11,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

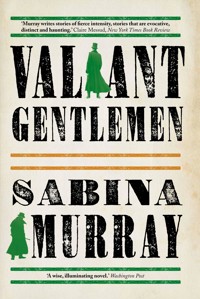

- Herausgeber: Grove Press UK

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

In prose that is darkly humorous and alive with detail, Valiant Gentlemen reimagines the lives and intimate friendships of humanitarian and Irish patriot Roger Casement; his closest friend, Herbert Ward; and Ward's extraordinary wife, the Argentinian-American heiress Sarita Sanford. Valiant Gentlemen takes the reader on an intimate journey, from Ward and Casement's misadventurous youth in the Congo - where, among other things, they bore witness to an Irish whiskey heir's taste for cannibalism - to Ward's marriage to Sarita and their flourishing family life in France, to Casement's covert homosexuality and enduring nomadic lifestyle floating between his work across the African continent and involvement in Irish politics. When World War I breaks out, Casement and Ward's longstanding political differences finally come to a head and when Ward and his teenage sons leave to fight on the frontlines for England, Casement begins to work alongside the Germans to help free Ireland from British rule. What results is tragic and riveting, as both men are forced to confront notions of love and betrayal in the face of the vastly different tracks their lives have taken.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2017

Ähnliche

For Esmond

CONTENTS

Title Page

Dedication

Part One

I. Matadi

II. The Florida

III. Yambuya

IV. Along the Congo

V. The Saale

VI. The United States

VII. Lecture Circuit

VIII. Sark

Part Two

I. The Congo

II. England

III. London

IV. Paris

V. Niger Protectorate

VI. Goring on Thames

VII. London

VIII. Cape Town

IX. Paris

X. The Anversille

XI. London

XII. The Pennsylvania

XIII. Ireland

XIV. Paris

XV. Rolleboise

XVI. The Putumayo

Part Three

I. Paris

II. London

III. New York

IV. Rolleboise

V. Christiania

VI. London

VII. Limburg

VIII. Rolleboise

IX. Berlin

X. The Vosges

XI. Banna Strand

XII. Paris

XIII. London

XIV. Paris

Acknowledgments

PART ONE

I

Matadi

September 1886

The first time Casement sees him, Ward is turned away, working on a sketch. He’s in a white shirt and the sleeves are rolled to the elbows, showing strong forearms darkened with exposure to the sun. The stance is perfect contrapposto, the hips angled, the right foot casually set forward. As if sensing Casement’s gaze, Ward turns and smiles. It is a romantic image that Casement has played over in his mind: first, the sight of the shoulders, the sun hitting the fair hair, the subtle movement of the arms, the hands, Ward’s attention drawn to some compelling subject.

“That’s ridiculous,” says Ward. “The first time we met was in an office. I was waiting for you to show up so that we could share the transport to Vivi. We shook hands. In fact, I think I saw you before you saw me.”

“How can you be so sure?”

“Well, for one thing, I wouldn’t be standing in the sun without my hat.”

“I remember the absence of the hat because it was exceptional.”

“Also,” adds Ward, “you can’t see my forearms from behind, not if I’m sketching. My left hand is holding the book and I’ve got the pen in my right. From where you were standing”—Ward presents his back to illustrate—“my arms are completely blocked by my torso. If you were an artist, you would know this.” Ward turns again to Casement and shakes his head. He’s wondering why Casement would find the need to create such a scenario. “That’s the problem with you, Casement. You’re a romantic, always making things up.”

“One of many, I’m sure.”

Casement grabs Ward’s sketchbook and flips through to an illustration of a mad bull elephant with a flailing native raised high in the beast’s trunk: Elephant and native lock eyes. Casement holds the illustration to Ward as evidence.

“Might happen. An elephant could get a native like this, and this is what it would look like,” says Ward. “But bodies don’t lie. You could never see my forearms from behind if I were sketching.”

Casement and Ward are company men, once employees of the International Association of the Congo, now members of the Sanford Exploring Expedition. Both are relieved to no longer be employed by King Leopold of Belgium, but the complications of working for England in this Congo Free State—a plot marked out as one might a flower bed—now under Belgian rule, are many. Casement and Ward have both run stores, but transportation is where skilled people are really needed. On the lower Congo, there are no roads, no rails nor navigable waterways that can accommodate more than a dugout canoe. Therefore, the only method of bringing things in (brass rods, cloth) and things out (ivory, rubber) is to engage porters. And one needs a lot of porters.

For sure, there are some Zanzibaris, people who showed up with the explorer Henry Morton Stanley and couldn’t find their way home, but the majority must be gathered from the local villages. And none of them are eager to leave their homes, wives, children, and fields. Also, the regulation load is an impressive sixty-five pounds. This the porters carry into the unfamiliar interior, where there are all manner of snakes and enemies, tribesmen who would rather eat you than call you brother.

“Looks like rain,” says Ward. Casement looks up at the sky. It does look like rain. “Actually it looks like deluge. Can one say that?”

“Ward, you can say whatever you want. This is Africa.”

Ward has engaged a young boy to carry some of his things and to gather firewood and cook. The boy is carrying sketchbooks and pens, also Ward’s razor, shaving brush, needle and thread, and extra cartridges, though Ward carries his own rifle and it is loaded.

Casement travels with his dog that he has named Tom, after a dog back in Ballycastle, who was probably named after a person.

In Kikongo, Casement asks the boy, “What is your name?”

“You know me, Mayala Swami,” says the boy, using Casement’s nickname. “I am Mbatchi, son to Luemba.”

“Yes,” says Casement, “now I can see it.”

Usually it is Casement traveling alone, or Ward traveling alone, the other white man needed to stay in camp, a civilizing presence in the village as on a map a pushpin signifies rule. But with the shipment of the Florida—a paddle steamer—has come a hoard of Belgians and Englishmen, so Casement and Ward can travel together and as twice the normal number of porters is going to be needed to bear the Florida’s tons of metal to the edge of Stanley Pool, perhaps twice the normal number of porter procurers is justified. Casement wonders how many porters are left in the Bakongo villages in the immediate surroundings. How far will he and Ward have to go to meet the quota?

