Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Allen & Unwin

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

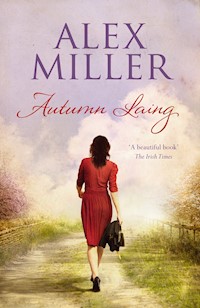

Autumn Laing seduces Pat Donlon with her lust for life and art. In doing so she not only compromises the trusting love she has with her husband, Arthur, she also steals the future from Pat's young and beautiful wife, Edith, and their unborn child. Fifty-three years later, cantankerous, engaging, unrestrainable 85-year-old Autumn is shocked to find within herself a powerful need for redemption. As she tells her story, she writes, 'They are all dead and I am old and skeleton-gaunt. This is where it began...' Written with compassion and intelligence, this energetic, funny and wise novel peels back the layers of storytelling and asks what truth has to do with it. Autumn Laing is an unflinchingly intimate portrait of a woman and her time - she is unforgettable.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 701

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2017

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Autumn Laing

ALEX MILLER

This is a work of fiction. All characters and events have evolved from the author’s imagination.

First published in 2011 This edition first published in 2012

Copyright © Alex Miller 2011

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. The Australian Copyright Act 1968 (the Act) allows a maximum of one chapter or 10 per cent of this book, whichever is the greater, to be photocopied by any educational institution for its educational purposes provided that the educational institution (or body that administers it) has given a remuneration notice to Copyright Agency Limited (CAL) under the Act.

Allen & Unwin Sydney, Melbourne, Auckland, London

83 Alexander Street Crows Nest NSW 2065 Australia Phone: (61 2) 8425 0100 Email: [email protected] Web: www.allenandunwin.com/uk

Cataloguing-in-Publication details are available from the National Library of Australiawww.trove.nla.gov.au

ISBN 978 1 74331 113 4

E-book ISBN 978 1 92557 531 6

‘Autumn Day’, translated by Stephen Mitchell, copyright © 1982 by Stephen Mitchell, from The Selected Poetry of Rainer Maria Rilke by Rainer Maria Rilke, translated by Stephen Mitchell. Used by permission of Random House, Inc.

The quotation from Leichhardt’s Journal is from the Corkwood Press facsimile edition of Ludwig Leichhardt’s Journal of an Overland Expedition in Australia, 1996, p. 188.

The quotation is from Canto 1 of Dante’sParadiso, translated by John D. Sinclair, revised edition, John Lane, 1948.

Cover design: Lisa White Front cover photograph: Nathalie Savey/Millennium Images Illustrations: Maria Sibylla Merian Typeset by Bookhouse, Sydney

PATRICK WHITE: I would like to write a novel about her.

BARRETT REID: About Sunday? Have you ever met her?

PATRICK WHITE: That woman! That woman! I don’tneed to meet her to write about her.

DAVID MARR, Patrick White: A Life

ALSO BY ALEX MILLER

Lovesong

Landscape of Farewell

Prochownik’s Dream

Journey to the Stone Country

Conditions of Faith

The Sitters

The Ancestor Game

The Tivington Nott

Watching the Climbers on the Mountain

For Stephanieand for our son Ross and our daughter Kateand for Erin

Contents

Part one

1 New Year’s Day 1991

2 Edith Black, 1938

3 Pat Donlon

4 March 1991

5 Edith’s announcement

6 July 1991

7 The big picture

8 Arthur

Part two

9 September 1991

10 Once, if I remember well . . .

11 November 1991

12 Picnic at Ocean Grove

13 November 1991

14 The flies

Part three

15 Retribution

16 5 December 1991

17 Paradise garden

18 28 December 1991

Editor’s note

Acknowledgments

How I Came to Write Autumn Laing

PARTone

1New Year’s Day 1991

THEY ARE ALL DEAD, AND I AM OLD AND SKELETON-GAUNT. THIS is where it began fifty-three years ago. Here, where I’m standing in the shadows of the old coach house, the boards sprung and gaping, this stifling January afternoon. I was thirty-two. I’ve retreated from the sun and smoke. The smell of smouldering paper has followed me. Blue smoke in the sunblades cutting the interior dark into shapes—in imitation of the work of a certain painter we once admired. There are things concealed and covered up here. The abode of the dead I should call it. In the shade, where I belong. Don’t laugh. It’s an old anxiety with me, this impulse to probe the rubbish with the toe of my sandal, disturbing the litter in the hope (or dread) of turning something up. I’m no longer a woman. Oh, you’ll understand all that soon enough. The buckle on my left sandal broke last night when I was dragging my mattress onto the veranda to catch the breeze. Instead of the breeze I caught my foot against the back step. I’ve no strength left in my legs. My legs! Back in my smooth skin days I seduced him with glimpses of the purity of my pearly thighs, watching him ache for my touch, my insides churning. There was no stopping us then.

I saw her on the street yesterday. And last night I was sleepless thinking about her. The air burning in my lungs at two this morning. I thought of going down to the river bank and lying on the grass under the silver wattles for a bit of relief. But I can’t manage it any more. I haven’t been to the river for it must be fifteen years. If I could reach the river bank I would lie there naked as I lay with him. My body white and still and cold in the moonlight now. On my back (ready for it, Pat would have said), my life and their lives seething in my brain. His and hers. I’m little more than a skeleton these days. No, it is funny. I won’t have it any other way. You can laugh all you like. I’ve never begrudged anyone a laugh. God knows, we get few enough of them.

