4,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Imaginarium Kim

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

Ignorance is bliss, knowledge is suffering…

…until you remember your past.

Seventeen-year-old Lisa manages the laundry at the hotel between worlds.

Has always managed, in the eternity stretching backward.

Will always manage, in the eternity stretching forward.

In other words, forever. Because that’s what the worker-residents of the hotel do for the recently-dead.

But Lisa’s “forever” ends when a mysterious guest awakens terrible memories.

Buried memories.

Memories about a murder.

*

A mind-bending exploration of memory, justice, and the consequences of choices that ripple across multiple realities—where even death is not the end of one’s story.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Ähnliche

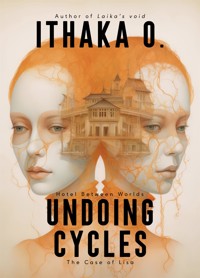

UNDOING CYCLES

THE CASE OF LISA

ITHAKA O.

IMAGINARIUM KIM

© 2021 Ithaka O.

All rights reserved.

This story is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are the products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, businesses, companies, events, or locales is entirely coincidental.

No part of this story may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without written permission from the author.

CONTENTS

Prologue

I. Today in Afterworld

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

II. That Day in Beforeworld, Once Again

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

III. Today in Afterworld, Continued

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

IV. That Day in Beforeworld, Twice Again

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

V. I, Lisa, Who Died Recently

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

VI. I, Lisa, Who Returned to Where She Began

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

VII. New Day in Afterworld

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

VIII. I, Lisa, Who Went Through

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Chapter 31

Also by Ithaka O.

Thank you for reading

PROLOGUE

One of the two women in black returns to the table with a silver tray. She places it in front of you: on it, a black candy, and a gray one, both round.

The other woman in black already sits across from you and says, “Black to move on, like all others. Gray to forget temporarily, to stay and wait—until you meet your murderer again. Whatever you do at that point is up to you, on one condition: you cannot tell anyone what happened to you. If you do, you will lose the right to find your own justice; we won’t protect you from those who envy you, hurt you, or blame you. Also remember, you cannot undo your actions and must live with the consequences for an eternity thereafter. Now, pick a candy.”

You stare at the candies. Which one would you choose?

TODAY IN AFTERWORLD

1

The sun and the moon hung on the opposite ends of the sky. Stars sprinkled the space in between. So, it was both bright and dark; bright because of the sun and dark so that the moon and stars could shine.

An impossible coexistence? No. Possible, for the sky above the hotel between worlds.

Up there, day and night met. Down here, too, two worlds met: Beforeworld and Afterworld. All around the hotel, a river flowed. Gently, never overwhelming the bustling noises from the building, its torrents splashed against the cliff that marked the edge of the misty island all around.

Aside from these movements of the river, not much else shifted around the hotel. The breeze barely blew. When it did, it only seemed to do so to circulate the damp smell of earth and moss so that the newcomers, unaccustomed to odd coexistences, wouldn’t lose their sense of reality.

What exactly lay before the island or after it, physically-speaking, the worker-residents were instructed to disregard. The mist made that guideline easy to follow. Besides, with the various celestial bodies hanging in the sky at all times, time mattered little. The order of events was trivial—or so Lisa liked to believe.

She was the laundry manager of the hotel between worlds. While some of her coworkers brooded over the beyond or near and before or after, she found it easier to not think of change. All still, all constant, with predictable influx and outflux—that was the norm, and there was nothing wrong with that.

There was a place in the world for people like her, she believed. Imagine everyone bothering themselves with intangible concepts such as religion, dreams, and ambitions. How stressful that would be! Shouldn’t there be at least some people who were content to lead the same life day in day out?

Such a lifestyle had its advantages. Lisa never felt frustrated. For frustration to occur, one had to expect something, and she never did. Didn’t expect change, didn’t expect surprise, didn’t expect meaning.

