Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Merlin Unwin Books

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

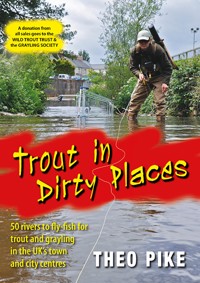

Here is a guide to the most revolutionary development in British angling for many years: fly-fishing for trout and grayling in the very centre of towns and cities throughout the United Kingdom. From Sheffield to South London, from Merthyr Tydfil to Edinburgh, this is the cutting edge of 21st century fishing. Nothing is more surreal yet exhilarating than casting a fly for iconic clean-water species in the historic surroundings of our most damaged riverscapes – centres of post-industrial decay, but now also of rediscovery and regeneration. * fishing-focused profiles of 50 selected streams * interviews with local conservationists dedicated to restoring the urban rivers * local flies and emerging traditions, and * details of how to get involved and support this restoration work. This book guides readers towards relaxing, good-value fishing on their own doorsteps as a viable alternative to more costly (and carbon-intensive) destination angling: a positive lifestyle choice in challenging moral and economic times. No one author or publisher has yet attempted to bring this emerging trend of urban flyfishing into a single, epoch-making volume. **A donation from all sales goes to the Wild Trout Trust and the Grayling Society **

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 391

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2015

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

To my parents Theo and Jean-Marie who first told me to go fishing, and to my wife Sally who still says the same.

CONTENTS

FOREWORD

Charles Rangeley-Wilson

I’ve thought a lot about why fishing for wild trout in a city should be so compelling. On one level there is the simple thrill of casting a line within sight of office blocks, planes overhead, trains rattling by: all that clatter and rush and you, the still point at its centre, tuning in to a slower, deeper rhythm of water and wild spaces.

Fishing brings you to a different place in more ways than one and if you can get there on the way home or in the lunch hour, then the pleasure, for being stolen or endlessly surprising – and the sight of a brown trout rising to mayflies in a city stream really is endlessly surprising – will be so much the richer. But underlying and resonating with this thrill is the wonder of finding something emblematic of wildness in the midst of its very opposite. There is Romance in that, in the thought that Nature can overcome, or at the very least co-exist. And if one way of accessing that Romance and the sense of hope that springs from it is with a fishing rod in hand, wet waders sploshing along a busy High Street, then why not?

As Theo’s fascinating, celebratory book reveals, rivers and fish lost to generations of anglers – the once-wild rivers on the fringes of cities that have now grown to engulf them and the stunning, fabled trout that held on in spite of that encroachment until finally they gave in to tides of filthy water – are there again, for the first time in a century or more. Clean rivers and wild trout in the city!

City fishing for wild trout is – as well as being left-field, exotic on the doorstep, adventurous in the best sense, cheap and very cheerful – a wonderful affirmation of hope, a declaration that Nature can overcome and that we can build a world where there is room for both people and the wild.

Go to it.

INTRODUCTION

Fly-fishing the urban wilderness

For adventurous fly-fishers at the start of the twenty-first century, it’s easy to get the impression that there are no new waters left to discover.

Less than eighty years after Negley Farson fished his way across Chilean Patagonia with companions who thought the rivers were getting too crowded if another angler appeared within ten miles, Planet Earth already feels like a much smaller place. Cheap flights and plentiful leisure time have brought the world’s furthest-flung waters within easy reach, and the new media revolution makes even the most exotic destinations feel familiar and a little too well trodden.

Steelhead in British Columbia? Seen it on DVD. Mahseer in the Himalayas? All over the internet. Taimen in Mongolia? Wasn’t somebody video-blogging that last week?

But as you’re about to discover, fly-fishing’s most fulfilling new frontier may be no further than the urban river at the end of your street. And there’s nothing more inspiring and counterintuitive than casting a fly for iconic clean-water species like trout and grayling in the post-industrial surroundings of some of our most damaged riverscapes.

The world’s first industrial revolution – and Britain’s biggest conurbations – were powered by water flowing swiftly over Jurassic and Carboniferous geology, rich with deposits of coal, iron ore and limestone. Rivers naturally aggregate their catchments’ features, so these steeply-falling streams paid the price for landscape-scale industrialisation: impounded and dewatered for power and industrial processes, then converted into open drains to carry away every possible form of human and manufacturing effluent. Many rivers literally died at this point: scoured by floods of toxic waste, superheated by power stations and steel mills, hemmed in with vertical walls, even culverted completely when they overflowed with filth and became too much of a risk to human health.

Almost without exception, industrial rivers started out as their towns’ defining features, but the economics of exploitation turned them into dangerously uncontrollable forces of nature that had to be subdued at almost any cost. Modern river restorationists recognise three distinct stages in our historic attitudes to urban waterways. From around 1850 to 1950, rivers were used for sanitation, waste disposal, and sometimes transport. Between 1950 and the 1990s, sewage treatment and pollution control improved dramatically thanks to the privatisation of the water companies, the creation of the National Rivers Authority, and finally the abrupt decline of Britain’s heavy industries: a tragedy for many communities, but an unexpected blessing for the rivers.

