Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Cinnamon Press

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

Introverted and emotionally aloof, Sian can't remember what her ex-husband had been talking about, but not wanting to do as he said, she did exactly what he'd cautioned against instead. From Cardiff to Saint Vay — a four-house hamlet tucked away in a forgotten corner of ancient France — Sian gives up her stable home and job in Wales to begin a new life in a borrowed cottage, because the internet told her to. Undressing Stone is a mysterious tale flirting with the gothic as it interweaves Sian's conversations with her psychiatrist with her newly reclusive life in France. There she meets Clotilde — a strange and enigmatic sculptor who likes to work in the nude. And Sian takes with her a secret she has told no-one — not even her psychiatrist. Will her encounters with Clotilde encourage her to admit a truth she has avoided for years? And what are the consequences for Sian if she does? In a narrative that moves between caustic observation and the richly sensual, this is a novel that challenges many of our assumptions about modern life and celebrates the unconventional. A beautifully paced, told with literary skill, but always compelling novel from Hazel Manuel, author of Kanyakumari and The Geranium Woman.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 418

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2017

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Contents

Title

Copyright

Acknowledgements

About the Author

Epigraph

Prologue

Part One:

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Chapter 31

Chapter 32

Part Two

Chapter 33

Chapter 34

Chapter 35

Chapter 36

Chapter 37

Chapter 38

Chapter 39

Chapter 40

Chapter 41

Chapter 42

Chapter 43

Chapter 44

Chapter 45

Chapter 46

Chapter 47

Chapter 48

Chapter 49

Chapter 50

Chapter 51

Chapter 52

Chapter 53

Chapter 54

Chapter 55

Chapter 56

Chapter 57

Chapter 58

Chapter 59

Chapter 60

Chapter 61

Chapter 62

Chapter 63

UNDRESSING STONE

HAZEL MANUEL

Published by Cinnamon Press

Meirion House

Tanygrisiau

Blaenau Ffestiniog

Gwynedd

LL41 3SU

www.cinnamonpress.com

The right of Hazel Manuel to be identified as author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patent Act, 1988. © 2018 Hazel Manuel.ISBN 978-1-78864-032-9

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data. A CIP record for this book can be obtained from the British Library.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior written permission of the publishers. This book may not be lent, hired out, resold or otherwise disposed of by way of trade in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published, without the prior consent of the publishers.

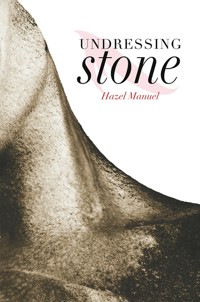

Designed and typeset in Garamond by Cinnamon Press. Cover design by Adam Craig © Adam Craig from original artwork stone figure detail: 'Scarface' © Kaplan69, Dreamstime.

Cinnamon Press is represented by Inpress and by the Welsh Books Council in Wales.

Printed in Poland.

The publisher acknowledges the support of the Welsh Books Council.

Acknowledgements

Undressing Stone emerged from the earth and the trees and the stars and the soft cream limestone of a landscape steeped in sunshine and shadow, whose vines and sunflowers flare and fold with the seasons and whose secrets hide among the stories the locals tell, and those they don’t. My novel owes its soul to a landscape as much as anything or anyone and as such I am so very grateful to have had the opportunity to immerse myself during its realisation in the beauty of rural France. I am a great believer in learning from genius, and very much enjoyed the research I did for this book. I acknowledge the influence of Auguste Rodin, Rainer Maria Rilke, Camille Claudel and David D’Angers, particularly in the development of Clotilde’s character. On a more personal note, my heartfelt thanks to Connie, Jim, Ksenya, Nancy and Ruth, fellow Francophile adoptees who spent time with me in my rural idyll, and who encouraged, critiqued and inspired my story. Thank you also to the other members of Paris Scriptorium—those who regularly or occasionally offered honest feedback—invaluable to my story’s journey. As ever I am grateful to Jan and Adam and all at Cinnamon Press for their unstinting support of my work. And of course to Pierre—qui comprend tres bien la folie de Sian. And to Willow—sydd bob amser wedi fy ysbrydoliaeth fwyaf a bob amser.

Hazel Manuel is a UK born CEO turned novelist whose writing follows on from a career in business. Having fallen in love with a French man she met in India, Hazel now lives and writes in France. Her fiction features strong female characters—complex women who are sometimes uncertain or vulnerable, but who nonetheless create spaces in which they can fully express their strength. You can find out more about Hazel and her work at www.hazelmanuel.net

I saw the angel in the marble

and carved until I set him free.

Michelangelo

Prologue

Saint Vey, Rural France

‘Never let the internet make a decision for you.’ I can’t remember now what Arwel had been talking about, but not wanting to do his bidding, that’s exactly what I did. I, Sian Evans, a fifty-something divorcee, moved from Cardiff to Saint Vay—a four-house hamlet tucked away in a forgotten corner of ancient France, perfect for farmers, old people and escapees. I went because the internet told me to. And I loved the fact that Arwel was furious.

‘Good grief Sian, how can you possibly move there?’ He had been adamant that, living alone in rural France, I’d overdose or be eaten by French savages. At least there was no chance of the first occurrence, since I’d stopped taking my medication a month before and had no plans to resume. I didn’t tell Arwel that, of course. My dear ex-husband, for reasons he would insist are motivated by my own good, would have been unimpressed. My shrink might have been less troubled—after all, it was partly his fault I went.

