9,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

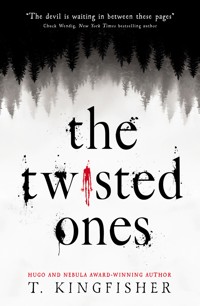

- Herausgeber: Titan Books

- Kategorie: Abenteuer, Thriller, Horror

- Sprache: Englisch

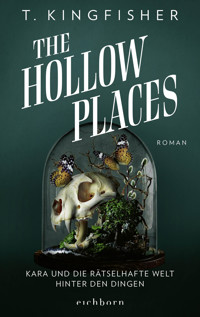

Award-winning author Ursula Vernon, writing as T. Kingfisher, presents a terrifying tale of hidden worlds and monstrous creations… When Mouse's dad asks her to clean out her dead grandmother's house, she says yes. After all, how bad could it be? Answer: pretty bad. Grandma was a hoarder, and her house is stuffed with useless rubbish. That would be horrific enough, but there's more—Mouse stumbles across her step-grandfather's journal, which at first seems to be filled with nonsensical rants…until Mouse encounters some of the terrifying things he described for herself. Alone in the woods with her dog, Mouse finds herself face to face with a series of impossible terrors—because sometimes the things that go bump in the night are real, and they're looking for you. And if she doesn't face them head on, she might not survive to tell the tale.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 484

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2020

Ähnliche

Contents

Cover

Praise for The Twisted Ones

Title Page

Leave us a review

Copyright

Dedication

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

Author’s Note

About the Author

Praise for The Twisted Ones

“Read this one with the lights on”

KIRKUS

“This is righteous, folkloric horror, and the devil is waiting in between these pages”

CHUCK WENDIG, New York Times bestselling author

“With a remarkable assured new voice, Kingfisher strides into the haunted realm of folk horror, and quite simply mic drops”

STEPHEN VOLK, award-winning writer of Ghostwatch and The Dark Masters Trilogy

“Combines dread of the classic Arthur Machen tale with the poignancy of It Follows”

HELEN MARSHALL

“Smart, crackling prose, genuine chills, suspense that doesn’t let up… Definitely not one to miss”

ALISON LITTLEWOOD

“A refreshing contemporary voice, classic scare-filled weirdness… A hugely entertaining read”

ALIYA WHITELEY

t h e

t w i s t e d

o n e s

T. K I N G F I S H E R

TITAN BOOKS

LEAVE US A REVIEW

We hope you enjoy this book – if you did we would really appreciate it if you can write a short review. Your ratings really make a difference for the authors, helping the books you love reach more people.

You can rate this book, or leave a short review here:

Amazon.co.uk,

Goodreads,

Waterstones,

or your preferred retailer.

The Twisted Ones

Print edition ISBN: 9781789093285

E-book edition ISBN: 9781789093292

Published by Titan Books

A division of Titan Publishing Group Ltd

144 Southwark Street, London SE1 0UP

www.titanbooks.com

First Titan edition: March 2020

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

This is a work of fiction. All of the characters, organizations, and events portrayed in this novel are either products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously.

Copyright © 2020 Ursula Vernon. All rights reserved.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A CIP catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library.

For my own two daft hounds

t h e

t w i s t e d

o n e s

1

I am going to try to start at the beginning, even though I know you won’t believe me.

It’s okay. I wouldn’t believe me either. Everything I have to say sounds completely barking mad. I’ve run it through my mind over and over, trying to find a way to turn it around so that it all sounds quite normal and sensible, and of course there isn’t one.

I’m not writing this to be believed, or even to be read. You won’t find me at a book festival, at a little table with a flapping tarp over it, making desperate eye contact with passersby—“Want to read a true story of alien abduction? Want to know the secrets of the universe? Would you like to find out the real truth about the transmigration of souls?” I won’t shove a glossy, overpriced book with badly photoshopped cover art at you, and you won’t have to suffer through my lack of a proofreader.

Truth is, I don’t even know who you are.

Maybe you’re me. Maybe I’m just writing this to get it all out of my head, so that I can stop thinking about it. That seems likely.

All right. I meant to start at the beginning, and already I started babbling about disclaimers and people writing books about crystal power and the secrets hidden in the Nazca Lines.

Let me start again.

My name’s Melissa, but my friends call me Mouse. I can’t remember how that started. I think I was in grade school. I’m a freelance editor. I turn decent books into decently readable books and hopeless books into hopeless books with better grammar.

It’s a living.

None of that’s particularly relevant. The important bit to know is that my grandfather died before I was born, and my grandmother remarried a man named Frederick Cotgrave.

Honestly, I don’t know how she managed to get married once, let alone twice. My grandmother was a nasty, vicious woman. Mean as a snake, as my aunt Kate used to say, which is pretty unkind to snakes. Snakes just want to be left alone. My grandmother used to call relatives up to tell them it served them right when their dog died. She was born unkind and graduated to cruel early.

But I guess a lot of cruel people can pretend to be sweet when it suits them. She married Cotgrave and they lived together for twenty or thirty years, until he died. Every time I went over there, she was snipping at him—snip, snip, snip, like her tongue was pruning shears and she was slicing off bits for fun. He never said anything, just sat there and read the paper and took it.

I never did figure it out. These days, when we know a lot more about abuse, I like to think I’d speak up, say something, ask him if he was okay. But then again, people get into relationships and sometimes they stay there, and for all I know, he got something out of it that the rest of us weren’t privy to.

Anyway, I was a kid for most of it, so it just seemed normal. He was my … stepgrandfather? Grandfather-in-law? I’m not sure which.