Finally, in the early 1990s, a few radical thinkers returned to the realisation that waterways weren’t just drains and sources of disease, but positive assets that could once again improve our lives and lift our spirits: the same pioneering philosophy that drives so many of the people and organisations you’ll meet in these pages. (Today the upward trajectory of river restoration across Europe has been made legally binding by the EU’s Water Framework Directive, complete with targets for the UK’s Environment Agency to deliver in the form of river basin management plans by deadlines in 2015, 2021 and beyond. Classed as ‘heavily modified water bodies’, many of our urban rivers will probably be restricted to targets of ‘good ecological potential’ rather than the optimum ‘good ecological status’… but it’s a start).

All this time, relict populations of wild native trout and occasionally grayling had been holding out in headwaters and other refuges on the fringes of industry: now they started dropping downstream again, often as unnoticed as the recovering rivers themselves, to recolonise reaches that hadn’t seen an adipose fin for generations.

Trout can stand small amounts of organic pollution, but grayling tolerate only the cleanest water, so their presence is an excellent indicator of the highest chemical and biological water quality. Like the knotgrass, docks and rosebay willowherb which reclaimed the barren stony landscapes left by the last Ice Age, salmonids of all species are natural early-adopters, and they’re surreally suited to life amongst the decaying human infrastructure of postindustrial rivers. In these urban ecosystems, collapsing blockstone weirs provide oxygenation and pocket-water habitat. High walls and overhanging gantries give shade on the hottest days, and spawning can take place in plumes of gravel behind main-channel boulders, or on gravel ramps kicked up by the scour pools of major weirs if tributaries are blocked.

By the time urban trout reach maturity, they’re hardened survivors, tender yet tough, streetwise to short-lived slugs of pollution, and capable of clinging onto life under the most adverse circumstances. In and around our towns and cities, I’ve gradually come to realise, there may very well be more water with trout than without.

But despite their recovery and fragile resilience, we shouldn’t be in any doubt that urban trout and grayling still inhabit rivers on a knife edge. Chances are, between the time I finish writing this book and you start reading it, at least one of the fisheries I’ve selected as a snapshot of urban river restoration at the start of the twenty-first century will have been wiped out by pollution. Maybe this incident will be right in your face, a matter of public scandal like Thames Water’s spillage of bleach into my own River Wandle in London, or Grosvenor Chemicals’ fire on Slaithwaite’s River Colne. But just as often, it may be as silent and insidious as the insecticides which leached from a wood yard at the top of the Rhymney River in the south Wales coalfield, killing fishfood invertebrates for miles downstream, undetectable without months of patient, determined detective work.

Besides the occasional catastrophe that headlines the national news, urban rivers face a whole suite of everyday problems, many of which you’ll encounter as a fly-fisher exploring these ambivalent places. Every town offers countless sources of diffuse pollution, from dark grey fine-particulate road-dust that settles behind weirs and behaves more like water than ordinary mud, to iron-rich minewater seeping from long-abandoned tunnels and drainage adits. That ozone tang in the air probably suggests treated sewage effluent, contributed day and night by your fellow citizens, while rags trailing on brambles and low-hanging twigs betray sewer misconnections or Victorian-era combined sewage and stormwater outfalls which overflow in times of heavy rain. Sheet-steel revetments and concrete walls have often been installed as bunds to isolate the river from industrial waste permeating the soil and groundwater, and it’s a rare dry-cleaning business that doesn’t leave a legacy of land contaminated by chlorinated solvents. And then of course there’s fly-tipping: in the words of Brian Clarke, ‘anything that can be picked up, carried and dropped, you’ll find it in an urban river’.

But as Stuart Crofts also points out whenever we’re stalking grayling on his native River Don in Sheffield, salmonids love stability, and that’s exactly what postindustrial rivers offer them: conditions which will undoubtedly have helped some populations improve even in the months since I visited and photographed their gritty urban environments. And the fact that these beautiful pollution-sensitive fish are here in the first place isn’t always coincidental, or simply a citified variation on Christopher Camuto’s whimsical compression that, ‘roughly speaking, if you rub a mountain with cold, flowing water, you get a trout’.

All over Britain, soon after the benefits of better sewage treatment began to bite, people started regarding their local rivers in a fresh light. Inspired by forward-thinking organisations like the Wild Trout Trust and the Grayling Society, they looked for new frontiers in fishing and river restoration, and found them hiding in plain sight: under culverts, through industrial estates, and along the sprawling edges of big-box supermarket car parks where derelict mills recently stood.

Many of the people I’ve profiled got started in river restoration just like I did: driven by quixotic curiosity to follow ill-reputed urban streams wherever they led, slowly falling under the spell of their unloved currents, forming alliances with other wet-wellied pioneers, clearing decades of fly-tipped rubbish, and gradually taking responsibility for restoring water quality and habitat in whole river reaches and even catchments.

