9,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

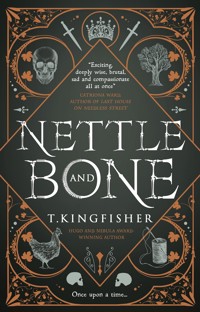

- Herausgeber: Titan Books

- Kategorie: Fantasy und Science-Fiction

- Sprache: Englisch

Instant USA Today & Indie bestseller. Fans of Madeline Miller, Leigh Bardugo and Alix E. Harrow will love this Hugo Award-winning dark and compelling fantasy about sisterhood, impossible tasks and the price of power. WINNER OF THE HUGO AWARD FOR BEST NOVEL 2023 After years of seeing her sisters suffer at the hands of an abusive prince, Marra—the shy, convent-raised, third-born daughter—has finally realized that no one is coming to their rescue. No one, except for Marra herself. Seeking help from a powerful gravewitch, Marra is offered the tools to kill a prince—if she can complete three impossible tasks. But, as is the way in tales of princes, witches, and daughters, the impossible is only the beginning. On her quest, Marra is joined by the gravewitch, a reluctant fairy godmother, a strapping former knight, and a chicken possessed by a demon. Together, the five of them intend to be the hand that closes around the throat of the prince and frees Marra's family and their kingdom from its tyrannous ruler at last.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 407

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Ähnliche

CONTENTS

Cover

Also by T. Kingfisher and available from Titan Books

Title Page

Leave us a Review

Copyright

Dedication

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

Author’s Note

About The Author

Also by T. Kingfisher and available from Titan Books

The Twisted Ones

The Hollow Places

What Moves the Dead (coming soon)

LEAVE US A REVIEW

We hope you enjoy this book – if you did we would really appreciate it if you can write a short review. Your ratings really make a difference for the authors, helping the books you love reach more people.

You can rate this book, or leave a short review here:

Amazon.co.uk,

Goodreads,

Waterstones,

or your preferred retailer.

Nettle & Bone

Hardback edition ISBN: 9781789098273

E-Book edition ISBN: 9781789098280

Published by Titan Books

A division of Titan Publishing Group Ltd.

144 Southwark Street, London SE1 0UP

www.titanbooks.com

First Titan edition: April 2022

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

This is a work of fiction. All of the characters, organizations, and events portrayed in this novel are either products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead (except for satirical purposes), is entirely coincidental.

© Ursula Vernon 2022. All Rights Reserved.

Ursula Vernon asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A CIP catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library.

dedicated to Strong Independent Chicken, a bird in a million

1

The trees were full of crows and the woods were full of madmen. The pit was full of bones and her hands were full of wires.

Her fingers bled where the wire ends cut her. The earliest cuts were no longer bleeding, but the edges had gone red and hot, with angry streaks running backward over her skin. The tips of her fingers were becoming puffy and less nimble.

Marra was aware that this was not a good thing, but the odds of living long enough for infection to kill her were so small that she could not feel much concern.

She picked up a bone, a long, thin one, from the legs, and wrapped the ends with wire. It fit alongside another long bone—not from the same animal, but close enough—and she bound them together and fit them into the framework she was creating.

The charnel pit was full, but she did not need to dig too deeply. She could track the progression of starvation backward through the layers. They had eaten deer and they had eaten cattle. When the cattle ran out and the deer were gone, they ate the horses, and when the horses were gone, they ate the dogs.

When the dogs were gone, they ate each other.

It was the dogs she wanted. Perhaps she might have built a man out of bones, but she had no great love of men any longer.

Dogs, though . . . dogs were always true.

“He made harp pegs of her fingers fair,” Marra sang softly, tunelessly, under her breath. “And strung the bones with her golden hair . . .”

The crows called to each other from the trees in solemn voices. She wondered about the harper in the song, and what he had thought when he was building the harp of a dead woman’s bones. He was probably the only person in the world who would understand what she was doing.

Assuming he even existed in the first place. And if he did, what kind of life do you lead where you find yourself building a harp out of corpses?

For that matter, what kind of life do you lead where you find yourself building a dog out of bones?

Many of the bones had been cracked open for marrow. If she could find two that went together, she could bind them back to wholeness, but often the breaks were jagged. She had to splint them together with the wires, leaving bloody fingerprints across the surface of the bones.

That was fine. That was part of the magic.

Besides, when the great hero Mordecai slew the poisoned worm, did he complain about his fingers hurting? No, of course not.

At least, not where anyone could hear him and write it down.

“The only song the harp would play,” she crooned, “was O! The dreadful wind and rain . . .”

She was fully aware of how wild she sounded. Part of her recoiled from it. Another, larger part said that she was kneeling on the edge of a pit full of bones, in a land so bloated with horrors that her feet sank into the earth as if she were walking on the surface of a gigantic blister. A little wildness would not be out of place at all.

