8,39 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Gill Books

- Kategorie: Wissenschaft und neue Technologien

- Sprache: Englisch

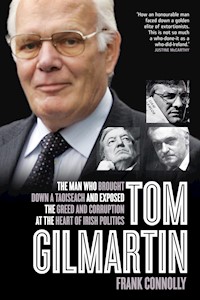

A successful property developer in England, the Sligo-born Tom Gilmartin had ambitious plans for major retail developments in Dublin in the late 1980s. Little did he know that in order to do business in the city, senior politicians and public officials would want a slice of the action … in the form of large amounts of cash. Gilmartin blew the whistle on corruption at the heart of government and the city's planning system, and the fallout from his claims ultimately led to the resignation of the Taoiseach Bertie Ahern in 2008. Written by Ireland's leading investigative journalists, Tom Gilmartin is a compelling narrative of official wrong-doing and abuse of office; it lifts the lid on the corruption and financial mismanagement that blighted Irish society in latter decades of the twentieth century. The product of two decades' research, it's a must-read for anyone seeking to uncover the roots of Ireland's financial catastrophe.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2014

Ähnliche

TOM GILMARTIN

The Man Who Brought Down a Taoiseach and Exposed the Greed and Corruption at the Heart of Irish Politics

FRANK CONNOLLY

Gill & Macmillan

For my parents, Frank and Madeleine, who instilled in me the wisdom and humanity of an equal and just society.

CONTENTS

Cover

Title page

Dedication

Preface

Prologue: It started on the ‘Late Late Show’

Part 1: An emigrant’s return

Chapter 1: The long road from Lislary

Chapter 2: ‘An ideal spot for development’

Chapter 3: The corridors of power

Chapter 4: ‘The place was totally corrupt’

Chapter 5: ‘They’ll take your money and they’ll still do nothing for you’

Chapter 6: ‘The Night of the Long Knives’

Chapter 7: ‘The Big One’

Chapter 8: ‘He was an honest man’

Chapter 9: ‘I don’t want to see the sky over Dublin again’

Part 2: The witness

Chapter 10: ‘A personal political donation’

Chapter 11: The Starry O’Brien affair

Chapter 12: ‘Sin a bhfuil’

Chapter 13: ‘The invisible man’

Chapter 14: The Mafia and the monks

Chapter 15: ‘As far as I can remember’

Chapter 16: ‘A shocking lie’

Chapter 17: ‘Loans from friends and gifts from strangers’

Chapter 18: ‘Planet Bertie’

Chapter 19: ‘I paid the price, boy’

Chapter 20: ‘You must be pretty short of material’

Chapter 21: ‘Owed an apology by the state’

Postscript

Appendix 1: Extracts from the final report of the Tribunal of Inquiry

Appendix 2: Statement by Owen O’Callaghan

Notes

Acknowledgements

Images

Copyright

About the Author

About Gill & Macmillan

PREFACE

Tom Gilmartin believed, as many of the Irish diaspora still do, that it was his responsibility to assist in stemming the tide of emigration that forced so many young people of his and later generations to England, the United States, Australia and many other far-flung places to seek decent work and a better life.

The graft and corruption described in the 2012 report of the Mahon Tribunal, which destroyed his efforts to develop his ambitious business projects and create substantial employment in Ireland during the late 1980s and early 1990s and almost caused his financial ruin, sowed the seeds of the recent economic collapse that has so deeply indebted future generations of Irish people. For this reason, the story of his journey from humble origins in the west of Ireland to success in the world of mechanical engineering and property development in England and his return to do business in Dublin deserves to be told.

I first spoke to Tom Gilmartin in the summer of 1998, a year after the Tribunal of Inquiry into Certain Planning Matters and Payments was established by the Fianna Fáil and Progressive Democrat coalition Government and a few months after its legal team had tracked him to Luton in order to hear his extraordinary allegations concerning his encounters with the political and planning systems in Dublin.

Gilmartin’s claims were more dramatic, and more sensitive, than anything I had come across in years of investigating official wrongdoing by politicians and public servants. It centred on how he was forced from control of the company he formed to develop an ambitious retail and business park at Quarryvale, near Lucan in west Dublin, now the site of the commercially successful Liffey Valley Shopping Centre.

Work on this book began in 2004 but could not be completed, primarily for legal reasons, until Tom Gilmartin and the other characters central to the Quarryvale module of the tribunal had given their evidence and the inquiry had published its conclusions, which it did in the spring of 2012. Those conclusions largely vindicated the version of events provided to the tribunal by Gilmartin, who had been accused of inventing his various claims regarding the behaviour of various politicians and public servants he encountered.

This story is based on direct interviews with Gilmartin over several years, his private statements to the tribunal, his public evidence and that of many other witnesses, and other documents and information from a range of sources. It also leans heavily on the complex four-volume 3,000-page report of the tribunal and its damning conclusions, and I believe it helps to make the tribunal’s detailed investigation into Gilmartin’s claims more readily accessible to a wider audience. The report exposes deeply disturbing questions concerning the political culture that prevailed in Ireland during those years and the manner in which systemic corruption contaminated other organs of the state, including the civil service, the Garda Síochána, the legal system and the media.

Tom Gilmartin was initially reticent about his life and that of his family being the subject of a book. Indeed one chapter concerning some extraordinary events in Luton during the 1970s and 80s that dealt with the mistreatment endured by many in the Irish community in Luton during the conflict in the North of Ireland was removed at his request. He emerged with nothing but credit as a reluctant mentor and adviser to those in the Irish community who sought his assistance during those dark years.

Eleven years after he proposed the establishment of the inquiry to the Oireachtas, Bertie Ahern was forced to resign as Taoiseach because of its investigation into his personal finances and the large and unexplained amounts of money he accumulated when he was Minister for Finance in the early 1990s. Ahern’s resignation, in April 2008, resulted directly from information provided to the tribunal by Gilmartin. However, the tribunal did not directly link financial transactions that Ahern could not adequately explain to the claims it heard from Gilmartin. For this reason the following narrative makes a clear separation between the conclusions of the tribunal in this regard and the role played by the former Taoiseach in the Quarryvale affair and his involvement with Gilmartin and the prominent Cork businessman Owen O’Callaghan, who ultimately took control of the retail development.

