Ulysses's Cat E-Book

Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Parthian Books

- Kategorie: Poesie und Drama

- Sprache: Englisch

'A wonderful collection stemming from a hugely important project keeping young Welsh writers connected to Europe despite all attempts to sever these crucial cultural ties.' – Rachel Trezise 'Anthologies such as this one are the footings of the recently-burnt bridges that we need to rebuild. They help to tear down the walls put up around us. Always important, they are now vital.' – Niall Griffiths Ulysses's Cat brings readers the work of some of the most outstanding authors of the younger generation from Croatia, Greece, Serbia, Slovenia and Wales who participated in a project of exchange residencies originally launched on the Croatian island of Mljet, where, according to legend, shipwrecked Ulysses found shelter. As Britain becomes metaphorically unmoored and drifts away from Europe, keeping connected through reading and dialogue provides us with new perspectives on our place in the world and on the tumultuous times we live in. The works of poetry, prose and essays included here offer a snapshot of the concerns and preoccupations shared by young writers from a region with a rich literature that rarely reaches English-language readers and at the same time confirms the vitality of the bilingual Welsh literary scene.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 300

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

iiiiii

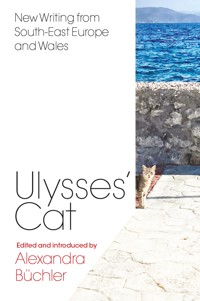

ULYSSES’ CAT

New Writing from South-East Europe and Wales

v

This anthology is published in cooperation with Literature Across Frontiers as part of the Ulysses' Shelter project of exchange residencies co-financed by the Creative Europe Programme of the European Union. Views and opinions expressed are however those of the author/s only and do not necessarily reflect those of the European Union or the European Education and Culture Executive Agency. Neither the European Union nor the granting authority can be held responsible for them.

Contents

Introduction

It all started on Ulysses’ island

Ulysses’ Cat brings readers the work of some of the most outstanding authors of the younger generation from Croatia, Greece, Serbia, Slovenia and Wales. The thirty writers and literary translators participated in Ulysses’ Shelter, a project of exchange residencies originally launched by the publisher, literary agent and organiser Ivan Sršen on the Croatian island of Mljet. There, according to legend, Homer’s shipwrecked hero found refuge (and was held captive for the best part of his ten-year journey home by the nymph Calypso). And this is how the idea of a project of exchange literary residencies was born, with the aim to provide ‘shelter’ (minus the element of captivity) for emerging writers and literary translators to spend time away from home in another country. What makes the programme particularly valuable, as opposed to the many residential opportunities for writers across Europe, is its capacity for connecting literary scenes in the participating countries and growing a network of writers who are in the initial stages of their careers.

That, in any case, was the plan when the second cycle of the programme involving five countries – Croatia, Greece, Serbia, Slovenia and Wales – started. However, the project soon faced obstacles when the Covid-19 pandemic made travel impossible, adding a new theme to contemplate and write about, that of ‘isolation’. The pandemic certainly brought into focus the importance of personal, face-to-face contact and gave us new 2perspectives on the value of physical proximity and the thrill of meeting live audiences, in short, on everything we had previously taken for granted. While the digital had already extended the repertoire of options for contact and opened up possibilities for creative collaborations and audience reach, it now became the new normal, a levelling force that cancelled distances and made geographical and cultural peripheries equal to centres. Authors who would not have met if the project had run to plan, were brought together through digital meetings and one-to-one online discussions. Others focused on their environment, given the constraints imposed by the pandemic and the forced changes to plans and circumstances, both personal and creative.

An anthology without a theme?

There is a myriad of ways to focus anthologies: geographically, generationally, thematically. The present anthology may appear not to have a theme beyond the fact that the authors included in it belong to the same project and share perhaps nothing else than a desire to step outside their cultural environments and comfort zones. And since the reference to Ulysses, apart from being a broadly literary one, is a reference to a journey, the writers have become travel companions inside a book, who meet and take turns to tell a story.