The skulls were easy. She had found a fine, broad one, with powerful jaws and soulful eye sockets. She could have had dozens, but she could only use one.

It hurt her in a way that she had not expected. The joy of finding one was crushed easily under the sorrow of so many that would go unused.

I could sit here for the rest of my life, with my hands full of wire, building dogs out of bone. And then the crows will eat me and I will fall into the pit and we shall all be bones together . . .

A sob caught in her throat and she had to stop. She fumbled in her pack for her waterskin and took a sip.

The bone dog was half-completed. She had the skull and the beautiful sweep of vertebrae, two legs and the long, elegant ribs. There would be at least a dozen dogs in this one, truly—but the skull was the important thing.

Marra caressed the hollow orbits, delicately winged in wire. Everyone said that the heart was where the soul lived, but she no longer believed it. She was building from the skull downward. She had discarded several bones already because they did not seem to fit with the skull. The long, impossibly fine ankles of gazehounds would not serve to carry her skull forward. She needed something stronger and more solid, boarhounds or elkhounds, something with weight.

There was a jump rope rhyme about a bone dog, wasn’t there? Where had she heard it? Not in the palace, certainly. Princesses did not jump rope. It must have been later, in the village near the convent. How did it go? Bone dog, stone dog . . .

The crows called a warning.

She looked up. The crows yammered in the trees to her left. Something was coming, blundering through the trees.

She pulled the hood of her cloak up over her head and slid partway down into the pit, cradling the dog skeleton to her chest.

Her cloak was made of owlcloth tatters and spun-nettle cord. The magic was imperfect, but it was the best she had been able to make in the time that she had been given.

From dawn to dusk and back again, with an awl made of thorns—yes, I’d like to see anyone do better. Even the dust-wife said that I had done well, and she hands out praise like water in a dry land.

The cloak of tatters left long gaps bare, but she had found that this did not matter. It broke up her outline so that people looked through her. If they found some of the bands of light and shadow lay a little strangely, they never stayed long enough to puzzle out why.

People were remarkably willing to dismiss their own sight. Marra thought perhaps that the world was so strange and vision so flawed that you soon realized that anything and everything could be a trick of the light.

The man came out of the trees. She heard him muttering but could not make out the words. She only knew it was a man because his voice was so deep, and even that was guesswork.

Most of the people of the blistered land were harmless. They had eaten the wrong flesh and been punished for it. Some saw things that were not there. Some of them could not walk and their fellows helped them. Two had shared a fire with her, some nights ago, although she was careful not to eat their food, even though they offered.

It was a cruel spirit that would punish starving people for what they had been forced to eat, but the spirits had never pretended to be kind.

Her companions at the fire had warned her, though. “Be careful,” said one. “Be quick, quick, quiet. There’s a few to watch for. They were bad before and they’re worse now.”

“Bad,” said the second one. His breathing was very labored and he had to stop between each word. She could tell that it frustrated him, trying to speak between the pauses. “Not . . . right. All . . . of us . . . now”—he shook his head ruefully—“but them . . . angry.”

“It doesn’t do any good to be angry,” said the first one. “But they won’t listen. Ate too much. Got to like the taste.” She cracked a laugh, too high, looking down at her hands. “We stopped as soon as there was something else, but they kept eating it.”

The second one shook his head. “No,” he said. “More . . . than that. Always . . . angry. Born.”

“Some are born that way,” Marra agreed, nodding to him. She knew too well.

Some of those people are men. Some of those men are princes. Yes, I know. It is a different kind of anger. Something darker and more deliberate.

He looked relieved that she had understood. “Yes. Angrier . . . now. Much.”

All three of them sat in silence around the fire. She stretched her hands toward the flames and exhaled slowly.

“Mostly they kill us,” said the first one abruptly. “We can’t always run. Things get confused—” She sketched a gesture in the air above her eyes that Marra could not begin to understand, although her companion nodded when he saw it. “We’re easy to catch if it’s like that. But if they see you, they’ll try for you, too.”

The fire crackled. This land was very damp, and she was grateful for the heat, and yet—“Aren’t you worried that they’ll see the fire?”

The woman shook her head. “They hate it,” she said. “It’s the punishment. The more they eat, the more they fear it—they do not cook the flesh, you see . . .” She rubbed her face, obviously distressed.

“Safer,” said the man. “But . . . can’t burn . . . all the time.”

They leaned against one another. She bent her head down against his shoulder and he reached his arm across his body to hold her close.

A few days ago, Marra would have wondered why they did not leave this terrible land. She no longer did. They might not be sane, as the outside world understood it, but they were not fools. If they felt that they were safer here than they were outside it, it was not her place to tell them otherwise.

