Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Atlantic Books

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

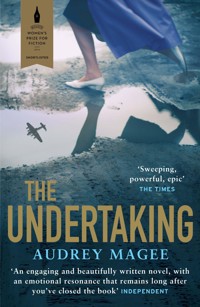

The debut novel by the author of The Colony, longlisted for the 2022 Booker Prize A soldier on the Russian Front marries a photograph of a woman he has never met. Hundreds of miles away in Berlin, the woman marries a photograph of the soldier. It is a contract of business rather than love. When the newlywed strangers finally meet, however, passion blossoms and they begin to imagine a life together under the bright promise of Nazi Germany. But as the tide of war turns and Allied enemies come ever closer, the couple find themselves facing the terrible consequences of being ordinary people stained with their small share of an extraordinary guilt...

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 338

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2014

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

The Undertaking

First published in Great Britain in 2014 by Atlantic Books, an imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd.

Copyright © Audrey Magee, 2014

The moral right of Audrey Magee to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination and not to be construed as real. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities, is entirely coincidental.

9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

A CIP catalogue record is available from the British Library

Hardback ISBN: 978 1 78239 102 9Trade paperback ISBN: 978 1 78239 103 6E-book ISBN: 978 1 78239 104 3

Printed in Great Britain

Atlantic BooksAn imprint of Atlantic Books LtdOrmond House26–27 Boswell StreetLondon WC1N 3JZ

www.atlantic-books.co.uk

For Johnny

Contents

The Undertaking

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Chapter 31

Chapter 32

Chapter 33

Chapter 34

Chapter 35

Chapter 36

Chapter 37

Chapter 38

Chapter 39

Chapter 40

Chapter 41

Chapter 42

Chapter 43

Chapter 44

Chapter 45

Chapter 46

Chapter 47

Chapter 48

Chapter 49

Chapter 50

Chapter 51

Chapter 52

Chapter 53

Chapter 54

Chapter 55

Chapter 56

Chapter 57

Chapter 58

Chapter 59

Chapter 60

Acknowledgements

Note on the Author

The Undertaking

1

He dragged barbed wire away from the post, clearing a space on the parched earth, and took the photograph from the pocket of his tunic. He pressed the picture against the post and held it in place with string, covering the woman’s hair and neck, but not her face. He could still see that, still see her sullen eyes and sulking lips. He tied a knot, and spat at the ground. She would have to do.

He lay down to soak up the last of the summer sun, indifferent to the swirling dust and grit, wanting only to rest, to experience the momentary nothingness of waiting. But he sat up again. The ground was too hard, the sun too hot. He lit a cigarette and stared into the shimmering heat until he located a rotund figure, its arms and legs working furiously, but generating little speed. The man arrived eventually, grumbling and panting, sweat dribbling onto the white of his clerical collar.

‘Why are you so bloody far away?’ he said.

‘I wanted privacy.’

‘Well, you’ve got that. Is everything ready?’

‘Yes.’

‘Let’s get on with it, then,’ said the chaplain. ‘We should make it just in time.’

He drew a pencil and piece of crumpled paper from his pocket.

‘Who is the groom, Private?’

‘I am.’

‘And your name?’

‘Peter Faber.’

‘And the witnesses?’ said the chaplain.

‘Over there,’ said Faber, pointing at three men curled up in sleep.

The chaplain walked over and kicked at them.

‘They’re drunk.’

Faber blew rings of smoke at the blue sky.

‘Are you drunk too, Faber?’

‘Not yet.’

The chaplain kicked harder. The men moved, grudgingly.

‘Right, we’re doing this now. Put your cigarette out, Faber. Stand up. Show a little respect.’

Faber stubbed the cigarette into the soil, pressed his long, narrow hands against the earth and slowly got to his feet.

‘Hair out of your eyes, man,’ said the chaplain. ‘Who is it you’re marrying?’

‘Katharina Spinell.’

‘Is that her there? In the photograph?’

‘As far as I know.’

‘As far as you know?’

‘I’ve never met her.’

‘But you want to marry her?’

‘Yes, Sir.’

‘You’re keen.’

‘To escape this stinking hellhole.’

The priest wrote briefly, and returned the pen and paper to his pocket.

‘We can begin,’ he said. ‘Your helmet, Faber?’

‘That’s it. On the ground. Next to the photograph.’

‘Gather round, men,’ said the priest. ‘Right hands on the helmet.’

They squatted in a small circle around the dirty, dented helmet, knees and elbows tumbling into each other.

‘Groom first.’

Faber placed his hand on the metal, but quickly took it off again.

‘It’s too bloody hot.’

‘Get on with it,’ said the chaplain. ‘It’s a minute to twelve at home.’

Faber pulled his sleeve over his hand.

‘The flesh of your hand, Faber. Not the sleeve.’

The priest picked up a fistful of earth and scattered it over the helmet.

‘There.’