And inspiration flowed both ways. In 2008, enthused by the achievements of small voluntary groups on the Wandle and Colne Water in particular, the Wild Trout Trust launched its Trout in the Town programme: a support structure for anyone who wanted to see iconic wild trout making a comeback to their own part of the inner city. In various stages of development, Trout in the Town chapters already bracket Britain from London to Glasgow.

For all its international leadership in hands-on habitat improvement, I like to think the Wild Trout Trust does its best work by giving small groups of volunteers the expertise and confidence they need to champion positive views of unsung rivers to the statutory authorities and other more established wildlife organisations – some of which may never have considered the river as part of their conservation plans. Armed with knowledge and the right set of circumstances, these grassroots initiatives can grow all the way up to full-blown Rivers Trust status, officially recognised as project partners by government, its agencies and other third-sector bodies alike. (According to their own figures, Rivers Trusts are probably the fastest growing environmental movement in the world today, having expanded from five founding Trusts in 2004 to more than forty in 2011, covering more than eighty per cent of the UK’s total acreage of land and water).

As Rivers Trusts, Trout in the Town chapters, independent local river care groups or angling clubs, all the voluntary organisations looking after our urban rivers are founded on deeply democratic and charitable principles, relying on voluntary involvement and consensual partnerships to generate surprising levels of social cohesion, and get local communities involved in caring for their rivers.

Over the last decade, river restoration in the UK has ridden a strong current of social and philosophical as well as environmental change, embodied in a deepening conviction that these unloved urban places, once heedlessly trampled in the rush to be elsewhere, have become the responsibility of everyone with the vision to appreciate their scarred and paradoxical beauty.

And why not? Recent studies in the field of ecosystem services have valued the health benefits of living close to green space in urban areas at £300 per year for the average person: probably more for anglers who don’t just look at their surroundings but get actively immersed in them. Our new urban fisheries are a precious common resource, and from this angle it’s logical to think of post-industrial river fishing as a positive ethical choice in challenging moral and economic times. Low cost, low carbon, low time commitment: this is where you can relax and get your fishing fix while your other half goes shopping, with no worries about lost rods, jet lag and all the paraphernalia and nagging guilt of high-flown destination angling. Crowds will probably stare and point from bridges, but you’ve already slipped through a portal into a parallel world, where shoals of grayling hover beside traffic cones and shopping trolleys, and trophy trout sip dry flies in the shadow of crumbling mill walls a hundred years older than America.

Naturally, there’s a balance to strike. For months before starting to write this book, I thought long and hard about the dangers of hotspotting: the risks of exposing vulnerable recovering rivers to public attention, and putting too much pressure on fragile populations of fish. But on the whole I believe it’s better for an urban river to be known about and cared for – by the people and for the people – than overlooked, undervalued and repeatedly destroyed by pollution or simple ignorance. Then, if the worst does happen, we’ll know what’s been lost for a second time, and take savage steps to replace it properly.

So now it’s over to you. Throughout these pages, I’ve tried to avoid giving too many detailed directions: partly to protect the rivers from too much casual pressure, partly to heighten your own sense of exploration and discovery in a post-industrial wilderness as unique as the hills of Assynt, Patagonia or the Kola Peninsula. This is truly a foreign country in your own backyard, a place where you can combine outstanding wild fishing with the deep satisfaction of getting involved in improving the ecosystem you live in. It’s the cutting edge of twenty-first century fly-fishing, and the wild trout and grayling are closer than you think.

SOUTH WEST

Urban fishing starts here: on the edge of Okehampton, the West Okement tumbles over a series of natural rock weirs

1

OKEHAMPTON

Rivers East and West Okement

The last week of August 1976 finally brought an end to England’s hottest summer since records began. For 45 days, most of the south west had sweltered without a drop of rain: reservoirs were pans of baking mud, and people collected water from standpipes on the streets.

Finally, on the bank holiday weekend, the drought broke over north Dartmoor with a huge cloudburst and floods flashing down the faces of Meldon Quarry into an acre of rock chippings near the West Okement. A torrent of acid stone dust, magnesium, iron and arsenic rushed down the river towards Okehampton, killing almost every fish and insect as far as the Torridge: a distance of 14 miles. But the perfect storm that probably changed the Okement’s trout fishery forever had already been brewing for years.

In 1970, four miles above Okehampton, construction started on the 132ft, 70-acre Meldon Dam: just one of several designed to take advantage of Dartmoor’s self-generated microclimate and yearly rainfall of more than 80 inches. Two years later, the penstocks were closed, the reservoir started filling, and the compensation flow for the West Okement was fixed at 7.7 megalitres per day.

With its average flow reduced by three-quarters, the West Okement was already under serious stress by the time of the drought, and it’s estimated that fish and invertebrates in this sort of naturally-acidic upland system would have taken at least seven years to recover from an incident like August 1976. But the likelihood is that they never got that chance – and ironically for all the best reasons. In 1981 a salmon pass was opened on the weir at Monkokehampton, and that winter’s record run took full advantage: ‘Fish up every ditch’, wrote Poet Laureate Ted Hughes for Anne Voss Bark’s anthology West Country Fly Fishing, ‘and salmon seen spawning within the town of Okehampton, probably for the first time in hundreds of years’.