If I had to explain to everyone I met what had happened to me, have them judge me for what I’d had to do—no, I might think a land with a few roving cannibals was a small price to pay, myself. At least here, everyone understands what’s happened, and they are as kind to each other as they can be.

As a girl, she would not have understood that, but Marra was not the girl that she had been. She was thirty years old, and all that was left of that girl now were the bones.

For a moment she had envied them, two people punished through no fault of their own, because they had each other.

Now, as she sat in the pit of bones, the skeleton cradled against her chest twitched.

“Shhhh . . .” whispered Marra into the skull’s openings. “Shhhhh . . .”

Bone dog, stone dog . . . black dog, white dog . . .

She heard the footsteps as he approached. Had he seen her?

If he had, then he, too, dismissed it as a trick of the light. The footfalls skirted the edge of the pit, and the sound of breathing faded away.

“Probably harmless,” she murmured to the skull. Even if he were not, she would be a difficult target.

The other, gentler folk in here were uniquely vulnerable. If you had learned not to trust your own senses, you might wait too long to run from an enemy.

Marra was no longer as sure of her own perceptions as she had once been, but the edges of her mind were only slightly frayed, not blasted open by furious spirits.

When the footsteps had been gone for many minutes and the crows had settled, she sat up again. Fog lined the edges of the wood, hanging in low swirls over the meadow. The crows cawed together like a disjointed heartbeat. Nothing else moved.

She bent back over the bone dog again, fingers moving on the wires, hoping to finish her task before darkness fell.

* * *

The bone dog came alive at dusk. It was not quite completed, but it was close. She was bent over the left front paw when the skull’s jaws yawned open and it stretched as if waking from a long slumber.

“Hush,” she told it. “I’m nearly done—”

It sat up. Its mouth opened and the ghost of a wet tongue touched her face like fog.

She scratched the skull where the base of the ears would be. Her nails made a soft scraping sound on the pale surface.

The bone dog wagged its tail, its pelvis, and most of its spine with delight.

“Sit still,” she told it, picking up the front paw. “Sit, and let me finish.”

It sat politely. The hollow eye sockets gazed up at her. Her heart contracted painfully.

The love of a bone dog, she thought, bending her head down over the paw again. All that I am worth these days.

Then again, few humans were truly worth the love of a living dog. Some gifts you could never deserve.

She had to wrap each tiny foot bone in a single twist of wire and bind it to the others, then wrap the entire paw several times, to keep it stable. It should not have held together, and yet it did.

The cloak had gone together the same way. Nettle cords and tattered cloth should have fallen apart, and yet it was far more solid than it looked.

The dog’s claws were ridiculously large without flesh to cloak them. She wrapped each one as if it were an amulet and joined them to the basket of thin wires.

“Bone dog, stone dog,” she whispered. She could see the children in her head, three little girls, chanting to each other. Bone dog, stone dog . . . black dog, white dog . . . live dog, dead dog . . . yellow dog, run!

At run, the little girl in the middle of the rope had jumped out and begun to run back and forth through the swinging rope, the only sound her feet and the slap of the rope in the dust. When she finally tripped up, the two girls on the ends had dropped the rope and they had all begun giggling together.

The bone dog rested his muzzle on her forearm. He had neither ears nor eyebrows, and yet she could practically feel the look he was giving her, tragic and hopeful as dogs often were.

“There,” she said, finally. Her knife was dulled from cutting wire and it took her several tries to hack the last bit apart. She tucked the sharp end underneath the joint where it would not catch on anything. “There you are. I hope that’s enough.”

The bone dog put its paw down and tested it. It stood for a moment, then turned and sprinted into the fog.

Marra’s fist clenched against her stomach. No! It ran—I should have tied it. I should have thought it might run—

The clatter of its paws faded into the whiteness.

I suppose it had another master somewhere, before it died. Perhaps it’s gone to find them.

Her hands ached. Her heart ached. Poor foolish dog. Its first death had not been enough to teach it that not all masters were worthy.

Marra had learned that too late herself.

She looked into the pit of bones. Her fingers throbbed—not in the horrible stinging way they had when she pieced together the nettle cloak, but deeper, in time to her heartbeat. There was redness working its way up her hands. One long line was already snaking through her wrist.

She could not bear the thought of sitting down and sculpting another dog.

She dropped her head into her aching hands. Three tasks the dust-wife had given her. Sew a cloak of owlcloth and nettles, build a dog of cursed bones, and catch moonlight in a jar of clay. She’d failed on the second one, before she’d even had a chance to start the third.

Three tasks, and then the dust-wife would give her the tools to kill a prince.

“Typical,” she said into her hands. “Typical. Of course I’d manage the impossible thing, then not think that sometimes dogs run off.” For all she knew, the bone dog had caught the wisp of a scent and now it would end up a hundred miles away, chasing bone rabbits or bone foxes or bone deer.

