Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Birlinn

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

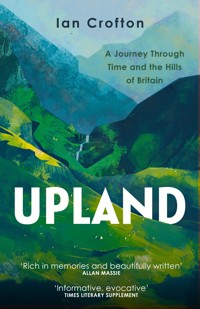

'Fascinating and lyrical . . . A beautifully written celebration of a lifelong passion' – Stephen Venables The relationship of people with hills and mountains has been complex, rich and varied – from awe and wonder to fear and loathing, from spiritual longing to peaceful acceptance. As he explores our high places, Ian Crofton conjures up those who have been there before: Neolithic axe-makers, mass trespassers, shepherds, quarrymen, botanists, poets and pioneering cragsmen and women among them. At the same time, he is ever attuned to the present moment – a flash of bright moss in a bog, the swoop of an eagle above a skyline, a winter sun sinking into a sea of cloud. Following an arc from the gentle Downs of southern England to the wild peaks of Scotland's far north, Upland combines personal experiences with a keen curiosity about the history and nature of mountain landscapes, and the people who once worked and wandered among them. The result is a meditation on the enduring yet ever-changing hills, on the transience of human experience, and on the shifts and twists of time itself. Locations included: - Chilterns (following The Ridgeway) - Malverns - Snowdon - Peak District - Pennines - Lake District - Ben Nevis - The Cuillin, Skye - Assynt (Suilven) - Cairngorms

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 466

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2025

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

First published in 2025 by

Birlinn Limited

West Newington House

10 Newington Road

Edinburgh

EH9 1QS

www.birlinn.co.uk

Copyright © Ian Crofton 2025

The right of Ian Crofton to be identified as Author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored or transmitted in any form without the express written permission of the publisher.

ISBN: 978 1 78885 775 8

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Typeset by Initial Typesetting Services, Edinburgh

Maps drawn by Helen Stirling

Contains Ordnance Survey Data

© Crown Copyright and Database Right 2004

Papers used by Birlinn Ltd are from well-managed forests and other responsible sources

Printed and bound by Clays Ltd, Elcograf S.p.A.

Contents

MAPS

INTRODUCTION

Time and the Hills

Altered uses, shifting meanings

CHAPTER ONE

Close Escapes

The consolation of small hills

CHAPTER TWO

Making Lines

West along the Ridgeway

CHAPTER THREE

Those Blue Remembered Hills

Wandering the Welsh Marches

CHAPTER FOUR

The Most Magnificent Amphitheatre in Nature

The peaks and cwms of Yr Wyddfa

CHAPTER FIVE

Reclaiming the Moors

Mass trespasses on Winter Hill and Kinder Scout

CHAPTER SIX

Hacking at the Backbone of England

Miners and quarrymen in the Pennines

CHAPTER SEVEN

Idyll or Illusion?

Lakeland before the tourists

CHAPTER EIGHT

In the Steps of the Dead

Scafell and its neighbours

CHAPTER NINE

Visions and Uncertainties

Through mist and cloud on Ben Nevis

CHAPTER TEN

The Other Side of Sorrow

Coruisk and the Black Cuillin of Skye

CHAPTER ELEVEN

A Heaven’s Revealed, in Glimpses

Suilven, a hill among waters

CHAPTER TWELVE

Shelter from the Storm

Th e Cairngorms, Britain’s sub-Arctic

AFTERWORD

The Once and Future Hills

Small lights in the darkness

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

SOURCES

INDEX

INTRODUCTION

Time and the Hills

Altered uses, shifting meanings

It was like waking up from a half sleep with the senses cleared, the self released.

– Dorothy Pilley, Climbing Days (1935), on venturing for the first time into the hills of North Wales

I’ve lived most of my life in cities. But I’ve spent much of that life dreaming of hills – remembering them, imagining them, walking and climbing among them whenever I could. Hills gift a freedom to both flesh and spirit, taking us far from the sedentary routine of school or college or office, the ordered grids of urban streets. The hills present an unbounded world, a world of possibility, a world of questions, a space in which to pause and wonder.

Lockdown after lockdown forced many of us to dig deep to preserve some semblance of sanity. I was fortunate in having rich veins of mountain experience to mine, shelves of books to browse, an open internet to plunder. If I could not walk and climb among the hills, I could look back on them, reimagine them, interrogate them. Like an archaeologist of the mind, I set out to burrow down through layers of memory into my own past, and to probe the cultural and social stratigraphy of the uplands I’d travelled through. What had happened long ago on those hills I’d loved? Who had worked there, suffered there, died there, wandered in awe among them? And how did that past inform my present, inform all of our futures? Sometimes the connections operated through the iron chain of geological or economic determination, sometimes through image and dream – resonances as ungraspable, as irresistible as the wind.

It is all too easy to think of hills simply as settings for recreation, on a par with playing fields or the local leisure centre. Politicians are prone to emphasize the amenity value of hills, monetizing this value in terms of benefits to both physical and mental health, which, if kept in good order, maintain productivity, boost the economy, reduce the costs of medical care. Schemes are drawn up to introduce children and young people to the hills, while teachers and instructors acquire qualifications to perform this role, then tick boxes to quantify the results. There is nothing wrong with this; hills do indeed bestow great benefits to society, benefits that are all too often limited by those who, on paper, possess them – those ‘landowners’ who, as a presumed right, restrict access to the rest of us and exploit wild places for commercial gain.

