32,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

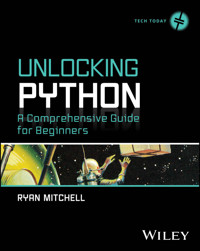

- Herausgeber: John Wiley & Sons

- Kategorie: Wissenschaft und neue Technologien

- Sprache: Englisch

A fun and practical guide to learning Python with a special focus on data science, web scraping, and web applications

In Unlocking Python: A Comprehensive Guide for Beginners, veteran software engineer, educator, and author Ryan Mitchell delivers an intuitive, engaging, and practical roadmap to Python programming. The author walks you through the vocabulary, tools, foundational knowledge, and occasional pop-culture references you'll need to hone your skills with this popular programming language.

You'll learn how to install and run Python on your own machine, get up and coding with the language quickly, and best practices for programming both independently and in the workplace. You'll also find:

- Key concepts in computer and data science explained from the ground up

- Advanced Python topics such as logging, unit testing, multiprocessing, and interacting with databases.

- Introductions to some of Python's most popular third-party libraries: Flask, Django, Scrapy, Scikit-Learn, Numpy, and Pandas

- Amusing anecdotes from the trenches of industry

Perfect for tech-savvy professionals at any stage of their careers who are interested in diving into Python programming. Unlocking Python is also a must-read for readers who work in a technical role but are interested in getting more directly involved with programming, as well as non-Python programmers who want to apply their technical skill to a new language.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 755