Down the gentle slope he sees his camp demarcated in thatched fencing, a square ensnaring the regular shapes of huts, a large barracks, white men in white clothing, black men in black skin. He thinks his heart is ensnared—fenced in like that, and dismisses the thought. There might be poetry in that, but none he’ll write.

“Come on, Casement,” says Ward. “I’d like to get ahead of that rain.”

It is a narrow path, single file, and breaks into a wall of greenery. Down that path the birds call to each other in undecipherable phrasing. The air is heavy with moisture. Down that path exists an eternity of savages and savage custom. Behind him the sun beats down on the present. Ward picks up the pace and soon will no doubt start whistling something, an absurd folk song that he learned in Australia or, more likely, some shearing ballad from his time in New Zealand. He’ll break into song. Ward loves to sing, although Casement has the better voice.

“You’re dawdling,” says Ward.

“What’s the hurry?”

“Oh, I don’t know.” Ward is hoping for some hunting.

The rain, miraculously, holds off. The dog sniffs with focus, halts, then plunges off the path and into the jungle. There is a fierce rustling, then silence. One hopes poor Tom won’t be gutted by a boar. Little Mbatchi looks around for an explanation.

“Think he’s coming back?” says Ward.

“Of course,” says Casement.

“What’s the word for ‘dog’ in Kikongo?” asks Ward.

“You are going to make a joke.”

“Is it mbwa?”

“That’s Swahili.”

“I’ll think of it,” says Ward.

And he will. Ward is certainly proficient in the Kikongo of the lower Congo, and the Kibangi of the upper Congo. He is learning Swahili and has some knowledge of Kibabatu. Ward is proficient in turning one word into another. His vocabulary is enormous, but the words do not always add up. Ward manages to spin sentence after sentence without ever really speaking the language.

First the dog returns and then a dense rain moves over them. Mbatchi slips in the mud and is very nervous that something in his bag has broken, but on inspection, all is still intact and he smiles and his smile is radiant, and then there’s lunch: yam, mandioca, dried fish. That’s the eight hours done with and now they should be close to the village. Casement likes this walking—it reminds him of his early years in Ballycastle where there was little to do but walk. It was a childhood split between the lush green of the Antrim countryside and the rattling commerce of his cousins in Liverpool. Then, he had thought Liverpool and Ballycastle opposites, but here, in the Congo, this feels like an opposite.

“Ward,” says Casement. “Can there be three opposites?”

Ward responds with a dramatic sigh. He stands, shaking his head.

“Ward,” says Casement, coming to stand beside him. He was going to ask what was wrong, but now he sees. The Bakongo village has been deserted. A goat reveals itself from the far side of a hut. Ward is down on one knee studying the ground. He picks something up.

“Casings,” says Ward.

“Arab?”

“It would seem.”

“Well,” says Casement. “Let’s hope our friends got away.”

Just two weeks ago there had been a decent field of sorghum, but someone has harvested it all and the rich empty dirt looks like a fresh grave plot. Arab slavers normally stayed north of the river, but the Belgians too need labor and ultimately the difference between the Belgians and the Arabs is a matter of brass rods and the possibility of returning home. Better that Casement hires these natives for the English, who will at least pay them for their labor and treat them well, and with kindness, as these dark cousins ought to be treated. Mbatchi has found rope to tie up the goat and is leading it around.

“Mayala Swami, can I keep it?”

“It’s yours,” says Casement.

“That could have fed us,” says Ward.

“Carrying meat through the jungle has never been a favorite activity of mine,” says Casement. This is a reference to leopards.

“Even alive,” Ward counters, “it’s still meat.”

Mbatchi is tying the goat to a tree and the goat seems relieved of the burden of freedom.

“I’ve never understood why they call you that,” says Ward.

“What? Mayala Swami?”

“Doesn’t that mean ‘ladies’ man’?”

“Yes. That’s a reasonably close translation to the Kikongo.”

“But you aren’t a ladies’ man, Casement. As far as I know, you’re a perfect gentleman.” There’s the edge of disdain in Ward’s voice.

Casement smiles, looking at the ground. “How would you, Mayala Mbemba, understand?” Mayala Mbemba is Ward’s nickname. It means “wings of an eagle” and refers to the fact that Ward managed to walk forty miles in one day. Ward is very proud of this nickname and calls attention to it and explains it to anyone who will hear him.

“Do I detect envy, Casement?”

“Without doubt.” Casement fixes his gaze to the left and then the right. “We should eat.”

Mbatchi has collected a good pile of firewood. Because of the rain, it will not burn easily, but should get them through the night. Mbatchi is terrified of leopards and as one rather large print revealed itself at the edge of the stream when he was collecting water, his concern is justified.

“I’d love to bag a leopard,” says Ward.

“It wouldn’t be the first time,” says Casement. “And we’re not here to hunt. We’re already a day behind and who knows where else the Arabs have been.”

Ward is cleaning his gun. Casement brings out a bottle and takes a swig. He hands it to Ward.

“I don’t suppose that’s whiskey,” says Ward.

“Better. Malafu.” Palm wine goes down rough but does the work. A few mouthfuls of this and one sleeps through the night, no matter how many mosquitoes are biting.

Night falls with an almost audible thump. The frogs, tensed for action, begin their croaking and bellows, and giant moths—who also have been waiting for this moment—palm the air with their wings. Ward and Casement chose this shimbek to sleep in because of the rough Hessian curtains, made from sacks, covering the windows, and the old sheet draped across the door. Still, there is the constant rattle of insects worrying at the sheet to get in and—Casement suspects—to get out. But he is used to it. He remembers Taunt, the Chief Agent, saying just that morning—the wage ledger open in front of him, the inked numbers winking seductively—that this was not the life for an older man. Actually, what he’d said was, “It’s all right for you young men, walking about from village to village, camping beneath the stars, but for a man my age . . .” He of course was giving a bucolic wash to the actual work ahead since the “young men” made a tenth of what the likes of him made for sitting in one office or another and making order after order that was executed at far distance from the place of issue, and often to ill effect.

Casement is twenty-two, but feels significantly older. And then as he settles into this older way of being, feels suddenly and impossibly young with no direction and no purpose.