But hills possess more than utility; they are not just instruments to deliver wealth, health and happiness. Just as we humans have our ways of being, so do hills and mountains. But theirs is a very different way of being, one spread over eons of time, seemingly changeless and inert, but in fact active, ever becoming: building upward as the plates of the Earth’s crust shift, diminishing as wind and water and ice break them down again. We may sometimes see human or animal features in their shapes – limbed, sinewed, veined; breasted, backed, shouldered, shinned – anatomical elements reflected in many Gaelic, English and Welsh names for individual hills, from Cìoch na h-Òighe (breast of the maiden) on the Isle of Arran to Pen y Fan (head of the peak) in the Bannau Brycheiniog (Brecon Beacons) to Saddleback (Blencathra) in the Lake District. This anthropomorphism recognizes that hills exist in the present not as eternal fixed forms but as mutable entities, as mortal as humans, albeit existing over vast expanses of time. What we see are single film-frames of imperceptibly slow geological processes, processes that interconnect with the much quicker living world that cloaks them – mosses, grasses, fungi, flowers and trees; butterflies, moths and birds; lizards and frogs, voles and hares and deer and humans – all growing, dying, decaying, regenerating – flickering in the blink of a mountain’s eye.

Plants and non-human animals all have their ways of being, though we can do little to know them beyond describing them in our own terms, deploying the terse, precise metaphors of science. The exception is the human – our own – way of being, but even that, in its many manifestations, takes leaps of imagination to approximate, especially if one is looking back into the past. And those leaps of imagination will only ever reveal hazy, uncertain glimmers of the past, of all those generations that have preceded us.

In pondering this book, I had a sense that walking or climbing over the hills, as I had done all my life, might provide a physical frame for my imagination to work within, perhaps releasing some fraction of the essence – or at least a whiff – of the lives lived in these places long ago. Placing my feet, swinging my legs, taking a breath, lifting an arm, grasping a handhold, as many had done in the past – such efforts might present an almost physical link with those who had been there before.

The relationship of people with the hills through time has been complex, rich and varied – from awe and wonder, to fear and loathing, to spiritual longing or peaceful acceptance. Hills have been sites of worship, spaces of elemental hostility, places where people have found ways to live amid harshness, their beings shaped by the shapes of the hills, the wind and the rain, a passing glimpse of sunshine on a summer’s day.

As I began to retrace my own walks and climbs over the decades, I became more and more aware that I had been following in the footsteps of the dead – Neolithic axe-makers high on the Langdale Pikes, legionaries marching the Roman road along the ridge of High Street in the Eastern Fells, Mercian warriors guarding Offa’s Dyke down the spine of the Welsh Marches. Later came the miners and quarrymen, the shepherds and the drovers, the poets and painters, the geologists and botanists, seeking profit or inspiration or enlightenment. More recently, people came to the hills simply to refresh their bodies and their minds by testing their muscles and their nerves in high places, places that raised them above the gloom and graft of their daily lives. For the hills are beyond all else places that unleash the spirit, sharpen our sense of beauty and potential, even as we pant up their flanks, struggle through sleet and storm, gaze through space as ridge recedes behind ridge into an ever-enticing, unfocused far horizon.

For the most part, our higher hills have not been places to live, or make a living. Scores of dead generations dwelling in the lowlands saw hills and mountains as distant, dangerous, unproductive places, inspiring nothing but dread. A few defied the hostile upland environment, with its thin soils, its treacherous crags and frequent storms. Farmers scraped a livelihood from hardy breeds of sheep and cattle that could survive on the scant hill grazing. Desperate to provide for themselves and their families, miners braved the dangers of flood and rockfall to hack at veins of metals such as copper and lead that ran through the rocks, while quarrymen drilled and blasted mountainsides for slate and limestone.

*

Thousands of years ago, a small band risked their lives to venture up to the rugged heights in search of one of the most sought-after materials of their time. This material may have derived much of its value from the perilous place it came from, a peak poised between heaven and earth, a conical summit high above Langdale in the Lake District, where on summer nights lightning might strike and briefly light up the darkness. Pike o’ Stickle was the location of one of Britain’s earliest industrial sites, busy turning out product more than 5,000 years ago. The product of this factory was the key tool of the Neolithic, a tool that helped to clear the forests for agriculture: the stone axe-head. The axeheads from Pike o’ Stickle were made of greenstone – what geologists describe as ‘epidotized tuff’: volcanic ash that has been compressed into a dark rock as hard as flint. These greenstone axeheads were so valued that they were traded across Britain, from Scotland to the south coast of England. Many were never used, but preserved in their pristine, polished state as symbols of status and prestige.

When, on an inclement autumn day, I set off to find this early industrial site, I found myself just below the rocky cone of Pike o’ Stickle, peering down a gully that steepened as it descended so I could not see its foot. The gully was hedged in on either side by broken crags. Far below, Mickleden Beck wandered lazily through the level meadows of Langdale’s valley floor. Down there it was a place of pastoral peace. Up here, with the wind whipping my face, it was a savager, more provisional world; a place to visit but not to settle.

Tentatively I began to descend the gully, my boots kicking up rushes of dust and gravel. On either side of the pale, worn line down the middle of the gully there were piles of larger, darker stones, mingled with smaller, sharper shards. I cautiously stepped among them, my eyes scanning the confusion of countless chaotic shapes. Amid the entropy of a disintegrating hillside, I was looking for a tell-tale sign of intent, of human handiwork. I knew I was surrounded by the remains of a prehistoric axe factory, and with that knowledge I could just make out the stepped terraces made by the Neolithic miners as they quarried blocks of greenstone from the steep crags and toppled them onto the screes below. Here they were broken up, and likely pieces roughly hewn into the shape of an axe-head. The air would have been thick with the thud and crash of collapsing rocks, the sparks and sulphurous smell of stone falling on stone, the clack and tinkle as craftsmen knapped and chipped.

Langdale greenstone is no more effective than flint as a material for axe-heads. So why did it acquire its enhanced status? Perhaps it was its place of origin that gave it such prestige. This was a rock carved out of mountains that reached up into the sky, mountains of no use to people who sustained themselves by farming, mountains rent by cliffs and battered by storms, where humans only ventured at their peril. Was there some sense that up there, on those savage heights still touched by the sun when the lowlands were plunged into darkness, that up there the human world of daily struggle and seasonal routine somehow interpenetrated and drew strength from an otherworld, a timeless space inhabited by ancestral spirits and unknown powers?