‘Where is home?’ That was the title of the online quiz that sent me here eleven months, three weeks and two days ago. The answer was France.You’re chic and sophisticated, the quiz proclaimed once I’d answered questions like, Which scene inspires you most? (a picture of wine and cheese on a checked table-cloth) and, Which celebrity would you date? (I didn’t recognise any of them). You can be introverted, but you enjoy good food and fine wine. You understand that life is short but you know how to savour it.I wasn’t sure about the chic and sophisticated part, so Paris was out. Rural France it was.

Home. A small word but so cavernous. Home now is my little cottage, the garden and the field behind. I’m sitting on an old wooden bench sipping a glass of wine as I typically do at sunset, the scent of wet leaves and wood-smoke suffusing the usual tirade of buzzing, twittering and rustling. The meadow is a restless sea of live things: Crickets, gendarmes, chaffinches, pigeons, a little cat grey with a bent leg. Two big hares lope past occasionally, cocking their long ears at the slightest sound, but I haven’t seen them tonight. And there are bats, small ones that fly out of the shadows at the turn of the day. All this makes it impossible to be alone. I don’t feel restless. I’m at the still centre of it all or something like that.

The sun is setting. That isn’t a metaphor, it’s that time of evening when the trees turn black and spikey and the world takes on a melancholic air, as though it regrets the futility of the day’s exertions and wants to wallow in self-pity. I like this time of day. Especially here. Strange to think it’s always sunset somewhere. When I first arrived, I used to try to work out when the sun would set in Wales. And in India. I don’t do that anymore. One sunset is all we can have at a time and it makes no sense to go chasing someone else’s. Mine, this evening, is rather a dull affair, cold and not very colourful. A glorious sunset, people say. Since I arrived I’ve been hoping for one worthy of the term, the kind that people try to be poetic about. My sun has probably sunk behind the horizon now, it’s hard to tell because it’s cloudy. Again, not a metaphor. Although, being post-menopausal, I can see how some might say I protest to much on that front.

Eleven months is more than long enough to acquire habits. I’ve acquired plenty since I arrived. And they’re not a French re-packaging of those I had in Cardiff. Back then, the first thing I’d do each morning was to dredge the night. Depending on how busy I’d been, this could take some time. Dreams, wakefulness, fears, worries, all the night-dwellers of an overactive mind would be excavated and picked over. I’d consider my discoveries, mistrustful, whatever we try to suppress will come out in our dreams. I don’t need to do that anymore. These days, on waking or on hearing the dawn chorus—the countryside is so effing noisy—I note my mind’s nocturnal output, and simply acknowledge it.

This morning, I woke with the birds, having left the shutters open. I lay in bed listening to amorous pigeons and twittery little things that were probably martins, competing with enthusiastic chaffinches, whose elaborate warbling ends with the proclamation it’s reeeeeal. Truth birds. I stretched languidly, enjoying the warmth of my duvet in the early morning chill, and thought about coffee. It’s then that it occurred to me: I was finally naked under my clothes.

Part One:

STONE

Chapter 1

‘So this is it then, you’re going.’

There’s nothing like Welsh rain, it’s cold, its grey and, I swear, it’s the wettest rain in the world. It was late spring and in spite of my half-hearted protests Arwel had insisted on driving me the twenty minutes through the deluge to the coach stop to wave me off. And to my surprise, considering we’d been divorced for years, we’d both got a bit tearful.

‘I’m going, Arwel,’ I’d replied swallowing hard and clutching my small leather backpack in front of me.

I glanced around at the huddle of teenagers in skinny-jeans, swarthy-looking men, elderly couples saying their good byes amid the diesel fumes of the already-running engine. No one was interested in me. I pulled my coat round me in the chilly morning air. Despite the hot tears which threatened to defy my fortitude, I’d thought I’d feel more. Here it was. I was moving to France. Arwel turned back to me and I pinned a bright smile on my face.

‘It feels like I’m just going on holiday,’ I said over the pounding of the rain on the bus-stand roof.

‘Maybe you are, Sian.’ He wasn’t smiling.

‘Arwel…’

I had no idea what I wanted to say to him, so maybe it was good that he cut in, his gloved hands clasping my shoulders.

‘You’ve got nothing to prove, love. If it doesn’t work out, come home.’

Arwel, I’m not your ‘love’, I felt like saying. But I didn’t. And what did he mean by ‘home’?

‘That’s very sweet of you, Arwel,’ I said, hoping my sincerity outweighed the sarcasm.

After all, that’s not what he’d said to our son at the start of his adventure, but then, everyone knows middle-aged women don’t have adventures. I was gracious and let Arwel hug me tightly, his stubble grazing my cheek, before helping me onto the coach where I shuffled along the aisle behind two pony-tailed French boys. Once installed in a window-seat, my coat folded on the seat next to mine so that no one could join me, I sat looking back at Arwel, the collar of his coat turned up, miming a telephone call and mouthing the words ‘stay in touch.’ The engine shuddered, the coach lurched forward and I watched him through the rain-streaked glass as we left our stand to join the morning traffic, his dark form growing smaller and smaller, waving at me until we rounded a corner. Effinghell, this really is it! Did he feel the same sense of sudden panic? I shoved the thought away and turned to face the road ahead. ‘I’m going to live in France,’ I repeated over and over in my mind. ‘I’m going to live in France.’

