Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Nick Hern Books

- Kategorie: Poesie und Drama

- Serie: NHB Modern Plays

- Sprache: Englisch

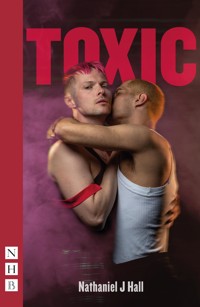

'This is the story of how we met, fell in love, and fucked it up. But it's not just our story. It's his, and his and theirs. Maybe it's yours…' Manchester, 2017. During a hot and sweaty queer warehouse party, two damaged hearts collide. He is HIV+ and drowning in shame. They are one microaggression away from a full-on meltdown. Together, they form a bond so tight, they might just survive it all. But sometimes survival means knowing when to leave. Pulling back the glittery curtain of pride to reveal the devastating impact of generational HIV stigma, racism, homophobia and repressive gender norms, Nathaniel J Hall's Toxic is a powerful, passionate play celebrating survival and the resilience of the queer spirit. Inspired by true events, it was first performed at HOME, Manchester, in 2023, before touring the UK in 2025, directed by Scott Le Crass, and performed by the playwright alongside Josh-Susan Enright. 'An intimate portrayal of queer love, aching with authenticity, pain and joy' Russell T Davies

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 86

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2025

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Nathaniel J Hall

TOXIC

NICK HERN BOOKS

London

www.nickhernbooks.co.uk

Contents

Introduction

Foreword

Acknowledgements

A Context

Original Production Details

Characters

Setting

Toxic

A Glossary

About the Author

Copyright and Performing Rights Information

IntroductionNathaniel J Hall

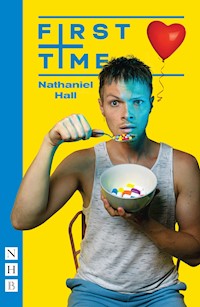

In 2017, after nearly fifteen years of living in secrecy and shame as HIV-positive (diagnosed at sixteen, after my first sexual encounter – talk about unlucky), I decided to break my silence. I wrote an emotional letter to my family, and then did what felt completely natural to me, a professional show-off, but a move that would horrify most other normal people: I turned my story into a one-person play called First Time.

Commissioned by Waterside Arts in South Manchester, I figured it would help me unload some of my emotional baggage and maybe give my sinking acting career a boost. If not, well, I’d wave my white flag with the sinking ship and slump off quietly to find a new career.

Much to my surprise, however, First Time struck a chord with people – big time. Buzzfeed News picked up the story, then BBC News, MTV, Radio 5 Live… I was even invited to the BBC Breakfast couch to chat with Charlie and Naga. A few weeks earlier, I’d only just told my parents about my HIV status. Now, I was trending higher than Jennifer Aniston’s bangs (I kid you not). Talk about zero to a hundred in just a few weeks.

Over the next four years, First Time was performed over a hundred times, including an award-winning run at the Edinburgh Festival Fringe, receiving both critical acclaim and audience admiration. It also sparked a powerful wave of HIV disclosures, with one person sharing they had lived in silence for thirty years before coming out publicly at a post-show discussion. These stories inspired me to create In Equal Parts, a community-led outreach project tackling HIV stigma and shame. To date the project has reached over seventy thousand people and continues to empower others with HIV to live boldly and without shame.

The success of First Time kept that impending career change at bay. I landed a role in It’s A Sin, Russell T Davies’ hit Channel 4 drama, and as the only openly HIV-positive actor in the cast, another whirlwind media frenzy ensued – one so big it required a spreadsheet to manage. (Shoutout to my partner Seán for being a total freak in the [spread] sheets.)

But despite all this public success, my personal life was still a mess. Drugs, risky and compulsive sex, alcohol – they were still plaguing my world. In 2019, I found myself trying to escape a deeply problematic, co-dependent and, at times, abusive relationship. And looking around at my community, I knew I wasn’t alone.

Many of my LGBTQ+ friends were stuck in similar toxic cycles of substance misuse, unhealthy relationships and risky sex. I dove into books like Straight Jacket by Matthew Todd and We Can Do Better Than This compiled by Amelia Abraham, cried my eyes out, and eventually started therapy – where I cried a whole swimming pool.

I began to realise that I’d been using alcohol, drugs and sex to mask the emotional pain caused by a world that had treated me badly, and when my own compounded trauma collided with someone else’s, well, it was a car crash waiting to happen.

Through creative workshops and research, I learned that many LGBTQ+ people – particularly those at the intersections of disability, race and gender non-conformity – carry additional layers of trauma. This discovery broke my heart, and I cried an ocean. I was left asking, ‘when the world treats us so horribly, why do we end up treating ourselves and each other so badly too?’

