6,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Atlantic Books

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

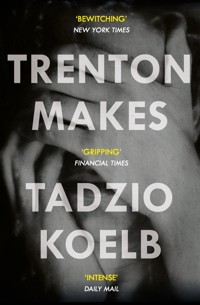

SHORTLISTED FOR THE CENTER FOR FICTION FIRST NOVEL PRIZE, 2018 __________________________________________ "A novel of bewitching ingenuity"New York Times "Electrifying" Lit Hub __________________________________________ Abe Kunstler wants his share of the American Dream, which for him is a factory job, a wife and a family. Getting these things will be harder for Abe than it is for other people, however, because his life is a lie - an invention forged in the heat of a terrible crime. Haunted by his past, terrified of exposure, and searching obsessively for redemption, Abe moves from one ruthless act to the next, tricking an alcoholic young taxi-dancer into becoming first his wife, then the mother of a child she believes is his. When the life they have built is threatened, he becomes desperate, until even Abe himself isn't sure how far he'll go to keep his secret...

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2018

Ähnliche

TRENTON MAKES

TRENTON MAKES

TADZIO KOELB

First published in the United States of America in 2018 by Doubleday, a division of Penguin Random House LLC.

First published in Great Britain in 2018 by Atlantic Books, an imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd.

Copyright © Tadzio Koelb, 2018

The moral right of Tadzio Koelb to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities, is entirely coincidental.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Hardback ISBN: 978 1 78649 406 1EBook ISBN: 978 1 78649 408 5

Printed in Great Britain

Atlantic BooksAn Imprint of Atlantic Books LtdOrmond House26–27 Boswell StreetLondonWC1N 3JZ

www.atlantic-books.co.uk

Although the characters and events described in this work are fictional, they are neither without precedent nor are they so rare as readers might believe.

Man is something that shall be overcome.What have you done to overcome him?

—FRIEDRICH NIETZSCHE,THUS SPAKE ZARATHUSTRA

part one

____________

1946–1952

“The new guy should come, too,” Jacks had said in his loud voice, flat as a hand clap, his barrel chest steeped and brimming with all his endless simplicity. Of course the plan had been there all along, but in a way it was Jacks who set the whole thing in motion, because Jacks had said Kunstler should come to the dance hall, and Kunstler had come. It was Jacks, too, who introduced Kunstler to the girl, the taxi dancer, the one called Inez Clay.

“I danced with her,” Jacks said, pointing out one girl after another as they swung by with their clients. “And her. And her, I danced with her lots.”

“That’s a lot of dimes, Jacks. It’s like you’ve danced with every girl in Trenton. No wonder you roll your own.” Kunstler’s little metallic rasp of a voice was hard to make out over the music, so Jacks had to bend to hear him ask, “What about that one?”

“Oh, that girl? Yeah, I danced with her. The guys say she’s got trouble. Kind of like a dipso, they said.”

Kunstler lit a cigarette and said, “Like a thing is a thing.”

“What?”

“Like a thing is a thing. Someone like a thief is a thief. Someone like a cutup is a cutup. And somebody like a dipso is definitely a dipso. Like just is, there’s no difference.”

“Yeah, well, she don’t go bitching around or anything, I don’t think. She just drinks a bit is all.” He lowered his voice and said, “Actually the other girls sometimes say that she’s kiki, because they figure maybe she don’t like men on account of she doesn’t like it when the guys get too, well . . . touchy. You know.”

“Oh, touchy. Sure, I know,” said Kunstler, who instead didn’t touch her, or at least not at first, except to shake her hand when Jacks introduced them, calling her “Miss Clay,” and later to put a hand on a place high on her back when they danced. Instead he bought her drinks and gave her tickets, which she would rip, turning away to tuck half in the top of her stocking, passing the other half seemingly without looking to a ticket-taker who simply appeared and vanished so quickly again into the crowd that he was little more ever than a reaching hand and a gesture, as if the beaverboard walls with their red-white-and-blue bunting had arms. Then during the band’s breaks Kunstler bought her a fresh drink every time and while she drank it they talked—about what, the others couldn’t imagine, but she laughed a lot, and when she danced with other clients it seemed that she and Abe Kunstler still found each other’s eyes.

