6,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

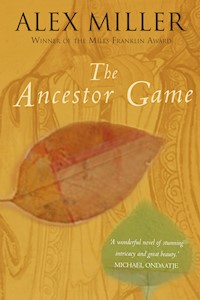

- Herausgeber: Allen & Unwin

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

Steven Muir, August Spiess and his daughter Gertrude, and Lang Tzu all acknowledge a restless sense of cultural displacement, an ambivalence in their relations with the culture of European Australia. Steven left England for Australia as a young man and his one attempt at returning is unsuccessful. August Spiess, although he speaks frequently of returning to his native Hamburg, fails to make the journey, as does his daughter Gertrude. Lang Tzu's very name defines his fate: two characters which in Mandarin signify the son who goes away. The 'game', however, does have winners. For despite their yearnings for the home of their ancestral dreams, a desire to belong somewhere that is truly their own, none of Miller's characters leaves Australia, and each in their own way comes to see that to be at home in exile may be a defining paradox of the European Australian condition: the paradox of belonging and estrangement that perhaps lies uneasily at the heart of all European cultures.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2017

Ähnliche

This edition published in 2003 First published by Penguin Books Australia in 1992

Copyright © Alex Miller 1992

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. The Australian Copyright Act 1968 (the Act) allows a maximum of one chapter or 10% of this book, whichever is the greater, to be photocopied by any educational institution for its educational purposes provided that the educational institution (or body that administers it) has given a remuneration notice to Copyright Agency Limited (CAL) under the Act.

Allen & Unwin 83 Alexander Street Crows Nest NSW 2065 Australia Phone: (61 2) 8425 0100 Fax: (61 2) 9906 2218 Email: [email protected] Web: www.allenandunwin.com/uk

National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry:

Miller, Alex. The ancestor game.

ISBN 978 1 74114 226 6

E-book ISBN 978 1 92557 614 6

For Ruth and Max Blatt

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I would like to express my thanks to Professor Bao Chien-hsing, of the Shanghai Foreign Languages Institute and to the painter, Yehching, for their generous assistance while I was in Shanghai and Hanghzou. I would also like to express my thanks to Nick Jose, then Australia’s Cultural Attache in Beijing, for introducing me to Ouyang Yu, who was at that time teaching in Australian Studies at the East China Normal University in Shanghai. Ouyang has since become a firm friend. My chief debt, however, is to Barrett Reid, Stephanie Miller and Bryony Cosgrove, from whose concern and candor this book has benefited.

CONTENTS

1 Death of the Father

2 Only Children

3 The Lotus and the Phoenix

4 The Winter Visitor

5 No Ordinary Child

6 Portraits

7 The Mother

Homecoming

Men

The Campaign

Signs

8 An Interlude in the Garden

9 A Memoir of Displacement

10 The Entrance to the Other-World

11 Reflections From the Gazebo

Thirty-Four Days

War

Present Reality

The Gift of Death

Victoria

Into Regions of Uncertainty

12 The Lovers

13 The Little Red Doorway

DEATH OF THE FATHER

In a wintry field in Dorset less than a year ago, I enquired of my mother, You don’t want me to stay in England with you then? She, clipping her words as if she were trying out a new set of shears on the privet, replied, No thank you dear. I waited a minute or two before venturing the merely dutiful alternative, You could come out to Australia and live with me? Thank you dear, but 1 think not.

We resumed watching a pair of swans. Their pale forms merged with the river and the flat fields and the sky, then emerged again mysteriously, as if propelled by the unseen hands of giant children at play. Nothing else moved. Everything around us was grey, luminously grey, and very cold. We were closed in by fog. There was only the rushing sound from the motorway a mile off. As I stood beside my mother I realised I’d arrived at a moment of decision. Ill-defined anxieties flickered in my mind. I remembered the Chinese refer to these moments as dangerous opportunities.

We watched the swans glissade into and out of our view, on the river that was indistinguishable from the sky, and we waited until the bruised sun had dissolved. Our cold vigil in the field at sunset was our homage to the memory of her husband and my father. There was to be no lasting memorial. There had been no service. There was no patch of ground to remain sacred to his memory. He probably would have liked there to have been: a headstone set among others’ headstones and incised with a couplet from Burns: Nae man can tether time or tide; The hour approaches Tarn maun ride.