In September 2008, only weeks after the tribunal completed hearing public evidence, the Government led by Fianna Fáil plunged future generations of Irish people into austerity when it agreed to guarantee the billions in debt of the country’s insolvent banks, including Allied Irish Banks and Anglo-Irish Bank, and of Irish Nationwide Building Society, all of which feature in this story.

In early 2011 Fianna Fáil was devastated in a general election three months after the Government it led was forced into the arms of an EU-ECB-IMF loan facility.

The circumstances that brought the country to its knees have been well explored and documented by others, but it is my hope that this book will assist those seeking answers to the question of where the political and financial rot began that has wreaked such havoc on the lives of so many Irish people. The final report of the Mahon Tribunal, published in March 2012, revealed in shocking detail the level of political and corporate corruption and deceit that prevailed in Ireland over many decades.

In exposing the treatment he endured at the hands of some of the most powerful and influential in Irish society, Tom Gilmartin helped to expose the greed that motivated many in the corridors of power during those times. In conversations during what were to be his final days, he expressed his hope that he would be around to see this work published. He believed that the tribunal report had been put on the proverbial shelf by the establishment and that his story had yet to be properly told. Unfortunately, he did not live to see the publication of this book, despite his strong wish to do so. Tom Gilmartin died unexpectedly in Cork University Hospital on Friday 22 November 2013.

PROLOGUE

It started on the ‘Late Late Show’

It was a normal Friday night in the home of the Gilmartin family in Luton, Bedfordshire. As usual, Vera Gilmartin and her husband, Tom, were watching that evening’s ‘Late Late Show’, the long-running and sometimes controversial chat show on RTE Television. The programme was available to its large audience in England through a live satellite service provided by Tara Television of London.

The programme broadcast on Friday 15 January 1999 was hardly memorable until its host, Gay Byrne, introduced the Irish member of the European Commission and former Fianna Fáil minister, Pádraig Flynn, as a guest. A former schoolteacher from county Mayo, Flynn was one of the country’s more colourful politicians and could always be counted on to enliven a television debate, usually through some controversial, and sometimes outrageous, observation. It was he who notoriously referred to Mary Robinson’s ‘new-found commitment to the family’ during the 1990 presidential election campaign, querying whether she had ever played the role of a proper mother or housewife during her long career as barrister, human rights and feminist activist, senator and advocate for the marginalised. It was a remark that backfired spectacularly on Flynn, and Mary Robinson went on to achieve a historic victory over the Fianna Fáil nominee in the election.

Flynn’s appearance on the ‘Late Late Show’ came four months after an allegation had surfaced that in 1989 he had accepted a donation of £50,000 from a property developer, Tom Gilmartin, which was intended for Fianna Fáil but which, it was claimed, the party never received. When the story was first published, in September 1998, Flynn denied that he had received the money from Gilmartin. The claim was now under scrutiny by the Tribunal of Inquiry into Certain Planning Matters and Payments, which was set up to investigate corrupt practices in the planning system in Dublin.

After some initial chat about Flynn’s EU career, during which Flynn was his usual ebullient self, Gay Byrne asked, ‘What are you going to do about the Flood Tribunal and the £50,000 [and] Gilmartin?’ The family watching in Luton had paid little heed to the conversation up to that point, but Flynn’s answer and his subsequent comments on the Gilmartins created outrage in the household that would eventually lead to the exposure of unheard-of depths of corruption back in Dublin and, ultimately, the fall of a Taoiseach.

Flynn’s immediate response was to adopt his usual jocular tone and say, ‘Well, I want to tell you about that. I’ve said my piece about that. In fact I’ve said too much, because you can get yourself into the High Court for undermining the tribunal, so I ain’t saying no more about this . . . except to say just one thing, and this is all I’ll say: I never asked nor took money from anybody to do favours in my life.’

Prompted by Byrne, ‘But you know Gilmartin?’ Flynn replied, ‘Oh, yeah, yeah. I haven’t seen him now for some years. I met him. He’s a Sligo man who went to England and made a lot of money. Came back. Wanted to do a lot of business in Ireland. Didn’t work out for him. Didn’t work out for him. He’s not well. His wife isn’t well. And he’s . . . he’s out of sorts.’

Winding up that section of the interview, Byrne pressed Flynn with a last question. ‘But you’re saying you never took money from anybody at any time, for whatever reason?’ Looking directly at his questioner, Flynn replied with a variation on his earlier denial, saying, ‘I never took money from anybody to do a political favour as far as planning is concerned.’

After that the conversation moved on to other matters, with Flynn complaining about the fact that his daughter, the Fianna Fáil TD Beverly Cooper Flynn, had been the victim of allegations of irregular practices when she worked for National Irish Bank. He also remarked how difficult it was for him to survive on an annual salary of £140,000 when he had to look after three homes, raising eyebrows all over the country when he moaned about the cost of maintaining his three separate houses in Brussels, Dublin and his native Castlebar, county Mayo. Running three homes, with three housekeepers, was a ‘very expensive business,’ he said, and he suggested to the audience: ‘Try it some time.’

Flynn might have thought this latter bit of frivolity would be what would be talked about next day, and that his comments on the Gilmartin issue would be forgotten. He couldn’t have been more mistaken.

In the Gilmartin household Pádraig Flynn’s comments went down like the proverbial lead balloon. Vera Gilmartin, an intensely private woman, became upset as she heard herself and her medical condition discussed on live television. Christmas 1998 had been a hard time for them, as Vera’s multiple sclerosis had gradually worsened over the preceding months and she was largely immobile. Now her family and friends in her native county Donegal and the length and breadth of Ireland were watching this politician making ill-considered remarks about herself and her husband.