Until I saw Edith yesterday I was ready to become that white corpse on the river bank. It’s true, I wanted it. I have the means for my end tucked away in the back of the drawer of my bedside table. But instead of dying last night I repaired my broken sandal with the length of purple silk ribbon which was around the box of cheap chocolates given me by that cheap woman who called here yesterday. If it was yesterday. And was it after I’d seen Edith or before I saw her? It doesn’t matter. She—the woman with the chocolates, I mean, not Edith—parked her car by the front door then walked around the side, coming through the rhododendrons to the back door as if she was one of our old group. She surprised me with my nightdress up around my middle at three in the afternoon, doing my corns. I should get a big dog. Or a gun. She stood with one foot on the raised course of bricks at the edge of the fish pond (no fish) and smiled up at me, her cheap offering held towards me. Wearing immaculate white linen she was. Her fat features glistening with the heat. Her fat body made for rolling down the hill into the river. That’s what I thought as I looked at her.

‘Who are you?’ I asked. I wish I could have menaced her but there was nothing to hand. I couldn’t stand up at once but I did pull my nightdress down over my ghastly shanks. Why are they always bruised? The bitch had given me no chance to conceal myself, to gather my dignity and hauteur. The truth of my decay was in her face. The ugliness of me. Her black eyes eating it all up. Writing my end. That was her cunning, to catch my lowest truth in the first moment without having to struggle for it. To arrive at Autumn Laing without preliminaries. She has the ruthlessness of a scavenger, and the luck. I know them, the scavengers. They feed off our flesh before we’re dead. What is privacy to them?

‘I’m the one who’s writing your biography,’ she said. Cheerful as a bee. Breathless with self-esteem. Fat as a turd, Pat would have said.

‘You’re after something more than my story,’ I told her. I can be fierce. ‘I’ve nothing to say to you. Get out of here.’

She came up the step and helped me to my feet, offering her cheap offering. I’m a foot taller than she is but I couldn’t shake her off. She clung. ‘You’re after one of his drawings if you can lay your eyes on a loose piece about the place.’ She had the confidence to laugh at this insult. She was as steady as a bollard. The peculiar smell of her. The chocolate box pressing into my ribs.

The mess of paper and rubbish here. There must be dozens of his drawings. Hundreds of them. I used to think I’d organise it all one day. Employ a young helper. Restore this house to something like a state of good order. When I was young I prided myself on being a good housekeeper. I imagined our papers boxed and numbered, ready to be carted off to the archives of the National Library. Then they could cart off my cadaver to the cemetery. I saw the end, my own, as neat and orderly. I always said I’d go when I was ready. But I’m less certain of that now. I have my pills but a gust of panic could knock me flat at any time and render me incapable. That’s the fear.

The scavenger bitch biographer stopped me in the hall, her hand to my arm. To draw my attention to the exquisite blue of the Sèvres tureen on the hallstand, she said, where the sunlight was catching it just at that moment. As if I wouldn’t have noticed. It was a ploy to convince me she has an eye, to let me know she is cultivated. But she is without respect. Without insight. I’ll bet she didn’t notice the crack in the tureen. It was Pat himself reeled against the stand, drunk or in despair. I should have given it to her. Here! Take it! A going away and staying away present.

They are all gone. Every one of them. Except Edith, his first. The laughter (I almost wrote slaughter) and passion are spent. Seeing Edith in the street shocked me. To know she still lives left me helpless. I had to sit on the bench outside the chemist’s shop. The chemist’s girl came out and asked me if I was all right. ‘I can give you a lift home, if you like, Mrs Laing.’ I told her I was all right. They only want to help. It’s not their fault they’re stupid.

Lying sleepless in the sleep-out last night (if it really was only last night and not weeks or months ago. Or was I on the veranda?) waiting for the dawn, Edith’s presence was before me like an imperishable icon. I’m not sure why I write that. Except that it’s the truth. The way it felt. The persistence of her vision almost religious. An apparition fattened by my unshriven guilt. Let me shrive me clean, and die, Tennyson said. None of us willingly dies unclean. Religious or not, to seek confession and absolution is an essential moral imperative of the human conscience, isn’t it? To absolve means to set free, and that is what we yearn for, freedom. Young or old, it’s what we dream of and fight for. We never really know what we mean by it.

By the time the freeway (now there’s un-freedom for you) was waking up I knew I wasn’t going to enjoy an untroubled death after all. Problem-free, with a silly grin on my stiffened features when the bitch scavenger found me. Seeing Edith after all these years snatched the prospect of my own orderly death out of my hands. If Edith Black was not done with life then I was not done with it. The question that refused to let me sleep was whether I might yet recompense her with the truth. To embark on the confession that he and I resisted for so long. That he resisted. Most of all, the confession he resisted. It was his truth, after all, that he denied to us. And in denying it to us denied it to himself. I was humiliated and left with nothing. But the largest burden of our cruelty surely fell on Edith, abandoned and alone with her child. The form of Pat’s cruelty was always in his denial of things that made him uncomfortable. Even in that great expansive art of his, encompassing our entire continent, a truth was denied, was kept to one side of the picture, in the silence. And it was great. His art, I mean. There was none greater before him and there have been none greater since. Not in this country. My poor sad country. This vast pile of rubble, as someone has called it, that we think so very highly of (it is all we have to think highly of). My soul was in his vision before he ever knew his vision’s force. I gave it to him. I opened him to it. His country and my own. I and he together made this country visible. To make my claim on his art and compose the testament of our truth. A testament without which his pictures must remain forever incomplete. Forever mute. Deaf and dumb to the posterity they inhabit. The posterity of Edith and her child. Without my witness, Pat’s claim that his art represented an inner history of his country and his life is just another deceit in the veil of deceits with which he artfully concealed his truth. A sleight of hand he became so adept at he fooled himself with it in the end. Who can say under which cup Pat Donlon placed his truth?