Each also represents a literary scene, making the anthology a sampler of contemporary writing by a younger generation of Europeans with multiple referential anchors, stylistic and thematic. The majority of the texts included here, however, have not emerged from the project but have been selected from recent work already published in the original language and translated into English, which is presented, in many cases for the first time, in a book intended for the English-language market that stretches well past 3the borders of countries whose official language it is. Being the indisputable European lingua franca, English is sometimes seen as threatening less-widely spoken languages, and indeed several contributions to the anthology were written directly in English. Yet, the usefulness of a common language is something made clear time and again in cross-border projects whose participants, as was the case with Ulysses’ Shelter, display an impressive command of English in addition to other languages, proving the point that a shared language, whatever it may be, does not diminish multilingualism, on the contrary, it confirms it, making communication possible across the continent and beyond with nuances that enrich rather than impoverish native languages.

Gazing east towards Europe

From the perspective of the Welsh literary scene, the anthology creates a symbolic bridge between Europe and Wales as a culturally and linguistically distinct part of the United Kingdom, a country that has, in the past six years been struggling with the decision to ‘leave Europe’ having set out on a disputed and much discussed ideological journey marked by internal culture wars. And it has been amidst the irreconcilable differences that the majority of young people and artists stand on the side of examining the roots of that decision by casting a critical glance at the country’s colonial history, external and internal, and exploring what contributes to their sense of belonging.

And so, as Britain becomes metaphorically unmoored and drifts away from Europe, keeping connected through reading and dialogue provides us with new perspectives on our own changing place in the world and on the tumultuous times we live in. The works of poetry, prose and non-fiction included here offer a snapshot of the concerns and preoccupations shared by young 4writers from a region with a rich literature that rarely reaches English-language readers and at the same time confirm the vitality of the bilingual Welsh literary scene.

Ulysses’ Cat?

And what about the cat, where does she fit in? Didn’t Ulysses have a dog, the dependable Argus, who faithfully waited for him and was the only one to recognise him when he returned? And isn’t the emblem of the project a donkey, the symbol of Mljet island where it represents the traditional means of transport, conveying enchantment with an idyllic past, simple, slow life, and solitude in the midst of nature without modern amenities?

But the literary references of the project span millennia: from the original, mythical Ulysses to his modernist namesake whose journey takes a day while its description fills several hundreds of pages. There, in the section named after Calypso, the nymph who held Ulysses in captivity, Leopold Bloom converses with his cat whose purring pronouncements – ‘Mkgnao, Mrkgnao, Gurrh!’ – become part of the meticulously detailed record of the day’s minutiae and merge with Molly’s sleepy ‘Mn’. And aren’t cats, after all, more so than donkeys, the mascots of the Mediterranean where Ulysses’ journey took place? The title then is as playfully random as it is fitting: Ulysses’ cat is a phantom, a conjecture, a proposition, an invitation to fabulize, to depart from well-trodden paths and imagine new stories, one of which could well begin on a light-bleached stone stage against an intense blue sea.

Alexandra Büchler

CROATIA

Marija Andrijašević

My sister Kamila

If I get lost I’ll send you a location pin, so you can come and rescue me, he explains as he packs for Velebit. Or send help, whatever’s easier. Don’t worry, mountains are not so cruel in spring. It is his first hike since we’ve been together, and my guts are slowly crumbling in preparation for mourning at his funeral or, worse, standing in some back row because his family doesn’t consider me relevant. They haven’t met me yet, and we’ve only been together three weeks. Love is crazy, too crazy. But also short. And short loves are uncountable. Even in contemporary times, this is love’s greatest drawback. Although our love has other drawbacks, more serious ones. It won’t be me coming, but someone from the rescue services, You’ll just have to stand quietly and wait, I think, perhaps I say it too, I definitively believe it would be just like that.

I also believe that with him I would, with time, become a rock climbing, hiking and even mountaineering enthusiast. I prepare, on the outside, carried away by his desire and yearning, note down everything I find in the pamphlets, the newsletter. My glutes will evolve from girly shapes into sporty muscles, thanks to gym machines, running schools, nordic walking, and climbing halls practice. We would always be one step behind the other, walking alongside each other, avoiding crevasses. We would stand proudly above them, literally and figuratively. Our fucking in the outdoors would not melt a glacier nor would it set off an avalanche, but it 8would mark a comma, and possibly a colon in climate change. And from the world’s peaks, drunk on passion and tired from the walking, we would sift through the clouds for lightning bolts and throw them upon the earth. I believe all kinds of things. Including the fact that our love counts, and worse – that it is love.