In the weeks before I’d left, Arwel had tried everything to make me change my mind. He’d invoked the gods of common sense, financial ruin, mental-breakdown, the wrath of my psychiatrist, maternal abandonment (that was the least plausible), even giving our marriage a second go (actually, that was the least plausible). Finally, for lack of any other options, he’d asked me out for a goodbye dinner.

Arwel and I had one of those rare divorces that ends in friendship. Of sorts. ‘No reason not to keep things pleasant,’ he’d said at the time. ‘For Nate’s sake at least.’ I’d agreed. The divorce had been complicated, but not in the traditional sense—our house, our finances, our son—already a man, all were easily divided or incorporated into a new reality. It was complicated because I had no grounds for divorce.

‘You’re going to have to give me something to work with here, Sian,’ my solicitor had said.

‘But he’s been a good husband and father,’ I’d replied. ‘I’m not going to lie and cite ‘unreasonable behaviour’ or whatever you call it, it wouldn’t be right. And there’s no-one else. On either side.’ I crossed my fingers under the desk, although it wasn’t exactly a lie. ‘I want a divorce because I don’t want to be married anymore.’

Arwel did all he could to convince me to stay, but in the end—and bizarrely, having realised that nothing was going to stop me from leaving—he helped me to fabricate some woes that I cited in the ‘irretrievable breakdown’ of our marriage. ‘Just tell her I neglect you—never listen to you, always forget your birthday, never take you on holiday, that kind of thing.’ None of it was true. But it was plausible. ‘He never once remembered our wedding anniversary…’ The solicitor wrote it all down with a look of distrust and I shoved away the memory of beautiful bunches of roses or gerberas arriving at my job to the envy of colleagues. Finally it was done. I was no longer Mrs Arwel Pritchard-Ellis, but plain old Sian Evans.

Nate had been in Sri-Lanka at the time and hadn’t come home to witness the demise of his parents’ marriage. ‘I suppose it’s normal these days,’ he’d said in a terse little email. And since neither Arwel nor I had a new love-interest, it had been natural—pretty much—to maintain if not quite a friendship, then at least an amicable association.

The idea of dinner was posed as a moving to France celebration, but I knew Arwel was planning an assault. The restaurant—a new one, Italian with cautiously good reviews in spite of its clichéd menu- was crowded with Saturday night trade, but Arwel had reserved a table in a quiet corner.

‘Nice place,’ he said, glancing around at the exposed brickwork and vintage prints of the leaning tower of Pisa and the like. ‘You used to love eating out…’

‘Arwel, don’t.’

I handed him his menu and a harassed-looking waiter in a smart black waistcoat arrived to take our drinks order.

‘What say we push the boat out and have a bottle?’ Arwel said, conveniently forgetting the fact that I rarely drink more than one glass of wine. He turned to the waiter. ‘Anything you’d recommend?’

They settled on a bottle of Chianti and I nodded my assent. A burst of laughter erupted from a nearby table and we glanced over at the group of animated twenty-somethings.

‘They’re having fun,’ Arwel said.

I guessed the subtext was that we ought to as well. I looked at him. It was clear he’d made an effort. His chin was newly bald and his pale blue shirt had been carefully ironed. I thought I detected a whiff of aftershave. Oh, Arwel…

His face contorted. He always read my mind, or thought he did. Our wine arrived and we had to sit there and watch the inept young waiter struggle with the corkscrew and then get flustered about a floating piece of cork in Arwel’s glass.

‘Its fine,’ Arwel reassured him. ‘My old dad always used to say it’s good luck.’

We gave the waiter our order of pizza and salad and Arwel picked up his glass and—god help us—was about to propose a toast, when:

‘Hold on,’ I said. The smell of garlic bread was too delicious to ignore and I called the waiter back to order some along with a dish of olives to start.

‘Okay,’ I said once the waiter had scurried off. ‘Continue.’

‘Well,’ said Arwel, raising his glass once more. ‘I was about to say let’s drink to the future, whatever it may hold.’

We clinked out glasses and I took a sip, wondering if we’d have to sit through an age of small-talk or whether he’d cut to the chase straight away. The small-talk lasted until our pizzas arrived, at which point he launched in with a faltering:

‘Sian, are you sure moving to France is sensible? After all, you haven’t been well…’

Seriously, that’s his opening gambit? I started a tetchy reply but Arwel raised a hand.

‘No listen, please,’ he said. ‘It’s not long since you were seeing a psychiatrist. How can you consider moving abroad?’

I looked at him, fork poised over his salad bowl, brow furrowed, head tilted to the left. There were so many ways I could answer, but what would the truth be?

‘I’m fine, Arwel,’ I said. I put a piece of my pizza into my mouth and chewed slowly. ‘You know damn well he’s an Occupational Therapist, not a psychiatrist. And I wasn’t seeing him because I was unwell. You know that as well.’

‘But you were on medication!’

Effing hell, why do I tell him so much?

‘Sleeping tablets, that’s all.’

Alright, keep your voice down.’ He flicked a look at our fellow pizza-eaters, none of whom seemed interested in me or my sleeping pills. Nonetheless Arwel changed tack. ‘Well work then, money, how are you going to support yourself?’

I attempted to raise an eyebrow.

‘Think about your son, what about him?’