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2025

Ähnliche

Table of Contents

Cover

Table of Contents

Title Page

PART I: Programming

1 Introduction to Programming

PROGRAMMING AS A CAREER

HOW COMPUTERS WORK

A BRIEF HISTORY OF MODERN COMPUTING

TALKING ABOUT PROGRAMMING LANGUAGES

PROBLEM‐SOLVING AS A PROGRAMMER

NOTES

2 Programming Tools

SHELL

VERSION CONTROL SYSTEMS

INTEGRATED DEVELOPMENT ENVIRONMENTS

WEB BROWSERS

NOTES

3 About Python

THE PYTHON SOFTWARE FOUNDATION

THE ZEN OF PYTHON

THE PYTHON INTERPRETER

THE PYTHON STANDARD LIBRARY

THIRD‐PARTY LIBRARIES

VERSIONS AND DEVELOPMENT

NOTE

PART II: Python

4 Installing and Running Python

INSTALLING PYTHON

INSTALLING AND USING

PIP

INSTALLING AND USING JUPYTER FOR IPYTHON FILES

VIRTUAL ENVIRONMENTS

ANACONDA

NOTE

5 Python Quickstart

VARIABLES

DATA TYPES

OPERATORS

CONTROL FLOW

FUNCTIONS

CLASSES

DATA STRUCTURES

EXERCISES

NOTES

6 Lists and Strings

STRING OPERATIONS

LIST OPERATIONS

SLICING

LIST COMPREHENSIONS

EXERCISES

NOTE

7 Dictionaries, Sets, and Tuples

DICTIONARIES

SETS

TUPLES

EXERCISES

NOTE

8 Other Types of Objects

OTHER NUMBERS

DATES

BYTES

EXERCISES

NOTES

9 Iterables, Iterators, Generators, and Loops

ITERABLES AND ITERATORS

GENERATORS

LOOPING WITH PASS, BREAK, ELSE, AND CONTINUE

ASSIGNMENT EXPRESSIONS

WALRUS OPERATORS

RECURSION

EXERCISES

NOTES

10 Functions

POSITIONAL ARGUMENTS AND KEYWORD ARGUMENTS

FUNCTIONS AS FIRST‐CLASS OBJECTS

LAMBDA FUNCTIONS

NAMESPACES

DECORATORS

EXERCISES

NOTES

11 Classes

STATIC METHODS AND ATTRIBUTES

INHERITANCE

MULTIPLE INHERITANCE

ENCAPSULATION

POLYMORPHISM

EXERCISES

NOTES

12 Writing Cleaner Code

PEP 8 AND CODE STYLES

COMMENTS AND DOCSTRINGS

DOCUMENTATION

LINTING

FORMATTING

TYPE HINTS

NOTE

PART III: Advanced Topics

13 Errors and Exceptions

HANDLING EXCEPTIONS

EXERCISES

NOTES

14 Modules and Packages

MODULES

PACKAGES

INSTALLING PACKAGES

EXERCISES

NOTES

15 Working with Files

READING FILES

WRITING FILES

BINARY FILES

BUFFERING DATA

CREATING AND DELETING FILES AND DIRECTORIES

SERIALIZING, DESERIALIZING, AND PICKLING DATA

EXERCISES

NOTES

16 Logging

THE

LOGGING

MODULE

HANDLERS

FORMATTING

EXERCISES

NOTES

17 Threads and Processes

HOW THREADS AND PROCESSES WORK

THREADING MODULE

LOCKING

QUEUES

MULTIPROCESSING MODULE

EXERCISES

18 Databases

INSTALLING AND USING

SQLite

QUERY LANGUAGE SYNTAX

USING

SQLite

WITH PYTHON

EXERCISES

NOTE

19 Unit Testing

THE UNIT TESTING FRAMEWORK

SETTING UP AND TEARING DOWN

MOCKING METHODS

MOCKING WITH SIDE EFFECTS

NOTES

PART IV: Python Frameworks

20 REST APIs and Flask

NOTES

21 Django

NOTES

22 Web Scraping and Scrapy

NOTES

23 Data Analysis with NumPy and Pandas

NUMPY ARRAYS

PANDAS DATAFRAMES

CLEANING

FILTERING AND QUERYING

GROUPING AND AGGREGATING

NOTES

24 Machine Learning with Matplotlib and Scikit‐Learn

TYPES OF MACHINE LEARNING MODELS

EXPLORATORY ANALYSIS WITH MATPLOTLIB

BUILDING SUPERVISED MODELS WITH SCIKIT‐LEARN

EVALUATING CLASSIFICATION MODELS WITH SCIKIT‐LEARN

NOTES

Index

Copyright

About the Author

About the Technical Editors

Acknowledgments

End User License Agreement

List of Illustrations

Chapter 1

FIGURE 1.1: Variables

a

and

b

both point to the same location in memory when...

FIGURE 1.2: The number 1,234 broken down into the “ten to the thirds” place,...

FIGURE 1.3: The binary number 10101 broken down into the "two to the fourths...

Chapter 2

FIGURE 2.1: Cloning a project from GitHub

FIGURE 2.2: Chrome Developer Tools showing network requests when loading

pyt

...

Chapter 12

FIGURE 12.1: Four different types of errors shown in Visual Studio Code

FIGURE 12.2: Arguments of the wrong type are underlined (in red, in editions...

Chapter 20

FIGURE 20.1: Chrome Developer tools showing request headers

FIGURE 20.2: Talend REST API Tester

Chapter 21

FIGURE 21.1: The Django welcome page shows after installation.

FIGURE 21.2: The Django admin interface allows you to edit user details.

FIGURE 21.3: You can add instances of custom models through the Django admin...

Chapter 23

FIGURE 23.1: Pandas DataFrames display in a readable way, which makes them i...

FIGURE 23.2: Hierarchical columns show multiple column names (

mean

,

std

) bel...

Chapter 24

FIGURE 24.1: A Matplotlib scatterplot shows all samples plotted on a graph o...

FIGURE 24.2: Shrinking the size of the points and zooming in on the data can...

FIGURE 24.3: Adding colors to our scatterplot and zooming in even further sh...

FIGURE 24.4: Subplots can represent multiple dimensions of the same dataset....

FIGURE 24.5: A line graph displays average price over time.