“Ward, are you still awake?” he asks the dark. “Ward?”

“Now,” Ward replies thickly, “awoken.”

“We’ll need a tent and not just any tent. I want a big officer’s tent. And no more of this malafu. I want a case of Madeira and a porter to carry it.”

“What are you talking about?”

“When they finally have the Florida in pieces and we’re doing the portage.”

“Why now?” asks Ward. “Why all of a sudden do you want to travel like a gentleman?”

“You can be a gentleman and no one treats you well. But I think if we demand a case of Madeira and a servant or two, then we might be able to negotiate a better rate.”

“That’s ridiculous,” says Ward, rolling over, “and absolutely brilliant.”

The Florida is a paddle steamer imported for the purpose of getting goods from Leopoldville on the southern edge of Stanley Pool across to the northern bank, and, more importantly, of bringing goods—ivory and rubber—back. Nothing larger than a dugout can make it up the Congo, and then, not even the whole distance. The mighty Congo in no way resembles any of the rivers of Casement’s youth. There are waterfalls and cataracts and currents that would make the most scientific mind conceive of long-fingered sorcerers plucking unlucky souls from the surface and dragging them beneath. There is a bubbling quality to the cataracts; one named “Hell’s Cauldron” is just downriver from Matadi. More than once Casement has seen a native, arms raised up, mouth shouting, voice obliterated by the crush of water, spin round and round and disappear as if there were an enormous drain at work. The upper part of the Congo, from Stanley Pool to the east, is navigable and there are two or three boats—missionaries—chugging industriously, perhaps transporting souls back and forth across the pool, in some sort of God-pleasing transaction.

The only way to get the Florida to the shore of Stanley Pool is by porter and the only way this can be accomplished is in pieces—many pieces. At present no better way exists, and—in fact—no other way. There is talk of a railway from Boma to Leopoldville, which would tear up the country but most likely have a civilizing influence. Maybe that would be fine, but the work involved (would he sign on for that?) gives one pause. And Casement’s grown tired of dealing with caravans, and porters who are ambushed and injured and often run off with their loads into the jungle where it’s impossible to find them, as if the jungle folds her own in her arms to protect them.

Two weeks have passed since Ward and Casement assembled the caravan and they are back in Matadi, making final arrangements. All in all, Casement’s pleased with what they’ve managed—many Bakongo, who are an honest people and hard-working and with whom, since he’s known to them and speaks the language well, he shares an easy relationship. The rest are mostly well-traveled Loango, who are therefore skilled at distinguishing friendly chiefs from hostile chiefs. But the territory from Matadi along the Congo to Leopoldville has all been opened up anyway and Casement has no reason to predict hostility from the many chiefs he will encounter. Some villages have no more than twenty inhabitants, and some upward of 300, and all a chief and witch doctor to keep things lively.

Many of the pieces of the Florida cannot be broken down to the regulation sixty-five pounds and will have to be carried in hammocks strung between bamboo poles, the weight shared by two porters. The shaft of the Florida is nearly a ton and cannot be taken apart and so will have to be transported by cart. Some higher-up has remembered the cart, although neglected to provide anything with which to pull it. Ward left earlier in the morning to find bullocks and has already taken an hour longer than Casement thought he would. Casement exhales into the heat. A child, whom he knows by sight, comes up to him.

“Mayala Swami, do you have a gift for me?”

Matabicho is the word the child uses, which culturally is somewhere between a gift and a bribe.

“I might,” he replies in Kikongo, “if you can tell me where Mayala Mbemba is.”

“By the river looking at the Dutch trader’s women.”

Casement gives the child a piece of hardtack, which was in his pocket when he put on his trousers this morning. When did he put it there? The child seems happy and Casement is satisfied because he knows, from experience, that the child’s information is correct.

There is Ward standing on the riverbank watching the spectacle of De Groot’s harem—four women, their glossy skin set off by yards of embroidered snow-white muslin, arrange themselves into a canoe amid a musical chatter.

Casement sees his shadow standing next to Ward’s, but is still.

“I know you’re there, Casement,” says Ward. “And I can feel your disapproval.”

“Of the Dutch trader?”

“Of me.”

“Four is a lot of women,” says Casement.

“One would be enough.”

“It’s easily arranged.”

“And a lot of money. It wouldn’t be worth it with the work we’re doing.”

“Not unless she could walk forty miles in one day.”

“Very funny,” says Ward. He turns from the spectacle of the women with some effort.

“Did you get the bullocks?” Casement asks.

“It has been decided that we should have no bullocks,” a little humor here, “as they are highly susceptible to the tse-tse. So instead it has been proposed that the enormity of the shaft,” more humor, “be offset with a significant number of porters.”

“Porters?”

Ward nods.

“I would recommend at least a hundred men,” says Casement. “One hundred, no fewer.”

“Which is what I recommended and that number is on their way up from Vivi.”

“How?”

“The Arab Tippo Tib is supplying the porters.”

“Tippo Tib is a slave trader,” says Casement. “Are we now in business with him?”

“Someone is,” replies Ward.

There’s a moment where both Casement and Ward contemplate their insignificance. We are pawns, they think together. We are powerless. Then the moment passes, carried off by a doctoring wind.

“Did you get the Madeira?” asks Ward.

Casement nods. It would seem they are provisioned.

II

The Florida

March 1887

Today there might be rain. Ward looks upriver, at the sandbars rising like the vertebrae of some giant creature. Navigation on these stretches will always be dicey. A group of four birds flies speedily up the river and Ward follows them with his hands grasped around an imaginary rifle, as if he’s setting up a shot. Mbatchi disturbs his reverie by pulling on his pants leg.

“What?” says Ward. “Does someone need me?”

Mbatchi nods.