Pat was never deep. He was intuitive, but he was not deep. It was I who was deep. I who was left on my own to struggle with the fearful knots and tangles of our vicious web, while he sailed on in clean air, free of self-doubt, painting his pictures as if they were his alone to paint. So instead of eating my three little yellow pills I shall write this. Then I shall eat them.

Did I say I was on my own these days? I still have Sheridan, of course (my sweet Sherry). He will be eighteen this year and in the life of cats is even older than I am in the life of humans. Barnaby was the last of our company of human friends. Poor silly old Barnaby in the end. His blackthorn shillelagh is leaning in the corner by the door where he left it. Now there is no one for me to bully. He gave in at the beginning of summer to his persisting irritation with life. How I resent that! It was so selfish of him. How could he? Didn’t he think of me carrying my pot of tea out to the back veranda and having no one to gossip with but Sheridan? When there are no other humans, a cat, even loved as I love my darling Sherry, is not sufficient company. Barnaby taking his own life, as if (and I enjoy the repetition) it were his alone to take. The handful of it that remained to both of us. Going off in that sad little way with his head in a plastic bag, like something from the supermarket. An old man should have acquired more dignity. But what am I saying, Barnaby was never old. Nor dignified. His motto surely was, You have the dignity, I’ll have the fun. Until his parents died and the station was sold he left us each year for a month or two to revisit his birthplace and his friend in the Central Highlands of Queensland. His home was a cattle station with the lovely name of Sofia, deep in the mountains they call the home of the rivers. ‘I go to refresh my source,’ he said. ‘Don’t worry, I’ll write.’ And he did. He was always urging us to visit him there. When I at last went there with him and Pat, the visit changed all our lives. But you will hear more of that later.

If you knew Barnaby Green, the beloved poet laureate of our circle, you knew even in his decay a youthful man. There was nothing Barnaby could do to temper that out-of-time youthfulness of his. Whenever he ventured a patrician gesture he became laughable, poor man. Those who did not know him and love him as I knew him and loved him thought him a snob. I would not have predicted his suicide. He surprised me. Dismayed me. Angered me. His suicide made me feel as if I had never really known him. I felt cheated. Betrayed. Yes, I felt that in killing himself Barnaby betrayed me. Had he kept himself from me after all? His inner self? Barnaby’s suicide, almost as much as seeing Edith in the street the other day (or whenever it was) shook my certainties about myself. That is what has happened. These things are not easy to understand. And you no longer expect it at my age. To have your certainties contradicted by experience, I mean.

I might have been prepared for some gesture of that heroic kind from the others. Their deaths were not surprising but confirmed the lives they had lived. Barnaby’s left me wondering. About myself. And then Edith appears. As if a last dream has waited its awful moment to come upon me and make its terrible demand.

Since seeing Edith my memory has become the cathedral of my torment. Well then, I shall consecrate its old stones to my truth. Am I being grandiose? Melodramatic? I am old-fashioned and am not going to try to be modern. My truth, did I say? It was his truth too. Not Barnaby’s, Pat’s. Did Barnaby even have a truth? A man of such powdery illusions, such primal gaiety? I doubt if the gravitas of truth ever stuck to Barnaby for long enough to become his own. Pat Donlon’s truth, I mean. His. Let me be clear. It is Pat, our greatest artist, if it is art that renews our vision of ourselves and our country, of whom I wish to speak here. And of myself. The torture that accompanies grand visions. That, and the beauty and the awful price of illicit love. The torture of seeing what others have yet to see. The torture of knowing what has been kept hidden, unseen, in the silence and the dark of wilful denial. All that. The suffering and the transcendent bliss. All right, yes, I am being grandiose. I like the sound of it!

I was christened Gabrielle Louise Ballard. From the beginning I hated my name. I refused to answer to Gabrielle and was teased to tears by my brothers with Gabby. When my darling Uncle Mathew came to visit and found me alone in the garden weeping, he took me on his knees and caressed my burning cheeks with his lips and called me his sweet golden Autumn. That is not a moment I shall forget. It goes with me into my grave—like the golden amulet of an Egyptian princess. Autumn is the name I have been known by all my life. No friend ever called me anything else. Freddy reduced me to Aught, of course. But I loved Freddy and forgave him. Gave him, indeed, the liberty of his dreams with me. But with Freddy it was always a game. Life. Nothing more.

It is the first of January, 1991. My first New Year’s Day alone. I was born in 1906. So I must be eighty-five. Is that right? Some people still have vigour at eighty-five. Barnaby had the facade of it. Close to, however, one saw the vacant sky behind his windows. But I have obeyed the biblical laws and become a disfigured crone. Still tall, I am stooped and cranky and thin as . . . Well, as thin as something. Think of something yourself. My scalp is dry, with reddened patches visible through the stray wisps of silver hair that remain attached. Colourless, really, rather than silver. This is my last chance to tell the truth. I must remember that. Which is why I wear a scarf. Because of my hair, I mean, not because it’s nearly impossible to stick to the truth. Not like the Queen’s scarves, but more a scarf of the kind once affected by America’s beat poets and the pirates. Tight to the skull. I have a long skull. Even with my stoop, once dressed and in public my appearance is tall and haughty. Today my headscarf is a fine Kashmiri pashmina. The deep green of dreams. The sacred colour. It needs a wash but I don’t object to the faint warm odour of it. A peasant woman would never wash her scarf. I’ve become accustomed to strong animal smells here alone with Sherry.