*

A hilltop could be a place where you might encounter a bolt of lightning or a god, witness a celestial conjunction, bury your dead. From a high vantage point, you will be the first to see the sun rise, the last to see it set. The sun gives life; the dark brings cold and the threat of predators.

The top of a hill is a place to spot game on the plains below, or an approaching enemy. It can become a place to take refuge, where you can defend yourself and your kin with ramparts and ditches and the one-way pull of gravity. Once you are surer of your power, it is a place from which to command and control the surrounding lands, sending out your warriors to coerce and destroy. There is always a downside, though. On a summit you will be more exposed to the elements, to rain and wind and storm.

The top of a hill is not necessarily a climax, a dead-end. It may be the way to somewhere else. In the days when the low ground was either impenetrable forest or impassable marsh, a ridge of well-drained hills provided a means of travelling long distances, without becoming tangled in undergrowth or mired in mud. Upland ridges were a key component in the network of ways by which communities made contact with each other, both for trade and for cultural and social exchange. In southern England, such prehistoric routes as the Ridgeway, or the ancient tracks along the South Downs, are lined with sites that may be expressions of spirituality or power or both, from stone circles and burial mounds to giant figures of men or horses carved out of the chalk. Such monuments suggest that journeys were made for reasons other than mere commerce.

The people who followed these ways and built these monuments were not just passive dwellers in the landscape. These people helped to shape the terrain, both physically and in the collective imagination. Hills and hollows, streams and rivers, woods and wetlands, lakes and shores, all held meanings that we can now only guess at. For our predecessors, these forms and features became the ground of their being, wired into their minds, woven into their lives. Without this shaping, the land would have remained untamed, other, hostile, dangerous, without meaning, frighteningly limitless.

One such shaping is found a few miles northeast of the site of the Langdale axe factory. Castlerigg Stone Circle was constructed about 5,000 years ago, on a low plateau of glacial till surrounded by mountains, near the present-day town of Keswick. Castlerigg acts as an amplifier and a lens, its large stone uprights both echoing and focusing the great peaks that ring it – Grasmoor and Grisedale Pike, Skiddaw and Lonscale Fell, Blencathra, High Seat and Helvellyn. Here we are, the stones seem to say, in the heart of the mountains, a circle in the centre of a circle of hills, themselves surrounded by the great circle of the sky. Walk around us as you look, look around you as you walk. The stones form a frame, directing you towards the quiet power of nature: the rocky musculature, the solidity and permanence of the fells. Castlerigg, at the junction of several valleys, may have marked the intersection of trade routes, but it must have been more than just a marketplace. Our modern financial centres, from Manhattan to Singapore to Canary Wharf, might be as showy, relatively speaking (in relation to the wealth available), but their material function outweighs their show, display being a by-product of buying and selling. At Castlerigg and other such megalithic sites it is difficult to see why our predecessors would have gone to the enormous effort of erecting arrays of such massive stones merely to mark the location of the equivalent of a shopping mall or a trading floor. Such sites must have possessed a greater significance. They would have been places where different groups met and intermingled, perhaps a neutral ground where people could celebrate what they shared, whether it be a range of beliefs or myths or stories, or a sense of time past, present and future, or a feeling for spaces beyond the human – the depths of lakes or the heights of mountains, or even the dreamscapes of stars. And as the Earth turned through the light of the sun, the shadows of the stones, like the shadows of the mountains, would rotate together, all pointing in the same direction, shortening and lengthening in unison. Perhaps in such constructed landscapes people could tread out the pattern of their place in the cosmos. We are here, their footsteps said, marking time, and while we are here, we are at the centre. And even if this generation ages, dies and returns to dust, we leave our monuments to tell of the permanence of our presence, our claim to this space. To this, the mountains around bear witness. A circle – whether of stones or fells, or the sun’s disc or the pupil of an eye – has no beginning and no end. Neither has time.

*

Time did run out, however, for the megalith builders. Some 4,000 years ago, people stopped dragging huge lumps of rock about the landscape and pitching them upright or heaving them on top of two pillars to form a lintel. The great collective efforts that had built such monuments as Castlerigg and Stonehenge faded into memory, and memory into mist. The new technologies of bronze, then iron, produced societies in which small elites held power, and led to more conflict as territories were claimed and fought over with the new metal weapons now available.

Humans were no longer part of a landscape, enhancers of the natural shape of things. They were now cogs in a hierarchy, in which the greatest goods were not wonder and collective effort, but power, martial prowess and the display of portable wealth. The land itself was appropriated as the possession of particular individuals. As people gained more in material terms, so they had more to lose. And so they went on the defensive. As the Iron Age rolled on, the landscape of Britain became dotted with hillforts.

The hillforts of the Ancient Britons proved ineffective against the Roman legions, who arrived in force in 43 ce. Over the decades that followed, the Romans pushed their power northward. The hills did not stop them. Their engineers simply drove their military roads in straight lines up and down every slope they encountered. Just as their roads forced a way through unruly landscapes with geometrical determination, so the Romans built their forts and camps – not in broadly circular shapes that followed the contours of the land, as the Britons had built their hillforts, but as squares or rectangles, paying little heed to the dictates of the local topography. Thus they imposed their will on their newly conquered province.

In Britain, the Romans chose to draw their frontiers across the lowlands between major estuaries rather than along upland watersheds – just as in continental Europe, where their eastern and northern frontiers were marked by the Rhine and the Danube rather than by the Alps. Hadrian’s Wall extends from the Solway Firth to the mouth of the Tyne, generally following river valleys, although at Crag Lough it dramatically follows the rocky crest of the Whin Sill, a sheet of dolerite that extends right across northern England. The rivers and hills of the northern Pennines and Southern Uplands might have made a more ‘natural’ frontier, and this line – from the Solway northeastward via the Esk and the Liddel Water, then along the Cheviot Hills and the Tweed to the North Sea – was broadly the border that emerged a millennium later between the kingdoms of Scotland and England.