But my mother didn’t care for headstones, or for her husband’s taste in poetry, and so, as she was now in charge, there were neither. There’d been no arguments about these arrangements as my father had had no friends to argue for him, and my mother and I were the only surviving members of the family. She took my arm and walked me back to her home across the frosty fields. To have seen us we must have looked like any English mother and son taking their habitual evening constitutional; persisting, despite the bleak weather, the way the English do persist with such things. In fact neither my mother nor I was really English, and we’d not seen each other more than two or three times in twenty years.

I hadn’t returned to England to bury my father, but to be present for the release of my first novel. It had provided me with an excuse for the journey. I’d hoped my book, which was set in England, might prove the basis for a reconciliation with the country of my birth. I’d hoped something might have healed between us by now. And I’d been on the alert for a sign of this healing when I telephoned from the airport to let my parents know of my arrival. My mother sounded put out when she realised it was me phoning. Oh it’s you Steven! I thought it must have been the doctor ringing back. Your father has just died.

My gaze roved appreciatively over her lovely English furniture and the porcelain in its cabinets, pieces she’d collected with care over the years, and I saw how deeply she now belonged to this place, how buttressed against dislodgement she had grown in my absence, a successful cultural graft drawing her sustenance with assurance from the rootstock of her adopted country.

Although it was winter she’d managed a dark arrangement of velvety chrysanthemums. I couldn’t resist the impression that these flowers signified a celebration rather than an occasion for mourning. She looked at them when we came into the room in a way that did not ask me to share them. We sat in armchairs on either side of the gas fire, she in her own and I, I supposed, in my father’s, and we watched television. It was the London Philharmonic with Solti conducting. My mother moaned and swayed as if she were the cello embraced by the thighs of the cellist. Then, when Britten’s symphony ended, she rose from her chair at once, switched off the television and said matter-of-factly, That was lovely. To detain her a while longer I responded to an offer she’d made me earlier, I’ll take the book on Nolan then. If you really don’t want it?

She paused behind my chair, holding the tray with our cups and the supper things on it, and looked down at the top of my head – I could see her reflected in the screen – and she reminded me, You sent it to him for his sixtieth birthday.

I’d forgotten. In the instant of speaking I’d thought I was selecting the book randomly from my father’s things. Something of his to remember him by, not something of my own to recall myself by.

He never looked at it, she said and laughed uncomfortably, impatient. He detested that sort of painting. Anything which reminded him that artists have abandoned the pictorial manners of John Cotman and Francis Danby made him angry. I thought you’d sent it to provoke him. He thought so too, you know.

There was a pause, then she said, I don’t pretend to understand you Steven.

She cast off this remark on her way out to the kitchen as if she were casting me off. I heard her clattering the things in the sink. She began singing the cello from Britten’s symphony. I realised that she couldn’t wait to have done with me so that she might at last get on with living her life quite alone. Her verdict, it seemed, was that if I’d wished to belong in England then I ought to have stayed.

When she came back into the room she did not sit down again but plumped the cushions on her chair and stood and waited for me. She was ready for bed. I wanted to say something to her about how I felt, but I was unable to.

I hope your book does well, she offered at last, as if she were referring to a world composed of a thin unreality that she could not quite bring herself to believe in.

Thanks.

Still she did not move. There was a mute tightening of the congested intensity between us. Then, You never wrote to us Steven! It was years before we heard anything from you. We thought you must have perished in the outback, or whatever it is they have there. Then that book arrived from you, like a taunt. You can’t blame us now for this whatever-it-is that’s troubling you.

I took the heavy Sidney Nolan monograph to bed with me and sat up with it open across my knees. There was an inscription on the front end paper. I recognised the hand as one I’d tried out for a while, upright and orotund, before lapsing into the backward slant that came more naturally to me – a calligraphy, this, in which my words appear to test the way forward with one tentative, extended toe. Dearest Dad, With all my love and best wishes for a happy birthday, your son Steven. It was dated August 1961, the year of the publication of the book. How very up-to-date I must have thought myself then. I remembered writing the inscription. I remembered the fountain pen I’d used. Now, towards the end of my thirty-ninth year, I was the first person to read my birthday message to my father. Had it been my intention to taunt him, the antiquary and amateur watercolourist, with this paean to brutal modernism from the far side of the world? How else might he have viewed this unexpected gift from his only son after so many years of silence? It must have seemed to him – this man whose ‘eye’ had remained adjusted for more than half a century to the nostalgic fragilities of the faded watercolour sketch – to be a coarse rejection of the traditional craft he believed himself heir to and therefore guardian of. He must have shuddered with outrage as he placed the quarto volume on his bookshelf, unopened.