Suicide is for strong people. Suicide is not for the likes of Barnaby. Barnaby has spoiled suicide for me. It is so annoying. I tremble and have no strength. The tea tray jiggles in my hands as if it will leap out of my grasp and run away laughing into the garden, like one of my tormenting brothers risen from his grave to mock me again. Each of the seven lidless teapots on the shelf above the Rayburn represents a period and a particular friendship. I realised this the other day when I broke the lid of this one. Don’t worry, I shan’t bore you with a catalogue of all that. My two brothers shouting Gabby into my face until I wept with fury and pursued them helplessly around the garden at Elsinore. Elsinore! You see how I was schooled in grandiosity. They became grey-suited chairmen of their own great companies. Members of the Melbourne and Metropolitan Board of Works. Terrified of publicity. Terrified of taxation. Both dead. Their wives dead. Elsinore given to the state. The garden cut up to make room for the developer’s blocks of yellow-brick flats. That vast cold house a rehabilitation centre for the hopeless of this new age that is not my age. Elsinore, my childhood home that was never homely. It should have been bulldozed instead of classified. I turned my back on it and on them when I met Arthur. When my father met Arthur he said to me, ‘There’s only one thing wrong with your Arthur, my dear.’ I asked him what that might be. ‘Arthur doesn’t think enough of money,’ my father said. I answered, ‘And your trouble, Father, is that you think of nothing else.’ He did not forgive me. We were not friends. Were we ever? I loathed them all. I was afraid of them. I still am. They damaged me. My fear of them made me hysterical. I felt trapped with them and the only thing I could do was to scream and break things and refuse to eat. Even though they are dead the trap they set for me then is still in me now. I still scream and break things and refuse to eat. Not as often, but I do it. I dread what their cold world of money worship might yet do to me in the vivid nightmares that have begun to haunt my feeble years. You would not believe the awful conviction in the nightmares of the aged. They are a fearful assault. There is no resisting them.

Darling Uncle Mathew, he is still the saviour of my childhood. There was a touch of the poet in him and they despised him for it. He was the only one of them to die poor. They refused to help him. I have wondered if Mathew might have been the result of my grandmother taking a lover. Not the milkman, but some man cultivated, wayward and of a generous spirit. If she did have an affair, her manner gave no hint of it, unless in the very firmness of her implicit denial. Sequestered, she was. As tight as a dried fish in her corsets. The dowager Queen Adelaide. Her lips withdrawn into her mask. Severe in her reproach of all things joyful. The mistress of Elsinore to her last day. The laughter of children gave her migraines and she would not tolerate it in her house. My father’s mother. Grandma Ballard. Mother to the founder of our fortunes. And there were several fortunes. For a time the brothers Ballard (excepting Mathew) accounted for the largest fortune in Melbourne. I shall say no more. That lot will not be resurrected by me here. I will not be lured into an account of their hideousness. Truth does not require it of me.

I was eleven when Uncle Mathew kissed me within the canopy of the peppercorn tree in the garden at Elsinore. So gently did he put his lips to mine that a butterfly might have landed on me, the touch so exquisite my body bloomed for him with a pang I have not forgotten. That pale afternoon the beauty of consolation entered my life. For Mathew consoled me, as he consoled himself, not only with his kisses but with the secret that we are each born with a gift. I pressed my ear to his chest and listened to the strong rhythm of his heart. His voice was soft and unhurried, and when he spoke wide acres of time waited to be filled with imagination’s charmed possibilities. His was a landscape beyond reality.

‘Not everyone uses their gift,’ he told me that day, his hand on my side, his fingers warm through my dress. ‘Some,’ he said, ‘do not even realise they have received a gift. For them the gift remains mute, dormant until the end.’ I knew he spoke of his mother and his brothers. I said, ‘You mean until they die?’ I wished to hear him say it. His fingers pressed my ribs and he held me close in his embrace. ‘Yes, my darling, until they die.’ A hardness in his voice at this. And I wished then for the deaths of all of them. The smell of Mathew’s skin through his linen shirt was of herbs and blossoms and strange distant places. ‘Others,’ he said, ‘do not wish to acknowledge the gift. They see the burden of it and are frightened by what it demands from them, that it will challenge them to perform above themselves or else see them fail. They disown their gift in favour of the coarse reality of money. They loathe the creative life of others and strive to stifle it at any cost. They are best at cruelty.’ His mother’s fierceness stood over us and he lowered his voice and whispered, ‘In their most secret thoughts they believe in an untried quality within themselves that would prove equal in merit to the merits of the most gifted—if only they were to tryit. That is their secret despair, not to have tried their worth.’

That is the way Mathew talked; lover, poet and philosopher. He was too kind and gentle for this world and failed to leave an impression on it. He spoke to me as if admitting me to secrets gathered from places I would never visit. I loved him and felt safe with him. And wasn’t he comforted by my innocence and my belief in him? None of the others spoke to me in his way. If they spoke to me at all, it was to correct me or to offer me advice or to mock me. They did not know how to speak of love or poetry. The imagination was a locked door for them and they feared it. I locked my lips and my ears to them too. It was the country of Mathew I was determined to inhabit when I grew up.

When I was seventeen and home from school for the Christmas holidays I saw Uncle Mathew for the last time. And perhaps he knew it was to be our last time. For we sat in the garden again on the seat in the shelter of the peppercorn and when I asked him, ‘What is my gift?’ he kept his silence for a long time, looking at me tenderly, before he said with an undeclared sorrow that puzzled me, ‘My darling Autumn, yours is the gift of recognition.’ It was his melancholy he would have me understand, not that the world is hard and sad but that life is beautiful and must end. I asked him how he could be sure this was my gift. ‘You are the only one among them,’ he said, and there were tears in his eyes as he said it, ‘who has not scorned me or accused me of failure, but has celebrated my struggle to make something of my poetry.’ I took his hands in mine. ‘But I love you, Uncle Mathew. Whatever you had done I would have loved you for it.’