Some years ago I set out to walk this border, and found out soon enough why the Romans preferred to cross it here and there rather than trying to maintain a fortified frontier along its length. For the most part, the border follows high-level bogs and bleak tracts of rough, heathery moorland, and much of the line, even today, is pathless. One evening, halfway along, I pitched my tent high in the Cheviot Hills looking down the shallow valley of the infant River Coquet. To the south, in the slanting evening light, I could just make out the course of Dere Street – the Roman road that extended from York to the Firth of Forth – as it descended from the featureless pass between Thirl Moor and Harden Edge. Behind my tent rose a low, tussock-covered rib, extending in a straight line up the gentle slope as far as the eye could see towards the border half a mile above me, on Brownhart Law. This rib was the rampart of one of several vast overlapping Roman military camps that had been built here, at an altitude of almost 1,500 feet (460m).

It was a balmy July evening, and I was a long way from any habitation. As a yellow three-quarter moon rose in the east, a martin darted across a corner of the sky before disappearing in the darkness. There was no sense of a troubled, violent past, although there had been many bloody raids and battles along this disputed frontier from Roman times up to the slaughter at Flodden Field, not far to the northeast. As I settled into my sleeping bag and listened to the gentle sough of the breeze through the grasses growing from the long-deserted ramparts, I was content that whatever ghosts might once have lurked here had long faded into invisibility and silence.

After the Romans abandoned Britain early in the fifth century, hills again became barriers and defences. The mysterious Wansdyke, an impressive rampart and ditch extending for miles along the Wessex Downs, is thought to have been built not long after the legions left, probably by Romano-Britons anxious to halt the spread of pagan Saxons infiltrating up the Thames Valley. The day I chose to walk a section of the Wansdyke, in the summer of 2021, was the first day for which the Met Office had ever issued a warning of severe heat. The route I’d planned passed many other ancient alterations to the landscape: earthworks, enclosures, tumuli, cross dykes, a Neolithic camp and a long barrow called Adam’s Grave. But most impressive by far was the Wansdyke itself, which I followed for some miles, mostly along the northern escarpment of the Downs looking over the Thames Valley. Up on the heights a gentle breeze sighed all day. I barely saw a soul, only clusters of newly shorn sheep under the shade of a few scattered oaks. When I at last arrived – hot, hungry and thirsty – in the deep-Wiltshire town where I was to spend the night, a man eating next to me in the pub leant over and stated, rather than asked, ‘You’re not from these parts, are you.’ The border lines across the mental map of the English may have shifted, but still stand firm.

In time, the Anglo-Saxons felt the need to defend themselves against incursions by the linguistic descendants of the Ancient Britons – the Welsh. To this end, in the later eighth century, King Offa of Mercia built his eponymous Dyke, often following high ground and broadly marking what was to become the border between Wales and England. The Anglo-Saxons, in turn, had their day when their dominion over England was overturned by the Normans, who imposed their rule from numerous castles built on hills or manmade mounds. Placing such structures on prominent eminences was not just a defensive strategy; the visibility of such symbols of power helped to keep the population in check. A similar aim lay behind the frequent erection on hilltops of gallows and gibbets, where the bodies of the executed were displayed as a warning to others.

*

The perception of hilltops as liminal places, poised between good and evil, light and dark, earth and heaven, this world and the otherworld, seems to have persisted for centuries. Cross Fell, the highest summit in the Pennines, was once known as Fiends Fell, until St Paulinus visited in the seventh century and raised a cross ‘by which he counter-charmed those hellish fiends and broke their haunts’. Perhaps those ‘hellish fiends’ reminded the Roman missionary of the squabbling, all-too-human gods that once dwelt on Mount Olympus.

Not many hills are claimed by the powers of darkness, a notable exception being the Devil’s Point, a subsidiary summit of Cairn Toul in the Cairngorms (the name is actually a bowdlerization of the Gaelic Bod an Deamhain, ‘the Devil’s penis’). However, there are many legends that attribute the making and shaping of hills to the Devil or his demons. Examples of these works include the Devil’s Dyke in the South Downs; Hell’s Lum (‘chimney’), a deep rock fissure on the south side of Cairn Gorm; and the three tops of the Eildon Hills in the Scottish Borders, a division of a single summit reputedly made by a demon employed by Michael Scot, a medieval scholar and wizard who went on to work at the court of the Holy Roman Emperor.

Not all was darkness up there, above the everyday, God-fearing world below. Adherents of earlier, non-Christian belief systems, elements of which persisted long into the Christian era, sometimes viewed hills and mountains as spiritual, even sacred. In 1794, James Robertson, minister of Callander, wrote that the ‘beautiful conical figure’ of Ben Ledi in the past had drawn ‘the people of the adjacent country to a great distance’ to its summit every summer solstice, in order, as Robertson imagined, that they might ‘get as near to Heaven as they could to pay their homage to the God of Heaven’. Robertson insisted on a single ‘God of Heaven’, but many of his parishioners may have still paid attention to a more diverse assemblage of spiritual beings: the fairies.

Fairies – assumed to be survivors of a pre-Christian other-world – were long thought to make their homes within mounds and knolls. There are several mostly modest hills across Scotland whose names incorporate various versions of sith, the Gaelic name for fairies; more prominent than most is Schiehallion, ‘the fairy hill of the Caledonians’, an elegantly pyramidal and splendidly isolated peak placed more or less in the centre of Scotland. In the past, young women dressed in white would visit the mountain every May Day bearing garlands of flowers for the fairies, who, it was hoped, would grant wishes and cure diseases.