That bit galls me to no end. I feel like if he’d been my real grandfather, I would have … oh, not deserved what happened, maybe, but owned it a little. Even if Cotgrave and I had a relationship like a granddad and his granddaughter, I’d have said, okay, maybe I owe him this. But it’s not like he ever took me fishing or taught me how to fix a car engine or whatever bullshit grandfathers are supposed to do. (I don’t know. I didn’t have one on the other side either. My maternal grandmother was a widow, but she didn’t remarry and she spent a lot of time giving money to televangelists and telling other people about Jesus. She also believed in crystal power and aliens, come to think of it, pretty much the same way she believed in Jesus, and never saw any contradiction in the two. People are complicated.)

All I remember about Cotgrave was an old man with no hair, reading the paper and getting snipped at. My dad said he could play a really cutthroat game of cribbage. Maybe that’s why my grandmother wanted to marry him, for his sexy cribbage game. Hell if I know.

The only other thing I remember about him was the sound of a typewriter. He couldn’t type very fast, but I’d hear the noise from his “study,” which was a back bedroom with ratty carpet. Clack. Clack. Plonk. Clack. Screech of carriage return. Clack.

I don’t know when or how he died. I was in college and dead broke and nobody thought I’d come back for the funeral. We weren’t big on funerals in my family. I know some families have these massive orgies of grief, where all the third cousins come back and sob over the casket, but we’re not like that. Everybody gets cremated and then somebody takes the ashes, and after they’ve sat around on the mantelpiece long enough to get creepy, they get dumped in the ocean, and that’s the end of that.

Cotgrave had a funeral, I guess, or a memorial service or something. Aunt Kate told me that a bunch of weird people showed up. “Such odd people,” she said. “I think he might have been in one of those societies. You know, like the Elks or the Freemasons or whatever. They weren’t rude, just odd. Your grandmother was pissed.”

“Grandma’s always pissed.”

“Well, you aren’t wrong.”

Now, of course, I wish I’d known more about the odd people. But I doubt Kate knew anything. She probably talked to all of them and got their life story—she had that ability—but she would have forgotten it as soon as she heard it. Kate was a wonderful sounding board, because she had a memory like a sieve. You could tell her anything you wanted in confidence, and odds were good she wouldn’t remember it an hour later. I lived with Aunt Kate after Mom died, and she really did her best to remember things like doctor visits and parent-teacher conferences, but she wasn’t always great about that either.

Anyway, fast-forward a decade and some change later, and my grandmother finally died. She was a hundred and one. There’s a line of poetry I always think of, though I can’t remember who said it. “The good die first / and they whose hearts are dry as summer dust / burn to the socket.”

Grandma burned to the socket, all right. I didn’t go to that funeral, either. Actually, I don’t think there was one. Dad didn’t have the energy anymore. He wasn’t dying or anything, but he was old—he’d been over forty when I was born, and he was eighty-one now—and he just couldn’t deal with it.

“Not much point, is there?” he said on the phone. “The only reason anyone would show up was to make sure she was actually dead.”

I laughed. Dad didn’t have any illusions about his mother. I still remember when I was young and Mom had just died and he’d asked Grandma to babysit. I marched in that evening and crawled into his lap and informed him that she was mean and I didn’t like her at all.

In another family, I might have been told that I loved my grandmother and was a naughty child. But my father only sighed and rubbed his forehead and said that yes, he knew what she was like, but he didn’t have any other options. He took me to the library that weekend so that I could read in my room, and after a few months of that, I went to live with Aunt Kate.

After I’d finished laughing—not that it was funny, but it was true—I stayed on the line and listened to Dad breathe too hard. His lungs were probably going to be what killed him. They were only a little creaky right now, but you could hear it coming, a rasp down at the bottom that was going to turn into emphysema or pneumonia or just erupt one day into full-blown stage-four lung cancer, no matter how many times the doctors swore that he was clear.

“Her house has been locked up for two years,” he said finally. “Mouse, I can’t handle it. I hate to ask… It’s a shit job, and I know it. I think there’s a storage unit too. Somebody’s gotta clear them out.”

“Sure,” I said, doing frantic mental math about the projects I was working on and how soon I could wrap them up. “Okay. I’ll go down.”

“You sure? It’ll be a mess.”

“It’s okay.”

Dad never asked me for anything, which is why I would have done anything for him.

He sighed. “If there’s anything worth keeping, keep it, or sell it and keep the money. I just want it … dealt with.”

“Are you planning on selling the house?”

He made a short little barking sound that was a laugh or a cough or halfway between the two. “I will if it’s in any condition to sell. It wasn’t good when we put her in the home. It might be really bad. If you get in and it’s a disaster, tell me and I’ll pay for contractors to go in and strip the place down to studs.”

I nodded on the other end of the line. He couldn’t see me, but he could still probably guess. Dad and I had talked on the phone every week since I went to live with Aunt Kate, even in the days when that meant he was paying through the nose for long distance. To this day I think we’re still more comfortable talking on the phone than in person.

Gah. I don’t know why I’m telling you all these details. None of this matters, except maybe the odd people at the funeral.

I wish I knew if there was some reason to write all this down—if including every little detail will make for a better exorcism of the events from my mind, or if I’m just stalling to avoid getting to the hard parts. Like the stones.

I still don’t know how I’m going to explain about the stones.

But I don’t have to write about those just yet, so I’ll just hope that my subconscious knows what it’s doing.

One of the ironies of this situation is that I actually remember thinking, Well, the old bat did me a favor at last.

It was a good time for me to get out of Pittsburgh. I’d had a relationship end rather badly, and—oh, you know how it is. You’re gritting your teeth when you see them together in public and insisting that you’re still friends, while thinking you cheatingsonofabitch behind your eyes and you know that there’s a very good chance that you’re going to start behaving badly.

So I put my dog in the truck and packed up a suitcase full of clothes, asked my aunt Kate to keep an eye on the house, and drove down to North Carolina.