This also meant that she was never “happy” in the conventional sense. For example, she had never experienced the sensation of the heart skipping a beat when meeting the love of her life. She had also never held a newborn in her arms and realized, with overwhelming love, the complete vulnerability of that being, her immense responsibility, and the cruelty of the world all at the same time. But she surely was never unhappy either. And she didn’t complain—not about the virtual void around the hotel, and also not about the monotony.

Especially not about the monotony. Monotony, in Lisa’s opinion, was one of the most valuable things that an ungrateful soul could complain about, because the minimum requirement for monotony was peace. In war zones, you could never appreciate monotony. Even during temporary calm, you would always wonder when the next bomb would blow up the entire village. So, for a person to never have to worry about such drastic changes was an immense blessing.

These were the sorts of things Lisa contemplated when she hung freshly washed bedsheets in the back yard of the hotel on that day when all she’d known turned upside down.

The twins had helped her lightly wring out all items earlier and the still-wet heap was piled up in the giant bamboo basket that came up to her waist. Bamboo worked well for these sorts of things. Sturdy, lightweight, and well-ventilating, they were. All were crucial factors, since the bedsheets should never be wrung out completely dry. There was no point twisting and contorting the fabric to that extent. The bamboo basket didn’t add unnecessary bulk while excellently bearing the weight of the wet laundry. Lisa couldn’t imagine using a container any heavier to transport the washed items from the basement laundry room all the way here to the muddy back yard full of grass on which little droplets of dew hung perpetually.

Although the twins had offered to help her hang the bedsheets on the lines, Lisa had said it was okay, they should go play. That was the answer they’d expected, so even before she finished the sentence, they’d run off, giggling, to bother the confused newly-dead guests. Cute little creatures, those twins were. Alpha and Omega, they called themselves. Alpha, a girl with heavenly platinum blond curls. Omega, a boy with devilish charcoal hair. Six years old, both with mischievous grins.

Some guests asked if Alpha and Omega were their real names. They wanted to know where the parents were, either because they thought the names were beautiful and wanted to compliment them, or because they thought the names were hideous and wanted the parents to know that.

The worker-residents politely changed the subject whenever questions about the parents were asked. The twins, like all others who were here to stay, were eternal beings. They didn’t get older, and not because they’d stopped growing up at the age of six. Rather, because they’d always been six. They’d never been born as babies. Whoever (or whatever) had caused their existence, those parents weren’t here. Fundamentally, the twins weren’t six at all. They were older. Much, much older.

Nevertheless, Lisa couldn’t help but feel sorry for them whenever she saw them laboring. So small these kids were, regardless of how long they had existed. They smelled of childhood—of cells busier growing and replicating than aging and dying. They weren’t built to work twelve hours a day. They never would be.

Some guests had told Lisa that since she was seventeen, she shouldn’t be working this much either, it was all the same illegal child labor. But such a viewpoint seemed incredibly naive to Lisa. Of course, the guests had meant well, and apparently, some parts of the world were changing out there. But seventeen-year-olds doing no work at all? That seemed preposterous.

At any rate, it was thus that the twins ran laps around the hotel at a great speed, sometimes Alpha chasing Omega, at other times Omega chasing Alpha, while Lisa expertly wrestled with the bedsheets. When the twins rushed past the washing lines, the water-soaked bedsheets rocked back and forth. Lisa’s long black dress and white apron fluttered wildly. Supernatural beings, these children were, as were all hotel guests, to a lesser extent. None of them could be explained through modern science in Beforeworld.

Sometimes, the twins were so fast that Lisa’s hat flew off—that thin, lace-adorned piece of light white cloth—and they had to run even faster to catch it in the wind. Lisa’s long sandy hair, loosely tied, became undone and whipped her cheeks. The twins laughed and Lisa laughed too. Her hair smelled of jasmine because of the shampoo that the hotel’s owner, Lady Song, supplied for all staff. Freed from the hat, her hair rejoiced and danced. This wind that the twins stirred when they raced without restriction—this was one change that Lisa didn’t mind. When the air settled, she even wished that the twins would hurry with their lap, to reach the back yard yet again and bring some life to this quiet island.