Guide

Cover

Table of Contents

Title Page

Copyright

About the Author

About the Technical Editors

Acknowledgments

Begin Reading

Index

End User License Agreement

Pages

iii

1

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

72

73

74

75

76

77

78

79

80

81

82

83

84

85

86

87

88

89

91

92

93

94

95

96

97

98

99

100

101

102

103

104

105

106

107

108

109

110

111

112

113

114

115

116

117

118

119

120

121

122

123

124

125

126

127

128

129

130

131

132

133

135

136

137

138

139

140

141

142

143

144

145

146

147

148

149

150

151

152

153

154

155

156

157

158

159

160

161

162

163

164

165

166

167

168

169

170

171

172

173

174

175

176

177

178

179

180

181

182

183

184

185

186

187

188

189

190

191

192

193

194

195

196

197

198

199

200

201

202

203

204

205

207

208

209

210

211

212

213

214

215

216

217

218

219

220

221

222

223

224

225

226

227

228

229

230

231

232

233

234

235

236

237

238

239

240

241

243

244

245

246

247

248

249

250

251

252

253

254

255

256

257

258

259

260

261

262

263

264

265

266

267

268

269

270

271

272

273

275

276

277

278

279

280

281

282

283

284

285

286

287

288

289

290

291

292

293

294

295

296

297

298

299

300

301

302

303

304

305

306

307

308

309

310

311

312

313

314

315

316

317

318

319

320

321

323

324

325

326

327

328

329

330

331

332

333

334

335

336

337

338

339

340

341

342

343

344

345

346

347

348

349

350

351

352

353

354

355

356

357

358

359

360

361

363

364

365

366

367

368

369

370

371

372

373

374

375

376

377

378

379

380

381

382

383

384

385

386

387

388

389

390

391

392

393

394

395

396

397

398

399

400

401

402

403

404

405

406

407

408

409

410

411

412

413

414

415

416

417

418

419

420

421

422

423

424

425

426

427

428

429

430

431

432

433

iv

v

vi

vii

434

Unlocking Python

A COMPREHENSIVE GUIDE FOR BEGINNERS

Ryan Mitchell

PART IProgramming

CHAPTER 1:

Introduction to Programming

CHAPTER 2:

Programming Tools

CHAPTER 3:

About Python

NOTES

1

There are a variety of acronyms for these companies, and definitions of the “top” tech companies, and even the names of the companies themselves, change frequently. Some have also suggested replacing FAANG with MAMAA for Meta, Amazon, Microsoft, Alphabet, and Apple, reflecting the parent companies of Facebook and Google, as well as replacing Netflix with Microsoft. With this in mind, feel free to mentally replace “FAANG” with whatever definition of “popular tech giants” you see fit.

2

Yang, W., Ng, D. T. K., & Gao, H. (2022). Robot programming versus block play in early childhood education: Effects on computational thinking, sequencing ability, and self‐regulation.

British Journal of Educational Technology

, 53, 1817–1841.

https://doi.org/10.1111/bjet.13215

3

As with many of the concepts we encounter in this section, exactly how these are stored with electricity, magnets, and silicon is highly dependent on the technology and is of little importance for our purposes. But it may be helpful to think of a 1 as “charged” and a 0 as “uncharged.”

4

This is an oversimplification and ignores the existence of negative numbers. In Python, the size of integers is complicated and not something you generally need to worry about. However, the concept of numbers being a relatively large default size (often 4 bytes) does hold true across programming languages.

5

“High‐level” and “low‐level” languages will be discussed in more detail later; for now, know that a high‐level programming language is, essentially, one that is written more like plain English. It has many abstractions and features that hide details of the underlying operating system and hardware, making it easier to write programs. Python is considered a high‐level language, whereas assembly is considered a low‐level language.

6

Objects are values in computer science that have a complex structure to them. Unlike simple values like numbers or words, objects might have an elaborate schema with many attributes and functionality associated with them. For example, you might have a “user” object or a “blog post” object which contains all the information associated with that user or blog post. Don't worry about objects too much for now; we'll be revisiting them shortly and throughout the rest of the book!