The messenger speaks Kikongo, although he’s Kibabatu, from upriver. He tells Ward about a village just over the ridge that has food to trade—sorghum for the porters, maybe some goat stew for him and Casement—which is good news because two years ago and not far from their present location a French missionary was taken out by a spear, although the flinger of the spear was never seen: as if the jungle herself had flung it unaided by human hands. According to this messenger, there is no need for concern: All here is peaceful. Perhaps there will be something of interest for Ward to sketch. He shows the messenger a few pages from his sketchbook and the messenger is very impressed and smiles warmly. The next village has beautiful women, says the messenger. Ward explains that his art is not confined to what is beautiful. The messenger says that that is good because the men of this village (a head shake here) are very ugly. Ward gets the joke and laughs very loud—too loud, because he is so pleased with himself for understanding humor in Kikongo. He and the messenger laugh together. Next, Ward asks about elephants.

After Ward has arranged a meal for the messenger, he goes to look for Casement, who is redistributing the contents of one of the baskets as the man who was carrying it has gone lame. Casement is looking at the man’s foot where a thorn has become imbedded. The foot is inflamed.

“Shoes would solve some of this,” says Casement.

“We would need a lot of porters to bring shoes to this many porters.”

“And those porters would also need shoes.” Casement smiles. He tells the man, one of the Loango, that he is welcome to go home now. He will be paid for his labor and should take care with his foot so that it heals now rather than becomes more infected.

“We’re not supposed to give partial payments,” says Ward. “The job is the whole portage, not just two weeks.”

“It’s only a few brass rods,” says Casement.

“I’m not arguing with you,” says Ward. “But we’re about to have a rash of people stepping on thorns. And I think we’re up to ten people who have run off. The porters are supposed to be chained.”

“And then when one falls, we risk injuring the entire column.”

“Which is why we’re doing it your way. But I’m not sure if it’s the right way.”

Casement pretends to consider. He shrugs. He looks up at Ward. “I heard there was a messenger.”

“From Stanley Pool.”

“What did he say?”

“He said there was a lone bull elephant maybe four miles from here. He didn’t get a good look at the tusks, but surely resting the men for a couple of hours would be good for all.”

“And surely they didn’t send a messenger from Stanley Pool to tell you that.”

“No,” says Ward. “Troup wanted to know if we have the brass wire for the boiler assembly.”

“I’m not sure,” says Casement.

“I already checked and the wire’s missing. It was supposed to arrive at Stanley Pool with a bunch of Manyema porters supplied by Tippo Tib,” says Ward. “Tippo Tib insists that it’s either on its way, or has arrived and been misplaced, or that maybe the Manyema porters got mixed in with ours.”

“I think we would have noticed that.”

“That’s what I said.”

“Anything else?”

“There’s a village less than a half day’s march from here.” Ward shifts his weight. “Can I go after that elephant?”

Casement thinks. “If you bag it, that’s meat for the men, and they could use something better than manioc. What if you go with Mbatchi and eight men to carry the meat in case you’re lucky, and I’ll pitch camp in another five or so miles, which should bring us closer to the village, and you can meet us there.”

“You could wait for me here.”

“Mayala Mbemba,” says Casement, “what’s another five miles to you—you, who walked forty miles in one day?”

They finally find the elephant after trekking close to six miles. One of Ward’s men, Mboko, an exceptionally tall fellow at six feet four, sights it at good range. Ward, who is on the short side, something that served him well when he was an acrobat in Sydney, can barely see over the top of the long grass. But he’s good at balancing.

What he would really like to say is: Mboko, would you mind terribly if I got up on your shoulders? Instead, he says: “Mboko, I sit on back.” And mimes shooting with his rifle.

Mboko nods in response. Ward clambers onto Mboko’s back and then onto his shoulders and another man hands him back his rifle. There’s the elephant feeding, stripping the bark from a young tree. The elephant is flapping its ears, swinging its tail peacefully. Mboko, aware of the shifting breeze, moves to right and left, anxious to stay downwind. A lone bull elephant is very dangerous and even if all seems quiet—bucolic—Ward knows that if the elephant picks up their scent, it will attack. He nudges Mboko with his heel and Mboko edges forward through the grass.

Ward has a straight shot to the back of the beast’s head. Not the most exciting way to kill an elephant, he thinks. If he gets this shot, he won’t be charged, and the brute will most likely die instantly. If he gets this shot, he won’t have to track the elephant through the jungle for a day and a night—he’s done that before—and there won’t be much of a story. If he gets this shot, he’ll walk over to see what sort of tusks there are, rather than seeing the tusks come at him. And he’s witnessed people who have been gored by elephants, although he’s never actually seen someone in the process of being gored.

He feels Mboko tense up beneath him. They’re close now and Mboko is wondering why he doesn’t take the shot. And then the rifle is raised. Ward holds steady and sights, finger exerting an even pressure on the trigger, squeezing calmly. BLAM. A perfect hit to the back of the head. The elephant shudders. Reload. BLAM. And the elephant falls. After one more shot for certain death, they cut the thing up and cart what can be carted back to camp.

Casement is fiddling with some verse. Yes, fiddling. He looks at the lines:

The barren hills of Ulster held a race proscribed and banned

Who from their lofty refuge viewed their own so fertile land

It’s a bit stiff, but the meter’s right. He thinks of Ward’s drawings, all Africans, and his poems, all Irish history. Is this what makes them different, that Ward constructs himself out of his own personal history, while Casement’s personality demands a further reach? Why write about post-Plantation Ulster in the Congo? Well, the Bakongos are somewhat displaced as they shuttle around carrying things for the English. And he is somewhat displaced, first as one who is Irish when he’s not being British, British when he’s not being Irish, and sometimes both simultaneously. He checks his watch. It is closing in on eight, although time means little here—only daylight and darkness. He hears a swell of expectant chatter. Ward must be back.

Sure enough, there’s Ward bearing his usual cheerful expression as if he’s just walked into a parlor for a Saturday chitchat, or bumped into Casement on the way to a cricket match. The porters’ baskets are full of meat.

“What’s for dinner?” says Ward.

“Looks like elephant,” Casement replies.

“I’m not eating elephant,” says Ward.

“It tastes just like hippo, and I know you eat that.”

“It does not taste like hippo, well, not much. And I only eat hippo if it’s very young.” Ward sits on a crate by Casement’s chair. “What have you got there?”

“Poem.”

“Any good?”

“Not yet.”

Ward flips open his sketchbook and finds the picture. “What do you think?”