This may have been the final twist for the trout of the Okement, previously numerous enough to be recorded in catch reports of four to eight dozen, including occasional trophies up to a pound. Recent observations by the Riverfly Partnership’s Dai Roberts on the Rhymney suggest that if invertebrate populations are weakened by other factors, voracious salmon parr can send a river’s ecosystem into a negative feedback loop that never allows it to recover: without significant caddis predation on salmon eggs, more eggs survive, and more salmon fry and parr predate in turn on the remaining invertebrates. Much research still needs to be done, but it’s a narrative that seems to fit the Okement perfectly.

At East Bridge, high walls and old mill buildings reflect the river’s industrial history

“Of course the river’s changed,” says another local angler gloomily, peering over the West Bridge as a passing shower spatters on the windscreens of passing cars and flecks the beery surface of the pool below us. “Now the weir’s gone down at Monkokehampton, it’s full of migratory fish. I had a five-pound trout taken to the taxidermist forty years ago, it was nothing to catch fifty trout of ten or twelve inches each. Old Ted Walsh the barber – he’d have a hundred a day on the wet fly. You couldn’t do that now.”

But the East and West Okements still carve quietly down through the town in parallel sandstone clefts to converge in a sprawl of supermarket car parks, and it’s cheering to see that even massive abstraction, quarry pollution and the town’s own history of industry and fishing pressure can’t eradicate the trout that splash in the foam lines. Domesday Book listed just one mill at Okehampton: in 1894 the Comprehensive Gazetteer of England and Wales recorded joinery works, three flour mills and a large cattle market that fed a noxious complex of tanneries, boot factories, and bone-crushing plants on both branches of the river. Until its pipe broke, the chemical fertiliser works on the East Okement pumped sulphuric acid up the hill to the station, and the Old Mill still stands empty, awaiting redevelopment, with a little wild brownie loitering under its concrete footbridge.

It’s also cheering to chat to my guide for the day, and hear how these rivers are being cherished again. Paul Cole is a local fisherman, farmer and volunteer for the Okement Rivers Improvement Group: a small, highly-motivated charity founded by the Mayor of Okehampton before she moved on to even higher office as chair of Devon County Council. On this last Saturday morning of the month, Christine Marsh is back in her element, organising more than 15 volunteers to clear litter and generally make the river more appealing and accessible for Okehampton residents.

As Paul and I watch chainsaw gangs coppicing trees on a near-vertical slope above ancient mine drainage adits, I’m starting to understand how the area’s most ancient rock formations are still influencing the river. “Here in Okehampton,” he explains, “we’re on the very edge of Dartmoor, which is really one vast bulge of volcanic rock that took three million years to solidify. The granite was capped before it could cool completely, so metals like tin, copper and lead were deposited according to how long they took to crystallise in fissures and hydrothermal vents.

Watching for a rise: Alan Biggs’ bronze statue of a little boy fishing at West Bridge

“That’s why you find tin mines on seams in the middle of the moor, copper a bit further out, and lead out here on the edges. The heat of the magma also cooked some of the older surrounding rocks, which gave Meldon Quarry its amazing mixture of metamorphic deposits. Overall, it’s a very acid geology: the river naturally comes off the moor at a low pH, and we often get minewater flowing out of the old adits in wet winters.”

Catch ’em young: Ethan Drewe collects litter during an Okement Rivers Improvement Group river clean-up

Since 2000, when the ORIG’s first major initiative rebuilt a public footbridge washed away in 1952, Christine and her team have successfully completely several other landmark schemes along the rivers. From a fisherman’s point of view, their work at West Bridge is most striking: repairing the weir and fish pass, filling in a derelict leat, clearing Japanese knotweed, and finally commissioning local sculptor Alan Biggs to create a statue of a little boy fishing, to draw the eye away from a big black sewage pipe. A few hundred yards downstream, at the confluence of the rivers behind those supermarket car parks, another long-term project culminated in May 2010 with the ceremonial opening of a wooden viewing platform backed with symbolic Y-shaped picnic benches carved from local cedar, and a bronze deer and fawn nestling in the undergrowth.

At the time of writing, ORIG has raised more than £80,000 from a combination of Natural England’s Aggregate Levy Sustainability Fund linked to Knowle and Meldon quarries, together with match funding and community grants from the District Council and other partners. “Our latest funders have been the Big Lottery under their Groundworks umbrella,” Christine tells me, “but they’re not so easy to deal with, lots of paperwork and hoops to jump through.

Caddis crazy: a wild trout from the West Okement

“The hard part is finding a funder for environmental work: then you hold onto them and try to keep them on board while you get Environment Agency permissions and other match funding in place. But because of our success rate and contacts, when the end of year budgets come near, it’s also in some partners’ interests to get rid of that odd one or two thousand pounds of underspend, or it will be reflected in their own allocation grant for the coming year. A little voluntary group like ours can always use that little bit of money to make a path, plant or coppice a tree, or hire a contractor at short notice. Job done!”