‘Thank you.’

Faber replaced his hand, and the other men followed. The chaplain spoke, and within minutes Faber was married to a woman in Berlin he had never met. A thousand miles away, at exactly the same moment, she took part in a similar ceremony witnessed by her father and mother; her part in a war pact that ensured honeymoon leave for him and a widow’s pension for her in the event of his death.

‘That’s it,’ said the chaplain. ‘You’re now a married man.’

Each of the men shook his hand.

‘I need a drink,’ said Faber.

He picked up his helmet, but left the photograph and walked back to camp.

2

He stared, for longer than was polite, and then spoke.

‘I’m Peter Faber.’

‘I know. I recognize you from your photograph.’

‘You’re Katharina?’

She nodded and he shook her hand, surprised by the softness of her flesh, by the tumble of dark hair over her shoulders. She tugged at him.

‘My hand,’ she said. ‘May I have it back?’

‘I’m sorry.’

He dropped it and stepped back onto the pavement, to stand beside his pack and gun. She stayed where she was, her hip leaning into the half-opened door.

‘Was it a long journey, Mr Faber?’

‘Yes. Yes, it was. Very.’

She raised her hand against the sun and stared at him.

‘How long are you staying?’

‘Ten days.’

She pulled back the door.

‘You should come in.’

He picked up his kit and stepped into the dark, windowless hall. She put her hand over her nose and mouth. He stank. She moved away from him and set off up the stairs.

‘We’re on the second floor.’

‘Who’s we?’

‘My parents.’

‘I didn’t know you lived with them.’

‘I’m not paid enough to live by myself.’

‘I suppose not. What do you do?’

‘I told you in my letter. I work in a bank. As a typist.’

‘Oh yes, I forgot.’

He followed her up the frayed linoleum steps, watching each plump buttock as it shifted her skirt from side to side. She looked back at him.

‘Do you need any help?’

‘I’m fine,’ he said.

‘They’re looking forward to meeting you.’

She pushed open the door to the apartment. He slid the pack off his shoulder.

‘Let me take it,’ she said.

‘It’s too heavy.’

‘I’ll manage.’

She dragged the bag to a room behind the door, and returned for his rifle.

‘I’ll hang on to that,’ he said.

‘You’re in Berlin now.’

‘I prefer having it with me.’

He followed her along a narrow corridor to a small kitchen shimmering with condensation. Her parents got to their feet and saluted, each movement brisk with enthusiasm.

‘I’m Günther Spinell,’ said the man. ‘Katharina’s father.’

Faber shook his hand.

‘We are extremely proud to have a second soldier in our family.’

Faber looked down at the table. Four places were set, the crockery mismatched and chipped.

‘My son is to the north of you, Mr Faber. Somewhere outside Moscow.’

‘The poor sod.’

‘Johannes is a very brave man, Mr Faber.’

Katharina’s mother, her greying hair tightly curled, pointed to a chair.

‘Do sit down, Mr Faber.’

He unhooked his helmet, ammunition pouches and bread bag from his belts, and heaped them on a narrow counter beside the cooker. He sat down and scratched his back against the wood.

‘Are you comfortable?’

‘I’m fine.’

‘Did you have a good journey?’ said Mrs Spinell.

‘Nights in the train were cold.’

‘You don’t have a winter coat? No gloves?’

‘Not yet.’

‘Do you think Johannes has any?’

‘I don’t know.’

Mrs Spinell took a handkerchief from her sleeve and held it over her mouth and nose. She coughed, and cleared her throat.

‘Open the window, Katharina.’

He watched her push at the glass and lean out, her bottom sticking back into the room. She remained there, breathing the cold October air. He stared at her broad, fleshy hips.

‘Mr Ewald is stacking his crates,’ she said.

Faber heard wood slapping against wood.

‘That’s our grocer, Mr Faber,’ said her father. ‘A remarkably loyal man.’

‘He’s finishing early,’ said Mrs Spinell.

‘There wasn’t much today,’ said Katharina.

She turned back into the room.

‘Come on, Mother. We should make coffee.’

Faber lit a cigarette. Mrs Spinell placed an ashtray on the table. It was shaped as a swastika.

‘It belongs to Johannes, Mr Faber, but you can use it.’

The two women, without talking, set to work.

‘Have you been to Berlin before, Mr Faber?’ asked Mr Spinell.

‘No.’

‘Katharina will show you the city later.’

Mrs Spinell poured coffee and Katharina slid a slice of cake onto his plate.

‘It’s lemon.’

‘Thank you.’

He lifted the coffee to his nose, put it down and took up the cake. He let out a little sigh. They laughed.

‘I’m sorry,’ he said. ‘It’s been a long time.’

‘Go ahead,’ said Mrs Spinell. ‘Eat.’

He slipped the sponge into his mouth and chased it with the coffee, a rush of sweet and bitter. He did it again. They laughed again.