But no, she shouldn’t think that. She shouldn’t get impatient and yearn for change. Monotony, a gift. She should appreciate it. Even though the presence and the absence of the twins represented complete opposites, such opposites actually formed a cycle. And that cycle formed a small part of the larger sameness, a part of peace, and the certainty that the twins would finish their lap and come back here, then leave because nothing bad had happened.

The gong struck in the tower. Lisa looked up. At that highest point of the hotel, surrounded by a black metal fence, Old Jeremiah swung his hammer once more. And again, and again. His long white beard swayed in rhythm with his movements, becoming more irregular with each strike. Exhaustion, that was why. Lisa couldn’t hear his panting from the ground level but she didn’t need to hear to know; his chest visibly heaved up and down. He looked eighty or ninety. That poor man. Just like the twins, he was trapped in a very inconvenient age.

When Old Jeremiah had finally struck the eleventh gong, he lowered the hammer. He stumbled to a corner of the square tower and put the hammer down. It was eleven o’clock—a concept of convenience rather than absoluteness, since the sun and moon always shone simultaneously. The last gong of the “day” was at hour twenty-two. The first gong of the “day” was at hour six. Such notions kept people “on time.”

Old Jeremiah noticed Lisa’s stare. Folding both hands in front of him, he bowed at her. She hurriedly let go of the wet bedsheet that she’d been in the process of hanging, and bowed back. The bedsheet mostly blocked their views, but whenever the gentle wind flapped it back, they could see out of the corner of their eyes—the other side had not raised his or her head yet.

Only after several seconds did they finally look up and nod, her returning to her laundry-hanging duties and him beginning the laborious, time-consuming process of descending seven stories’ worth of stairs. Lisa thought this type of formal greeting unnecessary, especially because they were dealing with eternity, not just one day and also not just one time. The time spent on bowing added up. Old Jeremiah, however, insisted in his quiet, wordless manner, that this had to be done. They each were immortal beings, deserving of respect. That was his point of view. Lisa played along, mostly because refusing to bow back made her uneasy for a long period of time afterward, while bowing only created a short-term hassle.

Well, just another day at the hotel between worlds. As sunny as it could get, what with the amount of mist. Damp as always. And Lisa, as mildly content as always.

She proceeded to hang the bedsheets with great efficiency. The river splashed. Occasionally, the twins returned. They giggled and waved at Lisa. The smell of lunch cooking drifted from the hotel building. Beef stew, onion soup, and grilled vegetables today.

The hotel breathed, creaking softly, as all ancient buildings did. Some guests found such noises creepy; they feared that malicious beings lived between the walls. Lisa thought that if a building made no noise whatsoever, that would be creepier. Most of the building’s exterior was white with the exception of black metal frames around the rectangular windows, doors, and balconies. Occasionally, round windows or arches offset the stark impression. The plant decorations too. Some hung from the eaves in smaller pots; others lived in larger pots, more like trees than shrubs, and stood in a row to mark the boundaries of roads meant for guest traffic. Still, even with the organic softening effect of such plants, the overall impression of the hotel was that of geometric precision and boldness. Old, and forever sturdy. Art Deco in black and white, a guest had once commented.

A sudden gust of wind snatched the bedsheet that Lisa was holding and blew it off of her hands. Gasping, she reached out to catch it—but the wind was already carrying it to the front of the hotel, toward the entry road, the one that stretched from the edge of the cliff all the way to the entrance.

“Alpha? Omega?” said Lisa. “Catch it!”

She said so because she thought that once again, their incredible speed had caused the wind. But when she looked around in search of the twins, they were nowhere to be seen. In fact, their laughter drifted from the other side of the building.

Alarmed, Lisa hitched up her dress and sprinted after the flying bedsheet. Mud splattered her clothes and her leather boots, which was fine; this was why she wore them, not some other fancy garbs. She could hear the chatter of the guests and visitors, only separated from her by the trees in the big pots. The foliage glistened pale-green because of the lack of strong sunlight and the mist that had condensed on their surfaces. They were thick enough to block Lisa’s view of the entry road.