I laughed out loud. ‘Nate will be thousands of miles away whether I live in Cardiff or in France.’

What I wanted to say was I’m an adult, I’ll figure it all out. But of course, I didn’t. I suppose they were legitimate questions he was asking, anyone might have posed them, but the fact that it was Arwel doing the asking hacked me off. I looked around the restaurant at the other couples, mostly middle-aged. Do all wives feel like children or mothers, rather than simply women? I’m not his wife. Two women at a window table caught my eye and I watched them as they talked. One put a hand on the wrist of the other, leaving it there for a long moment…

‘Sian, it’s great that you’re going to France, what an opportunity, Nate has his own life abroad, you’re single, there’s nothing stopping you, have a wonderful adventure.’ Arwel could have said that—but he didn’t. People don’t like it when you do something for yourself, unless it involves making money. Even then, I’m not sure it applies to middle-aged women. What he said was:

‘Come on Sian, please. Don’t do your stone-faced thing, just talk to me for once.’

Stone-faced. I always hated it when he said that, it was as if he refused to see that any interaction has at least two participants. To be fair though, I never could talk to him. Not deeply. The answers were there in my head, but they rarely made it to my tongue. So, like countless times before, I sat there, mute, the buzz of the busy restaurant accentuating my silence as I ate pizza. Arwel, knowing that whining wouldn’t help, wordlessly ate his.

‘I’m going to rent the house out,’ I said eventually. ‘I’ve spoken to an agent and the rent I’ll get will be enough to live on—just. I’ll have to watch the pennies but my needs are pretty basic.’

Arwel raised an eyebrow. ‘Well,’ he grunted, ‘I suppose that’s one option. You’ll be one of those dreadful ex-pats who take advantage of house-prices and do nothing for the country but prop up the wine industry.’

Bastard. How I’d support myself wasn’t Arwel’s business, but it was the easiest part of the move to talk about. I took a sip of wine and imagined him cursing my mam and dad for leaving enough of an inheritance to pay off my mortgage.

‘And it’s for a year, you say. Isn’t that a bit…I don’t know, self-indulgent? I mean, most people actually work for a living. You know, contribute.’

‘Contribute what Arwel? I’ve spent my adult life working in call-centres. I’m not effing Mother Theresa.’

‘No need to get vulgar, Sian.’

Always the same. When he doesn’t like what I’m saying he criticises the way I say it.

‘Look. I know I’m lucky to be able to do this and sure, most people aren’t. But that’s the point isn’t it? I do have this opportunity. Constance and Jacques have said I can have their cottage for a year. After that they’ll be selling the place. I might not have this chance again, so why not go for it?'

Arwel—no doubt now cursing my childless aunt and uncle—refilled his glass and I shook my head as he went to refill mine. He gulped down a long glug and took his frustration out on his pizza.

‘And how will we keep in touch?’ he said, spearing a tuna chunk with more force than was necessary. ‘How will you keep in touch with Nate? Is there a phone? Internet? Will you at least give me your address, since it seems you’re hell-bent on the idea?’

I hid a sigh and took a sip of my wine. ‘It isn’t outer space, Arwel, its France. There isn’t a phone there or internet, but I have my mobile. And you can write to me, if you want. You know, with a pen and paper?’

Arwel snorted and went for a last shot. ‘Sian, people our age just don’t go off and start a new life all by themselves.’

Nearly thirty years I spent with this man. And he knows nothing about me.

Chapter 2

‘I watched someone die once. To be honest, it was a bit of a let-down.’

My closet was pretty damn packed with skeletons but that wasn’t one of them, and they weren't the reason I was seeing a shrink. There was no way those bony bastards were seeing the light of day. Technically, he wasn’t a shrink; an ‘Occupational Health appointment’ it was called.

It was almost nine months before I moved to France, the day I told Doctor Jonathon Adebowale—BSc, MD, OTR/L about the dead woman. Sitting amid his expensive aftershave fug—I bet he’d slapped more on at lunch-time—all clean-shaven and pseudo-relaxed, in spite of his stupid Disney socks, the Good Doctor was swivelling in his oversized, fake-leather chair. Worse still, he was twiddling a posh pen, which would no doubt record the salient details of the hour’s exchange—or perhaps only the salacious. It wouldn’t, of course, be an exchange, I knew that much. It would be my life flowing from his ink. I glanced at his hands, still twirling the pen, not yet committing me to paper. Did he manicure? I frowned at his neat nails.

‘I’d been sitting at home watching a film—something really long—Gone with the Wind, I think...’ I tailed off hoping he didn’t think I was a racist, but he simply nodded. ‘Anyhow, old Mrs Next-Door came banging and shouting. Turns out her friend’d had a heart attack. She was still alive when I got there, her bloated stomach was quivering. I stared at her, wedged on the floor between the fridge and a cupboard, her skirt up around her thighs. I thought about mouth-to mouth, but one look at her dribbling mouth was enough to put paid to that idea. ‘The ambulance is on its way,’ Mrs Next-Door said. I don’t know why she’d got me involved. I bent to pull the woman’s skirt down. And then we both stood there staring at the thing on the floor till it stopped moving.’

I’d spoken the words slowly enough for the Good Doctor to write it down, but he didn’t move his posh pen once.

‘Why have you chosen to tell me this?’

What a question! Uttered in his low Good-Doctor voice. Because it’s your job to listen I wanted to answer, but instead:

‘It’s okay, she wasn’t a person.’

