Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Parthian Books

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

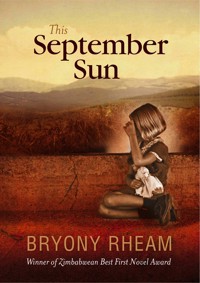

Winner of Best First Book Award at Zimbabwe International Book Fair 2010. Ellie is a shy girl growing up in post-Independence Zimbabwe, longing for escape from the confines of small-town life. When she eventually moves to Britain, her wish seems to have come true. But life there is not all she imagined. And when her grandmother Evelyn is brutally murdered, a set of diaries are uncovered spilling out family secrets and recounting a young Evelyn's passionate and dangerous affair with a powerful married man. In the light of new discoveries, Ellie begins to re-evaluate her relationship with her grandmother, and must face up to some truths about herself in the process. Set against the backdrop of a country in change, Ellie burdened by the memories and the misunderstandings of the past must also find a way to move forward in her own romantic endeavors.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 639

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2013

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

This September Sun

Bryony Rheam

In memory of my grandmother, Beryl Beynon Gillen, who enjoyed a good story and a strong cup of tea.

And for John with lots of love, always.

Contents

Title Page

Dedication

Part One

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

Chapter Nineteen

Chapter Twenty

Chapter Twenty-one

Chapter Twenty-two

Chapter Twenty-three

Part Two

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

Chapter Nineteen

Chapter Twenty

Chapter Twenty-one

Chapter Twenty-two

Chapter Twenty-three

Chapter Twenty-four

Part Three

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Extracts

Acknowledgements

About the Author

Copyright

Part One

Chapter One

On the 18th of April 1980, my grandfather burnt the British flag. I remember because it was my sixth birthday and he ruined it. My mother had made me a cake: it was in the shape of a heart, a big brown chocolate heart with white pearls of icing strung along the edge and ‘Happy Birthday’ written unsteadily across the middle. Gran had iced it, but she was feeling the effects of trying to give up smoking and her hand had wavered over the ‘a’ of ‘happy’ so it looked like an ‘i’. ‘Hippy Birthday,’ Dad joked as he lit the candles. ‘Hip, hip hooray.’ Then Mom noticed that Grandad wasn’t there, so the candles were blown out and Gran went to look for him.

Inside the house, my grandmother’s lunch lay in the dustbin. It was beef stew with green beans and mashed potato. We had eaten lunch in silence. Dad read the newspaper that lay on the table. Mom hated that. She said it was rude: it ‘cut off communication’ were the words she used. Today she just looked down and ate. Her knife and fork occasionally scraped the plate, the only noise at the table. If I did that, I was told to eat properly and quietly, but grown-ups are always allowed to break the rules. Gran sat and looked at her food, pushing it round and round her plate. Mom eventually got up and cleared the table. Without a word, she took Gran’s plate to the kitchen and emptied it into the bin. Grandad wasn’t there. He was ‘at the club’. That meant he was drinking.

The day of my sixth birthday was the day Zimbabwe got its Independence from Britain. No one went to work. Prince Charles came all the way from England to shake Mr Mugabe’s hand and give back the country to the black people. Many white people had already decided to leave by the time the Rhodesian flag was lowered and the new Zimbabwean one hoisted. Grandad said we were in for trouble; this was just the beginning. That morning he disappeared, but returned in the late afternoon as Gran was making tea and putting the cups and saucers on a tray. I was in the small room that adjoined the kitchen and acted as a pantry, looking for the candles to put on my cake. I heard them argue as Grandad had been drinking and was leaning against the wall for support. Then Gran called me and we went outside onto the verandah as we always did around about four o’clock. Afternoons tended to have a pattern back then.

By the time we noticed my grandfather was missing from the circle around my cake, he had lit the stolen Union Jack and came running out in front of us, spinning furiously round and round in circles with it. He was turning so fast that the flames looked like a giant Catherine wheel, a great golden loop of fire. Then he let out a long deep mournful cry of sorrow that sounded like the very call of death and sent a chill through us all. I can see us standing there around the table, frozen as if by a sudden icy wind, the late afternoon sun retreating like a war-weary warrior trudging homewards, defeated. I can see my mother turn and rush inside the house to get water, my father speechless and still; I can feel my nails as I dug them into my palms in fright and then I see my grandmother run out of the house and over to our macabre entertainer, screaming at him, her voice like hot oil, hissing and spitting and boiling, ‘I hate you! I hate you!’ As she reached him, he threw back the burning flag and it fell on to her, the flames reaching out like fingers to catch hold of her skin. She stumbled back onto the grass.

What happened next is a blur. I cannot remember who helped her and what was said, what my grandfather did or what was done to him. All I know is that was how she got the scar on the underside of her forearm. It was dark and ugly and, as she grew older and her skin sagged, it reminded me of old tea. Unusually enough, it was in the shape of a teapot. I said that it looked like the shape of Zimbabwe etched on her arm. I think Gran was always a little proud of the mark, a symbol of the price she paid for freedom. Many years later, the man who murdered my grandmother would remember that mark as the last thing he saw as she raised her arms against him before he brought the butt of his gun down on her head.

Chapter Two

Smile though your heart is breaking

Smile even though it’s aching

Where do you start to put a life together? The pieces don’t always fit. Many are missing, or borrowed. From other people’s lives, other people’s memories. Their own puzzles. Where is the beginning when you have only the end to start with? How many lies are told over the course of one lifetime? What of all that is not said, merely meant, hinted at, subsiding beneath the surface of action and words? All that is yearned for and never had?