Uneasy with an expectation of what I was to reveal, I turned the page and began to read the essay before the plates by Colin MacInness. Australia is an Asiatic island that Europeans inhabited by accident, it began. And a little further down the page, Everything about Australia is bizarre. I read until I lost interest in the writer’s insistence on a uniquely eccentric nature for Australia and for the ‘kingly race’ of Europeans who inhabited the continent. Yet I wanted to be reassured. I wanted to believe in the book. I turned to the plates.

There were pictures of Ned Kelly in the bush, and pictures of abandoned ploughs in flat, empty country that couldn’t possibly grow anything, and there were carcasses of horses and cows and vast red uninhabited landscapes, and there were ghostly portraits of Light Horsemen with emu feathers in their slouch hats, invoking the Anzacs and Gallipoli. And then, in the midst of these images of soldiery and abandonment and of sterility and failure, there was Leda and the swan, the divine parents of the mythical Clytemnestra and Castor and Pollux, and of Helen of Troy. The landscape was still unmistakably Australian. The swan was white.

What was one of the Queen’s swans doing here in this sinisterly brutal world, which appeared to rise less upon a vision of human tragedy than upon a bleakly dispassionate view of a civilisation that had failed: a European civilisation that had failed to take root in an environment hostile to its ageless central icons of the plough and the warrior. I examined the rest of the pictures. The images referred to an Australia of which I had no direct experience. The white swan, I decided, must serve as the cipher by which the other images were to be read. Its persisting whiteness I took to be sufficient evidence that the nature of myth must go much deeper and be less conscious and amenable to manipulation than was implied by the project of the book. It wasn’t that the pictures themselves were inauthentic – they were undoubtedly the authentic expressions of one man’s disappoint ment. It was the claims being made for the pictures that were inauthentic; the chauvinistic insistence that something unique and non-European had been established in Australia, when what I clearly had before me was an example of a regional vision located deep within the embrasures of a European tradition.

I closed the book and dropped it on the floor beside the bed. A thick pain was pushing up against my diaphragm and there was a whooshing in my ears. I lay on my side with my head over the edge of the bed and breathed shallowly, my arm extended, bracing myself against the book. There had been the failure of my father’s heart the previous Saturday. The swift attack that had killed him while I was making my way through the customs at Heathrow. Had I inherited his condition? Was this the revenge his outrage had required? Would my mother be standing in the field watching the swans again in a day or two, on her own?

After a few minutes the pain eased and the rushing in my ears subsided. As my hearing readjusted to the sounds of the world outside my body I realised I could hear music coming from my mother’s room. It was the ‘Dance a Cachucha’ from The Gondoliers. I pictured her dancing around her bed in her nightdress, gay and diaphanous, her thin, reddish hair flowing and translucent in the lamplight, celebrating her liberation from the onerous uncertainties of her Scottish husband and her Australian son. I listened gloomily to the catchy foot-tapping tune and to her dum-de-de-da-de-da-da-da and I saw how completely she had always kept her magic to herself. Was I returning to Australia in the morning to continue my exile, or was I going home? The book had been no help to me at all. Nolan and his Leda paintings had found their home in England long ago.

ONLY CHILDREN

At afternoon recess the man and the woman were there again in the staffroom. As before, they were in conversation by the gas heater. The heater wasn’t lit as the weather was fiercely hot, but the man held his hand out to it behind him every now and then as if he were in need of its warmth. She was taller than he by several centimetres. She was wearing a grey dustcoat and dark pants and she stood still and kept her hands thrust into her pockets. She didn’t look directly at him, even when she spoke to him, but gazed steadily in the direction of an unoccupied table tennis table by the far wall. She moved only when she laughed. She was about thirty. Perhaps younger. He looked to be somewhere between his middle forties and early fifties. But boyish. Small and light-boned like an adolescent. He had a lopsided way of standing, one small, rounded shoulder higher than the other, one hand clutching his elbow when it was not reaching for the heater, while with the other he held a cigarette close to his lips. He repeatedly took long, hungry drags from the cigarette, never removing it more than a millimetre or two from his mouth, so that the exhaled smoke fanned out against the open palm of his hand and enveloped him. He might have wished to conceal himself within it.