“It’s an elephant.”

“That all?”

“It’s dead.”

“The perspective was very difficult. Look at the legs.”

“That is some accomplished foreshortening. Why’d you do it?”

“They were going to chop it up. It seemed a shame not to preserve it.”

“Then why’d you kill it?”

The tent has been erected, prepped for eating rather than sleeping, with the walls rolled up and buckled in place. There are chairs and a table and a cloth on the table and the Madeira is there, half full, a reminder that sometimes these young men are rewarded. A moth enters from the right side of the tent, inspiring a bat the size of a cat to dispose of it midway.

“Stanley’s book, Through the Dark Continent, have you read it?” Ward asks.

“Yes. Hasn’t everyone?”

“It’s full of bravado,” says Ward.

“I think that’s the typical writing style of short, ill-tempered men.”

“So you were not taken in by Stanley?”

“I think I was,” says Casement, and he tops up his glass, “which has contributed to my assessment of his writing style.”

Ward fixes Casement with an appallingly earnest look. “Casement, all we do is walk. First we walk tens of miles finding porters, then we march them back to Matadi or Vivi or Boma or wherever. Let’s say we do this in the pouring rain. Then we put things in baskets and the porters put the baskets on their heads, and then we walk some more. The rain clears up and it gets really hot. And then. Well. More walking.”

“What does this have to do with Stanley?”

“What made his experience spectacular and adventurous when ours seems so boring?”

Casement considers. “He was the first. He got shot at. He ran out of food.”

“We run out of food,” says Ward.

“And isn’t it exciting when that happens?”

“You’re making fun of me.” The insects crawling on the lamp are casting fantastic shadows on the inside of the tent.

“Yes.”

In the porters’ camp, some have started singing. More join in, the chorus of porters rising and falling as if carried back and forth by a fickle current.

“God,” says Ward, “you would think they could sing something better.”

“Are you homesick, Ward?” The porters’ singing grows louder and now there’s a drum in with it. Casement smiles. “Do you think we could teach them ‘Greensleeves’?”

Ward slams his glass down, tops it up, and drinks. “I hate England,” Ward responds, “and England hates me. But that doesn’t mean that I like the Congo Free State.”

“‘Alas, my love,’” starts Casement, “‘you do me wrong,’” his voice catching with the distant porters’, “‘to cast me off, discourteously.’” This is not a military drum. “‘For I have loved you—’” This is a heart beating.

“‘—well and long!’” sings Ward, who voices like a drunken publican even when sober.

And together, “‘delighting in your company.’”

After “Greensleeves” they sing “Jerusalem.” And after that, some interminably long Irish thing to which Casement knows all the words and now, after hearing the chorus once, Ward knows it, and he too wants the young lovers to “come to the bower,” although he has no idea what exactly that means, or ever meant.

The day enters with its usual blanket of heat. Casement might welcome rain, but that would transform the path into a river, which would, in turn, give way to a mud track. And the brief relief from the insect population that happens in the wake of these torrential downpours would only offer up the intense humidity that mosquitoes love so well. One discomfort is merely exchanged for another, which makes the absence of choice about such things almost tolerable. Or at least promotes a philosophical stance regarding his lack of control.

Ward is dissatisfied and restless. Before he agreed to this latest venture, Ward had been about to leave Africa for England and return home—even if he denied having one. He was ready to find a career for himself, although he seemed more focused on finding a woman. Ward is only involved in the transport of the Florida because the pay is very good. Ward is now making twenty pounds per year more than he himself is, but he can’t begrudge Ward anything. For his company alone, Casement would have paid the difference in their salaries. It is Ward who punctuates his days: Ward in the morning by the edge of the water in his breeches; Ward’s signature high-noon squint; Ward’s rangy walk as he patrols the length of the column, his constant interrogation of messengers and locals about the possibility of game; and late-afternoon Ward with his sketchbook, wandering in search of something to draw. Casement envies the basic appeal of drawing—one’s vision is, if nothing else, oversubscribed—whereas he, with his poems, is often faced with the blankness of his own mind that he struggles to populate with long-dead Irish kings.

Casement sees Ward chatting with one of the cook’s assistants. The corners of Ward’s mouth are pulled back in displeasure, while the hands of the cook’s assistant, fingers splayed and heels of palms supporting invisible riches, describe some gustatory delight.

Ward catches Casement staring and—for one long second—holds his gaze.

“Bush rat,” he shouts.

“Bush rat?”

“On the menu,” says Ward, coming over. “What did you think I meant?”

“I wasn’t thinking,” says Casement. “It isn’t rewarded, so why bother?”

Ward is flipping through his sketchbook. “What?” he says. This particular “what” means that Ward has missed what’s been said.

“Anything interesting today?” asks Casement.

“Just some Manyanga,” says Ward. He flips through his book, brushing bugs off as he goes, bugs that become pressed and preserved like the flowers pressed and preserved by women at home. There are sketches of plants, a porter with radiating facial scarring, a still life of gourds and pipes.

“Stop,” says Casement.

Together they look at a woman, full-lipped, erect carriage, hair shaved close to the head. “You like her?”

“Not the woman. The necklace.” It’s endearing, Ward’s ability to chronicle everything without actually seeing it. “Her necklace, Ward. Look at it.”

“It’s quite unusual.” The necklace is formed in a fine coil about the woman’s neck, like a loose spring.

“It’s wire.”

“Probably.”

“It’s brass wire.”

“Oh,” says Ward. “That’s right. The missing brass wire for the boiler assembly.”

Certainly this is funny, but the effort required to gather up the brass wire—or what is still collectable—will be significant. He’ll send out some men tonight, before the women and their wire disappear. Of course this was all predictable. Tippo Tib is corrupt as they come and if only the supervisors would acknowledge that there is a difference between a dissembling Arab slaver and, for example, an honest Bakongo chief, such mistakes would be rare. As it is, the Belgians, the English, the French would all rather do business with the Arabs because of their smattering of European language and their inclination to wear clothing.

“Here,” says Ward, pushing the sketchbook into Casement’s arms, “take a look. Maybe you’ll find something else.”

“Where are you going?” asks Casement.

