10,79 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Salt

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

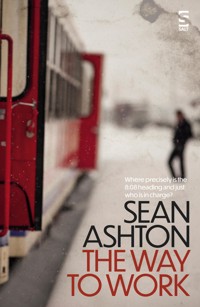

Have you ever boarded your morning commute and wished you'd never arrive at your destination? That is what happens to the protagonist of The Way to Work. Having boarded what he assumes to be his usual 8:08 service, he soon discovers that all is not as it first seemed. Does this train stop at any station? Do the carriages ever come to an end? And where is the colleague he thought he saw, as he took his place in the quiet coach? Our narrator reflects on his job as salesman for a cat litter manufacturer as he wanders down-train in search of answers – yet the sliding doors that close behind him appear to be malfunctioning, and every person he meets seems to remember very little of their past. Seduction, destiny and salvation all come into play as this relentless novel unfolds, and we discover precisely where the 8:08 is heading and just who is in charge.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Ähnliche

For Anat

‘The madman’s exclusion must enclose him; if he cannot and must not have another prison but the threshold itself, he is kept at the point of passage.’

Michel Foucault, Madness and Civilisation

CONTENTS

I

BOARDING

1

It was Tuesday when I set out, and I hurried for the train as usual, keen to secure my favourite seat, the one at the rear of Coach B, the designated quiet coach. The quiet coach was barely half full, and it looked like it was going to be a tolerable, perhaps even a pleasant journey. As we left the station and accelerated through the suburbs, past the football stadium and industrial estates, I noticed there were no announcements. Usually, there’s a constant sizzle of electricity coming from the speakers, that threatens to bloom into a long-winded enumeration of station stops, reminders to keep one’s personal possessions alongside one at all times, warnings not to smoke anywhere on board, including the toilets and vestibule areas, or to knowingly permit smoking anywhere on board; but the public address system didn’t seem to be working, and not without relief did I reflect that we wouldn’t have to endure the Guard’s party piece, which he always seemed to enjoy more than he should.

I’d nearly run into Mark Ramsden on the way to the station. He lived barely a mile from me. Our routes converged in the market square and that morning I’d only just managed to avoid him. For a long time it wasn’t clear if I was avoiding Ramsden or Ramsden was avoiding me. It took us a while to work out that we were both avoiding each other. If I spotted him first, I’d duck down a side street and sprint to the rear of the station while he continued to the main entrance. Ramsden favoured a similar method. If I thought he’d seen me first, I’d linger under an awning pretending to check my phone: a clear signal to Ramsden that he should take the initiative. But sometimes we’d see each other at the same moment, and it was unclear who should hang back and who should proceed to the station. Sometimes I’d stop and rummage through my bag to make it look like I’d forgotten something – anything to prevent us running into each other. It was just two men trying to get to work, but we seemed to resent the similarity of our routines.

That morning, I’d outmanoeuvred Ramsden, spotting him through a side street before the market square and sprinting to the station. I’m pretty quick for a 45-year-old. There was plenty of time to get my ticket and pastry prior to boarding, and I still had a minute or two to get comfortable before my colleague came through the sliding door.

There was an awkward moment when, having taken his own seat halfway down Coach B, Ramsden had to go into the vestibule to take a phone call. He really ought to have chosen the front vestibule at the other end, but his path was blocked by passengers still boarding, so he was forced into the rear one where I was sat, and as he went past he shot me a lugubrious look. Despite our reluctance to interact at that time of the morning, we both favoured the same coach. In point of fact, we coveted the same seat: the one at the back, on the right, with the extra leg room: 77a. You would think that, if we had to sit in the same coach, we would have nominated a favourite seat as far as possible from the other man. But we seemed to need this tension, it seemed to serve some purpose.

