Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Banipal Books

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

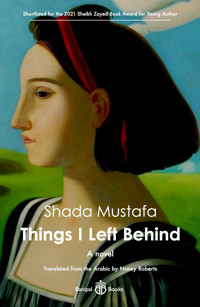

Shada Mustafa is a Palestinian writer, born in 1995. She graduated from the Faculty of Architecture at the American University of Beirut (AUB), and is currently pursuing a Master's degree in Geographical Development Studies at the Free University of Berlin. Her debut novel Ma Taraktu Khalfi (Things I left Behind) was shortlisted for the 2021 Sheikh Zayed Book Award in the category of Young Author. It was excerpted in Banipal 71 (Summer 2021), translated by Nancy Roberts.Nancy Roberts is an award-winning translator of novels by contemporary Arab authors, including Ghada Samman, Salwa Bakr, Ibrahim Nasrallah, Laila Aljohani, and Ahlem Mosteghanemi. Her most recent translation is The Slave Yards by Najwa Bin Shatwan, Syracuse University Press, 2020, while her translation of Ibrahim Nasrallah's Gaza Weddings shared the 2018 Sheikh Hamad Award for translation.Shada Mustafa is a Palestinian writer, born in 1995. She graduated from the Faculty of Architecture at the American University of Beirut (AUB), and is currently pursuing a Master's degree in Geographical Development Studies at the Free University of Berlin. Her debut novel Ma Taraktu Khalfi (Things I left Behind) was shortlisted for the 2021 Sheikh Zayed Book Award in the category of Young Author. It was excerpted in Banipal 71 (Summer 2021), translated by Nancy Roberts.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 157

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Shada Mustafa

Things I Left Behind

Shortlisted for the2021 Sheikh Zayed Book Award for Young Author

Things I Left Behind

First published in English translation

by Banipal Books, London, 2022

Arabic copyright © Shada Mustafa

English translation copyright © Nancy Roberts, 2022

Ma Taraktu Khalfi was first published in Arabic in 2020

Original title:

Published by Naufal Books, Beirut, Lebanon, 2020

The moral right of Shada Mustafa to be identified as the author this work and Nancy Roberts as the translator of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988.

No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher

A CIP record for this book is available in the British Library

ISBN 978-1-913043-26-1

E-book: ISBN: 978-1-913043-27-8

Front cover painting “The Field” by Afifa Aleiby

Banipal Books

1 Gough Square, LONDON EC4A 3DE, UK

www.banipal.co.uk/banipalbooks/

Banipal Books is an imprint of Banipal PublishingTypeset in Cardo

Printed and bound in Great Britain by Clays Ltd, Elcograf S.p.A.

Special thanks to my professor,the novelist Rachid al-Daif

To my mom, and to my three former “homes”

I don’t drink milk. Everybody used to think I was too young to understand what was going on. I started believing that after a while. I was supposed to live with my dad. I didn’t know why. I didn’t want to know. Before I went to live with him, I liked milk. When my mom prepared it, I’d always ask for more. But my grandma, after my parents’ divorce, didn’t know how to prepare it the right way. After a bout of stubbornness every morning, my dad would have to force it down my throat. To this day I can’t stand the taste of milk.

***

My mom lived in Ramallah, and my dad in Jerusalem. I was six years old as I recall. My brother was five and my sister was eight. Every weekend we’d pack our clothes in a suitcase and go visit my mom. We’d go from one place to another, one address to another. My dad would take us to the checkpoint between the two cities. We’d cross by ourselves and wait for my mom on the other side. The suitcase was bigger than we were. The looks people gave us were bigger than we were. As I walked along, I’d wonder: Why do we have to carry this suitcase?

1

My mom lived with my grandparents in Ramallah. When we went on our weekly visit, they would always ask us what we wanted to eat, and we’d ask for macaroni. My cousin would get mad because we always asked for the same thing, and because we were depriving him of the chance to eat other dishes on the day he came to visit his grandparents. He’d make other suggestions to get us to change our minds, but we wouldn’t do it. We’d come to see our mom, and we wanted macaroni! We wanted there to be at least one constant in our lives.

2

We lived for two years with our dad in Jerusalem. During those two years, our stepmom used to sing us songs before we went to sleep. She’d read us stories and play with us. Maybe she loved us. But one time my sister said to me: “Do you remember when we went to live with our mom? It was when our little brother was born.” I didn’t know who to believe: myself or my sister.

2

After we went to live with my mom, my dad would call every other day to check up on us, and we would go visit him every week. After a while, the phone calls and visits grew less frequent. We would only hear his voice when we called him, since he didn’t take the initiative to call us. The weekly visits became monthly, then bimonthly, and finally, I only saw him once a year. I didn’t know how or why all this happened.

2

Sometimes I wonder how the Palestinian cause relates to individual people’s lives or the life of a family. Where does it fall on the scale? Which carries greater weight? The person, or the cause? I want to care about the cause, but I can’t. All I can think about when somebody talks about the Palestinian cause is the fact that it stole my dad from me. I keep going back in time and thinking: If he hadn’t gone to prison, would he and my mom have gotten divorced? Would I be able to look at my dad now and not find mountains between us? If it weren’t for the cause, might I have a father I loved, and who loved me? Would I have a happy family? And then I think: Which is more important? The human being, or the cause?