Tom’s sister Una phoned RTE from her home in Sligo to complain, and researchers on the show contacted Flynn. As the two-hour show neared an end, Gay Byrne told viewers that ‘Pee’ Flynn, as he was known to the public, had corrected his earlier comments about Tom Gilmartin. ‘In the interview it was suggested by Pee Flynn that Tom Gilmartin was sick. As far as Pee is concerned, Tom Gilmartin is not sick and has never been seriously sick, and we would just like to say sorry and apologise for that,’ Byrne said.

But it was too little, too late.

As the show ended, the telephone in Luton began to ring, with friends and family from Ireland calling to express their concern at Flynn’s performance. Tom Gilmartin was furious. ‘When I saw that clown on TV I was incensed,’ Gilmartin told me in the days immediately after the programme. ‘The only thing that was missing was the red nose. I never wanted to be the centre of attention, and I never wanted my wife to be involved in any of this. And then that comedian went on TV. The irony is that Flynn was not the worst of them, and I’m not saying that because he is from the west of Ireland.’

On the morning after the programme Gilmartin’s home was under a media siege. Television crews and newspaper journalists set up camp outside the house, pleading for Gilmartin to give more details about his claims of corruption in Dublin. Some months earlier Gilmartin had revealed to a number of journalists some details about the donation of a £50,000 cheque. He said that Flynn had asked him to leave the payee section of the cheque blank, and that it had never been passed on to Fianna Fáil, as intended.

Notes seeking interviews were dropped in the letter-box, and one reporter delivered a bouquet of flowers, presumably for Vera, in the hope of getting a chat with the man now at the centre of a mounting political storm in Ireland.

Gilmartin decided to throw a couple of highly charged grenades in the direction of those now seeking to depict him as ‘unwell’, as Flynn had suggested. Without too much thought, he responded to some of the media queries and confirmed that he had been contacted by Flynn when the news of the £50,000 donation, and the fact that it had not been handed over to Fianna Fáil, had emerged a few months earlier, in September 1998. Flynn, he said, was concerned about Gilmartin’s contact with the Flood Tribunal and wanted to know what he had told the inquiry about the donation. This revelation now placed the hapless Flynn in a position where he stood accused of siphoning off party funds as well as attempting to interfere with the tribunal of inquiry.

Flynn’s ‘Late Late Show’ performance ensured that Gilmartin’s claims became known to huge numbers of people who had previously never heard of the reclusive developer or his allegations of corruption among Dublin’s political elite.

Just as Gilmartin was besieged in Luton, so the press pack chased down Flynn back in Ireland. But the man who was usually prominent in his local church in Castlebar for Sunday mass was nowhere to be seen. He headed for the privacy of the five-star Ashford Castle Hotel, some miles from his home, where he met his party colleague and former EU commissioner Ray MacSharry for urgent consultations. Flynn had decided to keep his head down, and the usually voluble politician refused to respond to any further media queries, which, of course, only led to further speculation.

In the few comments he made immediately after the ‘Late Late Show’, Gilmartin assured reporters that his health was ‘the very best.’ He also told reporters that he had never intended to generate controversy and had been reluctant to get involved with the tribunal of inquiry set up in 1997. The fact that he had been contacted by the tribunal had already been confirmed some months earlier in the Irish media.

‘I didn’t want to get involved. I kept my mouth shut for ten years,’ he told the Irish Independent. But Flynn’s remarks had changed his mind. ‘I will be giving evidence now. Flynn has seen to that. On the “Late Late Show” he made me out to be a mental patient. I am not a bitter man, and I was never money-oriented . . . But as far as I am concerned I am the victim of the most scurrilous carry-on perpetrated right from the top—including the current top.’

Asked what he meant by this last remark, he said, ‘I think I will leave that for the tribunal. But I can tell you this: they all have a lot to worry about, right from the top. Everything I say will be proved; it will all be proved . . . What I have to tell the tribunal will explode at the heart of the current Government . . .’

It was a comment that significantly raised the political stakes; but few could have thought at the time that it would end up embroiling the Taoiseach, Bertie Ahern, in such a dramatic political controversy, or that it would lead to Ahern’s resignation from office less than a decade later.

PART 1

An emigrant’s return

Chapter 1

THE LONG ROAD FROM LISLARY

Tom Gilmartin’s reluctance to engage with a tribunal—any tribunal—can be seen in a comment he made on hearing of the decision by the Revenue Commissioners in December 1998 to waive any tax demand on the disgraced former Taoiseach Charles Haughey after details of his illegal Ansbacher accounts had emerged in an earlier judicial inquiry. In his typically blunt fashion, Gilmartin said that ‘tribunals are about as useful as tits on a bull.’ The expression, picked up from his early days living on the land in county Sligo, was published, to much amusement, and provoked more questions about the nature and background of this character who had emerged sensationally onto the already crowded set of the tribunal drama.

So who was Tom Gilmartin? And how had this west of Ireland lad become such a significant player in business and property development?

Born in 1935 in Lislary, near Grange, county Sligo, to James and Kathleen Gilmartin (née McDermott), Tom was the first son after three girls, Maudie, Eileen and Patsy; later came Una, James, Julann and Christina. Another child died at birth, while Julann died at six months. James Gilmartin supplemented his income from the thirty-acre farm with his various skills: he made shoes, harnesses for horses, and was a carpenter as well as a champion ploughman. Using expertise he had acquired with explosives during the War of Independence, he also did blasting work for the county council.

Tom Gilmartin was encouraged by his father to work with him on the land. He left school at thirteen, having decided that he was learning nothing there. ‘It was a small national school with one teacher, who chain-smoked and was quite heavy-handed with the stick, to say the least. The only thing I ever saw on the blackboard was Tá mé go maith [I am well] and Sin é an madra [That is the dog]; we never learnt much else. I wanted to learn, but there was nothing. You had to bring a sod of turf every day for the fire. The place was freezing, and there was ice on the floor in winter time, and the teacher would have his arse to the fire all day.’

He got his first job cleaning drains with the county council after altering the age on his birth certificate from thirteen to sixteen. He also helped his father with work on a land reclamation scheme recently introduced by the Government. For a few years the work of clearing scrub and briars, draining and reclaiming land, took up his days. However, he was ambitious for more, and at night he attended the local technical school, despite his father’s opinion that there was little worth in the education there.