*

My grandparents separated soon after my grandmother recovered, at least physically, from the flag burning incident. Gran moved out despite much pleading from my mother, tears from me, and my grandfather’s sorry silence. She got a job in the accounts department of Haddon and Sly and rented a small flat on Wilson Street. I don’t think any of us realised how difficult it was for her, leaving her old life behind, especially in the face of such adversity. There was no one she could talk to; Mom couldn’t see her point of view, couldn’t understand why her mother, at her age, had to stop living with us and start out on her own. That my grandparents hadn’t got on for years was no secret in our family, but my mother had never let that leak to the outside world. It was a long time before she acknowledged Gran’s departure, if she ever did. Everything Gran did was judged within the context of her leaving us and setting up her own home.

In the days before she moved out, when her things lay packed in two suitcases and a large cardboard box, I cried every night as I lay in bed and, when I woke, my eyes were swollen and sore to open. Alone in the afternoons, I peered round Gran’s bedroom door and looked resentfully at her half-packed things. The space she left echoed noisily when she had gone and we all stumbled clumsily around the house, not knowing what to do and what to say and everything sounded false and far too bright and cheery. We were like the Colgate advert, where a gleam twinkles off the man’s happy white smile. ‘He must use bicarb on them,’ said Mom, when she first saw it, because everyone knows that brilliant white teeth aren’t natural.

The routine that I had known was rudely disrupted. When she lived with us, Gran would often walk me home from school. Grandad and Dad would come back from work at one o’clock and have lunch. Sometimes Grandad had a nap, but Dad never did. He read the paper and drank tea and talked to Mom. Then at a quarter to two he would get in the car and drive back to work, dropping Grandad off at Fox’s on the way.

Grandad was a mechanic. He wore blue overalls to work that were always greasy and he always smelled of oil, even after he had washed. In fact, even after he retired and lost all interest in fixing broken carburettors and cracked radiators, a thick smell of oil seemed to emanate from him at times, as though all the years of working at Fox’s garage had ingrained themselves under his skin.

After lunch, my Gran would go for a rest for an hour or so and Mom would be in the kitchen sorting out dinner or making a cake or scones. The house would be very quiet. At three o’clock Gran would emerge from her room, mumbling about the heat and how much there still was to be done in the house. If I were bored I would sit outside her room and listen for the creak of the bed, which meant she was getting up. Hours passed slowly and often it seemed as though the afternoon would stretch on forever before that one silent hour would be over.

The hour before Dad returned from work was spent with my grandmother. Sometimes we would walk to the library together, my books to return in a bag in one hand, the other holding Gran’s. She also listened to me read and would sign my reading card afterwards so my teacher knew I had done my homework.

At night she would read to me from one of my library books, mainly Enid Blyton – The Magic Faraway Tree and The Famous Five – stories of children who ran about the English countryside, finding fairies and elves, or smugglers, joining the circus or exploring the caves of Devon: so different to me in a dusty old town in Africa with snakes and mosquitoes and endless hot days and nights.

Now she was gone and the afternoons stretched empty and dreary with a longing that could not be filled. To try and make me feel better, Gran let me help her unpack in her new flat and let me choose where to put her ornaments, even if some were in slightly strange places. I placed her two silver candlesticks on the floor, either side of the table on which her television rested, and a huge pot plant on a small side table that it completely dwarfed. It was so big you expected the table to collapse at any moment.

When my mother first saw it, she moved the plant without saying a word, she was so used to arranging other people’s lives. Gran told her firmly to put it back as it was ‘fine there’, and winked at me conspiratorially. Gran didn’t have much furniture of her own as Grandad made a huge fuss over every piece she wanted to take. My mother said she wasn’t taking sides over the issue, although really she did by doing nothing. Gran had no bookcase for her collection of paperbacks and her hardback Reader’s Digest anthologies, so we piled the latter into two pillars, placed a plank of wood across them and arranged the rest of the books in a row on top.

She never spoke to me about her decision to leave or the whys and wherefores of her relationship with Grandad. In fact, no one ever spoke to me about it. Somehow I was expected to just know. When I was a bit older and watched television more, I was always amazed at American family sitcoms, where parents had heart to heart conversations with their children, conversations that always ended with each party saying how much they loved the other. I cringed to see such open shows of emotion, especially if Grandad or my parents were in the room.

My mom had told me not to tell anyone about my grandparents; if they asked I was to say it was none of their business. She was still hoping Gran would come back and the whole affair would blow over, even though Gran now had a job and seemed so much happier than when she lived with us. Mom had initially come up with a great convoluted story, which Dad had laughed at, much to Mom’s chagrin.

The story was that they were moving out into a flat. However, the flat still had to be decorated and so Gran was going to live there while she did that. She had to sleep in the lounge and there wasn’t enough room for Grandad as well. The flat would take a while to be finished, especially because Gran was so fussy about paint colours and it was hard to find good upholstery in Zimbabwe these days. I was relieved when Dad reminded Mom that I was only six years old and unlikely to remember such a story, although I was frustrated, too, that I had let her down.

In the first couple of years after Independence, both for Zimbabwe and Gran, she and I spent a lot of time together. To compensate for her absence at home, I would often stay the weekend with her. Mom or Dad would drop me off on Saturday morning and pick me up on Sunday evening. Even if I did not stay the whole weekend, I would at least spend a morning or afternoon with her.

In many ways I was the strongest link between her old life with us and her new life on her own. I was also the go-between. Gran never came to our house and Mom entered Gran’s flat uneasily. She never stayed long. Although they spoke often on the phone, there was always an extra message that I was asked to relay, either to Gran when I was dropped off, or to Mom when I was picked up. ‘Please give Gran these lemons and tell her I’ll bring some more round on Tuesday.’ ‘Tell Mom I’ll phone her on Wednesday.’ And it wasn’t just messages that I conveyed, but snippets of information about each other’s lives: what Gran made for dinner, whether she was lonely or not, how Mom got on with Grandad now that he was on his own, all the questions they couldn’t ask each other. For the most part, I answered all their questions as honestly as possible, although I was protective of both. I shielded Mom from Gran’s often acidic tongue, and Gran from Mom’s pessimism, her certain belief that Gran had done the wrong thing.