It’s a long drive. It’s pretty, actually, if you go through West Virginia, but of course then you’re in West Virginia. Lots of deep mountain “hollers,” and I guess the etymologists are still fighting over whether the word comes from hollow, which would make sense, or hollerin’, which is a folk-art form where people yodel at one another.

I stopped regularly, both because I was drinking a lot of coffee and to take Bongo out. Bongo’s a redbone coonhound, and he was named after the antelope, not the drum. They’re the same color, and if you’ve ever seen a coonhound run, they bound like an antelope, hence, Bongo.

I have had to explain this more times than I can count.

Bongo’s a rescue. I got him as an adult and he’s starting to go a bit white around the muzzle now. He’s not that smart, but he can detect if a squirrel passed by at any point in the last millennium. There’s a tree in the backyard that he chased a possum up once, and he has visited it faithfully every day for the last two years, on the off chance that the possum has come back.

I have no idea what he’d actually do if he caught a possum—lick it to death, probably. Coonhounds usually get dumped when they turn out not to be very good hunters. Bongo is an excellent watchdog, by which I mean that he will watch very alertly as the serial killer breaks into the house and skins me.

But if the UPS guy ever tries to put one over on us, Bongo’s on the case. If dogs had religion, Satan would be the UPS guy.

(Yes, I own a hound dog and a pickup truck. No, I don’t have a gun rack on it. I fired a BB gun once in Girl Scouts. It went bang and made my hands hurt and that was the end of that.)

Anyway. It’s technically a ten-hour drive, but it takes about twelve when you have a dog and an overactive bladder. We ate at drive-throughs. Bongo got a cheeseburger, which made him think that he was in heaven. (It seems very unlikely that my vet will ever read this, but just in case, this was highly unusual and I do not actually feed him scraps from the table on a regular basis.)

I stayed at a motel that night. I didn’t want to face whatever might be in my grandmother’s house—squatters, or hoarding, or feral cats, or whatever—after a long drive. Dad said he’d had the power turned back on. No Internet, but that’s why God invented cellular data plans.

I wish I could remember what that night was like. I think it was the last one where I was standing over here, with you, on the normal side, and not over there, in that other place, with the white people and the stones and the effigies. And Cotgrave, of course.

But I don’t remember it. It was just one more generic night at a motel. Bongo probably started the night on the other bed, then oozed over and flopped onto my feet, but that’s more because I know what Bongo’s like than because I remember it. (He’s flopped over my feet right now, as I’m typing. Occasionally he looks up sadly at me. It’s a lie; he’s happy as long as he gets fed and people pet him. I wish I were a dog. One of the simple ones, like hounds. Border collies are too complicated. I suspect if I had owned a border collie, this story would have a very different ending, and I probably would not have been around to type it up. But I had Bongo, and he saved our lives because he is simple and made of nose.)

I’m getting ahead of myself again. I’m sorry.

The next morning, I got up and went to go see what kind of mess my grandmother had left behind.

2

“Oh shit,” I said.

I said it a couple of times. There was no human around to hear me.

Then I let the screen door slam shut and turned around and sat down on the steps of the deck.

Grandma had lived about thirty minutes out of Pondsboro, which is southwest of Pittsboro, which is northwest of Goldsboro, because nobody in the late 1700s could think of an original name to save their lives.

North Carolina’s a weird state, because there are all these roads that are framed by trees, and so you literally do not know how remote the area is. You’re just driving through trees. The woods, once you cut them down, grow up again in a dense tangle of kudzu and buckthorn and honeysuckle and loblolly pines. You can’t see through them. At any given moment, you could be surrounded by a thousand acres of uninhabited woods, or you could be thirty feet from a business park full of IT professionals. There’s no way to tell.

Get out around Pondsboro, and you’re more likely to be near the thousand acres of woods. There’s some weird little dips in the landscape—not full hills exactly and nothing you’d call a holler, but things fold over on themselves and wrinkle up and you get weird little bluffs cut by things that are a creek in Pittsburgh and a crick down here. (I usually just call it a stream to save argument.)

Grandma’s house hadn’t been that remote when she’d bought it. There had been a couple of farm families nearby and a pack of hippies across the road. But people left the farm for the city, and the pastures grew up into the tangle of woods I mentioned before, and the hippies got old and most of the kids moved out. I saw a car parked over there when I drove up, but that doesn’t mean anything in the South. It wasn’t up on blocks, though, so maybe someone was still living there.

She’d had nothing kind to say about the hippies, but that was no surprise.

I’d passed one or two trailers on the way up, and there might be more back in the woods. For all I know, I could be surrounded by people.

Sitting on a dead woman’s porch, though, I didn’t much feel like it. I felt like the only other living person on earth was my dad, up north, and the world was empty except for the two of us who had to deal with what my grandmother had left behind.

Bongo was still in the truck. He stuck his head out the window and whined.

I sighed.

I haven’t described the house yet, have I? I probably should.

It was a big old Southern rambler, with a red tin roof. The tin roof was in good shape and the walls were solid, but the white paint was starting to wear off. You could see bits of wood under it. The wraparound porch was weathered gray wood and the steps creaked when I walked on them. There was a carport, but no garage. Somebody had filled the back of the carport with firewood a long time ago. The whole carport had slumped like a badly made cake. I didn’t even think about parking my truck in it.

The underside of the porch roof was painted pale blue. “Haint blue,” they call it. The theory is that if a ghost comes up to the door, it’ll look up and see the blue ceiling and think it’s the sky, and drift up into it. I don’t know how that’s supposed to work. But I’ve also heard that it’s supposed to fool wasps the same way, so maybe wasps and ghosts are getting muddled up there. You don’t want either nesting in the porch, anyhow.

Because it’s the South, there was a thin layer of green algae on all the vinyl surfaces, around the edges of the windows and whatnot. There were long squiggly lines etched through the green, where the slugs had crawled at night. There’s not much you can do about either one, except scrub things off with bleach occasionally.

