mushroom. Houria always had laundered red or green checked cloths spread over the six tables. And, depending on the time of year, there was usually a generous bunch of yellow daisies or russet chrysanthemums in a green ceramic jug at the end of the bar nearest the door. The only sign advertising the café was painted in a less than professional hand in red letters across the window above the door. At the back of the dining room, opposite the door and to the right of the bar, a bead curtain led through to the kitchen, where Dom Pakos did his work. Chez Dom’s customers were from the immediate locality, many of them from the lower levels of management at the abattoirs. It was rare that a customer enjoying a midday meal in the little dining room did not know all the other diners. Strangers did not, as a rule, find their way to Chez Dom.

The café had been established twenty years earlier by Dom Pakos and his Tunisian wife, during the winter of 1946, in those chaotic days immediately after the war, when everyone was scrambling to find their feet. Dom Pakos had been a merchant seaman before the war and a ship’s cook during the war and had found himself stranded in Paris when the peace was signed. It was meeting Houria, who was twenty-eight at the time, that decided Dom to give café life a try. He was always to claim afterwards, with a combination of surprise and pride, that it was Houria who had made sense of his life for him. They were both misfits the day they met, and each knew at once, with a fierce instinct, that they would cleave to the other for life. Neither ever required children from their union to make it complete. Dom and Houria completed each other.

Dom thought he was a great cook, but he was not even a middling to good one. The café thrived not on Dom’s cooking but because he was an energetic and cheerful man who enjoyed the company of his customers. For Dom Pakos all people were pretty much equal; the good, the bad, the ugly and the beautiful, the old and the young, the infirm and the agile, they were all much of a muchness to Dom. He had sailed to the wildest ports of the world and seen everything of the human parade on offer. If you were even half-human, you felt Dom loved you. And if you were a stray dog or cat, he fed you scraps at the back door of his kitchen, where the defile of the cobbled laneway to this day arrives at its abrupt destination. Dom’s tolerance had its limits, to be sure, but generally he was open to the world and indiscriminate in his affections. He was not a religious man, but neither was he averse to the company of those who were. Dom’s gift was the gift of happiness. He had it from his mother. His ease and generosity of manner could strike a smile from the sourest soul.

It was a pity he died the way he did. Less than two minutes elapsed between Dom’s collapse and Houria’s return to the kitchen from the dining room. She pushed in through the bead curtain, some comment or other ready on her lips, expecting to find the bowls filled and ready for her to carry out to the waiting diners. She saw at once that Dom Pakos was dead. But Houria did not scream or react in any way as if she was witnessing something terrifying. She knelt on the old cracked tiles beside her husband and took his head gently in her hands. ‘Dom!’ she pleaded softly, as if she expected to wake him. She knew he was dead. Death is unmistakable. But she could not believe he was dead. It was the first time she had ever seen a grimace of discontent on her husband’s face, and it was this she remembered afterwards.

When the surgeon conducted a post-mortem on Dom’s corpse two days later at the hospital mortuary he found that an aneurism in the wall of Dom’s abdominal aorta had burst. ‘Dom scarcely suffered at all,’ the surgeon reassured Houria when she went to the hospital to receive his report. The surgeon was tall and had drooping, sad eyes, as if he carried the weight of the world on his shoulders, and a small moustache beneath a large nose. He reminded Houria of the saviour of France’s dignity, Le Général himself. She felt safe with him, and half believed, even as she sat in his office next door to the mortuary, where Dom’s remains were lying, that the surgeon was going to tell her Dom was not dead after all.

‘So he is dead, then?’ she said, the tiny little hope she had kept alive until now winking and going out as she spoke it.

‘Oh yes, Madame Pakos, your husband has passed to the other side, we can have no doubt of that.’ The surgeon smiled and touched his small moustache, which had begun to remind her of Hitler’s moustache. ‘Your husband was a very fit man for his age, Madame Pakos.’

The surgeon said this with such an air of comforting surprise she thought for a flickering instant he was telling her good news. ‘You must have been taking very good care of him. When your man’s aorta burst he exsanguinated in a matter of seconds.’ The surgeon fell silent, deep in thought for a moment, then he suddenly went ‘Whoosh!’, making the sound through his pursed lips and at the same time throwing out his hands towards Houria across his desk in a bursting motion.

Houria jumped.