I wasn’t looking forward to the conversation we’d have to have once Ramsden had completed his call. Because once we’d boarded the train, different rules applied. It was childish to ignore each other for the whole journey, so at some point – usually on my way to the buffet car – I would nod at Ramsden, or Ramsden would nod at me. It depended on who’d got seat 77a. It was understood that some concession was expected of the victor. A smile was usually enough to defuse the awkwardness, at most a remark about nothing in particular: as long as you kept moving as you talked and said something utterly banal, the emptiness of the gesture was clear. There always was a danger, of course, that your remark would be more interesting than you intended or – worse still – misheard and you’d have to repeat it, accidentally initiating a longer conversation when the real purpose of your exchange had been to eliminate the need for conversation altogether. I’d seen this happen to other work colleagues, who clearly would have preferred to sit apart but felt compelled to sit together for no other reason than that they were colleagues. Ramsden and I were above all that. We had an understanding.

Anyway, there we were, in Coach B, each in his bubble of pre-work freedom. I’d turned my phone off, fearing a call from Dan Coleman, who regarded the journey as company time. This was a legacy of his predecessor, the late Fred Teesdale, who hadn’t cared when we came in as long as we did our jobs. It was always understood that we could catch the later 8:08 train, rather than the 7:08. Dan had continued to allow this on the understanding that we made ourselves available for consultation, but I always turned my phone off. Inevitably, when I went through the ticket barrier at the other end, I’d find a text message from my line manager: I TRIED TO CALL BUT YOU’RE NOT PICKING UP?!?! Or something like that. Now, I have to confess that Mark Ramsden had stolen a march on me here. He was able to give the impression to Dan Coleman that his working day began on that 8:08 train, simply because he always answered his calls. And his geniality was very convincing when he picked up. I’d watched him nodding and smiling, nodding and smiling, as though our line manager were right there with him in the carriage, before giving his phone the finger the very second he hung up. It was true that Mark Ramsden was able to sustain the illusion of being more conscientious than me, but at what cost to his personal wellbeing?

Where were we? Yes, we had just pulled out of the station. We’re just going past the football ground, and it’s starting to rain. Mark Ramsden is there in the vestibule, taking his call, possibly discussing strategy with Dan Coleman for the meeting later that morning. It was an important day: some prospective new clients were coming over from Germany. There was to be a briefing at 11:30 to discuss strategy. The plan was that I was to meet them in the foyer after lunch and take them on a tour of the facilities. I had misgivings about this arrangement. I’d go so far as to say that our prospective German clients had been enticed over to England on false pretences. I knew for a fact that the price we had quoted them was lower than that which Dan Coleman would later write on a piece of paper and push across the boardroom table, and my role, as I led the German delegation around, would be to prepare them for this surprise by dropping hints about our rising production costs. The majority of our clients had no idea how many stages were involved in our manufacturing process, and Dan Coleman’s thinking was that they would be less likely to baulk at our final figure if we showed them the full scope of our operation. After the tour of the facilities, this hospitality was to be extended into the evening. Everyone had been asked to prepare for an overnight stay, Dan Coleman having arranged to take our guests out to dinner. Hence my overnight bag. I noticed that Ramsden had his too.

Ten minutes passed before I realised Ramsden was no longer in the vestibule behind me, that he had managed to end his call and creep back to his seat without my noticing. I felt a surge of admiration for my colleague here: just when you thought you’d set new levels of detachment and aloofness, Ramsden upped the ante. But no: he was not in his seat. He wasn’t anywhere in Coach B. I thought maybe he’d gone to the buffet car or the toilet, but the ‘engaged’ light wasn’t on and he never went to the buffet car this early. I’ve watched Ramsden closely over the years and am wise to his routine: a brief look at the newspaper on boarding, a quick scroll down his emails. But that morning he’d given me the slip, and it bothered me not knowing where he was. I knew I wouldn’t be able to eat my pastry and enjoy my crossword, not till he was back in his seat where he belonged, not till we’d got the formalities out the way.