“To go find something that’s not a bush rat.” Ward calls out to Mbatchi and then heads towards the greenery. And, waving, “See you at dinner.” Mbatchi, loaded down with rifle and bag full of shot, follows after him, the pale soles of his feet raising up, lifting a low cloud of dust as he runs to catch Ward.

Ward does not appear that evening, nor Mbatchi, and although Casement knows he should not worry, his sleep is troubled by thoughts of poisonous snakes and the heavy crush of jungle that precedes the leopard’s kill. And there are natives who can see the value of capturing a man like Ward, with his golden hair and straight shoulders. Casement opens his eyes expecting the darkness but it is now bright. He can hear the river rushing against rocks, tearing at the banks. He has managed to sleep. Tom is panting and smiling on the floor beside him. He sits up in his cot and hears a child’s voice—it’s Mbatchi—chattering away to someone, although the camp still holds the quiet of early morning. He hears, Englishman, and, many Arabs, and, like a goat only bigger with very long ears. Casement gets up from his cot and parts the canvas flap to leave his tent. He reminds himself that he is not Ward’s keeper. He will be cheerful, not scolding.

“Mbatchi!” he says, too jovially. “You’re back. What is this goat with long, long ears?”

“For the Arabs to sit on.”

“It’s a donkey,” says Casement. “Don-key.” It would be good for the boy to learn some English. He pats Mbatchi’s head. He smiles, straining to be relaxed. “And where’s Mayala Mbemba?”

“With the white man,” says Mbatchi. “There were so many people,” he gestures around him, “and the great English chief is there too, but I didn’t see him.”

“The great English chief,” says Casement.

“His name is donk-key.” Mbatchi shakes his head. “No, Stankey. His name is Stankey.”

“Stankey? Do you mean Stanley?”

“Yes!” says Mbatchi.

“And what is Stanley doing in this region?”

“He is going to save another man, another great man.”

What nonsense is this?

“Mayala Mbemba says to go on without him and that he will find us in the afternoon.”

“Ah,” says Casement. He is walking away when he changes his mind. “Mbatchi,” he says, “this white man that you say Mayala Mbemba was speaking with, he wasn’t Stanley?”

“No.”

“What did he look like?”

“Like you, like Mayala Swami. He is a white man.”

Which is, of course, the correct response. What is Casement looking for from Mbatchi, who sorts into either the familiar or the unfamiliar? To Mbatchi, this anonymous white man appears in the same alien register as a donkey or a crowd of Arabs. And what did he expect Mbatchi to say? That this other white man is tall and strong? That this other white man makes Mayala Mbemba laugh, or that they went hunting together? This is insanity and all diseases of the mind are easily succumbed to in Africa. One must be vigilant.

“Mayala Swami,” comes a voice.

“What?” says Casement, startled from his thoughts. It’s Kiskela, a Bakongo, and a supervisor.

Kiskela thinks before speaking. “We have gathered together the Manyanga women with the brass-wire jewelry, but they do not want to give it up. These are gifts, they say, from their husbands. We can take it from them, but they will be very angry, and the Manyanga are usually friends, but if we take jewelry from their women, they will not be so kind to us, and they have the fields just to the north. We will need to buy manioc from them—”

“I understand,” says Casement. He feels rescued by duty. What to do? “Take a case of brass rods and some cloth from the stores and buy the jewelry back. Bargain hard and keep track of everything. We’ll try to recoup some of our losses when we’re purchasing food.” Kiskela has a photographic memory for numbers and amounts. His retention of such knowledge is impressive, a gift that many of his people have—necessary when there is no system of writing.

“Is there something else?” asks Casement, as Kiskela has not moved.

“Mayala Swami, the women will want to see you.”

“Fine,” says Casement. “I will go there and wave my big white head at them.”

Kiskela smiles.

“I haven’t had any breakfast,” says Casement.

“You will have some soon,” says Kiskela.

Casement appreciates this about Kiskela, that he follows orders cleanly but always makes it seem as if getting things done is of personal satisfaction. There is respect here, and kindness, but not quite friendship.

This is a lonely, lonely place. Casement is twenty-two years old. In another life, he would be elbow-on-the-bar with other men his age, or reading history at Trinity.

“Kiskela!” he shouts. “No bush rat, please.”

* * *

What does Casement know of Henry Morton Stanley, the great explorer of Africa? He knows him as a charlatan. He’s heard the gossip—Stanley, a workhouse Welshman who escapes to America and reinvents himself as a Wild West journalist and now, suddenly, he’s the best expression of an intrepid Englishman. His first publicity stunt was finding Livingstone and delivering the droll phrase, “Livingstone, I presume.” Anyone who had actually met Stanley knew that he had no wit, even poor wit, and could not have come up with that. Stanley had carted this print-ready statement from London, along with his silly outfit and notoriously bad feet.

David Livingstone was a mediocre explorer, famous for confusing the source of the Nile with the Lualaba River, which flows into Upper Congo Lake. He also had a missionary bent, or a savior complex, depending on whom you spoke to. The fact of his ever being lost is up for debate. Ultimately, Livingstone became so confused with malarial visions that he ceased all communication with the civilized world—and was presumed dead—for six years. That is, until Stanley paid a visit to him, where he was living on the shores of Lake Tanganyika, the whole venture funded by the New York Herald. The jury is still out as to whether Livingstone wanted to be saved, or found, or conversed with, or whatever it was that Stanley had actually done. Still, it was a good news story. And how to follow it up?

Apparently with this stunt of saving Emin Pasha. The whole thing is absurd and no doubt the copy was already typeset before Stanley left for Africa—more of a script just waiting for Stanley to act it out.

Casement and Ward are facing off across the dinner table but Ward, his legs extended and ankles crossed, seems more occupied with his boots, which could use a polish.

“You’re not making any sense,” says Casement. He hears the edge in his voice, is worried that he sounds womanly.

“Well, you’re not making much of an effort to figure out the facts, are you?” Ward responds.

Ward is determined to attach himself to Stanley, since he fancies himself an adventurer. “I’m not the one who has been taken in by this ridiculous enterprise. In your effort to make the facts clear to me, it’s obvious that you have no idea what Stanley is up to.”