No way down: the West Okement from Okehampton’s supermarket car park

Okehampton: Rivers East and West Okement

Who’s looking after the rivers?

The Okement Rivers Improvement Group was founded in 2000 to protect and enhance Okehampton’s rivers and riverside environment for the benefit of the local community and visitors.

Registered as a charity in 2006, the group organises rubbish clearances on the last Saturday of every month, and raises funds for future enhancement projects. For the latest information, search online for the Okement Rivers Improvement Group.

Getting there

Okehampton lost its regular passenger trains in 1972, but a summer Sunday service returned in 1997 and may be extended in future. There are several supermarket car parks adjacent to the East and West Okement confluence, with parking for Old Town Park near Okehampton Castle, EX20 1JA.

Maps of Okehampton are available from the Tourist Information Centre in the Okehampton Museum Yard: OS Explorer 113 is also recommended.

Seasons and permits

Brown trout season runs from 15 March to 30 September; salmon from 1 March to 30 Sept.

Trout can be seen rising through the town, and locals do fish for them, but despite the statue of the little boy fishing at West Bridge, Okehampton Town Council isn’t keen to promote fishing in the deeply-incised river gorges for health and safety reasons.

Instead, West Devon Borough Council allows fishing on the West Okement in Old Town Park opposite Okehampton Castle with a valid EA rod licence: about a quarter of a mile from the first white cottage on Castle Lane up to the Okehampton golf course fence. Please leave your details at the West Devon Borough Council Okehampton Customer Services Centre on St James Street, EX20 1DH in return for a free permit.

Fishing tips

Today’s Okement wild trout are small but feisty, measuring from 4 to 10 inches.

A rod of 7 to 8 ft is ideal, rated for a 1 to 4 weight line. Local fly-fishers like Paul Cole use very small nymphs in early season, switch to shrimp imitations until the end of May, and then often fish dry flies until the end of September. Black Gnats are essential, with extra hackle for reliable flotation, and small Klinkhamers imitate a wide range of sedges and other naturals.

Mike Weaver’s Sparkle Caddis was originally tied for the Teign, but proves equally useful on many other Devon rivers: a classic modern fly pattern from a local master (and founding father of the Wild Trout Trust).

Don’t miss

• The Okement Rivers Improvement Group’s viewing platform at the confluence of the East and West Okement

• English Heritage’s Okehampton Castle: a romantic ruin painted by JMW Turner

• Meldon Dam: 4 miles above Okehampton, free moorland stillwater fishing with a valid EA rod licence

In Taunton’s eastern edgelands, the Obridge viaduct carries heavy traffic high over the Tone

2

TAUNTON

River Tone

Fifteen miles from its steeply wooded headwaters on the slates and shales above Clatworthy reservoir, the Tone in Taunton is probably as pure a post-industrial fly-fishing experience as you’ll find in south-west England. The river’s big-skied, big-scaled urban middle-reaches feel a world away from the deep coombs of Exmoor and the Brendon Hills. But even under the Obridge viaduct, with construction lorries shuttling overhead to the aggregates plant, and intercity trains hissing along the opposite bank, the wild trout and grayling are here.

Taunton grew up as a hub of the wool trade. Three watermills appear in Domesday Book, the Bishop of Winchester owned a fulling mill from 1224, and its markets extended as far as Africa by the end of the fifteenth century. Silk-weaving reached the town in 1788, followed by machined lace, shirt-collar making, brewing and iron foundries. Upstream, Wellington’s Tonedale Mills became the largest integrated wool-milling complex in the West Country, employing 4,500 workers and assuming national importance by developing the first khaki dye for military uniforms during the Boer War. (Production at Tonedale ceased in the late 1990s, but not before dieldrin mothproofing fluid, used as an alternative to DDT, reportedly killed invertebrates, fish, and a pair of otters as it biomagnified up the food chain after a spill in 1972).

As well as pollution, the Tone has suffered from significant re-engineering. At the top of the town water, French Weir dates from 1587 at least, and marks the traditional head of navigation between Taunton and the tidal River Parrett at Burrowbridge. Until the Bridgwater and Taunton canal opened in 1827 to offer a more direct transport link, milling and navigation interests continually collided on the mainstem of the river – with mills, lock gates and regular dredging at Firepool, Obridge, and Bathpool all designed to solve the bargees’ nightmare-combination of steady gradient and shifting sandy substrate.

But the Tone’s real problems probably began in October 1960. After ten inches of rain over the Somerset Levels, the river burst its banks, and several hundred Taunton homes and businesses disappeared under 3ft of water. Estimated costs of £1.7 million ruled out a flood relief channel based on the canal, and made way for a cheaper but far more environmentally damaging option: an aggressive programme of river straightening known as the Tone Valley Scheme. Between 1965 and 1967, old pictures show how the narrow, meandering channel below Taunton was dredged into a featureless drain, including a mile-long straight shot from Obridge to the Bathpool meander already cut off by Isambard Kingdom Brunel for his Bristol to Exeter railway in 1824.