My grandmother had learned to drive when she was forty-five years old and continued for the next ten years to drive illegally, until she finally got her licence. When she lived with us there was always a fuss whenever she wanted to take Grandad’s car into town. He would shout about the insurance and ask who would pay if she had an accident or even just backed the car into a tree. Gran said that was typical – men didn’t even take women’s accidents seriously. The glory of great accidents was denied women who were left to reverse into trees and walls or run over the dog – or their husbands, she had once muttered mischievously – little accidents of no consequence that illuminated the whole character of woman: irrational, illogical, untrustworthy.

A few months after leaving us, Gran bought a car, a 1969 Toyota Crown sedan. It was blue. And big. She called it Shirley, for some reason. I forget now. Everyone knew Gran’s car. I used to look out for it when we went into town. If it was outside Downings, I knew she was buying bread: a wholemeal loaf and a stick of French bread if it was Friday, for the weekend. If it was outside the bank, I knew she was actually in the fruit and vegetable shop opposite and would be there for a while as she and Mrs Patterson, the cashier, would chat for a long time after Gran had paid. Even if the shop were busy, Mrs Patterson would carry on talking while handing other customers their change or weighing apples and potatoes, tying a knot in the neck of the plastic bags she put them in and sticking the prices on the side.

Next door was the butcher with only one arm. It was sawn off above the elbow and I always imagined that he had got it caught in his mincing machine. At other times, I half expected to see it lying amongst the cuts of meat on display, perhaps decorated with a bit of lettuce and cucumber and adorned with an orange star which said ‘Today’s Special. Arm half price!’ Gran pulled a face when I told her and said that he had lost it in some sort of accident or other years before, but it didn’t stop me thinking of the mincing machine and the noise it would have made as it chewed through the bone and flesh.

If I saw the car outside Mr Patel’s, I knew Gran was looking for material. She would choose a bolt of cloth and the assistant would carry it down for her, heave it onto the counter and measure out a metre or so. Mr Patel could tell exactly how much you needed for trousers or a skirt or dress. He would slice through the material with a big pair of black scissors and then fold it again and again into a small square. I loved the way he did it, the motion of the scissors, the way the material surrendered to the blade. I loved the sound and the speed, the way he folded the cloth and put it into a plastic bag, sealing it with a piece of Sellotape, in one smooth motion.

One day I told Gran that I wanted to work there when I grew up. She laughed. The next time we went to Mr Patel’s she told him and he grinned widely. I felt embarrassed and couldn’t understand why they thought this so funny. I didn’t like not understanding. It was at times like these that I felt an enormous gap between me and a world I didn’t, and perhaps still don’t, understand. The truth, it seems, often lies further than where you look.

I wasn’t the only one who looked out for Gran’s car. Grandad did too. Whenever he was in town, his eyes continually scanned the parking bays along the side of the road. If he did spot the great blue machine that always, due to its size, stuck out into the road, he never had a good thing to say about it. He saw dents and scratches that weren’t there. If the wheels were anywhere near over the line, he spoke of women’s inability to park, let alone drive; if Gran parked in the sun he ranted about the damage it would do to the upholstery. He checked to see if the car was clean inside and out, whether she left any rubbish in it.

Once she left a red lipstick on the front passenger seat without its top on and it melted in the sun. The liquid colour, as it became, got ingrained in the seat, which had a pattern of little grooves in the middle and down the sides. I don’t think Gran ever tried to clean the seat, so the colour stayed, giving the strange impression of blood, as if someone had been murdered sitting there.

I knew that Grandad missed Gran. I got tired of his complaining but, at the same time, I felt a knot of pain twisting itself deeper and deeper within me. I knew their separation had somehow resulted from Gran being burned that day but I couldn’t understand why she could not forgive him for that. Even before that incident though, I couldn’t remember my grandparents ever being happy together. Alone, yes, they each could be funny and laugh, but not together. Together there was always a sense of sadness and bitterness about them, as if the very air between them was eaten away, and hung, full of holes, like an old flag beaten about by the wind.

Chapter Three

There were many things my grandmother enjoyed doing. She loved going for walks in the park, but she didn’t like the bush and even somewhere like Hillside Dams was a bit too rural for her. I think she liked the order that she found in the park: the pots and the carefully trimmed flowerbeds. She liked the fact that you could sit on the lawn and that there was plenty of shade. She wasn’t one for anthills and snakes and sitting on a rock under a thorn tree. That isn’t to say that she didn’t appreciate the beauty of the bush, for she did, as long as it was from the comfort of a lush green oasis.

She also enjoyed cooking and baking, especially rich chocolate cakes and feather-light melt-in-your-mouth Victoria sponges. She was a stickler for ceremony and even the most mundane visitor was offered cake with their tea. She also made sandwiches with grated cheese fillings and slices of cucumber. She’d cut the crusts off and decorate them with shredded lettuce. Somehow they always tasted better than any other sandwich and, for a long time, I thought it was because she sliced them diagonally, rather than straight down the middle, which seemed so ordinary and plain in comparison.

I loved to watch her bake, to watch the wave of thick creamy batter turn over in the bowl as her wooden spoon ploughed under it. I loved the way it slid smoothly into the waiting greased tins, the way it baked, turning darker and firmer in the oven.

‘It’s all in the eggs,’ she would say to me, as she folded them into the flour. ‘Never scrimp on the eggs and never bang the bowl or the baking tin, or you’ll knock all the air out.’