She laughed into her swollen hands, misery twisting around, as it so often did, into weary humor. Well. Isn’t that just the way?

This is what I get for expecting bones to be loyal, just because I brought them back and wired them up. What does a dog know about resurrection?

“I should have brought it a bone,” she said, dropping her hands, and the crows in the trees took up the sound of her laughter.

Well.

If the dust-wife had failed her—or if she had failed the dust-wife—then she would make her own way. She’d had a godmother at her christening who had given her a single gift and smoothed her path not at all. Perhaps there was a debt owing there.

She turned and began to make her way, step by dragging step, out of the blistered land.

2

Marra had grown up sullen, the sort of child who is always standing in exactly the wrong place so that adults tell her to get out of the way. She was not slow, exactly, but she seemed younger than her age, and very little interested her for long.

She had two sisters, and she was the youngest. She loved her oldest sister, Damia, very much. Damia was six years older, which seemed a lifetime. She was tall and poised and very pale, a child of Marra’s father’s first wife.

The middle sister, Kania, was only two years older than Marra. They shared a mother but no goodwill.

“I hate you,” said twelve-year-old Kania, through gritted teeth, to ten-year-old Marra. “I hate you and I hope you die.”

Marra carried the knowledge that her sister hated her snugged up under her ribs. It did not touch her heart, but it seemed to fill her lungs, and sometimes when she tried to take a deep breath, it caught on her sister’s words and left her breathless.

She did not talk to anyone about it. There was no point. Her father was not unkind, but he was mostly absent, even if he was physically present. At best he would have patted her awkwardly on the back and sent her to the kitchen for a treat, as if she were very small. And her mother, the queen, would have said, “Don’t be absurd, your sister loves you,” in a distracted voice, opening the latest dispatch from her spymasters, making the political decisions to keep the kingdom from falling into ruin.

When Prince Vorling was betrothed to Damia, the household rejoiced. Marra’s family ruled a small city-state with the misfortune to house the only deep harbor along the coast of two rival kingdoms. Both those kingdoms wanted that harbor, and either one could have rolled over the city and taken it with hardly a moment’s effort. Marra’s mother had kept them balancing between two knives for a long time.

But now Prince Vorling, of the Northern Kingdom, would marry Damia and thus cement an alliance between them. If the Southern Kingdom tried to take the harbor, the Northern Kingdom would defend it. Damia’s first son would sit someday upon the Northern throne, and her second (if she had one) would rule the harbor city.

It was, perhaps, a trifle odd to expend a firstborn son on so small a thing as the Harbor Kingdom, but it was said that the royal family of the North had grown thin blooded and had married too many close cousins over the centuries. They were protected by powerful magic, but magic could not fix blood, so the kings looked to marry outside their borders. By sealing the Harbor Kingdom and its shipping port to them by marriage, the Northern Kingdom enriched their blood and their coffers at a single stroke.

“At last,” said Marra’s father. “At last, we will be safe.” Her mother nodded. Now the Southern Kingdom would not dare to attack them, and the Northern Kingdom would no longer need to.

It was only Marra who cried. “But I don’t want you to go!” she sobbed, clinging to Damia’s waist. “You’re going away!”

Damia laughed. “It will be all right,” she said. “I’ll come visit. Or you’ll come visit me.”

“But you won’t be here!”

“Stop it,” said her mother, thin lipped, pulling her daughter away from her stepdaughter. “Don’t be selfish, Marra.”

“Marra’s just bitter because she doesn’t have a prince,” said Kania, taunting.

The unfairness of this made Marra cry harder. She was twelve and she knew that she was too old to throw a tantrum, but she felt one coming on anyway.

The nurse was fetched to take her away, and that meant that Marra did not see Damia leave, with all the pomp and ceremony of a bride going to her bridegroom’s kingdom.

She was watching five months later, though, when Damia’s body was brought home in state.

There was a black wagon pulled by six black horses, flanked by riders dressed in mourning bands. There were three black carriages before and after the wagon, the curtains drawn. Their horses, too, were black. They had black bridles and black saddles and black barding.

It struck Marra, watching, as an extravagance of grief. Someone wanted the world to know how sad he could afford to be.

“A fall,” said the whispers. “The prince is heartbroken. They say she was carrying his child.”

Marra shook her head. It was not possible. The world could not be so poorly ordered that Damia could be allowed to die.

She did not cry, because she did not believe that Damia was dead.

It seemed very strange that everyone else did believe it. They ran back and forth, sometimes weeping, more often planning the details of the funeral.

Marra crept into the chapel that night. If she could prove that the body lying there was not Damia, then all the foolishness of funerals could be set aside.