First Time had helped me reconcile the trauma of my early HIV diagnosis at sixteen, but now I felt like I’d sold a bit of a lie. Everything in the play was true (except for the holiday disco, which was actually karaoke – nobody wants to hear me screeching a rendition of ‘My Heart Will Go On’ night after night), but something didn’t feel quite right.

First Time was crafted as a ‘queer rags-to-riches’ story that often brought audiences to their feet in ovation. But there were no standing ovations in my personal life. After the high of the Edinburgh Fringe run, I had to leave my last relationship for my safety, sell all my possessions in a week, and move back in with my parents. Real life felt like a one-star review, not the five-star triumph I had portrayed on stage.

Then the global pandemic hit. Amid the chaos of those months, I had time to reflect on everything. I knew I needed to face my pain head-on – just like I had with First Time. That’s when Toxic was born.

Unlike First Time, Toxic is only semi-autobiographical. It weaves in stories from other LGBTQ+ people I met through workshops, touching on other issues including racism, class, sexuality and gender. As I wrote, I realised how deeply historical marginalisation and societal prejudice continue to affect queer relationships. Toxic explores how these ‘minority stressors’ show up in our intimate lives, often with devastating consequences.

Through the play, I also wanted to represent a broader spectrum of experiences. As a white writer, I was nervous about portraying a person of colour in a play about an abusive relationship, but the stories I heard from queer people of colour spoke so much truth to power that I couldn’t ignore them. At community script-sharing events for LGBTQ+ people of colour and their partners, early drafts were met with critique, especially around racial stereotypes I had stumbled into. I listened, leaned into the discomfort, and worked hard to do better. I’m forever grateful to those who helped me – particularly Susan Kerr – who challenged me with kindness and compassion.

Writing Toxic has been a deep, humbling lesson in unlearning, especially when it comes to racism. Tackling systemic inequality requires tough, uncomfortable conversations, and I’ve learned that dismantling these structures is the work of all of us – white, Black, brown, and every shade in between.

Toxic doesn’t end with a standing ovation like First Time. It’s not that it’s not good – I’ll let you be the judge of that. It’s just that it dares to sit with the messiness and complexity of life. It still has heart, hope and humour (I try to write serious drama, but everyone seems to laugh, and maybe that’s a good thing). In a way, Toxic is a love letter to all my exes and to myself, an apology for how things turned out, but also a thank-you for the life lessons learnt.

Ultimately, Toxic is a story of queer survival and resilience in the face of relentless societal prejudice and shame. I hope that when people read or watch the play, they laugh with us, cry with us, and, most importantly, reach deep inside themselves and say to their own wounded inner child, ‘I’ve got you, we’re going to be okay, we’ll survive this, together.’

* Medication taken pre-emptively before sex that is highly effective at stopping transmission.

** Research that proved people with HIV on effective mediation with an undetectable viral load can’t pass the virus on.

ForewordSusan Kerr

As a little Black girl, the brutality of the world terrified me, and I found myself desperate to understand why. I hoped that if I could grasp the root of hatred, I could somehow protect myself. This obsession with understanding became a passion, and in 1999 I qualified as a therapist.

Years later, as an older queer Black woman, I’ve witnessed first‑hand the shifts in the LGBTQ+ cultural scene. These shifts have shaped the club I co-run in South Manchester with Vicci Jones, called Stretford Wives. Our events focus on creating a space where connection and community thrive, because what life has taught me is that most of us long for these things.

I’ve always been captivated by storytelling and the power of drama, though I came to playwriting later than most. In 2021, I joined a short playwriting course with Dibby Theatre. Since then, I’ve written two short plays – Unapologetic and We See Each Other Better with Our Eyes Closed (the latter commissioned by the Greater Manchester LGBTQ Culture and Arts Fund). I’m currently working on my third play.

It was through the First Dibs playwriting course that I met Nathaniel and Dibby. When they invited me to support the development of Toxic, I was curious. Like many white-led organisations, they talked the talk on diversity, but would they really walk the walk? I’d been disappointed by whiteness before, but I walked toward them with an open heart, willing to give them a chance.

Racism says ‘Black is ugly’ without proof or right to defend itself, while offering whiteness endless praise. It’s an insidious force, and it’s why many Black and anti-racism activists are exhausted. A play can entertain, educate, or even transform, but representation aside, I believe the truth is more interesting. I was pleased to see that Nathaniel agreed.

The first draft of Toxic presented the white character as the hero/victim and the Black character as the villain. Nathaniel, a passionate activist and social-justice warrior, was committed to challenging these stereotypes, but this initial version still reflected the bias embedded in our society. Even someone deeply concerned with social justice can fall into tired tropes, but Nathaniel acknowledged this challenge head-on, which I deeply respected.

During a community read-through for people of colour and their partners, we