Through perseverance, and despite missing years of formal education, he won a scholarship to the agricultural college at Ballyhaise, county Cavan. As the course neared its end he applied for a post with the Department of Agriculture and came first in the civil service examination for the position; however, he was disqualified on the grounds that he had not completed his course, which ended the same week as the exam. His place was awarded to another young man, who had achieved poorer results but who had a well-placed relative in the public service. Several of those who gained places had ended the course at exactly the same time as the young Gilmartin, so it seemed to be a case of ‘who you know and not what you know’ that sealed his future.

Hordes of young people left Ireland for England in the 1950s. It was a reflection of the deep depression throughout the country, and it was only a matter of time before Gilmartin decided to join his many friends from Grange, Cliffoney and other parts of north Sligo who had headed for job-rich Luton, thirty miles from London, where a number of people from his home area had already settled.

‘I was back at home saving hay with my father when I stuck the fork in the ground and I said, “I’ll be in England tomorrow.” He wouldn’t believe me. He didn’t want to believe me, so he called me in the morning to go down at the hay, and I told him, “No, I’m going to England.” And he went mad and he said, “You go to England and you need never come home again.” It might have been different if I was going to America or somewhere, but he never wanted me to go to England.’

It was understandable. James Gilmartin’s past history with the British colonisers was not a happy one. Born in 1898 in Lislary, he joined the Irish Volunteers some time after the Easter Rising in 1916 and became something of a crack shot and an explosives expert. The exploits of Gilmartin and his group of volunteers during the War of Independence were the stuff of local legend. He was captured during what was also known as the ‘Tan’ war, so called after the brutal and infamous Black and Tans, the undisciplined force of irregulars, mostly former British soldiers and convicts recruited to swell the ranks of the Royal Irish Constabulary. He escaped from Cliffoney barracks with the help of an RIC officer.

The search for his group of IRA volunteers, and his subsequent arrest, followed a daring attack on the RIC barracks at Breaghwy, near his home, when another Lislary man, Dominic Hart, scaled the chimney of the high-walled house and descended into a room where the two most senior British officers were sitting down to tea. Local folklore has it that Hart, two revolvers in hand, told the officers to order their men to lay down their weapons and leave the barracks. The officers were not to know that Hart’s weapons were empty; in fact the whole purpose of the raid was to stock up on guns and ammunition, of which there were precious little among the local IRA unit. The column of British troops and RIC men left the barracks, which was promptly seized in one of the more dramatic and less well-known actions by the IRA in county Sligo.

Having joined the anti-Treaty forces after the War of Independence, James Gilmartin was lucky to escape death during the vicious and bitter civil war that tore communities and families apart. He once helped a group of volunteers evade arrest at Lissadell, the ancestral house of the Gore-Booth family and home of Constance Markievicz, by hiding them in the sea with reeds in their mouths to help them breathe. He then returned home to Lislary. Soon afterwards, pro-Treaty forces, led by General Seán Mac Eoin, dragged him out of the house and put him up against the gable wall. His mother, Mary, threw herself in front of her son to prevent him being put to death on the spot. He was taken prisoner and transported to the Curragh prison camp, in county Kildare, for the remainder of the conflict.

Some of his comrades were not so fortunate. In September 1922 the Free State armoured car Ballinalee (named after Mac Eoin’s home town), equipped with a machine gun, was captured by republicans at Rockwood, county Sligo, and was used to mount attacks on government troops. When the pro-Treaty forces launched an operation to retake the armoured car a gun battle took place near Drumcliff. The republicans took to the hills after dismantling the car and the machine gun and were pursued by government troops on the Horseshoe Mountain deep into the slopes of Benbulben. In one of the most infamous episodes of that bitter conflict, six republicans, including Brigadier-General Séamus Devins TD and his adjutant, Commandant Brian MacNeill, son of a government minister, Eoin MacNeill, were captured. After their surrender, troops under the command of Tony Lawlor, a government officer of some notoriety, shot the six: Séamus Devins, Brian MacNeill, Joseph Banks, Patrick Carroll, Thomas Langan and Harry Benson.

Two of the bodies were not found for a fortnight. The bodies of the other victims were removed by an uncle of the future Fianna Fáil ministers Brian Lenihan (senior) and Mary O’Rourke to his mother’s family home at the foot of Benbulben. The uncle, Brian Scanlon, was subsequently forced into exile in Australia because of the assistance he gave the anti-Treaty soldiers. The Free State government claimed that the men were preparing an ambush when they were shot, but republicans in the county said that the six had been shot and savagely bayoneted by soldiers after they had surrendered and had been disarmed.

The killings on Benbulben left a legacy of bitterness in county Sligo that persisted long after the final shots of the Civil War were fired. For James Gilmartin, like many on the defeated anti-Treaty side, the newborn state had been christened with the blood of too many of its young, and the reward for his contribution was a life of hard work on the soil. The victors took the spoils, including the best public-service jobs and positions; the losers returned to the land or faced the emigrant boat.

‘My father never talked to me very much about it,’ Gilmartin said. ‘If you asked him questions he didn’t answer. The six that were shot on the mountain were great friends of his. Martin Brennan was a great friend of ours too. They took him out of the house and shot him up against the wall at Mount Edward. They riddled him with bullets. A lovely fellow who had nothing much to do with anything. My father always believed he was shot for his piece of land.’

James Gilmartin took little interest in politics in later life but fervently supported de Valera and Fianna Fáil, the party joined by many of those who fought on the losing side in the Civil War. The party won power in 1932, thus ending nearly a decade of rule by Cumann na nGaedheal, which was identified with the victorious pro-Treaty forces. De Valera built a mass movement with a promise to develop an independent, self-sufficient economy, support and extend the use of Irish, and finally achieve the long-held objective of a united Ireland, which appealed to many like James Gilmartin.