The surgeon regarded her closely, then announced in a grave voice, ‘Once the gate was open, Madame Pakos, his big heart pumped his blood into his abdominal cavity at a terrifying rate as it struggled heroically to do its job. But to no avail.’ He paused and drew breath, then leaned towards Houria, conspiratorial in his intensity. ‘When the body’s Canal Grande bursts its banks, the more powerful the heart the more abrupt the decease of the man.’ He sat back. His expression indicated to Houria that something greatly to his satisfaction had just been expressed and she wondered if she should offer him some kind of congratulation. But the interview was over. The surgeon had other fish to fry.

Her interview with the surgeon signified for Houria the official end of twenty years of happiness with Dom Pakos. She was forty-seven and from now on she was to be alone. She thanked the surgeon and got up from her chair and went home to the café, which was very silent and very still. A lonely empty place without her Dom.

She sat on their bed in their room above the café and stared out the window at the upstairs windows of Arnoul Fort’s shop across the street. She had not taken off her coat and she still clutched her bag in her lap with both hands, as if she was expecting to be called at any minute to get up and go somewhere urgently. But the minutes went by and no one called. The voices of children playing in the street beneath her window, cars hooting their horns, and every now and then a voice raised in greeting or farewell, the tight, sharp smell of the abattoirs. This was her home. She would have liked to reach back into the antique past and have her own grieving voice joined in lamentation with the voices of the women of the tribe. But all that was lost to her long ago. After staring out the window for quite a long time, Houria suddenly remembered that Dom was never coming home again. She began to sob helplessly, the wrenching pain of his loss like an iron band around her chest.

When she at last stopped weeping, she got off the bed and went downstairs and hung her coat in the alcove and put her bag on the bench in the kitchen. She made a glass of sweet mint tea, clasping it in both hands close under her nose to comfort herself with its familiar fragrance. She could see Dom’s shadow through the bead curtain. He was standing by a table in the dining room looking out the window, gesturing with his cloth in his hand, talking to a customer. He was so real she could have reached out and touched him. ‘Dom!’ she whispered, the emptiness of despair in her now. ‘Do you remember, you promised you would always love me and would never leave me?’

She closed the café and put a notice on the door, and for several days she went about aimlessly, picking up a saucepan then putting it down again, going to the back door and looking along the lane, not knowing what to do with herself. She cried a good deal and was not able to settle to anything. André’s grey ghost of a dog, Tolstoy, a big old borzoi, came to the back door and pressed its head against her and gazed up at her with its great melancholy eyes. She caressed the head of the beautiful beast and it stood close and attentive while she told it of her sorrow, the faint sour animal smell of its damp pelt rising pleasantly to her nostrils.

One evening, when the children on the street had all gone home and the cars had ceased going by hooting their horns, she sat in the absorbed silence of the little sitting room they had made together under the stairs and she wrote a letter to her brother in El Djem. An unaccustomed longing for home and family had risen in her as the evening had come on, like the waters of a long-dry spring returning and bubbling to the surface.

Dearest Hakim, she wrote. My man is dead and now I am alone. I have decided to come home, but first I must put our affairs in order here and sell the business if I can find a buyer for it. The freehold is not ours but André, our landlord, is a good man and will give me time to do the best I can for myself.

She wrote some more about herself, then asked how everyone was at home, struggling all the while to form a clear picture in her mind of the place she had not seen since she left it with her mother as a girl of seventeen, thirty years earlier.

In El Djem a few days later Houria’s brother, Hakim, came home from his day’s work on the road gang. His wife took his jacket at the door and his two unmarried daughters, Sabiha and Zahira, stood beside her looking at him. Hakim’s moustache was whitened from the dust of the road. His wife handed him his reading glasses and the letter and he stood angling the envelope to the light in the doorway, examining the writing. Hakim opened the envelope by running the disfigured nail of his thumb under the flap and he took out the single sheet of paper and unfolded it. He read his sister’s letter aloud to them, reading slowly, pronouncing each word with care, lingering in a small silence at the end of each phrase. Hakim had lost his government job when he joined the Communist Party, but he had not lost his ideals or his self-respect. When he finished reading his sister’s letter he looked up at his wife and daughters. ‘Dom Pakos is dead,’ he said, surveying their faces. He had never met his sister’s husband. ‘My sister is coming home.’