2

Before going any further, I suppose I should tell you something about cat litter. It’s not strictly germane to the rest of my account, but it is my vocation, after all. The first recorded use of cat litter is during the reign of Neferirkare II in ancient Egypt c. 2040 BC. This is not surprising given that cats were venerated in that region. We know from the hieroglyphs found in his tomb that Neferirkare’s cats were not suffered to bury their waste in ordinary desert sand – that mud was transported from the Nile delta to produce a blended compound. Archaeologists have recreated this compound and found it to be only 26% less efficient at neutralising odour than modern-day equivalents. I don’t go so far as to call him the sole pioneer in this area, but we may speculate that Neferirkare was more discerning than most in his quest for a satisfactory formula. The hieroglyphs tell a story of constant experimentation with different proportions of dry and wet material, organic and inorganic, granular and smooth, the aggregate refined with crushed rock, shredded palm leaves, sawdust and bone meal, all in honour of his prize puss Imhotep, whose mummified remains are exhibited alongside Neferirkare’s own at the Egyptian Museum in Cairo.

I quote from Fred Teesdale, who made me learn all this by heart on my first day at work nearly fifteen years ago. I once heard him tell a more nuanced version to some Belgian clients, which had it that Neferirkare was also the first to coin the term ‘clumping’, and which everyone agreed was a more effective sales pitch than the truth. Things were different then. I’d go so far as to call it a golden era.

I should really say a bit more about what I’m leaving behind. Or rather, who. I loved Fred, and Bob Buchanan was entertaining in doses, but Mick Leadbetter? Don Drinkwater? Les Cundy, Jack Meanwell and all the rest of them? I don’t think I’ll miss them, nor they me. And as for Dan Coleman, I should really have left when he took over.

Mark Ramsden was the only other exception. Despite everything, I have always respected Mark Ramsden. I have always admired his approach. In some ways it resembles my own approach – in some ways we are similar. There are few people with whom one can have a completely tacit understanding, but Ramsden is just such a man. He understands that he must not try to understand me, just as I understand that I must not try to understand him. Ramsden might put it differently, but that is my reading of the situation.

As colleagues, naturally we have often been required to operate in concert, but always preferred to do so at a distance. We shared an employer but saw no reason why the right hand had always to know what the left was doing. Our ability to predict what each other would do was far from telepathic, but I wouldn’t have dreamt of phoning Ramsden to check whether the thing to be done had in fact been done by him, nor he me. We preferred to rely on instinct, and on those occasions when instinct led to our replicating a task, the results were not uninteresting – I go so far as to call them enlightening.

I’m not sure Dan Coleman saw it that way. But give him his due, it was not long before he managed to exploit this synchronicity. It’s worth my fleshing this out, I think; I can see that an example is called for.

‘What does a cat like to do in the bathroom?’ he asked us one afternoon.

This was more than five years ago now. He hadn’t been with us long, Dan – a few months at most – but he’d changed the way we did things already, substituting a more aspirational mindset for the easy-going complacency of Fred Teesdale. This euphemism said it all. What was wrong with ‘litter tray’?

‘I ask you again,’ he said, when no replies were forthcoming: ‘What does a cat like to do in the bathroom?’

‘As in …?’ This was Mark Ramsden.

‘As in: besides the obvious.’

‘What else is there to do?’ asked Don Drinkwater.

‘What are the options?’ said Les Cundy.

‘I want you to give me options,’ said Dan. ‘Throw something at me.’

‘Dig?’ offered Jack Meanwell.

Dan Coleman got as far as the upstroke of the d then recapped his marker pen: no, digging was a related activity.

‘Bury?’ And this – this was Bob Buchanan.

Dan’s head shook vigorously. Had Bob even been listening?

‘Think laterally,’ he said, rejoining us at the table. ‘Laterally.’

Dan explained that he wasn’t talking about what cats really did, he was talking about what their owners could be persuaded to think possible. His eagerness to distance himself from the basic function of the litter tray was a hallmark of his first days in office. Despite the seniority of his position, he was palpably ashamed of the nature of our business: not a little mortified by the staple product that had served us well for more than forty years. While it was true that we had already begun to manufacture plenty of other things under his leadership, cat litter still accounted for 70% percent of our profit. Some of us were openly nostalgic for the days when that figure had been 100%, when there was nothing but sacks of Premium Grey stacked up on the pallets in Despatch, but the monumental chastity of that enterprise had long gone, our single-product stance having given way to a plethora of sundries: scratch poles, cat flaps, play tunnels, activity towers, all sorts of injection-moulded knick-knacks. Much had been gained, I suppose, in terms of revenue and job security, but was I alone in thinking that something had been lost?