Even a shopping trolley can create a vital pocket of slower-water habitat in highly-modified rivers like the Tone at Firepool Weir

And so the river remained – until the Environment Agency was created in 1991 to bring a newly integrated approach to statutory flood defence, environmental protection, conservation and fisheries. The earlier National Rivers Authority had already persuaded late-1980s housing developers to pay for extra flood water storage in new wetlands at Hankridge Water Park. Now, in 2006, the EA saw no harm in trying to improve the health of the Tone by installing low sandstone boulder weirs and chutes at strategic points along the sterile Obridge to Bathpool straight, creating slightly deeper pools upstream of the weirs, and pools and riffles below – a diversity of habitat niches for different insects, fish and plants.

Today, ranunculus has taken hold in ‘the fast stretch’ (as locals call it), the river is quietly dropping its own willow sweepers into the not-quite-straightened half mile above the viaduct, and fly life is slowly recovering to levels that even George Dewar might have recognised when he wrote The South Country Trout Streams in 1899: ‘May-fly, March brown, February red, blue uprights and duns’. Members of Taunton Fly Fishing Club have been kick-sampling the Tone and Yarty since 2006 as part of the Riverfly Partnership’s Anglers’ Monitoring Initiative, and although the river is still suffering from siltation problems due to run-off from shallow-rooted maize crops sown on sandy soil, co-ordinator John Woods confirms that invertebrate counts seem to be improving in the Bathpool area, thanks to recent upgrades at Taunton’s sewage treatment works.

Certainly my own cursory rockturning reveals baetis and blue-winged olive nymphs as well as pollution-sensitive rhyacophila caddis. It’s a match-the-hatch situation which is vindicated when a grayling grabs my tungsten beadhead nymph in the scour below one of the boulder chutes: real evidence of water and localised habitat quality, though I might not have risked a multi-fly rig so freely if I’d seen the crusted layers of shopping trolleys in the depths of the pool before casting.

Messing about in boats: locals still paddle on the historic Tone Navigation

The ponding effect from Firepool Weir reaches far upstream into central Taunton.

In low flows year round, Wessex Water guarantees minimum compensation of 4.54 megalitres per day from Clatworthy reservoir, and fish of all species stack up in the oxygenated water below the river’s weirs. Walking up through the town centre past the Somerset county cricket ground, the right angle of light slicing into water 8 or 9ft deep reveals trophy-sized chub, roach, dace, carp and bream. Small numbers of salmon are also known to migrate up from the Parrett, and when the river’s not too coloured, gravel shallows at French Weir make wading and sight-fishing for all species a real possibility. “You’ll almost certainly catch trout and grayling up there,” says Kevin Gregson, chairman of Taunton Angling Association. “Some of the trout will have been stocked by the fly-fishing club, but there are wild ones as well.”

So what does the future hold for Taunton and the Tone?

When Blackthorn’s cider-making operation moved away to Shepton Mallet around the turn of the century, and the livestock market closed after eighty years at Priory Bridge Road, the town seemed directionless, marooned in a tangle of ring-roads, with dereliction at its heart. But as the bulldozers shuffle endless piles of rubble, and the lorries rumble over the viaduct, urban regeneration is coming to Taunton. Better still, it looks likely to benefit the Tone.

Beside Firepool Weir, at the junction of the river and the canal, the seventeen-acre site of the former livestock market is slowly being reborn as a ‘commercially viable net zero carbon development’. Over a period of ten years, Project Taunton plans to build 14,000 new homes, 2,500,000sq.ft of office and retail space, and create 11,000 new jobs.

Developers have been briefed to incorporate sustainable urban drainage systems including grass swales, storm-water run-off attenuation ponds and reedbeds, and the buildings are required to have green or brown roofs as well as roosting and nesting areas for birds.

The Tone has been recognised as a major wildlife corridor from Exmoor all the way to the Somerset Levels, with bio-engineering recommended to restore diversity along its banks, low-intensity lighting for the benefit of bats and otters, and ‘significant blocks of undisturbed natural habitat’. After many hundreds of years, big business may finally be about to bring Taunton’s river the improvements it deserves.

A healthy grayling from the Obridge stretch indicates great water quality …but beware of shopping trolleys!

Taunton: River Tone

Who’s looking after the river?

Taunton Fly Fishing Club has been monitoring the Tone’s invertebrates since 1996, and the benefits of habitat work on the club’s beats upstream (such as installing large woody debris and influencing landowners to fence livestock out of the river) will eventually be felt on a catchment scale.

The upper Tone has been identified by the Environment Agency as a key catchment for river restoration to meet the standards of the Water Framework Directive, and the EA will also be closely involved in biodiversity enhancements linked to Project Taunton.

For the latest information,visit:www.tauntonflyfishing.co.uk www.environment-agency.gov.uk

Getting there

The Tone Navigation is 5 minutes’ walk from Taunton station: from here, it’s about 10 minutes upstream to French Weir. The Obridge and Bathpool stretches require longer walks downstream.

Maps of Taunton are available from the Tourist Information Centre on Paul Street, TA1 3XZ: OS Explorer 128 is also recommended.