Hills that stand out by themselves, such as Schiehallion, may have had particular spiritual significances. The triple-peaked Eildon Hills, set on their own in the broad valley of the winding Tweed, had already been the site of an Iron Age hillfort and a Roman signal station before they attracted the legend of Michael Scot and his orogenic demon. But the deepest resonance of the Eildons comes from the legend of Thomas the Rhymer (a.k.a. True Thomas), who in the thirteenth century reputedly made a number of accurate predictions about the future course of Scottish history. He was said to have acquired his gift of prophesy from the seven years he spent with the Queen of the Fairies in her home under the Eildon Hills. True Thomas, an old ballad tells us, lay on the slopes of the Eildon Hills, and then, drifting off,

A ferlie [marvel] he spied with his e’e;

And there he saw a ladye bright,

Came riding down by the Eildon Tree.

Just as Thomas fell into a dream on a hill to find his vision, so did the later medieval poet William Langland. In Piers Plowman, Langland relates how he, or his narrator, ‘slombred into a slepyng’ by the side of a stream on the Malvern Hills (another isolated set of peaks on a plain) and saw ‘a ferly, of Fairye me thoghte’.

Hills give rise to dreams and visions, mingled with stories of sleepers awaiting the time when they will be needed. Legend suggests that True Thomas still rests under the Eildons, but in most stories it is King Arthur and his knights who lie slumbering until the time comes when Britain will need them. Arthur has been placed under many hills – not just the Eildons but also Arthur’s Seat in Edinburgh, and in a cleft on the cliffs of Y Lliwedd in North Wales.

Like True Thomas and King Arthur, I too have fallen asleep on hills – once on a patch of turf out of the wind near the summit of Y Lliwedd, towards the end of a long day on the Snowdon Horseshoe that had started in mist and drizzle and ended in sunshine. Sometimes, as happened to Langland on the Malverns, the drift into vision, or at least a drowsy contentment, is partly induced by the trickle of a nearby stream. I was once lulled by such water music when scrambling apart from my companions on Slioch in the Northwest Highlands in a February’s winter spring, and was gently surprised to find my urban-bound misery had dissipated. Something similar happened to me high in Val Piantonetto, above the Rifugio Pontese in the Graian Alps, lifting the gloom that followed my parents’ deaths. Sitting alone by a stream, its waters quietly but insistently chattering down from the higher peaks of the Gran Paradiso through clumps of yellow mountain saxifrage, I found myself slowly suffused with something like peace.

Some have been wary of falling asleep on mountain tops. The Reverend Francis Kilvert recorded in his diary in the 1870s the local tradition that anyone who spent a night alone on the summit of Cadair Idris in North Wales, ‘the stoniest, dreariest, most desolate mountain I was ever on’, will be found in the morning ‘either dead or a madman or a poet’.

All talk of Fairy Queens and sleeping warriors would have seemed nothing but feckless whimsy to the hardnosed mercantilists of the early modern age. Daniel Defoe spent several years compiling A Tour thro’ the Whole Island of Great Britain (1724–7), his exhaustive survey of local resources, industry and commerce. He dismissed Cadair Idris (which he called ‘Kader-Idricks’), with the brief comment that some considered it ‘the highest mountain in Britain’. But as it had no further utility, it deserved no more words. As for the mountains of the Lake District:

Nor were these hills high and formidable only, but they had a kind of inhospitable terror in them. Here were no rich pleasant valleys between them, as among the Alps; no lead mines and veins of rich ore, as in the Peak; no coal pits, as in the hills about Halifax, much less gold, as in the Andes, but all barren and wild, of no use or advantage either to man or beast.

Defoe was actually mistaken; mining for copper and lead had been undertaken in the Lake District for centuries by the time he was writing.

Both the Lake District and Eryri (Snowdonia) were to yield another profitable product, one hacked out of the side of mountains rather than chipped away from their innards: slate. Descending from the Llanberis Pass between the Glyderau and the massif of Yr Wyddfa (Snowdon), you notice that the skyline of Elidir Fawr is incised in places with gashes, in other places unnaturally flattened. These alterations to the hillside mark the Dinorwic slate quarries, one of the largest such sites in the world, worked from the 1780s until the 1960s. As a result of years of human intervention, there is less of Elidir Fawr than once there was.

Today, Dinorwic is a strange, dreamlike world. I visited one wet day in May, descending from above. The surrounding hills were cloaked in cloud as I made my way down a steep path through dripping groves of oak, the fresh spring leaves still greenish yellow, the ground and the branches draped with the vivider greens of ferns and mosses. Peaking through gaps in this temperate rainforest, there began to appear what I at first took to be craggy hillocks. Then, as the mists swirled and parted, I could see that I was looking at vast, dark piles of spoil, many of them hundreds of feet high, composed of pieces of broken, unwanted slate. It was as if the earth had been despoiled and abandoned.

*

It was not only Defoe who regarded mountains as inimical to the civilizing, nurturing arts of agriculture and husbandry. For most people they did nothing but inspire fear and loathing. No beauty resided in them; beauty was only to be found in tranquillity, and tranquillity only in the lowlands. Mountains were ugly. Not only because they were of monstrous size, asymmetrical and hostile to human existence; they were ugly because they had no use.

In the middle of the eighteenth century, attitudes began to change. Irregularity in landscape, the element of surprise, came to be valued for its own sake, and as the subject for art. Nature did not need to be ordered into geometrical grids like a formal garden; it was to be allowed its vagaries and peccadilloes – up to a point. The idea of the picturesque was born. The picturesque was still a somewhat tame version of landscape, one controlled by the restraints of classical order, one that eschewed the terrible, the life-threatening. Some bolder spirits began to embrace huger, more dangerous spaces, thrilling at the threat of the immense, the infinite, the unknowable, eager to embrace awe and terror, even pain and anguish. And so the picturesque was overwhelmed by the sublime. It was the birth of Romanticism, and all of Europe swooned.