Tom Gilmartin readily understood his father’s opposition to his decision to emigrate, but was determined on this course. ‘My father never wanted me to go to England. It was the old thing about England; but everybody around us, every able-bodied man, was gone. My mother was heartbroken. She had raised us well, and although there was not much money around we were always turned out in the best of clothes. She was a great cook and we always ate well. She was sorry to see any of us leave. My sister had gone before me, but she died of meningitis at twenty-three. My mother was a highly intelligent woman, and she regretted never having gone to America herself with her sisters. I am very proud of my parents, and my mother in particular. But there was no chance here at that time.’

Although reluctant to see him go, his mother would help him to advance in any way she could, while his father resisted in vain his eldest son’s departure to the land of the old enemy.

Tom Gilmartin took the boat on 27 July 1957. Arriving at Euston Station in London, the fresh-faced young man from county Sligo headed for St Pancras Station and the train to Luton. His first encounter was with a friendly English man from whom he asked directions. ‘I wasn’t quite sure where I was going. So there was this fellow standing on a corner. “Oh, you’ve just arrived,” he says to me. I said I was going to Luton. “Ah, you don’t have to go to Luton. I have a lovely place, and you can stay with me.” I thought, What a lovely fellow to meet after arriving in a strange place! The next thing this woman passed by and she looked at me. She asked if I was lost and then said she assumed I had just come off the train. She kind of moved away from the bloke, and she said to me, “Do you realise what he is?” I said no, and she said he was a homosexual. And I said, “What’s that?” She took a big fit of laughing and said, “You bloody Irish, you’re so innocent.” She pointed out St Pancras Station, which was right beside me.’

After arriving in Luton and a night of searching for digs, with many refusals by landladies who didn’t take Irish tenants, Gilmartin found a bed. A few days later he joined up with the crowd from Grange and found more permanent lodgings with an Irish landlord.

It was boom time for the British economy, with new industrial towns spreading across the Home Counties. His first job was as a conductor on the buses of the United Counties bus company. His next stop was at the Vauxhall car factory in Luton. He was put to sweeping the floors, a job that suited him perfectly, as it meant he could work seven days a week and boost his wages with overtime. After a while he was approached by a manager to help with maintenance on the conveyor system in the manufacturer’s new chromium plant, where the cars were painted. It was not long before his talent for fixing and maintaining complex engineering equipment was noticed and he was encouraged to go on a basic training course on the mechanical handling system, paid by the company. ‘I started working with mechanical handling systems, and they fascinated me. I then joined Simpsons of Round Green, who were building special-purpose machinery as well as overhead runways and conveyors.’

At Simpsons he spent several months working on Britain’s first prototype space rocket. ‘I was the only Irishman among them. They had the rocket ready, and they used to test the engines underground. When they turned on the big engines the whole town used to vibrate.’ The project was eventually closed down by the British government under Harold Wilson. Many of the scientists went to work on the NASA space programme in the United States. ‘America ended up building what the English had pioneered. It was referred to as the brain drain, because all of the scientists and specialists went to America and Germany and other places.

‘I was determined to learn about everything, so I had a chequered employment history, as I never stayed too long with any one company, because I wanted to learn something else. I did structural engineering as well. I had a plan to set up my own company over about two to three years, and I did that. I built it up with any type of engineering or steel jobs I could get. I started on my own, literally on my own.’

As well as expanding his knowledge of specialist engineering work, he took night classes in the local technical school, where he obtained a certificate in welding. He had discovered that he had the eye for precision engineering, as well as mathematical skill and excellent recall.

He also threw himself into improving the social life of the Irish in Luton. His entrepreneurial flair came to the fore in organising events within the thriving Irish community. ‘I knew a lot of Irish people, and I started the Gaelic football in Luton. I set up the Erin’s Hope club and got football pitches. Over seventy thousand Irish arrived in Luton during those few years, and there were some very good footballers from every county. There were a few clubs: St Dymphna’s, the Owen Roe Hurling Club and Erin’s Hope, where I was chairman.’

Chairman in those days was a fancy name for chief fund-raiser and bottle-washer. Tom organised dances and chartered the first aeroplanes from Luton to Dublin for football matches. ‘I suppose I was the equivalent of the first Ryanair, as it happens. We organised chartered plane trips to Dublin Airport for all-Ireland finals and other events. There was a man who came back from the war with one arm. He was a travel agent and he used to beg me to join him in setting up an airline service. I was actually offered the use of Luton Airport, which at the time was used for training pilots and testing aircraft built in the nearby factories.’

It was while he was selling tickets for a flight to a football match in Dublin that Tom Gilmartin met his future wife, Vera Kerr, who had recently arrived from county Donegal. ‘I met Vera while I was collecting money for the trip at a dance in the George Hotel ballroom,’ he said. A native of Urris, Clonmany, in the Inishowen peninsula, Vera had recently arrived in Luton with her sister, Sarah. She was from a small farming family, and she and her sisters and brothers all spent years working in England.

When Vera met Tom, who was five years older, she was working as a waiter in the Red Lion Hotel in Luton. ‘She was gorgeous, petite, and always looked much younger than her age. She was a very sensible and down-to-earth girl,’ Gilmartin said.

It was 1959, and Gilmartin was fast gaining a reputation as a man who would try any engineering job, no matter how complex or dangerous. Setting up in Cross Street, Luton, on the site of a former hat factory, he took on a variety of structural engineering and other jobs. Despite his relatively basic engineering training he was hired by some of the giant corporations in the south-east of England to come up with innovative solutions to practical problems, particularly with the developing conveyor-belt technologies. He became an expert in mechanical handling systems and special-purpose machinery, helping to design and develop the first computer-controlled conveyor systems and assembling the cast-steel equipment that put the car bodies in place.

At the Ford factory in Dagenham he helped to remove equipment weighing thousands of tonnes by constructing a special lift table. Over several weeks he manoeuvred the equipment onto his self-made conveyor system and used huge poles to gradually move it from the factory. It saved the company hundreds of thousands of pounds, as other experts had determined that the only way to move the equipment was by removing part of the factory roof. When he was asked how much he wanted for completing the job, Gilmartin asked for £200. The manager paid him and then told the self-trained engineer that he would have paid £50,000 to have the job done.