I had m anaged to remain in my job without contributing a great deal to Dan’s programme of diversification, so I surprised myself when, a few days later, I approached him in private with an answer to the question he’d put to us in that meeting. We were not on good terms, but I was due for my appraisal and needed something I could take into my PDR. That, in truth, was my sole motivation.

He seemed to like my idea:

‘Make it happen,’ he said, slapping the desk in his dismal mock-American way. ‘You have two weeks. The workshop will give you carte blanche.’

As I left his office, I noticed that the certificates, the many industry awards we’d garnered during Fred’s long tenure, had been taken down. I also noticed that the glass case containing a sample of the very first batch of cat litter we’d ever manufactured – also installed by Fred Teesdale, four decades ago, long before I joined the company – was now covered with a sheet. I wondered whether the display was still intact: the bags of Premium Grey arranged in a pyramid; the black and white photo of Fred in a warehouse coat, flanked by his Brylcreemed staff; the brass plaque on its miniature easel bearing the company motto ‘Do What You Do Do Well’; the silver cup from the European Guild of Cat Litter Manufacturers that we won three times in the mid-1970s. As I went towards the door I lifted the corner of the sheet, but Dan Coleman intervened:

‘I think we’re done here,’ he snapped, ‘I think we’re through.’

This was odd. If he was so bothered by the lowly status of our staple product, why had he given up his position with a leading office supplies manufacturer to come and work for us? His defection from that sanitary world bordered on the neurotic.

A fortnight later, we presented our designs. For it turned out that I was not the only candidate, Mark Ramsden and Bob Buchanan also having thrown their hats into the ring. When Dan Coleman had given me ‘carte blanche’, I’d assumed that mine would be the only project under discussion, but it was not the case.

There was nothing from Mick Leadbetter, Jack Meanwell, Les Cundy or Don Drinkwater, and Bob Buchanan’s pitch fell apart quicker than a circus clown’s automobile, leaving myself and Mark Ramsden in a face-off. We’d both elected to work with the hooded model, the litter tray that comes with a detachable roof. I’d had someone in the workshop cut a hole into the end of an existing litter tray, opposite the entrance flap. Then I’d gaffered a second tray onto the back of the first, filling the first with litter and leaving the second empty. There was also a join of cardboard between them, a walkway of sorts that I’d had to improvise to cover up the gap, the curved walls of the two facing lids not being flush. I hadn’t factored this into my calculations – hence the makeshift solution. It was all a bit last-minute, and it didn’t help that I was late for the presentations. Ideally, I would have got there early and thrown a sheet over it. Whenever possible, it is always better to unveil things. The unveiler is always granted a five-second window of positivity, is he not, regardless of what he unveils?

As it was, I shuffled in halfway through Bob’s meltdown, the object naked under my arm.

‘I thought you’d do it like that,’ said Mark Ramsden, as I placed it on the table.

‘Do what like what?’

‘The annexe.’ He nodded at my assemblage. ‘You’ve stuck an annexe on. So have I. Look.’

Ramsden hit the space bar on his laptop, and there was his design on the projection screen. He hit another key and we had a cat’s view of the interior. Like me, he’d got the technicians to help him, but hadn’t made the mistake of physically manifesting his idea; he’d done it all on computer, producing a slick animation that took you through the first litter tray and on into the second, which in Ramsden’s version was placed on the left-hand side. As well as being aesthetically more radical than my end-on solution, this also had technical advantages. With my design we would’ve had to recalibrate our machinery, buy in new parts, but with Ramsden’s no changes were necessary. Note, also, how Ramsden used my entrance as a springboard for his presentation, gaining rhetorical momentum directly from the inertia of my own failure – precisely what I would have done in his position.

It was a classic case of ‘after the lord mayor’s show’ when it came to my pitch, but Dan was surprisingly upbeat, nodding and laughing all the way through. I had provided the counter-example, said our line manager, the option that needed ruling out. Despite its obvious shortcomings, my design had played its part, the cardboard walkway alerting us to the drawback of an end-on solution. Good feedback, on the face of it. And I achieved my main objective: I had something I could take into my PDR.