Dr Adebowale leant forward and I caught a whiff of his aftershave—not the cheap supermarket stuff that Arwel used to wear. He balanced his Good-Doctor elbows on his Good-Doctor knees, his hands propping up his chin, and repeated his last question more slowly.

‘Okay. But. Why. Are. You. Telling. Me. This?’

Like I was a child. I breathed out hard and flicked a look towards the window where a puke-coloured blind made vague shadows of the view. I looked back at him, perched on the edge of his chair, pen poised in feigned anticipation. My heart wasn’t in this.

‘I don’t know, you asked what I wanted to talk about today. Isn’t death the kind of thing we’re meant to discuss? You know, the trauma of it and all that?’

I swear he was trying not to smile. Effing man, wasn’t that against some code of ethics? He wrote something down and, as he glanced up, I saw a big hairy mole on his neck. He ought to get that checked out. The clock was on the wall behind me, presumably so that he could surreptitiously check the time without seeming bored. I’d noticed that the first time I came. He thinks that’s clever, I’d thought. He was checking it now. Jesus, I’ve only been here five minutes!

The first time I’d seen him, I’d been expecting more of a ‘knit-your-own-chickens’ type, all muesli-coloured jumpers, bits of brown bread stuck in his beard, that sort of thing. This guy looked like he would’ve been at home in a board-room and was wearing a tie-clip to prove it. Each of the three times I’d been, he’d worn a carefully ironed shirt and a coordinating tie, his suit jacket hanging with anal resolve on a hanger by the window. A wooden one. Looking around his office, I’d seen that there were no photographs on his desk, nor on the shelves, but now that I’d clocked the tie, I realised that every fibre of him screamed ‘nuclear family’, and I imagined a matching set of humans, two big, two little, in mirror-image genders, going on healthy ski-ing holidays to the Alps.

‘You told me last week that you get days when you find it difficult to motivate yourself. That your work is suffering because of it?’

At least he’d stopped laughing at me, but I couldn’t let Dr Adebowale, BSc, MD, OTR/L get away with that. Besides, there’s only so much game-playing you can do if the Good Doctor won’t do his bit, so I threw in the towel and decided to co-operate. The story about the dead woman was boring anyhow.

‘Sort of,’ I said, getting more comfortable in my seat. At least I had an armchair. ‘I don’t think my work is suffering. I’m a call-centre worker, it’s not like people depend on me every day to do something vital, like if I were a teacher or a nurse or something. And I always meet my targets.’ Well, nearly always. ‘Okay, so I take the odd day off here and there. But I work hard. No one suffers because of it.’

Tap, tap, tap. I watched him playing with his pen and fought the urge to take it from him and put it on the desk.

‘Tell me about your days off, Sian.’

I’m convinced people think your name is a key. Like it’s a way in; that the door will swing open once they’ve used it and they can march right in. I stifled a sigh.

‘I don’t know what I can tell you, except that sometimes… I can’t.’

‘You can’t...’

‘Correct. I can’t.’

‘Why don’t you tell me about that?’

Damn him. Why don’t you? Such an odd turn of phrase. I could have listed some reasons: BecauseI don’t think you’d understand, because I don’t trust you, because it’s my private business… Or made them up if necessary: My cult leader won’t let me. ‘Why don’t you tell me about that?’ In spite of the phrase, he obviously didn’t want me to list reasons why I don’t tell him. He wanted the exact opposite. In any case, I couldn’t think of any good reason not to talk about my days off, it’s not like I did anything weird, well not really. Plus, I knew he’d write down what he wanted anyhow and presumably give my HR department some kind of report. My investigations conclude that there is nothing fundamentally wrong with Sian Evans. However, she is a highly sensitive person who would benefit greatly from being able to stay at home whenever she wants. In any case, I decided to get on with it. After all, there are worst ways of spending an hour of work-time than talking about yourself.

‘Okay, well on those days even the easiest tasks are too much,’ I told him. ‘I find myself dreading having to move… getting out of bed, getting dressed… And then I just stare at things, sort of…fixated by them. Like the moving patterns on the surface of my tea for example. Or I sit and stare at my bookshelf, not really seeing it, just sort of…being there with it…’ Once again I tailed off, and once again he nodded. I warmed to the theme. ‘I tell myself I need to move, I need to achieve something, anything, no matter how small. I might put the washing into the machine and after, I feel a kind of a reprieve as I know the cycle will last for an hour and as long as I hang up all the clothes when it’s finished, I’ve accomplished something.’

Aha, now he writes.

‘Do you feel tired on days like this?’

I considered the question. It was a reasonable thing to ask, but I wasn’t sure I could answer adequately, it’s so hard to describe a feeling. He noticed me pausing, and used it as a sneaky opportunity to write down something else.

‘No, not physically tired,’ I said. ‘Well, maybe sometimes but I don’t think that’s it. It’s like I need to…absorb.’

I was getting bored now. I flicked a glance around the room—why didn’t he have pictures on those shelves, maybe a plant or two instead of just books and box-files?—and at the ugly window-blind, behind which I could hear rain starting. I wondered what the Good Doctor would do if I got up and opened it.

‘You need to ‘absorb’ you say. How do you feel at these times?’

I looked back at him. How do you feel? It must be one of the hardest questions to answer. Dr Adebowale with his many degrees or whatever the BSc, MD, OTR/L stands for should have known that. I supposed I’d have to tell him.