Unlike her, he was constantly on the move. They were indecisive movements, re-balancing himself from one foot to the other and, at certain moments, appearing as if he were about to set off somewhere only to change his mind at the last second and swivel round instead, reaching for the heater again, his point of reference. He was Asian. I preferred at once to refer to him in my mind as oriental. There was a coy and half-concealed refinement about him which insisted on this. He and the woman formed a composition of their own, a mobile triangle with the black heater its fixed vertex, distinct and unrelated to the activities of the other staff.

I was clear about why I was attracted to the man. The woman was more closed and difficult to read. But he looked as though he would know how I felt. Like my father, I had no close friends. I’d always managed well enough without such relationships. Once I’d not noticed the absence of intimacies of this kind in my life. Things had begun to change for me, however. Since my earliest childhood recollections I’d believed that if I could only reach deeply enough inside myself, one day I’d come upon extensive and complex landscapes rich with meaning and mystery, waiting for me to explore them. I’d believed the purpose of my adult life would lie in the exploration of these places. My confidence in the existence of this internal homeland, however, had eroded over the years. It had been my confidence in its existence, my belief in my own uniqueness, which had at one time provided me with an immunity from being infected by the mannerisms and beliefs of my father. Without it there seemed nowhere for me to retreat from him. Without it I saw that it was possible I might eventually grow to be indistinguishable from him.

On Thursday at morning recess the man was alone by the gas heater. He didn’t look my way, but as I approached him I was aware of him beginning to wait for me. I indicated the table tennis table, Like a game?

He checked me keenly, as if I’d suggested some extraordinary piece of mischief. Yes! he exclaimed with a throaty rush of breath. Let’s have a game! He continued to smoke while we played and never shifted from the one spot at his end of the table. He flicked the ball back to me with a practised twist of his wrist that was effortless and automatic. I dived and lunged from one side of the table to the other, trying to keep the ball in play, but succeeded in scoring only when he paused during a point to light a fresh cigarette from the stub of his old one.

We should play that point again, I offered. He wouldn’t hear of it. That was a good shot, he said. I laid my bat on the table. It’s too hot for this. He agreed at once. I gained the unsettling impression that he would have agreed as readily to anything I might have proposed, would have been prepared to fake enthusiasm for it.

There was a disturbing and fixed misalignment to his features. It was as if the right side of his face had been given a permanent upward nudge, resulting in a faintly sardonic expression, an aspect of amused irony stamped on his countenance at the instant of understanding. I was put in mind of my mother’s warnings that the wind would change and leave me with an obscene frog mouth and bulging eyes for the rest of my days. The wind must have changed for this man. I thought of him as having been touched, as having been wounded, by the powers of the enchanted world she understood but had been unable to share.

He was of her height and of a similar slight build and he, too, had about him a fey elusiveness. Where’s your assistant today? I asked.

He looked uncomprehending for a second. Oh, you mean Gertrude. He chuckled. That’s what I’ll call her! My assistant. He was shy suddenly, as if he thought he might be in danger of taking the joke too far. Gertrude Spiess. She’s a senior lecturer in drawing at the Prahran College of Advanced Education. He delivered this explanation with a formality that was almost ceremonious. She is an artist. A real one. She comes to do some emergency teaching here because she likes to do it.

His upward-tilted right eye observed me coldly all the while he was speaking. I found myself caught between responding to the diffident yet encouraging tone of his voice and the malevolence implied by the set of his features. With a seriousness that made the question more than casual, he asked me at one point was it difficult to teach non-English speaking children to read and write English. He awaited my reply as if he expected to hear from me something lucid and definitive.

There was an eagerness, a kind of complete disclosure of his own ignorance, in the manner with which he put his questions to me, that made it appear he must be prepared to accept whatever I might say as God’s truth. His manner flattered me with an implied expectation that I would adopt the role of expert in the English language. And I might have adopted it, except for the way he seemed to wait quietly within himself for just such a sign of my acquiescence. He noted my wariness and smoked his cigarette. His name, he told me, was Lang Tzu.