She also told me to always use less sugar than the recipe asked for as most recipes were from South Africa or the UK and they were not as high above sea level as we were. Nobody else believed me when I told them that and my cookery teacher at high school laughed when I told her. What had sugar to do with sea level she asked? Who knows, but it worked.

Teatime, whether in the morning or afternoon, was always a sign of something, a signal. When Gran lived with us, I loved the latter teatime best as it signalled the end of the afternoon for me. The long wait of having nothing to do while she or Mom was asleep was over and Dad and Grandad would be home from work soon. Although we of course carried on drinking tea after Gran moved out, my mother didn’t make it as well as she did, or give it that certain sense of ceremony, and I always looked forward to teatime at my grandmother’s.

Later on, tea became one of the benchmarks by which I used to judge my life in England. There, such formalities have long disappeared from everyday life and a teabag in a mug takes its place, for no one has time for the leisure and appreciation of tea drinking. Sometimes I have noticed people having four to six mugs of tea a day but it isn’t the same as that one cup in the late afternoon with Gran.

Tea, my grandmother always maintained, was one of the great benefits of colonialism. In fact, she said, it was the one thing in the world that kept everyone together, the one thing everyone shared. Tea was originally grown in China, its popularity spreading to India and other surrounding countries. It was discovered by the Europeans on their exploring and colonising expeditions, but it was the British who really recognised the great quality of tea. The best thing they ever did was to take it to all their colonies, to insist that it was grown wherever it could be. Think of the Africans, Gran would say, they love tea, they have their own way of making it, but it is tea nonetheless and who do they have to thank for that? The British, who in turn must thank the Chinese and the Indians. We are all indebted to one another. Africans and Indians boil the tea-leaves with the water, the Europeans like theirs black and the British like theirs with milk; the Chinese drink green tea and the Indians have masala tea. Then there is chamomile, honeybush, rooibos, lemon: the list is endless. Tea is the one thing that links us all together.

Gran was a prolific letter writer. She wrote to everyone: friends, people she had met, me when she went away on holiday. She had beautiful handwriting, soft and curving, the kind of writing that made you want to carry on reading, as though it were the keeper of mysteries and secrets, and you were always vaguely disappointed when you came to the end of her letters, for the mystery and the promise were still there, unsolved and unravelled. She wrote copious notes, too: a note for the butcher when she ordered meat, for the plumber or painter or odd jobs man when he came round while she was at work, and for her once a week cleaner when she wanted some ironing done. I always felt that her notes gained her a certain amount of respect, that each recipient looked forward with a strange longing to those beautifully scripted lists: the meat or milk order, her grocery requirements. Even the instructions concerning her blocked drain.

‘Nobody writes any more,’ she lamented in one of her last letters to me. And it was true. She was the only person that I wrote to rather than e-mailing and shopping lists are now a thing of the past, bound to send busy butchers, bakers and candlestick makers into fits of exasperation over the dated habits of old ladies.

Gran was an avid reader. She mainly read detective novels: Agatha Christie and Ngaio Marsh. And she read a lot. She could read four novels a week easily. Too much, my mother complained. My mother never read. She didn’t have the time, she said.

‘The thing is,’ Gran would declare every once in a while, ‘crime writers depend firstly on stereotypes and secondly on routine. They depend on a certain character looking and acting a certain way and not everyone is that predictable. Sometimes someone behaves in a way that is totally out of character. People do the strangest things.’

I would nod my head sagely and agree, but it wasn’t until I was much older that I fully understood what she meant.

‘Imagine if someone asked you what you were doing on Wednesday last week at three o’clock. Would you be able to tell them? Have you got an alibi, they might ask? No? Well, how many people do have alibis for half the things they do? Does this automatically make us guilty of murdering someone? Crime novels don’t take the individual into account, that’s the problem. We are all subject to changing our minds and just because you have a three o’clock appointment in your diary doesn’t mean you have to keep to it. Do you see what I mean?’

‘What drives one person to murder,’ she said to me another time, ‘might not bother someone else. Just because your husband is unfaithful doesn’t mean you’re going to kill him, yet someone else might have chopped him into small pieces. In fact, most crime novelists presume that chopping an unfaithful husband into small pieces is a fairly reasonable reaction to his betrayal. Murder is often more understandable than forgiveness. Isn’t that strange? And yet,’ she paused and pulled her lips together, her forehead locking in a frown, ‘there are many ways to kill someone, some just take a little longer than others.’

We went to the movies once to see Evil Under the Sun and, on another occasion, to see Murder on the Orient Express. We went to the 2.15 Saturday afternoon show at Kine 600 and that night (I was staying with her) I had a terrible nightmare about it and crept into bed with her.

‘It’s just a story, you know. They’re all actors and actresses and nobody’s really dead. At the end of the day, they take off their make-up and go home for supper.’

Put like that, the film didn’t seem so scary, but, when I closed my eyes, all I could see was the man being stabbed over and over again.

‘Gran,’ I asked, ‘would you kill someone if they killed me?’

I could see her silhouette on the pillow next to me. She was lying on her back and had the sheets and blanket pulled up under her arms. I never knew how she remained so straight as she slept. Sometimes it looked the next day as though no one had slept there at all. She thought for a bit and then said ‘I could kill them a thousand times but it wouldn’t bring you back.’

‘Would you cry if I died?’

‘Of course I would,’ she said and, although I couldn’t see her face, there was a sad smile in her voice. Her hand rested on my arm and now she gently smoothed it up and down. I could feel the hair on my arm rise and flatten with each movement.

‘Do you think you’ll die before me, Gran?’

‘I hope so,’ she said, and I couldn’t hear the smile any longer. ‘Children shouldn’t die.’