The girl was small: that’s what caught Kunstler’s attention. He wouldn’t dance with a tall woman, wouldn’t be the little guy with his face buried in some bosom to be laughed at, so the sight of her, petite but not boyish, filling her rayon dress, was a relief. He watched her smile at a factory man still in his cheap war-time woolens and then draw him to the crowded floor, let him stand too close and reach gradually down her back. He also noted the almost invisible retreat by which she baffled his hands when the song was done, no refusal but an evaporation that was also a barrier. She was watery, effortlessly variable, not to be grabbed with fingers. Their first time on the dance floor Kunstler had offered her his right hand and she laughed. He pulled it away.

“Don’t be angry,” she said.

He nodded. “Mind if we stand—” he started, and she waited and then nodded and whispered, “Away from your friends? Sure.” She led him a little way across the hall.

“Now, watch,” she demonstrated, moving around him as if he were a spindle, operating his arms. “Open position, here, and now closed position. See? This is how to move for an arm lead. And this is how you move for a body lead.”

“Oh, fine,” he said. “I won’t remember that.”

“Don’t worry, the names don’t mean anything, it’s what you do that matters. You’ll get it, it’s no big deal. This one’s not too fast, it will be easy,” she said as they started to move away towards the floor. Even then Kunstler was aware how good they looked together, that her softness suited his sharp bones. The girl Inez said, “A few more kisses.”

Abe pulled his head back and said, “Sorry, what?”

“The song. ‘A Few More Kisses.’ I like it. Don’t you like it?”

“Sure,” he said, “it’s swell,” but he was concentrating hard on the raised left arm and his right hand at her back, the mirror image, the inverted world, and then they were done, and when her body was gone he was left with a sense he couldn’t quite name.

At the end of the night Kunstler waited, ready to help the girl when she stumbled a little drunkenly on the stairs outside the entrance. She asked if he would stop with her in a bar. “The booze at the hall is watered, you know. And I want to listen to some real music. That band’s terrible. Everything in that place is terrible. Don’t you just love music? I mean real music, good music. Not that stuff they play there.” He bought her a gin and Italian, and watched her carry the short brimming glass cautiously to a booth, where she sat without her shoes and sculpting her arches with both hands, saying, “You’re never off the clock in those dumps. If you want to even think, you’d better goddamn hop it. They run you sore. You know when we haven’t got a fellow we’re supposed to dance with each other? Like I’d spend a minute longer with one of those girls than I have to.” They sat quietly for a minute, Kunstler neither moving nor speaking, just watching her through the bar darkness with his cast-iron expression. Inez finally said, “Hey, I noticed you work with mostly a lot of Micks. Are you a Catholic?”

“What, me? Oh, hell, I don’t know. Maybe. I’m not what I am any more, whatever it is.”

“Not a church person, you mean? Me neither.” She nodded at that and took a drink before nodding again as if her head rested on the ocean, and said, “I’m Episcopalian. I guess I mean that my mother was.”

Then she spoke almost unstoppably, a surge of memories about foster homes where she experienced some things too soon and in overabundance and others not enough. The girl had been fifteen when she accepted her first ticket to dance with a boyish enlisted man at one of the halls near Mountain Home. Both of them had been careful and shy. Back then she drank only Coke and bitters, but of course it was a dance hall, and really they sold two things: the one was illusion, the make-believe of intimacy and gaiety and carelessness. The other was alcohol, which dressed the stage where the illusion could perform. “The pop hurt my stomach after a while,” she told him. “Can you believe it, that I had my first cocktail for my health? I always crossed my ankles back then, too. Well, hey, that’s life. I mean, what are you going to do?”