The shrouded figure smelled strongly of camphor. There was a death mask atop the shroud. It was Damia, her face composed.

Marra stared at the figure for a little while and thought that it had been several days since they had heard of Damia’s death. They had been cool days, but not cold. The camphor could not quite chase out the scent of decay.

If she tried to push aside the death mask and tear off the shroud, she would see a rotting corpse. Who knew what it would look like?

I was thinking like a little child, she thought angrily. Thinking that I would be able to tell if it was Damia. It could be anyone under there at all.

Even her.

She crept away and left the shroud undisturbed.

The funeral was lavish but rushed. The riders that the prince had sent were better dressed than Marra’s mother and father. Marra resented her parents for being shabby and resented the prince for making it obvious.

They lowered the body into the ground. It could have been Damia. It could have been anyone. Marra’s father wept, and Marra’s mother stared straight ahead, her knuckles white where they gripped her cane.

Days followed, one after another, chasing each other into weeks. Marra came to believe that it had been Damia, mostly because everyone else seemed to believe it, but by then it seemed too late to mourn, and anyway, how could such a thing be possible?

She tried, once, to say something to Kania.

“Of course she’s dead,” said her sister shortly. “She’s been dead for months.”

“Has she?” asked Marra. “I mean—she has. But . . . dead! Really? Does it make any sense to you?”

Kania stared at her. “Don’t be ridiculous,” she said. “It doesn’t have to make sense. People just die, that’s all.”

“I guess,” said Marra. She sat down on the edge of the bed. “I mean . . . everybody says she is.”

“They wouldn’t lie about it,” said Kania. “Marrying the prince meant that we were going to be safe. If Damia’s dead, then the prince will marry someone else and we’ll be in danger again.”

Marra said nothing. She had not thought of that, either.

I must start to think like a grown-up. Kania is doing it better than I am.

The two years between them seemed suddenly vast, full of things that Marra knew but had never thought about.

Kania sighed. She reached over and hugged Marra with one arm. “I miss her, too,” she said.

Marra accepted the hug, though she knew her sister hated her. Hate, like love, was apparently complicated.

* * *

The edge of the blistered land was before her. Marra looked at it for nearly a minute, thinking.

It was strange how clear the edge was. It looked like the shadow cast by a cloud. This bit here was dark and that bit was bright. It took a moment or two for wind blowing from one side to reach the other.

She could hear the crows calling back and forth. The ones on the outside sounded like normal crows—Awk! Awk! Awk!

The ones over her head sounded like Gah-ha-hawk! Gah-ha-hawk!

She wondered if the outside crows hated the crows of the blistered land the way that the villagers outside hated the people inside. They had warned her against going inside.

“They’ll kill you soon as look at you,” one man had said, leaning against the fence. A second man—his friend or his brother, Marra wasn’t sure—nodded in time. “It’s creeping,” the second man said. “Gets a little bigger every year.”

The first one nodded. “There’s trees that used to be on this side that are on that side now.” He spat. “Full of cannibals. You go in there, they’ll eat you and lick out your bones.”

“Ain’t no reason to go in,” said the second one. “Not for canny folk.”

They looked at her suspiciously. The first one spat again, near her feet.

Marra had found that the people inside were much more welcoming. They had shared their fire and given her the best directions they could offer.

I was worried about the wrong things.

As usual.

It had taken her a day and a half to get to the blistered land from the dust-wife’s home. In the back of her head, Marra had a notion that it should have taken longer. She’d never heard of the blistered land before and it shouldn’t have just been there, right there, practically on the doorstep.

Magic, maybe. Magic or worse. That a land like this existed at all. That the gods had destroyed it. That if you picked a direction and walked, holding the thought in your mind, you would come to it, no matter which way you went.

She did not like the thought. It meant that the blistered land might touch her own kingdom, that the gods that would punish starving people might someday reach out and touch her own. It was too close and too real and too hungry.

Marra pulled the owlcloth cloak around her shoulders and stepped out of the blistered land.

The curse tugged at her as she went, an itch like mosquito bites across her skin. She slapped at her arms instinctively, even knowing that there was nothing there.

The ground felt strangely hard underfoot, as if she had just stepped off carpets and onto stone. She looked around, blinking in the bright light.

She made ten steps, more or less, holding her hands against her chest, before someone shouted, “Stop!”

* * *

It was barely a season after Damia’s funeral when word came down that the prince was willing to marry Kania.

“Not yet,” said Marra’s mother. “Not for a year or two. It wouldn’t be seemly. But after that, to keep the alliance going.”

Kania nodded. Her skin was darker than Damia’s had been and she was at least six inches shorter, but at that moment, Marra thought they looked very much alike—resolute and strong and a little bit afraid.

“No . . .” said Marra, but she said it quietly, and no one heard.