‘On the days when I can’t go to work it’s because I feel…soft.’

Chapter 3

I cheated on that internet quiz. France was the obvious choice, my Aunt’s cottage was available and I spoke the language. I didn’t tell Arwel of course. I was happy to move here to his disapproval after my meetings with the Good Doctor ended.

Breakdown. What a scoff-worthy word, what am I, an old car? It was Arwel who used the term not Dr Adebowale, and it effing pissed me off.

‘Sian,’ he whined, ‘you can’t quit your job! It’s obvious things aren’t right, you’re…I don’t know, depressed or something. A lot of people have breakdowns. Isn’t that why you’re seeing the shrink?’

He’d stopped short of using that catch-all weasel-phrase ‘mid-life crisis’, perhaps because he didn’t fancy a slap.

Before I quit—quite a bit before—my manager, let’s call her In-control Carol (though her name is Jill), was getting ‘increasingly concernedabout my absenteeism.’ She’d called me into her cupboard—sorry, office—to whinge about it.

‘Sian,’ she smarmed, all shiny teeth and hushed concern. ‘Sian, I really need to know what is happening with you.’

She clearly hadn’t bought yesterday’s plumbing-crisis excuse. What is happening with me? Well, Carol, I might have said, trying not to stare at her perky boobs doing battle with the buttons on her blouse. Let me tell you. Breaths go in, breaths come out, two eyes see, two ears hear, a mouth speaks sometimes as it’s doing now, and I suppose there’s some organ action-going on, I’m hazy about the details. I’d have loved to have said that. Instead, I mumbled something about a leaking washing machine.

‘Sian, there must be something at the root of all this time off you’re taking.’

Oh please, it wasn’t that much time, it probably averaged, I don’t know, three or four days a month, that’s all. Carol, who had the precise number of days I’d missed that month (seven), was one of those spike-heel-skinny-and-efficient managers, expensively cut bottle-blonde hair, never late, never tired, never interesting. I imagined her dashing off to the gym for a quick tone-up of her perfect butt, before taking over from the nanny (of course there’d be a nanny), cooking something involving fish, (marble kitchen counters) while two blond kids coloured pictures at the kitchen table (oak), then greeting her clean-shaven husband, chit-chatting about asinine crap while eating fish and leaves, bathing the blond kids, reading to the blond kids, glass of wine while curled on a beige sofa with Mr Clean-Shaven (just one, it’s a week-day), an episode of the same puerile American TV series the rest of the planet is watching, bed, (cream duvet), give Clean-Shaven a blow-job, (spit, not swallow), scrub teeth, sleep for a full eight hours, get up the next morning, do it all again.

Envy? Of course! Did I envy the countless In-control Carols and Commanding-Carls I’d worked for? Yes! But not because of their marble work-tops or the clean-shaven husband (over-rated) or the blond kids with their above average crayoning skills (Nate is blond). No. I envy them because their lives are so effing tidy.

I looked at her boobs pointing at me from across the desk (just messy enough to suggest industry), sipping herbal-tea and arranging her face into that I’m here for you expression.

‘Sian, we can’t help you if you won’t help yourself.’

Yeah. I suppose the problem I was trying to avoid was the fact that I’d reached the two year point, almost to the day, in fact. Two years in a job seems to be my average, although I once worked for an oil company for three and a half, and for a pharmaceutical business for just over four. I speak French, you see, so I’m ‘in-demand’—even in South Wales which you might not think of as a hub of Anglo-French commerce, I generally managed to find new jobs without too much stress. That four year stint was a record. And probably a fluke. I’m good at knowing when to jump before I’m pushed, and I sensed now, facing the wrath of Carol in her cupboard that the time was nigh. Shame really, I didn’t hate the work.

Oh eff off, I wanted to say. Did she have any idea how patronising she sounded? As though she—or ‘they’ since she insisted on using the collective pronoun—had some kind of right to be supportive.

‘You must be aware, Sian, that your absence record is beginning to cause concern. Is there anything you’d like to share with me?’

Yes. I don’t know who I am. I’d have loved to answer like that, but instead I stifled a yawn.

Yesterday—the day of the ‘plumbing-crisis’ had begun in a pretty standard way. I’d woken up at the normal time, switched on the radio, listened to a bit of the news, got out of bed, showered, come back to my bedroom with a cup of tea, my hair in a towel-turban, and stood in front of the full-length mirror to dry it. Jim Naughtie was droning on—crooning on really, he has a lovely voice—about the usual impending economic doom, and I was only half-listening, thinking about what I had in the fridge that I could make for my lunch. Nothing amiss so far. I’d dropped the towel onto the bed and flicked on the hairdryer, blasting it at my upturned head, before tossing my hair over, and setting about drying the front, enjoying the scent of the apple shampoo. That’s when it happened.

There was something in the mirror, a nude female homo-sapiens, but where was I? I switched off the hairdryer and dropped it to the floor where it landed with a muted thud. I don’t know how long I stared, looking up and down the body, into the eyes. I couldn’t work it out, it was like staring at that dead woman, nothing seemed to be in there. I put my hands to my mouth and amazingly, the thing in the mirror did the same.

Plonking myself on the bed, I glanced around. All seemed normal, the wardrobe there against the far wall, the chest-of-drawers with its jumble of potions laid out on top, the wicker-chair in the corner, all solid, real, resolutely here… but on the chair…the clothes! They were empty.