A year later he found his death, alone and destitute, in the backyard of a pub in a dismal village in County Kilkenny, Ireland, where he had foolishly strayed in search of the roots of his poetic gift. I wish I had been there to comfort him. I denied him my lips that last time in the garden at Elsinore. I was too awkward with myself at seventeen to permit it. And afterwards I regretted denying him. I still do. I could have let him have everything and it might have given him hope.

But he was right. I was gifted to recognise the strengths of others, often before they saw their strengths themselves. I was the one who gathered them together and brought them into their own light and into the confidence of the admiration of their peers, without which many of them would have faltered and fallen by the wayside, like poor solitary Uncle Mathew himself. He had taught me that the country of the gifted is a dangerous place to be alone in. I vowed that I would always keep myself at the centre of a group of writers, artists and thinkers.

And that is what I did, with Arthur at my side. Until it was all torn apart by envy, betrayal and despair.

When I saw Edith on the street it shocked me. It was her walk that was familiar. That same balanced containment which, when I first met her, made me think her prissy and lacking in seriousness. That soft young woman’s walk in an old woman. A demon voice whispering in my ear, Edith Black! See? There! That’s her in the green hat walking away from you. The only woman on the street wearing a hat. I felt as if I’d been shot. She stopped and turned around and looked straight at me. My hand went to my face. When she started back towards me I thought she had recognised me. I was unable to move. But she walked past me and went into the chemist’s, where I’d just been to get my prescription filled for the life-saving drugs I take every day by the handful. As I watched Edith go into the chemist’s I realised she could have been my oldest friend in the world today instead of my oldest enemy. Instead of taking her man from her I might have put my arm around her and given her a kiss. She was without guile. My throat thickened and I wept. Why did I weep? I don’t know. I wept, that is all I know. And something changed for me. I have always been indifferent to the why of things. It is what happens to us that matters, not why it happens to us.

I kept diaries all my life. Notebooks. What the Germans call Tagebücher. Notes on my days. The incidents that filled them, or the voids that made them echo with my cries of anguish. That smell of burning in the summer air today is them. This blue smoke in the sunbeams here within the coach house. I must go and stir the ashes. Books burn badly. My despair. My hopes. My girlhood dreams. All that stuff. It goes stale quicker than cabbages. When I got home after seeing Edith I went out to the back veranda and poured a large whisky and drank it off in one go. Half a bottle of whisky later I was in the study collecting my notebooks from the shelves above my desk. They went back to the days before Mathew kissed me under the peppercorn. The earliest of them had pressed violets between its pages from the garden at Elsinore. I must have been seven. What started me keeping a diary when I was seven? There was another with the impression of my girlish lips from my first lipstick (stolen from my mother’s clutchbag). Later notebooks with boys’ love letters pasted into them. I gathered them all from the shelves and stuffed them into an empty wine carton. This afternoon I dragged the carton along the passage and out the side door to the forty-four-gallon drum that Stony incinerates our rose clippings in. I reached into the drum with the iron poker from the library and stirred them around, pieces flying up and making me squint. I watched the pages curl and catch, my antique past in the flickering sparks crawling along the edges of the old paper. So what? It was time to burn them. An added delight in watching them burn (knowing there is no return from fire) was that Biographers love nothing more than notebooks.

Arthur’s 1934 Pontiac. I’m standing here looking at it. We drove down to Ocean Grove in it to see Pat and Edith. It’s parked over there where he left it, God knows how many years ago. The key is still in the ignition. I suppose the battery is dead. My poor Arthur. A scavenger has stolen the Indian head from the bonnet. My beloved Arthur and I that summer afternoon in 1935, three years before we met Pat and Edith. Here, in this old coach house, is where it began for all of us. It stood as crookedly then as it stands now. Arrested in its fall. When Arthur and I saw this place we didn’t need to say anything. It matched our dream. Old Farm. It had been for sale for years. A piece of land beyond the suburbs. An old weatherboard house and this dilapidated shed with the open side. A sixteen-acre paddock and the river winding along the bottom boundary. Fragrant eucalypt forest on the far side of the river. Everything we had dreamed of. All wonderfully neglected and in need of the love we had to give. It is a big shed with a mezzanine, its boards sprung from its frame and grey with age. Now there is the roar of the freeway and the suburbs hem me in. It used to be that if you stayed in one place long enough you eventually became a local. Now if you stay in one place long enough you become a stranger.

I’m a remnant from another time. I don’t eat properly. I can’t be bothered cooking. My breath is foul and I fart continuously. I’m accustomed to the smell. My stomach is a fermenting tip. I eat cabbages every day. I’m like a poor Chinese. There is a box of them—cabbages, not poor Chinese—behind the kitchen door. The house stinks of my farts and boiled cabbages. I don’t care. I do care! No, I do care, but I can’t summon the will to do anything about it. I was such a skilled housekeeper. Stony brings me cabbages. He’s the last of the market gardeners. He has hands like a stone breaker. When we came here it was cherry orchards and fields of strawberries around us. Now there’s just Stony’s cabbage patch and the suburban houses. All far grander than my dear old Old Farm. I might yet burn it to the ground. When this is done. There is no return from fire. We are not Shadrach, Meshach or Abednego. Are we? With no smell of fire on us. I can’t remember now why those three young men were put to the flames in the first place. To prove something, I suppose. Their heroic faith, was it? Or something purer? Another distraction from reality. The smell of fire is on me today. This dress will hold it. It is a smell that will see me out. The smell of fire and boiled cabbages. There are worse fates than destruction by fire. The ancients knew that. We have forgotten everything strong. It can’t have been today that I put my notebooks in the drum, can it? They must be still smouldering from last night. Oh, I don’t know and it doesn’t matter. Chronology’s not everything, is it?