Seasons and permits

On the town water, brown trout season runs from 1 April to 15 October. Below Firepool Weir, Taunton Angling Association permits fishing for all species during the coarse fishing season only: 16 June to 14 March.

Taunton Council allows free fishing with a valid EA rod licence through the centre of town from Firepool Weir to French Weir. Taunton Angling Association controls 6 miles of water from Firepool Weir downstream through Obridge and Bathpool to Newbridge.

For a full list of day and season ticket outlets, visit www.taunton-angling.co.uk

Fishing tips

The Tone is classified as a cyprinid fishery below Bishops Hull, so a full mix of species can be expected: chub to 6lbs, brown trout and perch to 2lbs, grayling to 1½ lb, plus roach, rudd, carp, bream and tench. Salmon to around 5lbs have very occasionally been caught at French Weir.

A rod of 9 to 10 ft, rated for a 3 to 5 weight line, will help you to land the larger residents. The Tone’s grayling tend to shoal with chub, and local lore suggests drifting small weighted Hare’s Ear or Pheasant Tail nymphs between the weed beds, or matching the hatch when fish start rising.

Don’t miss

• Clatworthy reservoir: hidden in the Brendon Hills, with fishing available via Wessex Water

• Massed winter flocks of starlings in the big skies at Obridge

• Creative local graffiti on many walls and bridge piers

Tavistock’s Abbey Weir provides a staging-point for sea-trout and salmon smolts on their way down to the Hamoaze estuary

3

TAVISTOCK

River Tavy

If stark granite tors and high moorland blanket bogs are the modern visual and ecological riches of North Dartmoor’s Special Site of Scientific Interest, the deeper veins of copper, lead and tin under Britain’s largest area of granite have provided the region with more immediately bankable wealth for more than 4,000 years.

From the start of the Bronze Age, when early metallurgists discovered that adding a small proportion of tin to molten copper created a harder and more useful alloy, tin became a key commodity of the international economy. Phoenician sailors extended their trade routes west of the Mediterranean to discover new supplies, and almost certainly reached the shores of Cornwall and Devon where the first local tinning operations were working surface veins and alluvial deposits in the gravels of fast-flowing upland rivers like the Taw, Dart, Okement and Tavy.

By all accounts the valley of the Tavy has always felt isolated by the wide expanses of Dartmoor, and the 22-mile river still runs clear, rocky and slightly acidic down its western flank to meet the Tamar estuary in the drowned river valley of the Hamoaze, a natural harbour off Plymouth Sound. Tavistock is situated at a point where the river once widened and shallowed, and the surrounding area is scattered with archaeological remains from the Bronze and Iron Ages. As early as 1305, residents shared the distinction of stannary duties – weighing, stamping and assessing mined metal for taxation – with Ashburton, Chagford and Plympton, and more than eighty mines are recorded in the immediate area. But wealth also came from the woollen trade. By 1500 there were at least 15 fulling or tucking mills within a two-mile radius of the town, damming leats and tributaries of the main river to power hammers that beat raw woven wool into felt and produced rough cloth known as ‘tavistocks’ and ‘kerseys’.

When the West Country’s woollen industry went into its late eighteenth century recession, tin mining saved Tavistock from becoming a backwater of the early Industrial Revolution, and the town was transformed after Devon Great Consols copper mine opened in 1844 near Blanchdown.

Four large foundries wrought and cast the ironwork for the mines and built metal-plated barges for the Tavistock Canal, dug by French prisoners of war. These barges transported copper ore down to the navigable River Tamar at Morwellham Quay. The town’s population soared, and the profits from producing half the world’s copper paid for almost total urban reconstruction according to plans drawn up by the seventh Duke of Bedford, whose crest can still be seen on many buildings.

Tied by Tim James: a local selection of quill-bodied dry flies for the Tavy

With the Tavy’s water already being exploited for power and cooling, it wasn’t difficult to imagine total re-engineering, so the Duke obtained an Act of Parliament to move the river fifty yards sideways to make room for the now-famous Pannier Market. Spilling under an ancient packhorse bridge, the resulting pool is probably the best dry fly water in town: a beautiful long glide with the stone solidity of former foundries and warehouses at its head, and the Abbey Weir below. In early summer, you can watch salmon smolts moving down the river in great silver shoals, circling between the fish pass and the Abbey Bridge, sometimes skittering across the surface in excitement as they feel the pull of the sea and the next big spate.

In the past, both these smolts and the river’s resident trout risked getting drawn down the intake to the Tavy canal and the Morwellham hydro-electric power plant, but an automated Environment Agency screen now keeps the river’s migratory fish populations out of trouble.

On either side of the mid-town re-engineering, the Tavy rapidly rediscovers its natural deep-pool and riffle character, with general water quality immeasurably improved since the boom years of the mines and foundries in the 1860s.