‘It’s so good, Mrs Spinell.’

‘It’s real coffee,’ said Mr Spinell. ‘From Dr Weinart, a friend of mine.’

‘And a neighbour gave us the eggs for the cake,’ said Mrs Spinell. ‘As a wedding present.’

‘She’s a communist,’ said Mr Spinell.

‘Mrs Sachs is a good person, Günther.’

‘That’s how they disguise themselves, Esther. That neighbourly sharing.’

Katharina sipped at her coffee, but nudged her cake towards Faber.

‘You have it. You want it more than I do.’

He ate her cake and a third slice, then sat back into his chair and lit another cigarette.

‘What do you teach, Mr Faber?’

‘Elementary, Mrs Spinell.’

‘Do you have a job?’

‘Yes. At the school I attended as a boy.’

‘Are they keeping it for you?’

‘Yes.’

‘But a teacher’s salary is not much,’ said Mrs Spinell. ‘Can you provide properly for my daughter?’

He felt their eyes on him. And then her father sniggered.

‘Katharina’s mother worries a lot,’ he said.

‘I am only trying to protect our daughter, Günther,’ she said. ‘To save her from what I had to go through at the end of the last war.’

‘Not now, Esther,’ said Mr Spinell.

‘Yes now. I had to scavenge for food, Mr Faber, rummage through bins to stop my children crying from hunger. Johannes howled and howled. He’s still hungry, I’m sure of it.’

‘Johannes is fine, Mother.’

‘You don’t understand, Katharina. And won’t until it’s your children suffering at the end of this war.’

‘It’ll be different this time, Esther,’ said Mr Spinell. ‘Everyone is afraid of us now. Victory will be swift.’

‘But he’ll still only be a teacher,’ said Mrs Spinell.

The sweating walls, hard chair and chipped crockery suddenly irritated Faber. He sat forward.

‘My father has been a teacher all his life, and has provided perfectly well for us,’ he said.

‘But will that be enough?’

‘It has been enough for my mother.’

‘Is she a modest woman?’

‘She is like any other woman, Mrs Spinell, who has dedicated her life to her husband and children.’

‘You can expect the same of Katharina,’ said Mr Spinell. ‘She will make a fine wife. And a fine mother.’

‘To be that she needs a husband with a good job, Günther.’

‘Teaching in our new world will be a very respected profession, Esther. Now, young man, tell us about the front. About Kiev.’

Faber lit a third cigarette, dragging the smoke deep into his lungs, silently absorbing its kick before slowly, evenly, releasing it into the room. He flicked the ash and cleared his throat.

‘The Russians are tenacious, Mr Spinell, but useless against our modern weaponry.’

‘It will all be ours by Christmas,’ said Mr Spinell. ‘Only three hundred kilometres from Moscow – we are invincible.’

‘We are doing well.’

‘I am very proud of you, and of all German soldiers,’ said Mr Spinell.

Faber inhaled again and nodded his head as he blew smoke towards the ceiling.

‘Thank you, Mr Spinell.’

‘When this war is over, we will have enough space, food, water and oil to last for centuries. You and my daughter can take all the land you need.’

‘Will we do that?’ said Katharina.

‘What?’

‘Take land? Move to the east and set up home there?’

He stared at her. He was sweating, even though the weather was cool.

‘Russia is poor, filthy and full of peasants living in houses made of mud. I’m here because I can’t stand the place.’

‘They will work for you,’ said Mr Spinell. ‘You can tear down their huts, clean up the landscape and build a beautiful German house. Imagine, your own farm.’

‘I know nothing about farming.’

‘There will be training. After the war, young men will be taught how to become farmers, how to grow food for Germany.’

‘I am happy to serve my country, but once the war is over I will return to Darmstadt to resume my life as a teacher.’

‘You could do other things. Earn more money.’

‘I like being a teacher.’

‘You seem such a capable man.’

‘I am a capable teacher.’

‘But there are so many other things to do, especially in Berlin. You can always teach when you are older, after you have made your money.’

Faber ground his cigarette into the ashtray and looked slowly around the room.

‘As you have done, Mr Spinell.’

Katharina began to clear the dishes.

‘Let me show you the city,’ she said. ‘Before it’s too dark.’

‘My fortunes are about to change, Mr Faber. And yours could too.’

‘I am happy with my life, Mr Spinell.’

‘Let me introduce you to Dr Weinart. He is a man of great integrity and connections.’

Faber stood.

‘I’ll think about it.’

He picked up his rifle.

‘You should leave that here,’ said Katharina.

‘I prefer to have it with me.’

‘It’s better left at home. We’re going to the park.’

‘I’ll take it with me.’

He moved towards the door.

‘You could at least wait for me,’ she said. ‘I have to get my coat.’