Arthur and I came here that summer day in 1935 arm in arm, in each other’s arms. We knew at once we had found our haven from our terrible families. We were pure then. Yes, we were. Pure in our spirits and our intentions. And he was innocent. His family almost as wealthy and quite as mean and twisted as my own. He had given in to the love knots of his mother and become a city lawyer. But enough of that. There, just there by the back wall beside the Pontiac, is where we made love that first joyful afternoon. Where the hot eye of the sun is burning this very moment. Hay was piled loosely then. Loose hay for us. We were golden and young and in love (though not violently. Arthur was my refuge). I had to instruct him. I may as well tell you now, this story does not have a happy ending. I have never had a child. Not of my own. It wasn’t possible. There was a simple, unpleasant, gynaecological reason. If that is how you spell it. And speaking of spelling, have you noticed that prenatal needs only the displacement of one letter to become parental? It doesn’t take much. Ever. For one thing to become another. Usually its opposite. Love become hate. Heaven become hell. Good become evil. Laughter become slaughter. One letter. That is all it takes. You know the rest. Word and wound.

He—Pat I mean, not my dear gentle Arthur—was my greatest work of acknowledgment. He was the one on whom I spent my gift without holding anything back. I knew him the moment I saw him—well, not quite the moment, but within the hour. He squinted in the fierce light of his ambition. He was not like Picasso. He did not have those famous hungry eyes. Pat had a deep eye. That is what I saw. No one else saw it. Pat Donlon, with his white-blue eye that he tried to conceal from us by squinting. Concealing from us the terrifying nakedness of his ambition. Even he was unsure of it. Until I opened him to it, he was unsure. So there! He was married to Edith when Arthur and I first met him. She was a beautiful girl, lovely and sad. A little afraid of him and what she had done. Afraid of his intensity. Afraid of what she had done in tying herself to this man’s course. But she loved him. And she had courage. We both saw that. Oh yes, how she loved him. If God, who made us all (I suppose) and gave us our passions were to give me my life to live over I would be kind to Edith. I would put my arms around her and take care of her and make her feel safe and loved. What did I do? I took her man from her. I took Pat. It was easy. He was offered to me by fate, so I took him. I never considered Edith. My gift of recognition was called on by Pat in a way it would never be called on by anyone ever again. It was my fate to take him from her. So I took him. Arthur trembled with it, but withstood it. My poor dear lovely Arthur. Like heartless Nebuchadnezzar with his three young men, I put Arthur to the fiery test. He survived but he didn’t come out unscathed. Burned to the bone, he was. White as ash. A great innocent gentle part of him destroyed. Not to be recovered. My Arthur. What I made him endure. How I still love him.

Edith was forgotten by us. So I will give her portrait the first place in this testament. Pat will have to come second to her for once. The portrait of a young woman, at the time of life when we need our portrait painted: when we are young and beautiful. Not when we smell of cabbages and smoke and our own farts. I shall do Edith the honour of remembering her youth. You may not like him (Pat) and I can’t expect you to like me. But you cannot dislike Edith. She was the first to be sacrificed to the violence and the hunger of his ambition. An ambition of such rapture its severity frightened even him. As if it were an affliction that came at him when the weather changed or the moon was full. She and their child, Edith and the little baby. The first to be fed to the strange dark blessing, the furnace of his art. If that is what it was. Or am I getting too melodramatic again? That speechless art of his that hangs today in its silence on our gallery walls. His art become a kind of silence itself. A shroud. Something awful about it that I still cannot confront. Why did we do it? Who has it served? Edith is forgotten. She was like a child when Arthur and I first met her, still obedient to the hopes and sacred values of her parents and her lovely grandfather. A girl incapable of revolt or betrayal against those who had nurtured and tutored her. She was shocked by such things. Embarrassed by them. Confused by them. I can see the blush rise to her lovely cheeks now when I spoke in her presence of my hatred for my family. That was something she could not understand. My revolt against them shocked her sense of what was right.

I was his acolyte. What is that? Acolyte? These days one needs to explain such words. An altar attendant of minor rank, my dictionary says. Not just his accomplice, but something sacred in the ministry of it. That was me. I drew him out and encouraged him and shared the mad illusions that made an artist of him. And I paid a terrible price for it. He was creative in the conventional understanding of that notion. An artist. But you will have to ask, as I have had to ask, whether what we destroyed in the service of his creations was of greater value than what he and I produced. Was he, was I, just as cold, just as ruthless in the struggle to deliver his art, as my father and uncles (saving Mathew) were in their struggle to amass a great fortune? At any price. Always at any price to others. Never to themselves. They sacrificed nothing. It was always others who were made to pay. Was there not as great a coldness in the way Pat and I exercised our ambition as the coldness I so despised and feared in my family? The coldness I fled from? My heart aches with this question: was I not my father’s daughter after all? Inescapably branded from the cradle with his will? There may be no answer to questions such as these. Or the answers may be obvious. Something to do with the simplest moral principles of our humanity. We will all have a different answer, I dare say, those of us who love art and find in it our consolation, and those of us who live contentedly without it. But in asking the question we would do well not to forget Edith Black and her child. To forget them, as they have been forgotten, written out of our record, written out of Pat’s history, is to lie to ourselves about the nature of our culture. To forget Edith and her child is to lie to ourselves about the nature of our art and what it is we worship in it.

Here she is then, Edith Black. The best I can do for you. A realist portrait. Realism, that most difficult of styles, filled as it is with intricacy and contradiction.