The tension between the classical concept of the beautiful (rational, calm, measurable) as opposed to the sublime (inhabiting only the vastnesses of the imagination) is summed up in an exchange in 1773 between Samuel Johnson and his younger friend James Boswell during their tour of the Scottish Highlands and Islands. Travelling down Glen Shiel, ‘with prodigious mountains on each side’, Boswell enthusiastically called one mountain ‘immense’ (literally, ‘immeasurable’). Johnson would have none of it. ‘No,’ he retorted; ‘it is no more than a considerable protuberance.’ Johnson saw nothing in the mountains of Scotland but a tedious absence of variety: ‘An eye accustomed to flowery pastures and waving harvests,’ he insisted, ‘is astonished and repelled by this wide extent of hopeless sterility.’

But Johnson was falling behind the fashion of his times. Among his many London friends was the poet and polymath Elizabeth Carter, a leading light of the original Bluestocking Circle. Carter’s social and intellectual life was in London, but her home was in Deal, not far from where the North Downs crash abruptly into the Channel at the White Cliffs of Dover. While ‘up in town’, she complained that she was ‘panting for breath in the smoke of London’. Only while striding the North Downs did she feel truly alive – a predilection that caused many local people to view her with suspicion. In 1762 Carter wrote to Elizabeth Montagu about one of her expeditions in the North Downs, ‘which I believe you would have admitted to be in the true sublime’. At the top of one hill, ‘in all the freedom of absolute solitude’, she surveyed the ‘immense ocean’ beneath her. ‘I found myself deeply awed,’ she wrote. ‘I seemed shrinking to nothing in the midst of the stupendous objects by which I was surrounded . . .’

It took another three decades for the sublime to find its finest voice. In ‘Lines Written a Few Miles Above Tintern Abbey’ (1798), William Wordsworth celebrates the waters of the River Wye ‘rolling from their mountain-springs’ between ‘steep and lofty cliffs’. In such wild places, where Johnson sees only ‘hopeless sterility’, Wordsworth finds a lesson for humanity,

a sense sublime

Of something far more deeply interfused,

Whose dwelling is the light of setting suns,

And the round ocean, and the living air,

And the blue sky, and in the mind of man . . .

Wordsworth is measured and thoughtful, his ear attuned to ‘the still, sad music of humanity’ he hears sounding through meadows, woods and mountains, through all of nature.

For Wordsworth, the sublime was an inner thing, a moral sensibility. Wordsworth’s friend, Samuel Taylor Coleridge, was more responsive to the otherness of the sublime, the terrifying and potentially overwhelming powers of nature as found in the mountains. There is little of this in his published poems, but there are many examples in his letters and journals. In 1802, while making a solo walking tour of the Lakeland fells, he recorded the unmediated responses of a man on his own amid a thrilling but dangerous landscape. Looking up Ennerdale Water into the heart of the higher fells, he recorded: ‘The mountains at the head of this lake are the monsters of the country, bare bleak heads, evermore doing deeds of darkness, weather-plots, and storm-conspiracies in the clouds.’

In contrast to the quiet questings of Coleridge, Sir Walter Scott was a great showman of the sublime, playing to a paying audience. In his verse narrative The Lady of the Lake (1810), set in the Trossachs, an area of lochs and craggy mountains in the southern Highlands, he begins with a hunter chasing a ‘noble stag’:

And thus an airy point he won,

Where, gleaming with the setting sun,

One burnish’d sheet of living gold,

Loch Katrine lay beneath him roll’d . . .

This is the summit as conquest, opening up vistas of the world below as if the summiteer has captured an empire and its wealth of ‘living gold’. Scott also throws in a good dose of the sublime, to titillate his readers with vicarious terror:

High on the south, huge Benvenue

Down on the lake in masses threw

Crags, knolls, and mounds, confusedly hurl’d,

The fragments of an earlier world . . .

The Lady of the Lake met with immediate success and kicked off a tourist boom in the Trossachs. This and other verse narratives and novels by Scott established a passion right across Europe for all things Highland, especially if they involved tartan, heather, sword dances and deer-stalking – with a diminished, compliant peasantry to add a little colour to the scene.

Among those swept up in the fashionable new passion were Queen Victoria and Prince Albert, who in the 1850s built for themselves a turreted extravaganza in the Scottish baronial style at Balmoral in Upper Deeside. For Victoria it was ‘this dear paradise’, and during her many visits there she ascended, on pony-back, both Ben Macdui, Britain’s second highest mountain, and Lochnagar. For his part, Albert spent much time stalking and shooting red deer – a pastime that had by then become increasingly popular among the moneyed classes, partly as an escape from the industrialized world of the cities where many of them made their fortunes, perhaps also from an urge to demonstrate that within every plump plutocrat there lurked a leaner, nobler savage.

Over the previous decades the Highlands and Islands of Scotland had been cleared of many of their people, whom the landowners calculated were not as profitable as sheep. In many parts of the Highlands, it transpired that the mountains were unable to support as many sheep as had been hoped, and many owners turned their land into ‘deer forests’ to provide shooting for wealthy visitors. Grouse moors were also established across much of the eastern Grampians, the Southern Uplands and the Pennines. Across all these ‘sporting estates’ access for ordinary people was severely restricted. Ownership of such estates leant considerable social prestige, and in the Highlands the owners saw themselves as successors to the great Highland chieftains who once ruled over these wild lands (King Charles III, the current owner of Balmoral, likes to wear a kilt whenever in Scotland; only the Royals, apparently, can wear the ‘Balmoral Tartan’). Recent research has revealed that much of the money to purchase many of these estates was derived from slavery. And if the money didn’t come from slavery, it came from rents or profits from trade and industry, and the sweat and suffering of working people. All this was screened behind the romance of the chase, epitomized in The Monarch of the Glen, Edwin Landseer’s 1851 painting of a ‘noble stag’ proudly raising his head against a background of misty, rocky mountains.