It was absurd to think that Kania would die because Damia had. Damia’s death had been an accident—that was all. It had been a tragedy. It was no one’s fault.

Marra knew all these things. They did not shake the gnawing dread that had lodged itself under her breastbone. She felt as if the dread must be visible to other people, like a growth, and it seemed strange that no one ever commented on it.

“Be careful,” she said to Kania one day. “Please. Don’t . . .”

She stopped. She didn’t know how to finish that. Don’t get married? Don’t walk down any stairs?

Kania gave her a sharp look. “Careful how?”

Marra shook her head miserably. “I don’t know,” she said. “I just feel like something’s going to go wrong.”

“Nothing will go wrong,” said Kania. “What happened to Damia was an accident. It won’t happen to me!”

Her voice rose sharply on the last word, and she turned and stalked away.

I’ve made a mess of it again. I can’t say anything until I know more.

A year passed, and Kania went away to the north, with slightly less pomp than Damia had. Marra dug her nails into her palms and watched her go. Her sister was much too young, and no one was saying anything about it.

Before Damia died, Marra would have spoken up and demanded answers and explanations. Now she bowed her head and said nothing.

Everyone else knows. They must know. They are not talking about it for a reason. Why is no one talking about it?

“Don’t cry,” her nurse said, as she stood on the castle wall, watching the prince’s horses take Kania away. “Try to be happy for her. You’ll have a prince of your own someday.”

Marra shook her head. “I don’t think I want one,” she said.

“Of course you do,” said her nurse. She was hired to see that the princesses were dressed and fed and learned to walk and talk and smile politely, not to unravel the strands of their thoughts. Marra knew this and knew that she was asking for too much, so she said nothing more and simply watched the horses take her sister farther and farther away.

* * *

Marra went to the convent eight months later. She was fifteen. It made no sense that she would go to a convent, when she might conceivably marry a prince and bear sons, but Prince Vorling did not want that. Kania had not yet had a child. If Marra married and bore a son before Kania did, then that child might be a challenge to the throne of the little Harbor Kingdom.

Prince Vorling got what he wanted. The Northern Kingdom’s knife was still at the little kingdom’s throat, and now he had Kania as a hostage.

The queen explained this to her, although she did not use the word hostage. She used words like expediency and diplomacy, but Marra knew very well that hostage was lurking somewhere in the background. Kania was hostage to the prince. Marra’s future children, if any, were hostage to Kania’s fertility.

“You’ll like the convent,” said the queen. “More than you like it here, at any rate.” She and Marra looked very much alike, round and broad-faced, indistinguishable from any number of peasants working the fields outside the castle. The queen’s mind was as brittle-sharp as an iron dagger, and she spent her days delicately threading the web of alliances and trade agreements that allowed their kingdom to exist without being swallowed up. She had apparently decided that Marra could be withdrawn from the game of merchants and princes and safely set aside. Marra both resented her mother for being so clear-eyed and was grateful to be free of the game, and she added this to the store of complicated things piled up beneath her heart.

And she did like the convent. The house of Our Lady of Grackles was quiet and dull, and the things that people expected of her were clear-cut and not shrouded behind diplomatic words. She was not exactly a novice, but she worked in the garden with them and knit bandages and shrouds. She liked knitting and cloth and fibers. Her hands could work and she could think anything she wanted and no one asked to know what it was. If she said something foolish, it reflected only on her, and not on the entire royal family. When she shut the door to her room, it stayed shut. In the royal palace, the doors were always opening, servants coming and going, nurses coming and going, ladies-in-waiting coming and going. Princesses were public property.

She had not realized that a nun had more power than a princess, that she could close a door.

No one but the abbess knew that she was a princess, but everyone knew that she somehow was of noble rank, so they did not expect her to shovel the stable where the goats and the donkey lived. When Marra realized this, a few months after she had arrived, something like anger flared up inside her. She had been proud of the work she was doing. It was something that belonged to her, to Marra, not to the princess of the realm, and she did it well. Her stitches were small and fine and exact, her weaving uniform and careful. That she was still living under the shadow of the princess woke the stubbornness in her. She went to the stables and picked up a pitchfork and set, inexpertly, to work.

She was very bad at it, but she did not stop, and the next day she went back to it, even though her back ached and blisters formed on her palms. It is no worse than when you first fell off a horse. Keep shoveling.

The goats watched her suspiciously, but that did not mean anything, because goats watched everyone suspiciously. She suspected that they didn’t think much of her shoveling technique.

“No one expects you to do this,” said the mistress of novices, standing in the doorway of the stable. Her shadow fell down the central aisle of the stable, like a standing stone.

“They should,” said Marra, gripping the pitchfork’s handle while her blisters shrieked. She edged the tip of the tines under a clot of manure and lifted it cautiously.