Casement reminds himself to sound less spurned, more like a counselor. “You must admit, there’s something odd about the venture.”

“Casement, I don’t understand why you’re so against Stanley.”

“I’m against all this puffery.” Casement shakes his head. “Who is this man?”

“The name is Ingham and he’s a representative of the Emin Pasha Relief Expedition.”

The clarity of this statement hangs in the air. Casement smoothes his mustaches. “And you said he was very interested in the Florida.”

“Yes. And in me. He seems to think I could be very useful to Stanley.”

“When we have the Florida at the edge of the Pool, it will be the only steamboat available for purely trade purposes.” Casement says the Pool instead of Stanley Pool because he refuses to be complicit in a testament to Stanley. “Every other boat is in the service of God and in the hands of the missionaries. He wants the Florida. He means to commandeer it.”

“Really?” says Ward. “And what if he does?” Ward empties the last of the bottle into his glass.

And so what? Casement will get nowhere with bullying. If anything he’ll prove himself to be bad company, and then it’s all over. “All right, Ward. So who is this Emin Pasha? What sort of man is he, and what has put him in such a perilous position?”

“Well, he’s a good sort of fellow.”

“He is?”

“He’s a consul, or a governor. And he’s an ally.”

Casement nods, affecting patience as Ward tries to put it all together. He feels like a schoolmaster watching as a student flubs the lesson. “And where is he?”

“He’s in Equatoria, southern Sudan.”

“Equatoria,” Casement considers. It’s beginning to make more sense. “He’s one of Gordon’s provincial governors, isn’t he?”

General Gordon, Governor General of Sudan, had been slaughtered by Mahdist revolutionaries a year earlier. At first, the English hadn’t wanted to get involved, and when they finally came around to seeing that perhaps Gordon did indeed deserve some help, it was too late. Troops arrived two days after the fall of Khartoum and Gordon’s death. Many British subjects had lost their lives and images of hanky-clutching women being carried off by turbaned men on Arab steeds had sold a lot of newspapers.

“If Emin Pasha is in Sudan, why is Stanley here in the Belgian Congo?”

“I wondered the same thing.” Ward seems proud of knowing to ask this obvious question. “It seems that old King Leopold also wants to give a hand in saving Emin Pasha, and so Stanley is starting here, you know, getting porters and supplies, the usual.”

“That’s ridiculous. To get to Equatoria with as many men as seems is happening, one should go from Dar el Salaam. Perhaps Equatoria looks close on a map, but that region is almost completely unknown and what’s known about it is not good. The Ituri Forest is notoriously populated with cannibal tribes and much of it’s a swamp.”

“It sounds like an adventure.”

“No, it sounds like money. Leopold. He wants to know if there’s something in that territory worth claiming—rubber, ivory. He’s thinks that sending Stanley through the jungle to rescue this Emin Pasha with the support of England, under the English flag—”

“It’s not, actually,” says Ward. “It’s not the English flag. They’re marching forward under the flag of the New York Yacht Club.”

“So there’s American money too.”

“Casement,” says Ward. “You can be so cynical. And, frankly, you sound like an old man. All we have, you and I, is the fact that we’re young and strong. We don’t have families to worry about, well, not yet, and we can do anything we want, without hurting anyone but ourselves.”

This sounds like Ward, but a little more like some unseen person filtered through Ward’s idiom. Casement is tempted to ask Ward if he’s thinking of joining this absurd Emin Pasha Relief Expedition, but he’s worried that by asking such a question, he’ll be validating the possibility. In his bones, buried far from thought, he already knows that Ward is gone. Casement realizes that he’s rolling the empty bottle in his hands.

“Is that it for the bottle?” Ward asks.

“Yes.”

“Don’t you think we should call for another?”

They have left the riverbank to cut a shorter distance between two of the Congo’s coils. The terrain here is flatter with long grass, grass that hisses when the breeze stirs. Birds are occasionally flushed from its pile and take to the air, their wings singing. A herd of deer the size of dogs had been sighted, but by the time the rifle was raised, Ward running up the column of men, eager to get a shot, they were gone. Casement had watched the deer escape. Leaping from the grass made them seem like fish breaking the surface of the water.

The cart carrying the shaft for the Florida, pulled by a hundred men, has presented more problems than even Casement, who has a gift for seeing potential disaster, could have predicted. The bed is low-slung, the wheels thick and wooden, a most primitive machine that it is hard to imagine any civilized people using unless one goes far, far back. And this track through the jungle—packed dirt when dry and when it rains a river of mud—is made for porters. This awkward, deformed vehicle requires something of a road. When a curve is encountered, a new path must be struck and the men must strike it. Casement knows something of surveying and with each passing day knows something more. How many times has he heard, “Mayala Swami, the wheel is off. What do we do?” And how many times has he responded, “When that happens, we put the wheel back.” Which is accomplished as the insects swarm and the heat bakes down and the pause in progress reminds all the porters who have considered deserting that this might be their only chance, who set down their bundles carefully and take off at a good clip. But what to do now?

He hears the men calling out first and then Tom’s barking. The hillock is low and although now Casement sees he should have been supervising, he was reviewing food purchases to be made that evening with Kiskela. He would like to blame this on Ward, but Casement had asked Ward to check the rear of the column since they were approaching the village and the temptation to run off was strong.

Ward comes up beside Casement as they view the disaster. Apparently, as the cart had begun to roll down the hill, the men behind had not been able to slow it. There were so many men pulling the thing that those in front were under the impression that the cart was once again on level ground, which is why they’d resumed their efforts. The cart had sped along briefly—a slow but unstoppable runaway—until it had managed to become beached upon a low boulder, breaking its axle in the process.

“Is anyone hurt?” asks Ward.

“One of the porters tripped on a root while trying to get out of the way and split his lip.” Sure enough, there is the porter gingerly touching his swollen mouth, testing his teeth carefully against the wound as if to confirm that his own teeth are indeed responsible for the injury.

“Well, we should be grateful,” says Ward cautiously, sensing Casement’s mood.

