Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: New Island

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

A pair of novellas, set over two pivotal summers in the lives of two young men from Belfast, recall the constraints of the place where they were born and the times in which they are living. Summer on the Road It's 1980 and in the last summer before his A levels Mark lands a job he didn't even know he had applied for, sweeping streets for Belfast City Council. Called 'binman' by his schoolfriends, 'snooty' by his workmates, he can't imagine anything less like a holiday. Day by day, though, navigating bomb scares, punishing hangovers, broken television sets and a loving but chaotic home life, he begins to glimpse a path all his own, even if he can't see yet where exactly it is going to lead. Last Summer of the Shangri-Las Three years earlier Gem has driven his mother to the brink. She packs him off to stay with his aunt in New York during the infernal heat of the summer of 1977. It's the summer too of disco, of punk, the summer of Sam, and Elvis dead on the bathroom floor. For Gem though it will forever after be the summer he met Vivien – as rooted in the city as he is adrift; the summer he stumbled on Mary, Liz and Margie, three-quarters of the greatest New York group of all (and they'd fight anyone who said otherwise); the summer he learned how to go home. Capturing the innocence of adolescent boys, their passion, confusion and yearning, Two Summers is for anyone who has ever been young.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 262

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Also by Glenn Patterson

FICTION

Burning Your Own

Fat Lad

Black Night at Big Thunder Mountain

The International

Number 5

That Which Was

The Third Party

The Mill for Grinding Old People Young

The Rest Just Follows

Gull

Where Are We Now?

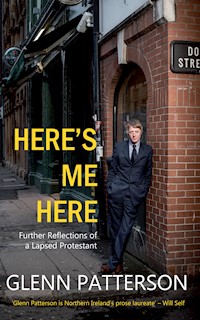

NON-FICTION

Lapsed Protestant

Once Upon a Hill: Love in Troubled Times

Here’s Me Here

Backstop Land

The Last Irish Question: Will Six into Twenty-six Ever Go?

TWO SUMMERS

First published in 2023 by

New Island Books

Glenshesk House

10 Richview Office Park

Clonskeagh

Dublin D14 V8C4

Republic of Ireland

www.newisland.ie

Copyright © Glenn Patterson, 2023

The right of Glenn Patterson to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright and Related Rights Act, 2000.

Print ISBN: 978-1-84840-898-2

eBook ISBN: 978-1-84840-899-9

All rights reserved. The material in this publication is protected by copyright law. Except as may be permitted by law, no part of the material may be reproduced (including by storage in a retrieval system) or transmitted in any form or by any means; adapted; rented or lent without the written permission of the copyright owners.

This book is a work of fiction. Names, characters, businesses, organisations, places and events are either the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or locales is entirely coincidental.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data. A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Typeset by JVR Creative India

Cover design by Niall McCormack, hitone.ie

New Island receives financial assistance from the Arts Council/an Chomhairle Ealaíon and the Arts Council of Northern Ireland.

New Island Books is a member of Publishing Ireland.

Set in Adobe Caslon Pro in 12 pt on 17 pt

For the sweepers and the singers

Contents

Summer on the Road

Last Summer of the Shangri-Las

Summer on the Road

THAT WAS THE SUMMER Mark was sleeping on the sun lounger in the front room. Jilly had come home from Edinburgh the week after Easter with Danielle. Second time since the New Year.

‘I’m not going back this time,’ she said. She said that the last time too. Then she had stayed less than a week, most of it out in the hall on the phone, Danielle on the floor at her feet playing with whatever the telephone seat drawer yielded up by way of toys: neighbours’ spare keys, Goodwill Offering envelopes for Sunday services long since passed, squirmy elastic bands that Jilly said were a choking hazard and shouldn’t be there.

‘They shouldn’t be there?’ her father said. ‘They shouldn’t be there?’

He didn’t finish. He rarely did.

Jilly went back to Edinburgh and three months later came home again. Ten weeks now and counting.

She had had the box room when they were growing up, being the eldest, being the girl. Her room had been off limits to Mark and Dennis, the only door in the house other than the bathroom door, facing it down the landing, that was ever shut.

Which only seemed to make her more paranoid.

‘Which one of yous was in my room?’ she would say at dinner.

‘It wasn’t me.’ (Mark)

‘It wasn’t me.’ (Dennis)

‘It was me.’ (Mother) ‘I had to put away your ironing.’

‘I could have put it away myself.’

‘The last lot was still sitting on top of the chest of drawers.’