It was in Mountain Home that she met the young Brylcreemed piano player she had followed east. “He was called Boat,” the girl said, “on account of he had huge feet, really big. I mean it. He could hardly find anything to fit them. This drummer once said Boat was wrong, he could buy any old shoes and it didn’t matter what size, just to wear the box they come in. Isn’t that funny?” she asked without laughing. She also described the girl singer they had met at a show in the taxi hall at Millville, a girl whose stockings weren’t full of blisters, a girl Boat finally left with, taking with him all the money from the motel room, including all the hard-won nickels that were her fifty percent share of the dimes men paid to dance. “It was mine as much as his, you know. I had to start again, and I’ll tell you, it’s not easy to save up money at five cents a dance. Someone saw them get in a cab, that’s all. That’s how I knew they were gone.” She looked up at Kunstler, and leaning against him, asked, “Do you think it’s because I like spooning more than I like the other stuff? It’s not that I don’t want to be more like that, more like what it was he hoped for. More what I suppose all men hope for? But things are what they are, I guess. Ever have too much ice cream when you were a kid? A man who was friends with my mother, it was like that with him. The worst part was he made me call him Uncle Andrew.”

When at last she relaxed into her gin haze and was quiet Kunstler led her gently to his rooming house, where he checked that the landlord wasn’t awake to see him taking her up the stairs.

Jacks had said to them, “The new guy should come, too,” and at just that moment everyone, even the ones who might have wanted to argue with him, realized Kunstler was standing right there, the first dressed as usual, silent but at hand, one eye closed against the smoke of his cigarette. Loitering, they called it. He stood with his tie knotted tight, one shoulder against his locker door, and nodded his bony face at them as if accepting a compliment, perhaps unaware that they, still open collared or in their undershirts and with their boots next to them on the benches and their socks in their fists, would later agree among themselves that it had been the little man’s idea in the first place. “The mouth may be all the way up there where Jacks keeps his head,” said Blackie, “but the brain. That’s lots closer to the ground, if you know what I mean.”

“You’re just angry about how he stumps your stupid pranks,” Ahern said, and it was true that Kunstler had frustrated them with his imperviousness. Olive pits and sandwich ends and chicken bones and other detritus from their various lunches left in his coverall pockets had been tossed aside so casually you might have thought he generally kept that kind of thing there himself. Blackie and two of the other die men had been especially furious at Kunstler for getting in the way of some practical jokes they played on Jacks, who was mocked for being cheap because he still rolled his own—although of course they knew without having to ask that he didn’t make much being only the janitor—and for having not been sent farther than North Carolina during the war, as if he had asked for the posting, or indeed had ever asked in all his life for practically anything.

And yet it wasn’t what Kunstler did but the way he had done it that left Blackie so sore. Everything with him went too far, somehow, and without ever being in any way a threat, still it was sinister, like a superstition you know is foolish but frightens you anyway: black cats or thirteen to dinner, an umbrella opened indoors. The first time had been the strangest, when around New Year Blackie, Simmons, and Breen had come back from a weekend skiing, still breathless and hectic, talking and joking, calling to one another over the rhythmic cry of the wire unspooling from coil to capstan to coil. At the lunch hour they had quieted suddenly to watch Jacks walk to the lockers and rummage in his jacket for cigarette papers. He thought to look before he started rolling only because of how they stood—clustered, alert—and having tumbled to them he held his paper up to the blunt electric light and saw someone had drawn a long and knotted penis, which he would then have put in his mouth.

“How do you like it?” one of them asked him. “Balls first or tip first?”

“Remember you have to lick it to make it sticky,” said Blackie.

Jacks crumpled the thin strip into his coverall pocket straight away, nodding around with a half smile and saying, “Okay, okay,” in his flush monotone. He pulled out another paper—only that, too, was part of the gag, because he had almost shaken out his tobacco before he noticed it was the same. In fact, as he peeled away one after another he found all the papers were ruined: they had drawn the same thing on every one and placed them carefully back in the box. Blackie and the others laughed out loud now. “That took us all weekend,” Breen said. “You should appreciate the hard work.” The emphasized word hard made them laugh again.

“How am I going to smoke?”

“You’re just going to have to chew that over.”

“Har, har. Come on, give me a cig.”

“Sorry, Jackson. I think we’re all out.”