Alongside the well-heeled who went to the hills and moors to shoot for sport, there were others from the middle classes who were drawn to the mountains to pursue their professions or their intellectual interests – not only painters but also botanists, ornithologists and geologists. In the course of their pursuits, they often found themselves clambering up steep, rocky slopes. Others before them had been obliged to put their lives at risk on the heights, not for intellectual or aesthetic satisfaction, but in order to feed themselves and their families. When in 1770 the Welsh traveller Thomas Pennant visited Llyn Ogwen amid the mountains of North Wales, he saw ‘the shepherds skipping from peak to peak; . . . they seemed to my uplifted eyes like beings of another order, floating on the air’. Even more daring were the exploits of those who scrambled up and down sea cliffs in pursuit of birds and their eggs. William Daniell, in A Voyage Round Great Britain (1814–25), gives some vivid descriptions of fowlers at work on the huge cliffs of Hoy in the Orkney Islands. ‘The smallest accident may ruin them,’ he wrote; ‘the untwisting of the rope, the slipping of a noose, the friction on the rugged edge of the rock, may prove fatal . . .’

Through the course of the nineteenth century, more and more gentlemen (and some ladies) sought adventure on the crags and cliffs of Britain, exceeding in daring those tourists who undertook the somewhat pedestrian ascents, usually guided, of hills such as Skiddaw and Ben Lomond. Initially, these ‘cragsmen’ (and a few cragswomen) saw the hills of Britain merely as training for the Alps, where Britons (aided by skilled local guides) made first ascents of many of the Alpine giants. By the end of the nineteenth century, the mountains of Britain were being valued for themselves, and, as the easier paths became overfamiliar, some sought greater challenges, hauling themselves up forbidding crags by dank gullies, balancing along rocky ridges, cutting steps up steep slopes of snow.

As the love of hills spread through society, landowners increasingly resisted the incursions of the urban masses onto their upland estates. In protest, organized trespasses began in the later nineteenth century, culminating in the famous events on Kinder Scout in 1932. This eventually led to reforms and the formation of national parks, although the ‘right to roam’ still does not exist in large parts of this island.

Landowners have often complained that ramblers damage their domains, scattering litter and frightening the wildlife. In a heated parliamentary debate on access in the early twentieth century, one landed proprietor objected that ‘if people were allowed to roam about flying kites and playing concertinas there would soon be no grouse or deer forests’ left. Uplands are indeed fragile places, but it is usually commercial or sporting interests that have done the most damage, diminishing the contribution that rich biodiversity and well-functioning ecosystems can make to the health of the planet. Centuries of poor land management in Britain’s uplands are only now, slowly, being reversed. But there is a very long way to go. The hills are still widely overgrazed by sheep, while heather moors set aside for driven grouse shooting are subjected to regular burning and the killing – whether legal or illegal – of many other moorland species, from mountain hares to hen harriers. In much of Scotland, great swathes of wild land have been degraded to wet, treeless deserts by excessive numbers of red deer, maintained at unsustainable numbers for the ‘sport’ of a few wealthy shooters. Across Britain, large blocks of upland have been planted with non-native conifers such as Sitka spruce, creating monocultures among which few native species can thrive. Many upland valleys have been dammed, either to supply fresh water to the cities, or to generate electricity. In the process, villages have been drowned, and hillsides scarred with horizontal bands of barren rubble as water levels rise and fall. Hydroelectricity is certainly one way of reducing our carbon impact; another is wind energy. But dams and wind farms – often heavily subsidized by government – can spoil a vulnerable landscape as surely as can a motorway or an industrial estate. Upland scenery is a public good, all too often appropriated for private gain.

Tensions over the ownership, uses and management of our uplands continue. Some hold out for maintaining ‘tradition’, in the form of sheep farming, driven grouse shooting and deer stalking, arguing that these activities are essential to rural employment and help to preserve the landscape. Others point out these ‘traditions’ are not that old, contribute little to rural economies compared to walkers, climbers and ecotourists, turn our uplands into wastelands of seriously depleted biodiversity, and limit most people’s access to the benefits of the countryside.

Some of these issues are touched on in this book. But this is not a campaigning tract, rather a meditation on the past and present of our hills. As chapter follows chapter I trace a kind of journey, both through time – albeit in its non-linear guise – and through the island of Britain, from the low hills close to my adopted home in London to the mountains of my youth, far to the north in Scotland. I follow the great chalk ridges spreading west across southern England, then explore the hills of the Welsh Marches, and the peaks and cwms of Yr Wyddfa, then east and north again through the Pennines, the gnarly backbone of England and once its industrial heartland. The Lakeland fells, too, have their history of industry, as well as stories of travellers and poets – some of whom also ventured through the Highlands and Islands of Scotland, which became a mecca for tourists once the people who had lived there were cleared off the land. I finish my journey on the high, remote, sub-Arctic plateau of the Cairngorms, where the adventurous can find solitude and a harsh kind of solace, and where, in places at least, the native flora and fauna are beginning to recover from centuries of poor land management, policies that have favoured the interests of grandee landowners over the needs of nature.

Britain has very few wild places, and the demands we make upon them threaten the very things we treasure when we go there. Reconciling the past, present and future of our hills, discovering what we truly value, assuming a responsible stewardship – all remain continuing challenges. At the same time, we must ponder our presence among the hills. Are we exploiters, conquerors, consumers, voyeurs? Or should we live up to our responsibilities not as masters but as guardians of the land, seek to become a living part of the mountains, shine as brief, bright moments in their long journey through geological time?

CHAPTER ONE

Close Escapes

The consolation of small hills

The North Downs of Kent were the first hills I saw. They were the highest hills in the world. I knew this when I stood on them and gazed into the blue distance where the world ended.

– Frank S. Smythe, The Spirit of the Hills (1935)

On the low hill above my home in Hornsey, North London, I can on a clear day see beyond the distant dome of St Paul’s and the towers of the City to a faint line on the horizon. The mass this line defines is so smudged and far away that it pales into a haze. It’s as if it wasn’t the solid chalkland, cloaked in wood and meadow, that I know it to be, but rather something vaporous, neither of this earth, nor of the sky. I know from the map that I am looking at the North Downs. But from where I stand, they could belong to another world, a world from which I’m separated by gulfs of time and space.