I later learned the whole thing was a sham. The only reason Dan Coleman set us this challenge was to provide him with something he could take into his PDR. This accounted for the hurriedness of the whole affair, the kneejerk meeting he’d called at the beginning of PDR month. A few weeks later, I found out that Mark Ramsden had already tabled his design in private with Dan Coleman before the day of the pitch. In other words, he let Bob Buchanan and I toil over our offerings for no other reason than to cement his own position with senior management. Our respective travesties, in conjunction with Ramsden’s sexier submission, were evidence of the competitive spirit he fostered among his team. But it was total fiction, a story cooked up after the fact.

I can’t complain. I got through my own PDR with no probationary measures. There was no beef between me and Ramsden. Had Dan come to me instead, I would’ve had no compunction about keeping Ramsden in the dark. Like I say, in many ways we are similar. As for Ramsden’s design, it is still manufactured to this day. Quite what the cat’s supposed to do in the annexe – Ramsden’s animation was so slick no one thought to ask. Whatever, there are now trays with annexes, or ‘Powder Rooms’, as our marketing men prefer. Whether that’s a good or bad thing, I don’t know, but they are out there, alongside all the other paraphernalia. For better or worse, more world has been added to the world.

3

It was difficult to pinpoint the precise moment when I noticed something different about my journey. I’d been making this commute for a decade now and was sensitive to any deviation from the norm, so when, after ten minutes, we failed to pull in to our first scheduled stop, I assumed the timetable had changed. When the second stop was also missed, I looked out on unfamiliar terrain, the buildings sparser than usual, the arable fields replaced by common land strewn with dead silver birch trees. In the distance was … nothing. No gentle moors disappearing in mist, no cooling towers up ahead on the horizon, none of the usual landmarks. The horizon was not visible at all; the track, usually raised up over the marshland that began just after the suburbs, was instead following a cutting that only allowed you to see fifty metres or so either side. I did not recognise anything. There could be no doubt about it, I was on the wrong train.

I had to be: the sun was breaking over the left-hand side of the track when it should have been on our right at this time of the year. We were on a branch line, peeling away in a gentle south-easterly curve that had continued, it seemed to me, ever since we’d left the station. I checked the reservation stub on the seat in front to see where we were headed, but it was blank. I scanned the carriage again for Mark Ramsden. At least we were both on the wrong train. And by the way, what were the chances of that, two experienced commuters like us? Occasionally there was a late platform alteration, but I remembered checking before boarding. Tempting though it was to go automatically to the platform from which the 8:08 usually departed, I always checked the screen, because the one day you didn’t, that would be the day it left from another platform.

I didn’t see how I could have made this error. That I had followed due procedure, doing everything I normally do, everything a passenger needs to do to put himself on the right train, bothered me more than the fact of my being on the wrong one, and I took a few minutes to compose myself before trying to find my colleague. I was known for my calmness at work, a meticulous deception on my part, and I didn’t want to spoil that illusion by making an exhibition of myself in front of Mark Ramsden. But where was Ramsden? Making his way to the buffet car, as yet unaware of our predicament? Or had he stepped out onto the platform before we left, realising his error at the last moment without bothering to alert me? He’d taken his bag into the vestibule when he’d answered that call, and I was sure I hadn’t seen him return to his seat.

I reviewed my options. If I could get off at the next stop, I could catch a connecting train from there or go back and get the 09:08 service. The worse case scenario was the 10:08, which would get me to work around 12:30, and even if I took the 11:08 I’d still be there to greet our German clients and lead the tour of the facilities. But would there be any trains going back the other way? We’d been on a single-track branch line for a while now, and it stood to reason that no trains could come from the opposite direction till we vacated it. Clearly, I needed to find the Guard. He usually began the journey in a small office at the front, just beyond First Class, where he made his preliminary announcements and prepared for his routine ticket inspection, so I decided to take a stroll downtrain and intercept him on the way.