With ten minutes of the morning classes still to run I went in search of his art room. A terrible north wind had descended from the desert. The school grounds were filled with a roaring. A harsh rain of red Mallee dust swept down from the roofs and whirled in drifts about the yard. Through the noise of the storm a child was screaming. A few metres in front of me a boy was thrashing around on the near-molten asphalt. I couldn’t decide whether he was at play or had been hurt. I started towards him and he sprang up at once, shouting over and over a word which I didn’t understand. Opposite were the Gothic doors Lang had told me to look for.

The air was so hot against my face I felt sure things must begin to ignite at any minute. Plastic bags, milk cartons and other rubbish were being whipped into a vicious tornado by the scorching wind. At the doors I hesitated, fascinated by the fury of the heat storm, my hand on the iron latch, and was immediately engulfed by the fierce updraught of hot plastic and grit. I went in and dragged the door closed against the suction of the wind.

It wasn’t a classroom I’d entered, it was a barn. An assembly hall. A great cool echoing place of sanctuary, in which a pale illumination was admitted through several high, pointed windows composed of dozens of diamond-shaped panes of glass. There was an old and somehow familiar smell, composed of mineral turps, oil paint and book dust. Something moving on a cross-member in the open timbers of the ceiling caught my attention. A sedate row of pigeons roosted there shoulder to shoulder, gazing down on to the activity below them. Several children were taking it in turns to run the length of the hall, jumping from one work table to the next, until from the table nearest the front they made a leap of two metres or more, at full stretch, on to the proscenium of the stage, where they landed with a sonorous boom that echoed round the hall as if a drum had been struck. Surprisingly, considering this distraction, most of the students were working, either on their own or conferring with a neighbour. They were painting pictures on large sheets of brown paper.

Lang was standing on his own at a table on the far side of the hall, reading. He had a cigarette notched firmly between his fingers and held close to his face, his eyes tight against the smoke. He was standing side-on to the table, the book pressed down with his free hand, the pages held open with his spread fingers. He looked as though he’d paused to take a quick look at the book on his way to doing something else and become caught up in it. His lips were moving and his body was reacting to the rhythm, or to the sense, of the words.

He didn’t look up as I approached him. I saw he was reading Burns’ Tam o’Shanter. With a mixture of fear and awe and deep fascination, I’d listened as a child to the swaggering tones of this poem more times than I could remember. My father had known by heart every one of its two hundred and twenty-four lines. I’d been exposed to it so often that I’d absorbed entire passages without ever making the effort to do so. At the slightest invocation, it sang in my head with my father’s voice. The mention of something Scottish, and in particular Glaswegian, was sufficient to set off in me a string of stanzas from Tarn.

When I was fifteen I discovered I possessed the ability to reproduce exactly my father’s voice, his thick Glasgow accents and the aggressive manner of his delivery. After I discovered this talent I used to pretend to be my father to my mother. I did it despite misgivings of a preternatural kind, despite feelings that I was invoking something sinister and dangerous and greater than myself, something that I might not be able to control. The compulsion to do it, however, was irresistible. At about the time of day when we were expecting him home from work, when the house was quiet, I’d slam the front door and go into the sitting room and call wildly, Are you there for Christ’s sake Mary?

My mother would come to the door of the passage and look at me with her clear grey eyes. Though I feared them both in different ways, neither of my parents ever punished me. There was a detached fatalism in their attitude to my behaviour, as if they believed that to seek to direct it lay beyond their charter. As if, indeed, we were not a family but were three unrelated people living in the same house.

When my mother saw it was me who had called and not my father, she would return to whatever she’d been doing. At that moment I would sense my father’s presence within me and would fear I had enchanted myself with him. Despite her lack of a reaction, I understood that my mother was quite as disturbed by this trick as I was myself. It drew us into a kind of shared conspiracy against the real man. She never admonished me, even mildly. Her attitude, it seemed to me, implied that if I wished to do such things then I must be prepared to deal with the uncertain consequences myself.

The poetry of Robert Burns was my father’s established way within me, it was his right-of-way, a means by which his personality could flourish in me. When I saw that Lang was reading Tarn I was more dismayed than surprised. I felt offended. It was too personal. Impossible that there could have been any conscious malevolence in Lang’s choice of poem, but I couldn’t see it as mere innocent coincidence. My gaze was drawn along the lines by his moving finger and I heard my father’s voice begin to fill the hall, The wind blew at ‘twad blawn its last; The rattling showers rose on the blast.