“I cannot possibly be dead,” a man with a deep hoarse voice said. He sounded like an old man—someone who had been using his vocal cords for decades. “Because if I were dead, I wouldn’t keep existing like this, would I? How can I be aware that I am me and be dead at the same time? Then I’m not really dead, am I?”

He sounded aggressive and unfriendly—mocking. Lisa shuddered. His complaint was a common one among the recently dead, but each person had a different way of expressing confusion. He sounded too mocking, as if he doubted the intelligence of anyone who disagreed with him.

Still, she really hoped that the foliage would catch the bedsheet because, well, the last thing any guest of this hotel needed was a bedsheet attack. Not that the guests had any choice in the matter of staying here; this was the only hotel between worlds as far as Lisa knew. No matter what any of the staff did—undercook the stew, hammer the gong at the wrong time of the day, throw bedsheets at them—the guests had no choice but to stay until they were allowed to leave. Still, Lisa meant no trouble, none at all, even for the man who mockingly denied his own death. Some people simply expressed their frustration through anger. Moreover, understandably, a recently deceased person must be traumatized enough; no such person needed additional surprises. Please, bedsheet, stop right there. Please, wind, stop carrying it—

Another gust of wind blew into Lisa’s face. The entire building sighed. Lisa blinked in confusion because with such an exhale, the hotel surely had to shrink in size. But it couldn’t have actually sighed. Or could it?

For a moment, it looked as if the bedsheet had stopped, unable to decide whether it should proceed away from Lisa or retreat toward her. Lisa stared up at it with an open mouth. How strange, even for the island for in-betweens. The two different winds were competing in a tug of war. Instead of consisting of one mass of air, they were pulling on the bedsheet in opposite directions for the briefest second.

Then the bedsheet abruptly picked a direction, and to Lisa’s relief, toward her. Feeling like the final member to join the winning team in a tug of war, she spread out her arms and jumped to catch the bedsheet. Her heart skipped a beat when she felt the soft wet cotton against her fingers. She hugged the sheet.

Happiness. The most happiness she had felt in who knew how long.

Lisa sighed and buried her face in the fabric. Her head spun. Perhaps she’d imagined what she’d just seen. Overworking, a guest had said once, is the stupidest thing. Work, for what, if it only makes you sick?

“I tell you, I can’t be dead,” the man with the deep hoarse voice continued on the other side of the row of trees.

“Stop repeating yourself, will you?” a familiar voice said in a cold, matter-of-fact tone. Koe, the reaper. He was in his late thirties but had existed pretty much forever, so technically, he was older than the man with the hoarse voice. “Doesn’t matter if you like it or not, you’re dead.”

“Now, Koe,” said the gentler voice of Joe, also a reaper, and Koe’s partner. He was “younger” than Koe by a decade or so. “He needs time to accept his situation. That’s all.”

“So sick of this,” muttered Koe.

“You are sick of this?” said the man with the hoarse voice. “I am dead and you are sick of this?”

“Yes, idiot. You think you’re the first person who’s complained to me that he’s dead? Most people do it, one way or another, so why don’t you stop pretending that you’re damn original and just hurry up so I can drop you off and be done?”

“He means we,” said Joe. “We’ve heard a lot of people complain, and we will drop you off. And be done.”

The man with the hoarse voice muttered something back—most likely an insult, because Koe’s voice rose in response. But Lisa couldn’t hear the rest of their conversation. She turned around to return to the washing lines; they continued on toward the hotel.

“Lisa!”

It was Omega. He waved wildly as he approached her at full speed. Lisa waved back.

“What are you doing there?” he shouted across the yard. Though a span of a quarter mile still separated them, Lisa clearly heard his voice. What an energetic child he was! Alpha waved too. Her giggle reached Lisa, as clearly as Omega’s voice.

“The sheet flew off, just like that,” Lisa shouted, unsure if her weak voice could be heard.

“Weird,” said Omega, apparently having understood her message.

Yes, weird.

The hotel creaked. Lisa stopped and gazed at it. Was it inhaling what it had exhaled earlier?

The twins rushed past Lisa.