By the early 1960s Gilmartin was building special-purpose steel handling equipment required by the car and other heavy industries. He went on to specialise in the construction and installation of conveyor systems for prominent customers, including the biggest car manufacturer in the area, Vauxhall, owned by General Motors, as well as the chemical giant ICI and the prestigious Rolls-Royce.

In 1965 he registered his company, Gilmartin Engineering, with Vera, whom he married the same year, as the other director. He built a customised factory at Eaton Green Road, close to Luton Airport, and developed computerised car production systems as well as heavy lifting and handling equipment for the steel industry, to cope with the demands posed by the large and complex engineering contracts the company was taking on. The work force grew from fifty to several hundred at peak times.

Gilmartin installed the first automated conveyor at Vauxhall, which allowed for the efficient assembly and passage of car parts from the massive pressing machines to the installation of panels, wings and engines and then the final stages of chromium-plating, dyes and finishes. He came up with an overhead system worked by a panel of switches that had the added benefit of a more efficient use of space in the factory. He also developed new airport baggage-handling carousels and conveyors.

‘The real money was in the shut-down at Vauxhall over the summer. We worked flat out ripping out the old conveyor system and installing new ones. We had to have it all running on the day they came back from holiday. It meant working around the clock, twenty-four hours a day. There was no time for socialising. There were some hellish ups and downs. I was determined to make it work. It might sound romantic and exciting, but it was hard work and an absolute nightmare at times. I often went to work on a Friday and didn’t come home until the Tuesday night.’

The hard work, the constant pursuit of new skills and his innate entrepreneurial drive paid off. The immigrant from county Sligo had become a success.

But despite his achievements and the increasingly lofty circles in which he was moving, Tom Gilmartin remained very much a Sligo man. On one occasion an Irish-American senior executive of the giant American car manufacturer General Motors visited the Vauxhall plant to view the quality of Gilmartin’s engineering work. Sir Reginald Pearson, a director of Vauxhall, commented on Gilmartin’s Irish accent, asking why he hadn’t learnt to speak ‘proper’ English after all his years in Britain. It was not a remark that sat well with the Sligo man, who said he was proud of his roots and his accent. The conversation was overheard by the American visitor, who praised him for facing down the snobbery of the British director.

As Luton continued to attract Irish immigrants, Gilmartin and other expatriate business people worked hard to ensure that the social, sporting and spiritual needs as well as the employment needs of the new population were met. Father Liam Murtagh, who ministered in the city during much of the 1960s, told me how Gilmartin, along with the Connolly brothers from county Mayo, the Shanleys from county Leitrim, the McNicholases and other Irish business families helped the Irish community. ‘These businessmen had their own companies and they came together to build the Harp Club, where the huge Irish community congregated for sports and social events. They also contributed to building Catholic churches and schools in the area.’

Father Tom Colreavy, who came to Luton in the late 1960s, also remembered Gilmartin as ‘a hard-working devil who tried his best at everything . . . He was an ambitious fellow as well, and that is why I believe he was very successful in his business life. Others were very capable, but you had to admire Tom because he bit the bullet and went for it. He was very hard-working, and his family were well liked in Luton.’

In 1970, after the birth of their first two children, Liam and Anne, the Gilmartins moved from their home at 111 Merrick Avenue to a detached house at 22 Whitehill Avenue in one of Luton’s leafier suburbs, where Thomas and James were born.

Gilmartin spread his engineering work to the United States, where he assisted with major commercial projects, including the construction of monorail systems at the new Disneyworld developments in Florida and California. His work brought him into contact with the US air force and army engineering corps, for which he did design work through a new company he established, the Minnesota Engineering Group, in Minneapolis in the 1970s. He was also involved in the design of the complex engineering work used in the construction of the Silverdome, the American football venue in Vancouver, Canada, which opened in 1975.

Thousands of Irish people were still hitting the emigration trail to England and the United States. In the winter of discontent in 1978 a wave of industrial disputes pitted hundreds of thousands of workers in Britain against the Labour government, which continued when an ascending Conservative Party, led by Margaret Thatcher, came to power one year later. The disputes affected Gilmartin’s business and, while his employees were not on strike, the work force was effectually prevented from working, though he continued to pay their wages for months.

Eventually he was forced to wind up Gilmartin Engineering in 1981, resulting in more than four hundred workers losing their jobs. ‘You were only as good as the next contract. We were working night and day just to keep our heads above water. We had to quote prices below cost. The economy was in free fall. Thatcher took on the trade unions and destroyed the steel industry. All our bread and butter was gone. The car industry was a shambles. I couldn’t compete with the big players, who were bidding at a loss for contracts. I put the company into liquidation.’

For the determined Gilmartin it was time to explore other avenues. He got £1 million for a factory he had been building in Northampton that was almost finished. Using these funds, he began a business in which he identified suitable sites for office and retail property schemes, which he then helped to design.

Gilmartin made the transition to property developer with some ease. In his first foray into this area he acquired, and then sold on, a proposed scheme in Milton Keynes, a town north of Luton where a new city was under construction. The sale raised another £1 million for Gilmartin, which helped restore his finances after the difficult years trying to keep his engineering business afloat. He worked with the auctioneer Richard Forman of Wilson and Partners (later Connell Wilson) in designing other schemes for office and retail developments and selling them on before construction.

Among the schemes he was asked to examine was a planned development at Tiger Bay, close to the home of Welsh rugby at Cardiff Arms Park. He controversially proposed the demolition of the ‘Park’ and the construction of another one at a different site, though he was not involved in the project that was completed in 1999, when the Millennium Rugby Stadium was constructed on a much expanded and redeveloped Cardiff Arms Park.