The students stopped jumping on to the stage and watched us. Lang turned to me and urged me to continue, his knowing right eye twisted upon me, his nicotine-stained finger pointing at the poem. He took a deep drag on his cigarette and pushed the book towards me. It was an Everyman edition, its green cloth boards sticky-taped to a broken spine. Go on! He exhaled a dense cloud of tobacco smoke, which engulfed me. The students moved in a little closer. They were Lang’s size. He picked up the book and placed it in my hands, then he took a step back and stood among the gathered students.

I looked down at the poem. My father’s voice arose at once within me, loud and arrogant, challenging all authority, a voice beneath which aggression strode in time with the rhythm. An aggression that denounced as weaklings and fools any men who did not partake with him of the superior liberties of the Scots – an option he considered unavailable to women. An aggression directed principally at the English, who’d had the unpardonable audacity to abandon the values of the eighteenth century. The wind blew as ‘twad blawn its last; The rattling showers rose on the blast; The speedy gleams the darkness swallow’d; Loud, deep, and lang the thunder bellow’d …

Fascinated, we listened to the authentic voice of my dead father declaiming the poetry of his imaginary friend and hero, his darkly timbred tone thickening the air of the high cavity of the hall. I could feel his weight above me. A monstrous charge of flesh for the air to carry. Not a tall man but square and solid, heavy and unyielding in thick tweeds and woollens.

After several stanzas the suspended dust caused a stifling tickle in my throat and I gagged on the words, my eyes burning and filling with tears. The students turned away. They’d heard enough. I blew my nose and glanced into the shadows of the ceiling. A figure there foreshortened from beneath, an inverted Dali Christ, my father, dangerous among the old black timbers, the polished studs on the soles of his boots glinting. I wondered how my mother could have remained indifferent, how she’d managed to go on reading her book while he ranted, hobnailed boots and all. I’d made the mistake then of believing it was he who held the key to our share of the magic, not she. For it was he who had freely invoked hobgoblins and apparitions and she who’d eschewed all reference to such things. I’d not recognised his bluster for what it was, nor her unadvertised guardianship of the secret remembrances of childhood.

I sneezed and blew my nose again and wondered if Lang thought I was weeping. He returned from dismissing his class and stood close to me and looked into my face, eager to see what I was feeling. His thick lips were purple and his teeth darkly stained and his short black hair stood straight up from his white scalp as if it were electrified. There was a greedy excitement in his eyes. Come on then, let’s go and get a counter lunch!

I’m not crying, I said. It’s the dust.

Yes, yes, yes! He was exuberant. He made an expansive gesture in the air with his arm extended, as if he would dismiss the dust back to its concealment for me. I shouldn’t let them jump on the stage. This old place ought to be pulled down. He was laughing.

I went with him through rising steam across a concrete yard which had just been hosed and into the pub by the back door. There was a smell of grilling meat and stale beer in the passage. We entered a small back parlour. It was an old-fashioned pub, untouched since the fifties, at which time this room had no doubt been the Ladies Lounge. The tables were topped with thick, scarred brown linoleum. The woman artist, Gertrude Spiess, was sitting at one of the tables on her own. She looked over and waved a magazine at Lang when she saw us come in. There was no one else in the room. Lang introduced us and left us. She offered me her hand. Our fingers touched and we smiled and said hullo and fell silent. Lang had gone to a servery, which framed a portion of the front bar, where there were men gazing upwards to the accelerating voice of a race commentator on the television. Gertrude examined the magazine she’d been reading. I realised she was part Asian.

Lang placed a glass of red wine in front of each of us and sat next to her. Let me see. He took the magazine from her. She watched him closely. He began to read, his lips moving, murmuring the words, at first inaudibly, then more loudly, until we could hear them. ‘Born in the colourful Melbourne suburb of St Kilda in 1946, Gertrude Spiess is an Australian Artist with an intuitive grasp of the significant icon.’ He made an appreciative noise in his throat and took a gulp of wine. There you are then, he said. An intuitive grasp. That means you didn’t have to work hard for it. It’s amazing what they can tell just from looking at pictures. ‘She acknowledges a cultural debt not only to Gabrielle Miinter and the German Expressionists but also to China.’ He paused to take another gulp of wine and to light a cigarette.

She reached for the magazine. Read it later.