He left without her, going down the stairs and onto the street where the grocer was dismantling the stall at the front of his shop. The two men nodded at each other. Faber bounced up and down on his toes and rubbed at the sleeves of his tunic, buffeting his arms against the chilling wind. Katharina arrived on the doorstep, buttoning a coat too short for her skirt.

‘Should I go back to fetch you my brother’s coat?’

‘I’ll be fine.’

‘You look cold.’

‘I said I’d be fine.’

She walked past him, away into a city he did not know.

‘Where are we going, Katharina?’

‘To the park. The lake.’

‘You could at least wait for me.’

‘Why? You didn’t bother waiting for me.’

He stopped, a slight curve in his shoulders.

‘I’m sorry. I just needed to get away.’

‘My parents have that effect.’

‘It was intense. More than I had expected.’

‘It always is.’

‘How do you manage?’

‘Years of practice. They mean well. And they like you.’

‘Your mother hates me.’

‘She doesn’t. She just wants the best for me.’

‘And I’m not good enough?’

‘I’m her only daughter.’

‘And she thought you could do better than a teacher.’

‘Something like that.’

‘What was she hoping for? A doctor? A lawyer? They don’t marry bank clerks.’

‘I don’t suppose they do, Mr Faber.’

She walked ahead of him again. He caught up with her.

‘I’m sorry, Katharina.’

‘The bureau gave us details about you and four other men, including a doctor’s fat son.’

‘And your mother wanted him?’

‘Exactly.’

Faber laughed.

‘And instead she got a useless lanky schoolteacher.’

‘So it seems.’

‘So, where is he? The doctor’s fat son. Is he here? In Berlin?’

‘No. On the Russian front somewhere.’

‘He’s not fat any more then.’

They both laughed, and he offered her his arm. She took it.

‘And your father? What does he think?’

‘He approved of you. From the beginning.’

‘So why does he want to turn me into a farmer?’

‘He gets ideas. But you should see Weinart. It can’t do any harm.’

‘I said I’d think about it.’

She tugged his arm and he shortened his stride to keep pace with her. He took a deep breath and rolled from the heel to the toe of each foot, relishing the hard pavement, the distance from Russia. He felt her press into him.

‘Actually, my father likes you.’

‘How can you possibly tell?’

‘You’re a soldier, fighting on the front. That is enough for him.’

‘He made that clear, I suppose. And you? What do you think?’

‘I haven’t decided yet.’

‘Should I try to persuade you?’

‘You could try.’

He put his hands on her shoulders and steered her backwards, into the doorway of a shop that was already closed. He kissed her. She pushed him away and moved back onto the pavement, her right hand over her mouth, overwhelmed by his stench.

‘Your buckles were sticking into me,’ she said.

He smiled at her.

‘You’re a funny woman. Come on. Let’s see this park.’

She took his arm again. They walked through the gates to a bench overlooking a lake. Three boys were using the last of the day’s light to push boats around the lake with long sticks.

‘It’s good to sit among trees again. Russia’s forests are huge and dark. Frightening. I hate them.’

‘Is there anything you like about Russia?’

‘I was in Belgium before and it was civilized, comfortable. The people were like us. But Russia is different. Hard and hostile.’

‘It’ll soon be over.’

‘It’s such a big country. It seems to go on for ever.’

‘All the better for us.’

‘I suppose so.’

He kissed her again and she let him, briefly.

‘I thought it was against the rules for soldiers to kiss in public,’ she said.

‘I’m sure they’d forgive a man on his honeymoon.’

He stared at the lake, at the water lapping at the boys’ feet. She put her head on his shoulder, her face away from him.

‘Why did you marry?’ she said.

‘I wanted leave. And you?’

‘My mother said it would be a good idea. A bit of security, I suppose. The title of wife. Other girls are doing it.’

‘Why did you choose me?’

She smiled.

‘I don’t know. I liked your picture. Your hands, especially.’

He flipped them over and back.

‘What is there to like about my hands?’

‘I don’t know,’ she said.

She touched his thumb.

‘They’re strong. Sinewy. I like that.’

‘Ah yes, I remember. You don’t like fat.’

They both laughed and he kissed her again.

‘You’re prettier than I thought. Your hair and eyes. Your smile. Why didn’t you smile in the photograph?’

‘Mother said I shouldn’t. That it might put men off.’

‘You’ll have to stop listening to your mother.’

‘If I had, you wouldn’t be here.’

He opened her coat and ran his hands over her breasts.

‘You’re much prettier than I expected.’

‘So you keep saying. What had you expected?’

‘Somebody duller.’

‘Why would you marry somebody dull?’

‘God knows.’

They laughed and she stood up.

‘We should go,’ she said.

They passed the boys’ abandoned sticks.

‘What do your parents think of our marriage?’ she said.

‘I haven’t told them yet.’

‘Will they approve?’

‘I doubt it. They don’t know you.’

‘Nor do you.’

‘No, but I will.’

‘Will you, Mr Faber? You sound very sure of yourself.’

She took his arm.