You’ll never know just how much I love you

You’ll never know just how much I care

She sang quietly as I fell asleep, the words subsiding into a gentle hum. Gran had a song for every occasion.

After my grandmother’s death, I was assigned the awful task of going through her things. In her latter years she had worn mainly trousers and shirts, but in her cupboards I found ballgowns and cocktail dresses, silk shirts and pure wool skirts: even a cashmere jersey that I never remember her wearing. In her drawers were soft cotton slips and silky camisoles. ‘It’s not every girl who can be a lady,’ she once advised me. ‘Don’t get drunk, don’t swear and never, ever, laugh at a dirty joke.’

I packed her things in boxes. Things to sell, things to give away, things to keep. But there were some things I had no idea what to do with: half-used lipsticks, nearly empty perfume bottles, her hairbrush.

I learnt a lot from my grandmother. I may not be a baker myself, but I can tell when a cake is short of an egg or two. She didn’t like literature (too heavy, she said, preferring her crime novels), but she showed me how to read characters, doubt the narrator and not fall for red herrings. Never squeeze a teabag, never blow your nose in public and never ever trust the man without the scar on his left cheek, for he’s the one that did it.

*

The phone rings a couple of times and I lean over and switch the answering machine on. I don’t want the present, although it insists on intruding. I turn to my notebook, in which I have written a couple of sentences. If only I knew where the beginning was. If only I could remember everything.

That’s why, dar-ling, it’s in-cred-ible

That someone so un-forgettable

Thinks that I am

Unforgettable too.

Chapter Four

My grandmother never cries in front of me. At her flat there is only laughter and treats; chocolate biscuits with tea at ten o’clock; jelly and ice cream to eat in front of The Muppet Show on Saturday nights. She always sets a tray for tea and puts a flower in a vase. She lets me have a bubble bath and stay up late. Sometimes we go swimming at Borrow Street and buy lollies on the way home.

I never see her crying. Once, years later, before I move to England, she tells me that the day her son died was the last time she ever cried. Nothing could ever make her feel that pain again. But I know, I know she cries when she thinks I am not there.

*

Back then Gran and I had one secret, although the number was to increase significantly in the next few years. Every Sunday, Gran would go to morning service. It was not held in a conventional church with stained-glass windows and wooden pews. Instead, it was in an old hall, also used by the Girl Guides and the Women’s Institute for their meetings. It was run-down and needed a coat of paint, but it was clean and thoroughly swept out every week. There was a long trestle table near the front of the hall covered with a white tablecloth. On top were placed two vases of roses and a Bible. It was no ordinary church service either and my mother, even though she was not religious in any sense, would not have approved. There was no piano or organ; we had to sing without music. Two people sat at the table, one who read the prayers and the lesson, the other the clairvoyant who received messages from ‘the other side’ and relayed them to the congregation. At first I did not understand what was happening and why the messages were generally very vague.

‘Is there someone here whose name begins with ‘P’?’ the clairvoyant might ask, or ‘I have a message from someone who’s holding a wooden spoon in his hand. Does anyone know who I’m talking about?’

I thought the clairvoyant had been given a message to give to someone in the congregation by someone alive. When I found out that the messages came from dead people I was horrified. I feared death, and talk of ghosts and spirits scared me terribly. Gran explained to me that these weren’t the ghosts of storybooks: headless horsemen and monsters dragging chains across castle floors, but spirit guides or guardian angels. Gran said that when you died your spirit stayed alive and you became a guardian of someone on earth whom you had loved dearly. The way that you communicated with them was through a clairvoyant: a person with the ability to see and talk to spirits. When we first went to the church, Gran didn’t receive any messages at all. Some people’s guardian angels, it seemed, were very active, while others seemed not to care about their human charges, for I noticed that it was often the same people every week who received messages.

One night I was staying with Gran and looking forward to a night in front of the television. I was allowed to stay up much later with her than at home, a privilege I did not let my mother know about. Before the late night film started, she made tea in her big orange teapot and took out two cups and saucers. Two toasted teacakes lay on a plate, oozing with butter.

‘Go and get me a clean tray cloth, won’t you, Ellie?’ Gran asked me, and I went obediently and looked for one in the linen cupboard. I couldn’t reach the shelves where the cloths were kept, so I went and fetched a chair to stand on. I saw the blue cloth that Gran normally used, but I wanted to find a different one in order to give the evening some sense of occasion. I was rummaging in the back of the cupboard when I found a green beret. It looked like something someone in the army would wear. I put it on, pushing it down on my head as it was so big, jumped off the chair and marched into the kitchen where Gran was just stirring the pot. I saluted, stamped my foot and said ‘Yessir!’ Gran looked up, the beginnings of a smile curving her lips slightly. But it died at the sight of me. Immediately I knew I had done something wrong.

‘Oh, Ellie, take that off, please,’ she said, in a deathly hushed voice that was worse to hear than if she had shouted at me. I reached up and took the cap off.

‘What’s wrong?’ I asked, turning it over in my hands.

She swallowed hard and put the lid on the teapot. There was a pause and then, ‘It was my son’s’. There was another pause. ‘He died.’ I looked down at the cap and my stomach contracted. I had held something of his. I had touched it. Not only that, I had joked about it: joked about someone who was dead. ‘He was killed during the war,’ she continued. ‘Please put it back, Ellie.’ I turned and went back to the cupboard, put the cap back and picked up the blue cloth. All thoughts of finding a more rarely-used one were gone. I thought it best to stick to the tried and known in case I opened up another slow-healing wound.