2

I don’t remember the period my dad spent in the occupier’s prison. I think I was only three years old when he left. All I remember is what I was told, or rather, what my mom told me. My dad had gone to prison and spent a year and half there. Then he got out, but he didn’t get out. She used to say he’d become a different person. He’d changed completely, and she couldn’t live with him anymore. He’d become the person we know today. I never knew my dad in his previous persona, his good persona. I never knew him.

2

I was six years old and it was the first day of the new school year when, to our surprise, our dad took us to a new school. That was in 2000, the year the al-Aqsa Intifada1 began. My old school had been in Ramallah. Every day we would go from Jerusalem to Ramallah to get there. At that time there was no checkpoint between the two cities, so it was easy to get back and forth between them. The trip only took half an hour. That was before the Intifada. That was before the divorce. After it, my mom moved to Ramallah, and we stayed with my dad in Jerusalem. We also started going to school in Jerusalem. And the barrier that separated my mom and dad – the Qalandia Checkpoint – went up.

1 Also known as the Second Intifada (September 8, 2000 to February 8, 2005), it is commonly referred to as al-Aqsa Intifada due to the fact that it broke out at al-Aqsa Mosque in Jerusalem.

1

There are a lot of things about that time period that I don’t remember. But I remember well the checkpoint between Ramallah and Jerusalem. It consisted of barbed wire, big cement blocks, and rifle-carrying soldiers. It was quite simple, the barrier that kept me from seeing my mom. It was the first Mother’s Day since the divorce. All three of us pressed my dad to take us to Ramallah. We wanted to be with our mom on this day. We bought presents for her and went to the checkpoint, thinking we’d get to see her. But all we saw was gunfire, clashes, and an uprising. We couldn’t pass through. We couldn’t cross the checkpoint to be with our mother on Mother’s Day.

1

The checkpoint was closed the next morning too, but we kept pressing my dad, saying: “We want to get through!” So he asked a soldier to let us cross over so that we could see our mother on the other side. The soldier just said: “Get out of here before I beat you in front of your kids.” My dad came back and explained what had happened. I was seven years old. At the time, I didn’t hate the occupation because of that sort of humiliation. I didn’t hate it because of the people who’d been killed, imprisoned or tortured. I didn’t hate it because of the tanks or the curfews or the demolitions of people’s homes, or even because of the checkpoint. The only reason I hated it was that it kept me away from my mom. I just wanted to see my mom.

1

For two years after that, we’d cross that checkpoint to see our mom once a week. I didn’t always hate the soldiers. There were times when I felt friendly toward them. One day when the checkpoint was closed, we asked a soldier to let us cross over. Seeing that we were just three little kids, he moved the barbed wire to let us through. I was ecstatic. I didn’t care about the line of people who were still stranded on the other side. I’d crossed over and I was going to see my mom. The soldier had let me see my mom.

2

I grew up passing through that checkpoint. Even after we went to live with our mom, we’d cross it to go see our dad. The checkpoint grew with me. It evolved from a barbed-wire fence in the dirt into a building containing scanning equipment like they have at border crossings and in airports. I remember that checkpoint well. I remember it well, since my dad never gave us a chance to forget it.

2

That was before we moved to my mom’s house. It was summertime, and I was about to go outside and play with the neighbor kids, when all of a sudden I found my mom standing in front of me. She told me to call my brother and sister and quickly get into a car that was waiting for us outside. As we got in, I was still tying my shoelaces. Then the car stopped. I looked up to find my dad standing in front of it. We weren’t able to leave. I wanted to go be with my mom, but I couldn’t. My dad sat us down after that and started scolding us for getting into that car. He reminded us that he took us to see Mom every weekend. He said he always went through a terrible hassle on account of the checkpoint, and that there was no justification for getting into that car.

You knew we wanted to go with her, that we wanted to stay with her. So why didn’t you let us? Why did you have to make us feel guilty for wanting what we wanted?

2

When I was seven years old, I remember sitting with my dad’s family: my grandma, my grandpa and my paternal uncle. My dad has two younger brothers, but my other uncle on his side wasn’t there. Noticing that, unlike usual, I was sitting there not saying a word, my uncle asked me what was wrong. I didn’t answer. So he asked my dad, who told him that I wanted to go to Ramallah. My brother and sister had gone to visit my mom the day before. I’d been sick at the time and hadn’t been able to go. But now I was better and I wanted to be with my mom. My dad said: “She wants me to go through the hassle of driving to the checkpoint and getting caught in traffic so that she can have a good time.” I was about to cry. So my uncle took me instead. My uncle was so kindhearted, there were lots of times when I wished he was my dad.