Nobody had been through here with bleach for a long time. The porch was covered in all the usual yardwork detritus—a rake and a trowel and a faded bag of fertilizer granules. An old pair of gloves lay discarded on the rocker. (Of course there was a rocking chair. I told you we were in the South.) Everything was tied together with ropes of cobwebs. The rake handle was practically glued to the porch supports. It was one of the ones with a hollow metal handle, and there was a big web right around the end, which meant that there was a spider living in the handle.

I made a mental note to buy a new rake. That one belonged to the spider now.

None of this was why I’d started swearing.

I swore because when I unlocked the front door and opened up the house, the light fell on a stack of newspapers.

Behind it was another stack of newspapers. Behind that was another stack. They were tied up neatly with string, and there was a pile of magazines next to that, and another pile, and another, and oh shit Grandma was a hoarder.

I took a deep breath and scrubbed my face with my hands.

Maybe it wasn’t as bad as I feared. Maybe it was just one room.

It’s never just one room, my brain said, and of course it isn’t, but maybe just this once…

Yeah, no. It wasn’t just one room.

It wasn’t … It wasn’t awful. She didn’t collect cats, thank God, so the house hadn’t turned into one of those horrible biohazards with urine on every surface and burying beetles scuttling under the furniture. And she wasn’t the sort of person who hoarded food, so there wasn’t two-year-old garbage everywhere. Dad had taken the trash out when he took her to the home, and then he’d come back and emptied out the refrigerator.

He hadn’t defrosted the freezer. I could tell by the dried circle of water stains on the floor, where it had leaked out when the power was shut off. But honestly, if you have to take your ninety-nine-year-old mother out of her house and put her in a home while she’s calling you every name in the book, I’ll cut you some slack on remembering the freezer.

(He never said that she called him every name in the book. I’m just assuming on this one.)

Still, it could have been worse.

The newspapers were piled up and magazines were stacked five feet high, but you could still get to the living room furniture. There were places to sit. When I flipped the light on, it looked like a very cluttered room, not like an alien topography.

The place was a terrible firetrap, though. All that paper everywhere. It was a miracle Grandma hadn’t burned the place down by accident.

(Oh God, if only! I don’t wish even an evil old bat like her to die by fire, truly I don’t, but if she could have passed peacefully in her sleep and then the house burned down a couple of hours later, that would have been fine. And I’d still be able to sleep at night.)

The hoard was somewhat organized, I’ll give her that. I went from room to room, listening to the floorboards creak. There were narrow paths between the stacks. Magazines and newspapers in the living room, Tupperware and bags full of other bags in the kitchen.

It got worse as I got farther back in the house, though. The bathroom was a jumble of ancient shampoo bottles and body lotions with the caps melted on. The toilet … well, pray God the well pump had survived the years of inactivity without locking up.

The stairs to the second story were completely jammed with garbage bags. I prodded one with my foot. The contents moved like cloth but smelled like mice.

One of the closet doors was wedged open. The inside was a solid block of Christmas decorations, old coats, and unlabeled white jugs. The tiny bit of floor that I could see had a white crust over it where the jugs had leaked.

There were three closed doors off the hallway that probably led to bedrooms. I had originally been planning on sleeping in one of those bedrooms, but Christ only knew what was being stored in them.

The whole place stank of must and mice and silence.

Bongo barked. The noise jerked me out of my increasing despair, and I went back outside. It was an overcast day, but the sky seemed very bright.

I let Bongo out of the truck and grabbed his leash. You can’t let coonhounds off the leash, not ever. They’ll smell a rabbit and wind up in the next county. I owned more ropes and harnesses and tie-outs and carabiners than a dedicated bondage enthusiast.

(Okay, okay, fine, I’ve heard of dog owners who have hounds that are so responsive that they will heel beautifully with no lead at all. Those are smarter owners than me and smarter dogs than Bongo. But we do fine by each other, and that’s the important thing.)

Bongo went sniffing and snuffling around the edge of the porch, over into the bushes, back to the porch. I let him follow his nose. I didn’t have anywhere to go and I didn’t want to open one of those bedroom doors before I absolutely had to.

We went over to the carport. The woodpile in the back was probably at least 80 percent spiders at this point, and shared space with a generator that dated from the Nixon administration. I looked up the side of the house, to the windows on the upper story, and I could see something pressed against them—boxes, maybe, or furniture.

Two stories’ worth of stuff. I let out a heartfelt groan, and Bongo looked back to make sure he wasn’t doing anything wrong.

“It’s not you,” I told him. “You’re fine.”

He peed on the woodpile by way of agreement and ambled around the back of the house.

The porch wrapped clear around to the back, on three sides. The back section was screened off to keep bugs out, but there were holes in the screen where something had gotten in.

Bongo went immediately on alert, which probably meant that the holes were from squirrels.

Trees pressed in on three sides of the garden: loblolly pine and pin oak and tulip tree. (Aunt Kate is a botanist. When I was growing up, she would constantly interrupt herself to reel off the names of passing plants. As a result, I can follow extremely fractured conversations and I also know common trees on sight the way most people know dog breeds.) There were some saplings making inroads around the edges, and the grass had grown high and rank in sunny spots. The shrubbery was too dense to walk through in most places, but the right-hand corner, under the oak, was nothing but dead leaves. The woods behind it hadn’t been cleared recently, because I could see quite a way back there, before a stand of holly trees blocked the view.

Mostly I saw even more dead leaves and a couple of large rocks. Not exciting for anyone, except possibly Aunt Kate.

The backyard had contained a garden at some point, and bits of the deer fence were still there. The fence posts leaned drunkenly, with chicken wire bunched up between them. Mint and oregano had run riot everywhere, and every step we took kicked up a delicious smell.