‘I’ve been busy, in case you hadn’t noticed.’

Mark didn’t know about Dennis, but he did go in there sometimes, those very rare occasions when there was nobody else in the house, on the lookout for magazines – between the mattress and the bed base, the more grown-up ones were – hands sweating as he searched them for the problem pages.

My boyfriend says if I loved him I’d go all the way.

I am embarrassed by my hair you know where.

I am seventeen and still haven’t had my first period.

Are you really supposed to blow?

Jilly clearly couldn’t go back into the box room, not with Danielle, and the travel cot (it weighed a ton when he carried it up the stairs for her) and all the other bits and pieces it took to keep a baby of fourteen months going from one day to the next.

The original plan was Mark and Dennis would alternate on the sun lounger, till Dennis said, ‘Well wait a minute: I’ve my O levels coming up. Nobody made Mark sleep on a sun lounger last year.’

‘Sure, why would they have? Jilly wasn’t here last year.’

‘It doesn’t matter: nobody made you.’

‘He has a point,’ their father said and nodded.

‘Oh, listen, if I’m making everybody’s life difficult,’ Jilly said.

‘You’re not,’ said their mother. ‘Mark can sleep on the lounger on school nights and Dennis can sleep on it at the weekends. There.’

‘I have to revise at the weekends too you know,’ Dennis said. He had his head down, but Mark knew he was smiling: he had hardly had a book in his hand all year.

‘You can swap as soon as the exams finish,’ said King Solomon, in their father’s voice but then midway through June a friend of his whose wife worked in the City Hall told him of openings in the Council’s cleansing department – holiday cover for roadsweepers and binmen – and without even talking to Mark about it he said sure, why not, put his name down.

‘I thought it’d be money towards when he goes to university,’ he told Mark’s mother, the day the letter dropped on the mat with word – the first anyone else in the family had heard about it – that Mark had been offered the job, starting first Monday of July. ‘And he’ll get a donkey jacket out of it.’ Which, since it sounded as though he wasn’t going to get to hold on to much of the money, was actually the one detail of the deal Mark could see in his favour.

‘Now, the only thing is, the depot they have assigned you is over the far side of the Shankill Road.’

‘The Shankill! What time does he have to start?’

‘Half seven.’

‘He’ll have to be leaving here about quarter past six if he’s to be there on time. It’s two buses.’

‘Does that mean I’m going to be woken up every morning with him clomping through the living room?’ Dennis said. ‘Some rest that’s going to be for me!’

‘He has a point,’ said their father.

So Mark was sleeping in a sleeping bag on the sun lounger. Or not sleeping a whole lot. There were the springs for one thing. Twelve of them in all. Thick and hard and, after even a minute or two away from direct sunlight, cold. They really only left you a strip up the middle about two feet wide to lie on.

And then there was Danielle.

Some babies woke smiling no matter what hour of the day or night, his mother said, and some babies never woke but they howled. ‘I had two smiley babies and one howler – you – in between, which just goes to show you.’

Don’t be too hard on the wee thing, in other words, even if she’s doing her howling right above your head at five o’clock when you have to be up in an hour for your first day at work.

He was up and dressed, in the end, twenty minutes before his alarm was due to go off. He had washed the night before so that he wouldn’t have to go up the stairs, though how any of the rest of them slept through Danielle’s waking and being changed and put back down again for another hour or two – ‘please, for Mummy’ – was beyond him.

His mother had left him out two pieces of bread buttered side up on a sheet of tinfoil and a bowl beside them with sliced tomato in it. Next to the bowl she had left a piece of paper with the address of his Great-Aunt Irene (‘round corner from old place’, she had added in brackets), though as his father had already said she was on the other side of the Shankill entirely, and it wasn’t as if Mark was going to have time in his day to just dander across there and say hello.

He made up the sandwich and put it in the pocket of his bomber jacket and let himself out by the back door.

He passed a wee lad out on his bike delivering the early morning papers, but apart from him, and the far-off whine of the milk float, stopping and starting, stopping and starting, no one appeared to be out and about. Not even the fellas who boasted about sitting out all night to guard the Eleventh Night bonfire, on the waste ground at the entrance to the estate.