Coach C was sparsely populated, and when I asked where we were going no one responded. Now this sometimes happens when you direct a question at everyone, especially in England, so I did not find the silence of the passengers all that strange, to be honest. Neither did I find it odd when I bent down and directed the question at a woman in a rain mac sitting just by the door, and she shrugged and smiled, shaking her head quickly in the way people do when they don’t speak your language. Even when I asked a young student on the other side of the aisle, and he didn’t respond either, this was fair enough; I could see he was in the middle of some difficult calculation, a ring binder open across his lap, the pages full of equations and complicated-looking flow-charts. I apologised for disturbing him and continued through the carriage.

‘Excuse me,’ I said to an elderly lady at the far end; but before I could complete my sentence she disappeared into the vestibule, locking herself in the toilet.

‘Excuse me,’ I repeated, turning to the woman on the other side. But I was already talking to an empty seat. She too had just got up, scampering down the aisle to the rear of the carriage while my back was turned.

In Coach D I approached a man at a table, sliding in opposite and confronting him directly. Possibly I was a bit short with him. And he was busy, flicking through documents in his briefcase with one hand while scrolling down a page on his laptop with the other, a half-eaten pain au chocolat balanced on the edge of the keyboard. On reflection, he was the worst person to ask for he was already doing three things at once.

‘Where’s this train going?’ I nevertheless demanded, angered now by my failure to obtain this basic piece of information. But he didn’t seem to hear. When I repeated the question, he simply reached for his pain au chocolat, nibbled at the corner, and set it down again on the edge of his laptop, continuing to ignore me.

It was the same in the rest of the carriage: everyone looked straight through me. There were still no announcements from the Guard, no information about our scheduled stops or final destination, no reminders to keep one’s personal possessions beside one at all times, none of the usual stuff.

I proceeded on to Coach E, usually one of the busier coaches, but this morning there were nothing but bald men in suits hunched over laptops, each at his own separate table seat, not a single one of whom stirred as I put the question. I had no joy in Coach F either. The heating had failed here and it was deserted, the only occupant a young man in a blue shell suit with red hair and a silver crucifix dangling from his ear, who scowled at me as I passed, sipping from a tin of cider. I checked the reservation stubs, but again they were blank.

Coach G was packed, probably due to the fault with the heating in the previous coach, and the atmosphere seemed friendlier here, so I stopped in the middle of the aisle and made a formal announcement, a plea I suppose you’d call it, addressing the passengers as one:

‘Excuse me,’ I said, ‘I’m sorry to bother you but …’

I stopped, realising that this was just how the homeless guy begins his spiel before holding out the paper cup, and I sensed the passengers stiffening in their seats, just waiting for me to leave. Better to single someone out. I chose the fat gentleman in the green mohair suit with a carnation in the buttonhole and a bright yellow bowtie. His outfit suggested a certain approachability, but he dismissed me with a ruffle of his newspaper, so I turned to the woman in the headscarf behind him who was knitting. I felt sure she’d respond, but she cursed me for making her drop a stitch, even though it happened a split-second before and I wasn’t really to blame.

Finally, I approached the man in the wheelchair at the front end of the carriage. I was relieved to see it was the same man I saw every day on the 8:08, and I was certain he’d put me at my ease, inform me that we were simply going via a different route. I regarded him as one of the stalwarts of the 8:08 service. Usually he smiled whenever I passed him on my way to the buffet car. He smiled at everyone, as well he might, for he had a special area of the train all to himself the size of a small studio flat. We’d never actually exchanged words before, but there was an unspoken solidarity, an understanding of sorts, built up over years of eye contact. This morning, however, he was silent in a more morose way as I came alongside, shoulders hunched, head bowed, hands steepled on his lap. He looked like he was praying. At least the other two had acknowledged me, but the man in the wheelchair seemed unaware of my presence, screwing his eyes shut when I put the question and murmuring under his breath.

It was time to put a stop to this. I stood, turned round, addressing the whole carriage once more:

‘Look,’ I shouted, in a voice I hardly recognised as my own, ‘won’t someone help me? Where’s the Guard? Has anyone seen the Guard? Won’t someone tell me where we’re headed?’

