1,99 €

Niedrigster Preis in 30 Tagen: 1,99 €

Niedrigster Preis in 30 Tagen: 1,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Booksell-Verlag

- Kategorie: Poesie und Drama

- Sprache: Englisch

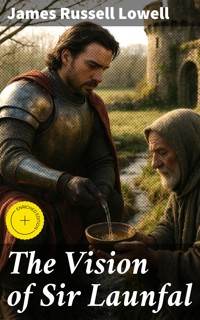

In "The Vision of Sir Launfal," James Russell Lowell weaves a rich tapestry of Arthurian legend, employing a lyrical style infused with moral depth and Romantic sensibility. The poem chronicles Sir Launfal's quest for the Holy Grail, traversing themes of idealism, spirituality, and social responsibility. Set against a backdrop of medieval chivalry, the poem invites readers to explore the juxtaposition between earthly riches and spiritual fulfillment, all while employing vivid imagery and an allegorical narrative that speaks to the human condition. Lowell's command of language and rhythm transforms this tale into not just a quest for a relic but a critique of the societal values of his time. James Russell Lowell (1819-1891) was a prominent American Romantic poet, critic, and editor whose works often reflected his deep engagement with social and political issues. An influential figure in the Transcendentalist movement, Lowell's dedication to social reform and his understanding of human compassion resonate throughout his poetry. The creation of "The Vision of Sir Launfal" was likely influenced by his advocacy for moral improvement and his belief in the capacity for personal and societal transformation. Highly recommended for readers interested in the intersection of literature and morality, "The Vision of Sir Launfal" offers profound insights into the quest for meaning amidst a complex world. Lowell's expert craftsmanship and the poem's enduring themes make it a significant read for those who appreciate the interplay of ethics and artistry in literature. In this enriched edition, we have carefully created added value for your reading experience: - A succinct Introduction situates the work's timeless appeal and themes. - The Synopsis outlines the central plot, highlighting key developments without spoiling critical twists. - A detailed Historical Context immerses you in the era's events and influences that shaped the writing. - A thorough Analysis dissects symbols, motifs, and character arcs to unearth underlying meanings. - Reflection questions prompt you to engage personally with the work's messages, connecting them to modern life. - Hand‐picked Memorable Quotes shine a spotlight on moments of literary brilliance. - Interactive footnotes clarify unusual references, historical allusions, and archaic phrases for an effortless, more informed read.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

Ähnliche

The Vision of Sir Launfal

Table of Contents

Introduction

At its heart, The Vision of Sir Launfal explores how true nobility arises not from outward splendor or distant quests, but from an awakened compassion that reshapes perception itself, inviting a knight and the reader to measure wealth by human kinship and to discover spiritual meaning in the ordinary as surely as in the legendary.

James Russell Lowell, a leading American poet of the nineteenth century, first published The Vision of Sir Launfal in 1848 amid the flourishing of American Romanticism. The work is a narrative poem that draws on Arthurian material while speaking to contemporary moral concerns. Its imaginative landscape entwines medieval chivalry with distinctly American scenes, especially through lyrical seasonal preludes that frame the tale. Readers encounter a fusion of romance, moral reflection, and nature writing. The result is a poetic experience that feels at once traditional and new, placing a timeless quest within the moral and aesthetic interests of Lowell’s mid-century audience.

The premise is straightforward yet suggestive: a knight resolves to seek the Holy Grail and is confronted, even before he departs, with a test of values near at hand. Lowell presents this as a visionary journey, moving between vivid description and contemplative commentary. The voice is elevated but welcoming, combining narrative momentum with meditative pauses. The poem invites readers to inhabit a sensibility that is reverent toward nature, attuned to conscience, and curious about the difference between appearances and realities. Its mood shifts from rapture to austerity, mirroring seasonal changes and the inner transitions of a seeker poised between pride and humility.