Hakim washed, then went out into the courtyard and sat on the bench under the pomegranate tree and smoked a cigarette in the last of the sun, the ruined amphitheatre visible above the wall of the courtyard, its ancient stones golden in the evening light. His wife brought him a glass of mint tea and he thanked her. She withdrew into the house to prepare the evening meal and he sat in the quiet alone, sipping his tea with little slurping noises and taking an occasional drag on his cigarette. He had read the despair in his sister’s words and her pain had touched him. They had not seen each other for thirty years. He decided to send his youngest daughter, Sabiha, to Paris to keep Houria company and help her until Houria could sell her business and organise her move back to El Djem. He could not bear the thought of his sister grieving alone in the distant city of her exile. Even as this decision was forming in Hakim’s mind, he was thinking how patterns form in families, repeating themselves like patterns in the weave of a carpet, from one generation to the next. He was thinking of Houria leaving on the bus with his mother all those years ago, he and his father and two brothers standing by as the bus pulled away from the post office, his sister’s and his mother’s faces pressed to the window, their hands waving. He was not yet a man then and had never understood why his mother had gone away, but had accepted it.

Sabiha came out of the house. She was the favourite of his two daughters. She stepped across to him and took her aunt’s letter from the bench beside him where he had laid it. He watched her read it, seeing the eagerness in her. The Difficult One, he called her. Two daughters, and on this one destiny had placed its mark. Why this should be so, no one could know, but he had known from the day of her birth that she was not to be as his other daughter was. He and Sabiha understood each other in ways neither of them could explain. He knew Sabiha would manage Houria’s grief, and would even manage the whole of Paris, and the world, if she was called upon to do so. What is it, he asked himself, looking with love at his beautiful daughter reading the letter, that makes some people so different from others that they cannot share a common fortune with them?

Sabiha sat on the narrow bench beside her father and leaned her head against his shoulder. ‘Do you miss your sister?’ she asked him. She was dreaming of her aunt Houria in Paris. She longed to meet her aunt and to know Paris.

Since Dom’s death Houria had been worrying about her hair. Dom had liked her to keep her hair long, so that she could uncoil it in front of the dressing-table mirror at night and brush it out while he lay in bed admiring her. ‘Long hair,’ he told her, reaching his arm around her as she climbed naked into the bed beside him, ‘is the true grace of a woman.’ They slept naked. Winter and summer. As long as Dom was alive there had never been a chance of even talking about getting her hair cut short. But Houria had been secretly envying women with short hair for some time.

While no one, and certainly not Houria herself, would have come straight out and said that Dom’s death was a blessing in disguise for Houria, his absence did nevertheless bring certain liberties into her days. There were even odd moments when she caught herself guiltily enjoying being without him, the thought teasing her that she was entering a new and interesting phase of her life. She had begun letting the grey grow out, but that was all, so far. It was a start. She was not standing still. She saw women of her own age, and even older, going about the streets with fashionably short grey hair and she envied them. It wasn’t so much that they looked smarter, though they did, as that they seemed to her to be freer and more confident. As if they were living in a world of their own choosing. Their own world, that’s what she envied these women. Something to do with a decision they had made. Their step was lighter, she noticed, than the step of older women like herself who still wore their hair long and had the grey disguised by the hairdresser every few weeks. Now that Dom was gone, she was impatient to join the shorthaired women of Paris before it was too late to enjoy it. She was agonising now over whether Dom had been dead long enough yet for her to get her hair cut short without offering a slight to the dignity of his memory. If she were to suddenly appear on the street and in the café with short hair, mightn’t it seem to everyone that she was glad to be rid of him? Mightn’t it even seem like that to herself? This possibility was all that was holding her back.

She was standing in the doorway between the kitchen and the dining room, holding the bead curtain aside and watching Sabiha lay the tables. Sabiha was wearing a pretty blue and white dress with a belted waist. Her long dark hair was tied back with a blue ribbon. When Sabiha straightened and turned around, Houria said, ‘How do you think I’d look with short hair, darling?’

Sabiha considered her aunt, holding the bunch of knives and forks and the cloth in her hands, seeing a woman nearing fifty, her thick coil of hair growing out at the roots into a strong iron grey. ‘Really short? Or just shorter?’ she asked. Houria had a broad, handsome face, her hair pinned in a double coil and sitting like a cowpat on top of her head. It looked very unnatural and heavy. And it made her aunt look like an old woman. Like a woman who had given up trying, or who was maybe trying too hard. When Houria had complained to her of getting old, Sabiha told her, ‘You don’t seem old to me. You seem really young for someone your age.’ Houria had laughed and hugged her.