It was then that Kunstler had appeared suddenly from his leaning place against the wall, and taking the little cardboard envelope from Jacks stood for a moment looking at it, flipping through the papers with all the lack of interest or hurry of someone looking through a book in a foreign language. “That’s funny,” the little man said in his high, croaking metal wheeze, a voice that always sounded as if it were being cranked out on a rusty machine. Then, still holding the papers, he said with the same absolutely humorless manner, the same patina of calm, “Hey, here’s a funny one for you. These three guys, they go skiing, but they’re just factory slobs, like us, no money. So they share a room, the three of them. Then there’s just the one bed, but that’s no problem, they can share that, too. Fine. And in the morning, the one on the left says, ‘It’s crazy, I dreamed some guy was whacking me off,’ and the guy on the right says, ‘Hey, I had the same dream.’ ” While Kunstler spoke he let the papers drop snow-like to the floor and offered Jacks a pre-rolled from his coverall pocket. He went on, Jacks leaning down expectantly, the others already gathering their anger. “So the guy in the middle, he says, ‘You two are nuts. I just dreamed I was skiing.’ ” Unsmiling, he lit a match against the wall, barely raising it to Jacks’ dipped cigarette.

“Jesus, that crazy bastard,” Blackie had said when it became clear Kunstler was going to let the thing burn right down to his fingernail. Jacks had been laughing too hard; he hadn’t noticed.

“Hey, tell us another one,” said Jacks, his cigarette still unlit in his hand.

“Maybe later,” Kunstler said. He dropped the burnt-out match and walked away.

When the whistle had gone, Kunstler, his thumbnail blistered a screaming painful black from the match, stood by the exit with his hands lost in his pockets, and didn’t move or even look around as the others passed him; he was waiting for Jacks the way a man waits for a bus, and waiting for Jacks to say, “Hey, do you want to go for a drink?” so that Kunstler, lighting a cigarette and handing one to Jacks, reaffirming their private currency, could say, “I guess so,” and follow to a bar. They went to a place not too far from the factory, a narrow alley of dark wood and tin panels that had been painted until their patterns were almost lost. The place had no stools. Men stood here and drank, and if they were too tired to stand, they went home. It was busy after the shift, and at the counter they waited a while for the bartender. Jacks strained his neck the whole time looking for whoever else they might know.

“ ‘I dreamed I was skiing,’ ” said Jacks. “That’s a good one. It took me a minute. I guess maybe you know a lot of them like that.”

“I guess. All of them, some of them. I don’t know. A few.”

“I guess Blackie seemed pretty sore that you got the big laugh, when he thought it was him would be needling me.”

“Well, he was falling anyway. I just pushed because I could.”

“How do you mean?”

“Nothing, forget it.”

“Hey, order me a whiskey,” Jacks told Kunstler, and walked a few steps away to look around.

When the barman came Kunstler held up two fingers and said, “Whiskey.”

“Water, soda?” said the barman. Kunstler felt blank, but steadily looked at him across the counter. He took his hand out of his pocket and put it carefully on the bar’s scuffed wooden edge, dollar ready between forefinger and thumb, but the barman simply repeated himself, only louder, the words knuckled, “Mister, straight, water, or soda?” and waited. “Right,” Kunstler said without expression, but found the barman still didn’t move, and so added, “Soda.” The barman went away. When the drinks arrived Jacks returned to the bar, where he paid by tossing his dollar bill at the counter, and then Kunstler tossed his, too, so that it landed almost on the first and was immediately caught and taken by the barman and replaced with coins. Holding their glasses Kunstler and Jacks stood with their backs against the zinc-topped bar and looked at the grey winter light coming through the half-glass door. The big man’s flushed face shook and nodded to the sound of the radio but Kunstler barely moved his head at all; only his eyes turned as the other drank, their movement hard and hidden, and when Jacks had taken a sip and not complained or made a face but simply kept up a gentle springing to the rhythm, Kunstler drank, and to himself repeated: Soda. Whiskey and soda. Soda. He bought the next two rounds. Jacks said, “Hey, you buying me all these drinks. Thanks,” and Kunstler answered, “Hell, it never hurts to be friends with the big guy.”

“I’m sure big,” Jacks said in his unmodulated yell, standing up and puffing out his chest. Kunstler laughed—a light tipsy fluting—but stopped right away.