The mistress sighed. “Sometimes we get novices who have never worked,” she said, almost absently. “Some of them fear hard work. Then you get some who do not feel work should apply to them. And then again, some who wallow in it, who treat it like mortification of the flesh.”

Marra flipped the manure into the waiting wheelbarrow and straightened up. Her back asked if she really, truly wanted to be doing this. “Which do you think I am?”

The mistress shrugged. “Eventually, everyone winds up in the same place. You do the work because it needs to be done, and it is satisfying to have it done for a little while.” She took the pitchfork away and cleared a bit of stall with two or three expert strokes. “Hold it like this. You are holding too close to the fork, you lose the leverage.”

Marra took the pitchfork back and tried, cautiously. It was easier that way and seemed to weigh less. The goats, less amused now that she was doing it correctly, wandered off.

“I will add you to the rota,” said the mistress of novices, flicking a bit of dirt from her robe. “When you have finished this stall, be done for the day. And speak to the Sister Apothecary about those blisters.”

“Thank you,” said Marra, almost inaudibly, and bowed her head. She felt as if she had passed some test, even if it was only in her mind, and she did not know what, if anything, she had learned.

3

On the edge of the blistered land, Marra stood and looked around for the source of the voice. It was too bright here. She had gotten used to the dimness of the blistered land. Her eyes ached as if she were staring at a snowfield instead of a dusty road and a line of fences.

“I saw you,” said the voice. She squinted against the light and saw the speaker. A man. Perfectly ordinary looking, in the gray-brown garb that everyone wore, here on the edge of the desert. There was nothing that stood out about him, except that he was shouting at her.

“Hello?” she croaked. Her voice sounded as harsh as the crows overhead.

“I saw you come out of there,” growled the man. “You’re one of them. One of the bad ones.”

Marra shook her head. This was absurd. She’d broken bread with cursed souls, and of course it was a supposedly sane man who was going to try to stop her. It was ridiculous. It was . . .

Typical. The prince is sane, too, as men judge these things. I should probably have seen it coming.

“I’m not from there,” she said, fighting the urge to defend the people inside. “I got lost. I’m from the Harbor Kingdom.”

“The Harbor Kingdom is nowhere near here.”

Despite herself, Marra felt a pang of relief. Good. The blistered land did not touch her own kingdom—not yet.

Her relief was short-lived. The man was carrying a shovel. Marra eyed it warily. Shovels were good for burying dead bodies, and also for making bodies dead in the first place.

“I traveled for a long time,” said Marra. “To get here. Well, not here specifically. To the dust-wife.” She wondered if the dust-wife’s name would help. Surely everyone respected dust-wives?

The man spat on the ground. “Trying to raise the dead?” he asked. “The bad dead in there?” He took a step forward.

“No, I . . .” Marra retreated, darting a glance over her shoulder. Could she make it to the safety of the fog?

This is completely ridiculous. Did the hero Mordecai have to stop and explain about the poison worm to the locals? Did they try to chase him back into the swamps? Bad enough that Marra had failed in the task, but now this?

He took another step forward and lifted his shovel. “You go back in,” he said. “You go back in or I’ll kill you. You stay where you belong.”

“But—”

She tried to explain. She really did. The words spilled out of her like blood from a wound, a jumble of explanations about the dust-wife and the bone dog and three impossible tasks and traveling on the coaches from the Harbor Kingdom, and after about thirty seconds, she realized that he wasn’t listening to her at all. He was staring past her, into the fog.

Marra turned and saw shadows moving in the murky edge of the blistered land.

“Oh god,” the man whispered, clutching his shovel. “Something’s coming.”

Marra froze, trapped between the shadow and the shovel, not daring to move. She could hear footsteps pounding on the earth, a rattling sound, and then . . .

It galloped out of the fog, an articulated ghost, bouncing on its forelegs. Briefly it rose up and swiped at her face with its nonexistent tongue, then dropped back down again.

“Dog,” she said. Tears began to spill down her face. “Dog. You came back.”

The bone dog gazed up at her from empty sockets, mouth open in a fleshless grin.

“M-monster!” shouted the farmer, scrambling backward. “Monster!”

Monster? Where?

Marra looked behind her, wondering if something terrible had come out of the blistered land. The skeleton dog barked soundlessly, bouncing on his paws, and Marra heard the rattle-bone click of vertebrae and wire.

She grabbed the dog by the backbone, trying to find a convenient way to hold him. You couldn’t very well scruff an animal with no scruff. “Hush!” she begged him. “Settle down! Be quiet!”

The edge of the blistered land was calm. A crow cawed and it echoed in a space neither here nor there. The man was long gone and had left his shovel behind.

Monster?

And then she looked down and realized that her assailant had been talking about the skeleton of the dog.