The next day we went to church and got there slightly earlier than usual. Gran got talking to Mrs Coetzee who wanted her to help out with serving tea every week after the service. Gran was unsure: she didn’t know if she was going to carry on attending church, or at least as often as she had been. I think she was disappointed she hadn’t received any messages. Every Sunday as she drove home she was very quiet and when she smiled it was sadly, as though she were trying to accept some terrible truth about life.

Mrs Coetzee was one of those people who talked incredibly slowly and who took a long time to get to the point, implying that making tea was a lot more difficult than it appeared and the responsibility it entailed was something that could not be bestowed upon just anyone. I stood by Gran’s side, patiently at first, but gradually more and more restlessly. I crossed my legs and tried to turn my head as far back as possible but lost my balance and stepped on Gran’s foot.

‘Ellie!’ she exclaimed, turning sharply to me. ‘Stand still!’

A large lady in a purple and blue kaftan was standing close by and saw what happened. She came across.

‘Have you seen the library?’ she asked me in that bright patronizing way I associated with aging primary school teachers: women who think they possess some charm irresistible to small children but who, in reality, actually scare them. ‘Come with me, dear,’ she continued before I could answer. She took my hand in an attempt to lead me away. I stood my ground and looked appealingly up at Gran for help, but it was not to come.

‘Go with the nice lady,’ she said, giving me a gentle push. I felt my heart fall to the bottom of my stomach, and had the incident the night before not happened, I may have become sulky and openly despised the large lady and tried my best to make Gran feel guilty. As it was, I allowed myself to be led away.

The ‘library’ was a small room at the back of the hall with two kitchen chairs in it and a coffee table. There was also a small cabinet with a rounded glass front. Inside it were two rows of books. The lady busied herself looking through them and emerged with three rather worn items. None of them were suitable for children and I looked at them despondently. Two were hardcover books with faded gold writing on the spine. They looked depressing. The other was a thin paperback with a plastic cover. The title read Mind Power and on the right hand corner of the cover was a yellow star with the word ‘NEW!’ in red letters. Underneath it said: ‘1978’s US bestselling title!’ All of a sudden I felt an overwhelming urge to cry. Here I was, abandoned to the whims of a large overbearing woman whom I did not know, being offered books to read whose hard, faded covers threatened some sort of punishment, a berating for the previous night’s discovery.

The large overbearing woman left me after being called by another member of the congregation to meet a visitor to the church. I was left alone in the room, perched forlornly upon one of the chairs. I sat with one of the books open and tears welling up in my eyes. Just as I could feel the first trickles down my cheeks, someone came into the room. It was someone I hadn’t seen before: a tall, thin, slightly stooping man with grey hair and trim grey sideburns. He had on an old dark suit and I remember that one of the buttons on it was navy blue whilst the rest were black. He had a slightly bristly chin and his breath, when he came closer, smelt of coffee.

‘Hello, my dear,’ he said, smiling and looking rather quizzically at my reading matter. ‘What are you reading there?’

I showed him the books and his eyes widened comically. ‘My, you must be a clever girl if you’re reading these!’ There was a pause. ‘Are you reading them?’

I shook my head sadly, trying very hard not to cry.

‘Are you here on your own?’

I shook my head.

‘Is your mother outside?’ he probed.

‘My gran,’ I answered. My voice was just above a whisper as I struggled to hold my tears back.

‘And who’s your granny?’

‘Her name is Mrs Rogers. But her friends call her Evelyn.’

The man smiled. ‘Is she the lady talking to Mrs Coetzee?’

I nodded.

‘Has she deserted you then? Or did you get tired of the ladies talking? Ladies can talk for a very long time!’

I tried to get some sort of answer out, but suddenly found myself crying. I hated crying in front of strangers.

The man looked concerned and was obviously troubled by my behaviour.

‘Are you in the dog box?’ he asked. ‘Is Granny cross with you?’

I nodded through my tears.

‘Do you want to tell me what’s happened?’ he asked and I nodded again.

Eventually my tears subsided into a sniff and he handed me a handkerchief. ‘Keep it. My wife gives me them every Christmas. I try and get rid of them during the year so I have a use for the ones she gives me the next time.’

I smiled weakly and dried my eyes with the large brown check handkerchief. There was something comforting about the man. I felt he was genuinely concerned that I was upset, not dismissive or derisive as many adults can be.

I told him what had happened the previous evening and he nodded sympathetically every now and then, his arms crossed in front of him. He didn’t interrupt me at all and, when I had finished, sat for a few seconds in thought. I felt relieved to tell someone about the episode. It wasn’t something I normally did; most of the time I kept things to myself. Finally he said, ‘Has your granny ever told you about her son before?’ I shook my head. ‘I see,’ he nodded his head slowly. ‘She doesn’t want it discussed.’ He seemed to say the last comment more to himself than to me. Just then there was a knock at the door and a head looked round.

‘We’re just starting, Mr Philips.’

‘Oh, yes,’ he said, rather startled. ‘Just coming.’ The head disappeared and the man turned to me, ‘Your granny’s not cross with you, you know.’ He got up and went to the door, still rather distracted. ‘I must go. The service is about to start. She will be looking for you.’

I slid off the chair and put the books back in the cabinet, then followed him out of the room.

The man was right. Gran was looking around for me. She smiled when she saw me and didn’t seem to notice that I had been crying. I was relieved. We found a place to sit just as the rest of the congregation started singing ‘Guide Me O Thou Great Jehovah’. I looked for the tall man, but couldn’t see him anywhere. It was only when the service started that I realized he was sitting up at the table. Once the prayers and the reading were over, Mrs Johnstone, one of the church organizers, stood up and introduced a visiting clairvoyant from their branch in Kwekwe, a Mr Philips. Suddenly I was seized with panic. I felt like I had told a teacher some secret that they felt must be told to my parents. My palms began to sweat and I kept looking down at my feet to avoid catching his eye.