I had a strong urge to pull some of the weeds, but I wasn’t here to garden. Pity. I might have enjoyed putting the garden to rights. More than I would enjoy excavating the house, anyhow.

How had I not known she was a hoarder?

I’d only been a kid when I’d visited, but kids remember things. There hadn’t been the piles of newspaper then. The counters in the kitchen had appliances, not stacks of Tupperware.

A memory surfaced of Grandma washing Ziploc bags and drying them with a hair dryer. Dad saying, “She grew up during the Depression, Mouse. A lot of folks who lived through that have a hard time throwing anything away.”

Well. The signs had been there. And sometime in the last decade or two, she’d just … gone over the edge.

I pulled out my phone and looked at it, thinking of calling Dad. He could have warned me.

He did say it was a mess. And that it was bad.

Yeah, but his definition of a mess and mine are apparently a lot different!

There was no cell signal. I cursed my carrier and shoved the phone back in my pocket.

If you’re thinking that she was going mad in the house alone for forty years, like Miss Havisham, don’t. Dad paid for caregivers, and he went down to visit her fairly regularly when he was still able to get around. But the caregivers got harder and harder to find as she drove them off, and eventually there was just the woman who took her into town.

Maybe that’s when it got bad. Maybe that woman didn’t go into the house. Maybe nobody’d known the state the place was in.

Bongo wanted to go under the porch steps. “No, buddy,” I said, leading him past. He looked longingly at the hollow under the stairs. There might be a possum he could lick!

“I know,” I said. “I’m the worst.”

We finished our circle around the house. There was a set of double doors that probably led down to a root cellar. Jesus. Who knew what I’d find down there?

Bongo’s tail was wagging good-naturedly as we finished the circuit. One of his ears had flipped over along the way.

“Let me fix your ear…” More wagging.

I tied him out to the railing on the front steps. He could probably find a way to twist the leash around, but I wasn’t going to be more than thirty or forty feet away. And anyway, I suspected that I’d be coming out of the house frequently, just to be surrounded by clean air instead of junk.

He flumped down on the porch and looked tragically at me. I gave him a chew toy, and he began gnawing on it and making terrible canine faces of pleasure.

You know, thinking about it now, if Bongo had been scared of the house, I might have left. I was right on the edge. I could have called Dad and said it was beyond my ability, it was too full, it was a mess, and he should just hire one of those companies that deal with hoarder houses and get them to drag it all to a landfill.

But Bongo thought the place was grand. There were things to sniff! There might be squirrels! And I hadn’t seen anything terrible yet, just stuff. Nothing I couldn’t fix with a couple hundred garbage bags and directions to the county dump.

I had a pickup truck. I had a lot of irritation at my recent ex to work out, ideally with manual labor. I might as well give it a try.

Which just goes to show that my dog and I were both as sensitive to that other world as rocks, and probably that we deserve each other.

* * *

I went back into town to get garbage bags and a couple pairs of sturdy gloves. Pondsboro actually has a little downtown. They’d love to be like Southern Pines, two hours away, which is so quaint it makes your teeth hurt. The rich country-club people all go there to spend money, so you can have antique stores instead of junk shops and a really good independent bookstore and little shops that sell nothing but scented candles and fancy doorknobs.

Southern Pines is in the Sandhills, though, and it’s a lot easier to put a golf course there. So Pondsboro’s downtown isn’t nearly as ritzy, despite their best efforts. But they do have a good coffee shop and a bad diner and a hardware store that hasn’t been eaten by one of the big chains. I went to that last one for garbage bags and gloves and about a dozen containers of those little bleach-soaked wipes. (And, yes, a scented candle. It didn’t matter what it smelled like; it was bound to be better than the smell of musty house.)

I picked up a cheap pair of sheets, too. They were red flannel, with a Christmas-tree pattern, and since it was now late March, they were on deep, deep clearance. I felt weird enough about sleeping in a dead woman’s house without sleeping on her sheets. Even if I found a clean set in a closet, they would smell like the house or (worse) like her. I’d rather have Christmas trees.

The barista at the coffee shop was a cheerful Goth woman with hair dyed black in back and hot pink in front. She skillfully extracted the reason I was in Pondsboro, how long I was staying, and who my grandmother was.

“Oh!” she said, when I said her name. “Old Mrs. Cotgrave? She’s dead?”

“Hard to believe, isn’t it?” I said into my latte.

“She used to come in here. She was … ah …” I could see her trying to decide whether or not to be diplomatic.

“A raging bitch, I imagine,” I said. “I’m sorry.”

The barista grinned. “Well, yes. And a lousy tipper.”

“I’m sorry about that, too.” I sighed. “It wasn’t just you. She was an awful person.”

“Some people are,” she said sympathetically, and gave me a warm-up on the latte when I got up to leave.

I made a mental note to come back, and not just because the coffee shop had Wi-Fi.

Bongo enjoyed the drive back. He stood with his front feet on the central armrest and gazed out the front.

“If I get in an accident, you’re gonna go right through the windshield, you know.”

He ignored this. I looked in the rearview mirror and got a great view of the dog’s forehead.

Once we got back to the house, I let him come inside with me.

He walked around, sniffing. The smell of mice was much too exciting, and I had to haul him away from the bags on the staircase.

Oh well. It’s not like he can make much more of a mess…

I pulled on the gloves. They were good solid work gloves, men’s size medium, not the crappy little floral-print things they try to sell to women. With the gloves and the trash bags, I felt obscurely armored. Whatever horrors awaited, at least I wouldn’t have to touch them.

I lit the scented candle. It was called “Berries and Dreams,” and I am sad to say that it had been the best of the selection and the only one that did not involve patchouli in some fashion. It smelled like the lip gloss I’d worn in third grade—strawberry with notes of wax.

It was still better than mouse crap.