He cannot focus on work. He can’t stop thinking about me. Today was the first time, in the seven years he’s been working there, that he wanked off in the toilet. And not just in any toilet. In the boss’ toilet. The boss is away on a work trip. He didn’t want to take any risks. He took pictures of me at the lakes on the Savica (my trial trip to the countryside outside Zagreb) and put one of them as a screen saver on his work desktop computer. He is showing off. Domesticating me. On his breaks, and he works in the city centre as a project manager, he invites me for coffees, brunches, lunches, is late for meetings, runs across the square and shouts, under the clock where he leaves me, MARIZA, SAY YOU WILL NEVER FORGET ME. How will I forget you, you idiot, I’ll see you tonight, as you ordered, at your place, in your bed.

He has even written a short story about me. The title is ‘My sister Kamila’ after my real sister Kamila. Well, it is more of a sketch. All because he is amazed by our names: Mariza and Kamila, and the little bits of information I have occasionally shared about myself. The story is in his head, he just has to write it. He’ll do it for my birthday. He’s a writer, and his job is just to … get away from his parents, their ideas about him, it’s different from where you come from, what did you call it Prikom – or whatever.

The writer is young, good-looking, fit, with thick lips and healthy teeth, and lives in the attic of an Art Nouveau building, several 9streets away from his work. High ceilings. New windows. New paint on the walls. New wardrobes. New bed. New furniture. New floorboards. New beams. New roof. New bath. Everything feels new. New him. New me. A terrace with views of Ibler Square and the Mosque, and fountains with waves like the sea waves in Prikomurje, they awaken a melancholy in me, a feeling of familiarity. His unshaved face is lit up with the flashing lights of passing trams and seems like the most real thing I’ve ever seen. Mariza, what have you ever done to deserve such a bloke? You’ve sailed into the most beautiful bay. Careful that it doesn’t turn into a tourist attraction, you’ve seen how all of the most attractive bays ended up on the island. Our kind wants them, but we never drop anchor in them. Quiet, Kamila, shut your gob!

I am in love, I am, I tell everyone, or rather my sister and a work colleague while we shelve books and collect magazines and I move chairs and tables with my knees in our small reading room. It’s the guy that borrows four books every Monday and reads two poetry collections while browsing the shelves. You know him, I’ll point him out. Ah, I sigh from the sofa, enchanted, reminiscing about his blue eyes, long fingers, big smile, he hasn’t yet introduced me to his friends, but he will, just wait until we are really solid, I assure my colleague and myself. We’ve been together for two months now. It’ll happen any time now. And the parents.

The books are always on his bedside table, neatly placed, whenever I go around, they’re always in the same spot. Do you actually read them, I open one, the pages are stuck together, I rub the edges of the cover on my naked breasts. I do, of course, what do you know what I do when I’m alone. But when is he alone? Ever since he met me he keeps ringing me, wants me all the time, we have been, 10without a fault, glued together from the start. I’m comfortable. I have got away from the island for the first time since finishing university and spending some years back home. I have no friends or responsibilities here. But he … He cancels birthdays, concerts, barbecues, parties. I am convinced that if I don’t act in the same way eventually, he will get mortally offended. One night he cannot get an erection. He stuffs me like a turkey. It’s sickening.

It’s also sickening two days later, when he doesn’t get in touch and it’s the first time this has happened since we met. I’m worried. Maybe he’s writing. Maybe he lives like a writer. I can understand that, I console myself. He might be working on Kamila. I’m suspicious of the fact that he doesn’t ask for more details, that even if he is writing, I’ve never seen him write, he only talks about writing, and those books … Mere objects with smooth covers. Static with dust. I think about that story, as if it were mine, and it will be mine, a gift for me, but what do I do with a bad gift? I’m ashamed to be thinking of him as a bad writer. During a lonely lunch, glancing over at his office window, and thinking about the story, I sense that something is off between us. I confide in the work colleague in a roundabout way, I don’t mention being stuffed like a turkey. She tells me to google ‘silent treatment’, that her daughter was put in her place like that by a young man she’d fallen in love with when he didn’t like her openness and assertiveness, when he’d, so to speak, started feeling like he was losing his power next to her. The school counsellor said that he had learned this at home from narcissistic parents, and that this was how they regulated one another, by hurting each other. Regulating one another? We are not thermostats! But those are … problems of immaturity. Or worse, serious pathologies. And I kept quiet! A narcissist! 11