2Edith Black, 1938

IT WAS A FINE DAY. THE SUN WAS SHINING JUST FOR HER. THE SEA running a heavy swell after the previous night’s storm. The sound of the sea in the room with her now. He had raced down the track to the main road on his bicycle earlier without telling her where he was going or when he would be back. She stood at this window then, where she is standing now, watching him go.

It is already midday. The postman has been and there is a letter sticking out of the box by the gate, a white triangle catching the sun, as if a white bird has alighted there. The letter will be from her mother. She will walk down and fetch it later. She has come out of the studio and rattled the stove into life and made a cup of tea, a drop of bluish milk from the neighbour’s blue roan cow, and a half teaspoon of their precious sugar stirred into it. She stands at the window sipping her tea and looking out at the green hill, the cup held by its slim handle in her right hand, the saucer in her left. The cup and its saucer are delicate pieces of English bone china decorated with a crowded pattern of lilac blooms. One set of a pair on temporary loan from her mother. ‘Lilac Time’. Like everything in this house, and the house itself, temporary and borrowed. And not her mother’s best, but her second best, or perhaps even her third best. Expensive nevertheless. A measure of her mother’s trust. ‘Until you two can get a few nice things of your own together.’

She is pleased to see that the horse is still there. The green hill, where the horse stands, sweeps upward from the foot of the garden to form the soft curve of her near horizon, like the warm belly of the earth. She half closes her eyes, permitting this thought a little space. High above the paddock immature white clouds silently approach from the troubled sea across the cold blue of the sky, which, she notices suddenly, is exactly the white-blue of his eyes. Yes, white-blue. Like the eyes of his hero, the poet Rimbaud, whose verse he never tires of reciting. She hears it now, her own voice translating for him, I hadcaught a glimpse of conversion to good and to happiness. She gives a small, nervous laugh at the thought of him, at the thought of where he might have gone this morning. Some sense with him always of the terrible disasters that await us in life, his urgency, his mad desire to be bodily engaged with the future.

The upward sweep of the green paddock is decorated with yellow oxalis flowers. It is a counterpane sewn with morning stars. Her mother’s handwork, for example. Finely embroidered silk thread. The Latin names of the flowers done in sylvan green around the border, so fine a magnifying glass is needed to see the individual stitches, and even then . . . There is nothing cruel or cynical in her mother’s life. All painful memories have been put down, like old family dogs. Quiet, calm, sensible. That is how it is at home, in Brighton and on the farm. Wherever her mother presides, there everything is as it should be. No daisies in the lawn. The past unpicked and restitched. The work goes on. Their saving routine. Church on Sundays, with Dr Aiken presiding at Flood Street, his thin nose and sad intelligent eyes. A good man in the claim of his grateful parishioners. His apologetic frown a perpetual reminder that there is some terrible problem to be resolved before we can all move confidently to a full enjoyment of our lives. Saint Paul advised the Philippians to Rejoice in the Lord always: and again I say, Rejoice. But Dr Aiken hasn’t rejoiced. He has puzzled in the Lord. What he has missed is something vital, the key to happiness eluding him. His life has been without a companion. He has not seemed to wish for a woman by him. The manse a cold redbrick darkened by moaning cypresses, the shelves of his study closely inhabited by puzzling tracts to do with something he does yearn for, the Ultimate Truth and the Christian God—staples of his divine preoccupations. No touches of the floral, either in teacups or counterpanes, to lighten his days. And such a handsome man, his manner gracious, his hands fine and well shaped, noticeable when he bows his violin, and other features of nature’s approval gracing his gentle person. A match. But all for nothing, so it seems. His solitariness a puzzle to her mother. For the Presbyterian assembly does not bar its ministers from the sacrament of marriage. Even so . . .

No, the floral counterpane is surely more exotic than that, Edith decides firmly and sets her cup in its saucer in the dulled stone of the sink, the sink’s crazed glaze the perfect hue of old bones, the fine lines possibly an antique script. Clink, the cup says sharply to its saucer and Edith looks down and steadies it, breathing a murmured apology. Once again she has been dragged back into memory and her old home and her mother. Her mother. The decorated hill is not a floral counterpane at all but is something Persian and is not of her mother’s world. A Persian embroidery. The work of silent hours and days when a woman in her solitude dreams of distant events that never were but might have been, and bends her head to her needle in the soft lamplight and smiles at the tiny golden flowers. Pretending that her dreams are memories.

Standing at the window, her fingers still touching her mother’s lilac-patterned teacup, the smell of the wood stove in the air, something of hot iron and smokiness, Edith thinks: How peaceful it is here. How lovely. How at home I might so easily know myself to be in this little house with him, if only . . . The horse is a mare. It is an old brood mare, the points of its hips prominent, gut-hung, its spine bowed with the bearing of many foals, its brown coat dry and wintry. Equus caballus. Edith has known the companionship of horses since her childhood on her father’s farm. The old brown mare stands side on to the hill, her hollow flank towards Edith. She, the mare, looks as if she is expecting someone to come over the horizon; her ears pointed forward, the imagination of oats in her distended nostrils. Edith wonders where she has come from and what has prompted their frugal neighbour to offer her the generous pasturage of his paddock. The horse was there this morning, large and brown, turning its great head towards the house when Edith came out the back door to feed the hens and collect the eggs, a newcomer like themselves, curious, alert and a little apprehensive. After feeding the hens—there were no eggs—Edith fetched a thick slice of bread from the house. Gently coaxed, the mare approached the fence and lipped the offering from her hand. The calm innocence of the mare’s eye. It is a fact well known among horse people that the horse has the largest eyes of any land mammal. ‘Will you be lonely in Mr Gerner’s paddock with only the milker for company?’ At the touch of her voice the mare lowered her long lashes and bent her head. The horse is highly sensitive around the areas of its nose, its eyes and its ears. Edith stroked its silky nose. ‘Stallions once trembled before your beauty.’