All the things I’d laid out last night, the grey pleated skirt, the pale-blue jumper and cardigan set, the matching knickers and bra, the tights, everything I’d intended to occupy today... empty. I couldn’t move, I sat and stared. There was nothing in the mirror, and the clothes were all empty... Where was I?

Although today wasn’t exactly the same as the other times—it rarely is—I knew from before, that if I could start, if I could only move my legs and arms, suddenly ridiculously heavy, if I could count the things that had to be done and if it was a manageable number—no more than sixteen—then I had a chance. There was no point in telling myself not to think—the problem was in my body as much as in my head, my body which wasn’t my body, but which, if I could just start, I knew I could control...

…but this was when my heart started pounding and I felt the softness overwhelm me, when the air around me opened up with a viscous artistry, and I knew, of course I knew what I should do, but I just couldn’t…

‘Jill, I’m so sorry, I meant to tell you yesterday, I’ve got the plumber coming, could be any time, he said, so I’m going to have to stay home and wait for him.’

Somehow I’m able to hold on long enough to make the call. In-Control Carol’s irritated voice at the end of the line betrays the fact that she isn’t convinced. Again.

‘Really, Sian, this is…’

‘Sorry, Jill, better get off the phone, the plumber might be trying to call. I’ll be in tomorrow, bye.’

And so, inevitably the following day, I was summoned to the cupboard where Carol’s boobs pointed at me accusingly.

‘Is there anything you’d like to share with me?’ she’d asked.

‘I’m sorry, Jill, I’m not sure it’s anything I can discuss.’

I wasn’t lying, there was no way she’d understand. What would I say? My clothes were all empty and I had nothing to put in them? Clearly, not a good idea. She nodded into my silence and took a sip of her non-tea.

‘Of course, Sian,’ she replied. ‘I understand completely. But I think we’re both agreed, there is an issue here that we need to address.’

Chapter 4

‘What does it mean to you when you’re ‘soft’, Sian?’

There hadn’t been time at the last session for the Good Doctor to excavate my use of the term, so that’s where we’d started today. A ‘therapy hour’ I’d discovered, is not an hour at all but forty five minutes. Isn’t that against some trade-description law? It’s just as well I wasn’t the one forking out for these visits. On the other hand, it did mean that I was getting paid leave on ten Friday afternoons so, all in all, not the worst result.

‘We value you, Sian, as an important part of the team,’ In-Control Carol had said, leaning forward in her seat and sounding like a recruitment brochure. I knew what she really meant: The European section is already struggling and you’d be hard to replace. ‘So we’ve booked you a series of sessions with an excellent Occupational Health specialist to get to the root of your…issue.’

A shrink, in other words. Important part of the team my eye, as my Aunt Constance used to say. Just because I dealt with customer issues in French didn’t detract from the fact that I was a call-centre operator, not the effing Managing Director.

‘What does it mean to you when you’re ‘soft’, Sian?’

Despite my best intentions not to, I rather warmed to Dr Adebowale. His attempts not to laugh at my BS told me he knew what he was doing, even if today’s socks did feature Tom and Jerry. Still, I still wasn’t about to capitulate.

‘I don’t know what it means, sometimes I’m just soft,’ I muttered. Not the most helpful reply in the world, but despite the fact that I liked him, I really didn’t care. Or at least that’s what I told myself. The Good Doctor seemed not to care either because he just sat there looking at me. I broke first.

‘Okay. Well when I feel soft it’s not…it’s not like I’m sad as such. And I’m not emotional either. Well, there is emotion, but not one that I can name… it’s just…being soft.’ There, let him analyse that.

Last time I’d phoned in sick, it had nothing to do with my empty clothes or reflection. I just couldn’t face the thought of having to talk to people. The day had started off like the last one, Jim Naughtie doom-mongering on the radio, cup of tea, shower. But in the shower-cubicle—this honestly happened—I couldn’t move. I stood there for a good twenty minutes, the hot water washing over my reddening skin, and I couldn’t bring myself to get out. When I eventually managed, I stood on the bathroom mat, steam rising off my body, feeling something close to panic at the thought of going into work. I’d rather volunteer to clean the office toilets if it meant being alone. So yeah, I left the usual message, this time fabricating a migraine as the reason I wouldn’t be coming in.

There goes the eyebrow, the left one, jerked a full half an inch higher than the other. How do people do that? Actually, I wanted to know about being soft, myself, just for interest’s sake. I mean yeah, I function, I manage my life, I cope. To all intents and purposes I’m a pretty normal kind of person. Aren’t I?

‘The thing is,’ I told him, ‘I can see how people might think it’s just a way to get an extra day or two off work. After all, who wouldn’t like a bit of time to themselves at home, to do whatever they liked with the day. But it isn’t that. And the problem is, because it’s so difficult to be honest about it, people assume you’re sick or lazy if it happens too often.’

‘Is being honest a problem, Sian?’

Using my name as a key again. Well it wouldn’t work. A yawn caught me off-guard and I struggled to turn it into a cough. He must’ve known the answer to his own question—honesty is a problem because it has the power to break things. Arwel’s face flashed into my mind…

No. Instead of honesty, we played the game, me stifling further yawns, Doctor Adebowale flicking sneaky looks at the clock. What is this achieving? My mind wandered to what I’d have for dinner that night—lasagne perhaps—and I wondered what the Good Doctor would have. Given his manicure and the hanging suit jacket, I guessed tuna.