He held on to it. Just a minute! He read on, adopting an overly respectful tone, his voice drifting towards parody.

Lang! She warned him.

His voice dropped obediently to a murmur. His lips still moved, however, and I had the impression that the effect of her warning would soon wear off. His eyes glittered with a mischievous, primate quality of cunning.

Observing them, listening to them arguing about the worth of the article in the smart fine-art journal, feeling my presence with them accepted, and beginning to see something of their friendship, I chose to understand them in a certain way. The way I began to understand them offered me the outlines of a story, something to preserve me from certain disenchantment, to save me from the awfulness of reality. Feeling pleasantly woozy from the effects of the wine, it seemed to me that Lang and Gertrude might occupy the vacated homelands of my interior, which were in danger of being colonised by the chanting spectre of my father. Without considering what I was about, I allowed myself to be charmed by the pretensions of this fiction.

After a while, when they had left the magazine aside and he had drunk several glasses of red wine and had begun to be difficult and argumentative with her, I picked up the magazine and read the article.

It was an extended essay in biography and criticism. There was a photograph on the title page: a black and white portrait of her. She was seated on a lacquered ladder-back chair in a room braced with light. She was leaning a little forward, as if she were about to get up and go towards the object of her attention. One pale hand pressed expressively on her thigh, against the rich woven fabric of the black woollen dress. The dress had a wide V neckline. The photographer had achieved the lustrous sheen of soft pencil-modelling on her bare shoulders and bosom. She was looking through the eye of the camera towards the object of her thought. It was a very clever photograph. A skilled photograph. It made of her an important personage: a woman emerged from a deeply textured life into the view of the camera for us to glimpse for a tiny privileged moment, before she was drawn away once again to where our attention could not follow. I felt sure the photographer must be her close acquaintance. A friend. An admirer no doubt. His name appeared discreetly below the lower right hand corner of the picture: Ernst Kuhn. I began to elaborate a circle of such people positioned around her.

The article posed as scholarly, but possessed none of the enthusiasm and generosity one hopes to find in a work of scholarship. It was disappointing. It lacked an ardent desire to share understanding, to bring lucidly before the reader certain precious results of a search for knowledge. It was, in fact, little more than a promotion for a one-woman exhibition of Gertrude’s drawings, which was to be mounted later in the year at a Richmond gallery. There was, however, another, more concealed, meaning to the text, evident in certain passages: ‘The merging of different motif areas in her drawings and the transformation of spatial relationships into flat correspondences gathers towards a distortion of depicted reality and the dissolution of its phenomenal form.’ I didn’t try to reach the sense of this. I understood the point of it was to transpose the locus of authority from the works to the discussion of the works. The writer had assumed the role of validating authority for the images he discussed. In order to do this he had been required to transform what he saw with his eyes into ideologies that he could ‘see’ with his intellect. It was not he or his ideas that interested me. It was the biographical information of his subject:

One cannot speak for long with Gertrude Spiess about her work without hearing from her of her father. The facts are themselves unusual. Gertrude was born when her father was sixty-nine. She never knew her mother and cannot recall a time during the first twenty years of her life when she and her father were apart for more than a few hours. She talks of her work, its sources and its challenges, as if she is referring to a parallel life, as if she is referring to a time and a place where she and her father continue their existence together today. Her unusually close relationship with her father, a gentle and highly cultivated man according to her account, obviously remains the principal source of material for this young artist’s project.

After a lifetime as a bachelor, she informs us, her father never quite recovered from his delight at becoming a father. ‘As a child I always knew myself to be at the centre of his concern. He was very old and I was very young. It was always necessary for us to look after each other.’ She will not discuss his death and refers to herself as ‘the unpunished child’, as if there is a mystery here, the significance of which we ordinary folk will not quite comprehend. One is inclined to believe her.

I became aware that they were waiting for me. Gertrude’s leaving now, Lang said. I returned the magazine to her. I’ll look forward to seeing your drawings. I found myself being examined by her. The pupils of her eyes were a deeply polished black. They were extraordinarily clear and steady. It was not an unfriendly examination.

When she’d gone, Lang leaned over and took my glass. He was shivering. Let’s have one more before we go back, Steven. His smell was of wine and cigarettes and an admixture of the rancid and the perfumed. He rested heavily against me as he got up, and he dragged breath into his lungs as if it cost him a great effort.