The estate was on a Blue Bus route, which meant it was technically outside the city limits. The first bus didn’t leave until seven o’clock. The stop for the Red Bus – the City Bus – was another fifteen minutes’ walk through the estate next to his. Half a dozen people were waiting, all in their own wee worlds, though they turned as one when he joined them on the footpath, almost as though he had gatecrashed a party. The bus, coming from a third estate, was a single-decker, a quarter full, mostly down at the back in the smoking seats. Mark stood near the front in the space for baby buggies, hanging on to the strap and watching the suburbs gather themselves into the city proper. Still the only shops open were newsagents and petrol stations, but at every stop more people got on, so that by the time the bus pulled up at the side of the City Hall, Mark was pressed right up against the window.

He had to pass inside the security gates on to Donegall Place to catch his second bus. It was nearly always civilian searchers these days, with just a couple of soldiers standing behind chatting to each other. A couple of Rag Days back, four men in fancy dress had stepped out from the students throwing flour at passers-by and shot a soldier and a woman searcher at the gate near the cathedral.

Mark saw himself in the angled mirror above the way out raise his arms while a searcher waved a wand vaguely about his legs and up his back. A second guy patted him down. Came back to his jacket pocket for a second pat. (His bomber jacket, for fuck sake.) A squeeze.

‘What’s that in there?’ he asked.

‘My lunch,’ Mark said and went to take it out, but the guy shook his head: on you go.

Two Rag Days ago: aeons.

A church bell (where was it?) was chiming for seven o’clock as the second bus – another single-decker – pulled in. Again Mark stayed near the front, further forward in fact and not for the view this time. He was less certain of his fellow passengers, where they were coming from and where they were getting off. The route passed through Carlisle Circus – Shankill on the left side, New Lodge on the right: Protestant, Catholic, you might as well say – and then up the Crumlin Road, between the courthouse and the jail, as far as Agnes Street on the Shankill side, which was where Mark had been told he should get off. After that he didn’t know: Oldpark, maybe, or Ardoyne, both places he had grown up understanding he ought to avoid.

Of course nobody said a word of any sort to him.

As he was standing waiting to cross the road though, a wee girl sitting on the back seat next to her mother gave him the fingers up the side of her nose.

Then the bus pulled away and he was looking up the long street of three-storey houses that led to the Council depot.

He zipped up his bomber jacket and jogged across.

First thing he noticed when he reached the end of the terrace were the bullet holes in the pillars supporting the corrugated iron gates. You could nearly have drawn a straight line joining the holes on the left and the holes on the right. He remembered as a kid making a machine gun out of fists held one in front of the other, sweeping them from side to side: dow-dow-dow-dow-da-dow-dow-dow-da.

‘M60.’ A fella in Council overalls was coming up behind him. Must have seen Mark looking. (He hadn’t actually made those fists, had he?) What little hair the fellow had was golden in the early morning. A barley field after harvest. ‘Year before last. Provos took over a house just across the peace line there.’

The ‘peace line there’ consisted of more corrugated iron with, on this side of it, hymns to the UVF and FUCK THE IRA.

‘Bastards.’ Another, ganglier skinhead fell in beside. ‘You one of the summer boys?’ he asked Mark. ‘What school are you at?’

‘Methody.’

‘Hear that, Tony? Fucking Methody.’ He brushed the tip of his nose a couple of times with his index finger: snooty, snooty. ‘Did you need an atlas to get here? A chauffeur?’ He spat through his teeth. ‘Fruit.’

‘I have an aunt lives down the road,’ Mark said. Greataunt sounded too remote. Like other side of the Shankill entirely.

‘Oh, yeah? What’s her name?’

‘Irene. Irene Bell.’

‘Never heard of her. You heard of her, Tony?’

Tony shrugged. ‘I know a whole load of Bells.’

The other skinhead cackled. ‘Load of balls, you mean.’ And he arched his back in anticipation of a toe up the arse that was never in the end aimed.

The depot – the yard – was about the size of the main quad at school, only instead of the assembly hall there was a garage for the bin lorries, instead of the sixth-form centre there was an open-fronted shed with street-sweeping carts in various shapes and sizes. The office was on the left, about where the staffroom would be.

‘You’ll need to see the foreman,’ Tony told Mark.

‘Samson!’ The other skinhead rubbed his hands together. ‘He’ll put some manners on you, the same boy.’

‘Fuck sake, Alec, leave the wee lad alone,’ said Tony and the two of them went into the building by another door.

The corridor Mark found himself in smelled of bleach. More than bleach. It smelled of the place where all the other bleach in the world was made.