The Southern Ocean lies beyond the horizon that is formed by the swelling rise of Mr Gerner’s green paddock. The Great Southern Ocean, her grandfather, the painter Thomas Anderson, called it. Encircling the world. Its boundaries indeterminate. Taking her hand in his large knobbly one and leading her forefinger on a journey across the old atlas, Alexander KeithJohnston, F.R.G.S., 1857, on Mercator’s Projection. A great book all the way from the family home on the bank of the Nith between the lofty hills and fertile holms of Dumfries, the largest private house in the county. The book. Yes. Shelved there once upon a time in his own grandfather’s library, another Thomas Anderson in a line of them from the Border country, the book’s elephant folio sheets giving off a smell of the other world on the other side when he laid it open on his broad oak desk, as she stood close beside him in his studio in the house where her own mother had been born, a dwelling elegant and Victorian, on the fashionable foreshore of Brighton.

To speak of the other side is to refer to death by another name. Even then she knew it. Her grandfather’s jacket smelling of Erinmore tobacco. The grip of his hand making the first joint of her finger bend like a hockey stick on the heavy paper as they made their imaginary journey together, crossing the ocean (whose breathing and sighing is with her in the kitchen at this moment), so firmly guided by him then; ‘We sail past the stormy tip of South America, then touch South Africa. A big tack between Crozet and Kerguelen islands. And here we are already!’ Leaning together, his moustache tickling her cheek now, ‘The bottom of Australia. I—think—I—can—just—see—us. Can you see us? Yes! There we are! See, the pair of us?’ His free arm around her, cuddling, just the two of them in the quiet of their own story, among the smell of old books and turpentine. She misses him. It is already four years since his housekeeper, Mrs Dress, found him lying on his back beside the long kitchen table, his feet together, a familiar old man clad in pyjamas and slippers, his glasses and his pipe and tobacco pouch neatly arranged beside him, his striped cottons freshly laundered. But, oddly, without his plaid dressing-gown. Perhaps he thought the ancient garment unfit for the occasion? ‘So there you are,’ Mrs Dress said, stepping around him, and made herself a cup of tea before telephoning his daughter. He had evidently felt the approach of the moment. A wavering light at the periphery of his vision, was it? A mild anxiety and tightening across his chest? We shall never know. And had prepared himself so as to cause the least shock and trouble to those whom he cared for and whom he was about to leave on this side.

Edith wonders if she will always miss him. He had no time to say goodbye but was gone, suddenly, without a word. She had found her mother by the telephone, sitting on the big camphor wood chest in the hall, weeping. Will she always carry her loss as she goes on through her life, Edith wonders, becoming old herself one day, a grandmother, her grandfather a noble resident of her childhood memory, loved and missed? Will it always be like that? Or do our dead eventually leave us? He is her inspiration for this life that she has chosen, and she needs his approval for her work. Art. Her mother’s father. But Edith does not call herself an artist. She is far too uncertain of herself for that; too deeply conditioned to the habit of womanly modesty to openly admit the secret ambition of her heart. He, her grandfather on her mother’s side—whenever sides were taken—had been either happily ignorant of or indifferent to the innovative schools and styles of his time. The great artistic debates and feuds had left him untouched. His palette throughout his life a range of golden browns with their own inner light, achieved with a knowledge of the classic craft. He had seen no reason to snub the tradition that had given him his splendid livelihood. He was not a visionary. He did not see it as his business to challenge the authority of his masters. His subjects were leisurely pastoral scenes, farm buildings, crops and roads leading somewhere or other, a girl sometimes with a straw hat and ribbon going somewhere or other, a workman in a field with a horse, the sound of birdsong and maybe a butterfly or two. His was the reassurance of a kindly nature for the drawing rooms of the well-to-do city folk and great country families who were his patrons. He might have been making sturdy chairs for the ease of their minds and their backs. A reliable craftsman, they were pleased to revere him and to acclaim his genius in the works he made for them. Occasional portraits, too, of children or their fathers (when honours were bestowed), commissioned by the wives, were competently produced when required. He was a Melbourne man. Solid, reliable, of good Scottish stock. Sydney did not know him. Although almost never hung these days, a work or two of his can still be found in the inventory of the Scottish National Gallery in Edinburgh.

He wore a dove-grey fedora with a wide black silk band and a grey three-piece suit with a plain bow tie. His moustache was large and brown and prickly. He looked like a painting of himself. A tonal head and shoulders of him, the brim of his fedora shading his eyes, hung in the parlour of the Brighton house, done by the controversial Max Manner—who did call himself an artist—and tendered in lieu of rent when Mr Manner brought his family home from France, stony broke and with nowhere to live, bolstered nevertheless by the assurance of his own genius. All that before the steady years of Manner’s prosperity and influence. Comfort and opulence in the grand house in Kew, where his two daughters, lissom Elise and chubby Simone, lived on in genteel poverty long after the great man himself had gone over to the other side. As the years went on without him the house grew seedy, green around the brows from leaking guttering and failed damp courses, the garden splendidly overgrown, the two devoted spinsters insisting on the grandeur of their father’s achievement to their last days together on this wonderful earth. Simone, the younger of them, played the role of maid to the elder’s haughty chatelaine; Elise receiving her visitors seated in the parlour, veiled in layers of pink and apricot chiffon, her lips bright red (a little askew), her purpled eyes challenging her visitor to exercise the fine manners and graces of an earlier time. Their father’s early poverty was never referred to.