Tiny but jewel-like, a Tavistock trout comes briefly to hand

Today the catchment is mainly rural and free from intensive agriculture, and there are few pollution problems from either farming or industry. “Occasionally someone puts something down their drains in Tavistock, but we keep an eye on that and jump on it pretty quickly,” says recently-retired EA bailiff Dave French, who stood down from duty in 2010 after 35 years in post. As a result, fly life is prolific, with plentiful baetis, stonefly nymphs up to an inch and a half long, and caseless caddis that can often be seen pulling themselves back upstream on silk threads.

Looking downstream from Tavistock’s packhorse bridge: a perfect place to spot early-season trout rising to large dark olives

Many of the Tavy’s sea trout smolts return as seven-pounders among salmon twice that size, and even the resident browns run large for a West Country river. Environmental consultant Dave Brown puts this down to a combination of water chemistry and pool structure: on its course down from Dartmoor, the Tavy benefits from a varied, slightly richer-than-average Lower Carboniferous geology including deposits of sandstone and limestone, and its steep gradient cuts deep, impregnable gorge pools with plenty of cover for trout to get big, avoid predation, and finally turn predatory themselves.

Local guide Tim James confirms this theory of large trout moving around the river. “In mid-November, most of the larger fish migrate up the weir in the town centre to the upper reaches on the moor, where you can see them spawning amongst the salmon – they move back down into the middle river by mid-May. But they’re cyclical too, so when there are too many pound-plus fish in the river, most will migrate to sea, and there may be fewer large fish in the town water the next year.”

As the UK’s first ever amputee instructor, Tim is a fishing guide with a difference. Invalided out of the army after an accident, he spent years wearing a leg brace, enduring years of morphine and repeated surgery. Finally he made the doctors’ decision for them, opted for amputation, and picked up a camo-pattern prosthetic leg left over from a Royal Marine’s own rehabilitation. He’s now involved in Help for Heroes, coaching amputee commandos from Plymouth, running summer casting courses, and planning to be fully mobile again for the 2012 season.

Along the Meadows in central Tavistock, rocky banks and shillets offer easy access to the river

Fishing the Tavistock town water in early May, the big wild trout haven’t yet made it back from the moor, but the smaller ones are a perfect match for Tim’s description: “very pretty, very spooky, and always lying where you’d least expect them in the shallow reaches, tucked into the eddy of a boulder ready to dash out and intercept food.”

As far as fly patterns are concerned, local experts’ views on flies balance nicely: Dave draws on a lifetime of experience to recommend time-tested West Country patterns including Blue Uprights, Gold Ribbed Hare’s Ears for coloured water, and Alexandras or Wake Flies for sea trout. Meanwhile, Tim reinterprets more modern classics like Peacock Nymphs and Beacon Beiges with barbless hooks, dyed-quill bodies and paraloop hackles.

“When you’re tying the paraloop, wind the hackle around a foam post so that it sits at the right height in the surface film but doesn’t sink,” he suggests, “with a tiny head over the eye for extra buoyancy in rough water. The Tavy often runs very clear, so stalking fish under cover of a broken surface will often give you a far better chance of success.”

Tavistock: River Tavy

Who’s looking after the river?

The Environment Agency took over the roles and responsibilities of the National Rivers Authority in 1996, regulating pollution, reducing flood risk and improving the environment where possible.

As the angling regulator in England and Wales, it sells over a million rod licences a year, and uses the proceeds to maintain and improve the quality of fisheries like the Tavy by tightening pollution controls and restoring habitats.

For the latest information, visit:www.environment-agency.gov.uk

Getting there

Tavistock station closed in 1968 as a result of the Beeching Report, so the nearest station is now 5 miles away at Gunnislake. The river is easily accessible from large car parks in the town, some within the old Abbey walls.

Maps of Tavistock are available from the Tourist Information Centre on Bedford Square, PL19 0AE: OS Explorer 108 is also recommended.

Seasons and permits

Brown trout season runs from 15 March to 30 September; sea trout from 3 March to 30 September; salmon from 1 March to 14 October.

Tavistock Council used to sell very inexpensive tickets, but now don’t bother due to administrative costs, so fishing is effectively free with a valid EA rod licence. The lower limit of the fishery is the A386 Plymouth Road Bridge, with fishing all the way up to the ancient packhorse bridge at Vigo Street: up to three quarters of a mile.

Fishing tips

Wild trout in the Tavy average around half a pound, but you may encounter larger residents up to 2 or 3lbs, and sea trout up to 7lbs.

A rod of 8 to 9 feet is ideal, rated for a 3 to 5 weight line. For resident trout, flies recommended by Dave French and Tim James range from traditional Devon patterns like Blue Uprights to more general Greenwell’s Glories, March Browns and dyed-quill Beacon Beiges. Gold Ribbed Hare’s Ears work well in slightly coloured water when the gold can show through. Start with very small imitative nymphs in early season, with pheasant tail and peacock herl for texture and bugginess.

Don’t miss

• Tavistock Pannier Market, for which the river was moved in the 1850s

• Devon cream teas: reputedly served by local monks as refreshments for workers restoring Tavistock’s Benedictine Abbey, sacked by Vikings in 997 AD

Fish on! The author hooks a wild trout in Tiverton’s Amory Park

4

TIVERTON

Rivers Exe and Lowman