“Bye-bye!” yelled Alpha.

“Bye-bye,” murmured Lisa.

Her black dress and white apron fluttered until the twins disappeared out of sight. This was the normal kind of wind. The winds before, the one that had taken the bedsheet from her and also the one that had returned it to her—they weren’t normal. With the troubling sense that a cogwheel in the mechanism of her monotony had shifted, rendering the entire system precarious, Lisa returned to the washing lines.

Such was the problem with happiness. Once it marked a clear “up,” a “down” had to follow. This unease, then, was the down.

Must hang the sheets, Lisa repeated in her head. Nothing ever changes here. Nothing, ever.

2

Around lunch, Lisa entered the lobby. The murmur of the hotel guests, their visitors, and staff swelled all around her. She felt safer. None of the weirdly acting, competing winds blew in here. The chandeliers glowed brightly. The fans, turning slowly and incessantly, mitigated some of the dampness from the mist so that the inside of the building wasn’t as humid as the outside.

But the separation of inside and outside defied all logic in one crucial aspect: the ceiling of the lobby was simply a continuation of the sky. The moon, the sun, the stars, all coexisted together. At first glance, you could mistake the ceiling for a hyper-realistic painting or a video recording. At a closer look, however, the lively nature of the clouds proved that the ceiling didn’t rely on meager human art or technology. The movements never looped or stopped. Just as Beforeworld and Afterworld met on this island, the inside and outside coexisted in the building. You could see the sky from the lobby, yet above that ceiling lay the second floor.

All this was as expected for Lisa. Also, the melancholy piano tune from the cocktail lounge was as expected and didn’t sadden her. Zacharias never played any piece that wasn’t in the minor scale. His was the normal kind of mournful vibe. Lisa liked that. Cheerfulness tended to offend someone; forlornness rarely did. And at a place like this, where the recently dead stayed, harmony itself mattered, more than what kind of harmony, whether sorrowful or uplifting.

Why not listen to Zach’s performance from nearby? As long as Lisa performed her duties, Lady Song didn’t care how many breaks Lisa took and how long they were. Throughout the day, whenever Lisa felt so inclined, she could chat with her friend, Mina the bartender, while listening to the beautiful music. Zach didn’t mind people talking while he played. Sometimes it even seemed as if he enjoyed being mildly and inadvertently ignored. If he had disliked the indifferent treatment, he would’ve had a hard time being a hotel lounge pianist. And not just any hotel, but a hotel for the deceased. Those folks were not known to pay much attention to anyone else but themselves.

Lisa crossed the lobby to the lounge on the right side of the front desk where the guestbook sat. She nodded as a sign of “hello” whenever she made eye contact with the guests. Most of them looked confused, sad, or angry. They rarely nodded back, and when they did, it was out of reflex, not in full recognition that someone had greeted them.

Several valets carried silver trays with heaps of cookies and offered them to the guests, spreading the pleasant scent of sugar and baked flour in the process. Sweets for the shocked. But the guests reacted to such valets in the same way they reacted to Lisa:

What? What’s this? Oh, a cookie. Yeah, I remember, there used to be cookies in Beforeworld too. I guess some things just don’t change… Yes, why not. Yes, I’ll take one, thank you.

Or:

How dare you stare at me and offer me a cookie when I am dead?

The valets wore the characteristic black and white uniforms of the hotel. The marble floor tiles were also black and white. In that scene that might seem bleak to the unaccustomed eye, the guests added sprinkles of color. Whatever they had worn at the time of death was what they were wearing now. A fire-red designer dress or faded blue jeans, for example. But the status associated with their clothes mattered little here; they were all dead the same way. That fact confused, saddened, and angered some of them extra deeply.

The hotel visitors, on the other hand, reacted more consciously to Lisa’s greeting and the valets’ offer of cookies. These were the reapers in black and lawyers in white—all, people who only visited and never stayed overnight. (Again, a temporal term of convenience, not referring to the absolute existence of “night.”) The reapers operated in pairs. The lawyers operated alone. One deceased was assigned with one pair of reapers and one lawyer. Because the hotel stood between the worlds, this was where all the reapers transitioned their deceased over to all the lawyers. Consequently, clusters of four had formed throughout the lobby. Lisa walked around each group toward the lounge.