‘The thing is, our society isn’t tolerant of inconsistency,’ I said, throwing him a metaphorical fish. ‘Especially if you’re being paid to do a job. You’re expected to perform regularly, come what may, and if you can’t, it’s seen as weakness.’

I remembered a guy at work years ago, his name escapes me. I’d overheard colleagues sniggering about him. He’d phoned to say he wouldn’t be in that day. ‘I’m calling from under the duvet,’ he’d said, although he wasn’t sick. He’d been mocked and ridiculed and eventually fired.

‘You can’t phone in and say ‘I won’t be in today, I feel soft.’ You either have to force yourself to arrive as usual and do your best to hide your state of mind. Or else lie and pretend you have a more acceptable reason for not showing up. Like a bad back or food poisoning or something.’

There we are, reasonable, rational, logical. It was pretty much the most I’d said to the Good Doctor in one go and I thought I’d wrapped the problem up quite nicely. You’re right, Sian, he should have said, the problem isn’t you at all. I’ll talk to your HR department. He didn’t say that, although he did nod throughout my explanation and it seemed he was agreeing with me until:

‘I notice you use a lot of words with negative overtones, Sian.’ He picked up his notes—which were surely infused with his posh aftershave—and read from them: ‘Society isn’t tolerant,’ ‘can’t perform regularly,’ ‘weakness,’ …

Effing Doctors! I cut him short before he could complete the character assassination.

‘To be frank, Doctor Adebowale, and with respect—I don’t think I am weak. It’s true, sometimes I have no idea how I’ll keep going until retirement. But I’m pretty damn sure I’m not the only one who feels that from time to time. And the fact that I do keep going surely makes me strong, not weak.’

‘Are you sure you have to ‘keep going’ as you say?’

Right, because I’m a millionaire and can stop work whenever I like. What an entitled fool. I didn’t dignify his question with an answer. That didn’t deter him.

‘Sian, you also used the words ‘hide,’ ‘lie’, ‘pretend’. Is there something else you’d like to share with me?’

Chapter 5

The day we talked about my wedding, I’d gone home and dug out the old photograph album. All those guests with smiling faces I hadn’t seen in years, decades in some cases. Some of them were dead now. I looked at Grandfather John, already in a wheelchair, cleanly shaven, which looked odd on him, suited and booted as he’d have said, but resolutely trilby-hatted as always. And there were my godparents, Dyffyd and Elin, chosen, so the family mythology goes, because they were the richest friends my parents had. My old mam denied that, of course. ‘Good Christians,’ she insisted. ‘That’s why we asked them.’

I turned the page and smiled at the meringue I was wearing, remembering the day I’d gone to choose it with Mam in Bridal Creations down the old high street.

‘Takes your breath away, doesn’t it?’ the wedding-shop lady had said. ‘Look at that tiny waist.’

My waist has never been tiny, the old bird was clearly doling out her well-rehearsed patter in the hope of a sale, but I liked the gown. I’d turned this way and that in the full-length mirror, trying the veil at different heights, wondering who on earth that shy-looking princess in the mirror was.

‘What do you think, Mam?’ I’d said.

My mam nodded. ‘Beautiful,’ she’d replied. I’d heard something else in her voice.

The weeks leading up to the big day had passed in a blur of florist visits, phone calls to the caterers, panic when they lost our booking, serious chats with the priest—in those days you had to convince him you were worthy of being married under his auspices—and indecision over the cake. ‘Does anyone keep the top tier for a Christening these days?’ I’d asked. ‘They do if they’re traditional,’ Mam had replied. I kept mine, but I’ve no idea what happened to it.

It rained the morning of the wedding and, throwing back the curtains, up early and full of incredulity that the big day had finally arrived, I nearly cried with disappointment. But by eleven the sun had made a cautious appearance and at three it was sunny enough not to shiver through the photographs. I looked at them now, me grinning like a loon, looking more hysterical than happy, Dad looking stiff but proud, the trousers of his new suit too short for him by a good two inches. Walking down the aisle with him had felt strange. The forced intimacy of our linked arms, the painfully slow gait, not knowing where to look, the knowledge that both of us were squirming under the gaze of so many appraising eyes.

At the reception, I sought refuge in the buffet and managed to eat my way through most of the party, thereby avoiding too many conversations. I did dance—well, it was more like shuffling to the music, and I remember wondering whose idea it had been to book an Elvis look-a-like for the entertainment.

‘Still, it went off well, the guests all seemed to have had a good time,’ I told the Good Doctor. ‘And the family seemed happy.’

Apart from my mam. She never said a negative word, but I saw her looking moody, like there was something she was fighting not to say. Dad was halfway down a bottle of Famous Grouse with Uncle Jacques by that time, both of them waving their hands around and bellowing at each other in French. I assumed that’d hacked Mam off big-time, it was the kind of thing that would. But at the end of the night she said something that I’ve never forgotten. I was exhausted and looking forward to the imminent departure of the last, die-hard guests—Dyffyd and Elin, who were deep in some inebriated debate with the purple-nosed priest.

‘I’m so tired, Mam,’ I’d said. ‘I could sleep for a week.’

She narrowed her eyes and looked at me for a long, hard moment.

‘You should have thought on that before you got married.’