* * *

My first order of business was to find a bedroom. I was waiting on e-mails to be able to work on an editing job, so I wasn’t losing money at the moment, but if I had to spend the whole time in a motel room, I’d start burning the bank account at both ends. Motels that allow dogs charge a lot of money for the privilege.

The door at the back of the hallway had boxes piled to knee high in front of it, so I wasn’t hopeful about it, but the other two were reasonably clear. There was a rampart of plastic storage bins between the two doors, reaching to the ceiling, but you could get by them if you turned sideways.

I pulled open the first door and then slumped against the doorframe with a groan.

Christ. The doll room. I’d forgotten all about that. She’d had those awful china dolls with the painted eyes, which were bad enough, but she’d really liked the newborn dolls. The ones all made up to look like realistic babies, except that when something’s that realistic, it just looks dead.

The whole damn room was full of dead babies. Most of them were still in boxes, but she’d taken a bunch out, too. Then she’d stacked the other dolls in front of them, so all you’d see were horrible hyper-realistic faces peeking out from behind the edges of boxes or piled together. It looked like a monument to infanticide, and also to the astonishing holding capacity of clear plastic bins.

On the far side of the room, over the sea of babies, was a tall built-in storage cabinet, running to the ceiling. The china dolls stood inside that, in their little shoes and little coats, their hair dusty and immaculate.

I remembered her taking me into the room—you could see the floor then—and showing me the dolls and then telling me sternly that they were not for playing. I can still recall feeling embarrassed and resentful about it, because I wouldn’t have wanted to play with her stupid dolls anyway. I much preferred stuffed animals, and china dolls are creepy no matter what age you are.

They hadn’t gotten any less creepy. They stood in the case like objects of worship, surrounded by infant sacrifices.

There is probably a sum of money that could have incited me to sleep in that room. I am not wealthy and I can be bought. But it would be up in the thousands. I’m easy, but not cheap.

Since no one was appearing to proffer large sums of money, I shut the door to the room again and leaned against it, shuddering.

The old woman, wandering around the house for years, buying dolls that looked like infants. For the first time I started to feel a little guilty.

Possibly you think that I should have been feeling guilty long before this. Maybe you think I’m a terrible person. My grandmother, after all, had lived alone for years and had died unloved. She was my blood kin. I should have been coming down to visit her, and … I don’t know, reading aloud to her or something.

That seems like it would have been an excellent way to get a book thrown at my head.

You have to understand, it’s just not how my family works. We don’t stay where we aren’t wanted. Grandma had made it clear that she wanted nothing to do with me, and if somebody wants nothing to do with you, you leave.

We are a family that divorces quietly and without contest. If someone says they are done with us, we take them at their word.

But the corollary to that, I suppose, is that we return just as quickly and with just as little fanfare. My dad and my stepmother, Sheila, were separated for nearly seven years, and then one night she called him up and said, “Please come get me.” And he did, and they’ve been together ever since. I resented that at the time, but she takes good care of Dad, and after a while that was the only thing that mattered.

If Grandma had called me up in the middle of the night, at any time in all those years, and said, “Mouse, I need you here,” I would have come. I would have gotten in the car and driven all night. I didn’t like her and I didn’t love her, but I would have come because she’d asked.

But she never asked.

Should I have known somehow? But I hadn’t seen her since I was seven and she babysat me after my mom died, when Dad couldn’t afford a sitter. That had been so sufficiently awful that I’d been relieved to go live with my mom’s sister, Aunt Kate, even if it meant that I saw Dad only on weekends. I hadn’t spoken to her since I was seventeen and called her to ask if she wanted to attend my high school graduation.

She had snorted at me and said that she didn’t know why I was bothering to graduate. I was Catholic trash and was just going to get married and squeeze out babies for the rest of my life.

I remember that very clearly, mostly because it was so odd. Yes, I was Catholic, more or less, but that just meant that Aunt Kate had saint cards shoved in the edges of the bathroom mirrors and that we went to Mass on Easter. (We hadn’t managed Christmas Mass in years.) I had never been confirmed, never gone to confession, couldn’t say a Hail Mary if my life depended on it.

I wasn’t offended. I wasn’t even angry. It didn’t make sense. Grandma might as well have yelled at me for being from Pennsylvania, or for having wavy hair, or for walking upright instead of on all fours.

I took the phone away from my ear and stared at it, baffled. I could hear her still talking, tinny and distant through the receiver. Then—this was in the days of landlines—I set it back in the cradle and shook my head.

If you think that I’m harboring some deep resentment here, I’m really not. I’d called because Aunt Kate had said, somewhat doubtfully, that I should. I hadn’t thought about her in years. She didn’t do holidays. She was more like a particularly unpleasant teacher remembered from my grade school years than a relative.

She’d obviously wanted nothing to do with me. So it had seemed the polite thing to do was to oblige.

I don’t know. All I know is that she never asked for anything. Maybe it’s genetic in my family. Dad never asked for anything, so now that he had, I’d move heaven and earth if I needed to.

And that’s why I was here, in this horrible house stuffed full of baby dolls and ancient Tupperware and mouse-stained clothes, because he’d asked.

Perhaps I am a terrible person, but give me what little credit I deserve.

I was here.

* * *

The second door was not as viscerally unsettling. Not many things could be. Even a roomful of taxidermy would be less creepy, and Grandma wasn’t into taxidermy.

Nevertheless, it was a sad room, and that’s because it was her bedroom.

There was a road through the piles of boxes. The bed itself was covered in old clothes and newspapers, but I could see a deep hollow where she’d slept, the sheets bunched up around it. It hadn’t come out, even after two years of absence. Clothes lay draped over every surface, interspersed with boxes of coat hangers. The closet had a folding door that had come off its track, but was held in place by a tower of shoe boxes.