It hurts. My chest hurts the most. I cannot suck air in all the way. I fall over from the pressure at the gym, send him a message from the changing room. If I had googled what my colleague had suggested, I told myself later, who knows, perhaps I’d have sensed it in time, perhaps I’d have known not to send the message, not to apologise that evening in a bar, in public, for a simple comment about reading books, not to keep quiet when threatened with breaking up because I doubted him, that I was being too demanding and that why, oh why, can’t he find a person who for once wouldn’t question his words. I am not questioning your words, I sit silently, I am questioning what you do not do. And perhaps I’m wrong, he’s my first city boyfriend, maybe he’s right, we find it easier in Prikomurje to … handle everything that happens to us, we are toughened from a young age, by a mother who always keeps silent and a father who instead of wrinkles has scars from fishing nets and dynamite. I keep quiet, I don’t mention being stuffed like a turkey, he gives me another chance, and finally my lungs can draw in air again. I am loved!

It’s a month to my birthday. The story is still a sketch. I don’t ask about it, and he withdraws from me. Something is growing between us, and it isn’t love. My glutes are rock hard. I’m embarrassed to have such tight buttocks because they draw looks away from newspapers, trams, posters, the road. In Prikomurje old women would cross themselves, and young men would stick their tongues under their teeth for a wolf whistle until their trousers were bulging with desire that had nowhere to go. My work colleague notices it too, teaches me how to wear my shorts twisted at the hips. Ooh-la-la. Enjoy the looks, you’re young. I think of the boys on the island, I have made all of their wishes come true. I’m no longer embarrassed. The writer takes me to our first and last climb together and introduces me to 12his closest friends: two work colleagues and a childhood friend. I walk past the friend in the mountaineering shelter toilets and recognise the look in his eyes as the same one that hunts me down the city’s streets. The writer recognises it too. Recognises desire in me, a danger. That night he fucks me with his fingers and murmurs something to himself, I know he just wants me to come. His eyes are not hungry, they’re full of contempt for a woman experiencing pleasure. I’ve seen it in the eyes on our island, in the men who cannot be with women whose languages they don’t understand, or their freedom. His hand shakes. He’s tired.

We will talk about it the first chance we get, in the morning, or in two days, or five, when he gets in touch, he’s spiralling again, uncatchable. This time I am not embarrassed of the thought that he isn’t writing. I am embarrassed to be waiting, patiently, for him to send me a location. In his head, for a while now, I am not associated with love but with rescue. I am sad, and the sadness turns into rage. Like when mother scrubs the kitchen floor and breaks the mop, grinds her teeth at funerals, breaks rosaries in half, when she scrubs Kamila and me raw in the bath after olive harvest, so that our pale autumn skin turns red again, like in the summer. I suffer. I want something good for myself in this city. I work at the library and pound the keyboard. I start with the title, I whack the keys. My sister Kamila. Double space. Words, come on in.

He opens the door of his apartment, and a bottle of wine. I open up my heart. We open the subject of his impotence like Pandora’s box, all kinds of wonders leap out of it and I am in their first line of attack. I tremble, blame myself for not having extra body parts that could replace the ones that have become insufficient. It’s a long list – the scroll reaches all the way to the fountain. He cries in my 13lap. His vulnerability makes me comfort him like a baby. He tells me about his parents, they never let him out of sight, and when he almost lost his way whilst choosing a university degree, they quickly brought him back on track with many colourful goods. He tells me that a couple of years earlier, when two of his acquaintances published their novels (and they were good books, and popular at the library, I remember) and he graduated from the private university, he suffered something like a nervous breakdown. His parents gave him pills that they were taking for their own insomnia and psychosis, and then they took him to expensive treatment centres. What kind of parenting is that, I think, I don’t want them near me. Poor him. He went to therapy once, and in forty-five minutes, more or less, he’d worked everything out. He’s fine, he just has to get rid of this hatred that he feels for everyone, and everything will be great. I just want to write, he repeats. I’m sorry, I empathise, and he pulls away from me, collects himself, wipes his tears, says, what for, I am fine. Look, he doesn’t say it meanly but with ease, as if he’s on familiar ground, the only time I can’t get a hard-on is when I’m with you. I masturbate regularly. I am healthy. Let’s talk about something else. He asks me what I want for my birthday. A story. What story? The one you’d promised. A story? For you? Yes, I say self-righteously and in my local accent. What, you’re pretending you forgot?