Central themes include charity, humility, and the redefinition of wealth. The poem contrasts outward magnificence with inner generosity, asking how moral insight alters what we consider valuable. It examines how vision—spiritual, ethical, and aesthetic—enables us to recognize dignity where custom or habit might overlook it. Nature functions as a moral teacher, its seasons echoing states of the soul. By adapting an Old World legend to American textures and concerns, Lowell suggests that the highest ideals are not bound to courts or banners, but emerge wherever conscience attends to the claims of neighbor, community, and the quietly transformative power of empathy.

Lowell’s style blends narrative clarity with lushly descriptive passages. The seasonal preludes, especially, establish atmosphere and frame of mind, providing a sensuous register against which the moral drama unfolds. Images of light and cold, stone and water, verdure and barrenness, trace the movement from idealized ambition toward sober recognition. The poem’s symbolism is accessible without being reductive, allowing readers to appreciate both the story and its allegorical dimensions. While indebted to romantic conventions, the language retains a conversational warmth. This balance between elevated vision and approachable cadence makes the poem inviting to new readers and rewarding upon return engagements.

For contemporary audiences, the poem’s relevance lies in its insistence that attention and compassion recalibrate value. In a world preoccupied with status, speed, and distant abstractions, Lowell directs the gaze homeward, to immediate responsibilities and shared humanity. The work also speaks to ecological awareness: nature is not a backdrop but a participant in moral discernment. Its fusion of mythic quest with local, everyday encounters suggests that profound ideals become real in small, tangible acts. Readers may find in it both comfort and challenge—a call to see afresh, and to consider how perception itself can be an ethical practice.

Approaching the poem, notice how the seasonal frames shape expectation, and how the narrative contrasts splendor with simplicity to test assumptions about honor. Attend to the interplay of dreamlike vision and concrete detail, and to the way Arthurian romance is refitted to American scenes. The experience offered is reflective rather than plot-driven, inviting slow reading and openness to suggestion. Without disclosing its later turns, it is enough to say that the quest begins at the threshold, where recognition and responsibility first appear. The Vision of Sir Launfal rewards readers who seek beauty joined to conscience, and story joined to moral insight.

Synopsis (Selection)

James Russell Lowell’s The Vision of Sir Launfal is a narrative poem that blends Arthurian quest with New England landscape to explore the meaning of true wealth and nobility. Presented in two parts framed by lyrical preludes, it follows a knight who sets out to seek the Holy Grail while the poet reflects on nature, conscience, and charity. The work contrasts outward splendor with inward worth, linking seasonal change to moral insight. Through episodic encounters and meditative passages, the poem traces a movement from pride to humility and from material measures of value to a spiritual understanding grounded in compassion and shared humanity.

The poem opens with a summer prelude that celebrates June’s abundance. Fields, rivers, and sunlight become emblems of generosity, suggesting that nature’s largesse offers a model for human giving. The prelude contrasts bright, unbought riches with the cold grasp of gold, introducing a moral lens that privileges inner radiance over external show. These reflections set the stage for the narrative by emphasizing how a heart attuned to simple beauty perceives a richer world. The tone is expansive and hopeful, preparing readers to see the coming quest not only as a literal search but as a test of the hero’s capacity to recognize true treasure.

Sir Launfal, a youthful knight associated with King Arthur’s court, prepares for a holy enterprise: to find the Grail, the emblem of divine grace. Clad in glittering armor and buoyed by high purpose, he departs his ancestral hall confident in honor and lineage. The scene emphasizes ceremonial pomp and the shining prestige of chivalry, underscoring the distance between public glory and private duty. Lowell frames this departure as a threshold moment: the world before him seems friendly and fair, and the dream of a grand discovery beckons. Yet, as he moves from gate to road, his readiness to meet need is quickly tested.

At the castle gate, a destitute outcast supplicates alms. The encounter presents a stark contrast between the knight’s magnificence and the beggar’s misery. Sir Launfal responds with pride and distance, offering a token without true fellowship. The moment is quiet but decisive, exposing a moral blind spot that accompanies his outward quest. He rides on, keeping his eyes fixed on a distant, exalted goal, while the human claim close at hand remains unmet. This early scene crystallizes the poem’s tension: the allure of lofty missions versus the immediate demands of kindness that test the heart more searchingly than pageantry.