“Don’t leave me,” an old woman muttered when two reapers in black turned away from her.

“I’m sorry,” the female reaper stopped and said softly, “we have to go.”

“Your lawyer will take good care of you,” said her partner, a male reaper, with no less softness.

“That I will,” said the lawyer.

“But I don’t like lawyers,” said the old woman, looking from the reapers to the lawyer. “I didn’t like dealing with them when I was alive, so why do I have to start dealing with them now out of all times?”

Lisa chuckled softly, as did the reapers. Only the lawyer turned red. Even when dead, some people disliked lawyers more than reapers. No escaping that.

“Reapers can only go this far, ma’am,” said the male reaper kindly.

“We only operate from Beforeworld to this hotel,” said the female reaper with equal compassion. “Lawyers are the ones who operate from the hotel to the end of Afterworld. He’ll work on your case and get you to release as soon as possible. And that’s a good thing—finding a true and complete release.”

“But… but…” said the old woman, still confused.

Once again, Lisa felt a rush of relief and gratitude at being a worker-resident of the hotel. She couldn’t imagine how the reapers and lawyers dealt with the endless questions and endless roaming. Never a home. Never a rest. In contrast, Lisa had a family of sorts here; friends who never changed.

The conversation of that group faded as Zacharias’s tune amplified with Lisa’s every step toward the lounge. But closer to the opening to the lounge, a different conversation became audible.

“Idiot thinks he can weasel his way out of death like he did with other things for his entire life,” hissed Koe.

“He’s just frustrated,” said Joe in a soft tone.

“Yeah, you know what? I am frustrated. Everyone is frustrated. I guess that’s one thing that doesn’t change in life and death. Also, where the hell is X? Isn’t she supposed to be his lawyer? Be here for the client way before a reaper gets pissed off?”

“My guess is that X already has his files, saw that he is a murderer, and tried to gather information on the victim before meeting him so she can approach the case with as much data as possible… Lisa!”

Joe beamed at her.

“Joe,” she said, smiling.

“Hey,” was all that Koe said, without a hint of a smile.

Some reaper pairs, like the one she had seen back there with the old woman, worked well together because their personalities aligned. Both soft-spoken, both hot-tempered, or both timid, for example. Other reaper pairs, like Koe and Joe, functioned as a team thanks to the sometimes-true adage that “opposites attract.”

Lisa had never seen Joe grumpy. She had also never seen Koe smiling. Snickering sarcastically, maybe. Or using his facial muscles to perform the act of drawing the ends of his lips upward to convey a smile for the other party. But not actually smiling. Yet somehow, they had worked together for as long as Lisa could remember, without requesting a new partner or circumventing such official methods altogether and eliminating the other.

Yes, there were methods to do that, Lisa had heard. You could “kill” someone who was already dead. You could also “kill” someone who had no past or future because they were eternal beings.

To be more precise, in the case of the hotel guests, their souls hadn’t released yet. (“Release” was what happened when they made the substance that used to form them available to become something else.) Those souls were still “they,” unlike the Beforeworld bodies they had left behind, which were probably decomposing and returning to dust. At the hotel, the guests were in the middle of the process of dying. They literally stood on the threshold. Their souls operated their transient bodies. They still had to cross the river, stand trial, and accept the outcome, whether they liked it or not. Then, they could fully die. So, in their case, “killing” could be as simple as checking them out of the hotel and letting the usual order continue.

With the reapers, lawyers, and hotel staff, the situation was different. No one came to claim them for a trial. Also, they didn’t have to cross the river. For them, a method to reliably release didn’t exist. But Lisa had heard horror stories—cases in which the undead had attempted to die or had been killed. Lisa hadn’t inquired about the details of how to accomplish such a task, mostly because she had never wanted to end anyone. But she imagined that it must take great energy. It was against the natural order, if such a phrase made sense in this supernatural setting.