There was a large box next to the door, unopened. The outside proclaimed it as a foolproof closet-organization method. The bottom was stained where water had soaked into it, or maybe it was mouse urine. I made a noise in my throat—I couldn’t tell you whether it was a laugh or a sob—and I shut the door again.

I decided that if the third door didn’t work, I’d sleep on the couch. I could have cleared off that bed, but it would have been like sleeping in my grandmother’s grave. Even though she’d died hundreds of miles away, in a home, with my father checking on her all the time, I felt her presence in that room.

If she was a ghost, she would be an unquiet one.

The third door took some work to get to. I nearly abandoned the attempt—if the hallway was this clogged, the room was probably wall-to-wall boxes of Ziploc bags and commemorative plates.

I started to push the boxes out of the way but felt a stab of guilt. Moving boxes around inside the house wasn’t going to help. So I picked up each one and dragged it into the living room.

One was full of coat hangers. That went in the back of the truck immediately. One was full of papers, but a quick look told me they were all coupons and PennySaver mailings turning yellow-gray with age. I riffled it briefly, but no stock certificates fell out.

Well, a woman can dream.

There was a stack of empty shoe boxes all wedged together, which went out. One of the bottom boxes had a shoe. It was not a very good shoe.

At the very bottom was a carpet steamer. Thankfully it had wheels, because I could barely lift the thing. I dropped it on my foot getting it down the porch steps, and Bongo was treated to the sound of me swearing a blue streak.

“Hrooof!” he said.

I ignored this commentary on my language and wrestled the carpet steamer into the back of the truck at great personal cost to my back.

At last the door was clear. It stuck when I tried to open it, as if it had not opened for a long time, but I wedged my foot against the bottom and pushed.

It swung inward.

Into a nearly empty room.

After my first, astonished glance, it became obvious that the room wasn’t quite empty. It had a bed and a nightstand and a chair. There was a painting over the bed and a few framed photographs on the walls.

But compared to the rest of the house, it seemed absolutely bare. The hardwood floor had a thick layer of dust, but no boxes piled in it. The mice had come in, found nothing of interest, and left again.

“Oh…” I said out loud. “Oh, right.”

It was Cotgrave’s room. Of course.

He had died so long ago. I suppose I had thought that she would clear it out, use it as storage. And yet it was empty. Sheets had been turned back on the bed, as if someone had just gotten up. Except for the layer of dust, it could have been abandoned only an hour before.

It hadn’t occurred to me as a child that my stepgrandfather’s den had been his bedroom as well. That he had not been sleeping in a bed with my grandmother when he died.

I wonder if they started that way, or if he moved out eventually.

Well. The vagaries of Grandma’s second marriage were not my concern, and probably none of my business.

“But it does make my life easier,” I told the absent Cotgrave. (It was easier to talk out loud. It made some sound in that house, which was much too quiet, except for mice and Bongo working on his chew toy on the porch. I really needed to buy a radio or something.) “Replace the sheets and a normal person can sleep in here.”

I went to the window and opened it. The wood had swollen, but after some banging, much like the door, I managed to push it open. The screens were still intact.

Bongo sat up and came over to the window. He licked the screen and seemed puzzled that it tasted like wire.

“You’re not smart,” I told him. He wagged his tail and licked the screen again, on the off chance that it had become tasty.

I opened the nightstand drawer. It was full of the usual detritus that accumulate in drawers—old tweezers, broken nail clippers, the warranty for a piece of electronics that had stopped functioning years ago. There was a black book on top, with an elastic ribbon holding it closed.

I flipped the book open. It was probably just an address book, but just in case there were any hundred-dollar bills tucked between the pages…

There weren’t. It was full of handwriting instead.

I almost threw it away. I had the mouth of the garbage bag open and was moving my hand toward it when a phrase jumped out at me.

She has hid the book.

I had to read it twice to make sure I was right the first time. Whoever wrote it had neat-enough handwriting, but it was tightly slanted and the s’s and the a’s looked nearly identical.

That’s wrong, I thought. It’s either she hid the book or she has hidden the book. Pick one and commit.

Like I said, I’m a freelance editor. The Chicago Manual of Style is tattooed on my soul. I’m pretty lenient about these things when editing fiction—show me a character who uses “whom” correctly and I’ll show you a real prat—but she has hid the book? No.

The next line was I’m afraid she might have destroyed it, but there are no fresh ashes in the burn barrel. I went through the trash, but it was not there. It must be hidden. I asked her where it was, and she asked had I lost something, but there was that look in her eyes like when she hid my keys.

I sat down on the bed. Good God, was this Cotgrave’s? And was she my grandmother?

I could easily believe that Grandma would hide something and take pleasure in the other person looking for it. There’s mean and then there’s pathological. Once you start calling up people to laugh when their dog dies, you’re way over on the pathology side of the equation.

On the other hand, Cotgrave had been getting on in years himself, and lots of old people get paranoid that other people are stealing things from them. I couldn’t swear that Grandma was doing any such thing just because she was a nasty piece of work in other regards.

I flipped to the next page.

Still can’t find the book. Checked all the shelves. Shades of the Purloined Letter.

I won’t leave without it. It’s the last I’ve got of Ambrose.

Cotgrave was clearly a trusting soul. He’d left the journal in his nightstand, and if Grandma was hiding his stuff, you’d think he’d realize she was probably reading this. Poor guy.

I turned the page again. They were old and stuck together, so I had to tug my glove off to do it.

It’s in my head again, like a song that keeps replaying. When that happens, I read it in the book, and that makes it stop, but now I can’t.

This must be what going mad feels like.

I made faces like the faces on the rocks, and I twisted myself about like the twisted ones, and I lay down flat on the ground like the dead ones.

That seems to have helped. Maybe if I read it written here, it’ll stop.