The quest carries Sir Launfal through time and changing landscapes, yet success proves elusive. The poem treats his search as both literal journey and inward discipline, and it suggests that sacred visions cannot be purchased by status or force. Though he persists, the Grail does not appear in the manner he imagines. The radiance he seeks stays veiled, and the promises of outward valor grow faint. This section develops the idea that external striving, if unaccompanied by compassion, yields a barren harvest. What seemed certain when he set out becomes uncertain, and the assurances of youth give way to a more chastened awareness.

A second prelude shifts the season from summer’s plenty to winter’s austerity. Snow, iron cold, and dim light convey hardship and want, while hearth-warmth offers a counterimage of shared comfort. The mood is contemplative and severe, focusing attention on those who endure cold and hunger. In this stripped landscape, pretense falls away, and the poem’s ethical concerns sharpen: what sustains life is not finery but the mutual aid people extend to one another. The prelude aligns natural scenes with moral instruction, preparing for the narrative’s return to Sir Launfal under altered conditions, where external supports have thinned and inner resources must speak.

Sir Launfal comes back changed by time and circumstance. Humbled and poorer, he revisits the threshold where his proud departure began. The same figure in need appears again, now amid winter’s bite. This time the knight meets the moment differently. He offers what little he has, not as a gesture from above but as a shared meal and warmth, acknowledging kinship rather than distance. The exchange is simple and direct: nourishment, shelter, and regard flow between them. This act, grounded in equality, marks a turning point. It demonstrates that generosity is measured not by sum but by spirit, and that fellowship transforms giver and receiver alike.

In the wake of this compassionate act, the poem’s central insight arrives as a vision of what the Grail truly signifies. Without relying on spectacle, the scene discloses that the sacred is encountered where need is met with love. The knight recognizes that the quest he pursued across distances is fulfilled in the nearness of humane service. The grandeur he sought outwardly proves to be an inward light, and the symbols of knighthood take on new meaning. Boundaries soften, and gates once closed open in a different sense. The poem reframes victory as a change of heart that sees value in every neighbor.

The closing movement affirms the poem’s message: genuine wealth resides in charity, and the highest rite is the sharing of what we have with those who lack. By aligning summer’s generosity and winter’s severity with the stages of Sir Launfal’s growth, Lowell presents a moral vision both social and personal. Pageantry yields to humility, rank to fellowship, and distant ambition to immediate service. The Vision of Sir Launfal thus offers a concise parable of ethical awakening, arguing that paths to the holy run through everyday compassion. What endures is not gold or fame, but the warmth we bring to another’s need.

Historical Context

James Russell Lowell sets The Vision of Sir Launfal in a mythic, medieval Britain centered on King Arthur’s Camelot, yet frames it with vivid New England seasonal preludes that locate its moral inquiry in nineteenth-century America. The poem’s June and winter vistas echo Massachusetts landscapes familiar to Lowell in Cambridge and Boston, where he lived and worked in the 1840s. Within the narrative, a knight’s quest for the Grail becomes a parable enacted at a castle gate, where a leper stands as the abject outsider. The temporal doubleness—Arthurian chronotope and contemporary ambience—allows Lowell to transpose pressing American social questions into a universal moral register of charity, justice, and civic responsibility.

Abolitionism was the dominant social movement shaping Lowell’s conscience in the 1840s. The American Anti-Slavery Society, founded in Philadelphia in 1833 under William Lloyd Garrison, pressed for immediate emancipation and equal rights, while the Boston Vigilance Committee and state societies organized resistance to slave catching. After Britain’s 1833 Slavery Abolition Act, American reformers intensified efforts at home. Lowell, influenced by his abolitionist wife Maria White, published Stanzas on Freedom in 1843 and The Present Crisis in 1844, enlisting poetry in reform. In 1848, the year Sir Launfal appeared in Boston, he took up the editorship of the National Anti-Slavery Standard in New York. The poem’s ethic of shared humanity implicitly rebukes a slave system that commodifies persons.