Two other boys were sitting at the end of it, three orange seats apart. Mark recognised the one farthest from him from the year above him at school. Funny name. Casper? One of the dope-smokers anyway. Early 70s throwbacks who had set their stoned faces against all recent musical trends. The world began and ended for them with Genesis. And lo it came to Trespass that with a Trick of the Tail the Lamb did on Broadway Lie Down. His features were squeezed into a three-inch strand of face between the tides of his centre-parted hair, which needed constant tugging and flicking to keep it from encroaching further. He tilted his chin a fraction in recognition.

‘Is this where the foreman is?’ Mark asked as he sat in the seat midway between him and the other boy.

‘Supposed to be,’ said Casper.

The other boy consulted his watch, black eyebrows knitting. ‘It’s only twenty-eight minutes past.’ His voice hadn’t so much broken as plummeted to the bottom of the well. He had the look of a rugby player – not schools rugby, one of those scrappers you saw on Grandstand on Saturday afternoons. Widnes v Warrington from Naughton Park. ‘They told us half past.’

Two minutes later (‘to the second’ the big lad said out the corner of his mouth and from the very, very depths), the door opened and a man came in. He was not much over five foot tall, a stone at best for every foot, bald but for a couple of tufts above his ears. They appeared to have been dyed plum, the tufts on the left a shade lighter than the tufts on the right. He couldn’t have been anyone but Samson.

‘Grammar school boys are yous?’ he asked. ‘You know yous are taking men’s jobs?’ Mark, Casper and the big lad looked at one another. Holiday cover, that’s what it had been described to them as. ‘So who pulled the strings for you?’

The big lad put up his hand. ‘I’ve been doing this the last two summers,’ he said.

‘Oh, aye, and where were you before?’

‘Clara Street and Park Road.’

The foreman humphed, ‘Nowhere you had to do any real work then.’

‘When do we get our boots?’ Casper asked. They all looked down at the sand-coloured desert boots sticking out from the ends of his cord flares.

‘You want boots?’ the foreman took a step towards him so that they were nearly eye (standing) to (seated) eye. ‘You’ll get them when you’ve been here six weeks. Same goes for your donkey jacket and overalls. There were men walking out of here at the end of their first day all kitted out and then never coming back again. This yard must have dressed half the bucking Shankill. You’ll see them yet – picked the letters off the back of jackets, of course, but I’ve got eyes, I see the outline: BCC. You know what that’s for?’

Mark assumed he didn’t intend the obvious answer.

‘Before Charlie boy here Cottoned on.’

‘BCBHCO,’ Casper said under his breath.

Samson though had turned his attention to the big lad. He looked him up and down. Fruit of the Loom T-shirt, Wrangler jacket folded across his lap. ‘Two summers you did? Where’s all your gear, then?’

‘I grew out of it,’ he said, and the muscles under his T-shirt flexed.

‘I might have bucking known.’ Samson shook his head. He went into his office and came out with three pairs of gloves, gauntlets more like, deep cuffs and some sort of padding or reinforcement at the fingertips and knuckles. ‘That’s all yous are getting for now, and look after them. Any lost gloves you pay for yourselves. Understood?’ They all three nodded. ‘Come on, well, if you’re coming.’

He brought them through to the room where the rest of the men were gathered. About twenty in all, late teens through to mid-sixties. Tony had taken out the Sun and folded it open at the sports pages. His skinhead friend – Alec – was trying to sneak a look at Page Three.

‘Who’s it the day? The Lovely Linda? Wee Dee?’

‘How would I know?’

‘Don’t pretend that’s not why you get it.’

‘Right!’ Samson shouted and jerked a thumb over his shoulder. ‘These are your new playmates. Give them whatever help they need.’

‘Us help them?’ a man with no front teeth said. ‘I thought they were supposed to be helping us.’

‘I’m sorry to disappoint yous,’ said Samson. ‘Take it up with your MP, why don’t you.’

Mark was put on a squad with Alec, who rolled his eyes and sighed, and an older man who got Benny after your man out of Crossroads because of his woolly hat. They crossed the yard with the other squads and stopped in the shed before a cart with worn wooden handles and a shovel lying lengthways between two metal brackets on the near side. A pair of brushes balanced on the top. The heads were a good eighteen inches wide. The bristles looked battle-hardened. Alec and Benny grabbed a brush each and walked off with them over their shoulders. Halfway to the gates Alec looked back to where Mark was still standing beside the cart.

‘What do you want, an invitation? Come on to fuck!’

Mark took a hold of the handles and raised the cart’s rear end off the ground – too high. The thing tipped forward on its two front wheels then, when he tried to get it back under control, veered off to the left and into another cart sending its brushes and shovel clattering to the floor.