‘We should hurry. Mother will be waiting for you.’

Mrs Spinell stood at the end of the corridor waving her arm, directing Faber to the bathroom. The bath was already full.

‘Please use the toothpaste and soap sparingly,’ she said. ‘They’re hard to come by.’

‘I will.’

‘Leave your clothes in there.’

‘Thank you.’

He smiled at Katharina, closed the door and began to undress, dried Russian soil falling to the floor as he removed layer after layer of clothing stiff with sweat. He looked in the mirror, at his tanned face and torso, at his white legs and red feet, blistered and chafed by months of marching over hard Russian earth.

He stepped into the hot water and submerged his head, wallowing in the warmth and quietness, in his distance from the other soldiers. He splashed water over his chest, relieved to be away from the noise, the chaos, the explosions, the buzzing of flies, the rattle of machine guns, from the voice of Katharina’s father making plans for the rest of his life. He didn’t need another father. Another set of parents.

He bent his knees and dropped his head under the water again. Away from the maggots crawling from corpses, from the sickly sweet stench of death. Cocooned in water. In stillness. In nothingness. He wanted to stay, but came up for air, took the flannel and soap from the end of the bath, and scrubbed himself until the water turned brown.

Mrs Spinell had left clothes, a razor, toothbrush and paste on a stool by the sink. He dragged the dull blade through his stubble and scrubbed at his teeth, so neglected that the foam turned from light pink to red. The trousers were too short, but the shirt fit well enough. He hesitated at the sweater with swastikas on each sleeve but pulled it on anyway, grateful for the warmth of the thickly knitted wool.

Mrs Spinell hurried from the kitchen as he opened the bathroom door.

‘It feels good to be clean again,’ he said.

He saw her looking at the floor.

‘Could you at least empty the bath?’ she said.

‘Of course.’

‘Your food is ready.’

‘I’m afraid that I used all the soap.’

‘And the toothpaste?’

‘There was only a small amount anyway.’

Katharina and Mr Spinell were already at the table. A single black pot sat between them, steam seeping from an ill-fitting lid.

‘Sit down,’ said Mr Spinell. ‘Eat with us.’

Mrs Spinell piled stewed vegetables onto her husband’s plate and selected three pieces of meat to place on top of the mound. She gave the same to Faber, but only two to herself and Katharina. Faber ate in silence, chewing at the gristly beef offcuts, mopping the watery sauce with grey bread. He sat back from his meal, months of hunger still to be sated.

3

Mrs Spinell slipped a brown paper bag into the pocket of her daughter’s faded blue apron.

‘You’ll need that.’

‘What is it?’

‘Powder.’

‘For what?’

‘He has lice.’

‘What? How can you tell?’

Katharina turned from the sink to look at Faber, who sat beside her father scrutinizing Johannes’ trophies and badges. He scratched his scalp, briefly but aggressively, still holding the thread of conversation. She whispered to her mother.

‘He doesn’t even know he’s doing it.’

‘The bath must have roused them,’ said Mrs Spinell. ‘That’s some husband you chose.’

Katharina wiped down the sink, although it was already clean.

‘You’ll have to treat him, Katharina.’

‘But I hardly know him.’

‘You’re his wife, Katharina. Do it or you’ll get them too. We all will.’

‘It’s too disgusting.’

‘They might be all over him. You’ll have to ask.’

Katharina folded the tea towel and took down the crockery required for breakfast.

‘Leave that, Katharina. You have to do this.’

‘I don’t want to do it. Any of it.’

‘It’s too late for that now, Katharina.’

Katharina rubbed her hands down the length of her apron and lingered as she hung it from its hook.

‘We should sort out your things, Peter.’

‘Your brother has done very well, Katharina.’

‘He was a star of the youth movement. He won everything.’

‘And you?’

‘I won nothing. I either tripped or came last.’

He smiled at her and followed her to the large bedroom used by her parents until that morning. Katharina had removed their possessions and cleaned the room, the walls, floor and bed, turning the space into her own, marking it with vases of rose buds on either side of the bed. She opened the door and inhaled sharply.

‘God, this place stinks,’ she said.

‘It’s my pack,’ said Faber. ‘I’m sorry.’

The lights still out, she opened the two large windows and looked down onto the street, drained of movement and light by the curfew.

‘My mother thinks you have lice.’

‘She’s probably right. Everybody does.’

‘How can you come here with lice in your hair?’

‘I didn’t know I had them. It’s second nature to scratch in Russia. Have you ever had them?’

‘We are sometimes a little hungry in Berlin, but never dirty.’

‘I didn’t mean it like that.’

Katharina looked at him. At the man she had chosen.

‘We need to sort you out,’ she said. ‘Close the shutters and curtains, but leave the windows open. Then we can turn on the light.’

Faber sat on the chair she had positioned below the bulb hanging from the ceiling. She lifted a clump of hair. Dozens of parasites were crawling across his scalp.