Through various projects Gilmartin restored his finances, and after a few years of astute property investments he accumulated several million pounds, which ensured that his family would enjoy a comfortable lifestyle in England. In the course of his work in property development he was getting a name for himself as a shrewd investor who recognised the commercial potential of sites throughout the country, and as a consequence he came to the attention of senior executives in the major finance companies and pension funds, including Capital and Counties, the London Edinburgh Trust, and Norwich Union. His ability to identify potentially profitable property schemes and to envisage their long-term development was widely recognised, and his services were in significant demand as the British economy recovered. His contacts at the highest level within these finance houses provided him with access to capital for investment and also introductions to the main retailers that would anchor various schemes, including such prominent retail names as Marks and Spencer, Selfridge’s and Boot’s.

Gilmartin was now regarded as a successful and respected businessman, not only in his community but among banking and financial institutions in England. He had an interest in the development of Milton Keynes, where he had been offered a 99-year lease on a three-acre site earmarked for the extension of the new shopping centre in the town following his successful construction, and sale, of an office block in the new city. Another project was suggested by the grandees of Winchester, who asked him to come up with a scheme for redeveloping its city centre.

At the same time that Gilmartin was expanding his business as a developer in Britain, Ireland’s economy remained in a depressed state, resulting in another wave of emigration. Thousands of young Irish men and women arrived on the streets of London, Liverpool and Luton, and Gilmartin has nothing but praise for the ordinary English people who helped them while they were looking for work and shelter during this time. The welfare state provided a basic income, and the social services ensured that the new immigrants were treated fairly. A number of Irish nuns from the Sisters of St Clare, including Sister Antoinette from Dublin (an aunt of the former Irish international soccer player Ronnie Whelan) and her friend Sister Eileen from Cork set up a day centre in Park Street for the huge numbers of immigrants still flowing into Luton. Gilmartin, along with other Irish business people and individual donors, helped them get the project off the ground.

His encounter with one such young Irish immigrant about this time was to inspire Gilmartin with the idea of investing in Dublin. ‘I was in town shopping. I came out of the supermarket with bags of groceries and was waiting for a taxi to arrive. I noticed this young fellow looking in the window of McDonald’s next door. I could see he was straining to read the menu. He put his hand in his pocket and took out whatever money was there, and he started counting it. He’d look at the money and then at the price list. He stood there for a good while. A young Irish fellow passed and said hello to him and I realised he was Irish. I started chatting to him and asked him if he was long in Luton. He said he had come a month or two earlier. He couldn’t get work. He had no luck at all. He was a decent enough young lad from Tipperary. I said, “Why the hell don’t you go home? Anything is better than the streets of Luton.” I asked him if he had any money. He was very embarrassed and said he was a bit short at the moment. He said he didn’t have the fare to go home. Then he said, “If I go home there’s no hope at all,” and that was the thing that hit me.

‘Here was a fellow walking the streets of Luton looking for a job, without a penny to buy himself a burger, but he considered going home the greater of two evils. That struck me more than anything. I told him I could understand, because I came over in the 1950s, when there was no hope either. But I felt it was a damning indictment of Ireland. I said, “If you want to go home, I’ll pay the passage.” He didn’t want to take it. I handed him some money to get himself a feed. With a bit of persuasion he took the money. I said I knew a few people in Milton Keynes and that there was work starting on a site there. I told him to mention my name. I gave him two hundred pounds and said, “That should take care of you.” He didn’t want to take it, and he wanted my address so he could pay me back. I said, “I’m all right. God is good to me, and I hope he’ll be good to you.” It was then and there I decided to see if I could do anything to help rescue the Irish economy and keep these kids at home.

‘Since Ireland was at rock bottom, it hit me that it would be a good time to start. I put the feelers out to see would there be any interest.’

Invited to a function in London attended by executives from a number of banks and investment houses, Gilmartin raised the prospect of doing business in the then flagging Irish economy. The notion was greeted with some incredulity by potential investors, who considered Dublin a backwater, with little to offer by way of a healthy return. As the event came to a close he was introduced to Raymond Mould, chief executive of Arlington Securities, and also met executives from the London Edinburgh Trust and Capital and Counties, who were more open to his ideas. After discussions with the investors in London he was told that funds were available for any potentially successful scheme he could identify in Dublin.

Gilmartin had already been invited by the Northern Ireland Office in Belfast to discuss plans for the redevelopment of Belfast along the River Lagan and of Derry along the Foyle, and had made a successful investment with local business people in the Clandeboye Shopping Centre in Bangor, county Down, which was a commercial success despite the continuing and bitter conflict in Northern Ireland. ‘I was told that money would be no object if I put the right deal together.’

Armed with that promise, Gilmartin came to Dublin.

Chapter 2

‘AN IDEAL SPOT FOR DEVELOPMENT’

The economic and political landscape in Ireland in the mid-1980s was bleak. Unemployment was at a record level, and tens of thousands emigrated every year, including many young, skilled and educated graduates. The country was weighed down by poor growth, high inflation and mounting public debt. In the North of Ireland the Troubles continued to rage, with nearly seven hundred people killed between 1980 and 1987.

What would later emerge—in part as a result of Tom Gilmartin’s evidence to the tribunal—was that there was also a culture of political and business corruption in the 1980s, and nowhere more so than in Dublin, which reached all the way to the leader of Fianna Fáil, Charles Haughey. Throughout the 1980s Haughey encouraged taxpayers to tighten their belts and after 1987 inflicted deep cuts on public services while living in a mansion in county Dublin, owning an island off the Kerry coast, buying expensive tailor-made shirts in Paris, and entertaining his friends in the luxury to which he had become accustomed.

Such a life-style would be impossible even on a Taoiseach’s salary. It was later revealed that Haughey maintained it by receiving large secret payments from businessmen during most of his career. With the help of Des Traynor, a former accountancy partner in his firm Haughey Boland, he stashed huge amounts of money offshore in the Cayman Islands, as did other well-connected individuals, all this at a time when public hospital wards were being closed through lack of funds. Haughey’s influence, and that of his party, penetrated all levels of society, and none more so than the lucrative world of construction and development.