Everything hurts and I am not well. I annoy him, he hasn’t been writing since he’s been with me, doesn’t see his friends, he’s not doing his job properly, he has no problems with fucking, the problem is when the two of us have to have hanky-panky (that’s what he calls it), and he unwittingly admits it has happened before, but it was never this bad, he needs more time alone, to feel the flow of ideas, to feel the PROCESS, to rest, to breathe, alone, silence, 14silence. I am surprised by everything he says. We’re supposed to go on a hike tomorrow. No, no, you don’t get it Mariza, he’s dumping you. I gather my things into my rucksack, put my trainers on. I sneak out so I don’t disturb his silence. I walk to the tram station. He hates me, the thought haunts me through a sleepless night, and what could I have said or done but leave. Maybe, maybe there was something I could have done … He doesn’t change his mind, there is no message. I open Facebook in the evening and find a dozen mountaineering photos. He holds his hands up in the air on the peak. It looks as if he’s holding up the clouds, having shot the lightning bolt at my heart. He has a big smile on his face. He’s replied to every comment since 3 pm. It’s hardly been half a day, and he’s already living a new life. After midnight, as soon as the app sends a notification of a wrapped-gift icon, I get my first birthday wish. Not from him.

What is this, my sister asks, who has taken an early boat from Prikomurje to the mainland, to help me. Arrange sick leave, shut the windows, tuck me into bed, wash the dishes, cook anything soupy that would start washing the guilt out of the body. I feel bad. The pain is inside my skeleton, I wobble, I cannot support itself, I fall. It’s nothing compared to the pain I’ve inflicted on the writer, imagine what I’ve done, how am I going to get through this. I feel bad, why am I like this? What is this, Kamila says again and looks at the story with her name in the title. You’re writing again, she asks and looks through the corrected, rewritten story. Oh it’s nothing, I mumble.

Kamila heals me with stories from Prikomurje. A rich returnee from the US – whose five-floor house stuck out like a fortress among our low stone houses – has died. Everyone who has money should have the right to live forever, that’s what his wife told her at the funeral. 15Imagine! Afterwards the wife wouldn’t speak to us, she went inside the house and demonstratively turned off the terrace lights. It was the first time we could see the stars since they built the house. I start to feel better.

No, no, he hasn’t come, my colleague tells me, check the computer. True, the last thing he borrowed was returned exactly three weeks ago, on the first day of my sick leave, he’s borrowed nothing since. I arrange with her that I would hide behind the shelves or in the toilets in case he turns up. At lunchtime, I manage to free myself from the terror that grips me at the desk. I don’t go towards his office, nor do I look that way, I go up to Tkalčićeva this time, to get lunch, and wander around it to Opatovina. I sit on a bench with a plastic bowl full of hot stew. I don’t enjoy it. I remember how I used to cook lentils, oats, buckwheat for the writer, so that he had enough to last him the week, so he didn’t have to worry about food, so that he could write. I miss him and I am ashamed of the thought. I pull out my phone. I make a note on it for Kamila.

How I agreed to this, I don’t know. The nordic walking group is climbing Bikčević peak on Medvednica mountain and I drag myself behind them. As I hike, I feel pain in every muscle up to my shoulder blades. I still haven’t fully recovered. The flu, I tell those who ask me what’s wrong, why I keep stopping. Aha, that’s why you stopped coming. Take it easy. The nordic group gets in the queue for food, for seats, some are already eating by the time I reach the shelter. Mariza, Mariza, they call out to me, and I cut to the front of the queue uncomfortably. Right in front of the writer who after a brief and awkward exchange, our nodes throbbing all the way from the neck to the stomach, embraces me. It’s familiar, intimate, I feel our hearts beat together, they don’t resist, they surrender. 16

The writer is lovely. The writer is the best. Fucks. Cooks. Calls me every day. Worries about how I am. He wants us to conquer the entire city in the week that we’ve been back together. We trample across Zagreb like Prikomurje children stamp on grape must. I am naive and tell him that what we have now is all I ever really want. I am, again, loved! The writer doesn’t want to be a writer anymore. The writer has spoken to his parents and wants a better job. The writer wants to become a leader of something, branch something out. He gets through several rounds of job interviews. He’s stressed. Every conversation we have quickly ends up on the topic of his CV, job applications, what he can do, who he can talk to, the panic of whether he’d get the job, the fact that he’s the best candidate, the anxiety he feels. He asks what I think about it. I am cautious. I am afraid of him.