‘No, really short,’ Houria said, reaching her hands up and pushing at the heavy cowpat with her fingers, dusting her hair with flour—for she was in the middle of making a batch of filo. ‘Down to an inch or two.’ She held up her hand, thumb and forefinger indicating the length of hair she was aiming for. ‘Two, maybe three at the most. What do you think? Tell me the truth.’ She was longing to get out from under her hair. If Sabiha approved, she would step into the hairdressers this afternoon and have it done. Sabiha herself had beautiful hair, long and glossy and black as . . . well, very black. It would be a terrible pity if Sabiha were to cut her hair short. But that was not the point. Sabiha was twenty-one and would soon have to find herself a husband and start a family. At Sabiha’s age, long hair was as much a necessity of life for a woman as a moustache was for any half-decent sort of man. There was a time for everything.

Sabiha smiled. Her aunt stood before her in her enormous blue apron and those heavy black shoes she always wore. Houria was not a beautiful woman. In fact she was short and fat. She was a lovely woman. But she was not beautiful. Those vast breasts and her strong arms and sturdy legs could not be called beautiful. A good and capable woman she was, to be sure, and kind and generous. All those things. She was surprised now by her aunt’s vanity. Sabiha’s own mother was not vain. Or at least Sabiha had never noticed her mother being vain, not about her appearance at any rate. Her mother was delicate, thoughtful and intensely proud of her husband, but she was not vain. Sabiha tried to think of her mother with short hair but couldn’t imagine it. Houria was very different from her mother. Sabiha’s mother was beautiful. She was sad and beautiful and she had wept when Sabiha left on the bus from outside the post office. Her father had definitely not married his sister’s look-alike. It amused Sabiha to see this anxiety in Houria about her appearance. ‘Why don’t you just go and get it cut,’ she said. ‘If you don’t like it, you can let it grow again.’

Houria patted her hair. ‘Do you really think I should?’ She knew in her heart that to cut her hair short now would be a kind of divorce from Dom. She wanted a divorce from him, was that it? She wanted a divorce from their past. That was it. To hope for something good in her future, that was what she wanted now. To set out again. With his death, if she was not to begin living in the past, divorce from the old days with Dom was a necessity. It was very unexpected and she did not quite know what to make of herself for thinking in this way. Was it good or bad? She was not sure. But it excited her and she could not help secretly admiring herself for it. She understood there was a kind of courage in it.

‘It will grow again,’ Sabiha said lightly, setting down the knives and forks again on the red checked cloths. ‘Just get it cut if you want to. I would.’

‘Would you really?’ This wasn’t the answer Houria had been hoping for. She wanted enthusiasm from her niece. She said glumly, ‘Dom liked it long.’

Sabiha paused again and they stood looking at each other across the small dining room.

Sabiha wanted to say, Listen, Dom’s dead. Okay? So just get your hair cut if you want to. What’s the difference? She smiled and said nothing. She had never met Dom of course. And there was evidently a complication she did not understand. People were funny. She loved her aunt and didn’t want to say anything that might offend her.

Houria lifted her shoulders. ‘I just don’t know what to do!’

The very first evening Sabiha arrived in Paris, they were standing in the back room upstairs that Houria had prepared for her. It was a sweet little room, under the sloping roof, intimate, safe and homely. A bed with a flowered cover and a hard-backed chair beside the bed, an old black trunk from Dom’s seafaring days pushed up under the slope of the roof to keep her clothes in. A pot of some lovely fragrant spice mixture on the deep windowsill, like a blessing on the air. Sabiha felt she was wanted. Houria apologised for the lack of a mirror.

‘I’ll get you a mirror, darling, as soon as I have a minute.’ She asked her then if there was something special she wanted to do in Paris.

Sabiha said, ‘I’ve imagined going up the Eiffel Tower and seeing the whole of Paris laid out below me.’

Houria leaned and pointed through the single-paned window above the bed. ‘See that red light? Way over to the north of us there?’ Sabiha bent to look and their heads touched. ‘That’s the light on the top of the Eiffel Tower.’ They leaned there together, looking out the narrow window into the glowing sky above the great city.

Sabiha said, ‘It’s so beautiful.’ And it was, for there is no more beautiful sight in the whole world than the rooftops of Paris at night.