‘It’s disgusting.’

‘Will you ever kiss me again?’

‘I haven’t yet.’

She stepped back from him and sprinkled the powder over his head, its caustic cloud falling onto his face, into his eyes. She ignored his complaints.

‘Do you have them anywhere else? In your armpits?’

‘Not that I am aware of. I didn’t notice any in the bath.’

She took a narrow-toothed comb from her mother’s dressing table and used it to drag the powder through his hair, her throat burned by the bile rising from her stomach. She went back to the window and waited for the insects to die and then picked them out, dropping them into the dressing table dish she used to hold her hairpins.

‘I’m sorry, Katharina.’

She went to the bathroom, bumping the door against her mother who was on her hands and knees mopping the muddied floor with a cloth. Katharina stepped over her and scraped the lice into the toilet.

‘You’ve got your hands full with that one, Katharina.’

She flushed, scrubbed furiously at the comb and dish, and then at her hands.

‘He said that he had none under his arms.’

‘What about his groin?’

‘I didn’t ask.’

‘Maybe you should.’

‘I don’t know that I can.’

‘I’ll soak his uniform in the bath. You can do his pack. They’ll be in there too.’

‘We’ll need more powder.’

‘I’ll look for some in the morning.’

Katharina stared at herself in the mirror, certain that her skin had aged since his arrival.

‘I hope you’re not right, Mother. About the doctor’s son.’

She ran her fingers across her now pale lips, but decided against adding more lipstick.

‘I’d better go back to him.’

‘I suppose you had.’

‘Goodnight, Mother.’

‘Goodnight, Katharina.’

He rose to his feet as she walked in, clicked his heels and bowed.

‘My dear new wife, will you ever forgive me?’

‘I doubt it.’

He ran his fingers across her forehead, flattening the deep furrows.

‘I’m not as awful as you think,’ he said.

‘Aren’t you?’

She moved away from him, back towards the window.

‘What were you expecting, Katharina? Casanova? You picked me from a bloody catalogue.’

‘And it was obviously a lousy choice.’

‘Thank you.’

‘You arrived here covered in lice and stinking so badly that I thought I would vomit. What was I expecting? Somebody who had bothered to wash.’

‘I didn’t want to leave the train, Katharina.’

‘What?’

‘I was supposed to get off in Poland, at the cleansing station, but I was afraid that they would send me back. That I wouldn’t get home. So, I stayed on the train. And nobody noticed.’

‘I bloody did.’

He laughed, and covered his face with his hands.

‘I’m sorry, Katharina. I just had to get away from there.’

She sat down on the end of the bed.

‘I’m sorry, Peter. I didn’t expect it to be this difficult. This awkward.’

‘What had you expected?’

She smiled.

‘I don’t know. Flowers. Chocolates. Not head lice.’

He sat down beside her. She moved away.

‘I don’t want to catch them.’

‘You nearly killed me with the powder, so I doubt that any of them has survived.’

She laughed.

‘You’re beautiful when you laugh.’

‘Not just pretty?’

‘No. Beautiful. How many men did you write to?’

‘Just to you. Did you write to other women?’

‘No.’

He reached for her hand and she let him take it.

‘When was your photograph taken?’ she said.

‘Just before I left for Russia.’

‘It’s a nice photograph.’

‘Nicer than me in the flesh.’

‘I don’t know. Just different.’

‘How?’

‘Your face is different. Kinder, maybe.’

‘So you’re disappointed?’

‘I don’t know yet.’

‘It’s a hard place, Katharina.’

‘I can smell that.’

They lay across the bed that she had made up that day, working with her mother, an embarrassed silence between the women as they tucked and folded the sheets. She moved her hair away from his.

‘What’s it like on the front?’ she said. ‘Johannes tells us very little in his letters.’

‘Let’s talk about something else.’

‘Like what?’

‘Like you as a little girl.’

‘I lost all the races. There is nothing more. That’s all I was – the girl who came last in everything. Except sewing and cooking – I was always good at those. What about you? What were you good at?’

But he was asleep. A light snore rose from him. She prodded him.

‘There are pyjamas under the pillow for you.’

He put them on, his back to her.

‘I’m sorry, Katharina. I’m exhausted.’

‘It’s fine.’

He kissed her on the cheek, this man in her brother’s pyjamas, and fell back to sleep. She sat at the dressing table to brush her hair, to look at herself, this woman married to a man she did not know. She pulled on a long nightdress and climbed in beside him.

4

Shortly before dawn, Faber woke, sweating and panting, his body no longer accustomed to comfort and warmth. He threw off the covers and lay still, quietening his breath, absorbing the coolness of the dark air.

Katharina lay beside him, still asleep. He turned away from her and put his feet on the floor. He would leave, slip away to his parents’ living room of soft chairs and matching crockery. He stood up but then slumped back down again. Her mother had his uniform. He slapped his head onto the pillow. Katharina woke.