4

To put all this in context, I should really describe a typical morning on the 8:08. Usually, about half an hour into my journey, I would rise from my place in the quiet coach at the rear of the train to visit the buffet car in the middle, located in Coach H. Now, you could wait for the trolley service to come round if you preferred, but any experienced commuter will tell you that the water dispensed from a trolley is not nearly as hot as that dispensed in the buffet car. And there was entertainment to be had, was there not, from passing through the intermediate coaches, each with its distinct atmospheric register. Coach C was regarded as an auxiliary quiet coach by some in the designated quiet coach, a refuge for those who had given up policing the behaviour of other passengers. For some reason Coach D always had a high percentage of corporate types hammering away on laptops, each commandeering an entire table seat to him or herself, a peripatetic extension of the office desk. This was in contrast to Coach E, the most eclectic carriage, full of senior citizens on day trips, backpackers, screaming kids, families on holiday, folk on their way to weddings, yacking ‘creatives’ with loud electronic devices. Coach F was characterised by a slightly sinister compliance, to my mind, everyone here berthed in their allotted seat, preferring to sit next to a stranger when there were plenty of double seats elsewhere. Coach G was full of people who had clearly sprinted for the train and just decided to stay put, thankful to have made it at all and lacking the motivation to find a better seat. And then there was Coach H, the buffet car itself, with its deafening extractor fan and humid gust of pastry aromas, marking the end of Standard Class. Just a little further was a vestibule where I sometimes liked to loiter after getting my coffee, peering through the sliding door at the First Class passengers, with their complimentary newspapers and at-seat restaurant service, for no other reason than that my ticket entitled me to do so.

This, then, was the normal order of things. But that morning everything already seemed out of tune as I took my seat in Coach B. The subsequent behaviour of the passengers – their silence when I asked them where we were going, their refusal to acknowledge me – was foreshadowed by an intuitive sense that all was not as it should be. Only a little later did I perceive its root cause, which became more noticeable the further I advanced. As I got up and passed along the aisle, several faces were well known to me from my daily commute. Naturally, the presence of these regulars didn’t strike me as odd when I believed I was on the right train. But it became very odd indeed when I realised I was on the wrong train. It took a while to realise that what was most unsettling was that we were all on the wrong train. Everyone should have been just as anxious as me, up on their feet, looking for the Guard, asking each other what was going on, but there was nothing in their faces to suggest that the scenery rushing past the window as we continued to bear south-east was anything but familiar.

After Coach G, the next vestibule should have led directly to the buffet car in Coach H, but there were no pastry aromas, no food smells of any kind, and I could see from here that there was no counter at the far end of that carriage, just further ranks of passengers canted over to one side as we continued to bear left. As I approached the door, I assumed this was a new train recently brought into service – the newer models have an extra coach before the buffet car, and the livery looked slightly different, a bluer shade of grey with a glossier finish.

It was then that I thought it might be a better idea to go back. I thought I remembered seeing the Guard at the rear of the train, just before pulling out, and it seemed more sensible to eliminate that possibility before heading to his office at the front. There was another coach right at the back, not accessible to the public, between Coach B and the rear engine, that the trolley operators sometimes went into after they’d completed their first leg of Standard. Sometimes the Guard began his routine ticket inspection from there, emerging from behind you and taking you by surprise.

When I went back into Coach G, the man in the wheelchair had moved from his special area on the left, positioning himself in the middle of the aisle. I assumed he was about to visit the disabled toilet, so I stood aside, waiting for him to go past. But he stayed where he was, head bowed, hands clasped together in that same gesture of supplication as before, the tips of his fingers going red, his forearms shaking from the pressure. He held this posture for a few seconds, then his hands parted theatrically and he came closer, forcing me towards the vestibule.

‘Excuse me,’ I said.

It was now that this hitherto jaunty commuter, for so long a talismanic presence on the 8:08, was transformed into what I must now call the Harbinger. I call him that because he seemed to mark the boundary between things as they were and things as they are now.

‘And what can I do for you?’ he asked.

I was wrong-footed by the Scottish accent – I’d always assumed he was English.

‘I need to find the Guard.’

‘The Guard?’