I am afraid each time I have to say what I think, I’m afraid to think. It makes me dizzy and gives me headaches. When I talk to him I merely glance at him. I say he should do what he thinks is best. That he could save some money with a well-paid job, take some time, take a break, and write. Imagine, if I had that money, I’d write too. Have I told you about it? That in Prikomurje I have dozens of notebooks full of stories, traditions, obituaries, travel writing describing each one of the island bays. I don’t need money to write, he doesn’t listen to me. To write I need … Who cares, he waves his hand. The proposed work contract is incredible, that night we celebrate with splashes of the fountain on Ibler Square and I feel like I’ve done a good job.

Three days. After that he doesn’t get in touch for a full three days and I feel weak again. Sick. Dizzy. I am disoriented. Everything is a blur, I listen out for the sound signal at the traffic lights, rather than 17looking at the colours. I feel bad. What did I say? What did I do? I hold on to the shelves, doorknobs, look for an empty seat on the tram. Mariza, you silly head, you’re not his girlfriend, you’re his mother, washing, cooking, comforting, that’s why he can’t get a hard-on. Hate, hate, he doesn’t hate you, he hates his own weakness, that he’s not his own person, that he’s not alive, and that it’s clear to see. He hates that you’re not stupid and so he’s making you stupid. You’re better than him at everything, you know? And you do it all alone. As soon as he sees you doing things, he’s repelled at himself. That’s why the hydraulics are out of order. He knows very well who he is and what he is. He’s a fake, electric light that makes even the brightest stars fade from view. Don’t go back there, you hear me? Promise! Oh, how I have betrayed you, Kamila. How I’ve betrayed myself, for God’s sake. The writer calls, and I am flooded with fear. I don’t answer. I read about the silent treatment. My head clears. I look at the colours on the traffic lights to get home.

I, Mariza Palaversa, am not loved. I am a fool who has been offered on-and-off love, and now I’m supposed to be on an off break. And what kind of love is that, I ask the writer as we take a walk around town on our break. Love with an open door, he explains and I get distracted. I think that he’s a bad writer. That his analogy rests on bad foundations, a cliche. That our love rests on something similar, something feeble. I don’t want a break, I want love, I say fervently, enchanted. I want passion, fire, one setting the other alight as soon as we touch! You know I’m writing a love story? In it, the heroine falls in love with a writer who doesn’t write, and then she starts writing instead of him, just like she’s been doing everything for him the whole time they’ve been together. And then, wait, hang on, let me finish, she, hey, she realises … that she doesn’t … she doesn’t love him the way a woman should love a man … wait, you haven’t heard 18the end, she realises that she loves him the way a mother loves her child!

It’s summertime. The libraries are only open in the mornings, half of the staff are on holidays. In our bay the sea urchins are pulling back from the swimmers. Old women cross themselves, young men cross their legs. Prikomurje creaks with tourists. Some head for the US returnees’ house straight off the ferry. She shoos them off and suffers aloud, shouts, swears, Kamila says look at the crazy old woman. Remember that thing she said? Everyone who has money should have the right to live forever, we say in unison. Imagine! It’s summer. The time of the year for real uncountable love. Women’s magazines shimmer under sun umbrellas, there is sun cream, mirror sunglasses, phone notifications asking for help. Look at it, lighting up the screen, I think. Who’d have thought he actually meant it. He’s sitting somewhere hurt and waiting. He’ll wait a long time. Mariza, why are you staring at that phone, come into the water, it’s hot as hell. Just a moment, Kamila, I think, free, let my heart finish thumping … it’s starting to forget.

Translated by Vesna Marić

Katja Grcić

centering

you take a long time to find the right position,

ten, twenty years, maybe even longer.

you move in all the adjoining places;

check-mate the king and queen

but it remains forever unresolved.

you sit rather violently

as you read about Saturn and female sexuality.

your system growing ever quieter.

you keep turning up the heat on God to boiling

then you pour him out into voidable moulds.