‘Are you all right?’ she said.

‘I’m fine. Go back to sleep.’

‘Are all those lice dead?’

He laughed.

‘They’re well murdered.’

‘I’m glad.’

She moved across the bed towards him, and set her hand on his chest.

‘It’s all a little odd, isn’t it?’ she said.

‘We didn’t start well, did we?’

‘No.’

‘So what do we do now?’

‘I don’t know.’

He sat up.

‘I’m hungry, Katharina.’

‘I’ll go and see what there is.’

He lit a cigarette and looked through the dawn light at the room, at the sagging curtains and the cheap, functional dressing table. His parents’ furniture was old and ornate, passed from one generation to the next.

She returned with a hot drink and bread.

‘It’s not the real coffee. Father must have taken it to his room. He’s very protective of anything given by Dr Weinart.’

‘Who is Dr Weinart?’

‘I’m not really sure. I know they were together in the last war. I haven’t met him.’

Faber drank.

‘My God, Katharina. It’s disgusting.’

‘They say that if you think of it as coffee, then it tastes like coffee.’

‘I’m not that bloody mad. Not yet anyway. We get better than this on the front.’

‘I suppose that’s a good thing. You need it more than we do.’

‘It is until I get leave.’

He set down the cup and plate and pulled her to him.

‘So, you were telling me what you were like as a girl.’

‘Yes, and I was so interesting that you fell asleep.’

He nuzzled his face into her hair.

‘I am so sorry, Katharina Spinell. I will not fall asleep again. Now, tell me what were you like?’

‘I don’t know. I was always good, but my mother adores my brother.’

He dropped his head onto the pillow and snored. She laughed and slapped him on the arm.

‘You’re so unfair to me,’ she said.

He kissed her.

‘So you were a daddy’s girl?’

‘I suppose so. And you?’

‘I was never a daddy’s girl.’

They laughed, and he kissed her on the cheeks and lips, moving to her neck.

‘And you, Peter Faber?’

‘All I have done is march. Left right, left right. Youth movement, war, pack on my back – it’s all I have done so far in my life.’

She kissed his lips, his cheeks.

‘You must have done something else,’ she said.

He slipped his hand under her nightdress.

‘Let me see if there is anything else I can remember.’

He ran his hands over her bottom, stomach and breasts.

‘I’m remembering,’ he said.

She opened the buttons of her brother’s pyjamas and fingered his chest.

‘We need to fatten you up a bit, Mr Faber.’

He took off the pyjamas and pushed up her nightdress.

‘You do that, Katharina Spinell. Turn me into a doctor’s fat son.’

They giggled and she parted her legs.

‘Next time I’ll bring you flowers and chocolates,’ he said.

‘I only like dark chocolate. And white flowers.’

‘You’re a very fussy woman, Mrs Faber.’

‘I’m very particular, Mr Faber.’

When it was fully bright outside, she pulled a robe over her nakedness and went to the kitchen.

‘Katharina, you should dress for breakfast,’ said Mrs Spinell.

‘I’m not staying.’

‘You have to eat breakfast.’

‘I’ll take food back to Peter.’

‘Sit down and have yours first.’

‘No, I’ll take mine too. Is there any ham?’

‘Hopefully later today.’

Her father put down his newspaper.

‘Be a good girl, Katharina, and do as your mother asks.’

She moved towards the hob.

‘How did you sleep, Mother?’

‘Not very well. Your bed is very small.’

‘I’ve been saying that for years. It’s a child’s bed, Mother.’

‘You’re still my child, Katharina.’

‘For God’s sake, Mother.’

Mr Spinell rustled the newspaper.

‘Fetch Peter and have breakfast with us,’ said Mr Spinell.

‘He would rather eat in the room, Father.’

‘Your mother has set the table for you both.’

‘I’ll take the tray.’

She hummed to discourage further interference, loaded coffee, cheese and bread onto the tray and went back to the room. Faber was waiting for her, smiling, tugging at her robe as she set down the tray, sliding it off her as she poured coffee. Dr Weinart’s coffee. He buried himself in her.

He sat again on the chair under the light and she, humming, picked lice from his hair.

‘I should cut it,’ she said.

‘Are you any good?’

‘Would you notice?’

She cut the fringe dangling from his receding hairline, and sheared the back of his head with her father’s clippers. She wiped the loose hairs from his neck and face, kissed him and left the room. She returned with a basin of steaming water.

‘You will want for nothing,’ he said.

‘All I want is to be away from my parents.’

‘I’ll buy a big house with a garden.’

‘How, as a teacher?’

‘I’ll find a way.’

She knelt in front of him, lifted and lowered his right foot, then his left, into the water, splashing his shins and calves, rubbing her hands over his ankles and heels, over his bruises and calluses, squeezing and releasing the flesh of each toe until she could feel the weight of his fatigue. She dried each foot and led him to bed, tucking him between the still-damp sheets. She went back to the kitchen.