Samson was showing the big lad – whose name it had now been decided was Big Lad – how the larger electric carts worked, pulling down on the lever sticking out from the front to start the motor. He turned to Mark. ‘If you’re not up to this, you know, I can walk out on to the road there and get someone who is, quick as that. There’s hunderds would be glad of the chance.’ He was practically levitating. ‘Hunderds!’

Over by the gates Alec and Benny were doubled up laughing.

Mark picked up the fallen tools, steadied the cart and pushed it across the yard and out the gates. The road down to the Crumlin Road – enough of a stretch when he had to walk it from the bus stop half an hour before – seemed twice as long. Alec and Benny had already crossed on to the Shankill side by the time he got to the end of it. Only for Benny’s hat he wasn’t sure he would have picked them up, turning into a street on the left.

They dropped their brush heads to the road, Alec on one side, Benny on the other, and set about the bits and pieces of rubbish along the gutters, stopping every ten or twelve feet when they had made a pile, a little swivel of the brush to neaten it up.

Mark set the cart down, unhitched the shovel and pushed it under the first pile without being bid. The dirt, the rubbish, went everywhere.

He stared in disbelief.

‘Man, dear. You’re meant to come at it from the side,’ Benny said. ‘Shovel in against the kerb.’

Mark was chasing after a Quencher wrapper he’d sent flying with his first attempt, trying to trap it with his foot.

‘Never mind that,’ said Alec. ‘We’ll get it tomorrow.’

Even coming at the piles from the side like Benny said, Mark lost about half of every shovelful between kerb and cart. Another street opened up on the right. Alec and Benny turned into it. Mark eventually followed behind. The piles were already waiting, but of Alec and Benny there was no sign. He started shovelling, all the time wondering where they had got to. Just short of the next junction he heard a whistle. Sounded like it came from the entry running at right angles to the street he had been working on. He looked in. No Alec or Benny. Then another whistle. A few yards in another entry opened, completely obscured from the street. He pushed the cart ahead of him round the corner.

Alec and Benny were standing leaning against the wall. They threw their brushes across the top of the cart as soon as Mark set it down then walked back down the alley, hands in their pockets.

‘What are we doing now?’ Mark called after them.

‘Tea break,’ Alec said. ‘See you back here at eleven.’ It was barely quarter past eight. He stopped at the corner. ‘And for fuck sake make sure you keep out of sight.’

For two and three-quarter hours?

It crossed his mind to go and see his Great-Aunt Irene, but he had only the vaguest idea of where he was and next to no idea how to get from there to her street. While keeping out of sight. The only thing he could think to do in the end was to sit down against the wall next to the cart. At least the ground was dry. Warm too, surprisingly. He had been on the go from well before six. He was going to be on the go before six every weekday morning from now until he went back to school in September.

Six-a-fucking clock. Six-a-fucking clock.

Next thing he knew someone was kicking his foot. He leapt. Alec. He and Benny had their brushes over their shoulders. ‘What do you think this is, fucking Butlin’s?’

They headed back out on to the street they had already swept and turned off into the street cutting across it. The same kitchen houses, one window downstairs, two windows up, front doors opening directly on to the footpath. The same red tiled steps. They did that one and maybe five others, Alec and Benny brushing, Mark – with more success every street they went down – shovelling, before Benny and Alec threw their brushes across the top of the cart again.

‘That’s lunch,’ Alec said.

‘Do you want me to put the cart in one of the entries?’

‘Why would you do that? Take it back to the yard. See you at half one on the dot.’

It must have taken him twenty minutes getting back. With all his struggles, it hadn’t seemed at the time as though there was much going into the cart, but now – the weight of it – it was harder than ever to keep it balanced. As he passed between the broken line of bullet holes his arms felt as though they were being dragged right out of their sockets. The yard was deserted. Except for Samson.

‘Empty your cart!’ he yelled from the office doorway the second it came to rest. Mark walked around it with the shovel, wondering how the hell he was going to manage this. You’d have to stand on the bloody thing to get the right sort of leverage.

It didn’t help that he had Samson watching him the whole time. Ah, fuck it. He had the shovel raised, the top of the handle a good foot and a half above his head when Samson came walking across the yard and with his little finger lifted a tiny hook at the front of the cart. A door swung open.

‘You tip the bucking stuff out,’ he said and walked away.