“Came here for the music?” asked Joe.

“Yes,” said Lisa. “Are you two going in?”

“We have to wait for X,” said Koe, shaking his head in disbelief—the kind of disbelief that’s actually based on belief because if it weren’t based on some kind of acceptance, one wouldn’t be so offended. “She’s so particular about meeting where it’s bright. Last time, we were waiting for her in the lounge for hours until we realized she’d been waving at us from the lobby. Can you believe it? Someone so sharp and organized as her not making the logical decision to walk into a lounge because it’s ‘too dark’ and not only that, not even to call out to get our attention? I mean, really.”

Lisa considered the lounge lighting. It was significantly dimmer than its counterpart in the lobby. Blue, green, and purple neon lights ran the entire length of the bar counter. Not the top part (that would be too blinding for the guests sitting at the bar), but rather, on the bottom part, so that Mina’s face behind it appeared ghostly from the indirect lighting. With Mina’s black hair and her black shirt, she looked like a statue that was designed to absorb light. Only her pale face appeared to be floating in nothing.

Right then, Mina noticed Lisa’s gaze. Mina stopped in the middle of making a cocktail and waved. Lisa waved back.

“I guess it could be a bit scary,” Lisa told Koe.

“Not you too,” sighed Koe. “Look at that guy. He’s enjoying himself, and us here.”

Koe meant his deceased, who was almost buried in the darkness of the lounge. The man with the hoarse voice, Lisa remembered. Because he was the sole guest in the lounge, Lisa guessed that the drink Mina was making was meant for him.

“Drinking instead of worrying about his fate,” said Koe, staring at the man. “You gotta wonder sometimes: does karma exist?”

Lisa grinned. For all the grumpiness that Koe exhibited, he wasn’t that bad. He never left Joe alone to wait for X in the lobby, for instance. Koe could have bullied Joe into doing so, with Joe being so well-meaning. But Koe didn’t. Koe also didn’t insist that his deceased go through the same inconvenience of waiting while standing, even when he obviously disliked the man.

“I’ll bring a drink to you, if you want,” she said.

“Nah,” said Koe. “What I need is for X to get over her paranoia.”

“That’s what being a lawyer does to you,” said Joe. “You don’t trust anything anymore and you’re scared about everything. Well, not everything, but of the dark, and a client sneaking up on you and ending you.”

“Well, she’d better figure out a solution to her mental obstacle soon or she’ll have to live like that forever,” muttered Koe. “And I’ll have to get used to feeling nothing in my legs from standing too long. I considered bringing a chair from the lounge, but then, look at those people.” He gestured at the guests filling the lobby. “They’re scared already, and imagine seeing a reaper exhausted. Must make them think if we’re getting enough breaks, paid leaves, and so on and so forth, so that we don’t make mistakes while reaping people. I don’t want to worry them unnecessarily, you know? They have enough on their plates.”

“They do,” both Lisa and Joe said.

Koe was compassionate in his own way. Perhaps that was why he and Joe continued working together.

“Anyway,” Koe told Lisa, “you go along. You don’t have to listen to my reaper laments.”

“I will,” said Lisa. “If you change your mind about that drink, just yell from here. I’ll hear you.”

“Yeah, well, maybe,” said Koe with a sigh.

Then he made his facial muscles work to give Lisa a forced smile. She chuckled. She appreciated his effort.

But as she walked into the lounge, at the exact moment when her left foot landed in it, she tottered.

Koe and Joe grabbed her by each arm. Thanks to that, Lisa didn’t collapse on the floor. Soon, she recovered her balance.

“Thank you,” she muttered.

“Are you all right?” asked Joe.

“I think so.”

“What was that?”

Lisa couldn’t answer Joe’s question.

After a pause, Koe said, “This is for an eternity, Lisa. No rush. There’s no end to burnout once you spiral. Pace yourself.”

“I will. Thanks.”

They let go. Lisa waved at Mina, who worriedly looked from the bar. After nodding goodbye to Koe and Joe, Lisa carefully walked toward Mina.