It wasn’t the first time Kunstler had drunk too much, but it had been a long while—too long, he decided, since like everything it was a skill—and then it had been different before, when it wasn’t him yet, and someone else had been there to steer the blinded ship, then later share the pain. When he woke up the blurred clock read nearly five-fifteen. The way he felt, he wasn’t sure he’d wound it. The only way he even knew for sure he had gone to bed was because that’s where he woke up. He experienced a moment of terrible panic: he tried to remember what he had done. Had he said something he shouldn’t? He still had his shirt on. That reassured him, somehow. His thumb ached with burning.

In the bathroom on the landing the key was turned as carefully as ever in the lock, but otherwise it was all a rush: he dumped his razor and mug and brush in the yellowed bowl, and while he dressed he ran the tap so they all got good and wet. He lathered just enough cream out of the mug to tuck some with his fingertip behind his left ear. As he was about to turn the key again to leave he realized he had made a mistake. With his hands he wet the towel, too—in the middle, and taking care not to over-do it. Consistency and details: these were the things that kept him safe. A clean-shaven man must have his elements—a foamy brush, a wet razor; on the peg he leaves a humid towel just as surely as a passing car leaves tracks in snow. Kunstler let the door slam behind him as he went down the stairs two at a time.

In his street he just walked—quickly but not too quickly, because to rush, he knew, was to invite attention, recollection, investigation—until he turned a corner and the boardinghouse was out of sight; then he ran through the hunched, aluminum-sided streets. He ran all the way to the grassy strip that edged the train tracks, and after looking to see that no one was there to observe him in the growing light, ran on and over the short hill. Stumbling up the embankment muddied his knees, and for a moment it felt as if the edge of the fence where he ducked under might have ripped his jacket. He didn’t wait, though, as this was the only chance he had before work started, and in a moment it would arrive, and a moment later be gone, even if it felt like forever while the noise of it was in his chest, and he knew that consistency was everything, had learned once from a door heart-stoppingly ajar to a diner men’s room that nothing could be forgotten, not for a day or an hour, not even for just a minute, because the world was an eye that never blinked. He must be the same in all things: unvaried in his voice, just as in his walk or his clothes. Nothing can change. The sound was coming already as he slid down to the tracks where the grass seemingly trembled in anticipation of the approaching wind. He bent with his hands on his knees to catch the breath he had spent on running. Then with all of a machine’s thundering furious uniformity of sound and motion the Pennsy rushed past, drowning everything, and while it was there, the shattering storm of it all around him, he screamed as loud as he could, arms seized to his sides by effort, lost in the godly mechanical noise until the muscles of his face and throat and chest burned and recoiled and refused to scream any more. Then the train was gone and the wind and passion with it; there was emptiness and silence in its place. He found his hat ten yards away. Later he threw up his first cup of coffee and it smelled like booze.

He had worked other jobs at first—menial, small, unskilled, and uninteresting. He had been testing, trying, but especially learning from the men, the Greek waiters and the colored busboys, the customers who ate every day sitting on vinyl stools at plastic counters without speaking or removing their hats, who told dirty jokes and drank their coffee while they chewed, who threw their ties over their shoulders when they had soup and carried the paper in their suit pockets. Their badges were crusts of dried shaving soap and hair oil and bluntness and the endless scratching between their legs. He watched them, cautiously but closely, especially the occasional ones who showed up still in uniform, making their way back from France or the Philippines or wherever the war had taken them, eating and drinking and dancing up their last few weeks of service pay ten cents at a time with the irrepressible cheer of men taken off guard at coming home alive.

Despite the fears that shook him, no one back then had ever asked him for anything except his name. Saying it the first time out loud drove an edgeless hole of panic through his chest. He had been repeating it to himself every waking hour for days, said nothing else to anyone, a prayer to a lost god that he had begun reciting the minute he saw the handwritten advertisement in the diner window, help Wanted, and repeated endlessly, chant-like, in a frenzy of postponement. It was hunger that had driven him back to the diner as if at the point of a knife. He was almost disappointed to find the card still in the window: it meant he had been cursed with luck and would have to go ahead with his plan, see it through. He would not that easily escape the accident that defined him.