So that’s what Mark bucking did and only then did he reach into the pocket of his bomber jacket for his tomato sandwich … What was his mother thinking? What was he thinking? Tomato sandwich! Even before he unpeeled the tinfoil he could tell it was squashed. (The press of people on the bus into town. The double pat of the civilian searcher. All that raising and lowering of the cart.) A soggy red wedge.

He ate the drier, thicker end where he stood in the shed and threw the remainder in with the other rubbish. He only just had time for a slash before he had to pick up the cart and hightail it back to the Shankill. Alec and Benny sauntered round the corner a minute or two after he arrived. Stopped in their tracks.

‘Where are the fucking brushes?’ Alec said.

He had forgotten to put them back on the cart.

‘We can’t fucking work without brushes. Come on ahead, Benny.’ And round the corner they went again.

The afternoon passed as the morning had. Nothing he did was right, or, if it was right, done on time. At one point he thought about just chucking down the shovel and walking away. Maybe all those men Samson gave out about who never came back after the first day weren’t just motivated by the donkey jacket and boots. But where else was he going to get in now that the summer was started? And though university was still more a notion – a hazy one at that – than a definite plan, his father was right, he was going to need money whatever he did once school was ended, and he couldn’t look to his parents for it.

He kept shovelling.

Big Lad was at the yard when he and Alec and Benny got back for knocking off, a couple of minutes before half past three. He had grown a beard since the morning, full and black. ‘They sometimes make me go and shave at lunchtime in school,’ he said. ‘Apparently it unnerves the teachers.’

Casper arrived at that moment.

Alec pointed. ‘Look at fucking Brainiac.’

His desert boots were lilac. He had picked up a discarded tin of emulsion paint only to find it wasn’t as empty as it looked and had had a hole punched in the bottom.

‘There’s wee lads would put a hole in the bottom of a tin just for the laugh of it,’ one of the other men said as they tipped out carts and returned them to the shed. ‘You need to pick up the like of that with the handle of the brush.’

‘And see plastic bags?’ Alec added with relish. ‘Shovel every time, or phlttpp’ – he flicked out his fingers towards Casper’s face – ‘shite all over you.’

‘They’d do that too all right for a laugh,’ the other man said.

Mark caught the bus into town with Casper. (Trail of dimpled lilac prints all down the long road to the bus stop, all up the central aisle of the bus.) Not a word out of him until they were coming up to the security gates at the end of Royal Avenue.

‘I hate those cunts,’ he said then.

‘They’re just taking the piss out of us a bit,’ Mark said.

A civilian searcher stepped on to the bus. Gave it the usual cursory once-over before staring at the footprints. The driver jerked a thumb over his shoulder. The searcher tilted her head until she picked out Casper’s boots. She was laughing as she got off and the driver revved the engine again.

Casper shook his head. ‘I do. I fucking hate them.’

‘Well? How’d you get on?’ His mother, across the table from him, addressed the question to Danielle sitting in her highchair at the far end.

Dinner times now revolved almost entirely around what Danielle would and would not eat. People made Os of their mouths (Mark felt himself do it, try as he might not to) as food was offered to her on the end of a fork, then closed them grimly as she palmed the fork away, scattering the cargo of Smash or sossies or Alphabetti Spaghetti.

‘It was all right,’ Mark said.

His mother opened her mouth. Closed it. Not this time.

‘Where’s your donkey jacket?’ Dennis asked.

‘You don’t get them right away.’

‘What, so it’s like a promotion?’

‘It’s summer,’ his father told Danielle, who had put her head down on top of her arms folded on the highchair’s table. No want! ‘Donkey jackets are more for the bad weather.’

Mark didn’t bother to contradict him.

‘So what did you get?’ Dennis asked.

‘Ten quid more in my pocket than you did sitting here at home.’ He was rounding up.

‘Is that what you’re going to be getting, seriously? Fifty quid a week?’

Close enough. ‘More if there’s overtime.’

Dennis whistled. ‘For pushing a brush around? Fair play.’

When he stripped off later in the bathroom his feet and ankles were black. His arms too, as far as his elbows. He pushed the rubber shower attachment on to the taps and stood in the bath hosing himself down, as he did most nights (he was too tired to do the other thing he did a lot of those nights). He didn’t know how to explain it even to himself, but he felt as though he was not entirely the same person who had stood here last night.

Danielle went off at 5.35 am. He tried for a few minutes to get back to sleep, but it was no good. Besides, he had a plan. He ignored the slices of buttered bread and the banana his mother had left out for him and boiled an egg. Didn’t matter what you did to a boiled egg, it would still be edible.