Legal and political flashpoints in the 1840s sharpened antislavery urgency. Prigg v. Pennsylvania (1842) limited state interference with the 1793 Fugitive Slave Act, spurring northern personal liberty measures and fueling Boston’s antislavery mobilization. The congressional gag rule on antislavery petitions, enforced from 1836 until its repeal in 1844, dramatized the suppression of moral debate. The annexation of Texas in 1845 and the push to extend slavery westward escalated sectional conflict. In Massachusetts, figures like Charles Sumner articulated a peace-and-liberty program, exemplified by his 1845 oration The True Grandeur of Nations. Against this backdrop, Lowell’s parable of a leper welcomed as Christ in disguise makes the Grail stand for a justice grounded in compassion rather than law or conquest.

The Mexican–American War (1846–1848), sparked by the annexation of Texas and a boundary dispute over the Rio Grande, ended with the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo on 2 February 1848. The United States acquired vast territories—present-day California, Nevada, Utah, and parts of Arizona, New Mexico, Colorado, and Wyoming—for $15 million; roughly 13,000 American soldiers died, most from disease. The war intensified disputes over whether slavery would expand westward. Lowell denounced the conflict in The Biglow Papers (1846–1848), satirizing expansionism and martial glory. Sir Launfal, published the same year the treaty was signed, reframes national ambition through a spiritual economy: wealth and victory are empty without mercy, and true honor lies not in conquest but in recognizing the poor as kin.

Urban poverty and charitable reform in Boston and Cambridge in the 1830s–1840s formed a concrete social horizon for Lowell’s meditation on almsgiving. Industrialization and migration swelled Boston’s population from about 93,000 in 1840 to roughly 137,000 by 1850, straining relief systems. The Boston Provident Association (founded 1835) coordinated aid, while the House of Industry in South Boston (1823) and almshouses sought to distinguish the deserving from the undeserving poor. In 1847, amid disease brought by crowded ships, quarantine facilities were expanded on Deer Island. Public debate turned to scientific charity and moral uplift. Sir Launfal’s leper scene rebukes transactional philanthropy: the gift without the giver is bare, insisting that personal fellowship, not institutional sorting, fulfills social duty.

The Great Irish Famine (1845–1852) sent tens of thousands of immigrants to New England, with a marked surge in 1847 known as Black ’47. Boston’s wards absorbed impoverished newcomers facing disease, job competition, and religious prejudice. Nativist sentiment grew through the late 1840s, presaging the Know-Nothing ascendancy of the mid-1850s. Municipal relief, Catholic charities, and ethnic networks struggled to meet need as boardinghouses and docks became sites of contagion and conflict. Against a climate of suspicion toward the foreign-born poor, Lowell’s poem models a radical hospitality: the knight’s sacramental recognition of the despised stranger anticipates a civic ethic that crosses class, ethnic, and confessional boundaries in an era of volatile urban change.

Territorial slavery politics crested as Sir Launfal reached readers. The Wilmot Proviso, introduced in Congress by David Wilmot on 8 August 1846 and repeatedly advanced in 1847, sought to bar slavery from any lands seized from Mexico; it passed the House but failed in the Senate. The Free Soil Party formed in Buffalo in August 1848 under the slogan Free Soil, Free Speech, Free Labor, and Free Men, nominating Martin Van Buren with Charles Francis Adams of Massachusetts as running mate. In Massachusetts, antislavery Whigs and Democrats fractured along these lines. While Sir Launfal is allegorical, its 1848 insistence that true treasure lies in just relations resonates with Free Soil warnings against turning new territories into markets for human bondage.

The poem functions as social and political critique by translating mid-century controversies—war, expansion, slavery, and urban destitution—into a moral litmus of charity. By making the Grail attainable only when Sir Launfal shares bread and water with a leper, Lowell exposes the vanity of wealth, conquest, and respectability divorced from human solidarity. The narrative condemns almsgiving as display, denounces class arrogance at the gate, and challenges a polity that prizes property and empire over persons. In 1848, when the nation debated dominion and the status of labor, the poem insists that justice begins at the threshold with the excluded, and that a republic’s grandeur is measured by its mercy.