“Hey, come here, sit right here,” said Mina as soon as Lisa came within talking distance, nodding toward a seat by the bar. “What was that?”

“I don’t know.” The truth was, something had pushed Lisa. A wind. But that made no sense whatsoever, for air to have intention. So Lisa simply said, “I guess I slipped.”

“Huh. Did you come for a drink or for the music?” asked Mina, nodding toward Zacharias this time.

Not paying any attention to either Lisa, Mina, or the deceased who had come with Koe and Joe, Zacharias sat by the grand piano and swayed to his own minor scale music: a waltz, several phrases functioning as the motif that recurred in slightly altered forms. Sometimes the rhythm, sometimes the harmony, sometimes the melody changed.

Lisa marveled at his ability to improvise. He never used scores. Perhaps such creativity required the insistence on showing one’s uniqueness, bordering on peculiarity: out of all staff members at the hotel, Zacharias alone wore a deep purple suit instead of black and white. The suit snugly fit his slim figure. It had been tailored to perfection. He had been “born” wearing it, with a thirty-something appearance, ready to start playing the piano immediately.

Lisa said, “I came for both. But I’ll need a drink first before I’ll be able to concentrate on any music.”

Mina’s face fell. “Are you sure you’re okay?”

For a brief moment, Lisa considered telling Mina about the bedsheet and the tugging winds, plus the wind that had pushed her at the lounge entrance. But Mina was a lighthearted soul—one that adamantly adhered to the belief that if one dwelled on unpleasant thoughts, unpleasant events were bound to occur. Mina’s question of “Are you sure you’re okay?” followed by Lisa’s honest answer usually led to Mina’s advice that Lisa should ignore what had just happened.

Personally, Lisa thought that Mina’s belief system placed too much weight and power on the individual, who was usually pretty insignificant and powerless, no matter what they thought of themselves. (What about victims of an earthquake, for example? Did such natural disasters happen because people dwelled on earthquake-thoughts too much? Lisa was pretty sure that they couldn’t conjure up an earthquake through collective worry.) But there was no reason to try to change Mina, just as there was no reason to try to change anyone else at the hotel. If Lisa wanted to talk about troubling events, she could always talk to others. Besides, Mina’s strict rule of sticking to so-called positive topics meant that Lisa could rely on her not mentioning unpleasantries. That guarantee had its benefits. And there was no other girl close to Lisa’s age that Lisa knew of.

So, Lisa simply answered, “Yes, I’m fine. Just tired.”

“No wonder. You’re washing sheets and towels all day long. Sit down, sit down.”

Lisa sat on the high chair by the bar and put her elbows on the spotlessly clean, smooth glass surface. A whiff of fresh mint and celery immediately surrounded her. How pleasant.

“Do you see that man right there?” whispered Mina. This time, she nodded toward Koe and Joe’s dead man. (She had to keep nodding instead of pointing or gesturing because never once did her hands completely stop the process of making drinks. At any given time, she separated the mint leaves from their stems, poured liquor, or vigorously shook the cocktail shaker.) “Did Koe and Joe tell you? His files say he’s a murderer.”

This turn of conversation came as a surprise to Lisa. “Since when are you interested in murderers?” she asked.

“I’m not. That’s why I said ‘his files say.’ What the files say and what he’s saying are different.”

“So he’s saying it’s a misunderstanding that his files say he’s a murderer?”

“Exactly.”

Lisa turned around to glance at the man. The lounge had just enough light to prevent guests from falling: one little bulb above each round table. This supposed non-murderer sat by a two-person table near Zach. The non-murderer had turned slightly right to have a direct view of the stage. Thus, the only illuminated portion of his features was a speck of his somehow unnaturally wrinkled left cheek. The rest of him, as well as anything outside the circle of light from the bulb, remained in near darkness, only softened by the bulb above the next table.

But Lisa had no difficulty distinguishing the non-murderer’s general posture. He had placed his forearm on the top portion of his chair and leaned back, legs spread wide in that characteristic pose of men from certain decades, as if inviting the world to witness what they had between said legs.