“Oh, I am,” says Casement. “I am as grateful as they come. Do you hear this?” He shouts at a deaf god, “This is gratitude!”

“Can we make—”

“No. Even if we find ironwood out here, we don’t have the tools to fell it. And anything else will just snap immediately.” Casement has lost. The cart has given Ward the excuse to leave him and Casement savors his defeat. “We’ll need to purchase another axle.”

“Well then,” says Ward, “one of us needs to go to Matadi.”

Casement nods. “True.”

“Did you want to go?” Ward asks, forcedly casual.

If Casement goes, the entire operation will fall apart. Someone will see a fresh leopard print and Ward will go after it, the men will desert, and those who don’t will be faced with meager rations as Ward will have forgotten to purchase supplies. “Me? Rather than you, Wings of an Eagle, and your forty miles in one day?”

“All right,” says Ward. He looks around, twitchingly, for some reason to stay to present itself.

Casement presents a wan smile.

“Oh well. I should probably get going, you know, while there’s light.”

“That would seem to be what’s called for.” So that’s that then. “I’ll push on and leave a rear patrol with the cart.” Casement is suddenly exhausted.

Mbatchi shows himself. The clever boy has been picking up some English. “Mayala Mbemba, are we going to Matadi?”

“You stay, Mbatchi,” says Ward. “Too far for you, for little legs.” He rubs Mbatchi’s head affectionately and Mbatchi looks up at Casement. Casement, swallowing, looks back and his look says, Yes, clever boy, we’ve both been abandoned.

Sleep does not come for Casement. He pictures Ward making the trip back to Matadi, his long strides, his sweeping the track for prints, the hearty calling-out to the natives he encounters with his fumbling Bakongo and Swahili. Stanley is in Matadi putting together what he insists is the greatest rescue ever mounted. Stanley will push through the jungle, through hostile tribes, through unforgiving terrain, where Emin Pasha, surrounded by blood-thirsty Moslems, is sure to perish until Stanley—cue the bugle—sweeps down vanquishing the heathen: a cliché that would only appeal to Ward, who seems more of an adolescent than a man, although this is perhaps the source of his appeal. Casement’s love for his friend, well, maybe it’s better that Ward should leave before Casement has to acknowledge that it’s something else. He stifles a low sob and instantly loathes himself. He thinks of writing a few lines, but, knowing that they will be awful, does not pick up the pen. A moment of painful consciousness, where he senses every corner of self flung out across the universe—exposed, without skin—ticks by. He wonders if the shot in his pouch has stayed dry. Sensing distress, Tom pants by the edge of the cot. Casement pats the dog, momentarily comforted. They stay like this a moment, but then Tom’s head pivots quickly and he emits a low growl.

“Is there someone there?” Casement asks of the dark.

“Mayala Swami, it’s only me.”

“It’s all right, Tom,” Casement tells the dog. “Come in, Mbatchi.”

Mbatchi steps inside. He’s holding his bedroll.

“It’s very late, Mbatchi. Why aren’t you asleep?”

“Did I wake you up?”

“No, no.”

“You couldn’t sleep,” says Mbatchi, “because Mayala Mbemba is going to Matadi. You think he isn’t coming back because he wants to go with Stanley to save the other great man.”

“How do you know this?”

Mbatchi thinks but doesn’t answer. He too has had a feeling that has become a certainty.

“You should sleep, Mbatchi.”

Casement watches him, but the boy does not move. He stands with his bedroll looking down at the ground.

“Did you sleep in Mayala Mbemba’s tent?”

Mbatchi nods.

“I thought you slept in the cook’s tent.”

“I didn’t like the smoke.”

“Did you want to sleep here?”

Mbatchi clearly does, but he casts a nervous look over at Tom.

“Tom’s all right. Come here, pat his head. He likes it when you scratch behind his ears.”

Mbatchi comes over nervously but scratches the dog’s head. The dog smiles.

“You can set up your bed in the corner,” says Casement. “And Tom will make sure that no snakes come in.” Casement raises his eyebrows. “You’ll be very safe with Tom around.”

Mbatchi takes his bedroll over to the corner and lays it out.

“Go to sleep now, good night.”

Mbatchi is lying down but still not ready for sleep. “Mayala Swami, what will I do now?”

“Well, I can send you back to your parents with the next messenger. I’m sure you miss them.”

Silence stands briefly as the boy thinks. “Can I work for you?” There’s a nervous sadness in the voice, as if he fears that he’s not wanted.

More silence. What is best? “All right,” says Casement, “you can carry my surveying tools, but most important of all, you must make sure that Tom has water. He needs to drink several times a day, and I do forget. You will be very useful.”

“Good,” says Mbatchi. Casement hears the boy roll over and almost instantly a whistling snore can be heard from the corner of the tent.

Well, that’s settled, thinks Casement. He’ll take care of Mbatchi, make sure he is well fed and in good health, that he is always happy and feels safe, that he rests when he needs to and is protected from those that might harm him. And he’ll work and perform all the tasks required of him, one after the other, until his life is wasted or there’s nothing left to do.

III

Yambuya

June 1887

The camp hovers on the side of a river and is enclosed by a fence of sticks that—when observed all at once—resemble nothing more than the teeth of a comb. There are several huts made of tree limbs, planks, scrap metal, whatever was available during construction, and these are thatched with grass. Three months have passed since Ward signed on for the venture, and he has yet to do anything beyond presenting himself in various locations to little purpose. And now he is presenting himself here. Stanley and half the officers and the available porters have already left, their drums but a distant memory. Stanley is in a hurry to rescue Emin Pasha while he still needs rescuing, before the situation resolves itself.

Ward has been made a fool and he knows it. He and four other officers—Stanley’s less desirables—are to wait in Yambuya until they have sufficient porters to join the expedition. They are to guard the supplies deemed unnecessary at this juncture. A Major Barttelot is the top-ranking officer. Ward explains that he has experience with porters, that he speaks local languages and is a good shot. Barttelot finds none of this interesting. Barttelot doesn’t want to look Ward in the eye but rather keeps swiveling—as Ward moves to face him—so that Ward remains sighted over his left shoulder. Ward asks, “Where ought I put my things?”

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!