Mr Philips was not much different to the other clairvoyants who graced us with their presence every Sunday. He spoke in vague terms about someone with a red hat, someone who liked pickle sandwiches and a man called Fred who wanted to tell his wife not to worry as everything was going to be all right. Then he looked our way. He stared for about half a minute. My heart was beating fast. What would he say? Would he tell her? His body trembled suddenly and he closed his eyes.

‘I have the name Evelyn,’ he said. I felt Gran start beside me. She put up her hand and I could see she was shaking. He opened his eyes, but although he was looking at us, it was as if he didn’t see us at all. Instinctively, I looked over my shoulder, but the only people there were Mr Hunter and his sister, Mrs Braxton, sitting in the row behind us.

‘I have someone here,’ he continued. ‘I don’t have a name, but it’s a young man.’ Gran sat stock still beside me. Mr Philips’s forehead furrowed slightly as though he were confused about something. ‘There’s something about his clothes,’ he said, shaking his head. ‘He’s wearing a uniform… some sort of uniform.’ His voice trailed off a little and then he added, ‘I think he was in the army’.

I turned to look at Gran. She had her hand over her mouth and her eyes held a startled look. ‘It’s Jeremy,’ she whispered. ‘It’s Jeremy.’

Mr Philips nodded and half smiled. ‘He says to tell you not to worry. He’s OK. He says something… something about tea.’ There was a murmur of laughter in the congregation. Gran’s love of tea was well known. Mr Philips closed his eyes and I could see his lips moving slightly, as though he was talking to someone. ‘Yes, tea,’ he said aloud, ‘something about doing something with tea.’

‘And otherwise,’ said Gran, ‘otherwise, he’s all right?’

‘Yes,’ smiled Mr Philips. ‘He’s fine.’

When Gran and I left the church that day, she was in a very good mood, smiling and laughing with something like the relief of someone who has been dreading something that has turned out all right. Before we drove away she had thanked Mr Philips for the message. He shrugged and said it wasn’t up to him: it was up to the spirits who communicated with him. He was standing with a cup of tea in his hand and, as Gran left him, he raised it and said ‘Remember.’ He smiled at me and turned away to talk to someone else. Gran looked for Mrs Coetzee and told her that she would help out serving the teas after the service. She left feeling very satisfied with life that day.

*

Three months after her funeral, I am back in England. I can’t sleep at night. I am haunted by the loss of her: the letters that don’t arrive anymore, the phone calls I no longer make. There is a space, a hole. I feel like a trapeze artist waiting for her partner to swing across to her, arms outstretched, but there is no one there. Would it have been easier if we’d said goodbye? If I could just have held her hand?

I find myself looking in the phone book for the address of the nearest Spiritualist Church. I sit through the service; I wait for the messages. There are none for me. I go the following week, and the week after that. Still there is nothing. I walk home in the rain, my coat pulled close. Part of me wants to let it go, to let it fall open and have the wind and rain whistle into me, through me. I want it to wash away all that I feel, to numb the pain.

I think: she is with him and she is happy. But what about me? What about me? I want to scream. What do I do now?

Chapter Five

A letter drops through the door onto the carpet. It is in a blue envelope. I feel a sharp stab of pain, a longing, and then I realise it is from her, from Gran, but it can’t be. She’s been dead for nearly six months. ‘Missent to Malaysia’ is stamped on the front. Malaysia? It was posted in Bulawayo on the 16th of October, five days before Gran died. I am afraid to open it. It is from a dead person. She was the last person to touch the letter inside. I can stand a trip to the Spiritualist Church in the hope that some message will come through from her, but not this, not so literal a message as this.

But I succumb, of course. I open the envelope with a knife… I pull the letter out carefully, fold back the thick paper and read:

My Dearest Ellie,

You are so much in my thoughts recently that I feel I have to write to you and let you know what I am thinking. I feel you are desperately unhappy, so unhappy that you have forgotten what happiness is and you accept this state as ‘normal’. I think you’d take yourself by surprise if you were to suddenly find something funny and laugh. I do not feel your smile any more in our conversations, what few of them we have, and even your letters lack their old joie de vivre. And then your dream. That’s why I had to phone you last week. Something is wrong and somewhere, somewhere in your consciousness you acknowledge this, but the thinking, rationalising Ellie won’t do this. The ring around the bath – it’s a warning. Of what, Ellie? You must think.

As I draw near to the end of my life, I realise what’s important. What to keep and what to give away – what to cut out. There are things, too, that I want to set straight, sort out, explain. Not all of this includes you: much appertains to your mother and grandfather, but I doubt if it will ever be quite resolved.

I want to face death prepared. I will come like a thief in the night, said Jesus. I need to be ready. I need to talk to you, Ellie, properly, face-to-face, and that is why I have decided to come and see you. I have not been to England for many years. I thought I’d never return, but I need to see you. Let me know when the best time for me to come would be. I know you don’t have a big house and I wouldn’t expect to stay for a long time. A couple of weeks at most. England was my first home and I would like to say goodbye to it as well. Nothing morbid, mind. Sometime in the spring or early summer is what I’m aiming at.

You’ll write soon, Ellie, won’t you? I do worry about you so much and only want to see you happy.

All my love,

Gran XX

*

I first went to the Bulawayo Naval Club in 1983. If I remember correctly, it was a Saturday afternoon and Gran and I had spent the morning in town shopping. It was an extremely hot day, probably sometime in November. The rains hadn’t started and day after day the sky stretched pale blue from one end of the horizon to the other. Gran had looked up at the sky that morning and shaken her head. ‘Not a cloud in sight. Should’ve started by this time of the year.’