Oh. Right. I suppose . . . yes.

She scowled. He was a good dog. He had excellent bones and even if she had used too much wire and gotten it a bit muddled around the toes and one of the bones of the tail, she’d think that a decent person would stop and admire the craftsmanship before they screamed and ran away.

“No accounting for taste,” she muttered. She was still crying a little, but her tears felt as ghostly as the bone dog’s tongue. “All right. Let’s go back to the dust-wife and show her you exist.”

* * *

Because she was a novice but would never take orders as a nun, Marra was not expected to attend services three times a day. Sometimes she did anyway. The services for Our Lady of Grackles were short. The goddess—or saint, no one was quite sure—did not care for complex theology. No one knew what she wanted, only that she was generally kindly disposed toward humans. “We’re a mystery religion,” said the abbess, when she’d had a bit more wine than usual, “for people who have too much work to do to bother with mysteries. So we simply get along as best we can. Occasionally someone has a vision, but she doesn’t seem to want anything much, and so we try to return the favor.”

The statue of Our Lady of Grackles was a woman with a hood that fell in folds over her face to the lips. She had a small, wry smile, and four birds perched on her arms. Her altar cloths were embroidered with depictions of lesser saints. Since the goddess did not seem to want anything, the nuns offered prayers to saints that had no worshippers of their own. “Some of them probably aren’t alive,” said the abbess, lighting candles, “but a few prayers for the dead won’t go amiss, either.”

The convent shared a wall with a monastery, and if she had a chaperone, Marra could go to their library. She had never been terribly easy with reading, but there were books on everything, not merely religion, and she found books on weaving and knitting. It was worth puzzling out the longest words to learn new patterns. She pieced bits together on scraps and sometimes things worked and sometimes they didn’t, but the burn of curiosity to see if the next thing would work, and the next thing, and the next, kept her forging ahead.

She could not remember ever feeling such a thing before. There was no call to nurture intellectual curiosity among princesses. She did not even quite know what to call it. It felt like a light shining in her chest and she could see just a little way ahead, and that was enough to keep her going forward. There was no one to tell her what she wanted to know or whether the information even existed. She had no one to share her excitement with, but she did not mind, because it did not occur to her that anyone else might care.

Because she was royal, and not quite a nun, Marra was allowed to keep going forward. When, once a season, the abbess wrote to the royal house and requested the payment to keep a princess, she mentioned that her charge was very fond of knitting and embroidery, and so fine wool and dyed thread found its way to the convent alongside the coin.

Her mother, the queen, sent careful, precise letters once a month. There was nothing in them that a spy could have found interesting. The king had a cold. The apple trees in the courtyard were flowering. The queen missed her. (Marra did not know whether or not she believed this bit.) And one line, the same every month, “Your sister says that she is well.”

When she was eighteen, Marra fell passionately in love with a young acolyte from the monastery who was apprenticed to the Brother Cellarer. He had beautiful eyes and skilled hands and she was utterly lost. They had four or five frantic, awkward couplings, and then Marra overheard him boasting to the other acolytes that he had bedded one of the king’s by-blows. It did not matter that they jeered at him and didn’t believe him. She went to her room and curled into a ball of misery and decided that she would die of a broken heart. Minstrels would write sad songs about how she had turned her face to the wall and died of the false-heartedness of men.

She could not quite make up her mind whether she wanted to be a ghost who would haunt the convent or not. It would be very satisfying to be a sad-eyed, beautiful ghost who drifted through the halls, gazing up at the moon and weeping silently, as a warning to other young women. On the other hand, she was still short and round-faced and sturdy, and there were very few ghost stories about short, sturdy women. Marra had not managed to be pale and willowy and consumptive at any point in eighteen years of life and did not think she could achieve it before she died. Possibly it would be better to just have songs made about her.

The Sister Apothecary came to her, the nun who doctored all the residents of the convent for various ailments, and who compounded medicines and salves and treatments for the farmer’s wives who lived nearby. She studied Marra intensely for a few minutes. “It’s a man, is it?” she said finally.

Marra grunted. It had occurred to her about an hour earlier that she did not know how the minstrels would find out that she existed in order to write the sad songs in the first place, and her mind was somewhat occupied with this problem. Did you write them letters?

The Sister Apothecary poured out two small measures of cordial and handed Marra one. “Drink with me,” she said, “and I’ll tell you about the first boy I ever loved.”

It took three more measures of cordial and two more tales of woe, but Marra uncurled and told the Sister Apothecary everything. The Sister gave her a tea to bring her courses on, just in case, and went to the abbess, and the young man was reassigned to another monastery a week later. Marra was left feeling raw and hollow, and brooding over the fact that somehow “unknown noblewoman” had translated into “king’s bastard daughter” in the minds of the monks.