If lands were purchased at agricultural prices around the capital they multiplied in value if they were eventually rezoned for housing or commercial developments. Advance information about rezoning was available from plans that were accessible to the politically influential. Corrupt politicians, planners and senior council officials could provide much of the information to those who were willing to pay the price.

A crucial moment was the creation in 1966 of Taca, an organisation specifically designed to allow wealthy businessmen access to Fianna Fáil politicians for a donation to the party of £100—a considerable amount in the 1960s. Taca became public knowledge in 1967, and as a result of the disquiet that resulted it was wound up in 1969, but the connections between powerful political figures and wealthy businessmen continued, although in a more informal and surreptitious fashion. But the important feature of Taca, noted even at the time, was how many of those involved came from the property and construction sectors. What Taca first showed was the deep connection between Fianna Fáil and the building industry, a connection that both would use in the future to their mutual advantage but often to the great detriment of the state the politicians were meant to serve.

The political and commercial culture in Dublin was not what Tom Gilmartin anticipated when he arrived there from Luton in late 1986. He had studied maps of the city several years earlier and had already identified possible sites for retail developments in the rapidly expanding western suburbs and the city centre. Since the mid-1970s he had also identified the need for an integrated development plan for the city and had a vision of what could be achieved, which he had discussed with the influential executives of financial institutions and pension funds he knew in London. The vision was quite extraordinary, though Gilmartin’s potential backers felt that it was a realistic objective.

Dublin at the time was run by two authorities. Dublin City Council (called Dublin Corporation at the time) was responsible for an area that extended outwards from the city centre to the suburbs of Sutton and Santry in the north, Finglas and Ballyfermot in the west, and Donnybrook in the south, while Dublin County Council (now split into Fingal, South Dublin and Dún Laoghaire-Rathdown County Councils) was responsible for the area beyond that out to the county boundary. These authorities were responsible for issuing planning permission and for rezoning lands, so any developer wishing to assemble a project needed to deal with them. At times the developer would have to work with both authorities, as lands required might cross the boundary between city and county.

The ambitious plans Gilmartin created for Dublin involved a massive reconstruction of an area linking the shopping quarter of Grafton Street with a new footbridge across the River Liffey to Henry Street, close to O’Connell Bridge in the heart of the city centre. He was in discussions through his London solicitors, Cameron Markby (later Cameron Markby Hewitt) and with several leading banks and finance houses in Britain and Ireland about these plans. Among those involved at various stages were the American banking giant Citicorp and, in Dublin, Investment Bank of Ireland and Standard Life.

The plans included acquiring a number of the leading retail names in Dublin, including Brown Thomas and Switzer’s in Grafton Street and the fashionable but at the time unprofitable Arnott’s and Clery’s in Henry Street and O’Connell Street, respectively. Gilmartin held discussions with the chief executive of Independent Newspapers, Joe Hayes, on the possible acquisition of its premises in Middle Abbey Street, which involved the proposal that Gilmartin and his investors would acquire land owned by the state transport company, CIE, near the mouth of the Liffey, where the media group could set up more modern production and printing facilities.

The figures involved were staggering, with Arlington Securities and other investors considering a scheme that would require up to £200 million in finance and the prospect of twenty thousand new jobs for Dublin. The plan also included a monorail link from Connolly Station to Heuston Station and new roadways to divert traffic from the badly choked artery along the quays. Gilmartin had an even greater long-term vision that would involve the construction of an entire new city in the midlands near Athlone to relieve the pressure on the ever-expanding capital, to which more than a third of the population had drifted over recent decades, depopulating vast swathes of the countryside and making towns and villages commercially unviable. He proposed a six-lane motorway from Cork to Derry, which he also discussed with the authorities in the North, which would open up dozens of towns along the route for residential, commercial and industrial development.

Gilmartin had recognised that Bachelor’s Walk, the strategic street along the Liffey adjoining the city’s most important and busiest thoroughfare, O’Connell Street, was ripe for development. He had also noted the Government’s plan for a ring road around the city, the proposed M50 motorway, and reckoned that there was an ideal site for retail and other commercial development where the planned motorway would meet the N4, the main road to Galway and the west. ‘I noticed the M50 and I had an idea that somewhere on the N4 around Palmerstown would be an ideal spot. I realised that was it: bingo! And then I saw Bachelor’s Walk, derelict, with half the buildings knocked down, and I thought that would also be an ideal prospect for development. I went back to England. A number of people had made me offers of funds, and Arlington Securities was one of them.’

Gilmartin’s success in exciting the interest of powerful investors in London and Dublin did not go unnoticed, and as the scale of his vision and plans became known among the financial and political elite it became apparent that there would be attempts to get a slice of the action or, failing that, to cause obstruction to his plans. When he sought to purchase a site in an affluent south Dublin suburb in 1986 a shocked Gilmartin was told by an agent that a leading financier would appreciate a tidy £75,000 under-the-table payment in exchange for closing the deal. Gilmartin made it clear that it was not the way he did business. In the event he did not proceed with the purchase, as he realised that it would be made unviable by the county council’s plan for a motorway through the site.

Arlington Securities, a public company that had successfully developed major retail projects in England, backed by a number of prestigious pension funds and other investment houses, was the first to declare a real interest in Dublin as an investment prospect. Ted Dadley, whom Gilmartin knew from a property venture in Wales and who had previously worked for the supermarket chain Tesco, had recently joined Arlington. Raymond Mould agreed to travel to Dublin to look at the Bachelor’s Walk site. Gilmartin had made sketches of the scheme, and by early 1987 a plan for a large shopping centre at Bachelor’s Walk was well under way. He was offered £250,000 by Arlington Securities, as well as the reimbursement of expenses and a percentage of the profits generated in the project.

The site was made up of derelict buildings, which pockmarked the quays, stretching back to Middle Abbey Street, most of which had lain idle for years. Almost all were unoccupied, though there were preservation orders on some of the Georgian houses, a few of which had retained their rich interiors. Like the north end of O’Connell Street, the area was in sore need of regeneration, and part of it had been included under the urban renewal incentive scheme of 1986, which offered tax incentives to anyone willing to invest.