He was in much better shape than I remembered. His upper body development was impressive, enhanced by the lumberjack shirt he was wearing, which was cut off at the shoulders, revealing his huge biceps. His wrists were thicker than my forearms, massive trapezoids joining his neck halfway up, a tiny head that he kept low, like a ram getting ready to butt you, and a face that seemed too big for it, top lip curling up over his teeth, which were whiter, much whiter than I remembered. I didn’t recall him having such good teeth and such fine arms, or such a small head. Not till he became the Harbinger.

‘He needs the Guard,’ he shouted over his shoulder. ‘He’s asking about the Guard. Has anyone seen the Guard?’

There was a howl of laughter from the whole of Coach G.

‘No Guard hereabouts,’ said the Harbinger. ‘Not for a while now.’

‘But I saw him,’ I said. ‘I saw him at the back.’

‘The back? He says he saw him at the back.’

More laughter.

‘Yes. Near Coach B.’

‘Coach B?’ The Harbinger grinned, his huge hands caressing his wheels, fingernails running along the treads of the tyres. ‘B, you say? Which one?’

‘What do mean which one?’

‘Which B?’

‘Coach B.’

‘Yes, but which Coach B are you talking about?’

‘I don’t understand.’

‘Let me put it this way.’ The Harbinger rolled closer, pinning my shoe under his wheel, pressing me against the vestibule door, which slid open, leaving me on the threshold. ‘How many coaches did you come through? Just now?’

I counted them on my fingers: ‘B, C, D, E, F, and this one, G.’

‘Six coaches? That’s all? And you say you saw the Guard?’

‘I think so.’

‘You think so. He thinks so. Tell me, which direction was he going in?’

‘This way, I assume.’

The passengers were whispering now, some of them pointing to their temples, making ‘mad-person’ gestures to each other.

‘Quiet!’ yelled the Harbinger. ‘There must be some mistake, some personal oversight on your part. The Guard has never been seen in these parts.’

‘What do you mean, these parts? I saw him at the rear of the train.’

There was further laughter here, more muted than before. ‘No Guard hereabouts,’ said the Harbinger. ‘Hereabouts or thereabouts.’

‘Hereabouts or thereabouts,’ murmured the other passengers moronically, ‘hereabouts or thereabouts.’

‘Look, I need to get back to my seat.’

‘Inadvisable,’ said the Harbinger.

‘Let me past.’

‘I strongly advise against it at this time.’

‘Let me through. My stuff’s there.’

‘Your what?’

‘His stuff!’ It was a child’s voice, coming from the rear of the carriage.

A thin man in tweed with a greasy comb-over got up from a table seat, and the boy handed him a bag: my overnight bag.

‘There you go, sir,’ he said, when he’d come back up to our end of the carriage. ‘I’m afraid we had to look inside to establish the identity of the owner. Oh, and this is yours too, I believe.’ He handed me a ticket.

‘I already have a ticket.’

‘With respect, sir, I think it’s yours.’

I checked my pockets. There was nothing there.

‘Thanks. Thank you.’

‘No problem, sir. We found it in your wallet.’

‘My wallet?’

He was already handing it to me. Then he bowed and returned to his seat.

‘Hang on a minute. My jacket. What about my jacket?’

Here it came, passed up the carriage by the other passengers, the arms dragging over the tops of the seats like the wings of a dead bird.

‘There,’ said the Harbinger. ‘You have all you need. And now you must go.’ I thought he was going to shake my hand as he leaned forward and caught hold of my wrist, but he gave me a massive Chinese burn and pushed me in the chest as hard as he could, sending me flying into the vestibule. ‘Go!’ he repeated, as the door slid shut. ‘Go, and do not come back!’

Have you ever walked into a patio door you thought was open? Or thrown your whisky onto the backgammon board when you meant to reach for the dice shaker? Or stood in a bar and stared at your dead father for ages before realising the far wall is mirrored, the bar half as big as you’d thought, your face no longer as young as you’d imagined? Or fallen ill on holiday and asked a local to direct you to a doctor, and he has pointed to a plausible facade in a side street, with a clean reception staffed by refreshingly informal women, where you have waited for five minutes before realising it’s a brothel?