1

When we first moved to Ramallah, we lived with our mom at my grandparents’ house. One of us would sleep next to her, and the other two would sleep in another room. After a while, we moved into the apartment on the first floor of their building. That was our old house. We’d lived there for ten years, and I always felt homesick for it. My mom didn’t like that house. She said it felt like a storage shed. It was small, and the sitting room was dark. But I liked it. The house was surrounded by a garden that my grandma took care of, and I used to wake up to the sight of the lemon tree next to the window of my room. The fig tree my grandma loved was outside the kitchen window. My mom used to complain about the kitchen, since it was cramped, and if everybody sat at the table there, it was hard to move around. But I liked it. I also liked my mom’s room, especially its colors. It had pretty red-and-white curtains. But we weren’t allowed to go into her room. It belonged just to my mom. It was the only thing, the only place we couldn’t share with her.

1

My mom used to wake up every day to fix breakfast for us and take us to school. Then she’d come home and get ready for work. During her lunch break, she would pick us up and bring us home, and we’d sit around the table for the lunch she’d prepared the night before. Then she’d go back to work. In the evening she’d come home, prepare food for the next day, clean the house and rest for an hour, then go to bed. I used to eat that breakfast and that lunch, sit at that table, and go to school and come back in that car without knowing, without feeling for her. I was a kid. But I wasn’t a kid. I could have seen, but I didn’t. I chose to ignore what was there. I chose to ignore her situation. I chose to ignore everything that was happening, everything that had happened. And now I wonder: What was she feeling? Did she feel that her children were her prison? Did she wish she could leave? Was it her love for us and her sense of obligation toward us that made her stick around? Or was it the knowledge that if she didn’t, she was bound to feel guilty? I don’t know. All I know is that whenever I look back, I see a prison that was created for her, or one we created for her.

1

My mom wasn’t religious at all. But during a certain period when we were little, we would see her perform the ritual prayers. That was when I was eight or nine years old. She would put on prayer clothes and go to her room. When I saw her do that, I was surprised. Why the sudden attention to religion? Didn’t she find anything to console her on Earth? Why was she praying? Who was she praying to?

1

My mom also went through a phase of being super irritable. When I say a phase, I mean from the time I was six till I was around twelve. If we fought, she’d get mad. If we dropped something, she’d get mad. If we broke something, she’d get mad. If we hurt ourselves, she’d get mad. If we fell while we were playing, she’d get mad. If we didn’t understand something, she’d get mad. If we talked at the wrong time, she’d get mad. We spent six years seeing her get mad.

1

When I was little, I’d feel scared when my mom got mad. She’d yell really loud, and if we were in the car, she’d floor the gas pedal and we’d go flying. I’d be petrified when that happened. When she saw me like that, she’d tell me not to be scared. She’d get mad easily, but she’d calm down right away. When I remember all this, I think: Who was she so mad at? At him, or at us?

1

I used to get mad at my brother and sister if they did something that upset my mom. I used to think: Why don’t they just avoid trouble? Why don’t they think? All that mattered to me when I was little was not to upset her, and to avoid her anger and her shouting. So when my brother and sister did something that upset her, I’d get angry with them. Everybody was always getting mad at everybody else and blaming everybody else. But I think our aim was to please her, or even to get close to her. She was the most important thing. She was always the most important thing. At lunchtime, we’d fight over who got to sit next to her. When it was her birthday, we’d go out with my grandma and grandpa and buy whatever presents we could for her. We’d make her a cake and surprise her. We never did things like this for each other. We didn’t care about each other. We only cared about her. We wanted to see her happy. But I don’t remember her being happy about any of this. I used to get the feeling that it bothered her when we surprised her on her birthday and when we tried to express our love for her. Was our love a burden to her?

1

Sometimes my mom would be late getting home to us after work. She worked at a bank in Ramallah, and instead of coming straight home, she’d go for a walk. Sometimes she’d be gone for half an hour, and sometimes for an hour or more. We would wait, and when she got back, we’d receive her at the door, excited – or maybe relieved – that she’d come home, that she hadn’t decided to leave us. She’d come into the house and go to her room to change her clothes. Then she’d come out and start making sure everything was all right: that the house was clean, that there weren’t any dirty dishes in the sink, and that we’d done our homework. Then she’d help any of us that needed help. I wasn’t a top student. There were lots of things I didn’t understand. I didn’t want to understand. When my mom went to the parent-teacher meetings, she’d hear all sorts of praise for my brother and sister. But about me, all she’d hear was: “She needs to work harder. She needs to study more.” There were lots of times when I felt she was ashamed of me. But I couldn’t do anything.

I didn’t know how to please you, Mama.

1

My mom used to insist that we be on our best behavior at all times and places. We had to eat right, drink right, talk right, dress right, and not play too far from the house. When she saw our clothes looking the worse for wear after we got back from Jerusalem, she’d blow her top. When we were in Jerusalem, we’d spend most of our time playing in the street. Nobody there much cared about our appearance or anything like that. So, to keep my mom from getting angry, we hit on the solution of dividing our clothes into two sets: our Jerusalem clothes, which were scruffy and old, and our Ramallah clothes, which were spiffy and new. The way we behaved depended on what we were wearing and where we were. So those two sets of clothes created two different worlds for us, and we were caught somewhere in the middle.