‘He’s exhausted,’ she said.

‘I’m sure.’

‘What’s wrong, Mother?’

‘Nothing.’

‘Fine, then.’

Mrs Spinell stabbed at a potato with her rusting peeler.

‘This is not a hotel, Katharina.’

‘I’m aware of that.’

‘Fine, then.’

‘Fine, what?’

‘A little more decorum and respect for your parents would be appreciated.’

‘Yes, Mother.’

‘Dinner will be at six, Katharina.’

‘Yes, Mother.’

At dinner, they held hands beneath the table, tangled feet and answered any questions put to them. When it was over, he undressed her under the bedroom light and gently unpicked the pins from her hair, watching as each lock fell the length of her unblemished back.

The following evening, after dinner, Mr Spinell insisted that Faber accompany him to the city centre.

‘Dr Weinart will be there.’

‘But we had plans, Father.’

‘Peter needs to meet the doctor before he goes back, Katharina.’

Faber took her brother’s coat, but walked a little behind her father through silent, shuttered streets. Mr Spinell halted in front of the opera house, its damage almost fully repaired.

‘You see, Faber, we are invincible. Anything they bomb, we fix.’

They walked down steps into a fuggy warmth of men. Faber stood at the edge of the crowd, envying its drunkenness. Mr Spinell disappeared for some time and returned with four tankards of beer.

‘Get stuck in, Faber.’

They toasted Katharina, and Faber was soon surrounded by men in brown uniform, all older than he, lauding his efforts at Kiev.

‘You remind us of ourselves,’ said Mr Spinell, ‘only we want you to do better. To hammer them all this time.’

‘I can’t do any worse.’

They laughed, raised their glasses and drank. Dr Weinart joined them.

‘Your father-in-law has told me all about you, Mr Faber. It’s an honourable thing you have done.’

‘What is?’

‘Marrying Miss Spinell. Securing the future of our nation.’

‘We are very happy, Dr Weinart.’

‘Of course you are.’

The doctor sipped from his small glass of beer.

‘You have chosen a good family, Mr Faber. Mr Spinell works very hard for me, and I hugely appreciate his support.’

‘I’m glad.’

‘So the next thing, Mr Faber, is to find you some work. Good, useful work.’

‘Like what?’

‘What are your interests?’

‘I’m a teacher.’

‘I know that, just like your father.’

‘And my grandfather.’

‘A fine tradition, but you can break free if you want to.’

‘What do you mean?’

‘Decide for yourself. It is your life, Mr Faber. Not your father’s. Or your grandfather’s.’

Faber drew from his tankard.

‘Have you anything in mind?’

‘Berlin will soon be the centre of the world, Mr Faber.’

‘Indeed it will, Dr Weinart,’ said Mr Spinell.

‘We will need to educate our new empire, to communicate to our new citizens what it is to be a true German.’

‘So not farming?’

Dr Weinart laughed.

‘You don’t look like a farmer to me.’

‘Mr Spinell thought that I could be turned into one.’

‘I doubt it.’

‘I still hold out hope, Dr Weinart.’

They all laughed.

‘Will I be well paid?’

‘You’ll be looked after.’

‘Enough for a house and garden?’

‘We take good care of our own, Mr Faber.’

The speeches began and Faber moved away to stand by the wall. Dr Weinart, his black uniform impeccably pressed, came and stood beside him.

‘You need some more time with us, Faber. I’ll have your leave extended.’

‘You can do that?’

‘I’ll get you another week. Ten days, maybe, so that you can come out with us. Let me buy more beer.’

Faber toasted Dr Weinart, drank and joined in the singing, and the shouting.

5

They took the train to the Darmstadt house hidden from the road by a dense laurel hedge. His mother rushed at him, hugging him and chiding him for the surprise. She straightened her skirt and hair when she caught sight of Katharina.

‘Excuse me, I’m Peter’s mother. I had no idea that he was home.’

‘Mother, this is my wife, Katharina Spinell.’

Mrs Faber snorted.

‘Is this a joke, Peter?’

‘No.’

‘You’d better come in. I’ll make some coffee. Your father will be home soon.’

‘Good.’

‘We’ll use the living room.’

She went before them, hurrying to open the curtains.

‘It’s a beautiful room,’ said Katharina.

‘Thank you.’

‘My mother keeps the curtains drawn to protect the furniture from the sun.’

‘And the books, Peter,’ said his mother.

‘It works,’ said Katharina. ‘Everything’s perfect.’

‘Like a museum,’ said Faber.

‘You’re being rude,’ said his mother.

‘Don’t think of doing this in our house, Katharina. I want the sun in every room.’

Faber looked around. Nothing had changed. It never did. He led Katharina to the sofa, sat her down, kissed her, and followed his mother into the kitchen.

‘You should have told us, Peter. Warned us.’