I’m standing on a balustraded terrace in front of Alexandra Palace a few weeks after the world locked down. Even the North Downs, visible from where I stand, are forbidden, impossibly far away. In ones and twos people promenade along the terrace, as they would have in the Palace’s Victorian heyday, but keeping more distance. The slopes below me are busy with single people, couples, small families desperate to be out and about, in touch with the world, yet not touching it. I must, for the moment, be content with this most modest of hills, the eastern end of a low ridge extending westward to Muswell Hill, Highgate Wood and Hampstead Heath. This ridge, partly composed of glacial till (an agglomeration of gravel fragments in a matrix of clay), was the southern limit of the Anglian ice sheet, which reached what was to become North London around half a million years ago.

To the south, across the Thames, the land was left uncovered, the hills ungouged by ice. But, over time, valleys and gaps were worn by the persistent, quiet power of water. I’ve wandered up some of the tributaries of the Thames that drain off or cut through the North Downs: the Wey, the Wandle, the Ravensbourne, the Darent, the Medway. Rivers are the complements of hills. Hills rise to the sky; rivers flow, inexorably, the other way. The sides of river valleys are the slopes that shape the hills, give them height, and their heights depth. There would be no uplands without lowlands, just as there would be no light without the darkness that frames it. It is one of those linguistic ironies that, in southern England, uplands are called ‘downs’– ‘down’ in this sense coming from Old English dun, ‘hill’ or ‘high open land’.

Perhaps a place to start, before rising up into the hills, is in one of the lowest of the lowlands, amid the mudflats of the estuary of the River Medway, downstream from where its waters cut through the North Downs at Rochester. Just as in the Downs there are names for every type of landform – commons and coombes, tops and bottoms, warrens and holes, hangers and heaths – so those flattest of flatlands, the estuaries, have their own special features: oozes and saltings, creeks and reaches, tidal islands and treacherous marshes.

One cold spring, over the course of a number of scattered days, I walked with a couple of older neighbours up the Medway through the North Downs to the High Weald and the Ashdown Forest. We started at Swale station, just short of the Isle of Sheppey, and began to make our way upriver along an embankment that kept the sea from the lower-lying land of Ferry Marshes. In the distance, looking up the Medway through a thin mist, a line of pylons strode across the landscape. Downriver stood the giant cranes and liquid-gas storage tanks of the Isle of Grain. Smoke or steam drifted lazily up into the sky. Closer by, the glassy water was coated with swirls of livid green scum and dull sheens of oil, edged with oystercatchers, shelduck and discarded tyres.

Near Slaughterhouse Point a sign told us that this was private land and that there was no footpath – despite the fact that we were on a public right of way. Large heaps of white ash smoked – some kind of waste disposal was at work – and a man on a tractor confirmed we could not pass. The Medway was once used for other forms of waste disposal. Hundreds of convicts were formerly held in prison hulks anchored in the estuary, and some of their bodies were dumped on an area of tidal marsh called Deadman’s Island. Every now and again, as the tide shifts the mud, human bones still come to the surface.

On the second day of our journey, we traversed the interlocking confusion of three of the five Medway Towns – Gillingham, Chatham and Rochester. In the past, this built-up stretch of the river was home not only to a large naval dockyard but also to several army barracks. On the inland side, by the village of Borstal (now home to a young offenders’ institution and an adult prison), the viaduct carrying the M2 over the Medway marks a clear boundary between town and country. If we were to continue following the river from here to Maidstone, we’d be winding along endless meanders, through marshes, by sewage works, around the fenced perimeters of industrial estates. A more attractive alternative was to cut the corner and follow the path along the crest of the North Downs. And so we escaped from the estuarine flatlands up onto the heights.

At the start of our path there was an inauspicious sign. It read:

NO TRESPASSING.VIOLATORSWILL BE SHOT.SURVIVORSWILL BE SHOTAGAIN.

Things improved after that. As the hum of the M2 grew fainter, the path took us gently upward onto Nashenden Down beside a hedge of hawthorn in bright white flower. On the other side of the path, a meadow drifted downward towards the river. Overhead, the sky was filled with lark song. Once up on the top of the escarpment, we looked out across the Weald, a wide, rolling landscape of woodland interspersed with fields, some pale green with young hay, others gold with buttercups or the acid yellow of oilseed rape. The smooth, wooded slopes of the Downs on the far side of the Medway were cut by the wide, white scar of an old chalk quarry. It might have been the remains of a vast fortification line on the Western Front. Here and there at the side of our path poppies grew from the broken ground.

To the west, the gently scalloped ridge of the North Downs receded, fold behind fold, marking the northern edge of the undulating plain of the Weald, like a coastline above a vast inland sea. Somewhere along that edge, unseen in the valley of the River Darent as it cuts through the Downs between the M20 and the M25, lies the village of Shoreham. It was in Shoreham in the 1820s and 1830s that the painter Samuel Palmer spent nine years making his visionary landscapes, while living in a run-down cottage nicknamed Rat Abbey. In Palmer’s pictures the Downs become a hallucinatory Eden where it is always spring or summer, a prelapsarian garden in which trees are plump with blossom, and the moon looks down on steep-domed hills thick with ripening corn. The boles of old oaks are swollen with unspoken histories, woolly sheep rest beneath billowing clouds, boughs bend under the weight of fruit. Everything is pregnant with undelivered tension.

In the end, Palmer was drained of vision and returned to London. Perhaps the increasing unrest among agricultural workers – suffering from lowered wages and increased mechanization – had shown Palmer that the misty-eyed ruralism of his youth was a lie. He had spent nearly all of the small legacy he had been living on, and now had a wife to support. Back in London he turned to painting more conventional landscapes, in tune with popular taste.