That Saturday was the same as any other except that Gran had bought me a new pair of shoes. They were red sandals. I had tried on just about every pair in the shop before choosing those and, to be honest, I had only chosen them because Brenda Thomas at school had a pair. I am not sure whether I liked them myself, but I remember that the shop assistant looked up at the ceiling and mouthed the words ‘thank you’ to an omniscient god. Gran laughed and said she, too, had been about to call upon divine intervention if I hadn’t finally made up my mind.

As I wanted to wear the new shoes, my old ones were packed up in the shoebox and I carried it under my arm to the car, constantly looking down at my new red sandals. While Gran unlocked the car, I stood looking at those new shoes, my feet placed firmly together. When I looked up, Gran was holding the door open for me and smiling at my behaviour. I leapt from the pavement on to the road and then climbed on to the back seat of the car.

‘Someone’s a happy girl,’ said Gran, laughing. She took out her lipstick and hand mirror and ‘touched up’ as she called it, squeezing her lips together and then pouting. She dabbed them with a piece of tissue paper, applied more lipstick and then ran her finger around the edge of them. ‘There may be trouble ahead,’ she sang, ‘but while there’s moonlight and music and love and ro-mance, let’s face the music and dance…’ Finally, she squirted perfume on her wrists and neck. She gave me a little squirt too. I wrinkled my nose and blinked my eyes at first, but after a while I could smell lavender. She always wore lavender perfume, so much so that it became ‘her’ smell. Because she was so used to it, she tended to put too much on, so it was possible to smell her still in rooms that she hadn’t been in to for a while. I once joked that she could never be a burglar because the police would know who it was straight away. They’d call her ‘The Lavender Looter’ or ‘The Perfumed Pilferer’. Now the smell of lavender has an odd effect on me: it is more than a perfume, it is a touch like that of a hand stretched out to lead a child across a busy street. The effect is momentary, leaving a terrible sense of loss; a lost child looking bewilderingly for a familiar face amongst all the others that loom across its way in the busy street.

I wondered why she was ‘touching up’ then, when we had finished all the shopping and it was time to drop me off at home. I couldn’t wait to show Mom my new shoes. I had asked her for a new pair just that last week but she’d said I’d have to wait for Christmas as they were too expensive. That was the nice thing about Gran now that she lived on her own. She didn’t seem to worry about money the way Mom and Dad did. ‘We only live once,’ she’d say, ‘so let’s give it hell while we’re here’.

‘I thought we’d go out for lunch today,’ said Gran as she reversed the car.

‘Where to?’ I asked, knowing that Mom was making my favourite meal of spaghetti bolognese.

‘The Naval Club,’ she answered, in the same tone of voice that one might say State House or 10 Downing Street, as though we were special guests of the Prime Minister.

‘The Naval Club?’ I repeated. ‘What’s that?’

The Naval Club had been started after the Second World War by a Major MacDowell, mainly as a social club for ex-Navy men and their dependents. As with most clubs of its type in Zimbabwe, it was mainly a drinking establishment, frequented less by able seamen than by aging alcoholics. It was different to the sports clubs whose bar counters were weighed down with the beers of their die-hard Rhodesian clientele, those who could’ve won the war if only Smith had not given in to Nationalist aggression, those who had always been on the brink of victory when Smith had surrendered. They were the same people whose stomachs got in the way of them playing tennis and for whom a game of squash involved trying to get behind the steering wheels of their cars at night to drive home, drunk of course.

The Naval Club was different in that those who frequented it were mainly British and older than the sports club types. For some reason there were quite a few Scots, a Welshman called Taffy (as all Welshmen seem to be called, except in Wales itself), an Irishman called Paddy (as all Irishmen seem to be called) and a number of Englishmen (all from the north of England, whose accents made them hard to understand, especially after six hours of drinking). Even the born and bred Zimbabwean members had some kind of British connection, like a Scots father or a Welsh grandfather. Everyone was white. There were no women.

When we walked into the club it was like playing musical statues, when the music is cut off mid-song and you have to stand as still as possible, whatever you are doing. Had we been playing this game, it would have been difficult to judge who was ‘out’ as everyone stood so still. For a second we just stood in the doorway to the bar area and didn’t move either. Then a waiter approached us with a message. Mr Trevellyan, he said, was sitting at the end of the bar counter. He signalled to the left of the row of stools and dishes of peanuts. Gran clutched my hand and we walked across the silent room with what felt like a hundred pairs of eyes following us.

‘This is Mr Trevellyan, Ellie,’ said Gran. ‘Say hello.’

Still holding Gran’s hand, I edged closer to her and, biting the fingers of my other hand, said ‘Hello.’ I looked down at my feet immediately I had said it.

‘She’s shy,’ said Gran, with a rather high-pitched laugh.

I could see that the last person Miles Trevellyan expected that afternoon was me. He looked slightly annoyed, acknowledged my greeting with a light tilt of his head and turned to offer Gran a drink. I noticed he was wearing white canvas shoes that looked oddly out of shape, as though they had been shrunk in the wash and then someone had tried to stretch them back to their original size. He was also wearing light yellow cotton drawstring trousers and a white golf shirt that had a pocket on the left-hand side with the words ‘Club Med’ sewn on in light-blue cotton. Underneath the words were three wavy dark-blue lines that represented, I supposed, the sea.

I made up my mind then and there that I didn’t like Miles Trevellyan. Whenever anybody asked me why I never liked him, I always thought of that first meeting, his look of disappointment, his way of dismissing me as a child, an encumbrance, something that stood between him and Gran. ‘What would you like to drink?’ he asked Gran. ‘Gin and tonic? Vodka tonic? Beer shandy?’

‘Gin and tonic,’ said Gran. ‘With ice.’