At first I thought that this was the moment when it all went bad. If I had shoved the book in the garbage bag before I read that, maybe it would have come out differently. If my stupid editor brain hadn’t kicked in when I had opened the journal, maybe I would have been able to walk away.

I can see myself, when I think of this: sitting on the bed, one leg tucked up under myself, the garbage bag draped over my other knee. I see myself from the outside, like a stranger—woman in her midthirties, gaining weight no matter how often she takes the dog out jogging. Wavy brown hair, with a few strands stuck to her forehead and dust smudged across her face.

And in her hand, the little black journal.

But now, writing this, I think maybe it wouldn’t have mattered. I was there, and I was not going to leave until I had cleaned the place out. Maybe everything would have happened anyway, and I would have had no map to guide me—even as poor and addled a map as Cotgrave’s journal proved to be.

At the time, though, I had no presentiment. I read that passage and what I thought was, Ugh! That’s kind of creepy! Twisted myself about like the twisted ones … yeesh.

It was a weird thing to find written in a book by an old man who liked cribbage and read the newspaper for hours a day.

“It’s in my head again, like a song that keeps replaying…” Sounds like he’s talking about an earworm. Poor soul.

Lord knows I’d had songs stuck in my head before. TV theme songs were particularly bad. One time I wandered around for nearly two weeks humming the theme to Cheers, until I had to sit down and actually watch an episode or go barking mad.

This didn’t seem much like a song. Then again, I’ve known people who get poetry stuck in their head. My college roommate used to recite Poe’s “Eldorado,” and I don’t think she even knew she was doing it sometimes.

Of course, she was an English major.

I didn’t have time to keep reading a journal—I had a house to clean. I set it down on the nightstand and finished emptying the drawers.

The closet was as bare as the rest of room. A few suits of clothes. A pair of bedroom slippers and a pair of scuffed leather shoes. Three Time Life books on World War II, but that probably didn’t mean anything. Books on World War II appear spontaneously in any house that contains a man over a certain age. I believe that’s science.

On the far side of the top shelf was an ancient manual typewriter. I groaned. It had to weigh a ton. Just looking at it made my back hurt. I was going to have to get on a chair, lift it out at shoulder height, and probably drop it on my foot in the process.

Well, that was a concern for another day. I stuffed everything I could lift into the garbage bags, stripped the bed, and hauled the bag out to the truck.

“C’mon, Bongo. Let me show you the new digs…”

Bongo seemed cautiously pleased. He got up on the bed and made putting the sheets on extremely difficult, anyway.

I resigned myself to the red Christmas-tree sheets smelling like hound. Most of my stuff does.

“For my next trick,” I told him, “I’m going to see if I can’t excavate a counter in the kitchen.”

He accompanied me to the kitchen, discovered that I wasn’t doing anything that would result in dog treats, and slumped to the linoleum with a tragic sigh. Unfortunately, there was only one bare patch of linoleum, so I was stepping over him every time I turned around.

“You’re not helping.”

He let out another sigh. Occasionally my dog sounds like he is deflating.

I tried to sort Tupperware for about five minutes. Then I gave up and just swept the stacks into garbage bags. Bags full of wadded-up plastic bags got the same treatment. (I can see the reason for keeping plastic bags around, but my grandmother had more than her own body weight in the things.)

I tried to think of a song to sing. I really had to get a radio for in here. The house was too quiet.

And I twisted myself around like the twisted ones…

That wasn’t a song.

I dismissed it and started the first song I could think of, which was one we sang at camp approximately a thousand years ago.

“I woke up Sunday morning, I looked up on the wall, the beetles and the bedbugs were having a game of ball…”

Bongo let out another sigh from the bottom of his toes.

I worked my way through the vast number of verses, including the one about dying in a sewer that the counselors wouldn’t let us sing, and cleared a counter back to something that was probably a toaster. Corrosion had sealed it to the countertop. There was a fork sticking out of it, which seemed like a generally bad idea. Fortunately, the electrical cord had rotted through, so the toaster was harmless. I was a little more concerned about the cord that was still sticking out of the wall socket.

There were two microwaves stacked on top of each other. One looked to be made of plastic and one looked like it was made to withstand the atomic bomb.

Somehow I got about half the kitchen counters cleaned without electrocuting myself. The metal microwave was incredibly heavy. I made a mental note to go rent a handcart. I also uncovered a mouse nest and about twenty containers of ant poison, which sealed my resolve not to let Bongo run around loose in the house.

I opened the refrigerator. It looked very dirty, but the air inside was cold. I dithered over scrubbing it out—did it matter? It was ancient, and I was here to throw things away—but eventually decided that I didn’t want my food to sit in a fridge that was covered in stains and mold.

It occurred to me, somewhat belatedly, that there’s a disease you get from mold that lives in closed-up refrigerators. But I was down on my knees wielding little green scrubby pads, and whatever it was, I was probably thoroughly exposed. So, y’know. Oh well.

By the time I finished with the fridge, it was getting dark. I got back in the truck and drove into town for a drive-through meal eaten in the car. Bongo got another illicit cheeseburger. I would have to pick up groceries tomorrow, but the idea was exhausting.

We went back … well, home is the wrong word. We went back, anyway. I’d left the porch light on and most of the lights in the downstairs. From outside, it looked almost like a normal house with warm light spilling through the windows. Moths banged at the porch light.

I sat in the car so long, looking at the house, that Bongo got bored and began chewing on his nails. So I sighed and pulled the keys out of the ignition and grabbed my suitcase out of the back seat. “C’mon, boy. Let’s go.”

Clutter aside, the house seemed solid enough. Probably wasn’t going to fall down on my head. If I could just clear the junk out, we could put it on the market. Dad had made noises about splitting the money with me, and I sure wasn’t in a position to turn money down.

I told myself all this three or four times as I slogged up the steps, Bongo yanking at the leash.